Abstract

Introduction

Understanding costs of care for people dying with dementia is essential to guide service development, but information has not been systematically reviewed. We aimed to understand (1) which cost components have been measured in studies reporting the costs of care in people with dementia approaching the end of life, (2) what the costs are and how they change closer to death, and (3) which factors are associated with these costs.

Methods

We searched the electronic databases CINAHL, Medline, Cochrane, Web of Science, EconLit, and Embase and reference lists of included studies. We included any type of study published between 1999 and 2019, in any language, reporting primary data on costs of health care in individuals with dementia approaching the end of life. Two independent reviewers screened all full‐text articles. We used the Evers' Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist to appraise the risk of bias of included studies.

Results

We identified 2843 articles after removing duplicates; 19 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 16 were from the United States. Only two studies measured informal costs including out‐of‐pocket expenses and informal caregiving. The monthly total direct cost of care rose toward death, from $1787 to $2999 USD in the last 12 months, to $4570 to $11921 USD in the last month of life. Female sex, Black ethnicity, higher educational background, more comorbidities, and greater cognitive impairment were associated with higher costs.

Discussion

Costs of dementia care rise closer to death. Informal costs of care are high but infrequently included in analyses. Research exploring the costs of care for people with dementia by proximity to death, including informal care costs and from outside the United States, is urgently needed.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cost of care, cost of illness, dementia, end‐of‐life, health care cost, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is currently the fifth leading cause of death globally,1 and the number of people dying with dementia in the world is projected to increase from ≈2 million deaths in 2016 to more than 7 million in 2060.2 When approaching death, people with dementia experience a rapid increase in the incidence of fatigue, pain, and dizziness;3 potentially burdensome hospital admissions;4 and emergency department visits.5

Assessing the economic impact of illness on society is key to understanding resource needs, identifying main cost components, explaining the variability of costs, and identifying management pathways to inform policy.6 Two published systematic reviews have examined aspects of dementia care costs, including hospital, outpatient, drugs, informal, and indirect costs.7, 8 In Quentin et al., direct and indirect costs for patients with severe dementia were almost twice the costs for people with mild dementia.7 In Schaller et al., the main drivers of total dementia costs were nursing home expenditures and informal costs due to home‐based care.8 Neither systematic review examined end‐of‐life care costs.

Understanding the costs of care at the end of life is particularly important as health‐care costs have been shown to increase by proximity to death.9 A systematic review of studies exploring the cost of caregiving among people receiving palliative care at the end of life found informal caregiving could account for 27% to 80% of total costs and have a significant impact on families and carers.10 Unlike the cost of dementia care, the evidence on costs of care approaching the end of life is not well understood.

We aimed to understand the costs of care for people with dementia approaching the end of life by answering the following questions:

Which cost components have been measured in studies reporting the costs of care in people with dementia approaching the end of life?

What are the costs of care for people with dementia approaching the end of life and how do these change closer to death?

Which factors are associated with the costs of care among people with dementia approaching the end of life?

2. METHODS

We undertook a systematic review of primary studies reporting costs of care for people with dementia approaching the end of life. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42020166337).

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: We reviewed the literature using MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Web of Science, and EconLit. While the cost of dementia care has been reported and analyzed, evidence regarding the costs of health‐care at the end of life are not well understood.

Interpretation: We found that direct costs of care in people with dementia are high and increase considerably toward death. Long‐term facility and hospice care costs were among the highest direct cost components. Informal costs of care represent a substantial component of total costs but have been rarely measured, and there is little information from countries outside the United States.

Future directions: The article proposes a summary of factors contributing to the variability of the cost of care in this population and unveils the need for a better understanding of informal care cost for dementia care at the end of life.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they reported direct or informal health‐care costs for individuals who died with dementia (for retrospective studies) or who are likely to be approaching the end of life based on clinical prognosis, such as “patients with severe dementia” or “patients with dementia who are thought to be in the last year of life” (for prospective studies). Studies that included individuals with different conditions were included only if results for people with dementia were reported separately. Any type of study reporting primary data on costs of care was considered, including both incidence and prevalence‐based analyses. We did not include modeling studies that empirically estimated costs of care unless based on primary data. We included only articles published between 1999 and 2019 in recognition that articles published before this time are unlikely to have financial relevance today. Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study |

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Language |

|

|

| Years |

|

2.2. Information sources

We searched the electronic databases CINAHL, Medline, Cochrane, Web of Science, EconLit, and Embase and reference lists of included studies from January 1999 to December 2019. Additional references were retrieved through informal searches on Google and consultations with a health‐care economist (DY).

2.3. Search strategy

The search strategy included the concepts of “dementia,” “end of life,” and “health‐care costs.” Medical subject headings (MeSH) index terms were used together with free text to capture relevant articles. The terms recommended by the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group for dementia were used. The complete search strategy is available in Table S1 in supporting information.

2.4. Selection process

The study selection and de‐duplication processes were managed in EndNote X8. Two reviewers (JL, TS) double‐screened 20% of retrieved titles and abstracts and excluded irrelevant articles, reaching a 92.2% agreement and an inter‐rater agreement of k = 0.65 (P < .001) after the blind assessment and before discussion. Discrepancies were solved by discussion. One reviewer (JL) screened the remaining titles and abstracts. Two independent reviewers (JL, with either LT or EY) screened all full‐text articles to determine eligibility. Discrepancies were solved by discussion or the inclusion of a third reviewer (KS, DY) in case no agreement was reached.

2.5. Risk of bias in individual studies

The methodological quality of included articles was assessed using the Evers’ Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) checklist.11, 12 One reviewer (JL) assessed all included studies and discussed scores with a second reviewer (DY). Studies were not excluded based on quality appraisal results, as one of our aims was to understand the breadth of studies describing costs of care at the end of life.

2.6. Data analysis

A data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel (version 2101), piloted, and used (Table S2 in supporting information). Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer (JL) and checked by a second (DY, RC).

For question 1, the type of cost components extracted for all included studies was summarized in a table by one reviewer (JL) and discussed with three others (KS, IH, DY).

For question 2, to describe costs of care in people with dementia at the end of life, we used the average cost per person reported for the end‐of‐life period considered in each study. When studies reported estimates for populations with different diagnoses, we used only costs for people with dementia. When studies reported separate estimates for different groups of people with dementia (for instance, people with dementia living in care homes and those not living in care homes), we calculated a weighted mean based on sample numbers. When costs were reported by components of care, we calculated the cost by adding the separated means. All costs were inflated and converted to 2019 US dollars (USD) using purchasing power parities (PPP) conversion rates provided by the World Bank.13 To make costs more comparable across studies, we calculated the mean costs per person per month for each study ( = the mean costs per person/the study period [in months] considered). We classified studies according to whether they measured direct costs, informal costs, or both. Costs of care were defined according to Gardiner et al. (Table 2).14 We report both the average costs per person for the entire end‐of‐life period considered in the study, and the estimated average costs per month. One reviewer (JL) performed the analysis; tables and results were discussed and checked by three other reviewers (KS, DY, IH).

TABLE 2.

Definitions of types of health‐care costs used, based on Gardiner et al.14

|

For question 3, studies were grouped based on whether they reported sociodemographic, illness‐related, or health‐care service‐related factors associated with the cost of care for people with dementia at the end of life. A preliminary descriptive paragraph on each study was produced by one reviewer (JL) and discussed with three other reviewers (KS, IH, DY). A summary of the main points was then agreed.15

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

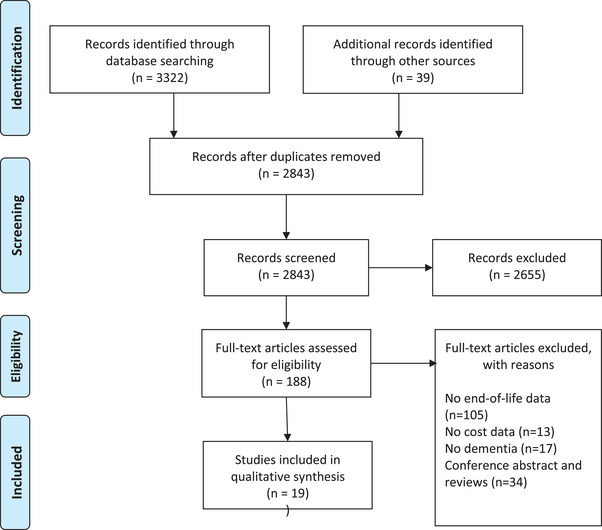

After removing duplicates, 2843 articles were retrieved from databases and hand searches. One hundred eighty‐eight articles were included for full‐text screening; 19 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were considered for the analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flow diagram

Of the 19 included articles, 16 were from the United States,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 two were from Europe (United Kingdom and the Netherlands),32, 33 and one from Australia.34 Twelve (75.0%) included studies had a retrospective design.16, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 31, 33, 34 All but one study identified costs from claims records,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 while one study used questionnaires.21 Studies focused on different end‐of‐life periods, ranging from the last month of life to 60 months before death. Three studies included people with Alzheimer's disease (AD) only,21, 28, 34 and the other 16 included people with any type of dementia diagnosis.

3.2. Quality appraisal of included studies

The mean quality score of all included studies on the CHEC checklist was 82.8% (proportion of “yes” answers). The lowest score was 64.3% and 12 studies scored more than 80% (Table S3 in supporting information). The most common source of poor quality was the lack of an explicit mention of the economical perspective (such as government, insurers, patients, or societal) in 16 studies and the absence of an appropriate discussion regarding ethical and distributional issues in eight studies.

3.3. Question 1: Which cost components have been measured in studies reporting the costs of care in people with dementia approaching the end of life?

Types of costs measured included hospital, community care, hospice, long‐term care facility (nursing or residential home) expenses and informal costs (Table 3). Of the 19 included articles, 16 included in‐hospital, out‐of‐hospital, community, and hospice care expenses paid by insurance companies. Three studies also included long‐term care facility expenses.25, 32, 33 Two of the included studies only reported hospital costs, including in‐hospital17, 34 and emergency department expenses.17 Two studies measured informal costs,21, 22 and only one of these included the informal costs as a proportion of the total costs of care.22

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of included studies and information regarding total cost

| Total costs | What is included in the total costs | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Country | Study design | Age | Type of dementia diagnosis | Sex (% female) | Ethnicity | Residency | Cost perspective | Number of people with dementia | Description | End‐of‐life period (months) | Mean for total end‐of‐life period (USD 2019) | Mean by month (USD 2019) | In‐hospital care | ED visits | Outpatient | Community care | Long‐term care facility | Hospice | informal care | Out‐of‐pocket |

| Studies including only direct costs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lamb VL., 2008 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >85: 37.5% (5 years BD) | ADRD | 65.0% | White 89.8% | Nursing home 30.2% | Not reported | 2449 | Medicare expenditure difference between people with and without dementia from claim records | 60 | 7587.1‡ | – | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Ornstein KA., 2018 | USA | Prospective cohort study | mean 88.8 | ADRD | 67.4% | White 30.23% | Not reported | Not reported | 86 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | 36 (Survival time 3.02 years) | 159397.9 | 4427.7 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Goldfeld KS., 2011 | USA | Prospective cohort study | mean 85.3 (SD 7.5)* | ADRD | 85.5%* | White 89.5%* | Nursing home 100% | Not reported | 177 | Total expenditures (use from clinical records and costs estimated from Medicare services information) | 18 | 8751.7 | 486.2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| McCormick WC., 2001 | USA | Case control study | mean 84.3 (SD 6.8) | ADRD | 52.6% | White 91.0% | Not reported | Not reported | 396 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | 12 | 21448.7 | 1787.4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Gozalo P., 2015 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | mean 85.6* | ADRD | 64.0%* | White 88.2%* | Nursing home 100% | Not reported | 162459 | Total Medicare and Medicaid expenditures pp from claim records | 12 | 32494.1 | 2707.8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Zhu CW., 2017 | USA | Prospective cohort study | mean 85.3 (SD 7.1) | ADRD | 85.7% | White 14.3% | Not reported | Not reported | 49† | Total Medicare expenditures pp from claim records | 12 | 21884.6 | 1823.7 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Daras LC., 2017 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >85: 36.5%* | ADRD | 55.1%* | White 86.2% | Nursing home 19.9% | Not reported | 1426 | Medicare payments for outpatient, ED visits and hospitalizations from interviews and claim records | 12 | 21879.5 | 1823.3 | √ | √ | ||||||

| van der Plas AG., 2017 | NDL | Retrospective cohort study | mean 86.1 (SD 6.9) | ADRD | 67.6% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 3586 | Total cost from billed insurance costs (Hospitals use, out‐of‐hospital, home care, care homes and nursing homes) | 12 | 35985.3 | 2998.8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Spilsbury K., 2017 | AUS | Retrospective cohort study | >80: 46.5%* | AD | 45.9%* | Not reported | Nursing home 21.2%* | Government perspective | 605 | Crude cohort averaged hospital cost per day x4.7 days in the last 12 months of life from claim records | 12 | 62.1 | – | √ | |||||||

| Pyenson B., 2019 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | mean 86.2 | ADRD | 65.4% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 131855 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | 12 | 34760.2 | 2896.7 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Pyenson B., 2004 | USA | Prospective cohort study | >85%: 13.4%* | AD | 46.5%* | not reported | Not clear | Not reported | 151 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | mean days 183.8 | 46300.9 | 7716.8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Sampson E., 2012 | UK | Other | 64 to 84 years | ADRD | 33.3% | White 88.9% | Nursing home 11.1% | Societal perspective | 9 | Total expenditures (use from clinical records and interviews and costs estimated from NHS services information) | 6 | 23597.8 | 3933.0 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Nicholas LH., 2014 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | mean 84.8 | ADRD | 59.8% | White 72.7% | Nursing home 56.2% | Not reported | 2509 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | 6 | 34000.7 | 5666.8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Zuckerman RB., 2016 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >85: 59.9% | ADRD | 69.2% | White 85.4% | Nursing home 56.9% | Not reported | 244674 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records | 6 | 42395.9 | 7066.0 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Crouch E., 2019 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >85: 61.7% | ADRD | 69.0% | White 85.2% | Not reported | Not reported | 7895 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records among those with an expenditure. | 6 | 24483.8 | 4080.6 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Miller SC., 2004 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | mean 85.9 (SD 7.1) | ADRD | Not reported | Not reported | Nursing home 100% | Not reported | 2558 | Total Medicare and Medicaid expenditures from claim records | 1 | 11920.9 | 11920.9 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Gozalo PL, 2008 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | >85: 55.7%* | ADRD | 70.7%* | White 79.4%* | Nursing home 100% | Not reported | 2556 | Total Medicare and Medicaid expenditures from claim records | 1 | 11914.2 | 11914.2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| van der Plas AG., 2017 | NDL | Retrospective cohort study | mean 86.1 (SD 6.9) | ADRD | 67.6% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 3586 | Total cost from billed insurance costs (Hospitals use, out‐of‐hospital, home care, care homes and nursing homes) | 1 | 4570.3 | 4570.3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Studies including only informal costs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kelley AS., 2013 | USA | Prospective cohort study | mean 84.3 (SD 7.6)* | AD | 57.0%* | White 78.8% | Nursing home 21.2%* | Not reported | 651 | Health‐care out‐of‐pocket expenditures from interviews (insurance, hospital, physician, medication, nursing home, hired helpers, in‐home medical care and other expenses) | 60 | 80118.5 | 1335.3 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Studies including both direct and informal costs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kelley AS., 2015 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | Mean 88.4 (SD 6.4) | ADRD | 68.1% | Non‐Black 87.0% | Not reported | Societal perspective | 555 | Total Medicare expenditures from claim records + Health‐care out‐of‐pocket expenditures from interviews (insurance, hospital, physician, medication, nursing home, hired helpers, in‐home medical care, and other expenses) | 60 | 335966.3 | 5599.4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADRD, Alzheimer's disease and related dementias; AUS, Australia; ED, emergency department; NDL, Netherlands; SD, standard deviation; pp, per person; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States; USD, US dollars.

* Data available for the whole sample and not specific for dementia patients.

† Only including severe dementia because the % of decedents in that cohort > 50%.

‡ Total costs for people with dementia USD$7587.1 more than people without dementia.

? The paper is not clear regarding whether hospice care costs were considered.

Only two studies analyzed the proportion of the total cost of care explained by each cost component. In Goldfeld et al., hospice expenditures accounted for 45.7% of total costs, followed by in‐patient (33.2%) and primary care provider expenditures (9.7%).18 In van der Plas et al., the highest cost component in the last year of life was nursing home expenses.33 Neither of these two studies included informal costs among the cost components analyzed.

3.4. Question 2: What are the costs of care for people with dementia approaching the end of life and how do these change closer to death?

3.4.1. Studies including only direct costs

Seventeen studies included only direct costs. Three of them reported costs of care for an end‐of‐life period longer than the last 12 months,18, 23, 27 seven reported costs of care for the last 12 months,17, 19, 24, 29, 30, 33, 34 five for the last 6 months,16, 25, 26, 31, 32 and three for the last month of life.20, 25, 33 All 17 studies measured hospital and emergency department costs and all but two included out‐patient expenses and community care. Thirteen of 17 studies included hospice expenses,16, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and three included long‐term care facility costs.25, 32, 33

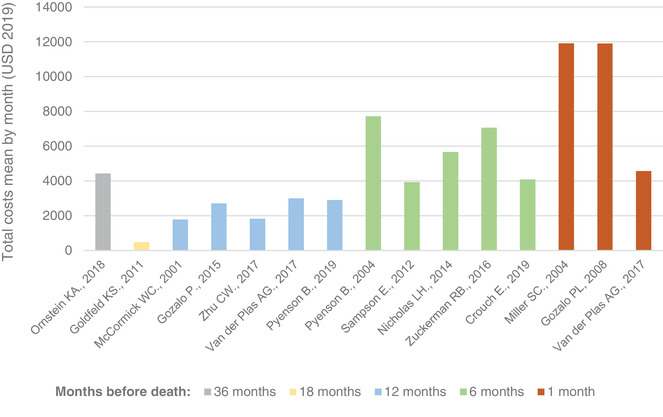

The derived monthly cost was higher in studies reporting costs in the last six or one month of life compared to those reporting costs for a longer end‐of‐life period (Figure 2). Derived monthly costs varied from $486 to $4428 USD for the final 18 to 36 months of life, $1787 to $2999 USD for the last 12 months of life, $3933 to $7717 USD for the last 6 months, and $4570 to $11921 USD for the last month of life.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of monthly derived costs of care in studies including only direct costs of care by end‐of‐life period considered. USD, US dollars

3.4.2. Studies including only informal costs

One study explored out‐of‐pocket expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries over the last 5 years of life. Monthly derived out‐of‐pocket expenses among people with AD and other dementias was $1335 USD on average and out‐of‐pocket payments for long‐term care facilities accounted for 56% of the average family spending.21

3.4.3. Studies including direct and informal costs

Only one study considered both direct and informal costs in the total cost of care.22 In this study the estimated total cost of care in the last 5 years of life among individuals with dementia was $5599 USD per month.22

3.5. Question 3: Which factors are associated with the costs of care of people with dementia approaching the end of life?

Among the factors explaining the variance in the cost of care were sociodemographic characteristics, illness‐related factors such as comorbidity or type of dementia diagnosis, and health‐care service‐related factors, such as the use of particular health‐care services or places of care.

3.5.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

Three studies explored the association between costs of dementia care and sociodemographic characteristics. Ornstein et al. examined differences in total Medicare expenditures among people with dementia from diagnosis to death by ethnicity.27 Non‐Hispanic Black people had a 41% higher spending compared to non‐Hispanic White people from time of diagnosis to death, but the difference was not significant after adjusting for confounding. In Kelley et al., total cost of care among people with dementia in the last 5 years of life were significantly higher for people older than 90 years (vs. 70–74 years old), Black (vs. White), women, married (vs. not married), and with higher than high school education (vs. less than high school).22 In Goldfeld et al., younger ages and not living in a special care dementia unit were independently associated with higher costs in the last 90 days of life.18

3.5.2. Illness‐related factors

Three studies explored the association among dementia severity, comorbidities, and cost of care at the end of life.18, 22, 30 In Kelley et al., people with dementia and a history of stroke, diabetes, heart disease, or psychological conditions had higher total costs in the last 5 years of life.22 In Zhu et al., total Medicare expenditures in people with severe dementia were approximately 10 times higher among those with more than three comorbidities versus no comorbidities.30 In Goldfeld et al., people with more severe cognitive impairment, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and a prior history of acute illness had higher total costs during the last 90 days of life.18

Seven studies explored differences in health‐care costs between individuals with and without dementia or other conditions.16, 17, 22, 23, 24, 29, 34 Two of them only included hospital costs in the analysis.17, 34 In Daras et al.17 and Spilsbury and Rosenwax,34 hospital costs in the last 12 months of life were lower for patients with dementia than patients with non‐dementia or cancer diagnosis, respectively. When only direct costs of care were considered, the costs of care for people with dementia were higher than for those without dementia in the last 6 months,16 12 months,24, 29 and nonsignificant in one study in the last 5 years of life.23 When both informal and direct costs were considered, the cost of care was higher for those with dementia than for those without dementia.22

We found three studies exploring the cost of dementia care by proximity to death. In Pyenson et al., Medicare costs for people with AD and general dementia in the last year of life was three times higher than 8 years before death.29 In McCormick et al., costs tended to escalate in the last 3 months of life.24 In Goldfeld et al., total mean Medicare expenditures increased by 65% by periods of 3 months in the last year of life.18

3.5.3. Health‐care service‐related factors

Health‐care service factors examined among studies included place of care and the use of hospice services.

One study analyzed differences in total Medicare costs by place of care. Patients with mild dementia living in the community had significantly lower costs in the last 6 months of life than those living in a nursing home. However, for people with severe dementia this relationship was reversed.26

Five studies explored differences in costs for people with dementia who used hospice services, and found mixed results.19, 20, 25, 28, 31

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review to examine costs of care for people with dementia approaching the end of life. The review found that costs of care in people with dementia are high and tend to increase toward death. There was a large variation in costs of care across studies. Long‐term care facility and informal care costs were among the highest cost components. Only two studies included informal costs of care and most studies were from the United States. Non‐White ethnicity, female sex, married status, higher education level, more severe dementia, and higher number of comorbidities were associated with higher costs.

We found a dearth of information on informal costs. A systematic review exploring the financial impact of caring for people at the end of life shows that informal costs are substantial, and have an important impact on caregiver burden.10 In Kelley et al., out‐of‐pocket expenditures were a large proportion of the total cost of care in the last 5 years of life in decedents with dementia in the United States.22 Studies considering only Medicare expenditures show the costs of care at the end of life for people with dementia appeared to be lower than for other conditions,16, 17, 24, 29, 34 probably explained by lower rates of hospital admissions.35, 36 In contrast, when including informal costs, the costs were substantially higher for individuals with dementia.22 Informal costs may be particularly relevant among people with dementia as their needs for formal and informal care are higher than people dying with other conditions.36, 37 Therefore, studies that do not account for informal costs are likely to greatly underestimate total costs of care for people dying with dementia.

Our results show that monthly derived costs tend to increase in the last months of life, which is consistent with results from the three individual studies included that directly explored costs by proximity to death,18, 24, 29 and with findings from studies in other conditions.9 This could reflect an increase in health‐care needs due to a rise in symptom burden among people with dementia close to death,3 and is also consistent with studies that have found an increase in potentially avoidable hospital admissions4 and emergency department visits5 among these patients closer to death. Further research is needed to explore more directly how costs increase toward the end of life, and to understand the extent to which this represents low‐value care.

In this review there were differences in the end‐of‐life period and types of cost components considered in each study, making comparisons between studies challenging. Some of these differences are likely to be explained by disparities among health‐care systems, or changes of costs over time that are not addressed by adjusting for inflation. Factors identified as contributing to the variability of the costs reported include (1) those related to the study design, (2) those related to the study population, and (3) the type of costs considered (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Factors contributing to the variability of the total cost of care across studies

|

4.1. Implications for policy and research

This review exposes the urgent need for studies describing and analyzing the cost of care at the end of life for people with dementia, in particular for costs outside the United States and informal care costs. This is not exempt of challenge. The lack of evidence in informal care costs may reflect important barriers in quantifying and analyzing informal care, such as difficulties measuring and valuing the time of caregiving.38, 39

Understanding how cost components change toward the end of life is needed to plan effective use of health‐care services.40 We found no studies directly exploring how the different cost components change by proximity to death. van der Plas et al. found long‐term care facilities contribute proportionally more to the total cost of care in the last month of life compared to the last 360 days.33 More studies exploring how different cost components change by proximity to death, and the extent to which these costs are modifiable, are needed.

Translating evidence from studies on end‐of‐life care costs into improved clinical services relies on prospective identification of the period before death. This is particularly challenging for people with dementia due to communication difficulties and the pattern of slow decline.41, 42 Nevertheless, ≈47% of older adults who died have a record indicating their general practitioner recognized they were close to death,43 and identification of palliative care needs in patients with dementia has been associated with lower chances of multiple hospital admissions in their last 90 days of life.44 Whether better recognition of the end of life among people with dementia could help reduce costs and which types of costs could be an important question to address.

Factors associated with costs of care for people with dementia at the end of life have been poorly studied. There is a need to explore the variability of total costs explained by factors such as ethnicity or level of deprivation to address potential inequities in health‐care access at the end of life.

There is evidence suggesting informal costs are high for people with dementia approaching the end of life. Governments should make efforts to address the economic burden that dementia care places on patients’ families, especially considering the large number of people projected to be affected in the next 40 years. Higher social care expenditure has been associated with fewer hospital readmissions, reduced length of stay, and lower expenditure on secondary health‐care services.45 Informal care use has been shown to be endogenous and a substitute of formal care received at home by older people.46 However, this tends to disappear as the level of disability of the older person increases and it is not necessarily a substitute for care received in a long‐term care facility or other health‐care service.47, 48 Future research needs to investigate the effects of hospital costs on economic burden on family and the reciprocal relationship between informal care and total care costs

4.2. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on costs of care for individuals with dementia with a focus on the end of life. While other articles have analyzed the cost of care by dementia stage,7 the severity of the disease is not necessarily representative of a terminal stage, as only 25% of people who die with dementia are at the severe stage of the illness.49

This study has limitations. The heterogeneity in end‐of‐life periods and cost components considered by studies limited the options for analysis. Only 20% of all titles and abstracts were double‐screened, though 90% agreement between researchers was reached. Only one reviewer conducted the quality appraisal of studies, though scores were discussed with a second reviewer and no study was excluded based on the quality appraisal. The dearth of studies from countries other than the United States limits the generalizability of results. The approach we used to derive monthly costs assumes the total cost reported by studies is equally distributed across the end‐of‐life period considered, which is unlikely to be the case as the cost of care rises toward death.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Published data on costs of dementia care for people approaching the end of life suggest direct costs increase before death, but more information on costs by proximity to death is needed. Informal costs of care represent a substantial component of total costs but have been rarely measured, and there is little information from countries outside the United States. Understanding informal costs and costs from outside the United States must be a priority given the fast‐projected increase in the number of people who will die with dementia over the next 40 years.

FUNDING INFORMATION

J.L is funded by a Royal Marsden Partners Pan London Research Fellowship Award and the Programa Formacion de Capital Humano Avanzado, Doctorado Becas Chile, 2018 (folio 72190265). DY is supported by Cicely Saunders International. K.E.S. is funded by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Clinician Scientist Fellowship (CS‐2015‐15‐005), I.J.H. is an NIHR Senior Investigator Emeritus. I.J.H. is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. I.J.H. leads the Palliative and End of Life Care theme of the NIHR ARC South London, and co‐leads the national theme in this. The funders did not have any involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or the funding charities.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Leniz J, Yi D, Yorganci E, et al. Exploring costs, cost components, and associated factors among people with dementia approaching the end of life: A systematic review. Alzheimer's Dement. 2021;7:e12198. 10.1002/trc2.12198

Registered PROSPERO (CRD42020166337)

REFERENCES

- 1.Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990‐2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:88‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Projections of mortality and causes of death, 2016 to 2060. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry SI, Murphy TE, Gahbauer E, Sussman LS, Allore HG, Gill TM. Restricting symptoms in the last year of life: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1534‐1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leniz J, Higginson IJ, Stewart R, Sleeman KE. Understanding which people with dementia are at risk of inappropriate care and avoidable transitions to hospital near the end‐of‐life: a retrospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2019;48:672‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sleeman KE, Perera G, Stewart R, Higginson IJ. Predictors of emergency department attendance by people with dementia in their last year of life: retrospective cohort study using linked clinical and administrative data. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:20‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarricone R. Cost‐of‐illness analysis. What room in health economics?. Health Policy. 2006;77:51‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quentin W, Riedel‐Heller SG, Luppa M, Rudolph A, König HH. Cost‐of‐illness studies of dementia: a systematic review focusing on stage dependency of costs. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:243‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaller S, Mauskopf J, Kriza C, Wahlster P, Kolominsky‐Rabas PL. The main cost drivers in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:111‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen‐Mansfield J, Skornick‐Bouchbinder M, Brill S. Trajectories of End of Life: a Systematic Review. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73:564‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardiner C, Brereton L, Frey R, Wilkinson‐Meyers L, Gott M. Exploring the financial impact of caring for family members receiving palliative and end‐of‐life care: a systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2014;28:375‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:240‐245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J. In: Cochrane, ed. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. 2019. Updated July 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank Group . World Develpment Indicators database, World Bank. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner C, Ingleton C, Ryan T, Ward S, Gott M. What cost components are relevant for economic evaluations of palliative care, and what approaches are used to measure these costs? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:323‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. 2006.

- 16.Crouch E, Probst JC, Bennett K, Eberth JM. Differences in Medicare utilization and expenditures in the last six months of life among patients with and without Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:126‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daras LC, Feng Z, Wiener JM, Kaganova Y. Medicare expenditures associated with hospital and emergency department use among beneficiaries with dementia. Inquiry. 2017;54:46958017696757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldfeld KS, Stevenson DG, Hamel MB, Mitchell SL. Medicare expenditures among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:824‐830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gozalo P, Plotzke M, Mor V, Miller SC, Teno JM. Changes in Medicare costs with the growth of hospice care in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1823‐1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gozalo PL, Miller SC, Intrator O, Barber JP, Mor V. Hospice effect on government expenditures among nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:134‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Fahle S, Marshall SM, Du Q, Skinner JS. Out‐of‐pocket spending in the last five years of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:304‐309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:729‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb VL, Sloan FA, Nathan AS. Dementia and Medicare at life's end. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:714‐732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormick WC, Hardy J, Kukull WA, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in managed care patients with Alzheimer's disease during the last few years of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1156‐1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller SC, Intrator O, Gozalo P, Roy J, Barber J, Mor V. Government expenditures at the end of life for short‐ and long‐stay nursing home residents: differences by hospice enrollment status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1284‐1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholas LH, Bynum JP, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR, Langa KM. Advance directives and nursing home stays associated with less aggressive end‐of‐life care for patients with severe dementia. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:667‐674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ornstein KA, Zhu CW, Bollens‐Lund E, et al. Medicare expenditures and health care utilization in a multiethnic community‐based population with dementia from incidence to death. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32:320‐325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pyenson B, Connor S, Fitch K, Kinzbrunner B. Medicare cost in matched hospice and non‐hospice cohorts. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:200‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pyenson B, Sawhney TG, Steffens C, et al. The real‐world Medicare costs of Alzheimer disease: considerations for policy and care. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25:800‐809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein KA, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Interactive effects of dementia severity and comorbidities on Medicare expenditures. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:305‐315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckerman RB, Stearns SC, Sheingold SH. Hospice use, hospitalization, and Medicare spending at the end of life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71:569‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sampson E, Mandal U, Holman A, Greenish W, Dening KH, Jones L. Improving end of life care for people with dementia: a rapid participatory appraisal. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2:108‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Plas AG, Oosterveld‐Vlug MG, Pasman HR, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. Relating cause of death with place of care and healthcare costs in the last year of life for patients who died from cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure and dementia: a descriptive study using registry data. Palliat Med. 2017;31:338‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spilsbury K, Rosenwax L. Community‐based specialist palliative care is associated with reduced hospital costs for people with non‐cancer conditions during the last year of life. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann F, Strautmann A, Allers K. Hospitalization at the end of life among nursing home residents with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:470‐477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aaltonen M, Forma L, Pulkki J, Raitanen J, Rissanen P, Jylha M. Changes in older people's care profiles during the last 2 years of life, 1996‐1998 and 2011‐2013: a retrospective nationwide study in Finland. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDaid D. Estimating the costs of informal care for people with Alzheimer's disease: methodological and practical challenges. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:400‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wimo A, Jönsson L, Fratiglioni L, et al. The societal costs of dementia in Sweden 2012 – relevance and methodological challenges in valuing informal care. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2016;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stearns SC, Norton EC. Time to include time to death? The future of health care expenditure predictions. Health Econ. 2004;13:315‐327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mataqi M, Aslanpour Z. Factors influencing palliative care in advanced dementia: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:145‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan T, Gardiner C, Bellamy G, Gott M, Ingleton C. Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: the views of medical and nursing staff. Palliat Med. 2012;26:879‐886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. Timing of GP end‐of‐life recognition in people aged ≥75 years: retrospective cohort study using data from primary healthcare records in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leniz J, Higginson IJ, Yi D, Ul‐Haq Z, Lucas A, Sleeman KE. Identification of palliative care needs among people with dementia and its association with acute hospital care and community service use at the end‐of‐life: A retrospective cohort study using linked primary, community and secondary care data. Palliat Med. 2021;026921632110198. 10.1177/02692163211019897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiers G, Matthews FE, Moffatt S, et al. Impact of social care supply on healthcare utilisation by older adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Age Ageing. 2019;48:57‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gannon B, Davin B. Use of formal and informal care services among older people in Ireland and France. Eur J Health Econ. 2010;11:499‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonsang E. Does informal care from children to their elderly parents substitute for formal care in Europe?. J Health Econ. 2009;28:143‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higginson IJ, Yi D, Johnston BM, et al. Associations between informal care costs, care quality, carer rewards, burden and subsequent grief: the international, access, rights and empowerment mortality follow‐back study of the last 3 months of life (IARE I study). BMC Medicine. 2020;18:344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aworinde J, Werbeloff N, Lewis G, Livingston G, Sommerlad A. Dementia severity at death: a register‐based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.