Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly changed how consumers live. This research investigated the impact of the pandemic on two important life goals—material versus relational goals—as well as their subsequent consequences on consumer subjective well-being (SWB). We conducted a three-wave longitudinal study and recruited 1567 participants from mainland China during the pandemic. Cross-lagged model results showed that consumers’ perceived threat of the pandemic was positively related to the importance placed on material and relational goals, which conduced to divergent effects on consumer SWB. Specifically, the greater the threat consumers perceived in the pandemic, the more emphasis they placed on material success and social relationships. However, pursuing material goals had a negative impact on SWB, but relational goals had a favorable influence on SWB. Our findings enhance understanding of how consumers’ life goals changed during the COVID-19 pandemic and offer insights for marketing in the current and future pandemics.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Perceived threat, Material goal, Relational goal, Subjective well-being

1. Introduction

Humans have dealt with infectious diseases for millennia. Major pandemics that have occurred include cholera, bubonic plague, smallpox, the black death, and influenza. Although recent outbreaks—such as SARS, H1N1 influenza, and Ebola—likely remain vivid in people’s memory, the global COVID-19 pandemic (hereafter referred to as “the pandemic” for brevity) has dramatically impacted consumers’ present-day lives. For instance, many national governments invoked lockdowns that inimically affected the global economy and placed consumers under financial strain. Moreover, stay-at-home and physical distancing orders posed a threat to consumers’ need for relationships and social interactions (Campbell et al., 2020). Such economic and relational perils have induced serious mental health problems among millions of people worldwide (WHO, 2020). Therefore, examining how the current pandemic has affected consumers’ life goals and welfare over time is imperative.

This research investigated the impact of the pandemic on consumers’ material and relational life goals and their subsequent consequences on consumers’ subjective well-being (SWB). We propose that the pandemic-induced economic and social distancing, along with the accompanying sense of ontological insecurity, have led consumers to place increased importance on material and relational goals. However, pursuing these two life goals would have divergent impacts on their subjective well-being. Specifically, emphasizing material goals should decrease consumer subjective well-being, but relational goals should augment consumer SWB during the pandemic. These hypotheses were supported by a three-wave longitudinal study among a large Chinese sample during the pandemic.

Our research contributes to the literature in three ways. First, although abundant research has examined the impacts of the pandemic from different perspectives, its influence on consumers’ value orientations and life goals have been largely ignored. Our work thus adds to this stream of literature by investigating the effect of the perceived threat of the pandemic on the importance individuals placed on material and relational goals. Second, though some recent work has focused on the detrimental effect of the pandemic on the well-being of the general public (e.g., Brodeur et al., 2020, Prime et al., 2020, Sibley et al., 2020), no empiricism has considered the role that life goal orientations may play in this relationship. Our undertaking investigated the impact of the pandemic threat on consumer well-being via life goals, thus offering a new theoretical perspective for understanding the relationship between the pandemic and consumer well-being. Third, based on a three-wave longitudinal dataset, our findings provide evidence concerning the development of life goals and consumer well-being over time during the pandemic.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

2.1. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact

COVID-19 was first discovered in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province in Central China, in late 2019. This new infectious respiratory disease—caused by a novel virus SARS-CoV-2—has rapidly spread around the world and was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020. Because of its high level of contagion, significant fatality rates (especially in the early stage), and absence (until recently) of vaccines, the pandemic is considered an unprecedented public health crisis (Krishnamurthy, 2020). In response to the pandemic, most countries have implemented various mitigation strategies, such as social distancing, stay-at-home orders, quarantines, restrictions on travel and mass gatherings, and closures of businesses and schools. Although these lockdowns and social isolation policies effectively prevented transmission of the disease, they also posed dramatic economic and social threats to the world community.

The pandemic has caused an unprecedented shrinkage in the global economy (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Government efforts directed at the pandemic have devasted some industries, such as tourism, hospitality, transportation, and restaurants. Production and supply chains were also significantly disrupted by the pandemic. Many companies went bankrupt, as consumers stayed at home (Tucker, 2020). The World Trade Organization (WTO) declared the pandemic to be the largest economic crisis since the 2008–2009 economic collapse (WTO, 2020). In addition, because of the social distancing and stay-at-home mandates, the pandemic has posed dramatic challenges to social relationships and caused such severe mental health problems as loneliness and depression (Brodeur et al., 2021).

2.2. Material and relational life goals

Pursuing material successes and interpersonal relationships are two important goals in a consumer’s life (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). Material goals emphasize the importance of extrinsic rewards, such as wealth and material possessions (Richins & Dawson, 1992). Relational goals, however, center on the desire to establish and maintain connections with family members, friends, and significant others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). These two goals accord with the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic aspirations that Kasser and Ryan proposed (1993). They averred that aspirations for wealth and material goods are extrinsic goals (external to oneself) that are sought as a means to some other end. Conversely, intrinsic goals, such as self-acceptance, affiliation, and community feelings, are congruent with self-actualizing and growth tendencies that are innate to humans.

Material wealth is necessary to satisfy the basic need for existence and physiological security (Maslow, 1954). However, in a modern, industrialized society inundated with consumerism and materialism, pursuit of wealth and material success transcends merely satisfying lower-order physiological needs and pertains to attainment of a desired social status and expression of one’s self-identity (Shrum et al., 2013). Desire for social relationships and belongingness, on the other hand, is a fundamental human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Belongingness has positive effects on emotions and cognitive abilities; its absence is associated with poor health and maladroit social adjustment (for a review, see Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

2.3. Impact of the pandemic on material and relational goals

Given the economic and social impact that the pandemic has caused, we propose that consumers will emphasize both material and relational goals during the pandemic. We build our hypothesis for the effect on material goals using two rationales. First, the outbreak of the pandemic has resulted in a shortage of material supply because many businesses have been forced to close, and people’s economic insecurity has been omnipresent because of increased unemployment (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Feelings of resource scarcity and economic insecurity motivate people to place greater importance on material possessions and pursue material goals (e.g., Ahuvia and Wong, 2002, Chaplin et al., 2014).

Second, the pandemic has not only resulted in consumer economic insecurity and a scarcity mindset, but it also has induced psychological feelings of uncertainty, fear, and anxiety (Campbell et al., 2020). These sentiments have emerged because of the incertitude and unpredictable nature of the pandemic: people know little about the new virus, cannot discern whether and when the pandemic might be controlled, or ascertain whether and when the world will return to normal. According to prior literature, people tend to pursue material possessions as a psychological buffer to cope with such adverse psychological states (Arndt et al., 2004, Chang and Arkin, 2002, Kasser and Sheldon, 2000, Rindfleisch et al., 2009, Sheldon and Kasser, 2008).

Based on the previous discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: The higher the perceived threat of the pandemic, the greater the importance consumers place on material goals.

We further propose that the pandemic would motivate consumers to aspire for relational goals for two reasons. First, lockdowns and social distancing have deprived consumers of much social interaction. Previous findings have found that individuals seek to re-gain social connections and affiliations when feeling a loss of connectedness (e.g., DeWall and Richman, 2011, Mead et al., 2011). As a result, consumers would seek to connect or reconnect with others (regardless of mode). Indeed, during the pandemic, people have found various ways to reconnect with others, such as choosing to shelter with friends or family members, conducting virtual gatherings, and increasing online interactions with distant family and friends (Kirk and Rifkin, 2020, Sheth, 2020).

Second, the pandemic’s gloomy and lonely atmosphere replete with much uncertainty has engendered a general perception of physical and psychological vulnerability. Social relationships are an important buffering resource used to cope with such adverse feelings (Baumeister and Leary, 1995, Zhou and Gao, 2008). Specific to the pandemic, relational resources not only have provided direct informational and behavioral aids, but also offered socioemotional comfort through individuals’ expressing and receiving care and love.

Based on the foregoing disquisition, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: The higher the perceived threat of the pandemic, the greater the importance consumers place on relational goals.

2.4. Impact of material goals and relational goals on consumer SWB

Although the pandemic threat has enhanced individuals’ pursuit of both material and relational goals, we propose that these two life goal orientations have differential impacts subsequently on consumer SWB. Though consumers have opted for material offerings during the pandemic, prior research has shown that material goal orientation has detrimental effects on consumers’ well-being (Belk, 1985, Burroughs and Rindfleisch, 2002, Kasser and Ahuvia, 2002, Kasser and Ryan, 1993). For example, Belk (1985) found that materialism was negatively related with happiness and life satisfaction. These phenomena occurred partly because, due to social comparison processes, material pursuits are endless and exhausting in the long run. Moreover, they transpired because there was a decreasing marginal utility for material possessions, thus the pleasure derived from a material orientation was fleeting. Because of the economic decline and increased unemployment during the pandemic (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020), one’s ability to fulfill the goal for material success has been increasingly difficult, which further reduces SWB. Therefore, we propose that the increased material goal orientation induced by the pandemic will have a negative impact on consumers’ SWB.

H3: The higher the perceived threat of the pandemic, the greater the importance consumers place on material goals, thus leading to a lower SWB.

In contrast, we predict that the increased emphasis placed on relational goals arising from the pandemic will have a positive impact on subsequent SWB. Prior research has shown that people valuing social relationships reported higher life satisfaction (Froh et al., 2007, Mellor et al., 2008), greater happiness and love (Quoidbach et al., 2019), and less frequent experiences of sadness (Oishi et al., 2013), as well as exhibited positive group identity (Spears, 2021) —all of which contributed to a higher SWB (Diener, Oishi, & Tay, 2018). However, although social distancing impedes physical interactions and one’s presence, new technologies (e.g., social media, video chat) help people stay connected. With the aid of these technologies and tools, people would be more likely to satisfy their relational goals by engaging in such activities as virtual parties, happy hours, and cloud clubbing (Kirk & Rifkin, 2020). We thus posit the following hypothesis:

H4: The higher the perceived threat of the pandemic, the greater the importance consumers place on relational goals, thus leading to a higher SWB.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and data collection

A total of 1567 participants (46.20 % female; Mage = 29.33, SDage = 6.00) completed a three-wave longitudinal survey over a period of 3 months (Time 1: early March, Time 2: early April; Time 3: early May). They provided information about their educational background (171 completed high school, 293 completed junior college education, 973 had bachelor’s degrees, and 130 had master’s or doctorate degrees) and yearly salary (434 were less than100k RMB, 708 were 100–200k, 288 were 200–300k, 104 were 300–500k, 33 were more than 500k).

They finished the survey via an online survey platform in China (http://www.credemo.com). After confirming their online consent, participants reported their perceived pandemic threat, material and relational goal orientations, and SWB during the previous month (i.e. February, March, and April). These three time periods represented the development of the pandemic in China: the early transmission period, the outbreak period, and the waning period (see Fig. 1 ; from National Health Commission of the P.R. China).

Fig. 1.

Number of confirmed cases and the time point of measures. Note: T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

3.2. Measures

Participants were informed to recall the general situation about the previous month (i.e., February/March/April). All measures were on a 7-point Likert-scale.

3.2.1. Perceived threat of the pandemic.

Following Slovic’s (1987) risk perception theory, we measured perceived pandemic threat using the following four questions: “To what extent do you worry that you and your family members get infected by COVID-19?” “How likely do you think you and your family members may be infected by COVID-19?” “How much infection threat do you think you and your family members are facing?” “How severe do you think the COVID-19 pandemic is?” (α ranged from 0.68 to 0.82).

3.2.2. Material and relational goals.

Life goals were assessed with the following two questions adapted from Kasser and Ryan (1996): “How important do you think gaining material success is in your life?” “How important do you think maintaining a good relationship with family members and friends is in your life?”.

3.2.3. Subjective well-being.

Our measure of consumer SWB was affect oriented (Bradburn, 1969). Participants reported how happy, lonely, bored, and anxious they were during the previous month (α ranged from 0.80 to 0.85). The last three items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated higher SWB.

4. Analytic strategy

The cross-lagged model, a type of discrete time structural equation model, was used to test our hypotheses. One advantage of this model is its ability to test whether the proposed effects that the independent variables have on the dependent variables were stable and robust over time (i.e., across the three survey waves; Kenny, 1975, Orth et al., 2021).

To test the effects of perceived pandemic threat on material goals (H1) and relational goals (H2), we initially conducted a cross-lagged model (Model 1) with perceived pandemic threat as the independent variable (IV), material goals and relational goals as the two dependent variables (DV) at three time points. The nine observed variables can be connected by nine synchronous correlations at the same time point, six auto regressions between two instances of the same variable over time, and eight general regressions between IV and DVs, and vice versa. The whole model was subjected to the three-wave data in Mplus 7.0 and evaluated by 4 model fitness indexes— χ 2, df, TLI, CFI, and RMSEA (Marsh et al., 2004).

Next, to test H3 and H4, we included SWB in the model and tested the mediation effect for material goals (mediator variable, MV) and relational goals (MV) on the relationships between perceived pandemic threat (IV) and SWB (DV). Similar to Model 1, the twelve observed variables were also connected by synchronous correlations, auto regressions, and general regression in Model 2. The time-lagged effects of pandemic threat on material goals and relational goals was firstly estimated. Moreover, the cross-lagged mediation effect was tested by the bootstrap approach with 5000 resampling (Wu, Carroll, & Chen, 2018).

Additionally, before doing the analysis, we conducted post-hoc statistical tests for common method variance. Harman’s one factor test was used to estimate the percentage of variance accounted for by the common method variance. In this study, we identified 12 factors and found the first factor accounted for 26.64% of the variance among the variables, which satisfied the criterion (50%; Fuller et al., 2015).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive statistics and changes of key variables over time

The descriptive information (means and standard deviations) of all key variables are presented in Table 1 . Throughout the three survey waves, there was a significant downward trend of consumers’ perceived pandemic threat over time (β = -0.31, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001; February: M = 5.76, SD = 0.87; March: M = 5.26, SD = 0.99; April: M = 4.42, SD = 1.30). This finding was consistent with the fact that the pandemic was waning from March 2020 to May 2020 in China (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations for all variables (n = 1567).

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic Threat | 5.76 ± 0.87 | 5.26 ± 0.99 | 4.42 ± 1.30 |

| Material Goal | 5.03 ± 1.42 | 4.96 ± 1.55 | 5.26 ± 1.33 |

| Relational Goal | 6.38 ± 0.82 | 6.35 ± 0.83 | 6.34 ± 0.82 |

| Subjective Well-being | 4.16 ± 1.35 | 4.41 ± 1.33 | 4.85 ± 1.36 |

We also tested changes in consumers’ SWB over time during the pandemic. Our results indicated that there was a significant increasing trend in consumers’ SWB across the three survey waves (β = 0.12, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001), with the lowest level in February (M = 4.16, SD = 1.35), a middle level in March (M = 4.41, SD = 1.33), and the highest level in April (M = 4.85, SD = 1.36).

Similar analyses were performed for material goals and relational goals. Results showed that there was a significant decline trend for material goals (T1: M = 5.03, SD = 1.42, T2: M = 4.96, SD = 1.55, T3: M = 5.26, SD = 1.33; β = −0.04, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001), but relational goals remained high across the three survey waves (T1: M = 6.38, SD = 0.82, T2: M = 6.35, SD = 0.83, T3: M = 6.34, SD = 0.82; β = −0.02, s.e. = 0.02, p = .186).

5.2. Correlation analysis

Correlations between all key variables are shown in Table 2 . Across three survey waves, we consistently found positive correlations between the perceived pandemic threat and two life goals (for material goals: all r’s ≥ 0.09, all p’s < .010; for relational goals: all r’s ≥ 0.07, all p’s < .010). The perceived pandemic threat was negatively correlated with consumers’ SWB at all three time periods (all r’s ≤ -0.06, all p’s < .050). This suggested that the greater threat the pandemic was perceived to be, the lower consumers’ SWB.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients for all variables (n = 1567).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pandemic Threat (T1) | |||||||||||

| 2. Pandemic Threat (T2) | 0.44** | ||||||||||

| 3. Pandemic Threat (T3) | 0.25** | 0.50** | |||||||||

| 4. Material Goal (T1) | 0.12** | 0.20** | 0.12** | ||||||||

| 5. Material Goal (T2) | 0.09** | 0.16** | 0.19** | 0.49** | |||||||

| 6. Material Goal (T3) | 0.13** | 0.20** | 0.17** | 0.44** | 0.48** | ||||||

| 7. Relational Goal (T1) | 0.16** | 0.16** | 0.08** | 0.09** | 0.04 | 0.10** | |||||

| 8. Relational Goal (T2) | 0.20** | 0.18** | 0.08** | 0.06* | 0.10** | 0.15** | 0.42** | ||||

| 9. Relational Goal (T3) | 0.13** | 0.11** | 0.07** | 0.05* | 0.04 | 0.18** | 0.44** | 0.42** | |||

| 10. Subjective Well-Being(T1) | −0.27** | −0.19** | −0.12** | −0.21** | −0.20** | −0.16** | 0.15** | 0.10** | 0.17** | ||

| 11. Subjective Well-Being(T2) | −0.16** | −0.31** | −0.21** | −0.23** | −0.17** | −0.17** | 0.16** | 0.10** | 0.17** | 0.70** | |

| 12. Subjective Well-Being(T3) | −0.06* | −0.23** | −0.38** | −0.20** | −0.25** | −0.21** | 0.17** | 0.18** | 0.26** | 0.58** | 0.63** |

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

Moreover, material goals were negatively correlated with SWB (all r’s ≤ -0.16, all p’s < .010), but relational goals were positively correlated with SWB (all r’s ≥ 0.10, all p’s < .010). The two life goals were positively correlated (all r’s ≥ 0.04, all p’s < .150).

5.3. Effect of perceived pandemic threat on consumer SWB

To explore the effect of the perceived pandemic threat on consumer subjective well-being, we conducted a cross-lagged model with perceived pandemic threat at the three time points as the independent variables and consumer SWB at the three time points as the dependent variables (see Fig. 2 ). The model freely estimated correlation coefficients between the pandemic threat and SWB at same time point. SWB and the pandemic threat at Time t + 1 were regressed on the same variable at Time t, respectively. SWB at Time t + 1 was regressed on pandemic threat at Time t. Similarly, the pandemic threat at Time t + 1 was also regressed on SWB at Time t.

Fig. 2.

Cross-lagged model results on the effect of pandemic threat on consumer SWB. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

The cross-lagged model fit the data well, as reflected in the fit indexes: χ 2 = 36.50, df = 2, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.105. The results showed that pandemic threat at Time 2 significantly predicted SWB at Time 3 (β = -0.04, s.e. = 0.02, p = .034). However, there was a marginally significant positive relationship between perceived pandemic threat at Time 1 and SWB at Time 2 (β = 0.03, s.e. = 0.02, p = .076). We speculate that this positive effect might be because the initial outbreak of the pandemic was during the Chinese Spring Festival (February 2020), when most Chinese people stayed at home with their family and with pay due to the lockdown policy.

Interestingly, we also observed negative relationships between SWB at Time t and perceived pandemic threat at Time t + 1 (T1-T2: β = -0.08, s.e. = 0.02, p = .001; T2-T3: β = -0.05, s.e. = 0.02, p = .025). These results are consistent with prior research which suggests that a negative mentality sensitizes people to negative information (Butler and Mathews, 1987, Mitte, 2007). In the current research context, people who experienced lower SWB were in a negative mentality. Therefore, they were more likely to interpret information about the pandemic in a more negative way, thus perceived greater pandemic threat in time T + 1.

5.4. Effect of perceived pandemic threat on material and relational goals

A cross-lagged model was conducted to test the effect of the perceived pandemic threat on material and relational goals (H1 and H2). In the model (Fig. 3 ), we simultaneously included three variables at three time points. The relationships between two of these variables within same time point were freely estimated. Each variable at Time t + 1 were regressed on the same variable at Time t. Material goals and relational goals at Time t + 1 were regressed on the pandemic threat at Time t. Similarly, the pandemic threat at Time t + 1 was also regressed on material goals and relational goals at Time t.

Fig. 3.

Cross-lagged model results on the effect of pandemic threat on consumer life goals. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

The cross-lagged model fit the data well: χ 2 = 42.69, df = 12, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.040. The results showed that the pandemic threat at Time t positively predicted material goal at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = 0.06, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = 0.08, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001). The results confirmed our H1 that the greater threat that consumers perceived the pandemic to be, the more importance they placed on material goals. Moreover, the findings indicated that the perceived pandemic threat at Time t positively predicted relational goals at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = 0.06, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = 0.07, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001). The results confirmed our H2 that the greater the perceived threat of the pandemic, the higher the importance consumers placed on relational goals.

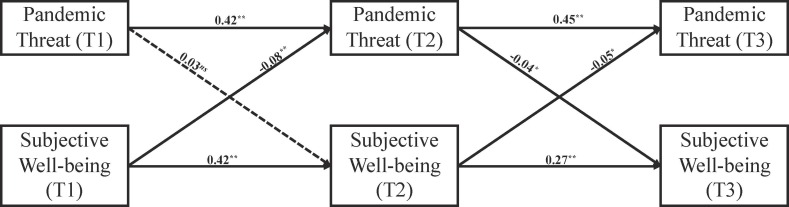

5.5. Mediating effect of material and relational goals

To test H3 and H4 that material and relational goals would further lead to different impacts on consumer SWB, we included SWB in the above model. The model freely estimated all relationships between two of these variables within the same time point. Each variable at Time t + 1 was regressed on the same variable at Time t. In addition to the regression mentioned in the above model, SWB at Time t + 1 was regressed on the pandemic threat, material goals, and relational goals at Time t. Similarly, the pandemic threat, material goals, and relational goals at Time t + 1 were also regressed on SWB at Time t.

As shown in Fig. 4 , the pandemic threat at Time t positively predicted material goals at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = 0.05, s.e. = 0.01, p = .001; T2 → T3: β = 0.06, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001). The material goals at Time t subsequently negatively predicted SWB at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = -0.11, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = -0.12, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001). The mediation model supported the effect of the pandemic threat on SWB through material goals (Effect = -0.01, s.e. = 0.003, p = .002, 95 %CI = [-0.013, −0.003]). This is in line with H3: the higher the pandemic threat, the greater the importance placed on material goals, thus leading to lower SWB.

Fig. 4.

Cross-lagged model results on the mediating role of material and relational goals on the effect of pandemic threat on consumer SWB. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3.

Similarly, the pandemic threat at Time t positively predicted relational goals at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = 0.10, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = 0.12, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001). At Time t it subsequently positively predicted SWB at Time t + 1 (T1 → T2: β = 0.10, s.e. = 0.01, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = 0.10, s.e. = 0.02, p < .001). The mediation model supported the effect of the pandemic threat on SWB through relational goals (Effect = 0.02, s.e. = 0.003, p < .001, 95 %CI = [0.009, 0.022]). Hence, H4 was confirmed: a higher perceived pandemic threat engendered increased importance placed on relational goals, thus leading to higher SWB.

6. Discussion

Given the widespread deleterious influence of COVID-19, examining its psychological consequences is of both theoretical and practical importance. Using a three-wave longitudinal survey during the pandemic in China, this research showed that consumers’ perceptions of the pandemic threat led to increased importance placed on both material and relational goals, which subsequently had divergent impacts on their SWB. Specifically, while material goal orientation had a detrimental impact on individuals’ SWB, relational goal orientation had a favorable influence on their SWB.

6.1. Theoretical contributions

Our findings contribute to the literature in several ways. First, our research contributes to research on the pandemic and disease threat. Although previous work has demonstrated negative psychological impacts associated with COVID-19 and other contagious diseases (e.g., Brodeur et al., 2020, Galoni et al., 2020, Prime et al., 2020, Sibley et al., 2020), what remained unclear was how the pandemic may affect consumers’ life goals. We thus felt that this issue was worthy of investigation because material success and social relationships are the two central life goals among consumers and have substantial impacts on society. Therefore, understanding how individual valuation of these two life goals changes during such health crises as the pandemic offer valuable insights for both business and public policy making.

Second, although some recent studies have suggested that the pandemic has had a negative impact on people’s well-being (e.g., Brodeur et al., 2020, Prime et al., 2020, Sibley et al., 2020), the psychological mechanism underlying this relationship was unclear. In this study, we integrated consumer life goals into the link between perceived pandemic threat to consumer well-being. Differing from recent studies that mainly focused on how the current pandemic reduced well-being (i.e., a merely negative effect), our findings revealed both a negative impact via a material goal orientation and a positive effect via a relational goal orientation on consumer well-being. These dual effects (i.e., both negative and positive) provide a novel and enhanced view to augment understanding of the psychological processes that lead to experiences of well-being.

Third, by using a three-wave longitudinal survey in a sample in China, our results enhance comprehension of the development and changes in consumer life goals and SWB over time during the pandemic. We found that consumers’ well-being was at the lowest level during the pandemic’s advent but improved as the severity of the pandemic declined. However, this improvement trend was also partially due to consumers’ becoming acclimated to the situation. This finding is consistent with recent work that showed that people have exhibited psychological resilience and adaptation during the pandemic (e.g., Killgore et al., 2020, Petzold et al., 2020). In addition, our findings revealed that though consumers’ goal for material offerings decreased over time, their goal for social relationships remained high across the three waves of our survey.

6.2. Practical implications

Our findings offer valuable insights to augment understanding consumer preferences and behaviors and thus provide managerial implications for business and marketing during and after the pandemic. First, our results showed that consumers have placed substantial importance on material and relational goals during the pandemic. These two goals persisted across our three survey waves, thus suggesting that consumers are likely to value these two aspects in their lives over a long time span. When the pandemic may come to an end is unknown. Therefore, marketers are encouraged to improve the design of their marketing appeals to attract consumers by satisfying their goals for material offerings and social relationships.

When catering to consumers’ enhanced material goal orientation, marketers may consider creating feelings of material abundance in consumers by offering rich and varied products. Doing so would be consistent with a recent study that found that the perceived threat of the pandemic increased consumers’ tendency to choose more and varied options in multiple choice settings (Kim, 2020). Besides increasing the variety of market offerings, augmenting the status and identity signaling value of products could also be useful. Pursuing material goals is not only for survival purposes; it also offers a signaling purpose. This is especially noteworthy for luxury brands, for which there may well be increasing demand in the post-pandemic era. In fact, this supposition has received support in China. Since early April 2020—when the pandemic came under control in China—there has been tremendous growth in spending, especially on luxury goods (labeled as “revenge spending” in the news report; Williams, Hong, & Bloomberg, 2020). In the summer of 2020, revenge spending led many luxury brands to direct increased attention or pivot to China. For example, in May 2020, while Tiffany had a 40% decline in its global net sales, it experienced a 90% increase in revenue in China (Stockdrill, 2020). Our research findings revealed the potential psychological mechanism that underlies this phenomenon, and, to an extent, provided theoretical support for engaging in this managerial practice.

Marketers should also help improve the satisfaction level of their consumers’ enhanced relational goals. Given that physical distancing and stay-at-home policies still remain—and will likely continue until the pandemic is well under control marketers and brands should undertake efforts to interact with their traditional brick-and-mortar store consumers. Marketers should find new ways to facilitate the social interactions between the brand and its consumers, between consumers and their close others, and between consumers and other consumers. For instance, in China, e-commerce livestreaming has increased exponentially during the pandemic and led to an enormous boost to consumption. Such livestreaming not only provided a direct and alternative channel for shopping, but it has also served as a social space where consumers interact with the streamer, the brand, and other viewers. Consumers’ relational goals were met by their engaging in such online marketing activities. Besides these new technologies, marketing messages that feature love and relationships might also attract consumers.

Finally, our findings also have implications for promoting consumer welfare. During the pandemic, people have been helping each other by donating daily necessities, equipment for epidemic prevention, and medical appliance. These donated goods have offered abundant aid for coping with supply shortages during the pandemic. Such philanthropic behavior also conveyed care and love to the victims of the pandemic, which may contribute to their well-being resilience over time by satisfying their need for social connectedness. Governments and social institutes may seek to strengthen such feelings of social support and community in the post-pandemic period. Indeed, our results showed that such sentiments increased SWB in the long run. Consumers should also realize that pursuing material goals may counter personal well-being, but maintaining good relationships with family members and friends is beneficial for their well-being.

6.3. Limitations and future directions

Several limitations should be noted that suggest avenues for future research. First, although we employed a three-wave longitudinal design, the results were based on self-report measures. Future research may think of using secondary data and/or more objective behavioral measures, such as google search index (Brodeur et al., 2021). Linking individual-level data (e.g., consumer perceptions and evaluations) and macro-level data (e.g., consumption data) might be a valuable means to validate our findings in the marketplace. Second, the current study was based on a Chinese sample. Examining potential cultural difference vis-à-vis our findings merits empirical attention. Third, our undertaking examined the effect across three survey waves. Although we believe that our three surveyed time periods captured different development points of the pandemic in China (i.e., transmission, outbreak, and waning stages), our proposed effects may exist even in the post-pandemic era. Subsequent research may look into these effects over a longer time span than was utilized here. In addition, future studies could also examine the boundary conditions of the observed effects. For instance, consumers’ financial resources and social support may moderate the impacts of material versus relational goals on SWB.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Xiaoying Zheng is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Sun Yat-Sen University. She holds a PhD in Marketing from Peking University as well as a BS in Psychology. Her research interest includes consumer behavior, brand management and advertising. Her publications have appeared on International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, etc..

Chenhan Ruan is an Associate Professor at the School of Economy and Management at the Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University. She received her Ph.D. in Marketing from Guanghua School of Management in Peking University. Chenhan Ruan specializes in consumer behavior and her research interest focuses on understanding consumer changes in the social media age.

Lei Zheng joined the School of Economics and Management at the Fuzhou University in 2019. He received his Ph.D. in Applied Psychology from Peking University – School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences. His research focuses on the consumer’s purchase behaviors and their psychological outcomes, such as subjective well-being.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71972108, 71832015, 71602093, 72002036, 71942002), National Social Science Foundation of China (20CSH073), the Asian research center of Nankai University (AS2014), and Fujian Scientific Research Foundation for Youth Scholars of Provincial Education Department (JAS20066).

References

- Ahuvia A.C., Wong N.Y. Personality and values based materialism: Their relationship and origins. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2002;12(4):389–402. doi: 10.1016/S1057-7408(16)30089-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt J., Solomon S., Kasser T., Sheldon K.M. The urge to splurge: A terror management account of materialism and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2004;14(3):198–212. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1403_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belk R.W. Materialism: Traits aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research. 1985;12(4):265–280. doi: 10.1086/208515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn N.M. Aldine; Chicago: 1969. The structure of psychological well-being. [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Clark A.E., Fleche S., Powdthavee N. COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: evidence from google trends. Journal of Public Economics. 2021;193:104346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs J.E., Rindfleisch A. Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research. 2002;29(3):348–370. doi: 10.1086/344429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., Mathews A. Anticipatory anxiety and risk perception. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1987;11(5):551–565. doi: 10.1007/BF01183858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M.C., Jeffrey I.J., Amna K., Price L.L. In times of trouble: A framework for understanding consumers' responses to threats. Journal of Consumer Research. 2020;47(3):311–326. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucaa036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Arkin R.M. Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychology and Marketing. 2002;19(5):389–406. doi: 10.1002/mar.10016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin L.N., Hill R.P., John D.R. Poverty and materialism: A look at impoverished versus affluent children. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2014;33(1):78–92. doi: 10.1509/jppm.13.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall C.N., Richman S.B. Social exclusion and the desire to reconnect. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(11):919–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00383.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Oishi S., Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(4):253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donthu N., Gustafsson A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117(2020):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C.M., Simmering M.J., Atinc G., Atinc Y., Babin B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research. 2015;69(8):3192–3198. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Froh J.J., Fives C.J., Fuller J.R., Jacofsky M.D., Terjesen M.D., Yurkewicz C. Interpersonal relationships and irrationality as predictors of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2007;2(1):29–39. doi: 10.1080/17439760601069051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galoni, C., Carpenter, G. S., & Rao, H. (2020). Disgusted and afraid: consumer choices under the threat of contagious disease. Journal of Consumer Research, 47(3), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucaa025.

- Kasser, T., & Ahuvia, A. (2002). Materialistic values and well-being in business students. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.85.

- Kasser T., Ryan R.M. A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65(2):410–422. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T., Ryan R.M. Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(3):280–287. doi: 10.1177/0146167296223006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T., Sheldon K.M. Of wealth and death: Materialism, mortality salience, and consumption behavior. Psychological Science. 2000;11(4):348–351. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D.A. Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for spuriousness. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82(6):887–903. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.82.6.887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D., Taylor E.C., Cloonan S.A., Dailey N.S. Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291(2020) doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Impact of the perceived threat of COVID-19 on variety-seeking. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ) 2020;28(3):108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk C.P., Rifkin L.S. I'll trade you diamonds for toilet paper: Consumer reacting, coping and adapting behaviors in the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy S. The future of business education: A commentary in the shadow of the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117(2020):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H.W., Wen Z., Hau K. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(3):275–300. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A.H. Harper & Row; New York: 1954. Motivation and personality. [Google Scholar]

- Mead N.L., Baumeister R.F., Stillman T.F., Rawn C.D., Vohs K.D. Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. Journal of Consumer Research. 2011;37(5):902–919. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0334.2020.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor D., Stokes M., Firth L., Hayashi Y., Cummins R. Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitte K. Anxiety and risky decision-making: The role of subjective probability and subjective costs of negative events. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(2):243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the P.R. China. (2020). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/Accessed 10 May 2020.

- Oishi S., Kesebir S., Miao F.F., Talhelm T., Endo Y., Uchida Y.…Norasakkunkit V. Residential mobility increases motivation to expand social network: But why? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;49(2):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U., Clark D.A., Donnellan M.B., Robins R.W. Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: Comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2021;120(4):1013–1034. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold M.B., Bendau A., Plag J., Pyrkosch L., Mascarell Maricic L., Betzler F.…Ströhle A. Risk, resilience, psychological distress, and anxiety at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain and Behavior. 2020;10(9) doi: 10.1002/brb3.v10.910.1002/brb3.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the covid-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020;75(5):631–643. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoidbach J., Taquet M., Desseilles M., de Montjoye Y.A., Gross J.J. Happiness and social behavior. Psychological Science. 2019;30(8):1111–1122. doi: 10.1177/0956797619849666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L., Dawson S. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research. 1992;19(3):303–316. doi: 10.1086/209304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfleisch A., Burroughs J.E., Wong N. The safety of objects: Materialism, existential insecurity, and brand connection. Journal of Consumer Research. 2009;36(1):1–16. doi: 10.1086/595718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon K.M., Kasser T. Psychological threat and extrinsic goal striving. Motivation & Emotion. 2008;32(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s11031-008-9081-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research. 2020;117(2020):280–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrum L.J., Wong N., Arif F., Chugani S.K., Gunz A., Lowrey T.M.…Sundie J. Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research. 2013;66(8):1179–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C., Greaves C.G., Satherley L.M., Wilson N., Mueller W. Effects of the covid-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes towards government, and wellbeing. American Psychologist. 2020;75(5):618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Perception of risk. Science. 1987;236(4799):280–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3563507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears R. Social influence and group identity. Annual Review of Psychology. 2021;72(1):367–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-070620-111818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdrill, R. (2020). Is China set to rescue Tiffany &Co’s bottom line?. Insideretail. https://insideretail.asia/2020/06/09/is-china-set-to-rescue-tiffany-cos-bottom-line/ Accessed 9 June 2020.

- Tucker, H. (2020). Coronavirus bankruptcy tracker: These major companies are failing amid the shutdown. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hanktucker/2020/05/03/ coronavirus-bankruptcy-tracker-these-major-companies-are-failing-amid-the- shutdown/#5649f95d3425/ Accessed 3 May 2020.

- WHO. (2020). Investing in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/news/feature-stories/detail/investing-in-mental-health-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ Accessed 16 August 2021.

- Williams R., Hong J., & Bloomberg. (2020). Chinese luxury industry rebounds from coronavirus thanks to ‘revenge spending. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2020/03/12/chinese-luxury-industry-rebounds-coronavirus-revenge-spending/ Accessed 12 March 2020.

- WTO. (2020). How COVID-19 is changing the world. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/ccsa_publication_e.pdf/ Accessed 30 April 2020.

- Wu W., Carroll I.A., Chen P.Y. A single-level random-effects cross-lagged panel model for longitudinal mediation analysis. Behavior Research Methods. 2018;50(5):2111–2124. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0979-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Gao D.G. Social Support and Money as Pain Management Mechanisms. Psychological Inquiry. 2008;19(3–4):127–144. doi: 10.1080/10478400802587679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]