Abstract

In recent years, domestic and international air passenger markets have expanded steadily around the world with the rapid growth of low cost carriers and aggressive route expansion; however, the unprecedented crisis caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in greatly decreased air travel and an uncertain future for the aviation industry. The present study examined South Korean passengers, airlines, and government policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it suggests policy directions for the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. Air passengers respond to internal and external factors, and their demand for travel will increase with the reduction in global COVID cases and vaccine distribution. South Korean airlines have used various means to overcome decreased passenger numbers, such as domestic route transitions, freight transportation expansion, and mergers and acquisitions; Korean Air recorded a profit through its foray into cargo transport in 2020. The Korean government is trying to curb the spread of COVID-19 and help the industry to recover by establishing an airport quarantine system at Incheon international airport. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, it is necessary to continuously monitor the responses of passengers, industry, and governments and to share relevant information.

Keywords: COVID-19, Air passenger demand, South Korean airlines, Strategic response, Airport quarantine

1. Introduction

Domestic and international air passenger markets have seen an increase with the rapid growth of low-cost carriers (LCCs) and aggressive route expansion; however, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, which began in 2020, caused a steep decline in air travel and airlines face an uncertain future in regaining passengers. COVID-19 has had a far greater global impact than other recent epidemics such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which also required systematic responses from governments and airlines (Wenzel et al., 2020). When the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, changes across society and economies were implemented (Gössling et al., 2020). The air transport industry has been one of the worst affected industries in this context, and the prospects for restoring it to its pre-COVID-19 conditions are uncertain (Albers and Rundshagen, 2020).

The air transport industry provides global connections between trade, tourism, and investment, and it is profoundly affected by external factors, such as the spread of infectious diseases, exchange rates, and oil prices. Outbreaks of infectious diseases such as SARS and MERS had a short-term effect on the industry in 2003 and 2015, respectively. While the impacts of SARS and MERS were restricted to northeast Asia and the Middle East, respectively, COVID-19 has had a global impact with long-term implications.

In South Korea, airlines overcame crises such as the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD)1 in China and the Korean travelers’ boycott of Japan2 by establishing alternative routes that resulted in increased overall air passenger demand. However, the COVID-19 pandemic is more difficult to overcome, as it can only be mitigated with the development of vaccines and treatments to curb its spread. This study analyzes the responses of passengers, airlines, airports, and governments to the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, we analyze and present the changes in business strategies and the status of the implementation of airport and governmental policies. Based on the study results, we suggest policy directions for the air transport industry during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods.

This paper defines the research problem in Section 1 and the analytical background in Section 2. Section 3 presents the methodology used, and Section 4 presents the study results. Finally, Sections 5, 5 and 6 present the discussion and conclusions.

1.1. Literature review

1.1.1. Passenger responses to COVID-19

International travel restrictions, the contraction of economic activities, and changes in transportation behavior hinder the restoration of pre-pandemic demand levels, even after countries have lifted lockdowns and domestic travel restrictions (OECD, 2020). Although country-specific travel restrictions have helped to reduce the impact of the pandemic (Chinazzi et al., 2020; Oum and Wang, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), the air transport industry has been drastically affected.

Air transport is classified into passenger and cargo, and the air cargo sector has suffered comparatively less than the passenger sector, which is more sensitive to external influences (Chi and Baek, 2013; Li, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Gudmundsson et al. (2020) predicted that the cargo sector would recover before the passenger sector; moreover, their study suggests that passenger demand will recover in about 2.4 years with a minimum of 2 years and a maximum of 6 years, and the cargo sector will recover in about 2.2 years with a minimum of 2 years and a maximum of 3 years. A follow-up study suggests that cargo transport in Europe and the Asia Pacific will recover in about 2.2 years, and in North America in about 1.5 years (Gudmundsson et al., 2021).

Despite these findings, the period required for the recovery of air passenger demand remains uncertain because of the lack of understanding on how long the disease spread would continue. There was an overall 60% reduction in air passengers for both the international and domestic markets in 2020 compared to 2019 (ICAO, 2021) as a result of entry restrictions, policies, and a sharp decrease in willingness to travel. Studies have shown that the intention to travel by air has decreased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, even for those who preferred traveling by air before the pandemic. Beck and Hensher (2020) reported that 78% of Australian households changed their travel plans, with young people and low-income families being the most affected. The Korea Airport Corporation (KAC; 2020a) surveyed 1000 people on their willingness to travel abroad in May 2020 and found that 60% of the respondents did not intend to use air transportation until the development of medicines and vaccines. In this situation, rebuilding consumer confidence and reducing perceived threats are key to the recovery of air passenger travel (Lamb et al., 2020; Sotomayor-Castillo et al., 2020).

However, the findings of the survey conducted in November 2020 differ from those of previous surveys. After the development of a vaccine, the willingness to travel increased significantly to over 70% (KAC, 2020b), while another survey conducted on 1000 domestic and foreign passengers showed a marked increase in the number of people who would consider international travel, if travel bubbles were agreed upon (11.2% → 41.6% for Korean nationals, 20.8% → 72.2% for foreign nationals) (CAPA, 2020). In addition, flight-to-nowhere tour packages have been well-received recently, and overseas travel products have been successfully sold through home shopping channels, thereby demonstrating the potential for passenger demand to recover rapidly after the COVID-19 pandemic (TBS, 2020). To ensure safe travel under the present circumstances, passengers want to maintain social distancing and hygiene and receive infection alert information before boarding, and while inside an aircraft (Samanci et al., 2021).

1.1.2. Airline and policy responses to COVID-19

Passengers' willingness to travel may be restored if infection concerns can be reduced through vaccine distribution and air travel safety awareness. Preventing the spread of infectious diseases not only helps the aviation industry, but it also protects people's health (Tanriverdi et al., 2020). Recently, studies have been conducted on the response methods and strategies adopted by airports and airlines to protect health in the post-COVID-19 era from the aspect of the liability of airlines for passenger safety (Naboush and Alnimer, 2020), aircraft cabin turnaround procedures (Schultz et al., 2020), point-to-point long-haul flight business models (Bauer et al., 2020), seat assignments that follow social distancing (Salari et al., 2020), and passenger flow management in airports (Dabachine et al., 2020; Tuchen et al., 2020). Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, passenger processing strategies of airlines and airports changed from “the fastest” approach to “the safest” approach (Sun et al., 2021).

However, COVID-19 persists, and owing to high uncertainty and volatility, it is difficult to predict the future, and traditional response methods and strategies may not be able to help airlines recover. In 2020, over 40 commercial airlines failed or completely ceased operation, and the pandemic has even affected larger airlines (CNBC, 2020). The impact of the reduction in international air traffic and capacity due to cross-border travel restrictions can still be felt (IATA, 2020a). Sobieralski (2020) suggests that recovery following the airline employment shock will take between four and six years.

Historically, airlines have responded to short-term crises through contraction and consolidation (Budd et al., 2020). Maneenop and Kotcharin (2020) suggest measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of finance, employment, airport usage charges, and administration (re-routing, re-scheduling, etc.). However, the current crisis in the aviation industry is more severe and prolonged than previous crises, such that the existing countermeasures have made it more challenging to ensure its future survival and sustainability. Such crises may continue to occur in the future; hence, airlines should prepare mid-to-long-term countermeasures by looking at the expected mechanisms and possibilities of industry shocks (Brown and Kline, 2020).

There are several different approaches that airlines can adopt for getting out of this crisis, depending on their respective economic, regulatory, and social environments (OSM, 2020). Wenzel et al. (2020) present a company's management strategy in crisis situations via four major categories: retrenchment, perseverance, innovation, and exit. Albers and Rundshagen (2020) suggest a strategic response situation for major European airlines based on these four categories. Retrenchment summarizes measures that aim to reduce overhead and asset costs. Perseverance refers to measures aiming to preserve the status quo of the organization and its activities. Innovation refers to strategic renewal of the organization during the crisis. Exit refers to the discontinuation of an organization's activities (Albers and Rundshagen, 2020).

In addition to these efforts, government policy measures are essential. The air transportation industry requires a great deal of government intervention because it is closely linked to many other economic activities (OECD, 2020). Abate et al. (2020) also suggest that the role of government and public authorities is crucial for the future development of the aviation industry. Governments around the world have intervened in economic activities through various types of aid to support airlines and avoid any aviation industry bankruptcy filings (Statista, 2020). Support measures for the air transportation industry are similar worldwide and largely classified in three ways: untargeted support schemes including job retention; sectoral schemes such as subsidies to the aviation industry; and firm-specific support measures such as nationalization (OECD, 2020).

The biggest issue for the air transport industry post-pandemic is uncertainty; hence, it is necessary to develop long-term countermeasures that recognize its importance (Linden, 2021). Linden (2021) introduced a three-step process to embrace uncertainty: sensing, seizing, and transforming. Airlines and the government should sense the responses of passengers and internal and external environmental changes, seize new opportunities, and transform the industry to aim for turnaround outcomes. Sun et al. (2021) suggested several research topics to analyze and overcome the crisis: richer datasets, disease-specific models, verification of results in real environments, tolerability of passengers, international collaboration, travel bubbles, cargo-centric business, long-term impacts of deglobalization, environment, and government support, and preparation for future pandemics.

2. Materials and methods

This paper observes the South Korean experience of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 across the range of passengers, airlines, and policy responses. We analyzed passenger response and airline route changes using flight operation raw data for 2019 through 2020 to define a before- and after-COVID-19 pandemic comparison.3 Raw flight operations data, known as tower logs, include the departure/arrival airport (route), flight number, scheduled and actual departure (arrival) time, number of passengers, cargo weight, etc. (Kim and Bae, 2021; Kim and Park, 2021). We received the data from Incheon international airport Corporation (IIAC) and Korea Airport Corporation (KAC), which manage the other airports in South Korea. Using data from departure/arrival airport (route) and number of passengers, we performed exploratory data analysis between the daily/weekly demand and COVID-19 confirmed cases, compared decreases in the patterns of air passenger demand by country according to the spread of COVID-19, and analyzed changes in airlines’ route development strategies.

We analyzed and summarized the strategic responses of airlines in four categories (retrenchment, perseverance, innovation, and exit), as suggested by Albers and Rundshagen (2020). In terms of policy responses, we looked at the quarantine system at Incheon international airport (ICN), along with cases of Korean government support for airlines. Information gathering of the strategic responses of South Korean airlines and policy responses of the government and airports included a review of the existing literature in academic journals, government organizations, magazines, webpages, and various news media. Table 1 shows the data and methods of this study.

Table 1.

The study data and methods to analyze passenger, airline, and policy responses.

| Stakeholder | Response | Data | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger | Domestic passengers | Raw flight operations data including airport and airline code, origin and destination, and number of passengers (2019–2020); Daily COVID-19 confirmed cases of South Korea (01/20/2020–12/31/2020) |

Exploratory data analysis between passenger demand and COVID-19 confirmed cases |

| International passengers | |||

| Airline | Domestic & international routes change | Route comparison between before and after COVID-19 outbreak | |

| Management strategies | Information from academic journals, government organizations, webpages, magazines, etc. | Gathering data, comparison, and summarization | |

| Government & airport | Aviation industry support policies | ||

| Airport quarantine |

3. Results

3.1. Passenger responses to the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea

3.1.1. Domestic air passenger responses

International air passenger demand declined by more than 90% since its sharp drop in late January 2020. However, domestic demand has repeatedly increased or decreased following COVID-19 confirmed cases in South Korea (Table 2 and Fig. 1 ). In 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea contained three spikes, in February, August, and December. During these spikes, domestic demand responded in line with the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Factors such as COVID spread to other countries, diplomatic relations, and immigration restrictions have meant that the international demand has not seen a recovery. However, if the domestic situation improves, a recovery is expected to a certain extent. When comparing the first and second spikes, we confirmed that the recovery rate after the second spike was relatively faster when compared to the first. Domestic passenger demand recovered to 2019 levels based on a seven-day moving average taken twice during the first period, just prior to the second and third spikes in August and December. It took about three months to get back to 2019 levels after the first spike in February, although the number of confirmed cases did not increase significantly. However, after the second spike in August, it took less than one month to recover to 2019 levels, despite large numbers of daily confirmed cases. A rapid demand recovery is expected in the future as the number of COVID-19 cases decreases.

Table 2.

Changes in air passenger demand in South Korea in 2020.

| 20Q1 | 20Q2 | 20Q3 | 20Q4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | 5,366,379 (−29.0%) | 5,249,281 (−37.8%) | 7,143,032 (−14.1%) | 7,405,346 (−14.6%) | 25,164,038 (−23.7%) |

| International | 12,496,314 (−45.6%) | 472,470 (−97.9%) | 649,145 (−97.2%) | 621,494 (−97.2%) | 14,239,423 (−84.2%) |

| Total | 17,862,693 (−41.5%) | 5,721,751 (−81.5%) | 7,792,177 (−75.0%) | 8,026,840 (−73.8%) | 39,403,461 (−68.0%) |

Note: Domestic (Departure), International (Departure + Arrival).

Source: Raw flight operations data of South Korea (2019–2020).

Fig. 1.

Changes in domestic and international air passenger demand following the COVID-19 outbreak.

3.1.2. International air passenger responses

Unlike domestic demand which reacts sensitively to increases or decreases in COVID-19 in South Korea, international demand continued to decline due to the worldwide situation. We analyzed the demand in three countries—Japan, China, and the United States—to find that international air passenger demand is sensitive not only to domestic situations, but also to various external factors. We compared the patterns of air passenger demand reduction in the first quarter of 2020 for this analysis.

In the case of Japan, air passenger demand had decreased significantly before the COVID-19 outbreak due to the country's export restrictions with Korea announced in July 2019 (Kim, 2019; Yamada and Obayashi, 2019). China then confirmed the first COVID-19 case in December 2019, and air passenger demand plummeted from the end of January as the pandemic spread to the United States in March 2020 (Fig. 2 ). This confirms that air passenger demand responds not only to crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, but also to socio-economic situations, such as the South Korean boycott of Japan. However, even if the situation improves, it is unclear whether the recovery will be immediate. International air passenger demand is at an all-time low, regardless of the global trend. When observing the domestic demand patterns presented in the previous section, we can see that demand responds immediately as the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases increases or decreases, and the recovery cycle shortens. Unlike domestic flights, the demand recovery for international flights can be expected only when both terminal-point countries are safe. Social awareness is also important. Fortunately, there are many people who wish to resume their travel under the assumption that COVID-19 will be eradicated. In January 2021, about 5000 people booked Vietnam travel packages sold through home shopping channels. This travel package is valid for one year from the time that the borders between Korea and Vietnam open for overseas travel (Pulse, 2021).

Fig. 2.

Changes in air passenger demand of Japan, China, and the United States in the first quarter of 2020.

Analyzed from weekly average daily passengers (Monday to Sunday), based on ISO8601 standards (comparison between 2018.12.31. ~ 2019.03.31., and 2019.12.30. ~ 2020.03.29.)

3.2. Airline responses to the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea

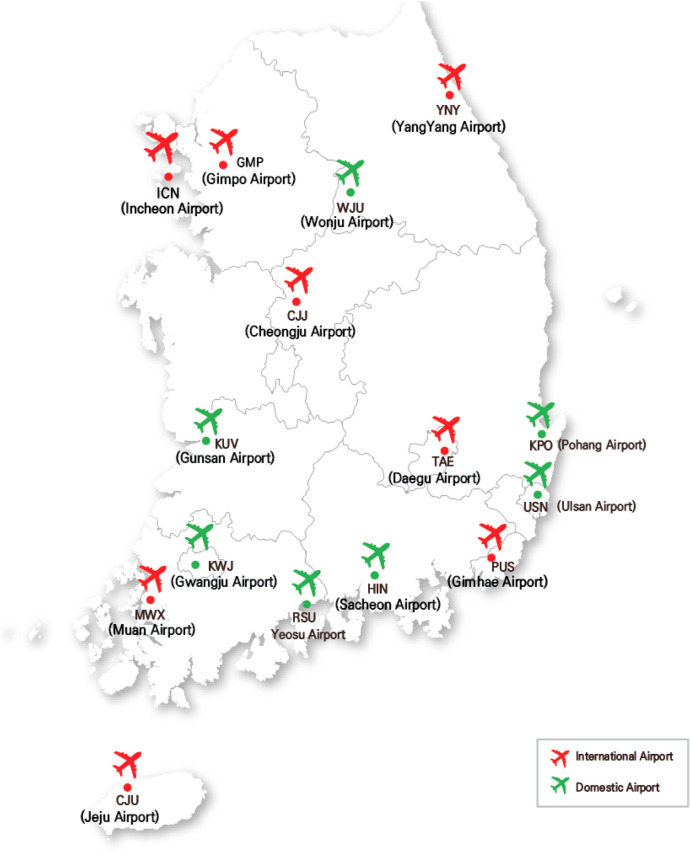

In South Korea, nine airlines, including two full-service carriers (FSCs), KAL and AAR, and seven LCCs (ABL, ASV, ESR, JJA, JNA, TWB, and FGW) were competing with the airlines EOK and APZ in 2020, while preparing to launch their flight services in 2021. There are a total of 15 airports in South Korea, consisting of eight international airports (ICN, GMP, CJU, PUS, TAE, CJJ, MWX, YNY) and 7 domestic airports (HIN, KPO, KUV, KWJ, RSU, USN, and WJU) (please see the Appendix for the names of the airlines and airports).

3.2.1. Domestic and international routes

As discussed in the previous sections, both domestic and international air passenger demands have been extremely low during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the domestic market is in a better situation than the international market. South Korean airlines turned to the development of domestic flights, launching new routes, as it was difficult to operate international flights within the pandemic. The South Korean domestic air passenger market is composed of GMP and CJU with connecting flights to international flights into ICN. Fig. 3 shows a comparison between the domestic routes in January 2020 and December 2020. South Korean airlines halted the operation of connecting flights (ICN-PUS, ICN-TAE) after a sharp drop in international passenger demand and instead launched new routes (GMP-KPO, YNY-KWJ, YNY-PUS). The routes (GMP-HIN, CJU-HIN, and CJU-MWX) that disappeared since January were non-profitable routes operated by the two FSCs.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of domestic routes between January 2020 and December 2020.

FSCs can operate aircraft capable of long-distance travel and continue operations on indispensable international routes. However, LCCs use aircraft such as B737s and A320s that can only operate on short-distance routes. Therefore, they cannot be used on alternative routes other than domestic flights, when it became impossible to operate main routes through to China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. As presented in Table 3 , the FSC domestic flight operations decreased when compared to the previous year, although LCC flights increased. Particularly, TWB focused on routes to Japan in 2019 without operating many domestic routes. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, TWB moved to domestic routes faster than other airlines.

Table 3.

Changes in domestic passenger airline in 2020

Unit: passengers, %.

| Airline | 20Q1 | 20Q2 | 20Q3 | 20Q4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAL | 1,120,513 (−32.5) | 871,713 (−56.7) | 966,229 (−50.8) | 1,068,780 (−44.4) | 4,027,235 (−46.7) |

| AAR | 1,068,653 (−28.8) | 1,021,667 (−37.2) | 1,125,641 (−29.1) | 1,046,673 (−36.3) | 4,262,634 (−32.9) |

| ABL | 667,787 (−37.4) | 746,623 (−30.9) | 953,037 (−10.6) | 996,149 (−11.8) | 3,363,596 (−22.5) |

| ASV | 81,002 (−) | 182,885 (−) | 296,340 (−) | 377,561 (316.1) | 937,788 (933.4) |

| ESR | 568,209 (−22.8) | Ceased | Ceased | Ceased | 568,209 (−81.9) |

| JJA | 807,388 (−29.1) | 901,592 (−25.5) | 1,264,844 (1.0) | 1,351,320 (6.3) | 4,325,144 (−11.2) |

| JNA | 443,354 (−38.3) | 649,437 (−34.7) | 1,256,983 (38.5) | 1,274,331 (33.3) | 3,624,105 (1.3) |

| TWB | 580,250 (−21.5) | 844,595 (13.0) | 1,226,433 (67.3) | 1,258,720 (55.2) | 3,909,998 (29.0) |

| FGW | 29,223 (−) | 30,769 (−) | 53,525 (−) | 31,812 (46.3) | 145,329 (568.1) |

| Total | 5,366,379 (−29.0) | 5,249,281 (−37.8) | 7,143,032 (−14.1) | 7,405,346 (−14.6) | 25,164,038 (−23.7) |

Source: Raw flight operations data of South Korea (2019–2020).

In the case of international routes, all South Korean airlines showed a reduction of above 90% in demand from the second quarter (Table 4 ). In January 2020, there were 7.6 million passengers and 183 routes; however, the number of passengers fell to 0.2 million and 110 routes in December (Fig. 4 ). ESR and FGW's international routes have been closed since March 2020, while the other airlines have operated very few international flights.

Table 4.

Changes in international passenger airline in 2020

Unit: passengers, %.

| Airline | 20Q1 | 20Q2 | 20Q3 | 20Q4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAL | 2,971,308 (−41.0) | 190,446 (−96.2) | 231,170 (−95.4) | 211,026 (−95.7) | 3,603,950 (−82.0) |

| AAR | 1,966,781 (−41.7) | 120,574 (−96.5) | 149,997 (−95.7) | 153,122 (−95.6) | 2,390,474 (−82.7) |

| ABL | 404,137 (−58.7) | Ceased | 3365 (−99.6) | 6072 (−99.1) | 413,574 (−88.0) |

| ASV | 213,390 (−59.7) | 688 (−99.9) | 2251 (−99.5) | 5512 (−98.5) | 221,841 (−87.8) |

| ESR | 412,129 (−51.8) | Ceased | Ceased | Ceased | 412,129 (−86.3) |

| JJA | 1,096,267 (−49.5) | 13,127 (−99.3) | 9384 (−99.6) | 9446 (−99.5) | 1,128,224 (−86.5) |

| JNA | 648,147 (−58.3) | 3116 (−99.8) | 7378 (−99.4) | 7775 (−99.3) | 666,416 (−86.9) |

| TWB | 686,937 (−47.3) | 562 (−100.0) | 3674 (−99.7) | 9598 (−99.2) | 700,771 (−85.6) |

| FGW | 7687 (−) | Ceased | Ceased | Ceased | 7687 (501.00) |

| Total | 8,406,783 (-46.8) | 328,513 (-97.8) | 407,219 (-97.3) | 402,551 (-97.2) | 9,545,066 (-84.2) |

Source: Raw flight operations data of South Korea (2019–2020).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of international routes and passenger transport between January 2020 and December 2020.

3.2.2. Strategic responses of South Korean airlines

South Korean airlines have been consistent in their efforts to overcome the pandemic crisis amid the continuous decrease in passenger demand. This section presents the major response strategies adopted by South Korean airlines and classifies them into the four categories suggested by Albers and Rundshagen (2020).

Strategies that fall into the retrenchment response category include voluntary retirement, rotational unpaid leave, working from home, wage cutbacks, layoffs, and closed and suspended domestic and international routes. All nine airlines have implemented these strategies (Kim and Choi, 2020). The perseverance response category includes government subsidies and loans, increases in paid-in capital, asset sales (real estate, company housing, businesses), and promotions. The government provided KRW 1.2 trillion to KAL and AAR in emergency assistance in April 2020 (Choi, 2020a), and KRW 40 billion to LCCs TWB, ASV, and ABL as uncovered loans (Park, 2020). Most airlines are fighting mass unemployment through the government's Employment Maintenance Subsidy (Ryu, 2020), while KAL secured funds through the sale of its in-flight meal business, real estate, and real estate mortgage loans (Korean Air, 2020; Cho, 2020; En24, 2020). In addition, airlines eliminated ticket change and cancellation fees, while selling prepaid tickets to attract air passengers (Back, 2020).

KAL and AAR's transformations into cargo transport-oriented businesses represent innovative response strategies (Song, 2020a). In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, many factories shut down, and the demand for air cargo decreased because of global economic contraction (FlightGlobal, 2021). However, as non-face-to-face transactions increased due to the ongoing pandemic, and the demand for ICT products such as semiconductors recovered, supply shortages became more serious as demand increased. Since belly cargo accounted for approximately 50% of air cargo (IATA, 2020b), the number of flights sharply reduced, and the cargo supply was insufficient. Accordingly, KAL and AAR, the world's largest air freight carriers, fully rearranged their available resources, in addition to their existing freight transport capabilities, by converting passenger planes to freighters and loading freight on passenger seats (Choi, 2020b; Pulse, 2020a; Yim, 2020). Air cargo has played a vital role in delivering essential medicines and medical equipment (including spare parts and repair components) and ensured proper functioning of global supply chains for the most time-sensitive materials (IATA, 2020c; Sun et al., 2021). As a result, KAL and AAR recorded 14.6% and 4.6% increases in air freight demand, respectively, in 2020 compared to the previous year (KAC, 2021). Moreover, KAL achieved a profit in 2020 along with a cost reduction through retrenchment and perseverance strategies. Increases in air freight rates also had significant impacts. The TAC index of Hong Kong–North America increased from $3.14 in January 2020 to $7.50 in December 2020 (Aircargo News, 2021).

It is difficult for LCCs to change their portfolios and enter the cargo business because they mainly operate small passenger aircraft, such as B737s and A320s. They responded to the crisis by increasing the number of new domestic routes. This response strategy is an example of innovation response. There are strategic responses in the exit response category in South Korea as well. JJA signed an acquisition contract for ESR in December 2019, but the takeover fell through in July 2020, as the airline was in a state of full capital erosion (Jin, 2020). In addition, AAR was scheduled for acquisition by Hyundai Development Corporation (HDC), but the takeover fell through in September 2020 (Herh, 2020); KAL announced the acquisition of AAR in November 2020 (Kim, 2021). If KAL receives approval from the Korean government, the airline will emerge as the world's tenth largest airline by fleet size (The Korea Times, 2020). The response strategies of the airlines to COVID-19 are summarized in Table 5 .

Table 5.

South Korean airlines’ response to the COVID-19 crisis.

| Response category | Airline prevalence |

|---|---|

| Retrenchment |

|

| Perseverance |

|

| Innovation |

|

| Exit |

|

Note: Summary of South Korean airlines' response presented in section 4.2.2.

3.3. Policy responses to COVID-19 in South Korea

In South Korea, COVID-19 spread rapidly in the early stages of the pandemic, but it is now under control as compared to some other countries. However, due to the nature of the air transport business, the difficulties faced by airlines have become more pronounced (Dube et al., 2021). In most countries, there is no dispute that aviation will play an important role in reviving their national economies post-COVID-19 (Abate et al., 2020; Macilree and Duval, 2020). The Korean government's policy is to stop the spread of the disease and help the industry to recover by establishing an airport quarantine system and providing support to the air transportation industry.

The Korean government's support of the air transportation industry is not very different from that of other countries. It prepared and implemented policy responses, such as deferral of slot collections, reduction and exemption of airport charges, subsidies, loans, and airline ticket prepayments. In addition, they have supported related industries, such as ground handling companies, duty-free shops, and airport bus companies with employment maintenance subsidies and rent reduction measures. The Korea Development Bank is a government-owned bank that invested 800 billion KRW (about $730 million USD) in KAL's acquisition of AAR (Pulse, 2020b).

However, the most important factor in the air transportation industry's recovery is the restoration of demand. Even if the government continues to provide financial support while the pandemic continues, it is difficult to expect a recovery in air transportation demand. The spread of infectious diseases between countries is mostly through airports, hence, quarantine management is very important (Forsyth et al., 2020; Serrano and Kazda, 2020; Tabares, 2021; Sun et al., 2021). The Korean government has systematized epidemic control at airports using the following three methods:

-

1)

Organization and response of government task force and integration of international airports

In the early days of the spread of COVID-19, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) organized a task force to design support and operation measures. Out of eight international airports, only ICN allowed passengers to enter the country, and human resources were concentrated in one place to prevent the progression of COVID-19 (MOLIT, 2020a).

-

2)

Response to infections at the airport

Incheon International Airport Corporation (IIAC) has responded by establishing a “smart epidemic control team” to enforce immediate responses at epidemic control sites. The Airports Council International (ACI) has been certified in the Asia Pacific for the Airport Health Accreditation (AHA) program for the first time (International Airport Review, 2020). In addition, amid the ongoing crisis, IIAC consulted an epidemic control system for airports at the Indonesian airport corporation (PT Angkasa Pura 1) on the response against COVID-19 (MOLIT, 2020b).

-

3)

Airport departure and arrival procedures

To prevent the spread of COVID-19 at departure and in flight, ICN carries out a screening process in three different stages (check-in, entry into security zone, and boarding gate). Masks are mandatory for all passengers and staff at the airport, and smart facilities such as kiosks have been installed to minimize face-to-face contact. A COVID-19 test center was set up inside the airport to test departing passengers and issue health status confirmation for outbound air passengers in one stop (IIAC, 2020a). ICN has implemented a special arrival procedure with the establishment of an isolated arrival zone and special immigration procedures for people arriving from high-risk countries. The contact details of both foreign and Korean entrants are collected and they are required to submit a self-diagnosis result once a day through a mobile application, thereby strengthening follow-up control. In addition, transportation for foreign entrants is separate, and they use exclusive transportation taxis (IIAC, 2020b).

4. Discussion

We analyzed passenger, airline, and policy responses following the COVID-19 outbreak in the preceding section. The aviation industry is going through a very difficult time with an unprecedented decline in demand. We confirmed that airlines in crisis are trying to overcome their problems through cost reductions and portfolio changes, and the South Korean government and airports are making efforts to help the aviation industry recover through airline support and reorganization of quarantine systems. In this section, we discuss the short-to long-term changes in the air transport industry and strategic response plans after 2021 based on the stakeholders’ response to COVID-19.

The expectation is that air passenger demand will not fully recover as the global COVID-19 pandemic continues. However, South Korean domestic demand has been increasing in line with decreases in the number of COVID-19 cases. We expect that this pattern will repeat with decreasing recovery times. Considering the recent domestic demand pattern, the popularity of no-destination flights, and the unexpected popularity of travel packages through home shopping channels, we expect a recovery in air passenger demand. In China, Japan, Russia, and the United States, domestic air demand is also gradually recovering (Sun et al., 2020, 2021; Czerny et al., 2021). To facilitate an increase in international demand, passenger awareness of COVID-19 situations in other countries is very important, but awareness of quarantine policies and reliability differs from country to country. Quarantine-free travel corridors should only be established between countries with similar COVID-19 incidence and efficient real-time disease surveillance (Sharun et al., 2020). The South Korean government should increase trust by promoting infectious disease safety measures and providing transparent information to restore international air passenger confidence, and make efforts to resume routes with other countries by using a travel bubble strategy.

South Korean airlines are trying to overcome the crisis through transitioning to domestic flights as well as expanding freight transportation and mergers and acquisitions. In South Korea, large-scale industrial restructuring is taking place, such as the merger of KAL and AAR. The two companies are the largest in South Korea. JNA is a subsidiary of KAL, and ABL and ASV are subsidiaries of AAR. The passenger shares of these five companies peaked at 65.5% in 2020. KAL's acquisition of AAR is on track and awaits approval from the antitrust authorities of South Korea. The Korean Fair Trade Commission is paying close attention to whether the merger of KAL and AAR will result in a monopoly or oligopoly (Yonhap News Agency, 2021). In this pandemic struck global economy, the merger between South Korea's two largest airlines, KAL and AAR, presents an opportunity to overcome the current crisis by reforming the cost structure of the aviation industry of South Korea.

In the long-term, it is very important for airlines to diversify their business models and strategies. KAL recorded a profit in 2020 by focusing on air cargo transportation, including vaccine cold chain delivery, while reducing costs (IATA, 2020d; Shin, 2021). In addition, airlines are trying to generate revenue in areas other than air transport. JNA sold over 10,000 in-flight themed meals in November 2020, one every 4 min, while Thai Airways (BKK) and Canada's Air North (ANT) have made similar moves (Yim, 2021). Singapore Airlines (SGX) provided a package for meals on parked planes (BBC, 2020). The first revenue source for airlines is passenger and cargo transportation; however, airlines need alternatives that can withstand crises.

In terms of policy responses, the South Korean government's support of the aviation industry is not very different from other countries. However, what is noteworthy in the South Korean policy response is that the government is trying to minimize the imported COVID-19 cases by strengthening quarantine at ICN. ICN is the first in the Asia-Pacific region to gain accreditation under the ACI's AHA program for quarantine procedures (International Airport Review, 2020). Quarantine officials guide those who arrive at the ICN in accordance with the systematized epidemic control system, thus minimizing importation of COVID-19 cases without closing borders (Song, 2020b).

Although it would be undesirable, should another global crisis arise, the aviation industry now has response capabilities to cope with it. In general, industries do not establish response plans for low-probability events (Linden, 2021); however, in an uncertain global society, when and where crises may occur is unknown. The experience of the COVID-19 quarantine system implementation at the ICN will be a great asset to governments and airports in establishing proactive response plans to other crises.

5. Conclusions

The air transport industry has continuously undergone a stagnation-recovery cycle according to changes in the internal and external environments. The COVID-19 outbreak has caused a very long stagnation period such that the future seems uncertain. We confirmed that air passengers respond sensitively to internal and external environments based on the air passenger responses of South Korea. It is particularly difficult for international passenger demand to recover due to the large number of confirmed cases worldwide. In contrast, South Korean domestic demand has responded immediately with an increase or decrease in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, gradually shortening the recovery cycle. We can expect a recovery of air passenger demand through the recovery of consumers’ willingness to travel along with a reduction in global cases and better vaccine distribution.

As the aviation industry has suffered considerable damage due to the pandemic-induced reduction in air passenger demand, the government and airlines are pursuing various strategies to mitigate the crisis. South Korean airlines have responded to the COVID-19 crisis through a multitude of strategic responses, including retrenchment, perseverance, innovation, and exit; the South Korean government has concurrently decided to provide emergency support to the aviation industry, such as financial backing and payment deferment of usage fees, aid in developing new markets to enhance airline competitiveness, and other additional measures. In addition, the Korean government is trying to minimize the inflow of COVID-19 through the border by unifying immigration control to ICN and implementing special immigration processes such as continuous management by mobile application.

In particular, the KAL-AAR acquisition, diversification of business models, surplus through cost reduction, concentrating on cargo, unification of immigration to ICN, and the new quarantine system show the mitigating efforts of South Korean airlines and the government. We envision the findings of this study to help establish short- and long-term strategies for airlines and governments in global aviation networks. Airlines and governments should transform the industry by aiming for turnaround outcomes and sustainability.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, further research is necessary to continuously monitor the response of passengers, the industry, and governments and to share relevant information. In this study, we presented the exploratory data analysis of passengers’ response to COVID-19 in 2020. We expect a quantitative analysis of the causal relationship between COVID-19 and air passenger demand reflecting vaccination, quarantine fatigue, and so on, to be conducted with accumulation of data to prepare for a post-pandemic world.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Myeonghyeon Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Jeongwoong Sohn: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Korea Agency for infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant (21ACTO-B151239-03) funded by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.

Footnotes

In 2016, when the South Korean government decided on the placement of THAAD missiles, the Chinese government immediately took corrective action that was mainly centered on sanctions on Hallyu (the Korean wave) known as the han-han-ryeong (a government ban on Hallyu) (Kwon, 2017).

In 2019, South Koreans started boycotting Japanese brands and traveling to Japan when the Japanese government decided to restrict the export of chemical products used by South Korean companies to make cell phones and electronic displays.

In section 4.1.2., we compare weekly average daily passengers of Japan, China, and United States in the first quarter of 2019 and 2020 based on ISO8601 standards (Monday to Sunday). We compare 2019 (2018.12.31. ∼ 2019.03.31.) and 2020 (2019.12.30. ∼ 2020.03.29.), and one day's 2018 data are included.

Appendix.

1.Airports in South Korea

2.Airlines in South Korea

| FSC/LCC/HSC | ICAO Code | IATA Code | Airline Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Service Carrier | KAL | KE | Korean Air |

| Full-Service Carrier | AAR | OZ | Asiana Airlines |

| Low-Cost Carrier | ABL | BX | Air Busan |

| Low-Cost Carrier | ASV | RS | Air Seoul |

| Low-Cost Carrier | ESR | ZE | Eastar Jet |

| Low-Cost Carrier | JJA | 7C | Jeju Air |

| Low-Cost Carrier | JNA | LJ | Jin Air |

| Low-Cost Carrier | TWB | TW | T’way Airline |

| Low-Cost Carrier | FGW | 4V | Fly GangWon |

| Low-Cost Carrier | EOK | RF | Aero – K (Plans to Launch) |

| Hybrid Service Carrier | APZ | YP | Air Premia (Plans to Launch) |

References

- Abate M., Christidis P., Purwanto A.J. Government support to airlines in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Air Korean. Korean Air sold its in-flight meal board business for 9906 billion won. 2020. https://www.en24news.com/2020/08/korean-air-sold-its-in-flight-meal-board-business-for-9906-billion-won.html

- Aircargo News Airfreight rates-Baltic Exchange Airfreight Index. 2021. https://www.aircargonews.net/data-hub/airfreight-rates-tac-index/

- Albers S., Rundshagen V. European airlines' strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (January-May, 2020) J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;87 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back J. YTN news; 2020. Airlines with ‘lack of Cash’ Sell Prepaid Tickets.https://www.ytn.co.kr/_ln/0102_202004211517138005 (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Bauer L.B., Bloch D., Merkert R. Ultra Long-Haul: an emerging business model accelerated by COVID-19. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC Singapore Airlines sells out meals on parked plane. 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54519322?utm_campaign=Below%20the%20Fold&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=97356723&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_pXckYlmSNe4uUIRlJPHf0lzMiVIJ8y4iSHM2CLqEmr1Wt0mZyVlNTAL-zpy3fs_oBwbc83KjssE7y_5mhPzA56iV8B4vxRwaHysWKaCNA0Np5_lA&utm_content=97356327&utm_source=hs_email

- Beck M.J., Hensher D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia–The early days under restrictions. Transport Pol. 2020;96:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.S., Kline W.A. Exogenous shocks and managerial preparedness: a study of US airlines' environmental scanning before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budd L., Ison S., Adrienne N. European airline response to the COVID-19 pandemic–Contraction, consolidation and future considerations for airline business and management. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Aviation (CAPA) Incheon Airport Corporation reports results of survey on travel bubbles. 2020. https://centreforaviation.com/news/incheon-airport-corporation-reports-results-of-survey-on-travel-bubbles-1033769

- Chi J., Baek J. Dynamic relationship between air transport demand and economic growth in the United States: a new look. Transport Pol. 2013;29:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., y Piontti A.P., Mu K., Rossi L., Sun K., Viboud C. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368:395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. Nocut News; 2020. Korean Air Sells its In-Flight Meal and Duty-free Business for KRW 990 Billion.https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5401018 (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Infostock Daily; 2020. Korea Development Bank, T-Way, Air Seoul, Air Busan 40 Billion Won Support.http://www.infostockdaily.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=89506 [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. Yonhap News Agency; 2020. Korean Air Seeks to Convert Passenger Jets into Cargo Planes amid Rising Demand.https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20200720006600320 [Google Scholar]

- CNBC Over 40 airlines have failed so far this year-and more are set to come. 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/08/over-40-airlines-have-failed-in-2020-so-far-and-more-are-set-to-come.html

- Czerny A.I., Fu X., Lei Z., Oum T.H. Post pandemic aviation market recovery: experience and lessons from China. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dabachine Y., Taheri H., Biniz M., Bouikhalene B., Balouki A. Strategic design of precautionary measures for airport passengers in times of global health crisis COVID-19: parametric modelling and processing algorithms. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube K., Nhamo G., Chikodzi D. COVID-19 pandemic and prospects for recovery of the global aviation industry. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- En24 Korean Air sold its in-flight meal board business for 9906 billion won. 2020. https://www.en24news.com/2020/08/korean-air-sold-its-in-flight-meal-board-business-for-9906-billion-won.html

- Forsyth P., Guiomard C., Niemeier H.M. Covid-19, the collapse in passenger demand and airport charges. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Flight. Korean Air reports $213 million operating profit for 2020. 2021. https://www.flightglobal.com/airlines/korean-air-reports-213-million-operating-profit-for-2020/142285

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020;29:1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson S.V., Cattaneo M., Redondi R. 2020. Forecasting recovery time in air transport markets in the presence of large economic shocks: COVID-19. Available at SSRN 3623040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson S.V., Cattaneo M., Redondi R. Forecasting temporal world recovery in air transport markets in the presence of large economic shocks: the case of COVID-19. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;91 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.102007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herh M. Business Korea; 2020. HDC's takeover of Asiana Airlines falls through.http://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=51314 [Google Scholar]

- Incheon International Airport Corporation (IIAC) COVID-19 free airport. 2020. https://www.airport.kr/ap_cnt/en/svc/covid19/checkin/ch eckin.do

- Incheon International Airport Corporation (IIAC) COVID-19 response. 2020. https://www.airport.kr/co/en/cmm/cmmBbsList.do?FNCT_CODE=271

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) Air passenger forecasts (2020.4) 2020. https://www.iata.org/en/publications/economics

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) Action cargo: covid-19. 2020. https://www.iata.org/en/programs/cargo

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) Insufficient capacity dampens air cargo in August. 2020. https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-09-29-01 (2020.9)

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) Guidance for vaccine and pharmaceutical logistics and distribution. 2020. https://www.iata.org/contentassets/028b3d4ec3924cb393155c84784161ac/guidance-for-vaccine-and-pharmaceutical-logistics-and-distribution---extract.pdf

- International Airport Review Incheon becomes first Asia-Pacific airport to gain ACI Health Accreditation. 2020. https://www.internationalairportreview.com/news/125716/incheon-airport-aci-health-accreditation/

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Effects of novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) on civil aviation: economic Impact Analysis. 2021. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Documents/COVID-19/ICAO_Coronavirus_Econ_Impact.pdf Montréal, Canada.

- Jin M. Korea JoongAng Daily; 2020. Jeju Air Contemplates Walking Away from Eastar Jet Deal.https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2020/07/07/business/industry/jeju-air-eastar-jet-acquisition/20200707195100412.html [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Yonhap News Agency; 2019. Japan's Export Restriction Adds Uncertainty to S. Krean Tech Industry.https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20190701004400320 [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. The Korea Times; 2021. Korean Air to up Stock Sale to 3.3 Trillion Won for Asiana Acquisition.http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2021/01/113_302174.html [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Bae J. Modeling the flight departure delay using survival analysis in South Korea. J. Air Transp. 2021;91:101996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim T., Choi M. S. Korea doles out special employment subsidies to airline, travel biz for six months. Pulse by Maeil business news Korea. 2020 https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?year=2020&no=276095 [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Park S. Airport and route classification by modelling flight delay propagation. J. Air Transp. 2021;93:102045. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Airport Corporation (KAC) 2020. Willingness to travel abroad by period after COVID-19 (a secondary survey) (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Korea Airport Corporation (KAC) 2020. Willingness to travel abroad by period after COVID-19 (a third survey) (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon K. The dilemma of the Chinese foreign cultural policy through the ‘限韓令 (a government ban on Hallyu)’ (in Korean) The Journal of Chinese Cultural Research. 2017;37:25–49. doi: 10.18212/cccs.2017..37.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb T.L., Winter S.R., Rice S., Ruskin K.J., Vaughn A. Factors that predict passengers willingness to fly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T. A SWOT analysis of China's air cargo sector in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden E. Pandemics and environmental shocks: what aviation managers should learn from COVID-19 for long-term planning. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macilree J., Duval D.T. Aeropolitics in a post-COVID19 world. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;88:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneenop S., Kotcharin S. The impacts of COVID-19 on the global airline industry: an event study approach. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) MOLIT, Support for air transport of coronavirus COVID-19 (In Korean) 2020. http://www.molit.go.kr/atmo/USR/N0201/m_36515/dtl.jsp?id=95084869

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT) Aviation-tourism recovery forum seminar on aviation safety and recovery against COVID-19. 2020. http://www.aviation-recovery.co.kr/upload/Session%203_Woo-Ho%20Cho_IIAC.pdf

- Naboush E., Alnimer R. Air carrier's liability for the safety of passengers during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offshore and Ship Management (OSM) COVID-19's impact on the airline industry: the new reality. 2020. https://osmaviation.com/covid-19s-impact-on-the-airline-industry-the-new-reality

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) COVID-19 and the aviation industry: impact and policy responses. 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-the-aviation-industry-impact-and-policy-responses-26d521c1

- Oum T.H., Wang K. Socially optimal lockdown and travel restrictions for fighting communicable virus including COVID-19. Transport Pol. 2020;96:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Seoul Economy; 2020. Government and banks soften the application conditions for unsecured loans (in Korean)https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=101&oid=011&aid=0003709821 [Google Scholar]

- Pulse Asiana Airlines to run at halved staffing, use idled planes to deliver cargo. Pulse by Maeil business news Korea. 2020 https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?year=2020&no=304431 [Google Scholar]

- Pulse Court clears major hurdle for Korean Air-Asiana Airlines merger. Pulse by Maeil business news Korea. 2020 https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?sc=30800028&year=2020&no=1237623 [Google Scholar]

- Pulse Interpark Tour sells $9 million tickets for Vietnam tour package via shopping channel. 2021. https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?sc=30800022&year=2021&no=78926

- Ryu S. Emergency support to airlines, shipping, tourism, and restaurants directly hit by COVID-19… ‘Provide’ up to KRW 300 billion to LCCs. 2020. http://www.megaeconomy.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=92718 (In Korean). Mega Economy.

- Salari M., Milne R.J., Delcea C., Kattan L., Cotfas L.A. Social distancing in airplane seat assignments. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanci S., Atalay K.D., Isin F.B. Focusing on the big picture while observing the concerns of both managers and passengers in the post-COVID era. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz M., Evler J., Asadi E., Preis H., Fricke H., Wu C.L. Future aircraft turnaround operations considering post-pandemic requirements. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Traffic Broadcasting (TBS) Asiana airlines to offer ‘flights to nowhere’. 2020. http://tbs.seoul.kr/eFm/newsView.do?typ_800=J&idx_800=3405928&seq_800=

- Serrano F., Kazda A. The future of airport post COVID-19. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharun K., Tiwari R., Natesan S., Yatoo M.I., Malik Y.S., Dhama K. International travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications and risks associated with ‘travel bubbles’. J. Trav. Med. 2020;27(8) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H. Reuters; 2021. S. Korea Readies for COVID-19 Vaccine with Airport Transport Drill.https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-southkorea/skorea-readies-for-covid-19-vaccine-with-airport-transport-drill-idUSL4N2K90Y8 [Google Scholar]

- Sobieralski J.B. Vol. 5. TRIP; 2020. (COVID-19 and Airline Employment: Insights from Historical Uncertainty Shocks to the Industry). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K. Korea JoongAng Daily; 2020. Korean Air starts preparing to ship Covid-19 vaccines.https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2020/10/07/business/industry/Korean-Air-cargo-vaccine/20201007160000473.html [Google Scholar]

- Song S. Incheon Airport still battling COVID-19. The Korea Herald. 2020 http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200924000325 [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor-Castillo C., Radford K., Li C., Nahidi S., Shaban R.Z. Air travel in a COVID-19 world: commercial airline passengers’ health concerns and attitudes towards infection prevention and disease control measures. Infect. Dis. Health. 2020;26(2) doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista Types of government aid to airlines due to COVID-19 as of September 2020. 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1170560/government-aid-airlines-worldwide-covid19

- Sun X., Wandelt S., Zhang A. How did COVID-19 impact air transportation? A first peek through the lens of complex networks. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Wandelt S., Zheng C., Zhang A. COVID-19 pandemic and air transportation: successfully navigating the paper hurricane. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;94 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabares D.A. An airport operations proposal for a pandemic-free air travel. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanrıverdi G., Bakır M., Merkert R. What can we learn from the JATM literature for the future of aviation post COVID-19?-A bibliometric and visualization analysis. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Korea Times Korean Air to buy Asiana, emerges as world's 10th-largest airline. 2020. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2020/11/774_299371.html

- Tuchen S., Arora M., Blessing L. Airport user experience unpacked: conceptualizing its potential in the face of COVID-19. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wong C.W.H., Cheung T.K.Y., Wu E.Y. How influential factors affect aviation networks: a Bayesian network analysis. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2021;91 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M., Stanske S., Lieberman M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020;41 doi: 10.1002/smj.3161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Obayashi H. Japan Inc. stung by South Korean boycott. Nikkei Asia; 2019. From Beer to Travel.https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-South-Korea-rift/From-beer-to-travel-Japan-Inc.-stung-by-South-Korean-boycott [Google Scholar]

- Yim H. The Korea Herald; 2020. How Major South Korean Airlines Made Profits during Pandemic.http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200813000545 [Google Scholar]

- Yim H. The Korea Herald; 2021. Jin Air's Ready Meals Become a Hit amid Home Meal Replacements Boom.http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210121000781 [Google Scholar]

- Yonhap News Agency . 2021. Antitrust Regulator Starts Review of Korean Air's Asiana Takeover Deal.https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20210114008800320 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yang H., Wang K., Zhan Y., Bian L. Measuring imported case risk of COVID-19 from inbound international flights---A case study on China. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]