Abstract

Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase (eEF2K) acts as a negative regulator of protein synthesis, translation, and cell growth. As a structurally unique member of the alpha-kinase family, eEF2K is essential to cell survival under stressful conditions, as it contributes to both cell viability and proliferation. Known as the modulator of the global rate of protein translation, eEF2K inhibits eEF2 (eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2) and decreases translation elongation when active. eEF2K is regulated by various mechanisms, including phosphorylation through residues and autophosphorylation. Specifically, this protein kinase is downregulated through the phosphorylation of multiple sites via mTOR signaling and upregulated via the AMPK pathway. eEF2K plays important roles in numerous biological systems, including neurology, cardiology, myology, and immunology. This review provides further insights into the current roles of eEF2K and its potential to be explored as a therapeutic target for drug development.

Keywords: cancer, drug development, mTORC1, AMPK, eEF2K, immunometabolism, signaling pathways, protein kinase

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells tightly regulate protein synthesis, a biological process critical for cell survival, proliferation, and function. Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase (eEF2K) is a crucial regulator of protein synthesis via inhibiting protein translation to conserve the limited energy of the cell (Ryazanov et al., 1997). Through the lens of cancer therapeutics, eEF2K is a valid and prominent target, as primary research on focused on the protein kinase’s role in cancer. It was found that overexpression of eEF2K permits increased tumor-cell survival in many types of cancer, including breast, brain, pancreatic, and lung cancer (Karakas and Ozpolat, 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). Despite its prevalence in cancer development, eEF2K is also vital in the immune response during infection as it plays a critical role in the metabolic regulation of different immune cells. The importance of eEF2K in neurobiology as well as in myology are also active areas of research. Here, we review the recent advances in understanding the pathophysiological roles of eEF2K and its regulation. We also discuss how alterations in metabolism regulated by eEF2K relate to immunity in different pathologies.

eEF2K Structure and Function

Protein synthesis is a controlled chemical reaction that consumes an estimated 30–50% of the cell’s total energy (Browne et al., 2004). This process occurs through three principal steps: initiation, elongation, and termination, and results in the formation of a polypeptide (Griffiths, 2000). The elongation process requires substantial metabolic energy and is regulated by multiple elongation factors (Browne and Proud, 2002). One of these elongation factor regulators, eEF2K, acts by controlling elongation through phosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), reducing mRNA translation rates in cells (Hizli et al., 2013).

eEF2K is a member of the alpha-kinase family, a distinct class of kinases that have tendencies to phosphorylate molecules in alpha-helices that show little sequence homology with the conventional kinase protein family (Ryazanov et al., 1997). The alpha-kinase family represents less than ten percent of the characterized kinase proteins known to date, and other members of this class include alpha-kinase 1 (lymphocyte alpha-kinase, LAK, or ALPK1) and alpha-kinase 3 (muscle alpha-kinase, MAK, or ALPK3) (Middelbeek et al., 2010). eEF2K is dependent upon both the Ca2+ ions and calmodulin (CaM) for its kinase activity, differentiating it from other members of the alpha-kinase family that do not depend upon Ca2+/CaM-binding (Nairn and Palfrey, 1987; Ryazanov et al., 1988). Despite this, eEF2K shares no homology with other Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinases. Furthermore, eEF2K phosphorylates threonine, whereas other Ca2+/CaM kinases target serine residues (Middelbeek et al., 2010).

eEF2K consists of four main components: the calmodulin-binding domain, the catalytic domain, a regulatory loop, and a TPR-like alpha-helical region (Figure 1). The N-terminal calmodulin-binding domain is the site where CaM attaches and triggers eEF2K’s activation cascade (Pigott et al., 2012). The regulatory loop (residue 326–480) contains the most phosphorylated sites and is fundamental to the kinase’s function. It is believed that the C-terminal region neighbors a series of alpha-helical (SEL1) repeats, but a more detailed model is needed for confirmation (Mittl and Schneider-Brachert, 2007). The function of the center of SEL1 repeats is currently uncharacterized but is thought to play a role in folding and protein-protein interaction. The extreme C-terminal of eEF2K is critical for eEF2 phosphorylation, but there is no primary binding site for eEF2 (Will et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1.

This schematic outlines the structure of eEF2K and the primary functional features of the molecule. It additionally depicts the direct (solid lines) and indirect (dashed lines) signaling pathways that moderate its activity. The end of the C-terminal, shown in purple, assists the catalytic domain, characterized in yellow, to phosphorylate eEF2. The phosphorylated residues shown in green indicate sites that activate eEF2K activity, and residues in red depict inhibited eEF2K sites. The auto-phosphorylated residues that trigger eEF2K are shown in orange. Sites shown in yellow represent residues that indirectly affect the phosphorylated sites near N-terminus, and gray residues are those that have known phosphorylation activity but do not affect eEF2K activity.

eEF2K Regulation

The activity of eEF2K is regulated at several levels and is preceded by a sequential two-step mechanism. First, Ca2+ and CaM bind to the Ca2+/CaM-binding domain of eEF2K, activating its a-kinase catalytic domain. Activation of the catalytic domain is followed by rapid autophosphorylation of Thr-348, the second component of the activation mechanism. Autophosphorylation of Thr-348 triggers a conformational change of the kinase domain, increasing the activity of eEF2K (Tavares et al., 2012; Tavares et al., 2014). Although there are four other major Ca2+/CaM-stimulated autophosphorylation sites in eEF2K (Thr-353, Ser-445, Ser-474, and Ser-500), Thr-348 is the first site to be autophosphorylated and is critical for eEF2K activation (Abramczyk et al., 2011; Tavares et al., 2014). The level of eEF2K protein can also be self-regulated. A study conducted by Wang et al. showed that eEF2K stability was self-regulated, as its degradation required phosphorylation at Thr-348, which becomes the stabilized mutant T348A once degraded (Wang et al., 2015).

eEF2K is a complexly regulated protein kinase, as specific residue-phosphorylation sites can either render it active or inactive. These phosphorylation events closely correspond to the nutrient status of cells, a hallmark of cellular metabolism and health (Table 1). In the S6K-mediated pathway, ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (RPS6KB1) or p70 S6 kinase (p70S6K), which phosphorylates the S6 ribosomal protein to induce protein synthesis, can also phosphorylate eEF2K on Ser-366, rendering it inactive (Wang et al., 2001). Because multiple growth factors and MAPK signaling proteins can activate the mTOR pathway, mTOR and p70S6K serve as critical signaling proteins linking eEF2K activity and cell growth to the metabolic state of the cell (Sengupta et al., 2010).

TABLE 1.

eEF2K phosphorylated sites with their effect and mechanism.

| Residue | Mechanism | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ser-70 | mTORC1, GSK3 in vivo, insulin | Inhibitory | Wang et al. (2014) |

| Ser-78 | mTORC1 | Inhibitory | Browne and Proud (2004) |

| Pro-98 | Hydroxylation | Inhibitory | Moore et al. (2015) |

| Tyr-348 | Activation of the catalytic domain | Autophosphorylation | Abramczyk et al. (2011); Tavares et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2014) |

| Tyr-353 | - | Autophosphorylation | Tavares et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2014) |

| Ser-359 | mTORC1, ERK, P38δ, cdc2-cyclinB complex, SAPK4, agonists, insulin | Inhibitory | Knebel et al. (2001); Smith and Proud (2008); Wang et al. (2014); Wang et al. (2018) |

| Ser-366 | mTORC1, P70S6K, p90RSK1 | Inhibitory | Wang et al. (2001); Wang et al. (2014) |

| Ser-377 | Agonists, MAPKAP-K2/K3 substrate | Inhibitory | Knebel et al. (2002); Wang et al. (2018) |

| Ser-392 | mTORC1/mTORC2, insulin, GSK3 in vivo | Inhibitory | Wang et al. (2014) |

| Ser-396 | P38 MAPK in vitro, mTORC1 | Indirectly affects the phosphorylated sites | Knebel et al. (2002); Wang et al. (2014) |

| Ser-398 | AMPK | Activation | Browne and Proud (2004); Hardie (2011) |

| Ser-445 | SCF βTrCP1 ubiquitin ligase | Autophosphorylation | Kruiswijk et al. (2012); Pyr Dit Ruys et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2014) |

| Ser-470 | GSK3 in vivo, Insulin, mTORC1 | - | Wang et al. (2014) |

| Ser-474 | Autophosphorylation | Tavares et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2014) | |

| Ser-491 | AMPK | Activation | Tong et al. (2020) |

| Ser-500 | PKA substrate | Activation/Autophosphorylation | Diggle et al. (2001); Tavares et al. (2012); Tavares et al. (2014) |

Because the activity of eEF2K directly affects the rate of protein translation, it is unsurprising that eEF2K activation is sensitive to the cell’s metabolic state. Therefore, in addition to regulation by Ca2+/CaM, eEF2K is also regulated by phosphorylation via other kinases. The two primary mechanisms that regulate eEF2K phosphorylation are the mTORC1 and AMPK pathways. During nutrient deprivation, AMPK directly phosphorylates Ser-398 on eEF2K, activating the residue and upregulating eEF2K (Figure 2) (Hardie, 2011). Genotoxic stress-induced by DNA intercalating agents such as doxorubicin have also been shown to activate eEF2K through the AMPK-mediated phosphorylation on Ser-398 (Kruiswijk et al., 2012).

FIGURE 2.

Outlined are the various pathways through which eEF2K is regulated and how it ultimately impacts protein synthesis. Solid lines depict direct pathways, and indirect pathways are shown with dashed lines. eEF2 is the only substrate for eEF2K, shown in the red box. ERK regulates eEF2K in two ways: 1) direct inhibition on eEF2K and 2) the induction of p90RSK1. The regulation of STAT3 by eEF2K is under debate, but current evidence shows eEF2K inhibits STAT3 in lung cancer and activates it in liver cancer.

Ser-78 is uniquely positioned in eEF2K as it sits next to the Ca2+/CaM-binding domain (Browne and Proud, 2004). Studies have shown that mTORC1 phosphorylates Ser-78 in a rapamycin-sensitive manner and effectively prevents Ca2+/CaM binding when introduced to insulin. Lack of binding prevents eEF2K activation and allows for an increase in translation elongation activity from eEF2. Ser-498 acts similarly through increased cAMP levels to ultimately downregulate eEF2K activity via SAPK4 on Ser-359 (Knebel et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001; Will et al., 2016).

Several growth factors have been shown to affect the activity of eEF2K. For example, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) both induce the phosphorylation of Ser-359, rendering eEF2K inactive (Chen et al., 2008). eEF2K is controlled by pH, being acutely activated in cells during acidosis (Xie et al., 2015). Interestingly, eEF2K is also regulated by feedback inhibition via eEF2 activity (Mccamphill et al., 2015). Cyclin A–cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) can phosphorylate eEF2 on Ser-595, directly regulating Thr-56 phosphorylation on eEF2K (Hizli et al., 2013).

eEF2K can be regulated by post-translational modifications apart from phosphorylation. For example, eEF2K activity is inhibited when hydroxylated on proline residue 98, preventing its binding to CaM (Moore et al., 2015). This regulation is sensitive to oxygen levels, as proline hydroxylation is impaired during hypoxia and hinders protein synthesis. Subsequently, this mechanism allows cells to adapt to reduced oxygen availability. eEF2K is a target of SCF (Skp, Cullin, F-box–containing) βTrCP (β-transducin repeat-containing protein) E3 ubiquitin ligase via Ser-441 and Ser-445, which promotes its degradation and subsequent downregulation (Kruiswijk et al., 2012; Meloche and Roux, 2012). eEF2K can additionally complex with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), and disruption of the eEF2K-Hsp90 combination causes its ubiquitination and eventual degradation (Arora et al., 2005).

eEF2K Activity and Cell Signaling in Neurology

eEF2K function is crucial to the nervous system and an imperative component of certain neuro-pathologies (Park et al., 2008). Suppression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) by the antidepressant drug, ketamine, reduces the phosphorylation of eEF2 via activation of eEF2K and is the principal molecular device for controlling synaptic plasticity and memory function (Li and Tsien, 2009; Autry et al., 2011; Duman et al., 2012; Monteggia et al., 2013; Adaikkan et al., 2018). The receptor for glutamate, an excitatory amino acid transmitter, regulates eEF2K phosphorylation through the concentration of calcium ions in a timely and dose manner, which controls synaptic plasticity (Barrera et al., 2008; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009). eEF2K-defective mice with reduced kinase activity demonstrated impaired cortical-dependent associative, but not incidental, taste learning (Gildish et al., 2012).

Furthermore, recent studies have shown that eEF2K regulates protein translation in dendrites (Heise et al., 2014). Through these experiments, it was found that activation of eEF2K functioned as a biochemical sensor in dendrites where spontaneous neurotransmitter release (i.e., miniature neurotransmission) strongly promoted the phosphorylation and inactivation of eEF2 in cultured hippocampal neurons (Sutton et al., 2007). Using both pharmacological and genetic manipulation, the synthesis of proteins related to neuronal microtubule processes and intracellular trafficking such as Nsf and Map2 were found to be downstream of and regulated by eEF2K, supporting its role in neuron cytoskeleton architecture (Kenney et al., 2016). These observations suggest that changes in protein synthesis due to eEF2K inhibition are unlikely to be attributed to alterations in mRNA expression.

eEF2K function is also crucial in vascular biology in the brain (Kameshima et al., 2016) and is associated with the proliferation of rat glial cells (Bagaglio and Hait, 1994). Micro-RNAs (miRs) function in RNA silencing and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Neurons secrete exosomes containing miR-132, which are internalized to endothelial cells where they can affect eEF2K expression (Xu et al., 2017). This expression mediates the activity of miR-132 on adherens junction protein Vascular Endothelial-cadherin (VE-cadherin, also known as Cdh5) expression and brain-vascular integrity (Xu et al., 2017). Synaptic plasticity and memory are essential processes in learning that require efficient protein synthesis regulated by mTORC1 (Im et al., 2009; Kenney et al., 2015). eEF2K activity directly affects this plasticity in motor neurons, which show decreased eEF2 phosphorylation as a critical downstream effector of mTOR (Mccamphill et al., 2017).

Because eEF2K impacts synaptic plasticity, studies have been conducted to investigate the ties between eEF2K and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and epilepsy (Jan et al., 2018; Beckelman et al., 2019). Increased expression of eEF2K and decreased expression of eEF2 have been observed in the cortex and hippocampus of AD patients, alluding to the significance of eEF2K’s role in brain function and memory (Li et al., 2005; Jan et al., 2017). Ablation of eEF2K prevents amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42) oligomers from impairing synaptic plasticity, the hallmark feature in AD (Jan et al., 2017). Furthermore, the accumulation of aggregated alpha-synuclein (AS) protein in the brain, which triggers synaptic dysfunction and oxidative stress, is implicated in Parkinson’s disease (Hsu et al., 2000; Jan et al., 2018). Inhibiting eEF2K reduces these harmful AS protein aggregates by decreasing ROS and oxidative stress levels (Jan et al., 2018). The imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission has been demonstrated in the pathogenesis of epilepsy (Heise et al., 2017). A recent study indicated that eEF2K activity negatively impacts the signaling at the GABAergic synapse (Heise et al., 2017). eEF2K-deficient mice display a more robust GABAergic signaling and exhibit a rescue effect on epilepsy symptoms, suggesting that pharmacological or genetic inhibition of eEF2K could potentially counteract disease phenotypes. (Heise et al., 2017).

eEF2K in Cancer

Recent research has shown that eEF2K is associated with tumor survival, proliferation, migration, and invasion (Xie et al., 2014; Faller et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Erdogan et al., 2021; Ju et al., 2021). The proliferation of cancer cells requires a large amount of energy to grow due to the high demands of protein synthesis and the generation of building blocks. These biologic demands lead to the creation of the harsh and acidic tumor microenvironment, lacking nutrients, energy deficiency, and insufficient oxygen levels. Cancer cells invoke cytoprotective responses that trigger resistance mechanisms to assist poorly vascularized tumors in surviving this environment (Xiao et al., 2020). For instance, eEF2K is upregulated to regulate a high rate of protein synthesis (Liu et al., 2020; Erdogan et al., 2021; Temme and Asquith, 2021). A study conducted by Ju indicated that the inhibition of eEF2K, with the glutamine starvation, induces cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and 6 (CDK6), which then suppress the growth of triple-negative breast cancer (Ju et al., 2021).

AMPK activation promotes tumor cell survival by inhibiting the interaction between eEF2K and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK1/2) under nutrient deprivation. In contrast, in the presence of nutrients, eEF2K provides a positive feedback loop via MEK1/2-ERK1/2-ribosomal protein S6 kinase signaling (Tong et al., 2020). As for prostate and lung cancer cells, a study from Wu has shown that the absence of eEF2K has reduced the expression of PD-L1 protein, an immune checkpoint protein, to help cancer cells to escape from immune cells (Wu et al., 2020). In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), eEF2k express higher than non-tumor tissues, and ablation of eEF2K correlated with slower migration and proliferation rate (Zhu et al., 2017).

However, contradictory studies have surfaced at which point eEF2K disrupts the growth of certain cancers, including colon tumors, intestinal tumors, and lung tumors (Xie et al., 2014; Faller et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2020). eEF2K inhibits the aerobic glycolysis of lung cancer cells by the blockage of pyruvate kinase M2 isoform (PKM2) dimerization and inactivation of STAT3, leading to the impairment of tumor growth (Xiao et al., 2020). Surprisingly, these effects of eEF2K are independent of its function-inhibiting protein synthesis (Xiao et al., 2020). The expression of eEF2K is downregulated in colon cancer patients, which is associated with worse overall survival (Ng et al., 2019). This suggests the dual role of eEF2K in multiple cancer cell lines, and future investigation is required.

eEF2K Activity in Immune Cells and Pathologies

Cells of the immune system receive fluctuating signals to synthesize proteins at different rates in response to various physiological stresses, including temperature changes, ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, nutrient limitation, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and exposure to various drugs or toxins and infections (Holcik and Sonenberg, 2005; Mace et al., 2011; Weill et al., 2011; Buck et al., 2015).

B-cell-activating factor (BAFF) is a cytokine that belongs to the TNF superfamily and is produced by monocytes, dendritic cells, B cells, and some T cells (Mackay et al., 2007). Interestingly, the expression of eEF2K was significantly decreased in the BAFF-stimulated cells as compared to untreated control cells (Saito et al., 2008). All the three B cell leukemia cell lines, Sup-B15, Reh, and SEM, showed a decrease in the phosphorylation of the inactivating eEF2K residue Ser-366 when treated with proteasome deubiquitinase inhibitor VLX1570 and/or L-asp (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2017). Using a doxycycline (dox)- inducible system, depletion of ribosomal protein (RP) mRNA induced activation of eEF2K and eEF2 phosphorylation in human-human erythroleukemia K562C cells, resulting in inhibition of protein elongation (Gismondi et al., 2014). In a different system using an inactive mutant of the PeBoW complex, a protein complex involved in coordinating ribosome biogenesis with cell cycle progression, both eEF2K activity and expression were reduced via signaling downstream of mTOR (Holzel et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2014). These results indicate the significance of eEF2K signaling in regulating ribosome biosynthesis and function, which directly impacts cell viability.

The inflammatory response is an essential biological process that occurs during tissue injury or destruction and has a vital role in preventing the tissue from further damage. Activation of the inflammatory response may or may not be accompanied by infection. Several studies have shown the importance of eEF2K signaling pathways in inflammation and inflammatory processes. For example, eEF2K has been shown to mediate reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent vascular inflammation and is partly responsible for hypertension via propagating vascular hypertrophy and endothelial dysfunction in rats (Usui et al., 2013). eEF2K knockdown significantly inhibited monocyte adhesion to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Usui et al., 2013). One of the well-characterized inflammatory signals is the cytokine TNF-α, which has been shown to be induced by ROS in endothelial cells and is a significant contributor to inflammation (Chen et al., 2008; Peng et al., 2021). Knockdown of eEF2K significantly reduces TNF-α induced ROS production in HUVECs (Usui et al., 2013).

Viral infection can dramatically disrupt normal protein synthesis as viruses rely on the translation machinery of their host cells to produce polypeptides required for viral replication (Walsh and Mohr, 2011). Several studies have shown that pathogens, including viral and bacterial agents, disrupt the key effectors of the protein translation machinery and are essential in host defense. For example, infection of human gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cells with wild-type or the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) and virB7 mutants of H. pylori suppressed eEF2 phosphorylation at Thr-56 on eEF2K at 1 to 3 hours post-infection (Sokolova et al., 2014). CagA is an H. pylori virulence factor that is used to inject CagA into a target cell upon H. pylori attachment. The virB7 gene is among seven genes essential for CagA translocation into host cells (Fischer et al., 2001). Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) infection of cardiomyocytes causes myocarditis (Cooper, 2009). It was reported that the natural compound emodin inhibits CVB3 viral replication by suppressing viral translation elongation by activating eEF2K (Zhang et al., 2016).

Transcriptional profiling of the lymph nodes, blood, and colon samples from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIM) infected African green monkeys (AGM), and Asian pigtailed macaques (PT) showed a shift toward cellular stress pathways and Th1 profiles, with sustained and robust type I and II interferon responses (Lederer et al., 2009). In this study, eEF2K expression was dramatically increased in the lymph nodes extracted from non-pathogenic PT animals 45 days after SIV infection. Interestingly, eEF2K expression was also significantly increased in the natural host AGM animals as early as 10 days after infection. This upregulation was accompanied by CD4+ T cell depletion in multiple anatomic compartments in the PT animals.

eEF2K activity regulates protein synthesis of key proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha during liver disease. For example, the MKK3/6-p38γ/δ pathway was found to mediate inhibitory phosphorylation of eEF2K, which in turn promoted eEF2 activation (dephosphorylation) and subsequent TNF-α elongation during LPS induced liver damage (Gonzalez-Teran et al., 2013). Pathologies of the kidney, manifested by HIV infection, can be characterized by a proliferative phenotype in glomerular and tubular lesions (Rosenberg et al., 2015). Tg26 HIV transgenic mice showed an increase in mTOR activity in renal tissues accompanied by the rise in eEF2K phosphorylation (Kumar et al., 2010). Infection by bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae has been shown to affect the host response via protein translation. For example, eEF2K knock-out mice showed significantly reduced bacterial clearance in lung tissue compared to wild-type (WT) mice infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae after 24 h (Bewley et al., 2011). In a study using whole-genome arrays, gene expression profiles from circulating peripheral blood leukocytes were compiled from patients with melioidosis and tuberculosis. It was observed that eEF2K expression was significantly downregulated in patients with tuberculosis but not in patients with melioidosis, which involved three major gene sets, including glypican networks, TGF-β receptor signaling, regulation of SMAD2/3, and IFN-γ pathways (Koh et al., 2013).

The study of the role of eEF2K in T cells and its pathologies is just beginning. In T cells, eEF2K plays an essential role in cell division. For example, in response to activated protein kinase A (PKA), immortalized Jurkat cells downregulate the expression of Cyclin D3. Cyclin D3 is required for cell division and acts by decreasing the rate of translation elongation caused by increased eEF2K activity and subsequent eEF2 phosphorylation (Gutzkow et al., 2003). In a study to examine how TGF-β contributes to nephropathy, activation of eEF2 via inactivation of eEF2K by p90Rsk (Das et al., 2010) was observed. This inactivation coincided with mesangial cell hypertrophy.

Recent studies have demonstrated the significance of dysregulation of protein translation in autoimmune disorders. For example, NOD mice model the autoimmune pathology of type 1 diabetes (T1D), where the earliest signs of pathology in the pancreas occur at 4 weeks of age (Thomas and Kay, 2000). Transcriptome analysis of leukocytes extracted from the spleen of four-week-old mice showed abnormal expression of several metabolic pathway genes, including eEF2K, compared to transcript expression in spleen leukocytes from two-week-old mice (Wu et al., 2012). Further involvement of eEF2K in autoimmune disorders was revealed in a study that detected anti-eEF2K antibodies from sera of systemic lupus erythematosus patients (Arora et al., 2002). These studies highlight the advances in our understanding of the role of eEF2K in immunology.

Additional Pathologies Involved in eEF2K Regulation

Various signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of muscle tissue (Fujita et al., 2007). A Ca2+–calmodulin–eEF2K–eEF2 signaling cascade, independent of AMPK activity, was shown to contribute to suppressing skeletal muscle protein synthesis during contractions (Rose et al., 2009). One study found that eEF2K protein localized to cardiomyocytes was significantly higher in hypertrophied left ventricle tissue from spontaneously hypertensive rats than normal left ventricle tissue from normal Wistar Kyoto rats (Kameshima et al., 2016). eEF2K was found to partly mediate monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension via stimulation of vascular structural remodeling. It is currently thought that this mechanism occurs through the NADPH oxidase-1/ROS/matrix metalloproteinase-2 pathway, but further evidence is needed to validate this finding (Kameshima et al., 2015). eEF2K activity also affects the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells of the mesenteric artery of rats (Usui et al., 2015). These studies and others support eEF2K as a novel molecular target for the prevention and treatment of essential hypertension.

Muscular hypertrophy is a characteristic of multiple debilitating pathologies such as cardiomyopathy, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, debrancher enzyme deficiency, hypothyroid myopathy, and Duchenne’s and Becker’s dystrophy (Kang et al., 2016; Cariou et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2017). Several studies found that the deregulation of protein synthesis via eEF2K is implicated in these pathologies. For example, the C2C12 mouse skeletal myoblast cell line presented significantly decreased eEF2 Thr-56 phosphorylation after both static and cyclic stretching (Nakai et al., 2010). Unlike hepatocytes, murine myoblast primary cultures were sensitive to rapamycin treatment that regulates eEF2 phosphorylation (Mieulet et al., 2007). This study showed that, unlike previous reports, eEF2K activity is not directly affected by S6K signaling. The activity of eEF2K has also been reported to influence the development of atherosclerosis. It was observed that mice receiving a bone marrow transplant from eEF2K-expressing mice showed a significant decrease in atherosclerotic plaque formation via decreased M1-skewed macrophage secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (Zhang et al., 2014).

Since protein synthesis occurs in all cell types, it is not surprising that eEF2K plays a role in various biological processes, including the eye and stem cells. A recent study by Olivares et al. established a mouse model for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in which miR-883, miR-466, and miR-345, micro-RNAs that all target eEF2 were differentially expressed at various time points during retinal development as compared to the retinas from normal C57BL6/J mice (Olivares et al., 2017). Moreover, the expression of eEF2K is both growth factor- and cell line-dependent. Interestingly, eEF2K shows opposing functions in stem cells. One study showed that eEF2K knock-out mice were protected from hematopoietic syndrome yet hypersensitive to gastrointestinal syndrome (Liao et al., 2016). eEF2K also functions to maintain germline quality via regulating apoptosis by controlling translation of the anti-apoptotic proteins XIAP and c-FLIPL in oocytes from C. elegans (Chu et al., 2014).

Clinical Applications and Drug Developments

The physiological role eEF2K plays in developing and progressing several diseases, especially cancers, has led researchers to design therapeutics that target the protein kinase. eEF2K is highly expressed and regulates apoptosis, cell survival, autophagy in multiple cancer cells. Importantly, eEF2K is not required for mammalian viability or health under normal conditions (Wu et al., 2020). This leads to a pivotal role in drug development, and eEF2K is mainly being explored as a therapeutic target for numerous diseases, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular diseases (Fujita et al., 2007; Beckelman et al., 2019; Temme and Asquith, 2021). Recent research progress on eEF2K for drug development arises from generating eEF2K inhibitors (Table 2) and further starting several treatments, including PROTAC (Proteolysis target chimeric) technology and combination therapies (Zhu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020). eEF2K inhibitors for cancer therapeutics take advantage of the molecule’s signaling and regulatory pathways. Since the activation of eEF2K is related to the levels of calcium ions and AMP/ATP levels, some inhibitors, including NH125, are designed as ATP competitive inhibitors (Arora et al., 2003; Arora et al., 2004; Lockman et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2018).

TABLE 2.

The inhibitors/activators targeting eEF2K.

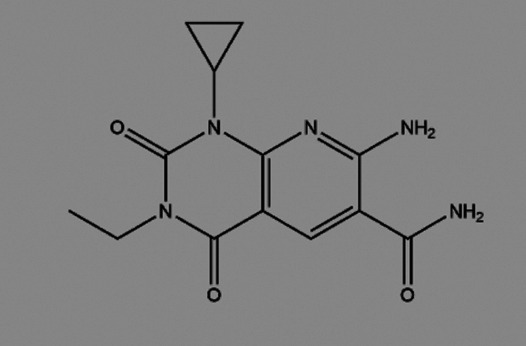

| Name of compound | Structure | Principle | Type of pathologies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A484954 (7-amino-1-cyclopropyl-3-ethyl-2,4-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrido [2,3-days] pyrimidine-6-carboxamide) |

|

ATP competitive inhibitor, but CaM-independent Demonstrates almost no cytotoxicity | Hypertension | Kodama et al. (2018); Xie et al. (2018); Kodama et al. (2019) |

| Atherosclerosis | ||||

| Breast cancer | ||||

| Lung cancer | ||||

| TNBC | ||||

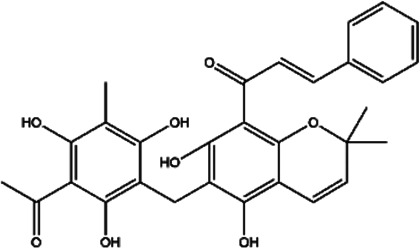

| Rottlerin (5,7-dihydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-methyl-5-acetylbenzyl)-8-cinnamoyl-1,2-chromine) |

|

Natural product, PKC δ (protein kinase Cδ) inhibitor | Glioma | Gschwendt et al. (1994) |

| Compound 34 (Thieno [2–3-b]pyridine analogues) |

|

ATP competitive inhibitor | Colorectal cancer | Lockman et al. (2010) |

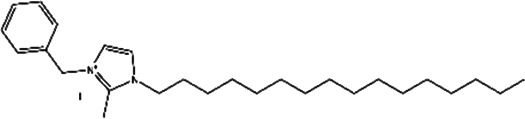

| NH125 (1-benzyl-3-cetyl-2-methylimidazolium iodide) |

|

Histidine protein kinase inhibitor, selective inhibitor of eEF2K in vitro | Glioma | Arora et al. (2003); Arora et al. (2004); Lockman et al. (2010); Zhang et al. (2011); Zhu et al. (2017); Xie et al. (2018) |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | ||||

| Breast cancer | ||||

| Lung cancer | ||||

| Geldanamycin (GA) |

|

Natural product, blockage of eEF2K and Hsp90 | Human glioma | Yang et al. (2001) |

| 17-AAG (17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) |

|

Less toxic and less potent derivative of GA, inhibitor of Hsp/protein interactions | Human glioma | Yang et al. (2001) |

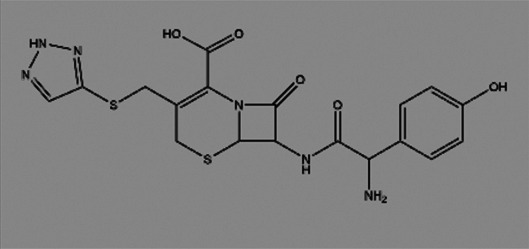

| Cefatrizine |

|

Induces ER stress | Breast cancer | Yao et al. (2016) |

| Nelfinavir (NFR) |

|

HIV aspartyl protease inhibition, also triggers eEF2K activation | - | De Gassart et al. (2016) |

| JAN-384, -452, -613, -849 | Unknown | Unknown | Breast cancer | Kenney et al. (2016); Moore et al. (2016); Xie et al. (2018) |

| Lung cancer | ||||

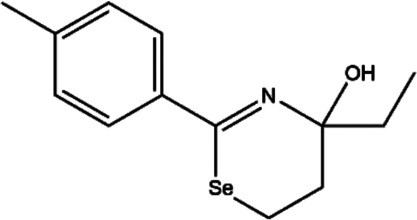

| TS-2 (4-ethyl-4-hydroxy-2-p-tolyl-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-selenazine) |

|

Multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) | None | Cho et al. (2000); Lockman et al. (2010) |

| TS-4 (4-hydroxy-6-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-p-tolyl-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-selenazine) |

|

Multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including PKA, PKC, and PTK | None | Cho et al. (2000); Lockman et al. (2010) |

| TX-1918 (2-hydroxyarylidene-4-cyclopentene-1,3-dione) |

|

Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor | TNBC | Hori et al. (2002); Ju et al. (2021) |

| Compound A1 |

|

Derived from the core structure of rottlerin; however, the detailed mechanism is unknown | TNBC | Comert Onder et al. (2020) |

| Compound A2 |

|

Derived from the core structure of rottlerin; however, the detailed mechanism is unknown | TNBC | Comert Onder et al. (2020) |

| Thymoquinone (TQ) |

|

Induction of tumor suppressor, miR-603 and NF-kB inhibition | TNBC | Kabil et al. (2018) |

| 21L (2.4-dichloro) |

|

ATP-competitive inhibitor, could stably bind to the ATP binding site of eEF2K | Breast cancer (in vivo and in vitro) | Guo et al. (2018) |

| Induces apoptosis pathway |

The development of ideal eEF2K inhibitors still faces challenges. Shortcomings regarding eEF2K inhibitors pertain to their lack of selectivity and adverse effects. eEF2K inhibitors are not selective, and this is likely attributed to the lack of the kinase’s crystal structure. Current ATP competitive inhibitors are more efficacious yet cause cytotoxicity in higher concentrations (Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, solving the crystal structure of eEF2K protein and finding proper inhibitors are still in high demand in the future.

Drug combination therapies with eEF2K inhibitors have been used to reduce doses of single drug resistance and increase the efficacy of cancer therapies. Research conducted by Zhu demonstrated the novel idea of combining an eEF2K inhibitor with radiation treatment to treat ESCC (Zhu et al., 2017). Ablation of eEF2K using pharmacological inhibitors with glutamine starvation suppresses TNBC growth (Ju et al., 2021). Silencing eEF2K suppresses the growth and induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells to a drug, doxorubicin (Tekedereli et al., 2012). Combination treatment with an eEF2K inhibitor and an AKT inhibitor (MK-2206) exert a highly anticancer effect on nasopharyngeal carcinoma and glioma (Cheng et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2018). An anticancer drug, mitoxantrone, a potential inhibitor for eEF2K, can disrupt mTOR inhibitors to enhance the efficacy of anticancer effects in breast cancer cells (Guan et al., 2020).

A novel strategy developed in 2020 targets eEF2K through a route other than inhibition. Proteolysis target chimeric (PROTAC) technology eliminates the eEF2K protein by using a protein hydrolysis mechanism. This new therapeutic mechanism has the advantage of possessing high selectivity, potentially solving the current dilemma of drug resistance. Although future optimization is required in asynchronous pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, the technology is promising (Liu et al., 2020).

Conclusion

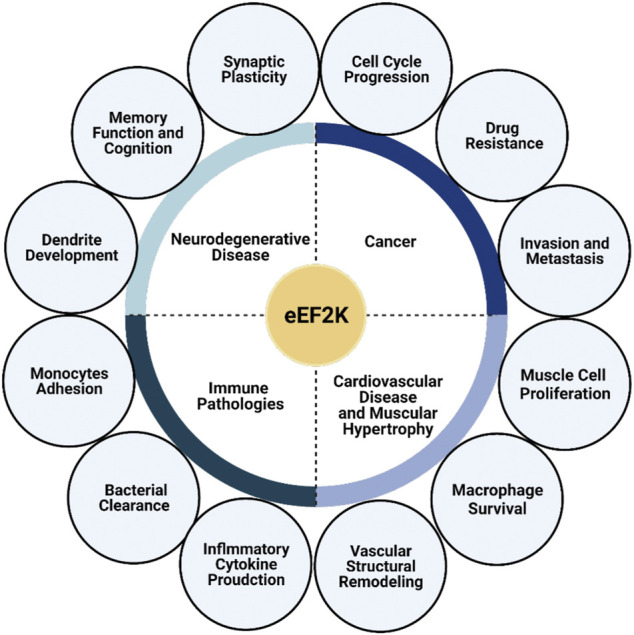

Protein translation is tightly regulated at the elongation stage of protein synthesis by eEF2K. The mechanisms which regulate eEF2K activity are varied but ultimately controlled by the nutrient status of the cell via multiple cell signaling pathways, including AMPK and mTOR. These pathways signal to increase protein synthesis when nutrients are available while decreasing protein synthesis during nutrient deprivation via eEF2K phosphorylation of its substrate, eEF2. Metabolic reprogramming via the eEF2K pathway is essential to several biological systems, especially in the nervous system and cardiology. Therefore, eEF2K is considered a potential drug target for numerous diseases, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and other immune pathologies (Figure 3). Moreover, several studies have reported the importance of eEF2K in controlling metabolic processes in immunity both during infection and in autoimmune disorders. Future studies will continue to elucidate the biological significance of this kinase in immunity. Furthermore, targeting eEF2K may help restore normal metabolism in different types of cells under various pathologic conditions.

FIGURE 3.

eEF2K plays a significant role in multiple pathologies. eEF2K is expressed at high levels in several diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, cardiovascular disease, muscular hypertrophy, and other immune pathologies, causing it to serve as a suitable and promising drug target. eEF2K affects synaptic plasticity, memory function, and dendrite development in neurology. Dysfunction of these traits leads to the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. The progression of cancer and cancer-cell growth has also been correlated with eEF2K activity and expression levels.

Author Contributions

JS and JY obtained funding and finalized the paper. DB and HP wrote the initial article. JD, AK, LW, YR, XX, and XR improved the writing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI121180 and R21AI128325 to JS, and R01CA221867 to JY and JS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abramczyk O., Tavares C. D. J., Devkota A. K., Ryazanov A. G., Turk B. E., Riggs A. F., et al. (2011). Purification and Characterization of Tagless Recombinant Human Elongation Factor 2 Kinase (eEF-2K) Expressed in Escherichia coli . Protein Expr. Purif. 79, 237–244. 10.1016/j.pep.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adaikkan C., Taha E., Barrera I., David O., Rosenblum K. (2018). Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II and Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Pathways Mediate the Antidepressant Action of Ketamine. Biol. Psychiatry 84, 65–75. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., Yang J. M., Kinzy T. G., Utsumi R., Okamoto T., Kitayama T., et al. (2003). Identification and Characterization of an Inhibitor of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase against Human Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Res. 63, 6894–6899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., Yang J. M., Utsumi R., Okamoto T., Kitayama T., Hait W. N. (2004). P-glycoprotein Mediates Resistance to Histidine Kinase Inhibitors. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 460–467. 10.1124/mol.66.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., Yang J.-M., Craft J., Hait W. (2002). Detection of Anti-elongation Factor 2 Kinase (Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase III) Antibodies in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 1073–1076. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00324-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S., Yang J.-M., Hait W. N. (2005). Identification of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway in the Regulation of the Stability of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase. Cancer Res. 65, 3806–3810. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-4036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry A. E., Adachi M., Nosyreva E., Na E. S., Los M. F., Cheng P.-f., et al. (2011). NMDA Receptor Blockade at Rest Triggers Rapid Behavioural Antidepressant Responses. Nature 475, 91–95. 10.1038/nature10130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagaglio D. M., Hait W. N. (1994). Role of Calmodulin-dependent Phosphorylation of Elongation Factor 2 in the Proliferation of Rat Glial Cells. Cell Growth Differ. 5, 1403–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera I., Hernández-Kelly L. C., Castelán F., Ortega A. (2008). Glutamate-dependent Elongation Factor-2 Phosphorylation in Bergmann Glial Cells. Neurochem. Int. 52, 1167–1175. 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckelman B. C., Yang W., Kasica N. P., Zimmermann H. R., Zhou X., Keene C. D., et al. (2019). Genetic Reduction of eEF2 Kinase Alleviates Pathophysiology in Alzheimer's Disease Model Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 820–833. 10.1172/jci122954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley M. A., Pham T. K., Marriott H. M., Noirel J., Chu H. P., Ow S. Y., et al. (2011). Proteomic Evaluation and Validation of Cathepsin D Regulated Proteins in Macrophages Exposed to Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Mol. Cel Proteomics 10, M111–M008193. 10.1074/mcp.M111.008193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G. J., Finn S. G., Proud C. G. (2004). Stimulation of the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Leads to Activation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase and to its Phosphorylation at a Novel Site, Serine 398. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12220–12231. 10.1074/jbc.m309773200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G. J., Proud C. G. (2004). A Novel mTOR-Regulated Phosphorylation Site in Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Modulates the Activity of the Kinase and its Binding to Calmodulin. Mol. Cel Biol. 24, 2986–2997. 10.1128/mcb.24.7.2986-2997.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G. J., Proud C. G. (2002). Regulation of Peptide-Chain Elongation in Mammalian Cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 5360–5368. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck M. D., O’Sullivan D., Pearce E. L. (2015). T Cell Metabolism Drives Immunity. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1345–1360. 10.1084/jem.20151159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariou E., Bennani Smires Y., Victor G., Robin G., Ribes D., Pascal P., et al. (2017). Diagnostic Score for the Detection of Cardiac Amyloidosis in Patients with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Impact on Prognosis. Amyloid 24, 101–109. 10.1080/13506129.2017.1333956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Andresen B., Hill M., Zhang J., Booth F., Zhang C. (2008). Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Induced Endothelial Dysfunction. Curr. Hypertens Rev. 4, 245–255. 10.2174/157340208786241336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Ren X., Zhang Y., Patel R., Sharma A., Wu H., et al. (2011). eEF-2 Kinase Dictates Cross-Talk between Autophagy and Apoptosis Induced by Akt Inhibition, Thereby Modulating Cytotoxicity of Novel Akt Inhibitor MK-2206. Cancer Res. 71, 2654–2663. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-10-2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Koketsu M., Ishihara H., Matsushita M., Nairn A. C., Fukazawa H., et al. (2000). Novel Compounds, '1,3-selenazine Derivatives' as Specific Inhibitors of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1475, 207–215. 10.1016/s0304-4165(00)00061-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H.-P., Liao Y., Novak J. S., Hu Z., Merkin J. J., Shymkiv Y., et al. (2014). Germline Quality Control: eEF2K Stands Guard to Eliminate Defective Oocytes. Develop. Cel 28, 561–572. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comert Onder F., Durdagi S., Sahin K., Ozpolat B., Ay M. (2020). Design, Synthesis, and Molecular Modeling Studies of Novel Coumarin Carboxamide Derivatives as eEF-2K Inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 1766–1778. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b01083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. T., Jr. (2009). Myocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1526–1538. 10.1056/nejmra0800028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M., Sossin W. S., Klann E., Sonenberg N. (2009). Translational Control of Long-Lasting Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Neuron 61, 10–26. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das F., Ghosh-Choudhury N., Kasinath B. S., Choudhury G. G. (2010). TGFβ Enforces Activation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 (eEF2) via Inactivation of eEF2 Kinase by P90 Ribosomal S6 Kinase (p90Rsk) to Induce Mesangial Cell Hypertrophy. FEBS Lett. 584, 4268–4272. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gassart A., Demaria O., Panes R., Zaffalon L., Ryazanov A. G., Gilliet M., et al. (2016). Pharmacological eEF 2K Activation Promotes Cell Death and Inhibits Cancer Progression. EMBO Rep. 17, 1471–1484. 10.15252/embr.201642194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle T. A., Subkhankulova T., Lilley K. S., Shikotra N., Willis A. E., Redpath N. T. (2001). Phosphorylation of Elongation Factor-2 Kinase on Serine 499 by cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase Induces Ca2+/calmodulin-independent Activity. Biochem. J. 353, 621–626. 10.1042/bj3530621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R. S., Li N., Liu R.-J., Duric V., Aghajanian G. (2012). Signaling Pathways Underlying the Rapid Antidepressant Actions of Ketamine. Neuropharmacology 62, 35–41. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan M. A., Ashour A., Yuca E., Gorgulu K., Ozpolat B. (2021). Targeting Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Suppresses the Growth and Peritoneal Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Cell Signal. 81, 109938. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.109938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller W. J., Jackson T. J., Knight J. R. P., Ridgway R. A., Jamieson T., Karim S. A., et al. (2015). mTORC1-mediated Translational Elongation Limits Intestinal Tumour Initiation and Growth. Nature 517, 497–500. 10.1038/nature13896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W., Püls J., Buhrdorf R., Gebert B., Odenbreit S., Haas R. (2001). Systematic Mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori Cag Pathogenicity Island: Essential Genes for CagA Translocation in Host Cells and Induction of Interleukin-8. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 1337–1348. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S., Dreyer H. C., Drummond M. J., Glynn E. L., Cadenas J. G., Yoshizawa F., et al. (2007). Nutrient Signalling in the Regulation of Human Muscle Protein Synthesis. J. Physiol. 582, 813–823. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildish I., Manor D., David O., Sharma V., Williams D., Agarwala U., et al. (2012). Impaired Associative Taste Learning and Abnormal Brain Activation in Kinase-Defective eEF2K Mice. Learn. Mem. 19, 116–125. 10.1101/lm.023937.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gismondi A., Caldarola S., Lisi G., Juli G., Chellini L., Iadevaia V., et al. (2014). Ribosomal Stress Activates eEF2K-eEF2 Pathway Causing Translation Elongation Inhibition and Recruitment of Terminal Oligopyrimidine (TOP) mRNAs on Polysomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 12668–12680. 10.1093/nar/gku996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Terán B., Cortés J. R., Manieri E., Matesanz N., Verdugo Á., Rodríguez M. E., et al. (2013). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Controls TNF-α Translation in LPS-Induced Hepatitis. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 164–178. 10.1172/jci65124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A. J. F. (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. New York: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Gschwendt M., Kittstein W., Marks F. (1994). Elongation Factor-2 Kinase: Effective Inhibition by the Novel Protein Kinase Inhibitor Rottlerin and Relative Insensitivity towards Staurosporine. FEBS Lett. 338, 85–88. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80121-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Jiang S., Ye W., Ren X., Wang X., Zhang Y., et al. (2020). Combined Treatment of Mitoxantrone Sensitizes Breast Cancer Cells to Rapalogs through Blocking eEF-2K-Mediated Activation of Akt and Autophagy. Cell Death Dis. 11, 948. 10.1038/s41419-020-03153-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Zhao Y., Wang G., Chen Y., Jiang Y., Ouyang L., et al. (2018). Design, Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationship of a Focused Library of β-phenylalanine Derivatives as Novel eEF2K Inhibitors with Apoptosis-Inducing Mechanisms in Breast Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 143, 402–418. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzkow K. B., Låhne H. U., Naderi S., Torgersen K. M., Skålhegg B., Koketsu M., et al. (2003). Cyclic AMP Inhibits Translation of Cyclin D3 in T Lymphocytes at the Level of Elongation by Inducing eEF2-Phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 15, 871–881. 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00038-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie D. G. (2011). AMP-activated Protein Kinase-Aan Energy Sensor that Regulates All Aspects of Cell Function. Genes Develop. 25, 1895–1908. 10.1101/gad.17420111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise C., Taha E., Murru L., Ponzoni L., Cattaneo A., Guarnieri F. C., et al. (2017). eEF2K/eEF2 Pathway Controls the Excitation/Inhibition Balance and Susceptibility to Epileptic Seizures. Cereb. Cortex 27, 2226–2248. 10.1093/cercor/bhw075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise C., Gardoni F., Culotta L., Di Luca M., Verpelli C., Sala C. (2014). Elongation Factor-2 Phosphorylation in Dendrites and the Regulation of Dendritic mRNA Translation in Neurons. Front. Cel. Neurosci. 8, 35. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizli A. A., Chi Y., Swanger J., Carter J. H., Liao Y., Welcker M., et al. (2013). Phosphorylation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 (eEF2) by Cyclin A-cyclin-dependent Kinase 2 Regulates its Inhibition by eEF2 Kinase. Mol. Cel Biol. 33, 596–604. 10.1128/mcb.01270-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik M., Sonenberg N. (2005). Translational Control in Stress and Apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol. 6, 318–327. 10.1038/nrm1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel M., Rohrmoser M., Schlee M., Grimm T., Harasim T., Malamoussi A., et al. (2005). Mammalian WDR12 Is a Novel Member of the Pes1-Bop1 Complex and Is Required for Ribosome Biogenesis and Cell Proliferation. J. Cel Biol. 170, 367–378. 10.1083/jcb.200501141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H., Nagasawa H., Ishibashi M., Uto Y., Hirata A., Saijo K., et al. (2002). TX-1123: an Antitumor 2-Hydroxyarylidene-4-Cyclopentene-1,3-Dione as a Protein Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Having Low Mitochondrial Toxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 3257–3265. 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L. J., Sagara Y., Arroyo A., Rockenstein E., Sisk A., Mallory M., et al. (2000). α-Synuclein Promotes Mitochondrial Deficit and Oxidative Stress. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 401–410. 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64553-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im H.-I., Nakajima A., Gong B., Xiong X., Mamiya T., Gershon E. S., et al. (2009). Post-training Dephosphorylation of eEF-2 Promotes Protein Synthesis for Memory Consolidation. PLoS One 4, e7424. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A., Jansonius B., Delaidelli A., Bhanshali F., An Y. A., Ferreira N., et al. (2018). Activity of Translation Regulator Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Is Increased in Parkinson Disease Brain and its Inhibition Reduces Alpha Synuclein Toxicity. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 6, 54. 10.1186/s40478-018-0554-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A., Jansonius B., Delaidelli A., Somasekharan S. P., Bhanshali F., Vandal M., et al. (2017). eEF2K Inhibition Blocks Aβ42 Neurotoxicity by Promoting an NRF2 Antioxidant Response. Acta Neuropathol. 133, 101–119. 10.1007/s00401-016-1634-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Y., Ben-David Y., Rotin D., Zacksenhaus E. (2021). Inhibition of eEF2K Synergizes with Glutaminase Inhibitors or 4EBP1 Depletion to Suppress Growth of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 9181. 10.1038/s41598-021-88816-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabil N., Bayraktar R., Kahraman N., Mokhlis H. A., Calin G. A., Lopez-Berestein G., et al. (2018). Thymoquinone Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion by Regulating the Elongation Factor 2 Kinase (eEF-2K) Signaling axis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 171, 593–605. 10.1007/s10549-018-4847-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameshima S., Kazama K., Okada M., Yamawaki H. (2015). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Mediates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension via Reactive Oxygen Species-dependent Vascular Remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 308, H1298–H1305. 10.1152/ajpheart.00864.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameshima S., Okada M., Yamawaki H. (2016). Expression and Localization of Calmodulin-Related Proteins in Brain, Heart and Kidney from Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 469, 654–658. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Chen Y.-C., Zhang Q. (2016). Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: A Rare Cardiac Involvement of Becker Muscular Dystrophy. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 32, 533–534. 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakas D., Ozpolat B. (2020). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase (eEF2K) Signaling in Tumor and Microenvironment as a Novel Molecular Target. J. Mol. Med. 98, 775–787. 10.1007/s00109-020-01917-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney J. W., Genheden M., Moon K.-M., Wang X., Foster L. J., Proud C. G. (2016). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Regulates the Synthesis of Microtubule-Related Proteins in Neurons. J. Neurochem. 136, 276–284. 10.1111/jnc.13407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney J. W., Sorokina O., Genheden M., Sorokin A., Armstrong J. D., Proud C. G. (2015). Dynamics of Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Regulation in Cortical Neurons in Response to Synaptic Activity. J. Neurosci. 35, 3034–3047. 10.1523/jneurosci.2866-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knebel A., Haydon C. E., Morrice N., Cohen P. (2002). Stress-induced Regulation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase by SB 203580-sensitive and −insensitive Pathways. Biochem. J. 367, 525–532. 10.1042/bj20020916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knebel A., Morrice N., Cohen P. (2001). A Novel Method to Identify Protein Kinase Substrates: eEF2 Kinase Is Phosphorylated and Inhibited by SAPK4/p38delta. EMBO J. 20, 4360–4369. 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T., Okada M., Yamawaki H. (2019). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Inhibitor, A484954 Inhibits Noradrenaline-Induced Acute Increase of Blood Pressure in Rats. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 81, 35–41. 10.1292/jvms.18-0606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T., Okada M., Yamawaki H. (2018). Mechanisms Underlying the Relaxation by A484954, a Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Inhibitor, in Rat Isolated Mesenteric Artery. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 137, 86–92. 10.1016/j.jphs.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh G. C. K. W., Schreiber M. F., Bautista R., Maude R. R., Dunachie S., Limmathurotsakul D., et al. (2013). Host Responses to Melioidosis and Tuberculosis Are Both Dominated by Interferon-Mediated Signaling. PLoS One 8, e54961. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruiswijk F., Yuniati L., Magliozzi R., Low T. Y., Lim R., Bolder R., et al. (2012). Coupled Activation and Degradation of eEF2K Regulates Protein Synthesis in Response to Genotoxic Stress. Sci. Signal. 5, ra40. 10.1126/scisignal.2002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D., Konkimalla S., Yadav A., Sataranatarajan K., Kasinath B. S., Chander P. N., et al. (2010). HIV-Associated Nephropathy. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 813–821. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer S., Favre D., Walters K.-A., Proll S., Kanwar B., Kasakow Z., et al. (2009). Transcriptional Profiling in Pathogenic and Non-pathogenic SIV Infections Reveals Significant Distinctions in Kinetics and Tissue Compartmentalization. Plos Pathog. 5, e1000296. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Tsien J. Z. (2009). Memory and the NMDA Receptors. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 302–303. 10.1056/nejmcibr0902052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Alafuzoff I., Soininen H., Winblad B., Pei J.-J. (2005). Levels of mTOR and its Downstream Targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 Kinase in Relationships with Tau in Alzheimer's Disease Brain. FEBS J. 272, 4211–4220. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Chu H.-P., Hu Z., Merkin J. J., Chen J., Liu Z., et al. (2016). Paradoxical Roles of Elongation Factor-2 Kinase in Stem Cell Survival. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 19545–19557. 10.1074/jbc.m116.724856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Iadevaia V., Averous J., Taylor P. M., Zhang Z., Proud C. G. (2014). Impairing the Production of Ribosomal RNA Activates Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 Signalling and Downstream Translation Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5083–5096. 10.1093/nar/gku130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhen Y., Wang G., Yang G., Fu L., Liu B., et al. (2020). Designing an eEF2K-Targeting PROTAC Small Molecule that Induces Apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 Cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 204, 112505. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockman J. W., Reeder M. D., Suzuki K., Ostanin K., Hoff R., Bhoite L., et al. (2010). Inhibition of eEF2-K by Thieno[2,3-B]pyridine Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 2283–2286. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace T. A., Zhong L., Kilpatrick C., Zynda E., Lee C.-T., Capitano M., et al. (2011). Differentiation of CD8+ T Cells into Effector Cells Is Enhanced by Physiological Range Hyperthermia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 951–962. 10.1189/jlb.0511229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay F., Silveira P., Brink R. (2007). B Cells and the BAFF/APRIL axis: Fast-Forward on Autoimmunity and Signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19, 327–336. 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkiewicz M., Hillert E.-K., Wang X., Pellegrini P., Olofsson M. H., Selvaraju K., et al. (2017). Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells Are Sensitive to Disturbances in Protein Homeostasis Induced by Proteasome Deubiquitinase Inhibition. Oncotarget 8, 21115–21127. 10.18632/oncotarget.15501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccamphill P. K., Farah C. A., Anadolu M. N., Hoque S., Sossin W. S. (2015). Bidirectional Regulation of eEF2 Phosphorylation Controls Synaptic Plasticity by Decoding Neuronal Activity Patterns. J. Neurosci. 35, 4403–4417. 10.1523/jneurosci.2376-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccamphill P. K., Ferguson L., Sossin W. S. (2017). A Decrease in Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Phosphorylation Is Required for Local Translation of Sensorin and Long-Term Facilitation in Aplysia. J. Neurochem. 142, 246–259. 10.1111/jnc.14030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloche S., Roux P. P. (2012). F-box Proteins Elongate Translation during Stress Recovery. Sci. Signal. 5, pe25. 10.1126/scisignal.2003163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbeek J., Clark K., Venselaar H., Huynen M. A., Van Leeuwen F. N. (2010). The Alpha-Kinase Family: an Exceptional branch on the Protein Kinase Tree. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 875–890. 10.1007/s00018-009-0215-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieulet V., Roceri M., Espeillac C., Sotiropoulos A., Ohanna M., Oorschot V., et al. (2007). S6 Kinase Inactivation Impairs Growth and Translational Target Phosphorylation in Muscle Cells Maintaining Proper Regulation of Protein Turnover. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C712–C722. 10.1152/ajpcell.00499.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittl P. R. E., Schneider-Brachert W. (2007). Sel1-like Repeat Proteins in Signal Transduction. Cell Signal. 19, 20–31. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteggia L. M., Gideons E., Kavalali E. T. (2013). The Role of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase in Rapid Antidepressant Action of Ketamine. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 1199–1203. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. E. J., Mikolajek H., Regufe Da Mota S., Wang X., Kenney J. W., Werner J. M., et al. (2015). Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Is Regulated by Proline Hydroxylation and Protects Cells during Hypoxia. Mol. Cel. Biol. 35, 1788–1804. 10.1128/mcb.01457-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. E. J., Wang X., Xie J., Pickford J., Barron J., Regufe Da Mota S., et al. (2016). Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Promotes Cell Survival by Inhibiting Protein Synthesis without Inducing Autophagy. Cell Signal. 28, 284–293. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn A. C., Palfrey H. C. (1987). Identification of the Major Mr 100,000 Substrate for Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase III in Mammalian Cells as Elongation Factor-2. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 17299–17303. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)45377-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai N., Kawano F., Oke Y., Nomura S., Ohira T., Fujita R., et al. (2010). Mechanical Stretch Activates Signaling Events for Protein Translation Initiation and Elongation in C2C12 Myoblasts. Mol. Cell 30, 513–518. 10.1007/s10059-010-0147-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T. H., Sham K. W. Y., Xie C. M., Ng S. S. M., To K. F., Tong J. H. M., et al. (2019). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Expression Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in Colorectal Cancer. BMC Cancer 19, 649. 10.1186/s12885-019-5873-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares A. M., Jelcick A. S., Reinecke J., Leehy B., Haider A., Morrison M. A., et al. (2017). Multimodal Regulation Orchestrates Normal and Complex Disease States in the Retina. Sci. Rep. 7, 690. 10.1038/s41598-017-00788-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Park J. M., Kim S., Kim J.-A., Shepherd J. D., Smith-Hicks C. L., et al. (2008). Elongation Factor 2 and Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein Control the Dynamic Translation of Arc/Arg3.1 Essential for mGluR-LTD. Neuron 59, 70–83. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H.-Y., Lucavs J., Ballard D., Das J. K., Kumar A., Wang L., et al. (2021). Metabolic Reprogramming and Reactive Oxygen Species in T Cell Immunity. Front. Immunol. 12, 652687. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.652687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott C. R., Mikolajek H., Moore C. E., Finn S. J., Phippen C. W., Werner J. M., et al. (2012). Insights into the Regulation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase and the Interplay between its Domains. Biochem. J. 442, 105–118. 10.1042/bj20111536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyr Dit Ruys S., Wang X., Smith E. M., Herinckx G., Hussain N., Rider M. H., et al. (2012). Identification of Autophosphorylation Sites in Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase. Biochem. J. 442, 681–692. 10.1042/bj20111530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A. J., Alsted T. J., Jensen T. E., Kobberø J. B., Maarbjerg S. J., Jensen J., et al. (2009). A Ca2+-Calmodulin-eEF2K-eEF2 Signalling cascade, but Not AMPK, Contributes to the Suppression of Skeletal Muscle Protein Synthesis during Contractions. J. Physiol. 587, 1547–1563. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A. Z., Naicker S., Winkler C. A., Kopp J. B. (2015). HIV-associated Nephropathies: Epidemiology, Pathology, Mechanisms and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 11, 150–160. 10.1038/nrneph.2015.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov A. G., Natapov P. G., Shestakova E. A., Severin F. F., Spirin A. S. (1988). Phosphorylation of the Elongation Factor 2: The Fifth Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent System of Protein Phosphorylation☆. Biochimie 70, 619–626. 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90245-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov A. G., Ward M. D., Mendola C. E., Pavur K. S., Dorovkov M. V., Wiedmann M., et al. (1997). Identification of a New Class of Protein Kinases Represented by Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94, 4884–4889. 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y., Miyagawa Y., Onda K., Nakajima H., Sato B., Horiuchi Y., et al. (2008). B-cell-activating Factor Inhibits CD20-Mediated and B-Cell Receptor-Mediated Apoptosis in Human B Cells. Immunology 125, 570–590. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02872.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Peterson T. R., Sabatini D. M. (2010). Regulation of the mTOR Complex 1 Pathway by Nutrients, Growth Factors, and Stress. Mol. Cel 40, 310–322. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. M., Proud C. G. (2008). cdc2-cyclin B Regulates eEF2 Kinase Activity in a Cell Cycle- and Amino Acid-dependent Manner. EMBO J. 27, 1005–1016. 10.1038/emboj.2008.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova O., Vieth M., Gnad T., Bozko P. M., Naumann M. (2014). Helicobacter pylori Promotes Eukaryotic Protein Translation by Activating Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/mTOR. Int. J. Biochem. Cel Biol. 55, 157–163. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. A., Taylor A. M., Ito H. T., Pham A., Schuman E. M. (2007). Postsynaptic Decoding of Neural Activity: eEF2 as a Biochemical Sensor Coupling Miniature Synaptic Transmission to Local Protein Synthesis. Neuron 55, 648–661. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares C. D. J., Ferguson S. B., Giles D. H., Wang Q., Wellmann R. M., O'brien J. P., et al. (2014). The Molecular Mechanism of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23901–23916. 10.1074/jbc.m114.577148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares C. D. J., O’Brien J. P., Abramczyk O., Devkota A. K., Shores K. S., Ferguson S. B., et al. (2012). Calcium/calmodulin Stimulates the Autophosphorylation of Elongation Factor 2 Kinase on Thr-348 and Ser-500 to Regulate its Activity and Calcium Dependence. Biochemistry 51, 2232–2245. 10.1021/bi201788e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekedereli I., Alpay S. N., Tavares C. D. J., Cobanoglu Z. E., Kaoud T. S., Sahin I., et al. (2012). Targeted Silencing of Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Suppresses Growth and Sensitizes Tumors to Doxorubicin in an Orthotopic Model of Breast Cancer. PLoS One 7, e41171. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temme L., Asquith C. R. M. (2021). eEF2K: an Atypical Kinase Target for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 577. 10.1038/d41573-021-00124-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. E., Kay T. W. H. (2000). Beta Cell Destruction in the Development of Autoimmune Diabetes in the Non-obese Diabetic (NOD) Mouse. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 16, 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S., Zhou T., Meng Y., Xu D., Chen J. (2020). AMPK Decreases ERK1/2 Activity and Cancer Cell Sensitivity to Nutrition Deprivation by Mediating a Positive Feedback Loop Involving eEF2K. Oncol. Lett. 20, 61–66. 10.3892/ol.2020.11554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T., Nijima R., Sakatsume T., Otani K., Kameshima S., Okada M., et al. (2015). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Controls Proliferation and Migration of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Acta Physiol. 213, 472–480. 10.1111/apha.12354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T., Okada M., Hara Y., Yamawaki H. (2013). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Regulates the Development of Hypertension through Oxidative Stress-dependent Vascular Inflammation. Am. J. Physiol.Heart Circ. Physiol. 305, H756–H768. 10.1152/ajpheart.00373.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D., Mohr I. (2011). Viral Subversion of the Host Protein Synthesis Machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 860–875. 10.1038/nrmicro2655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li W., Williams M., Terada N., Alessi D. R., Proud C. G. (2001). Regulation of Elongation Factor 2 Kinase by p90RSK1 and P70 S6 Kinase. EMBO J. 20, 4370–4379. 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Regufe Da Mota S., Liu R., Moore C. E., Xie J., Lanucara F., et al. (2014). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Activity Is Controlled by Multiple Inputs from Oncogenic Signaling. Mol. Cel Biol. 34, 4088–4103. 10.1128/mcb.01035-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Xie J., Da Mota S. R., Moore C. E., Proud C. G. (2015). Regulated Stability of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Requires Intrinsic but Not Ongoing Activity. Biochem. J. 467, 321–331. 10.1042/bj20150089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang G., Wang Z., Qin H., Mo B., Wang C. (2018). Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Acts Downstream of P38 MAPK to Regulate Proliferation, Apoptosis and Autophagy in Human Lung Fibroblasts. Exp. Cel Res. 363, 291–298. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weill F. S., Cela E. M., Ferrari A., Paz M. L., Leoni J., González Maglio D. H. (2011). Skin Exposure to Chronic but Not Acute UV Radiation Affects Peripheral T-Cell Function. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 74, 838–847. 10.1080/15287394.2011.570228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will N., Piserchio A., Snyder I., Ferguson S. B., Giles D. H., Dalby K. N., et al. (2016). Structure of the C-Terminal Helical Repeat Domain of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase. Biochemistry 55, 5377–5386. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Kakoola D. N., Lenchik N. I., Desiderio D. M., Marshall D. R., Gerling I. C. (2012). Molecular Phenotyping of Immune Cells from Young NOD Mice Reveals Abnormal Metabolic Pathways in the Early Induction Phase of Autoimmune Diabetes. PLoS One 7, e46941. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.-M., An D.-A. L., Yao Q.-Y., Ou Y.-R. Z., Lu Q., Jiang M., et al. (2017). Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in Hypertensive Heart Disease with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insight from Altered Mechanics and Native T1 Mapping. Clin. Radiol. 72, 835–843. 10.1016/j.crad.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Xie J., Jin X., Lenchine R. V., Wang X., Fang D. M., et al. (2020). eEF2K Enhances Expression of PD-L1 by Promoting the Translation of its mRNA. Biochem. J. 477, 4367–4381. 10.1042/bcj20200697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M., Xie J., Wu Y., Wang G., Qi X., Liu Z., et al. (2020). The eEF2 Kinase-Induced STAT3 Inactivation Inhibits Lung Cancer Cell Proliferation by Phosphorylation of PKM2. Cell Commun Signal 18, 25. 10.1186/s12964-020-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C.-M., Liu X.-Y., Sham K. W., Lai J. M., Cheng C. H. (2014). Silencing of EEF2K (Eukaryotic Elongation Factor-2 Kinase) Reveals AMPK-ULK1-dependent Autophagy in colon Cancer Cells. Autophagy 10, 1495–1508. 10.4161/auto.29164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Mikolajek H., Pigott C. R., Hooper K. J., Mellows T., Moore C. E., et al. (2015). Molecular Mechanism for the Control of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase by pH: Role in Cancer Cell Survival. Mol. Cel. Biol. 35, 1805–1824. 10.1128/mcb.00012-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Shen K., Lenchine R. V., Gethings L. A., Trim P. J., Snel M. F., et al. (2018). Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Upregulates the Expression of Proteins Implicated in Cell Migration and Cancer Cell Metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 142, 1865–1877. 10.1002/ijc.31210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Zhang Y., Du X.-F., Li J., Zi H.-X., Bu J.-W., et al. (2017). Neurons Secrete miR-132-Containing Exosomes to Regulate Brain Vascular Integrity. Cell Res 27, 882–897. 10.1038/cr.2017.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Yang J. M., Iannone M., Shih W. J., Lin Y., Hait W. N. (2001). Disruption of the EF-2 kinase/Hsp90 Protein Complex: a Possible Mechanism to Inhibit Glioblastoma by Geldanamycin. Cancer Res. 61, 4010–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Li J., Liu Z., Zheng L., Fan N., Zhang Y., et al. (2016). Integrative Bioinformatics and Proteomics-Based Discovery of an eEF2K Inhibitor (Cefatrizine) with ER Stress Modulation in Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Biosyst. 12, 729–736. 10.1039/c5mb00848d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. M., Wang F., Qiu Y., Ye X., Hanson P., Shen H., et al. (2016). Emodin Inhibits Coxsackievirus B3 Replication via Multiple Signalling Cascades Leading to Suppression of Translation. Biochem. J. 473, 473–485. 10.1042/bj20150419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Riazy M., Gold M., Tsai S.-H., Mcnagny K., Proud C., et al. (2014). Impairing Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Activity Decreases Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. Can. J. Cardiol. 30, 1684–1688. 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cheng Y., Zhang L., Ren X., Huber-Keener K. J., Lee S., et al. (2011). Inhibition of eEF-2 Kinase Sensitizes Human Glioma Cells to TRAIL and Down-Regulates Bcl-xL Expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414, 129–134. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.-y., Tian Y., Liu L., Zhan J.-h., Hou X., Chen X., et al. (2018). Inhibiting eEF-2 Kinase-Mediated Autophagy Enhanced the Cytocidal Effect of AKT Inhibitor on Human Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 12, 2655–2663. 10.2147/dddt.s169952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Song H., Chen G., Yang X., Liu J., Ge Y., et al. (2017). eEF2K Promotes Progression and Radioresistance of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Radiother. Oncol. 124, 439–447. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]