Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the role of bioimpedance-defined overhydration (BI-OH) parameters in predicting the risk of mortality and cardiovascular (CV) events in patients undergoing dialysis.

Methods

We searched multiple electronic databases for studies investigating BI-OH indicators in the prediction of mortality and CV events through 23 May 2020. We assessed the effect of BI-OH indexes using unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sensitivity analysis was used for each outcome.

Results

We included 55 studies with 104,758 patients in the meta-analysis. Extracellular water/total body water (ECW/TBW) >0.4 (HR 5.912, 95% CI: 2.016–17.342), ECW/intracellular water (ICW) for every 0.01 increase (HR 1.041, 95% CI: 1.031–1.051), and OH/ECW >15% (HR 2.722, 95% CI: 2.005–3.439) increased the risk of mortality in patients receiving dialysis. ECW/TBW >0.4 (HR 2.679, 95% CI: 1.345–5.339) and ECW/ICW per increment of 10% (HR 1.032, 95% CI: 1.017–1.047) were associated with an increased risk of CV events in patients undergoing dialysis. A 1-degree increase in phase angle was a protective factor for both mortality (HR 0.676, 95% CI: 0.474–0.879) and CV events (HR 0.736, 95% CI: 0.589–0.920).

Conclusions

BI-OH parameters might be independent predictors for mortality and CV events in patients undergoing dialysis.

Keywords: Bioimpedance-defined overhydration, mortality, cardiovascular event, dialysis, meta-analysis, outcome

Introduction

As a renal replacement therapy, renal dialysis is, in principle, a selective treatment for renal dysfunction or renal diseases that includes peritoneal dialysis (PD) or hemodialysis (HD).1 Following a rapid increase in dialysis use over a period of approximately two decades, the incidence of dialysis initiation in most high-income countries reached a peak in the early 2000s and has remained stable or has decreased slightly since then.2 However, mortality remains unacceptably high among patients on dialysis, especially in the first 3 months following initiation of HD treatment. According to the 2019 Annual Data Report from the U.S. Renal Data System, the annual mortality was 156 per 1000 patient-years for patients undergoing PD and 167 patients for those receiving HD in the United States.3

Overhydration (OH) is relatively common among patients receiving dialysis, with an incidence of 56.5% to 73.1%.4–6 Observational studies have shown an association between OH and mortality in patients receiving dialysis.7,8 Therefore, it is essential to objectively measure patients’ hydration status to obtain a more clearly defined assessment of prognosis in patients on dialysis. Common clinical approaches, such as measuring weight changes and the isotope dilution method, have certain limitations, which have led to the development of bioimpedance analysis (BIA).9–11 Bioimpedance-defined overhydration (BI-OH) indicators have been suggested to predict mortality risk and cardiovascular (CV) events in patients receiving dialysis.9,12 Previous studies have indicated that phase angle (PA) level is linked to a decreased risk of death among patients undergoing PD or HD.13,14 Other evidence suggests that a higher extracellular water (ECW)/intracellular water (ICW) ratio, ECW/total body water (TBW) ratio >0.4, and overhydration (OH)/ECW ratio >15% are independent risk factors for mortality and CV events in patients undergoing HD or PD treatment.15–18 However, Rhee et al. and Shin et al. demonstrated that a 1-degree increase in PA was not associated with increased risk of mortality and CV events in patients undergoing dialysis, without statistical significance.14,19 A post-hoc study from a cross-sectional survey by Guo et al. found that ECW/TBW >0.4 had no effect on CV events, with P>0.05.20

A newly published meta-analysis predicted the risk of death in patients with renal and heart failure using a 1-degree decrease in PA and OH/ECW >15%.12 Nevertheless, the role of specific OH parameters in predicting the risk of death and CV events in patients receiving dialysis remains unclear. To further clarify the correlation between OH parameters measured using BIA and the above clinical outcomes in patients on dialysis, we conducted a meta-analysis adding measures such as ECW/TBW >0.4 and ECW/ICW per every 0.01 increase, as well as subgroup analysis of dialysis methods and literature quality.

Methods

In this meta-analysis, approval of the Institutional Review Board and informed consent were not required. Our study was performed and documented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Material). The supplementary material describes the methods of this study in detail. The present study was approved by the Open Science Framework Registries (https://osf.io/registries), registration number 10.17605/OSF.IO/H2KJ4.

Literature search strategy

We performed a search of the published literature in the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases up to 23 May 2020. The keywords in the search strategy were as follows: dialysis, renal dialysis, renal insufficiency, chronic kidney failure, and electric impedance. The search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows. i) Patients with renal diseases including chronic renal insufficiency, end-stage renal disease, renal failure, and other renal diseases, and were undergoing PD or HD. ii) BIA and its parameter indexes were ECW/TBW >0.4,9 ECW/ICW, OH/ECW>15%,21 and PA. iii) The outcomes were unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of mortality (main outcome) and unadjusted HR of CV events (secondary outcome). When multiple follow-up time points of the outcome event were reported, the final follow-up time point at which the outcome event occurred was included in the analysis. iv) Cohort studies.

Exclusion criteria were: i) animal studies; ii) non-English language international publications; iii) studies with unavailable data; and iv) case reports, meeting abstracts, meta-analyses, reviews, or editorials.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The literature was reviewed and the research data were extracted by two researchers (Yajie Wang and Zejuan Gu) according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the case of a conflict, the point of disagreement was discussed between the two parties until agreement was reached. The following information was collected from the studies: first author, year of publication, country, method of renal replacement therapy, number of patients, age, body mass index, sex, follow-up, primary outcome, secondary outcome, mortality, BIA method, Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) score, and quality assessment score. The quality of the articles was evaluated using the NOS, with scores ranging from 0 to 10. “Low quality” studies were defined as those with scores <5 and those with scores ≥5 were considered “high quality” studies.

Statistical analysis

The data were evaluated using unadjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to determine effect sizes. To evaluate heterogeneity for each outcome, random-effects (I2≥50%) and fixed-effects (I2<50%) models were used. When I2≥50% and P<0.05, subgroup analysis was carried out for the dialysis method and literature quality. We performed sensitivity analysis for all outcomes. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using R studio 4.0.3 (www.r-project.org; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

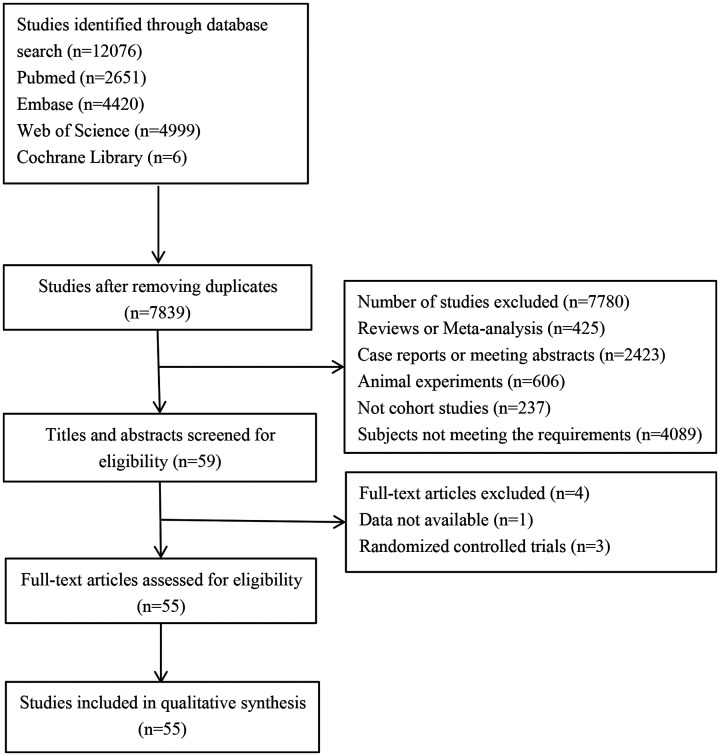

In a search of the selected electronic databases, 12,076 studies were initially identified in total. After removing duplicates, 7839 studies for subsequently screened. Finally, 55 studies were included.5,7,13–65 A flow diagram of the complete search strategy, article screening, and exclusion and inclusion processes in this review are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature search.

There was a total of 104,758 participants in the 55 studies, with follow-up times ranging from 1 to 15 years. A total of 14,624 patients died, with up to 15 years of follow-up. Among the 55 studies, 32 were assessed as high quality and 23 as low quality. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Dialysis method | N | Age, years | BMI, kg/m2 | Male/Female | Follow-up (years) | Primary outcome | Secondary outcome | Mortality | BIA method | NOS score | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abad22 | 2011 | Spain | 127 HD, 37 PD | 164 | 61.1±14.5 | 25.3±5.0 | 99/65 | 6 | Mortality | NA | 100 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Avram23 | 2006 | USA | PD | 177 | 54±16 | 25.4±4.94 | 73/104 | 15 | Mortality | NA | 89 | PA | 2 | LQ |

| Beberashvili24 | 2014 | Israel | HD | 91 | 64.0±11.5 | 28.1±5.5 | 57/34 | 3 | Mortality | NA | 38 | PA | 6 | HQ |

| Beberashvili (1)25 | 2014 | Israel | HD | 250 | 68.7±13.6 | 26.6± 4.5 | 158/92 | 1.4 | Mortality | NA | 64 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Caetano26 | 2016 | Portugal | HD | 697 | 67 (55.5–76)* | (25–29.9)* | 394/303 | 1 | Mortality | NA | 66 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Chazot7 | 2012 | France | HD | 158 | 64.7±13.8 | 26.9±5.1 | 78/80 | 6.5 | Mortality | Hypertension | unclear | OHI | 4 | LQ |

| Chen27 | 2007 | China | PD | 227 | 59.53±14.37 | 23.27±3.57 | 100/127 | 3 | Mortality | NA | 58 | ECWR | 5 | HQ |

| de Araujo28 | 2012 | Brazil | 109 HD, 36 PD | 145 | 54.9±15.4 | 24.7 (21.9–28.7)* | 72/73 | 1.3 | CV events | Mortality | 13 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Dekker29 | 2017 | International | HD | 8883 | 63±14.8 | NA | 5081/3802 | 1 | Mortality | NA | unclear | OHI | 4 | LQ |

| Demirci30 | 2016 | Turkey | HD | 493 | 57.7±13.9 | 26.1±4.8 | 253/240 | 2.3 | Mortality | CV mortality | 93 | BIVA | 5 | HQ |

| Di Iorio52 | 2004 | Italy | HD | 515 | 63.62±15.35 | 24.56±4.45 | 316/199 | 1.25 | Mortality | NA | 75 | PA | 4 | LQ |

| Fan31 | 2015 | UK | PD | 183 | 54.9±15.6 | NA | 95/88 | 1.7 | Mortality | Technique failure | 37 | ECWR | 4 | LQ |

| Fein53 | 2002 | USA | PD | 53 | 53 | NA | 17/36 | 8 | Mortality | NA | 21 | ECWR | 3 | LQ |

| Fiedler32 | 2009 | Germany | HD | 90 | 61±14 | NA | 53/37 | 3 | Mortality | Hospital admission events | 36 | PA | 4 | LQ |

| Guo5 | 2015 | China | PD | 307 | 47.8±15.3 | 22.7±3.9 | 132/175 | 3.2 | Mortality | CV mortality | 52 | ECWR | 6 | HQ |

| Hoppe33 | 2015 | Poland | HD | 241 | 61.9±12.5 | 26.1±3.9 | 160/81 | 2.5 | Mortality | NA | 42 | OHI | 1 | LQ |

| Jotterand Drepper34 | 2016 | Germany | PD | 54 | 56.1± 15.5 | 25.5±3.6 | 33/21 | 6.5 | Mortality | NA | 19 | OHI | 4 | LQ |

| Kim36 | 2015 | South Korea | HD | 240 | 65.6±12.8 | NA | 147/93 | 2 | Mortality | Hospital admission events | 50 | OHI | 4 | LQ |

| Kim35 | 2017 | South Korea | HD | 77 | 52.6±12.5 | NA | 40/37 | 5 | Mortality | CV events | 24 | ECWR | 4 | LQ |

| Koh37 | 2011 | Malaysia | PD | 128 | 48.0±1.2 | 24.3±0.4 | 59/69 | 2.2-2.3 | Mortality | NA | 35 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Maggiore54 | 1996 | Italy | HD | 131 | 62.5±13.6 | NA | 66/65 | 2.2 | Mortality | NA | 23 | PA | 4 | LQ |

| Mathew38 | 2015 | India | 85 HD, 14 PD | 99 | 55.26±12.5 | 22.23±4.2 | 78/21 | 2 | Mortality | NA | 33 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| O’Lone40 | 2014 | UK | PD | 529 | 57.0 (46.7–68.8)* | NA | 329/200 | 4 | Mortality | NA | 95 | OHI+ECWR | 4 | LQ |

| Oei39 | 2016 | UK | PD | 336 | 57.9 (48.1–69.0)* | NA | 207/129 | 2 | Mortality | NA | 48 | OHI | 4 | LQ |

| Onofriescu41 | 2015 | Romania | HD | 221 | 53.8±13.9 | 25.5±5.0 | 116/105 | 5.5 | Mortality | CV events | 66 | OHI | 6 | HQ |

| Paniagua42 | 2010 | Mexico | 388 HD, 365 PD | 753 | 48.64±17.55 | 25.22±5.15 | 415/338 | 1.4 | Mortality | CV mortality | 182 | ECWR | 5 | HQ |

| Paudel43 | 2015 | UK | PD | 455 | 56.1± 0.7 | 26.8±0.3 | 278/177 | 2 | Mortality | NA | 72 | OHI | 3 | LQ |

| Pillon55 | 2004 | USA | HD | 3009 | 60.5±15.4 | NA | 1589/1420 | 1.5 | Mortality | NA | 361 | BIVA | 4 | LQ |

| Pupim56 | 2004 | USA | HD | 194 | 55.7±15.4 | NA | 102/92 | 3 | Mortality | CV mortality | 50 | PA | 4 | LQ |

| Rhee64 | 2015 | South Korea | PD | 129 | 49.74±10.01 | 23.59±3.31 | 80/49 | 2.1 | residual renal function | Mortality | 15 | ECWR | 3 | LQ |

| Segall45 | 2014 | Romania | HD | 149 | 53.9±13.7 | 22.8±8.1 | 82/67 | 1.1 | Mortality | NA | 43 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Shin14 | 2017 | South Korea | HD | 142 | 64±13 | 22.5 (20.4, 24.9)* | 75/67 | 2.4 | Mortality | CV mortality | 15 | PA | 3 | LQ |

| Siriopol47 | 2015 | Romania | HD | 173 | 57.9±14.0 | NA | 85/88 | 1.8 | Mortality | NA | 31 | OHI | 3 | LQ |

| Siriopol (1)48 | 2017 | Romania | HD | 285 | 58.9 ±14.1 | NA | 136/149 | 3.4 | Mortality | NA | 89 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Tangvoraphonchai49 | 2016 | UK | HD | 362 | 63 (50–76)* | NA | 216/146 | 4.1 | Mortality | NA | 110 | OHI | 6 | HQ |

| Tian50 | 2016 | China | PD | 152 | 60.5±12.8 | 24.0±3.8 | 62/90 | 5 | Mortality | NA | 44 | ECWR | 4 | LQ |

| Wizemann21 | 2009 | Poland | HD | 269 | 65±15 | 25.6±4.7 | NA | 3.5 | Mortality | NA | 86 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Zoccali18 | 2017 | International | HD | 39,566 | 60.9±15.7 | 27.1±18.5 | 23593/15973 | 1.4 | Mortality | NA | 5866 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Arrigo57 | 2018 | Switzerland | HD | 144 | 73 (59–81)* | NA | 88/56 | 1 | Mortality | NA | 27 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Avram58 | 2010 | USA | PD | 62 | 54±16 | NA | 28/34 | 8 | Mortality | NA | 21 | ECWR | 6 | HQ |

| Bansal59 | 2018 | USA | HD | 3751 | 58.1±11.6 | 29.0±5.9 | 2047/1704 | 7 | Mortality | CV events | 776 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Beberashvili60 | 2010 | Israel | HD | 81 | 64.3±11.9 | 28.3±5.6 | 53/28 | 2.2 | Mortality | NA | 22 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Ng15 | 2018 | China | PD | 311 | 58.8±12.2 | 24.9±4.3 | 172/139 | 2.2 | Mortality | CV events | 81 | OHI+ECWR | 4 | LQ |

| Hecking61 | 2018 | Germany | HD | 38,614 | 60.9±15.7 | 25.9±5.3 | 23011/15603 | 1 | Mortality | NA | 5640 | OHI | 7 | HQ |

| Huang62 | 2018 | China | HD | 178 | 60.9±11.6 | 23.9±3.8 | 87/91 | 2.7 | Mortality | CV mortality | 24 | OHI | 5 | HQ |

| Huang13 | 2019 | China | PD | 760 | 45.2±14.5 | 22.5±3.2 | 465/295 | 2 | Mortality | CV events | 125 | PA | 5 | HQ |

| Kim17 | 2018 | South Korea | HD | 142 | 64±13 | 23.4±8.5 | 75/67 | 2.4 | Mortality | CV events | 15 | ECWR | 6 | HQ |

| Mushbick63 | 2003 | USA | PD | 48 | 51±15 | 25.7±5.0 | 25/23 | 2 | Mortality | NA | 8 | PA | 3 | LQ |

| Rhee19 | 2018 | South Korea | HD | 208 | 65.19±12.9 | 22.62±3.21 | 208/0 | 1 | Mortality | NA | 84 | ECWR+PA | 6 | HQ |

| Voroneanu65 | 2014 | Romania | HD | 98 | 55.4±13.2 | NA | 49/49 | 2 | Mortality | CV mortality | 16 | N- proBNP and hs–cTnT | 5 | HQ |

| Yajima16 | 2019 | Japan | HD | 234 | 65.1±12.6 | 22.0±3.8 | 162/72 | 2.8 | Mortality | CV mortality | 72 | ECWR | 6 | HQ |

*Indicates extreme value.

Notes: References5 and20 had the same study population, but the follow-up time was different; thus the basic data in reference20 were not included in Table 1. This was similar for references44 and45, and references47,48, and46.

Values are mean±standard deviation or (range).

PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; N, number of samples; BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; BIVA, bioelectrical impedance vector analysis; ECWR: extracellular water ratio; PA, phase angle; hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac T troponin; NT–pro-BNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; OHI, overhydration index; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; LQ: low quality; HQ, high quality; TBW, total body water; ICW, intracellular water; ECW, extracellular water; NA, not available.

Qualitative analysis of included studies

Regarding dialysis methods, HD treatment was used in 31 of 55 studies and PD treatment in 16 studies; 4 studies used a combination of these two treatments. For the bioimpedance method, 18 of 55 studies reported the overhydration index (OHI) method, 16 studies the PA method, 11 studies the extracellular water expressed as a ratio (ECWR) method, 2 studies the bioimpedance vector analysis method, and 2 studies reported the OHI+ECWR method; only 1 study reported the PA+ECWR method and 1 study the N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide+high-sensitivity cardiac T troponin method.

Studies were divided into primary outcomes and secondary outcomes. Death was the primary outcome in 49 studies, CV events was the primary outcome in 1 study, and residual renal function was the primary outcome in 1 study. Secondary outcome events were reported in 20 articles, mainly CV death (8 articles), CV disease (6 articles), hospitalization events (2 articles), death (2 articles), hypertension (1 article), and technical failure (1 article).

Risk of mortality

There was no heterogeneity among two included studies;5,17 therefore, we used a fixed-effects model for the analysis (I2=0.0%). We found that an ECW/TBW ratio >0.4 was a significant risk factor for mortality, with HR (95% CI) 5.912 (2.016–17.342), P=0.001 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of overall meta-analysis.

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||

| ECW/TBW >0.4 | |||

| Overall | 5.912 (2.016–17.342) | 0.001 | 0.0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 5.912 (2.016–17.342) | ||

| ECW/ICW for every increase by 0.01 | |||

| Overall | 1.041 (1.031–1.051) | <0.001 | 45.7 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.041 (1.031–1.051) | ||

| 1-degree increase in PA | |||

| Overall | 0.676 (0.474–0.879) | <0.01 | 73.6 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.676 (0.474–0.879) | ||

| Dialysis method | |||

| HD | 0.749 (0.511–0.986) | <0.05 | 78.5 |

| PD | 0.488 (0.225–0.751) | <0.05 | 0.0 |

| Quality assessment | |||

| High quality | 0.686 (0.467–0.905) | <0.05 | 78.3 |

| Low quality | 0.560 (0.021–1.099) | >0.05 | NA |

| OH/ECW >15% | |||

| Overall | 2.722 (2.005–3.439) | <0.001 | 97.3 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 2.722 (2.005–3.439) | ||

| Dialysis method | |||

| HD | 2.265 (1.602–2.929) | <0.05 | 96.9 |

| PD | 7.820 (6.183–9.457) | <0.05 | NA |

| Quality assessment | |||

| High quality | 1.833 (1.259–2.407) | <0.05 | 90.7 |

| Low quality | 3.835 (2.548–5.122) | <0.05 | 92.7 |

| Cardiovascular events | |||

| ECW/TBW >0.4 | |||

| Overall | 2.679 (1.345–5.339) | 0.005 | 0.0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 2.679 (1.345–5.339) | ||

| ECW/ICW for every increase by 0.01 | |||

| Overall | 1.032 (1.017–1.047) | <0.001 | 49.2 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 1.032 (1.017–1.047) | ||

| 1-degree increase in PA | |||

| Overall | 0.736 (0.589–0.920) | 0.007 | 0.0 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 0.736 (0.589–0.920) |

OH, overhydration; TBW, total body water; ICW, intracellular water; ECW, extracellular water; PA, phase angle; PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; CI, confidence interval.

Two studies16,35 on ECW/ICW (per increment of 0.01) showed no remarkable heterogeneity (I2=45.7%). The result indicated that each 0.1-unit increase in the ECW/ICW ratio could independently predict the mortality risk: HR (95% CI) 1.041 (1.031–1.051), P<0.001 (Table 2).

Considerable heterogeneity was present after combining six studies13,14,19,24,25,37 (I2=73.6%); therefore, a random-effects model was used for the analysis. A 1-degree increase in PA was found to be a protective factor against death: HR (95% CI) 0.676 (0.474–0.879), P<0.01 (Table 2; Figure 2a). However, owing to the significant heterogeneity among the six studies, subgroup analysis was conducted for the dialysis method and quality assessment. In terms of dialysis method, a 1-degree increase in PA was associated with a reduced risk of death in patients receiving PD (HR 0.488, 95% CI: 0.225–0.751, P<0.05) and HD (HR 0.749, 95% CI: 0.511–0.986, P<0.05) treatment (Table 2; Figure 2b). The same result was observed in both the high-quality articles (HR 0.686, 95% CI: 0.467–0.905, P<0.05) and low-quality articles (HR 0.560, 95% CI: 0.021–1.099) (Table 2; Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of mortality among patients receiving dialysis with a 1-degree increase in phase angle. (a) Overall analysis; (b) subgroup analysis for dialysis method; (c) subgroup analysis for quality assessment.

TE, hazard ratio; seTE, standard error; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RRT, dialysis method; PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; HQ, high quality; LQ, low quality.

In eight studies,7,18,21,26,29,34,36,41 OH/ECW >15% was an independent risk factor for death: HR (95% CI): 2.722 (2.005–3.439), P<0.001 (Table 2; Figure 3a). A subgroup analysis was conducted for the dialysis method and quality assessment with large heterogeneity (I2=97.3%). Results of the subgroup analysis showed that OH/ECW >15% was closely related to the risk of death in patients undergoing HD (HR 2.265, 95% CI: 1.602–2.929, P<0.01) and PD (HR 7.820, 95% CI: 6.183–9.457, P<0.05) treatment (Table 2; Figure 3b). The same result was found for high-quality studies (HR 1.833, 95% CI: 1.259–2.407, P<0.05) and low-quality studies (HR 3.835, 95% CI: 2.548–5.122, P<0.05) (Table 2; Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of mortality among patients receiving dialysis with overhydration/extracellular water ratio >15% (a) overall analysis; (b) subgroup analysis for dialysis method; (c) subgroup analysis for quality assessment.

TE, hazard ratio; seTE, standard error; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RRT, dialysis method; PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; HQ, high quality; LQ, low quality.

Risk of CV events

There were two studies on ECW/TBW ratio >0.4,5,17 two studies on ECW/ICW (per increment of 0.01),16,35 and three studies on PA.13,14,31 Among them, ECW/TBW >0.4 (HR 2.679, 95% CI: 1.345–5.339, P=0.005) and every 0.01 unit increment in ECW/ICW ratio (HR 1.032, 95% CI: 1.017–1.047, P<0.001) were considered risk factors for CV events whereas a 1-degree increase in PA (HR 0.736, 95% CI: 0.589–0.920, P=0.007) emerged as a protective factor against CV events (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment

To determine the effect of individual studies on HRs, we carried out sensitivity analysis for each outcome. The results revealed that removing each study did not remarkably affect the overall HR, and the results of this meta-analysis were reliable and robust (Table 2). Additionally, there were fewer than nine studies included for each indicator in our study, which did not conform to the standard of publication bias.

Discussion

Recently, there has been increasing evidence that fluid overload is frequently present in a substantial number of patients receiving dialysis.6 More than one-third of incident patients undergoing dialysis, who are considered euvolemic or dehydrated on clinical assessment, have fluid overload using BIA measurement.4 Therefore, it is critical to make an accurate assessment of hydration status in this patient population. In our meta-analysis, four electronic databases were comprehensively searched to clarify the role of BI-OH markers in predicting the risk of mortality and CV events for patients receiving HD and PD. A total of 55 studies including 104,758 participants were identified. Among the BI-OH indices, ECW/TBW >0.4 and ECW/ICW (per increment of 10%) were found to be risk factors for mortality and CV events. Moreover, OH/ECW >15% was related to a reduced risk of death. Additionally, a 1-degree increase in PA emerged as a protective factor against mortality and CV events. All results suggested that multiple BI-OH parameters are associated with the risk of mortality and CV events, which may provide practical information to predict clinical outcomes among patients receiving dialysis.

Of note, there were various indices used to evaluate hydration status when using BIA to measure the risk of mortality. The ECW/TBW ratio was frequently used whereas OH/ECW and ECW/ICW were less frequently adopted. ECW/TBW ratios among patients were consistent, although the absolute values of ECW and TBW were different,9 thus leading to the wide use of ECW/TBW. Multiple studies showed that the ECW/TBW ratio as a risk factor independently predicted mortality.5,15,17 In 529 patients undergoing PD, O'Lone et al. found that this ratio as a continuous variable was not associated with increased mortality.40 Kang et al. conducted a retrospective study of 631 unselected incident patients on PD and concluded that a higher overload index (ECW/TBW >0.37) was associated with an increase in mortality;66 the ECW/TBW ratio showed a slightly significant difference. According to deviations from the normal value, a possible explanation may be patients’ nutritional status (including age and sex). The study by Shu et al.67 showed that ECW/ICW (per increment of 10%) remained a risk factor after adjusting obesity, age, sex, ethnicity, and other confounders, which would make the results more reliable and consistent with our results. PA level is calculated using BIA measurements as the arc tangent of the reactance-to-resistance ratio. Our results have been further confirmed in a previous study.12 A meta-analysis also indicated that a 1-degree decrease in PA level is considered a risk factor of mortality,12 indirectly suggesting results that are consistent with our results. In a single-center, retrospective study by Rhee et al. including 208 patients with acute kidney injury, a 1-degree increase in PA did not show any statistical significance in the prediction of in-hospital mortality (P>0.05).64 The reason may be related to the large number of studies included in our study and different study populations.

Another clinical outcome, CV events, can also occur in patients on dialysis. BI-OH indices are important predictors of their occurrence and development, which can serve to predict the risk of CV events. Prior studies have confirmed that every 0.1-unit increase in the ECW/ICW ratio and ECW/TBW >0.4 are risk factors for CV events, which is supported by Ng et al.15 In contrast to our results, CV events were found to be associated with PA in one study, mainly owing to a small number of patients and other confounding factors.14 PA cutoff values should be obtained for routine assessment and improving outcomes in patients receiving dialysis, but these outcomes were rarely determined in the included studies.

Our study has several strengths as follows. First, this meta-analysis included a considerable number of studies with large sample sizes (from 48 to 39,566), which may make our results more generalizable and reliable. Second, identical criteria were applied between studies in classifying BI-OH methods, which did not limit further meta-analyses and subgroup analyses for each hydration indicator. The main limitation of our meta-analysis was the absence of publication bias. The reason may be the inclusion of fewer than 9 studies for each indicator in our study, which does not conform to the standard of publication bias. Unadjusted HRs were used in our cohort studies, which may be a source of bias.

Conclusions

Our results showed that ECW/TBW >0.4, ECW/ICW (per each 0.1-unit increase), and OH/ECW >15% were risk factors for mortality in patients receiving dialysis. ECW/TBW >0.4 and ECW/ICW (per increment of 10%) were associated with an increased risk of CV events; a 1-degree increase in PA was a protective factor against mortality and CV events.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605211031063 for Effect of bioimpedance-defined overhydration parameters on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yajie Wang and Zejuan Gu in Journal of International Medical Research

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-imr-10.1177_03000605211031063 for Effect of bioimpedance-defined overhydration parameters on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yajie Wang and Zejuan Gu in Journal of International Medical Research

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This work was supported by the Project of “Nursing Science” Funded by the Priority Discipline Development Program of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (General Office, the People’s Government of Jiangsu Province [2018] No. 87), and grants from the Jiangsu Provincial Medical Innovation Team (CXTDA2017019).

ORCID iD: Zejuan Gu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2357-3867

References

- 1.Himmelfarb J, Vanholder R, Mehrotra R, et al. The current and future landscape of dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020; 16: 573–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanderson KR, Harshman LA.Renal replacement therapies for infants and children in the ICU. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020; 32: 360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2019: S0272-6386(19)31008-X. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronco C, Verger C, Crepaldi C, et al. Baseline hydration status in incident peritoneal dialysis patients: the initiative of patient outcomes in dialysis (IPOD-PD study)†. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Q, Lin J, Li J, et al. The Effect of Fluid Overload on Clinical Outcome in Southern Chinese Patients Undergoing Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2015; 35: 691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwan BC, Szeto CC, Chow KM, et al. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for the detection of fluid overload in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2014; 34: 409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazot C, Wabel P, Chamney P, et al. Importance of normohydration for the long-term survival of haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 2404–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Der Sande FM, Van De Wal-Visscher ER, Stuard S, et al. Using Bioimpedance Spectroscopy to Assess Volume Status in Dialysis Patients. Blood Purif 2020; 49: 178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies SJ, Davenport A.The role of bioimpedance and biomarkers in helping to aid clinical decision-making of volume assessments in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2014; 86: 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper BA, Aslani A, Ryan M, et al. Comparing different methods of assessing body composition in end-stage renal failure. Kidney Int 2000; 58: 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffrin MY, Morel H.Body fluid volumes measurements by impedance: A review of bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) and bioimpedance analysis (BIA) methods. Med Eng Phys 2008; 30: 1257–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabinor M, Elphick E, Dudson M, et al. Bioimpedance-defined overhydration predicts survival in end stage kidney failure (ESKF): systematic review and subgroup meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang R, Wu M, Wu H, et al. Lower Phase Angle Measured by Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Is a Marker for Increased Mortality in Incident Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. J Ren Nutr 2020; 30: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin JH, Kim CR, Park KH, et al. Predicting clinical outcomes using phase angle as assessed by bioelectrical impedance analysis in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Nutrition 2017; 41: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng JK, Kwan BC, Chow KM, et al. Asymptomatic fluid overload predicts survival and cardiovascular event in incident Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0202203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yajima T, Yajima K, Takahashi H, et al. Combined Predictive Value of Extracellular Fluid/Intracellular Fluid Ratio and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index for Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Nutrients 2019; 11: 2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim CR, Shin JH, Hwang JH, et al. Monitoring Volume Status Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. ASAIO J 2018; 64: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoccali C, Moissl U, Chazot C, et al. Chronic Fluid Overload and Mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 2491–2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee H, Baek MJ, Chung HC, et al. Extracellular volume expansion and the preservation of residual renal function in Korean peritoneal dialysis patients: a long-term follow up study. Clin Exp Nephrol 2016; 20: 778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Q, Yi C, Li J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of fluid overload in Southern Chinese continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wizemann V, Wabel P, Chamney P, et al. The mortality risk of overhydration in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24: 1574–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abad S, Sotomayor G, Vega A, et al. The phase angle of the electrical impedance is a predictor of long-term survival in dialysis patients. Nefrologia 2011; 31: 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avram MM, Fein PA, Rafiq MA, et al. Malnutrition and inflammation as predictors of mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2006; 70: S4–S7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beberashvili I, Azar A, Sinuani I, et al. Longitudinal changes in bioimpedance phase angle reflect inverse changes in serum IL-6 levels in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Nutrition 2014; 30: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beberashvili I, Azar A, Sinuani I, et al. Bioimpedance phase angle predicts muscle function, quality of life and clinical outcome in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014; 68: 683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caetano C, Valente A, Oliveira T, et al. Body Composition and Mortality Predictors in Hemodialysis Patients. J Ren Nutr 2016; 26: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Guo LJ, Wang T.Extracellular water/intracellular water is a strong predictor of patient survival in incident peritoneal dialysis patients. Blood Purif 2007; 25: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Araujo Antunes A, Vannini FD, De Arruda Silveira LV, et al. Associations between bioelectrical impedance parameters and cardiovascular events in chronic dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2013; 45: 1397–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekker MJE, Marcelli D, Canaud BJ, et al. Impact of fluid status and inflammation and their interaction on survival: a study in an international hemodialysis patient cohort. Kidney Int 2017; 91: 1214–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demirci C, Asci G, Demirci MS, et al. Impedance ratio: a novel marker and a powerful predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2016; 48: 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan S, Davenport A.The importance of overhydration in determining peritoneal dialysis technique failure and patient survival in anuric patients. Int J Artif Organs 2015; 38: 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiedler R, Jehle PM, Osten B, et al. Clinical nutrition scores are superior for the prognosis of haemodialysis patients compared to lab markers and bioelectrical impedance. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24: 3812–3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoppe K, Schwermer K, Klysz P, et al. Cardiac Troponin T and Hydration Status as Prognostic Markers in Hemodialysis Patients. Blood Purif 2015; 40: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jotterand Drepper V, Kihm LP, Kalble F, et al. Overhydration Is a Strong Predictor of Mortality in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients - Independently of Cardiac Failure. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim EJ, Choi MJ, Lee JH, et al. Extracellular Fluid/Intracellular Fluid Volume Ratio as a Novel Risk Indicator for All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in Hemodialysis Patients. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0170272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YJ, Jeon HJ, Kim YH, et al. Overhydration measured by bioimpedance analysis and the survival of patients on maintenance hemodialysis: a single-center study. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2015; 34: 212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koh KH, Wong HS, Go KW, et al. Normalized bioimpedance indices are better predictors of outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31: 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathew S, Abraham G, Vijayan M, et al. Body composition monitoring and nutrition in maintenance hemodialysis and CAPD patients–a multicenter longitudinal study. Ren Fail 2015; 37: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oei E, Paudel K, Visser A, et al. Is overhydration in peritoneal dialysis patients associated with cardiac mortality that might be reversible? World J Nephrol 2016; 5: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Lone EL, Visser A, Finney H, et al. Clinical significance of multi-frequency bioimpedance spectroscopy in peritoneal dialysis patients: independent predictor of patient survival. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 1430–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onofriescu M, Siriopol D, Voroneanu L, et al. Overhydration, Cardiac Function and Survival in Hemodialysis Patients. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paniagua R, Ventura MD, Avila-Diaz M, et al. NT-proBNP, fluid volume overload and dialysis modality are independent predictors of mortality in ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paudel K, Visser A, Burke S, et al. Can Bioimpedance Measurements of Lean and Fat Tissue Mass Replace Subjective Global Assessments in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients? J Ren Nutr 2015; 25: 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segall L, Mardare NG, Ungureanu S, et al. Nutritional status evaluation and survival in haemodialysis patients in one centre from Romania. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24: 2536–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segall L, Moscalu M, Hogas S, et al. Protein-energy wasting, as well as overweight and obesity, is a long-term risk factor for mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2014; 46: 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siriopol D, Hogas S, Voroneanu L, et al. Predicting mortality in haemodialysis patients: a comparison between lung ultrasonography, bioimpedance data and echocardiography parameters. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28: 2851–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siriopol D, Voroneanu L, Hogas S, et al. Bioimpedance analysis versus lung ultrasonography for optimal risk prediction in hemodialysis patients. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 32: 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siriopol I, Siriopol D, Voroneanu L, et al. Predictive abilities of baseline measurements of fluid overload, assessed by bioimpedance spectroscopy and serum N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, for mortality in hemodialysis patients. Arch Med Sci 2017; 13: 1121–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tangvoraphonkchai K, Davenport A.Pre-dialysis and post-dialysis hydration status and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and survival in haemodialysis patients. Int J Artif Organs 2016; 39: 282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian JP, Wang H, Du FH, et al. The standard deviation of extracellular water/intracellular water is associated with all-cause mortality and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 2016; 48: 1547–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chertow GM, Johansen KL, Lew N, et al. Vintage, nutritional status, and survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2000; 57: 1176–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Iorio B, Cillo N, Cirillo M, et al. Charlson Comorbidity Index is a predictor of outcomes in incident hemodialysis patients and correlates with phase angle and hospitalization. Int J Artif Organs 2004; 27: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fein P, Chattopadhyay J, Paluch MM, et al. Enrollment fluid status is independently associated with long-term survival of peritoneal dialysis patients. Adv Perit Dial 2008; 24: 79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maggiore Q, Nigrelli S, Ciccarelli C, et al. Nutritional and prognostic correlates of bioimpedance indexes in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 2103–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pillon L, Piccoli A, Lowrie EG, et al. Vector length as a proxy for the adequacy of ultrafiltration in hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 1266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pupim LB, Caglar K, Hakim RM, et al. Uremic malnutrition is a predictor of death independent of inflammatory status. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 2054–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arrigo M, Von Moos S, Gerritsen K, et al. Soluble CD146 and B-type natriuretic peptide dissect overhydration into functional components of prognostic relevance in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: 2035–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avram MM, Fein PA, Borawski C, et al. Extracellular mass/body cell mass ratio is an independent predictor of survival in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int Suppl 2010; 117: S37–S40. PMID: 20671743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bansal N, Zelnick LR, Himmelfarb J, et al. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Measures and Clinical Outcomes in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 72: 662–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beberashvili I, Azar A, Sinuani I, et al. Objective Score of Nutrition on Dialysis (OSND) as an alternative for the malnutrition-inflammation score in assessment of nutritional risk of haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 2662–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hecking M, Moissl U, Genser B, et al. Greater fluid overload and lower interdialytic weight gain are independently associated with mortality in a large international hemodialysis population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: 1832–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang JC, Tsai YC, Wu PY, et al. Independent Association of Overhydration with All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Adjusted for Global Left Ventricular Longitudinal Systolic Strain and E/E' Ratio in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Blood Press Res 2018; 43: 1322–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mushnick R, Fein PA, Mittman N, et al. Relationship of bioelectrical impedance parameters to nutrition and survival in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int Suppl 2003; 87: S53–S56. PMID: 14531774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhee H, Jang KS, Shin MJ, et al. Use of Multifrequency Bioimpedance Analysis in Male Patients with Acute Kidney Injury Who Are Undergoing Continuous Veno-Venous Hemodiafiltration. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0133199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voroneanu L, Siriopol D, Nistor I, et al. Superior predictive value for NTproBNP compared with high sensitivity cTnT in dialysis patients: a pilot prospective observational study. Kidney Blood Press Res 2014; 39: 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang SH, Choi EW, Park JW, et al. Clinical Significance of the Edema Index in Incident Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0147070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shu Y, Liu J, Zeng X, et al. The Effect of Overhydration on Mortality and Technique Failure Among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Blood Purif 2018; 46: 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605211031063 for Effect of bioimpedance-defined overhydration parameters on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yajie Wang and Zejuan Gu in Journal of International Medical Research

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-imr-10.1177_03000605211031063 for Effect of bioimpedance-defined overhydration parameters on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yajie Wang and Zejuan Gu in Journal of International Medical Research