Abstract

The COVID-19 lockdown has transformed the way of life for many people. One key change is media intake, as many individuals reported an increase in media consumption during the COVID-19 lockdown. Specifically, social media and television usage increased. In this regard, the present study examines social TV viewing, the simultaneous use of watching TV while communicating with others about the TV content on various communication technologies, during the COVID-19 lockdown. An online survey was conducted to collect data from college students in the United States during the COVID-19 lockdown. Primary results indicate that different motives predict different uses of communication platforms for social TV engagement, such as public platforms, text-based private platforms, and video-based private platforms. Specifically, the social motive significantly predicts social TV engagement on most of the platforms. Further, the study finds that social presence of virtual co-viewers mediates the relationship between social TV engagement and social TV enjoyment. Overall, the study's findings provide a meaningful understanding of social TV viewing when physical social gatherings are restricted.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Media use, Social presence, Social TV

1. Introduction

In 2020, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (known in the popular press as COVID-19) evolved from an isolated disease endemic to the Wuhan, Hubei Province of China to a global pandemic [1]. In just a few months, COVID-19 dramatically changed the world, altering its very makeup and landscape in such a way that will take years to recover from before, colloquially, returning to normal [2]. In particular, COVID-19 fundamentally altered several key categories of social life, including psychological wellbeing and relational maintenance [3]. Many countries, the United States included, implemented mandatory lockdown procedures in March 2020. While different states and municipalities have since relaxed or altogether removed the lockdown proceedings, several other regions have kept them implemented in some capacity, especially with the spread of various variants of the disease [4].

COVID-19, coupled with the mandatory lockdown procedures, transformed daily behaviors. A concerning socioemotional issue that resulted from these changes is social isolation [5]. The World Health Organization [1] warns that social isolation can be damaging to an individual's health by increasing feelings of loneliness, as it is associated with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide. To deal with feelings of loneliness and social isolation during COVID-19, many individuals relied on various media, such as social media [6,7], to remain engaged and active in a lockdown world. Between March 2020 and May 2020, The Harris Poll [8] found between 46% and 51% of U.S. adults reported greater social media usage on account of the outbreak and subsequent lockdowns. A follow-up survey in May 2020 found that 60% of those aged 18 to 34, 64% of those aged 35 to 49, and 34% of those aged 65 and older reported an increase in their use of social media [8].

Of various media use, social TV viewing is of particular interest in this investigation. The core idea of social TV viewing is generally based on the simultaneous act of watching TV and communicating with others via communication technologies about the TV content [9]. For example, when people are watching a sporting event on television, they can communicate about the game with others via WhatsApp or by posting about the program on their Twitter Timeline. Simply put, this type of media use can be understood as social TV viewing. Considering that social TV viewing combines consumption of two different media, which have increased during the lockdown [8,10], it is important to examine this media use behavior when physical social gatherings are restricted.

Given that there are several communication technology platforms for social TV viewing to communicate with others (e.g., social media, private message applications), the present study seeks to understand how different motives for social TV viewing predict different choices of communication technology platforms. Also, considering social TV viewing involves interactions with others connected via communication technologies, the present study examines the role of social presence to further understand the underlying mechanism of social TV enjoyment.

2. Literature review

2.1. Media use during the COVID-19 lockdown and social TV viewing

Per the CDC's [11] survey during the COVID-19 pandemic, 40% of respondents reported struggling with mental health or substance use, with 31% reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression, and 26% reporting stress or trauma-related disorder symptoms. To address these issues, scholars began to extrapolate and better contextualize these social isolation concerns. Kilgore et al. [12] surveyed U.S. adults during the third week of the public shelter-in-place guidelines (i.e., lockdown) and found that 43% of respondents scored above the standard loneliness cutoff, which is an indication of a strong association with depression and suicidal ideation. Kilgore et al. [12] conclude that loneliness is a critical public health concern and a top priority to consider during social isolation and lockdown orders.

To combat the concerns of social isolation and loneliness associated with COVID-19, many individuals reported adjusting their media consumption to remain engaged and active in a lockdown world. Nearly 37% of TV viewers in the United States reported watching more content since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. Similarly, Dixit et al. [10] found that people are engaged in binge watching more TV content during the pandemic than before. Moreover, a New York Times survey reported that Netflix use, which offers a wide variety of programs including television shows, movies, and documentaries, increased by 16% at the start of the pandemic, while Facebook and YouTube use increased by 27% and 15% respectively [14]. In fact, research reports that watching television can be helpful in mitigating the most detrimental social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, including cultivating a positive atmosphere among those isolated to their homes [15].

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the way people watch TV, particularly during the lockdown. Traditional TV viewing is generally regarded as a social experience, but viewing is limited by proximal space; that is, sharing the social experience is limited only to those present in the same physical room as the television [16]. However, social TV viewing has extended the nature of social experiences to an unlimited audience connected via diverse ranges of communication technologies. With the idea of virtual co-viewing, known in the literature as social TV viewing, what was once a traditionally entertainment-based medium [17] is now experiencing large amounts of social engagement [9,[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]].

While there exists a variety of approaches to defining social TV viewing, the phenomenon generally focuses on the use of to communicate with others while viewing TV [21]. More specifically, social TV viewing refers to the simultaneous act of watching TV content while communicating with others online, deemed virtual co-viewers, about that same content [9]. On account of the lockdown mandates in several parts of the world, social TV viewing behaviors are of particular interest for both this study and the COVID-19 era.

2.2. Uses & gratifications and social TV viewing

The framework of uses and gratifications (U&G) provides a fundamental understanding of why people use media, as well as what gratifications people receive from using the media ([57]; [23]. U&G is an audience-centered approach that considers the audience to be active members in deciding why they use a particular medium. The U&G approach marked a turn for media theories, as people are no longer considered to mindlessly engage with media. Many scholars have used the U&G approach to better understand why individuals use a variety of media, including television (e.g. Ref. [23]), the Internet (e.g. Ref. [24]), and social media (e.g., Ref. [25]). Thus, a U&G approach is useful in understanding how individuals engage in social TV viewing, especially during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Social TV viewing is unique, as it requires the use of two different media, television and communication technology platforms (e.g., social media, message applications), to communicate with others. Thus, motives of TV viewing and Internet use are relevant in the understanding of social TV viewing motives. Early research identifies four important motives that explain why individuals engage in TV viewing, including information-seeking, entertainment, companionship, and social interaction [23]. Similarly, motives for using the Internet include interpersonal utility, passing time, information seeking, convenience, and entertainment [24]. While there exist multiple motives in the literature, those that are consistent across all media platforms may become a basis for motives for social TV viewing.

In general, communication, information, and entertainment are common motives investigated in social TV viewing research [20]. This is evident in other research studies. For example, Doughty et al. [26] found that people engage in social TV viewing because they enjoy communicating with others, and Han and Lee [27] found that people engage in social TV viewing to share and gather information as well as communicate with other likeminded social TV viewers. Additionally, research reports that the social motive is an important motive for social TV viewing [28]. For example, individuals engage in social TV viewing to feel a sense of belongingness, the need for being affiliated to a group, for social purposes [28]; [45].

Research also documents diverse types of communication platforms used by social TV viewers to interact with others. Public platforms are those that are easily and publicly accessible to many people, whereas private platforms are less accessible as they are restricted to a small, targeted group of people [29]. That is, the audience on public platforms is often large and unknown, whereas the audience on private platforms is often limited and targeted [20]. Many public platforms witness masspersonal communication, as they still allow for personal conversations on a public forum, while private platforms often experience more personal or interpersonal communication [29]. Common public platforms include Facebook's News Feed [30] and Twitter's Timeline [31], while common private platforms include text messaging and phone calls [58], as well as message applications such as WhatsApp [20].

In the present study, two types of private platforms are being considered: text-based and video-based private platforms. The study considers that text-based private platforms are communication technologies that primarily afford text-based communication with a targeted audience. These include platforms such as WhatsApp, email, and social media messaging apps [32]. Video-based private platforms are communication technologies that primarily afford video-based communication with a targeted audience or co-viewing of video streaming content through the Internet [33]. Examples of video-based private platforms includes FaceTime, Zoom, and Skype.

Concerning the use of platforms, research indicates that people can be engaged either actively or passively [44]. This is apparent on public platforms, such as Facebook's News Feed and Twitter's Timeline. Individuals can actively respond/comment to others or share or post their own content [34]. Individuals can also engage passively by lurking or scrolling on their own social media [27]. However, for private platforms, it may be difficult to distinguish active and passive engagement as interactions on private platforms are considered transactional communication [18].

Taken together, the present study examines how different motives of social TV viewing predict different uses of platforms for social TV engagement. Based on the extant literature, the following motives and platforms are tested. For motives, the present study focuses on the communication, information, entertainment, and social motives. For platforms, the study examines the usage of public platforms, text-based private platforms, and video-based private platforms. As discussed earlier, while active and passive engagement on private platforms are difficult to distinguish, there is a clear distinction of active and passive engagement on public platforms. In this regard, the present study examines the active and passive use of public platforms separately.

Further, it is likely that one's motives for social TV viewing can influence their subsequent engagement on specific platforms. However, scant information is available on this topic. Although not directly related to social TV motives, extant research findings provide some foundational understanding of the possible associations between social TV motives and the choice of using a particular platform. For example, Leung [35] found that primary motives for using a text-based platform (texting) are entertainment, affection, fashion, escape, convenience and low costs, and coordination, and Buhler et al. [36] found that people use video chatting or video-based platforms for largely social needs. Further, Cha and Chan-Olmsted [33] identified that people use video-based platforms for companionship, social interaction, entertainment, escape, boredom relief, and timely learning. In all, based on the extant literature, the present study takes an exploratory approach to understand how social TV motives are associated with the choice of platforms by raising the following research question.

RQ1

How do different motives of social TV viewing (communication, information, entertainment, social motives) predict the use of different communication technology platforms for social TV engagement (active and passive engagement of public platforms, text-based private platforms, video-based private platforms)?

2.3. Social presence

Regardless of the type of social TV platforms and levels of engagement, social TV viewers engage in a variety of interactions with virtual co-viewers. Virtual co-viewers refer to other social TV viewers that are connected online through the Internet [22]. In understanding social TV viewing with virtual co-viewers, an important question that naturally arises is whether social TV viewing with virtual co-viewers would directly lead to social TV enjoyment. While frequent social TV viewing might directly increase one's enjoyment, the present study argues that there is an important underlying mechanism that explains how and why social TV viewing leads to enjoyment. In particular, the present study predicts that perceived social presence of virtual co-viewers would play an important role that connects social TV viewing and its enjoyment.

Originated from Short et al. [37]; social presence has received much attention from scholars. Although the definition of the notion is not completely agreed upon, social presence is generally understood as a feeling of being connected to others that are physically away [38] without necessarily noticing the existence of media [39]. Simply put, it is a feeling as if someone is around when the person is not physically present.

Due to the complex nature of social presence, research documents multiple aspects of it, such as social presence as psychological involvement and social presence as copresence (e.g., Refs. [38,40]. While both aspects are equally important, social presence as copresence, which is concerned with a feeling of being together with another entity in the same space, seems particularly relevant to the purpose of this investigation considering the restricted physical social contacts during the lockdown.

The extant literature indicates that social presence (or presence, a broader notion of social presence, see Ref. [39], can be facilitated by various factors, such as technology-related factors, user factors, and social factors [41,42]. Due to the technological factors, when users engage in social TV viewing, the degree of social presence experienced on a public platform and private platform might differ. Even on the same platform, particularly public platforms, users may feel different levels of social presence when posting comments on someone's social media (e.g., active engagement) as compared to reading postings without leaving any comment (e.g., passive engagement). Thus, it is possible that depending on the communication technology platforms (e.g., public, private, text-based, video-based) and level of engagement (active vs. passive), users would feel different levels of social presence.

Given that the nature of social TV viewing can create a feeling of virtual togetherness [43], extant research highlights the importance of social presence in social TV viewing experiences. Lin and Chiang [43] examined how social factors such as social presence affect social TV viewing experiences. The study found that social presence is positively associated with bridging social capital among social TV viewers and TV program commitment, which naturally lead to program loyalty. Related work [44] also reports that social presence is a crucial factor for adoption of social TV systems (e.g., multiscreen social TV systems). Given that social TV viewing provides a communal viewing experience [45], the extant body of literature highlights social presence as an important factor for an enjoyable social TV viewing experience [20,46].

Noting the nature of social presence, the present study argues that social presence would function as a mediator between social TV viewing and social TV enjoyment. In a typical media experience, media use and enjoyment can have direct associations with each other. However, this might not always be true in social TV viewing. Considering that an important part of social TV viewing experiences includes interacting with virtual co-viewers, the study argues that social TV viewers’ perceptions about virtual co-viewers would play a mediating role. More specifically, the study predicts that frequent social TV engagement, which is automatically related to frequent interactions with virtual co-viewers, leads to a greater social presence of virtual co-viewers, and the greater social presence fosters social TV enjoyment. In other words, social presence is the reason why social TV engagement ultimately leads to enjoyment.

In fact, this mediating role of social presence is well documented in social TV viewing literature (e.g., Refs. [9,19,22]. However, the scope of the extant literature is somewhat limited to social TV engagement on communication technology platforms in general for social TV engagement, rather than distinguishing each type of platform. Also, research examining the mediating role of social presence regarding the usage of video-based private platforms is limited. Thus, the present investigation aims to fill this gap. Based on extant literature, the present research proposes the mediating role of social presence on multiple types of platforms as following.

H1

Social presence of virtual co-viewers mediates the relationship between social TV engagement on communication technology platforms (active use of public platforms, passive use of public social media platform, text-based private platforms, video-based private platforms) and social TV enjoyment.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Initially, a total of 367 undergraduate students responded to the study from multiple universities located in the states of Pennsylvania, New York, Missouri, California, Washington, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Ohio in the United States. To identify eligible participants and to ensure the quality of the data, a series of screening questions were asked. First, questions were asked to identify social TV viewers. To be consistent with the conceptual definition of social TV viewing discussed earlier, the following filter questions were asked for public platforms, text-based private platform, and video-based private platforms, respectively, prior to asking about social TV viewing-related questions: “While watching TV during the past two weeks, did you check your [communication technology platforms (e.g., Twitter Timeline or Facebook News Feed; text messaging apps; video chatting platforms)] at least once, to communicate with others about the TV program that you were watching?” As a result, 196 individuals were not eligible for the study and therefore were eliminated from the dataset.

Second, to ensure the quality of the data, two other steps were taken. Considering that some participants may have completed the survey more than once, the study identified and eliminated second-time responses. Also, an attention check was assessed in the middle of the survey to ensure that participants read the survey questions accurately and attentively. In particular, the following question was posed in the middle of the survey to filter out inattentive responses: “Please click 2 in order to move to the next page.” After these two steps, 17 responses were eliminated. Lastly, for the purpose of the study, individuals who reported not practicing social distancing during the past two weeks prior to completing the survey questionnaire were eliminated from the dataset. To clarify, social distancing was described as following: “According to the CDC, social distancing, also called physical distancing, means keeping space between yourself and other people outside of your home, including no gathering in groups.” As a result, 13 responses were eliminated.

After the series of data cleaning processes, the final sample consisted of 141 social TV viewers, who practiced social distancing during the lockdown. The sample included more females (n = 93; 66%) than males (n = 45; 31.9%). Three individuals (2.1%) did not disclose their biological sex. The average age was 22.57 (SD = 5.62), and most of the participants were Caucasian/White (n = 88; 62.4%), followed by Latino/a/x or Hispanic (n = 21; 14.9%), Asian (n = 15; 10.6%), Black/African American (n = 12; 8.5%), and other racial and ethnic groups (n = 5; 3.5%).

3.2. Procedure

The primary researcher contacted several instructors at multiple universities in the United States and received permission to recruit participants from their classes. Upon the university's IRB approval, a recruitment message was distributed to several undergraduate classes through the course instructors. Interested individuals were asked to visit the research participation website to take the survey. A survey questionnaire was distributed via a university-licensed online survey tool (www.qualtrics.com).

Before beginning the survey, participants were asked to read and acknowledge the informed consent. Then, a series of questions were asked to identify eligible participants for the study, as described in the participant section. Eligible individuals (social TV viewers) were proceeded to take the survey, while non-eligible individuals were redirected to a set of questions that are not associated with the present research. At the end of the survey, participants were asked whether they practiced social distancing during the past two weeks.

Because the goal of the study was to understand social TV viewing during the lockdown, the data collection occurred near the end of April 2020 when the lockdown was reinforced. All survey respondents received extra credit for their participation. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed.

3.3. Measures

The survey included a set of measures for social TV viewing experiences. First, four motives of social TV viewing were measured to assess why participants engaged in social TV viewing during the lockdown. The communication motive (α = 0.85) was measured with seven items (e.g., “Because I want to engage in the conversation about the program” and “Because I can express my thoughts about the program”). The information motive (α = 0.81) was measured with six items (e.g., “Because I can answer others’ questions about the program” and “Because I can learn some useful information about the program”). The entertainment motive (α = 0.74) was assessed with four items (e.g., “I want to see witty, humorous expressions about the program” and “Because it is fun and enjoyable in itself”). Items for the communication, information, and entertainment motives were adopted from previous research [47]. The social motive (α = 0.90) was measured with five items. Two items were adopted from McDonald et al. [48] (e.g., “Because it gives me a chance to spend time with others”) and three items were developed for this study (“Because it provides me with needed social interaction with others,” “Because it helps with building my social relations with others,” and “Because it satisfies my social needs”). Responses for all motives-related items were obtained on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree).

Social TV engagement evaluated the frequency of social TV viewing, and it was assessed in four different ways. Regarding public platforms, the present investigation focused on the public aspects of two particular social media sites: Facebook's News Feed and Twitter's Timeline. Specific instructions were provided to participants that their responses should be based on their uses of these two particular platforms. Active social TV engagement on a public platform (α = 0.78) was measured with four items (e.g., “Posting TV program-related information on a personal social media page” and “Commenting on the TV program related posting”). Passive social TV engagement on a public platform (α = 0.89) was evaluated with three items (e.g., “Seeing people's comments on TV program-related issues” and “Seeing a TV program-related article, video, or photo”). Measures for both active and passive social TV engagement on a public platform were adopted from Lin (2016) with a 5-point response option (1 = Never; 5 = Very Frequently).

Social TV viewing on private platforms were measured somewhat differently considering the nature of the platforms. Social TV engagement on a text-based platform was measured with the summed score of the following items: talking about the TV program via (1) text-based messaging (e.g., WhatsApp, traditional text), (2) “private” messages/chat on social media (Facebook messages), and (3) other types of text messaging app. Social TV engagement on a video-based platform was measured with the summed score of the following items: talking about the TV program via (1) Netflix party, (2) Skype/Zoom/FaceTime, and (3) other types of video chatting platforms. Responses for each was measured on a 5-point scale (1 = Never; 5 = Very Frequently).

Social presence (α = 0.81) evaluated participants’ perceptions about virtual co-viewers. It was measured with five items, adopted from Nowak and Biocca [49] (e.g., “I felt like as if they were in the same room” and “I felt like they were watching the game together”). Social TV enjoyment (α = 0.93) assessed how much they enjoyed communicating with virtual co-viewers online. It was measured with six items (e.g., “enjoyable” and “fun”) adopted from Tamborini et al. [50]. Responses for both social presence and social TV enjoyment were obtained on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree). See Table 1 for descriptive statistics of the variables. A complete set of survey questions is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for each variable (N = 141).

| Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Communication motive | 4.56 | 1.18 |

| Information motive | 4.44 | 1.09 |

| Entertainment motive | 5.13 | 1.16 |

| Social motive | 4.55 | 1.33 |

| Social presence | 4.26 | 1.15 |

| Social TV enjoyment | 5.09 | 1.11 |

| Active social TV engagement on public platforms | 2.51 | 0.91 |

| Passive social TV engagement on public platforms | 4.52 | 1.41 |

| Social TV engagement on video-based platforms | 6.98 | 3.24 |

| Social TV engagement on text-based platforms | 8.92 | 3.25 |

Note. Responses for all four motives (communication, information, entertainment, social), social presence, and social TV enjoyment were obtained on a 7-point Likert-type scale, and scores are the average of the summed scores. Responses for active and passive social TV engagement on public platforms were obtained on a 5-point scale, and scores are the average of the summed scores. Finally, social TV engagement on text-based and video-based platforms were obtained on a 5-point scale, and scores are the summed scores, which could vary between 3 and 15 (3 items for each variable).

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: Social TV motives and social TV platforms

RQ1 explored how social TV motives lead to different uses of platforms for social TV engagement. To answer RQ1, a series of multiple regressions were performed for each type of platform.

4.1.1. Active use of public platforms

The results of the multiple linear regression analysis indicated that the four motives explained 19% of the total variance (R 2 = 0.19, F (4, 136) = 8.09, p < .001). More specifically, the information motive significantly predicted active use of public platforms (β = 0.32, p < .01). However, the communication motive (β = 0.08, p > .05), entertainment motive (β = - 0.03, p > .05), and social motive (β = 0.16, p > .05) were not statistically significant.

4.1.2. Passive use of public platforms

The results indicated that the four motives explained 33% of the total variance (R 2 = 0.33, F (4, 136) = 16.74, p < .001). Specifically, the results indicated that the social motive (β = 0.34, p < .001) and entertainment motive (β = 0.25, p < .05) significantly predicted passive use of public platforms. However, the information motive (β = 0.03, p > .05) and communication motive (β = 0.14, p > .05) were not statistically significant.

4.1.3. Text-based private platforms

The results of the multiple linear regression analysis indicated that the four predictors explained 24% of the total variance (R 2 = 0.24, F (4, 136) = 10.53, p < .001). Specifically, the information motive (β = 0.31, p < .01) and social motive (β = 0.23, p < .05) significantly predicted use of text-based private platforms. However, the communication motive (β = - 0.08, p > .05) and entertainment motive (β = 0.11, p > .05) were not statistically significant.

4.1.4. Video-based private platforms

The results indicated that the four motives explained 23% of the total variance (R 2 = 0.23, F (4, 136) = 10.35, p < .001). Specifically, the social motive significantly predicted use of video-based private platforms (β = 0.49, p < .001). However, the communication motive (β = - 0.09, p > .05), information motive (β = 0.13, p > .05), and entertainment motive (β = - 0.08, p > .05) were not statistically significant. See Table 2 .

Table 2.

Social TV motives and social TV engagement (RQ1).

| Social TV motives (β) | Platforms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active use of public | Passive use of public | Text-based private | Video-based private | |

| Information | .32** | .03 | .31* | .13 |

| Communication | .08 | .14 | -.08 | -.09 |

| Entertainment | -.03 | .25* | .11 | -.08 |

| Social | .16 | .34*** | .23* | .49*** |

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

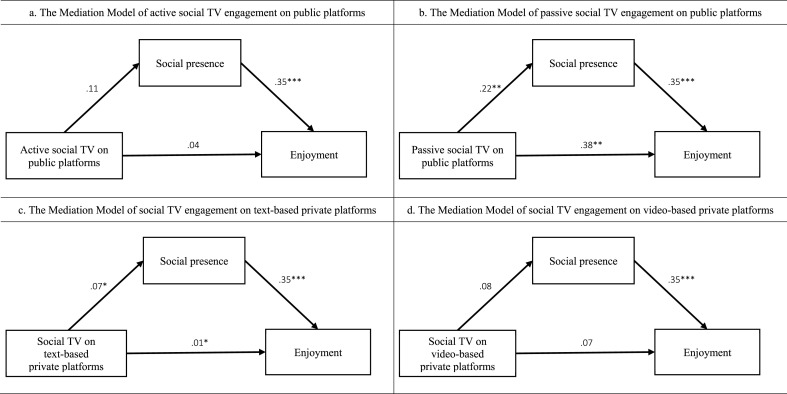

4.2. H1: Mediation effects of social presence

H1 predicted that social presence of virtual co-viewers mediates the relationship between social TV engagement and social TV enjoyment. To test H1, a series of PROCESS analyses (model # 4) were conducted [51]. The procedure was based on 5000 bootstrap samples, and the results were interpreted based on the 95% Confidence Interval (CI). In order to examine the mediation effect of social presence in relation to the unique nature of each platform, social TV engagement via other platforms were controlled for.

4.2.1. Active social TV engagement on public platforms

The results indicated that social presence did not mediate the relationship between active social TV engagement on public platforms and social TV enjoyment (indirect effect = 0.04, Boot SE = 0.04; CI = [- 0.04, 0.12]). While controlling for social TV engagement on other platforms, active social TV engagement on public platforms did not predict social presence (a = 0.11), but social presence positively predicted social TV enjoyment (b = 0.35). The direct effect of active social TV engagement on public platforms on social TV enjoyment was not statistically significant (direct effect = 0.01, Boot SE = 0.10; CI = [- 0.19, 0.20]).

4.2.2. Passive social TV engagement on public platforms

The results indicated that social presence mediated the relationship between passive social TV engagement on a public platform and social TV enjoyment (indirect effect = 0.08, Boot SE = 0.03; CI = [ 0.03, 0.13]). While controlling for social TV engagement on other platforms, passive social TV engagement on public platforms predicted social presence (a = 0.22), which led to greater social TV enjoyment (b = 0.35). Additionally, the direct effect of passive social TV engagement on public platforms on social TV enjoyment remained statistically significant (direct effect = 0.30, Boot SE = 0.06; CI = [0.19, 0.42]).

4.2.3. Social TV engagement on text-based private platforms

The results indicated that social presence mediated the relationship between social TV engagement on text-based private platforms and social TV enjoyment (indirect effect = 0.03, Boot SE = 0.01; CI = [ 0.003, 0.06]). While controlling for social TV engagement on other platforms, social TV engagement on text-based private platforms predicted social presence (a = 0.08), which led to greater social TV enjoyment (b = 0.35). When social presence was considered, the direct effect of social TV engagement on text-based private platforms on social TV enjoyment was not statistically significant (direct effect = 0.04, Boot SE = 0.03; CI = [- 0.01, 0.10]).

4.2.4. Social TV engagement on video-based private platforms

The results indicated that social presence mediated the relationship between social TV engagement on video-based private platforms and social TV enjoyment (indirect effect = 0.02, Boot SE = 0.01; CI = [ 0.002, 0.03]). While controlling for social TV engagement on other platforms, social TV engagement on video-based private platforms predicted social presence (a = 0.07), which led to greater social TV enjoyment (b = 0.35). When social presence was considered, the direct effect of social TV engagement on video-based private platforms on social TV enjoyment was not statistically significant (direct effect = - 0.02, Boot SE = 0.03; CI = [- 0.07, 0.03]). See Table 3 and Fig. 1 .

Table 3.

Mediation effects of social presence on social TV enjoyment (H1).

| Social TV Engagement | β | SE | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Active social TV on public platforms | ||||

| Total Effect | .04 | .10 | -.16 | .25 |

| Direct Effect | .01 | .10 | -.19 | .20 |

| Indirect Effect | .04* | .04 | -.04 | .12 |

| Passive social TV on public platforms | ||||

| Total Effect | .38*** | .06 | .26 | .50 |

| Direct Effect | .30*** | .06 | .19 | .42 |

| Indirect Effect | .08* | .03 | .03 | .13 |

| Social TV on text-based private platforms | ||||

| Total Effect | .07* | .03 | .01 | .13 |

| Direct Effect | .04 | .03 | -.01 | .10 |

| Indirect Effect | .03* | .01 | .00 | .06 |

| Social TV on video-based private platforms | ||||

| Total Effect | .01 | .03 | -.05 | .06 |

| Direct Effect | -.02 | .03 | -.07 | .03 |

| Indirect Effect | .02* | .01 | .00 | .05 |

Note. Social TV refers to social TV engagement.

ULCI: Upper-level confidence interval, LLCI: Lower-level confidence interval.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Fig. 1.

a-d:The Mediation Model of Social Presence on Social TV Enjoyment (H1). a. The Mediation Model of active social TV engagement on public platforms. b. The Mediation Model of passive social TV engagement on public platforms. c. The Mediation Model of social TV engagement on text-based private platforms. d. The Mediation Model of social TV engagement on video-based private platforms. Note. Social TV refers to social TV engagement. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

5. Discussion

5.1. Primary findings and implications for social TV research

The present research examines social TV viewing during the COVID-19 lockdown among college students in the U.S. and reveals important findings and implications for social TV research. First, the study finds that different motives are associated with using different platforms for social TV engagement. Notably, the social motive was a significant predictor of three different types of social TV engagement, passive use of public platforms, text-based private platforms, and video-based private platforms. The social motive is also the only motive that is significantly associated with use of video-based private platforms for social TV engagement. While individuals may receive other needs from social TV engagement on various platforms, it is evident that video-based platforms fulfill social needs. This finding is aligned with previous research regarding the use of video-based platforms [36]. Considering that face-to-face social interactions were restricted during the lockdown, this finding makes sense.

The present study also finds that the entertainment motive is only associated with passive engagement on public platforms. This finding might be partially because of the basic nature of television that is traditionally considered a medium for entertainment [17,52], which is also supported in social TV research [26]. It might also be related to the nature of the sample in this investigation. Due to COVID-19, many college students had to leave campus and return home, and this naturally restricted opportunities to visit local bars or gather with college friends. Thus, to compensate for the entertainment they are lacking in their social lives during the lockdown, the college students may have turned to social TV viewing to meet their entertainment needs. In particular, by browsing through what other people are talking about or sharing on public platforms about the TV program they are watching, which is a similar act of people watching or listening to friends in face-to-face social gatherings, they may have sought to meet entertainment needs through this media use. In fact, this finding is aligned with Kim et al.’s [18] research that the entertainment motive is the strongest predictor of passive social TV engagement.

Further, the information motive predicts active use on public platforms and text-based private platforms. This finding is aligned with previous research that demonstrates individuals may text others for information when engaging in social TV viewing on a private platform [20], or they may actively ask questions to a larger audience on a public platform [34]. Thus, social TV viewers use an active strategy for information seeking or sharing by interacting with a large audience on public platforms as well as a targeted audience on private platforms. In fact, a similar pattern of social TV engagement on private platforms is found in Kim et al.’s [18] research.

Overall, the findings contribute to our understanding of how individuals use and engage with media content via social TV viewing when they are proximally isolated from their social groups. Perhaps, absent social gatherings and opportunities to engage proximally with social circles, individuals may have been both drawn to media and drawn to engaging with others with certain motives for specific communication platforms. This tendency is clear in the present study, as the social motive significantly predicts various types of social TV engagement. Social TV viewing allows individuals to not only stay socially engaged with others, but it also allows individuals to consume television content with others, just as they may have when social contacts were not restricted. In this regard, the present study provides important implications and understanding for intended media use when social contacts are restricted.

Collectively, the present study contributes to expanding social TV research. Though research investigates social TV viewing experiences from diverse perspectives, relatively limited information is available regarding different patterns of social TV viewing experiences on different types of communication technology platforms (e.g., public vs. private; text-based; video-based) and with varying degrees of engagement on public platforms (active vs. passive). In particular, while communication platforms that allow for video cues have been around for some time (e.g., Skype, FaceTime, Zoom), others, such as Teleparty (formerly known as Netflix Party), which began in 2020, has only been around for a short amount of time. With limited physical social gatherings due to COVID-19 and new ways of engaging in social TV viewing such as Teleparty, there is a need for more research regarding this media use behavior. Thus, this exploratory study provides preliminary but meaningful findings for future work in this area.

5.2. Primary findings and implications for social presence

The present research also reveals important findings and implications for social presence research. In particular, the study finds that social presence functions as an important mediator between social TV engagement and social TV enjoyment across different platforms. In particular, social TV engagement on passive use of public platforms, text-based private platforms, and video-based private platforms positively lead to perceived social presence of virtual co-viewers, which naturally fosters social TV enjoyment. In fact, the mediating role of social presence has been highlighted in diverse contexts of social TV research (e.g., Refs. [9,19,22].

What is particularly unique and important in this investigation is that the role of social presence could vary depending on the type of platform. As reported earlier, this study finds different patterns of results between public and private platforms. Regarding public platforms, the direct effect of the passive use of social TV engagement on enjoyment still remains even after considering the role of social presence. This means passive social TV engagement on public platforms has a unique contribution to social TV enjoyment, regardless of social presence of virtual co-viewers. That is, passively engaging on social TV viewing itself (e.g., browsing) could lead to enjoyment. However, for private platforms, the direct effects of both text-based and video-based platforms on enjoyment become insignificant when social presence is considered. In other words, the reason why social TV engagement on private platforms leads to enjoyment is because of the feeling of social presence of virtual co-viewers. This finding implies that the role of virtual co-viewers is more vital for viewers’ enjoyment on private platforms. Partially, it might be due to the nature of the audience, virtual co-viewers. While the audience is not particularly targeted or identified on public platforms, the audience is specific and targeted on private platforms [20]. Thus, when social TV viewers actively select their own virtual co-viewers on private platforms, they may naturally put more emphasis on their virtual co-viewers.

While statistically significant findings tend to receive more attention, it is also important to address nonsignificant results. Unlike the passive use of public platforms, the present study did not find a significant role of social presence on the active use of public platforms. One possible explanation for this would be the nature and purpose of the messages being communicated on public platforms. When people passively engage in social TV viewing (e.g., browsing and reading others’ comments), social TV viewers may automatically think about the virtual co-viewers who posted such comments or photos. Although it may occur unconsciously, thinking about the sender of the message may naturally enhance the role of virtual co-viewers in the media use experiences. However, when people actively engage in social TV viewing (e.g., posting their own comments or sharing photos), the message focus is on themselves rather than virtual co-viewers. Also, they may not have a specific audience in mind when they share postings. For these reasons, the effect of virtual co-viewers might be limited when engaging in active social TV viewing on public platforms.

Overall, the present research contributes to advancing our understanding of social presence in social TV research. Considering that social presence is one of the important factors for positive mediated experiences [38], a good volume of research documents the important roles of social presence in social TV research (e.g., Refs. [9,18,22]. However, little is known about the role of social presence across different uses and platforms. Considering the nature or characteristics of virtual co-viewers in public and private platforms, it might be reasonable to assume some differences across different patterns of social TV engagement. However, this has not been fully addressed in the extant body of literature. In this regard, the present study contributes to advancing our understanding of the important role of social presence in social TV viewing.

5.3. Limitations and future research directions

Although the present research provides unique and important findings, as with other study, there are limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample only included college students. College students are a relevant and important sample, in large part because of their academic and social lives that were heavily affected by the lockdown [53]. Students are generally attending class with others, living in dorms or campus apartments with peers, and spending a great deal of time on campus, where they are engaged in either social or academic activities. Thus, while everyone was affected by the COVID-19 lockdown, college students were particularly affected, as many were asked to leave campus and return home. This affected their social lives, which is typically considered important for this age group [56]. In that regard, this study provides meaningful information about social TV viewing in this unique group of people. However, the results may not hold for other groups because different demographics may have different motives for media use. For example, parents with young children would have distinctly different media use motives than college students do. In order to have a more general understanding, more research is needed.

Second, the data did not clarify whether participants were living on their own or with others (e.g., family members) during the lockdown. This may raise caution, as the lack of this information could be perceived as a limitation. However, whether participants lived on their own or with others, everyone's social life outside the house was restricted as they reported in the screening question regarding social-distancing practices. Thus, the study's findings are still meaningful in this data set. Though, to be conservative in making an argument, this limitation should be considered.

Third, the present study did not account for different media program types. Social TV viewing behaviors and motives might be different when accounting for different genres of media content, such as the differences between reality TV (e.g., Love is Blind) or documentary TV (e.g., Tiger King). In fact, Ebersole and Woods [54] found that reality television viewing is ritualized more than other genres and is primarily motivated by identification with characters and vicarious participation. Conversely, Pittman and Sheehan [55] found that Netflix viewers, particularly those that binge watch content, value engagement, relaxation, hedonism, and aesthetics. Taken together, the uses and gratifications for media use differ depending on the genre viewed. In this regard, future researchers are encouraged to further investigate social TV viewing behaviors and motives across various genres of TV programming

Lastly, although the present study's finding demonstrates social TV viewing behavior during the lockdown, it does not explain how it is different compared to when people's social lives are not restricted. In this regard, the present study encourages future researchers to conduct a longitudinal study and examine how people's social TV viewing behavior changes over various events that may hinder people's social life activities. Considering that such regulations like a lockdown order is not usually planned far in advance or predicted, comparing media use behavior during and after such regulation would provide a more concrete idea about how people tune into and use media when their physical get-togethers and social life are restricted.

5.4. Conclusion

The present study sought to understand social TV viewing behaviors during the COVID-19 lockdown. Findings suggest that different social TV motives predict different uses of platforms for social TV engagement, such as public platforms, text-based private platforms, and video-based private platforms. Specifically, the social motive significantly predicts social TV engagement on most of the platforms. The study also highlights a mediating role of social presence of virtual co-viewers in social TV enjoyment. In particular, the role of social presence appears to be specifically important on private platforms. Collectively, the study provides meaningful understanding of how people engage in social TV viewing when social gatherings are restricted.

Author statement

Jihyun Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision. Kelly Merrill Jr.: Resources, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Chad Collins: Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Hocheol Yang: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – Original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Biographies

Jihyun Kim (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) is an Associate Professor in the Nicholson School of Communication and Media at the University of Central Florida in the U.S.

Kelly Merrill Jr. (M.A., University of Central Florida) is a doctoral student in the School of Communication at the Ohio State University in the U.S.

Chad Collins (M.A., University of Central Florida) is an independent researcher.

Hocheol Yang (Ph.D., Temple University) is an Assistant Professor in the Graphic Communication Department at the California Polytechnic State University.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Social Isolation and Loneliness: the Silent Pandemic.https://www.myharrisregional.com/news/social-isolation-and-loneliness-the-silent-pandemic Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda K., Snower D. How COVID-19 changed the world: G-7 evidence on a recalibrated relationship between market, state, and society. 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-covid-19-changed-the-world-g7-evidence-on-a-recalibrated-relationship-between-market-state-and-society/ Retrieved from.

- 3.Saladino V., Algeri D., Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. 577684–577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tebor O. Delta variant causes new lockdowns and coronavirus restrictions across the globe. 2021. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-07-01/delta-variant-worldwide-coronavirus-restrictions Retrieved from.

- 5.Clair R., Gordon M., Kroon M., Reilly C. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2021;8(1):1–6. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaya T. The changes in the effects of social media use of Cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020;63:101380. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammed A., Ferraris A. Factors influencing user participation in social media: evidence from twitter usage during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Technol. Soc. 2021;66:101651. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samet A. 2020, June. 2020 US Social Media Usage: How the Coronavirus Is Changing Consumer Behavior.https://www.businessinsider.com/2020-us-social-media-usage-report Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J., Song H., Lee S. Extrovert and lonely individuals' social TV viewing experiences: a mediating and moderating role of social presence. Mass Commun. Soc. 2018;21(1):50–70. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2017.1350715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixit A., Marthoenis M., Arafat S.M.Y., Sharma P., Kar S.K. Binge watching behavior during COVID 19 pandemic: a cross-sectional, cross-national online survey. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;289:113089. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019: COVID-19.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilgore W., Cloonan S., Taylor E., Dailey N. Loneliness: a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marketing Charts . 2021. People Still Say They’re Watching More TV than They Did Pre-pandemic.https://www.marketingcharts.com/digital/video-115773 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koeze E., Popper N. 2020, April. The Virus Changed the Internet.https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayedee N., Manocha S. Role of media (television) in creating positive atmosphere in COVID 19 during lockdown in India. Asian Journal of Management. 2020;11(4):370–378. doi: 10.5958/2321-5763.2020.00057.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harboe G. In: Social Interactive Television: Immersive Shared Experiences and Perspectives. Cesar D. Geerts, Chorianopoulos K., editors. IGI Global; Hershey, PA: 2009. In search of social television; pp. 1–13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gitlin T. Prime time ideology: the hegemonic process in television entertainment. Soc. Probl. 1979;26(3):251–266. doi: 10.2307/800451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J., Merrill K., Jr., Yang H. Why we make the choices we do: social TV viewing experiences and the mediating role of social presence. Telematics Inf. 2019:101281. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J., Merrill K., Jr., Collins C. Touchdown together: social TV viewing and social presence in a physical co-viewing context. Soc. Sci. J. 2020 doi: 10.1080/03623319.2020.1833149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krämer N.C., Winter S., Benninghoff B., Gallus C. How “social” is Social TV? The influence of social motives and expected outcomes on the usage of Social TV applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;51:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raney A., Ji Q. Entertaining each other? Hum. Commun. Res. 2017;43(4):424–435. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song H., Kim J., Choi Y. The role of social presence in social TV viewing. Journal of Digital Contents Society. 2019;20(8):1543–2553. doi: 10.9728/dcs.2019.20.8.1543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin A.M. Television uses and gratifications: the interactions of viewing patterns and motivations. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 1983;27(1):37–51. doi: 10.1080/08838158309386471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papacharissi Z., Rubin A.M. Predictors of internet use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 2000;44(2):175–196. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4402_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiting A., Williams D. Why people use social media: a uses and gratifications approach. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2013;16(4):362–369. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2013-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doughty M., Rowland D., Lawson S. Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Interactive TV and Video. 2012. Who is on your sofa?: TV audience communities and second screening social networks; pp. 79–86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han E., Lee S.W. Motivations for the complementary use of text-based media during linear TV viewing: an exploratory study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;32:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Highfield T., Harrington S., Bruns A. Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013;16(3):315–339. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.756053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Sullivan P.B., Carr C.T. Masspersonal communication: a model bridging the mass-interpersonal divide. New Media Soc. 2018;20(3):1161–1180. doi: 10.1177/1461444816686104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burkell J., Fortier A., Wong L.L.Y.C., Simpson J.L. Facebook: public space, or private space? Inf. Commun. Soc. 2014;17(8):974–985. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.870591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak H., Lee C., Park H., Moon S. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web. 2010. April). What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park N., Chung J.E., Lee S. Explaining the use of text-based communication media: an examination of three theories of media use. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012;15(7):357–363. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cha J., Chan-Olmsted S.M. Substitutability between online video platforms and television. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2012;89(2):261–278. doi: 10.1177/1077699012439035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panek E.T., Nardis Y., et al. Mirror or megaphone?: how relationships between narcissism and social networking site use differ on Facebook and Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(5):2004–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung L. Unwillingness-to-communicate and college students' motives in SMS mobile messaging. Telematics Inf. 2007;24(2):115–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2006.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhler T., Neustaedter C., Hillman S. Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 2013, February. How and why teenagers use video chat; pp. 759–768. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Short J., Williams E., Christie B. John Wiley & Sons; NY: 1976. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biocca F., Harms C., Burgoon J.K. Toward a more robust theory and measure of social presence: Review and suggested criteria. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2003;12(5):456–480. doi: 10.1162/105474603322761270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee K.M. Presence, explicated. Commun. Theor. 2004;14(1):27–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00302.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly S.E., Westerman D.K. In: Handbook of Communication and Learning, 16: Communication and Learning. Witt P.L., editor. De Gruyter; 2016. New technologies and distributed learning systems. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee K.M., Nass C. Social-psychological origins of feelings of presence: creating social presence with machine-generated voices. Media Psychol. 2005;7:31–45. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0701_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lombard M., Ditton T. At the heart of it all: the concept of presence. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 1997;3(2) doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin T.T., Chiang Y.H. Bridging social capital matters to social TV viewing: investigating the impact of social constructs on program loyalty. Telematics Inf. 2019;43:101236. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin T.T. Multiscreen social TV system: a mixed method understanding of users' attitudes and adoption intention. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019;35(2):99–108. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2018.1436115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wohn D.Y., Na E.K. Tweeting about TV: sharing television viewing experiences via social media message streams. Clin. Hemorheol. and Microcirc. 2011;16(3) doi: 10.5210/fm.v16i3.3368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen E.L., Lancaster A.L. Individual differences in in-person and social media television coviewing: the role of emotional contagion, need to belong, and coviewing orientation. Cyberpsychol., Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014;17:512–518. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko M., Choi S., Lee J., Lee U., Segev A. Understanding mass interactions in online sports viewing: chatting motives and usage patterns. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2016;23(1):6. doi: 10.1145/2843941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald M.A., Milne G.R., Hong J. Motivational factors for evaluating sport spectator and participant markets. Sport Market. Q. 2002;11(2):100–113. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowak K.L., Biocca F. The effect of the agency and anthropomorphism on users' sense of telepresence, copresence, and social presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2003;12(5):481–494. doi: 10.1162/105474603322761289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamborini R., Bowman N.D., Eden A., Grizzard M., Organ A. Defining media enjoyment as the satisfaction of intrinsic needs. J. Commun. 2010;60(4):758–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01513.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayes A.F. 2nd. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galetić F., Dabić M. Quo Vadis public television? Market position of selected Western European countries. Technol. Soc. 2021;66:101634. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alam G.M. Does online technology provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh—a comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol. Soc. 2021;66:101677. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ebersole S., Woods R. Motivations for viewing reality television: a uses and gratifications analysis. Southwestern Mass Communication Journal. 2007;23(1):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pittman M., Sheehan K. Sprinting a media marathon: uses and gratifications of bulge-watching television through Netflix. Clin. Hemorheol. and Microcirc. 2015;20(10) doi: 10.5210/fm.v20i10.6138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Capraro A.J., Patrick M.L., Wilson M. Attracting college candidates: the impact of perceived social life. J. Market. High Educ. 2004;14(1):93–106. doi: 10.1300/J050v14n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz E., Gurevitch M., Haas H. On the use of mass media for important things. Am. Socio. Rev. 1973;38:164–181. doi: 10.2307/2094393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vermeulen A., Vandebosch H., Heirman W. Shall I call, text, post it online or just tell it face-to-face? How and why Flemish adolescents choose to share their emotions on-or offline. J. Child. Media. 2018;12(1):81–97. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2017.1386580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]