Abstract

People with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) have difficulty with socio-emotional functioning; however, research on facial emotion recognition (FER) remains inconclusive. Individuals with ASD might be using atypical compensatory mechanisms that are exhausted in more complex tasks. This study compared response accuracy and speed on a forced-choice FER task using neutral, happy, sad, disgust, anger, fear and surprise expressions under both timed and non-timed conditions in children with and without ASD (n = 18). The results showed that emotion recognition accuracy was comparable in the two groups in the non-timed condition. However, in the timed condition, children with ASD were less accurate in identifying anger and surprise compared to children without ASD. This suggests that people with ASD have atypical processing of anger and surprise that might become challenged under time pressure. Understanding these atypical processes, and the environmental factors that challenge them, could be beneficial in supporting socio-emotional functioning in people ASD.

Keywords: disorders, ASD, emotion perception, facial perception

Introduction

Among the core diagnostic criteria comprising autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are difficulties with social communication and interaction, difficulties with socio-emotional reciprocity, non-verbal communication and developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although difficulty with facial emotion recognition (FER) is not a required Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criterion, it is central skill for successful social interaction and is often listed as a diagnostic marker of ASD (Uljarevic & Hamilton, 2013). However, the nature or even the existence of such an ‘impairment’ is debated. Although impaired processing and recognition of facial emotions have often been reported in people with autism (Capps et al., 1992; Griffiths et al., 2019; Hobson et al., 1986; Weeks & Hobson, 1987; Yeung et al., 2014), some studies of ASD have not found difficulties with these skills (Ozonoff et al., 1991; Ponnet et al., 2004; Rump et al., 2009; Tracy et al., 2011) or have reported only partial difficulties with specific negative emotions (Ashwin et al., 2006; Enticott et al., 2014). In a meta-analysis, Uljarevic and Hamilton (Uljarevic & Hamilton, 2013) reviewed 48 studies, reporting that when happiness was used as a baseline, only the recognition of fear was impaired in those with ASD, and even that difference disappeared after Bonferroni correction. In an online study, Ola and Gullon-Scott (Ola & Gullon-Scott, 2020) examined female adults with ASD and found that FER difficulties were related to co-occurring alexithymia rather than ASD itself.

One of the main factors researchers have suggested contributes to the discrepancy in findings about FER impairments in ASD are experimental task differences (Harms et al., 2010). Diverse experimental tasks have been used in the literature – for example a delayed matching task (Celani et al., 1999), labelling faces (Yeung et al., 2020), morphing the six basic emotions (Bal et al., 2010), mental rotation (Nagy et al., 2018; Tantam et al., 1989) or a forced choice between two possibilities (Spezio et al., 2007). Matching tasks may allow people with ASD to use compensatory strategies (Hariri et al., 2000; Teunisse & de Gelder, 2001), forced-choice labelling tasks may allow for guessing (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997) and free labelling tasks have proven to be affected by language difficulties in ASD rather than FER per se (Uljarevic & Hamilton, 2013). Although they have received less research, the length of stimulus exposure and processing times have also revealed diverse findings. Children, adolescents and adults with ASD demonstrated longer reaction times (RTs) in FER tasks (Bal et al., 2010; Dalton et al., 2005; Sucksmith et al., 2013), whereas Tracy et al. (Tracy et al., 2011) found that children with ASD had comparably rapid RTs to children without ASD. When Clark et al. (Clark et al., 2008) used very brief time durations (15 and 30 ms) to prevent participants from using compensatory cognitive mechanisms, at 15 ms, all of the groups performed equally around the chance level across tasks. However, participants with ASD recognised emotional expressions less accurately than the participants without ASD when the stimuli were presented for 30 ms. When Celani et al. (Celani et al., 1999) extended this time to 750 ms, children with ASD were less accurate at recognising facial emotions compared to children without ASD and children with Down’s syndrome. When Rump et al. (Rump et al., 2009) used 500 ms exposure of video recordings of facial expressions, only the youngest children (5–7 years) and the adults with ASD performed poorly compared to those without ASD. In contrast, other studies reported that a decreased presentation length of visual stimuli affected autistic and non-autistic populations in a similar manner. Tracy et al. (Tracy et al., 2011) presented facial expressions of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, pride, sadness and surprise for 1,500 ms and asked participants to respond within this time frame, and found no group differences in emotion recognition accuracy or speed. When only responses within the first 800 ms were considered, the performance of the two groups remained comparable. The diverse findings in FER in ASD may be due to methodological diversity – that is, in certain situations, individuals with ASD are less able to use atypical compensatory mechanisms in more complex experimental tasks (Grossman & Tager-Flusberg, 2008; Grossman et al., 2000) and under time pressure (Celani et al., 1999; Clark et al., 2008; Rump et al., 2009). People with ASD were found to use explicit and more effortful compensatory mechanisms in FER tasks compared to people without ASD who use faster, implicit mechanisms instead (Harms et al., 2010). Such compensatory mechanisms include following explicit rules to associate certain facial features with emotions, such as a frown with anger, when determining a facial expression (Rutherford & McIntosh, 2007; Teunisse & de Gelder, 2001). Combined ERP and eye-tracking revealed an experience-dependent specialisation for face processing that results in an automatic and efficient neural network in children without ASD (Meaux et al., 2014). Due to differences in perceptual processes, it was suggested that children with ASD spend less time attending to socially relevant information, possibly resulting in atypical processing; this deficit becomes further compromised with age (Chawarska & Shic, 2009). Price and Friston (Price & Friston, 2002) suggested that decreased activity in brain regions responsible for socio-emotional functions is compensated by an increase in activity of other regions that could fulfil some of the functions using alternative pathways. In the case of ASD, a decreased connectivity between the posterior cingulate and precuneus areas (Di Martino et al., 2014) was found to be compensated by enhanced activities in the ventromedial prefrontal and anterior temporal areas within the social brain (Subbaraju et al., 2018). Such explicit compensatory mechanisms may be responsible for the mixed results in the above FER tasks with people with ASD when compared to those without ASD. One way to detect possible compensation strategies in experiments is to use a time limit that is sufficient for template-based implicit processing in people without ASD but might be insufficient for alternative compensatory mechanisms in ASD. The present study explored whether longer stimulus presentation times allow autistic individuals to use compensatory mechanisms in emotion recognition tasks and if time pressure resulted in decreased performance.

The study compared performances on a forced-choice FER task using the six basic emotions (Ekman et al., 1983) both under timed and non-timed conditions in children with ASD (ASD) and without ASD (NA). It hypothesised that children with ASD would underperform compared to those without ASD in the timed condition, but that their emotion recognition performance would be less affected in the non-timed condition. Performance was measured by the accuracy of the children’s responses and the speed of these responses (measured by RTs).

Methods

Participants

Eighteen participants took part in the study, aged between 12 and 17 years old. Nine of these participants were in the ASD group, officially diagnosed with Autistic Disorder by the National Health Service. The data were collected in 2012 and 2013 and all the children were diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (4th Edition, revised text version) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). All the children with autism attended special autism units in mainstream schools and were verbal. Nine children were in the control or non-ASD group (NA). The mean age of ASD group was 179 months, SD = 21.83 (age range: 155–209 months), eight males, one female and the mean age of NA groups was 188 months SD = 20.66 (age range: 151–212 months) four males and five females. Participants were all pupils at Monifieth High School, a mainstream school. They were recruited through distribution of consent forms to parents via the Headteacher. Approval for this study was applied for and approved by the University of Dundee’s, University Research Ethics Committee (UREC) and the Education Department of Angus Council. Monifieth High School also consented to the study. Signed informed consent was required from parents and children before participation in the study.

Materials

The Autism Screener Questionnaire (ASQ) (Berument et al., 1999) was used in order to confirm the diagnosis of autism in the two groups.

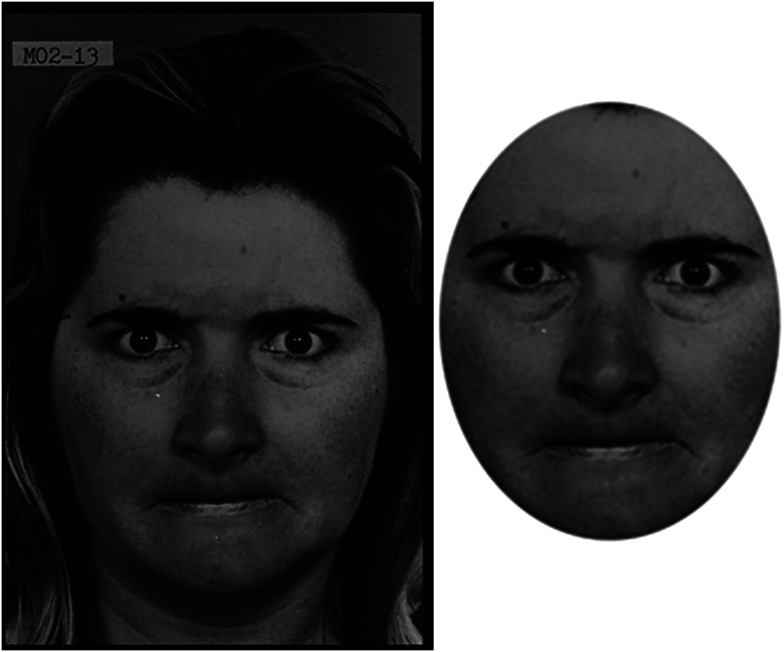

The FER task used photos taken from the Pictures of Facial Affect set (Ekman & Friesen, 1975). The current study used 66 photos from this set of 10 actors (five males and five females) each displaying a neutral expression as well as the six basic emotions of happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise and disgust (see the ID numbers of each picture in Table A1 of the Appendix). In order to prevent participants recognising the picture from other non-facial features, each picture was edited using ADOBE Photoshop 7.0 software. This removed hair, jewellery and background, leaving only the face visible (see Figure 1 for an example of the stimuli before and after editing). The FER experiment was conducted using SuperLab Pro (version 2.0) software run on a 15-inch Toshiba laptop. Verbal and Visuo-spatial ability was measure using the Vocabulary and the Block Design subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Wechsler, 1991).

Figure 1.

Example of stimuli before and after editing. Unedited angry woman (left) and edited angry woman (right).

Procedure

Before testing could commence, the parents of the children returned the ASQ and a signed consent form in a sealed envelope. After parental consent, children were also required to sign the consent form before beginning the task. The order of the study was: the FER task, the Block Design subtest and then the Vocabulary subtest.

The Facial Emotion Recognition Task

The FER task had two parts, a timed and non-timed experiment. In the timed experiment participants had 1,200 ms to respond whereas in the non-timed experiment participants had no time limit to respond within. The same procedure was applied in both the timed and the non-timed experiments.

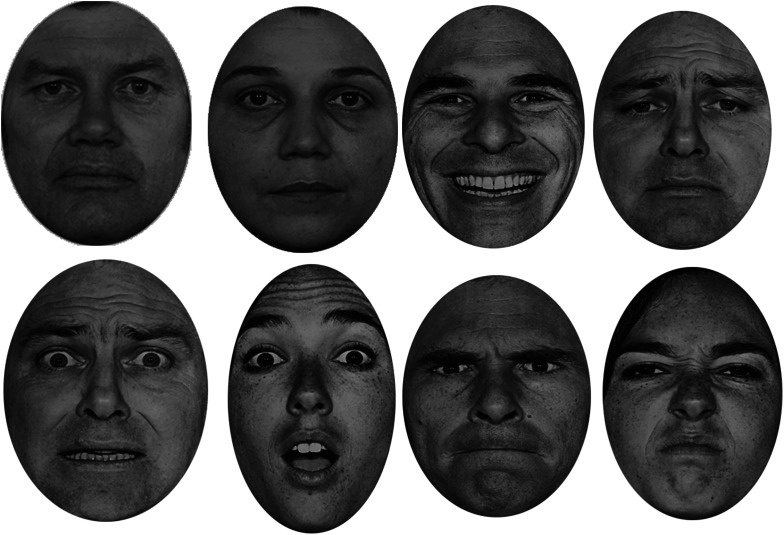

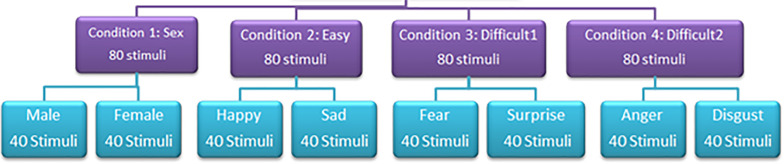

The experiment was broken down into four conditions; sex (male and female), ‘easy’ (happy and sad), ‘difficult 1’ (fear and surprise) and ‘difficult 2’ (anger and disgust) (see Figure 2 for illustration of the faces). In each condition, one stimulus was presented at a time in a forced-choice task. Participants were asked to decide which type of stimulus was displayed out of two possible options. Each condition was administered in four blocks and the key responses were randomised and counterbalanced for each emotion. There were 80 stimuli in each condition and 20 stimuli in each block. Over the two experiments (timed/non-timed) there were 640 stimuli. This is illustrated in Figure 3 (see Figure 3). The order of the conditions was randomised across participants. The order in which pictures appeared in each block was randomised by the Superlab Pro software.

Figure 2.

Examples of the eight different stimuli used in their pairings. From top left to bottom right: male; female; happy; sad; fear; surprise; anger; disgust.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing structure of experiments, conditions and stimuli used in both the timed and non-timed experiments.

Before each block of trials, instructions appeared on the screen to inform the participant of which key (‘l’ covered with blue sticker; ‘s’ covered with red sticker) corresponded to which emotion.

For the timed experiment, stimuli were presented on screen only for 1,200 ms, or if shorter, until the participant responded. For the non-timed experiment stimuli remained on the screen until the participant responded.

The responses and time taken (milliseconds) to respond were recorded for each condition. The FER task began with a short practice test encompassing examples from all conditions so that children familiarised themselves with the task. The practice session contained four example pictures from each block, resulting in 16 practice pictures in total.

The order of experiments – timed/non-timed – was randomised across participants.

In total, the two experiments and the block design and vocabulary subtests lasted for approximately 35 minutes. During this time, children were able to take short breaks in between the blocks and tasks if they wished.

Results

The two groups were comparable in terms of age, Vocabulary and Block Design performances (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Means and (standard deviations) for age, block design and vocabulary subtest scaled scores for the ASD and NA groups.

| ASD | NA | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 178.89 (21.83) | 187.67 (20.66) | 0.88 | .61 |

| Range | 151–212 | |||

| Block design (scaled scores) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.22 (3.93) | 11.44 (3.78) | 0.8 | .69 |

| Range | 4–16 | |||

| Vocabulary (scaled scores) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.33 (2.65) | 9.33 (2.69) | 0.67 | .71 |

| Range | 4–13 | |||

| ASQ (scores) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.44 (8.47) | 4.56 (3.17) | 4.61 | <.001 |

| Range | 1–33 | |||

Abbreviations: ASD = autism spectrum disorders; ASQ = Autism Screener Questionnaire; NA = non-ASD.

An 8 × 2 mixed design analysis of variance was conducted on the effect of the nature of the stimuli (emotions: man, woman, happy, sad, fear, surprise, anger, disgust) and the groups ‘Group’ (children with autism spectrum disorders: ASD, and children without: NA) on the number of the correct responses. When the Mauchly’s test of sphericity was significant, the Greenhouser-Geisser correction was used to interpret the results. When significant emotion*group interaction was found, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were used with Bonferroni corrections. p < .05 was accepted as significant throughout.

Timed Condition

Correct Responses

There was a significant main effect of emotions, F (3.77, 60.5) = 37.8, p < .01, and the Emotion*Group interaction was significant F (3.77, 60.5) = 3.4, p = .016, . The main effect of Group was not significant F (1, 16) = 2.15, p = .16.

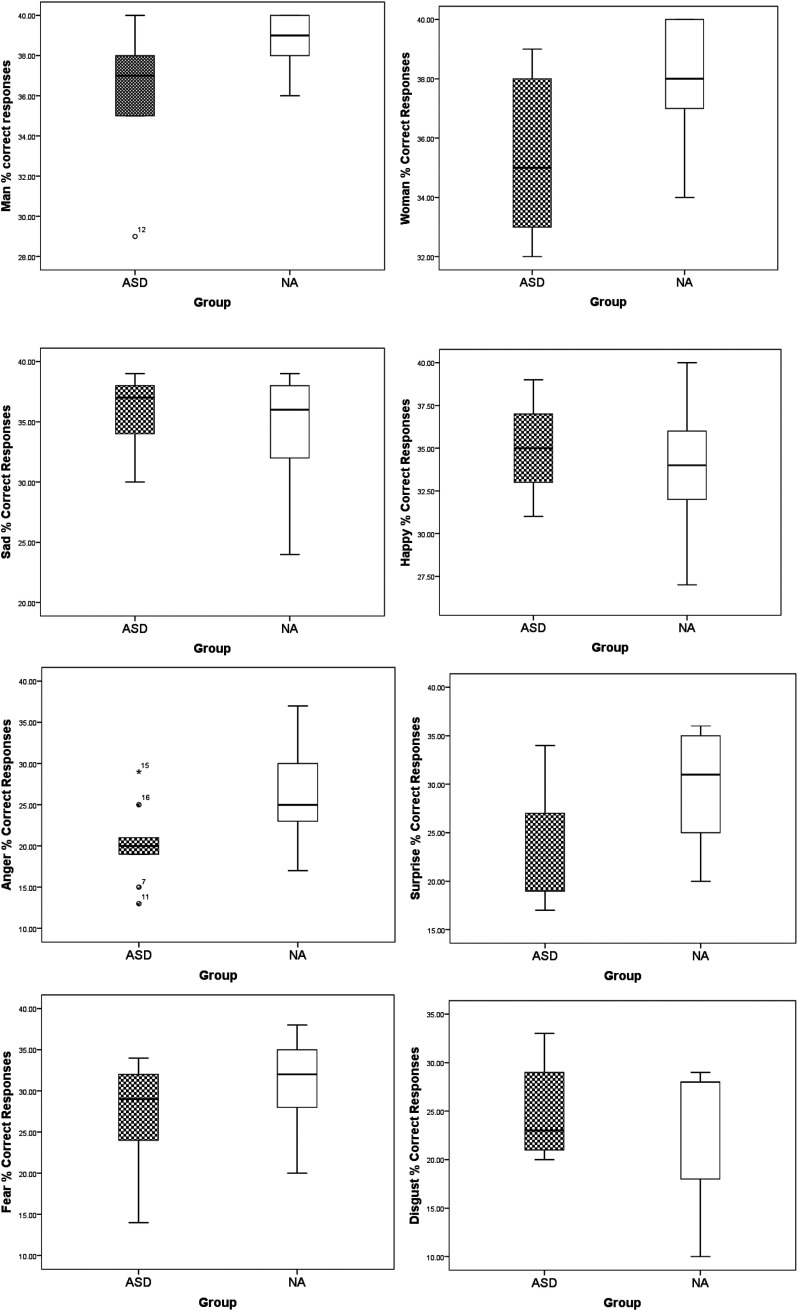

Post-hoc pairwise comparison using Bonferroni correction showed that children with ASD had a significantly lower number of correct responses for anger and surprise compared to children without ASD. The other comparisons were non-significant, although, on a tendency level (p < .06), children with ASD also had a lower mean of correct recognition of the ‘Woman’ faces compared to children without ASD (see Table 2). Given the small sample sizes, boxplots 1–8 (see Figure 4) show the possible outliers for each emotion in the two groups. Inspection of the boxplots indicates potential outliers in the ASD group in the man and the anger emotions. Given the expected variability in the ASD group, these data have been kept in the analysis.

Table 2.

Mean percentages of correct responses (mean) and standard deviations (SD) based on type of emotion and group in the timed condition.

| Man | Woman | Sad | Happy | Surprise | Fear | Disgust | Anger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD mean (SD) | 36.56 (3.36) | 35.44 (2.70) | 35.78 (3.07) | 35.11 (2.57) | 22.78 (6.18) | 27.00 (6.42) | 24.78 (4.55) | 20.33 (4.77) |

| NA mean (SD) | 38.67 (1.50) | 37.78 (2.17) | 34.22 (4.99) | 33.89 (4.46) | 29.67 (6.08) | 30.67 (6.00) | 23.22 (7.29) | 27.00 (6.65) |

| p | .10 | .06 | .44 | .49 | .03 | .23 | .60 | .03 |

Abbreviations: ASD = autism spectrum disorders; NA = non-ASD.

Figure 4.

Boxplot diagrams of the data in the eight conditions in the two groups in the timed experiment, percentage of correct responses.

Response Times

There was a significant main effect of emotion, F (2.56, 41.01) = 17.138, p < .001, . There was no significant main effect of Group F (1, 16) = 0.46, p = .51, or interaction between Emotion*Group, F (2.56, 41.01) = 1.01, p = .38. Although there was no significant Emotion*Group interaction, the mean response times in each group are shown in Table 3 for information (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean reaction times (mean) and standard deviations (SD) based on type of emotion and group in the timed experiment.

| Man | Woman | Sad | Happy | Surprise | Fear | Disgust | Anger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD mean (SD) | 685.0 (51.60) |

682.07 (62.09) |

660.86 (54.75) |

618.92 (60.99) |

766.33 (46.02) |

758.80 (45.77) |

735.97 (72.70) |

735.16 (54.22) |

| NA mean (SD) | 666.15 (74.73) |

669.58 (84.97) |

691.40 (62.30) |

660.12 (73.55) |

771.50 (100.48) |

769.48 (100.32) |

760.19 (88.31) |

787.96 (87.75) |

Abbreviations: ASD = autism spectrum disorders; NA = non-ASD.

Non-Timed Condition

Correct Responses

There was a significant main effect of emotion, F (3.89, 62.16) = 11.17, p < .001, . The main effect of Group F (1, 16) = 1.19, p = .29, and the interaction between Emotion*Group have not been significant, F (3.89, 62.16) = 0.99, p = .42. Although there was no significant Emotion*Group interaction, the mean percentages of the correct responses in each group are shown in Table 4 for information (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean percentage of correct responses (mean) and standard deviations (SD) based on type of emotion and group in the non-timed experiment.

| Man | Woman | Sad | Happy | Surprise | Fear | Disgust | Anger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD mean (SD) | 36.00 (6.61) |

35.56 (5.10) |

34.44 (4.67) |

34.33 (3.43) |

31.78 (7.03) |

33.00 (6.63) |

23.78 (8.56) |

21.89 (10.19) |

| NA mean (SD) | 38.33 (3.57) |

38.67 (2.24) |

35.11 (9.89) |

35.00 (7.73) |

32.44 (8.89) |

33.22 (7.60) |

27.67 (9.25) |

30.11 (7.32) |

Abbreviations: ASD = autism spectrum disorders; NA = non-ASD.

Response Times

There was a significant main effect of emotion, F (1.66, 26.48) = 14.16, p < .001, . However, there was no main effect of Group F (1, 16) = 0.76, p = .40 or significant interaction between Emotion*Group, F (1.66, 26.48) = 0.97, p = .38. Although there was no significant Emotion*Group interaction, the mean response times in each group are shown in Table 5 for information (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean reaction times (mean) and standard deviations (SD) based on type of emotion and group in the non-timed experiment.

| Man | Woman | Sad | Happy | Surprise | Fear | Disgust | Anger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD mean (SD) | 840.52 (205.98) |

861.09 (201.23) |

869.68 (201.74) |

869.68 (115.46) |

1272.06 (551.71) |

1347.27 (606.53) |

1245.74 (711.83) |

1224.98 (591.74) |

| NA mean (SD) | 765.71 (146.55) |

767.15 (112.98) |

838.30 (141.04) |

766.31 (92.99) |

1036.55 (191.44) |

1047.61 (198.23) |

1116.11 (264.64) |

1179.56 (227.47) |

Abbreviations: ASD = autism spectrum disorders; NA = non-ASD.

Discussion

This study investigated whether recognition of six basic emotions was affected by task difficulty – namely, time pressure. It hypothesised that children with and without ASD would perform comparably when there was no time pressure for their responses. As predicted, the accuracy of emotion recognition was comparable in the two groups in the non-timed condition. In the timed condition, however, children with ASD were less accurate in identifying anger and surprise compared to children without ASD. These results could partially reconcile studies with contradictory outcomes regarding emotion recognition in children with ASD. Further, when the groups were matched in terms of age and IQ, differences in emotion recognition were undetectable. Finally, difficulties in the accuracy of emotion recognition only appeared when children with ASD were under time pressure. It was suggested that instead of the theory that those with ASD cannot recognise facial emotions, it might be that they use ‘atypical’ mechanisms to achieve FER (Hobson, 1986; Homer & Rutherford, 2008). While performance on FER tasks might be comparable, people with ASD displayed increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and precuneus and decreased activity in the amygdala and fusiform gyrus when performing emotion recognition tasks compared to non-autistic controls (Ashwin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004). The ACC and precuneus are related to self-monitoring and attentional load, indicating that emotion recognition tasks might be more cognitively effortful for people with ASD compared to people without ASD (Harms et al., 2010) – when task demands increase, performance diminishes. When Clark et al. (Clark et al., 2008) restricted stimulus presentation to 30 ms, they observed a marked emotion recognition deficit in adults with ASD. However, when Tracy et al. (Tracy et al., 2011) used a 1,500 ms time limit for stimulus presentation, there were no group differences. The current study used a 1,200 ms limit for stimulus presentation and response; it found that children with ASD only decreased accuracy for anger and surprise reactions compared to children without ASD.

Several studies have reported an overall decreased performance in recognition of negative emotions such as anger, fear and other ‘cognitive’ emotions in children with ASD (Ashwin et al., 2006; Baron-Cohen et al., 1993; Humphreys et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2015). The present study’s lack of differences in accuracy under no time pressure supports those studies in which children with and without ASD recognised emotions equally well (Jones et al., 2011; Loveland et al., 2008). This study refines this previous work, reconciling those that found (vs. those that did not find) differences in FER.

Atypical processing of anger was reported by several studies (Ashwin et al., 2007; Lindner & Rosén, 2006). A recent study by Leung et al. (Leung et al., 2019) found no group differences with RTs in recognising angry and happy faces, but the neural responses using magnetoencephalography (MEG) showed otherwise. Children without ASD showed greater right middle temporal and superior temporal activation in response to angry faces than to happy faces, but children with ASD showed greater fronto-temporal activation in response to happy faces than to angry faces. Additionally, the posterior cingulate and thalamus were less active in response to both angry and happy faces in children with ASD compared to children without ASD. Leung et al. (Leung et al., 2019), who studied children 7–10 years old, speculated that the results might reflect a maturational delay (Lindner & Rosén, 2006) in children with ASD and that the recognition of anger improves later in adolescence. Although our sample size is very small, the children were 12–17 years of age and the recognition of anger in the ASD group was still lagging behind the performance of children without ASD, making the above maturational theory less plausible. In a study by Malaia et al. (Malaia et al., 2019), children and adolescents with ASD failed to show the early distinctive neural responses to anger and fear that are typical to those without ASD, and Wright et al. (Wright et al., 2012) found a decrease of gamma power for anger, disgust and sadness in the left supramarginal and left precentral gyrus in ASD, while people without ASD showed increases of gamma power. Such results support an atypical neural processing hypothesis in emotion processing in ASD. In our study, employing time pressure might have challenged the atypical, less efficient neural processes in ASD, resulting in less accuracy in responses to angry faces in the timed experiment, but no difference in the recognition in the non-timed experiment.

It has been suggested that the recognition of surprise, a cognitive emotion that is related to understanding other people’s beliefs and intentions, is more difficult for people with ASD (Baron-Cohen et al., 1993; Gross, 2004; Smith et al., 2010), although many studies have found no evidence for such impairment (Humphreys et al., 2007; Uljarevic & Hamilton, 2013). Nagy et al. (Nagy et al., 2018) even found a faster recognition of surprise in ASD. The study, however, used rotated images, thus the advantage in the recognition was likely related to a faster mental rotation of surprised faces in ASD (Nagy et al., 2018).

Jones et al. (Jones et al., 2011), using facial and vocal stimuli, found evidence for an impaired recognition of surprise and suggested that as children with ASD typically respond to surprising events with anxiety, parents and caretakers might avoid exposing them to surprise (Jones et al., 2011). Whether children with autism use atypical ways (Hernandez et al., 2009; Pelphrey et al., 2002) or just reduced time to explore socially relevant stimuli and the decreased recognition of surprise is a result of the lack of experience with that emotion is still not known. It is possible that atypical mechanisms in the looking patterns of people with ASD are related to the fact that they spend less time exploring the relevant stimuli, but the way they are processing them is comparable to people without ASD (Pelphrey et al., 2002; Van Der Geest et al., 2002). Neuroimaging studies, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), however, have shown atypical activation in the amygdala and fusiform gyrus in ASD during FER (Ashwin et al., 2007; Critchley et al., 2000). There is growing evidence for an atypical functionality in the posterior cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in ASD (Lau et al., 2020), and the disruption of their connectivity is related to a cognitive inflexibility, a central feature of ASD (Watanabe et al., 2019). The posterior cingulate cortex also mediates between visual and emotional processing (Vogt et al., 2006) and its disruption results in difficulties in children with ASD in socio-emotional processes.

A major limitation is the very small sample in the study; recruitment sources to reach children with ASD in Angus, Scotland were limited. Even with the small sample, the effect sizes for the main effects and the interactions were moderate to large; according to Cohen (1988), however, the tendency results (p < .10) could indicate that some of the effects might have been missed. It is also important to note that only the ASQ (Berument et al., 1999) was used to confirm group membership. While all children with ASD had confirmed diagnoses as a basis of their admission to the special autism unit from which they were recruited and their teachers confirmed the diagnoses prior to the testing, the experimenters had no direct access to the clinical notes on the diagnoses. Future studies could utilise diagnostic tools, including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G); (Lord et al., 2000) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (Lord et al., 1994). Future studies could include full IQ testing to ensure that no IQ-related differences contribute to outcome measures. The use of still pictures in a forced-choice computerised task in a laboratory environment may pose limitations. Loveland (Loveland, 1991) suggested that people with ASD may have difficulties not with emotion recognition (Loveland et al., 1997) but with perceiving and understanding the significance or ‘affordances’ of their social environment (Gibson, 1979), thus the use of ecologically valid facial-emotional stimuli would lead to more robust results according to the impaired social affordances hypothesis. Further studies using neuroimaging methods and using both time pressure and non-timed conditions could provide a more direct link between atypical processing and socio-emotional behavioural difficulties in children with ASD. Moreover, it is important to note that people with ASD are a heterogeneous population, with no unifying theory to account for the symptoms in the symptom groups as outlined by the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hassan & Mokhtar, 2019). It means that the underlying mechanisms of any social difficulties might be variable, and the conclusions drawn from a small sample study should be regarded as exploratory.

In summary, the results of the study suggest that people with ASD may have atypical processing of facial emotions of anger and surprise and these processes might become challenged under time pressure. Understanding these atypical processes and the environmental factors that challenge them could be beneficial in supporting socio-emotional functioning in people ASD.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the pupils, parents and the staff at Monifieth High, in particular Bev Dobson, for the help in years 2012–2013.

Appendix

See Table A1.

Table A1.

I.D. numbers of pictures used for the facial emotion recognition (FER) task from the pictures of facial affect.

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral | EM2-4, GS1-4, JJ3-4, PE2-4 | C2-3, MF1-2, MO1-5, PF1-2 |

| Happy | EM4-7, GS1-8, JJ4-7, PE2-12 | C2-18, MF1-6, MO1-4, PF1-5 |

| Sad | EM4-24, GS2-1, JJ5-5, PE5-7 | C1-18, MF1-30, MO1-30, PF2-16 |

| Fear | EM5-24, GS1-25, JJ5-13, PE3-21 | C1-23, MF1-26, MO1-23, PF2-30 |

| Surprise | EM2-11, GS1-16, JJ4-13, PE6-2 | C1-10, MF1-9, MO1-14, PF1-16 |

| Anger | EM5-14, GS2-8, JJ3-12, PE2-21 | C2-12, MF2-7, MO2-13, PF2-4 |

| Disgust | EM4-17, GS2-25, JJ3-20, PE4-5 | C1-4, MF2-13, MO2-18, PF1-24 |

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Emese Nagy https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2170-5101

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR fourth edition (text revision). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwin C., Baron-Cohen S., Wheelwright S., O’Riordan M., Bullmore E. T. (2007). Differential activation of the amygdala and the ‘social brain’ during fearful face-processing in Asperger syndrome. Neuropsychologia, 45, 2–14. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwin C., Chapman E., Colle L., Baron-Cohen S. (2006). Impaired recognition of negative basic emotions in autism: A test of the amygdala theory. Social Neuroscience, 1, 349–363. 10.1080/17470910601040772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal E., Harden E., Lamb D., Van Hecke A. V., Denver J. W., Porges S. W. (2010). Emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorders: Relations to eye gaze and autonomic state. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 358–370. 10.1007/s10803-009-0884-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Jolliffe T., Mortimore C., Robertson M. (1997). Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 813–822. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Spitz A., Cross P. (1993). Do children with autism recognise surprise? A research note. Cognition & Emotion, 7, 507–516. 10.1080/02699939308409202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berument S. K., Rutter M., Lord C., Pickles A., Bailey A. (1999). Autism screening questionnaire: Diagnostic validity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 444–451. 10.1192/bjp.175.5.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps L., Yirmiya N., Sigman M. (1992). Understanding of simple and complex emotions in non-retarded children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 33, 1169–1182. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celani G., Battacchi M. W., Arcidiacono L. (1999). The understanding of the emotional meaning of facial expressions in people with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29, 57–66. 10.1023/A:1025970600181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarska K., Shic F. (2009). Looking but not seeing: Atypical visual scanning and recognition of faces in 2 and 4-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1663. 10.1007/s10803-009-0803-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T. F., Winkielman P., McIntosh D. N. (2008). Autism and the extraction of emotion from briefly presented facial expressions: Stumbling at the first step of empathy. Emotion (Washington, DC), 8, 803. 10.1037/a0014124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Critchley H. D., Daly E. M., Bullmore E. T., Williams S. C., Van Amelsvoort T., Robertson D. M., Rowe A., Phillips M., McAlonan G., Howlin P. (2000). The functional neuroanatomy of social behaviour: Changes in cerebral blood flow when people with autistic disorder process facial expressions. Brain, 123, 2203–2212. 10.1093/brain/123.11.2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton K. M., Nacewicz B. M., Johnstone T., Schaefer H. S., Gernsbacher M. A., Goldsmith H. H., Alexander A. L., Davidson R. J. (2005). Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 519–526. 10.1038/nn1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino A., Yan C.-G., Li Q., Denio E., Castellanos F. X., Alaerts K., Anderson J. S., Assaf M., Bookheimer S. Y., Dapretto M. (2014). The autism brain imaging data exchange: Towards a large-scale evaluation of the intrinsic brain architecture in autism. Molecular Psychiatry, 19, 659–667. 10.1038/mp.2013.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P., Friesen W. V. (1975). Pictures of facial affect. Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P., Levenson R. W., Friesen W. V. (1983). Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science (New York, NY), 221, 1208–1210. 10.1126/science.6612338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticott P. G., Kennedy H. A., Johnston P. J., Rinehart N. J., Tonge B. J., Taffe J. R., Fitzgerald P. B. (2014). Emotion recognition of static and dynamic faces in autism spectrum disorder. Cognition and Emotion, 28, 1110–1118. 10.1080/02699931.2013.867832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J. (1979). The theory of affordances. In The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (pp. 127–143). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S., Jarrold C., Penton-Voak I. S., Woods A. T., Skinner A. L., Munafò M. R. (2019). Impaired recognition of basic emotions from facial expressions in young people with autism spectrum disorder: Assessing the importance of expression intensity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 2768–2778. 10.1007/s10803-017-3091-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T. F. (2004). The perception of four basic emotions in human and nonhuman faces by children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 469–480. 10.1023/B:JACP.0000037777.17698.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman J. B., Klin A., Carter A. S., Volkmar F. R. (2000). Verbal bias in recognition of facial emotions in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 369–379. 10.1111/1469-7610.00621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman R. B., Tager-Flusberg H. (2008). Reading faces for information about words and emotions in adolescents with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 681–695. 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A. R., Bookheimer S. Y., Mazziotta J. C. (2000). Modulating emotional responses: Effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. Neuroreport, 11, 43–48. 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms M. B., Martin A., Wallace G. L. (2010). Facial emotion recognition in autism spectrum disorders: A review of behavioral and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychology Review, 20, 290–322. 10.1007/s11065-010-9138-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M. M., Mokhtar H. M. O. (2019). Investigating autism etiology and heterogeneity by decision tree algorithm. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 16, 100215. 10.1016/j.imu.2019.100215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez N., Metzger A., Magné R., Bonnet-Brilhault F., Roux S., Barthelemy C., Martineau J. (2009). Exploration of core features of a human face by healthy and autistic adults analyzed by visual scanning. Neuropsychologia, 47, 1004–1012. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson R. P. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 27, 321–342. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb01836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson R. P., Ouston J., Lee A. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27, 321–342. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb01836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer M., Rutherford M. D. (2008). Individuals with autism can categorise facial expression. Child Neuropsychology, 14, 419–437. 10.1080/09297040802291715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K., Minshew N., Leonard G. L., Behrmann M. (2007). A fine-grained analysis of facial expression processing in high-functioning adults with autism. Neuropsychologia, 45, 685–695. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. R. G., Pickles A., Falcaro M., Marsden A. J. S., Happé F., Scott S. K., Sauter D., Tregay J., Phillips R. J., Baird G., Simonoff E., Charman T. (2011). A multimodal approach to emotion recognition ability in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 275–285. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau W. K. W., Leung M.-K., Zhang R. (2020). Hypofunctional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in autism: Evidence from coordinate-based imaging meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 103, 109986. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung R. C., Pang E. W., Brian J. A., Taylor M. J. (2019). Happy and angry faces elicit atypical neural activation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 4, 1021–1030. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner J. L., Rosén L. A. (2006). Decoding of emotion through facial expression, prosody and verbal content in children and adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 769–777. 10.1007/s10803-006-0105-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C., Risi S., Lambrecht L., Cook E. H., Jr., Leventhal B. L., DiLavore P. C., Pickles A., Rutter M. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223. 10.1023/A:1005592401947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C., Rutter M., Le Couteur A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659–685. 10.1007/BF02172145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland K. A. (1991). Social affordances and interaction II: Autism and the affordances of the human environment. Ecological Psychology, 3, 99–119. 10.1207/s15326969eco0302_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland K. A., Bachevalier J., Pearson D. A., Lane D. M. (2008). Fronto-limbic functioning in children and adolescents with and without autism. Neuropsychologia, 46, 49–62. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland K. A., Tunali–Kotoski B., Chen Y. R., Ortegon J., Pearson D. A., Brelsford K. A., Gibbs M. C. (1997). Emotion recognition in autism: Verbal and nonverbal information. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 579–593. 10.1017/S0954579497001351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaia E., Cockerham D., Rublein K. (2019). Visual integration of fear and anger emotional cues by children on the autism spectrum and neurotypical peers: An EEG study. Neuropsychologia, 126, 138–146. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaux E., Hernandez N., Carteau-Martin I., Martineau J., Barthélémy C., Bonnet-Brilhault F., Batty M. (2014). Event-related potential and eye tracking evidence of the developmental dynamics of face processing. European Journal of Neuroscience, 39, 1349–1362. 10.1111/ejn.12496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E., Paton S. C., Primrose F. E. A., Farkas T. N., Pow C. F. (2018). Speeded recognition of fear and surprise in autism. Perception, 47, 1117–1138. 10.1177/0301006618811768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ola L., Gullon-Scott F. (2020). Facial emotion recognition in autistic adult females correlates with alexithymia, not autism. Autism, 24, 2021–2034. 10.1177/1362361320932727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S., Pennington B. F., Rogers S. J. (1991). Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic individuals: Relationship to theory of mind. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32, 1081–1105. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelphrey K. A., Sasson N. J., Reznick J. S., Paul G., Goldman B. D., Piven J. (2002). Visual scanning of faces in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 249–261. 10.1023/A:1016374617369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K. S., Roeyers H., Buysse A., De Clercq A., Van Der Heyden E. (2004). Advanced mind-reading in adults with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 8, 249–266. 10.1177/1362361304045214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C. J., Friston K. J. (2002). Degeneracy and cognitive anatomy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 416–421. 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01976-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rump K. M., Giovannelli J. L., Minshew N. J., Strauss M. S. (2009). The development of emotion recognition in individuals with autism. Child Development, 80, 1434–1447. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01343.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford M., McIntosh D. N. (2007). Rules versus prototype matching: Strategies of perception of emotional facial expressions in the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 187–196. 10.1007/s10803-006-0151-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J. L., Montagne B., Perrett D. I., Gill M., Gallagher L. (2010). Detecting subtle facial emotion recognition deficits in high-functioning autism using dynamic stimuli of varying intensities. Neuropsychologia, 48, 2777–2781. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spezio M. L., Adolphs R., Hurley R. S. E., Piven J. (2007). Abnormal use of facial information in high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 929–939. 10.1007/s10803-006-0232-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraju V., Sundaram S., Narasimhan S. (2018). Identification of lateralized compensatory neural activities within the social brain due to autism spectrum disorder in adolescent males. European Journal of Neuroscience, 47, 631–642. 10.1111/ejn.13634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucksmith E., Allison C., Baron-Cohen S., Chakrabarti B., Hoekstra R. A. (2013). Empathy and emotion recognition in people with autism, first-degree relatives, and controls. Neuropsychologia, 51, 98–105. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantam D., Monaghan L., Nicholson H., Stirling J. (1989). Autistic children's ability to interpret faces: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 623–630. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. J., Maybery M. T., Grayndler L., Whitehouse A. J. (2015). Evidence for shared deficits in identifying emotions from faces and from voices in autism spectrum disorders and specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 50, 452–466. 10.1111/1460-6984.12146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunisse J.-P., de Gelder B. (2001). Impaired categorical perception of facial expressions in high-functioning adolescents with autism. Child Neuropsychology, 7, 1–14. 10.1076/chin.7.1.1.3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy J. L., Robins R. W., Schriber R. A., Solomon M. (2011). Is emotion recognition impaired in individuals with autism spectrum disorders? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 102–109. 10.1007/s10803-010-1030-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uljarevic M., Hamilton A. (2013). Recognition of emotions in autism: A formal meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1517–1526. 10.1007/s10803-012-1695-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Geest J. N., Kemner C., Verbaten M. N., Van Engeland H. (2002). Gaze behavior of children with pervasive developmental disorder toward human faces: A fixation time study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 669–678. 10.1111/1469-7610.00055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt B. A., Vogt L., Laureys S. (2006). Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. Neuroimage, 29, 452–466. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. T., Dapretto M., Hariri A. R., Sigman M., Bookheimer S. Y. (2004). Neural correlates of facial affect processing in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 481–490. 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Lawson R. P., Walldén Y. S., Rees G. (2019). A neuroanatomical substrate linking perceptual stability to cognitive rigidity in autism. Journal of Neuroscience, 39, 6540–6554. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2831-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1991). The Wechsler intelligence scale for children – third edition. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks S. J., Hobson R. P. (1987). The salience of facial expression for autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 28, 137–151. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright B., Alderson-Day B., Prendergast G., Bennett S., Jordan J., Whitton C., Gouws A., Jones N., Attur R., Tomlinson H. (2012). Gamma activation in young people with autism spectrum disorders and typically-developing controls when viewing emotions on faces. PLoS One, 7(7): e41326. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung M. K., Han Y. M., Sze S. L., Chan A. S. (2014). Altered right frontal cortical connectivity during facial emotion recognition in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 1567–1577. 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.08.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung M. K., Lee T. L., Chan A. S. (2020). Impaired recognition of negative facial expressions is partly related to facial perception deficits in adolescents with high-functioning autism Spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 1596–1606. 10.1007/s10803-019-03915-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]