There are unique potential stressors faced by the gastroenterologist at each career stage, some more preeminent early on. One such stressor, particularly in a procedure-intensive specialty like gastroenterology (GI), is medical professional liability (MPL), historically termed “medical malpractice.” GI is the 2nd-highest internal medicine subspecialty in both MPL claims made and paid (1), yet instruction on MPL risk and mitigation is scarce in fellowship, as is the available GI-related literature on the topic. This scarcity may generate untoward stress and unnecessarily expose gastroenterologists to avoidable MPL pitfalls. Thus, it is vital for GI trainees, early-career gastroenterologists, and indeed even seasoned gastroenterologists to have a working and updated knowledge of the general principles of MPL and GI-specific considerations. Such understanding can help preserve physician well-being, increase professional satisfaction, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve healthcare outcomes (2).

To this end, we herein provide a focused review of: i) key MPL concepts, ii) trends in MPL claims, iii) GI-related MPL risk scenarios and considerations, iv) adverse provider defensive mechanisms in response to MPL risk, v) key documentation tenets, vi) challenges posed by increased reliance on telemedicine, and vii) the concept of “vicarious liability.”

PRINCIPLES OF MPL

MPL falls under the umbrella of tort law, which itself falls under the umbrella of civil law; that is, civil (as opposed to criminal) justice governs torts—including but not limited to MPL claims—as well as other areas of law concerning non-criminal injury (3). A tort is a “civil wrong that unfairly causes another to experience loss or harm resulting in legal liability” (3). MPL claims assert the tort of negligence (similar to the concept of “incompetence”) and endeavor to compensate the harmed patient/individual while simultaneously dissuading sub-optimal medical care by the provider in the future (4,5). A successful MPL claim must prove four elements: i) that the tortfeasor (e.g., the gastroenterologist) owed a duty of care to the injured party and ii) breached that duty, iii) causing iv) damages (6). The burden of proof in tort law, and specifically the context of MPL, is not “beyond a reasonable doubt” (criminal law) but rather “to a reasonable medical probability” (7).

TRENDS IN MPL CLAIM PREVALENCE AND COMPENSATION

Based on data compiled by the MPL Association, 278,220 MPL claims were made in the United States from 1985–2012 (3,8–10). Among these, 1.8% involved GI, which ranked 17th out of 20 specialties surveyed (9). While the number of paid claims over this timeframe decreased in GI by 34.6% (from 18.5 to 12.1 cases per 1,000 physician-years), there was a concurrent 23.3% increase in average claim compensation (11,12); essentially, there were fewer paid GI-related claims but higher payouts per paid claim. From 2009–2018, average legal defense costs for paid GI-related claims were $97,392, and average paid amount was $330,876 (1).

MPL RISK SCENARIOS

Many MPL claims relate to situations involving medical errors or adverse events (AEs), be they procedural or non-procedural. However other aspects of GI also carry MPL risk, as discussed below.

Informed consent

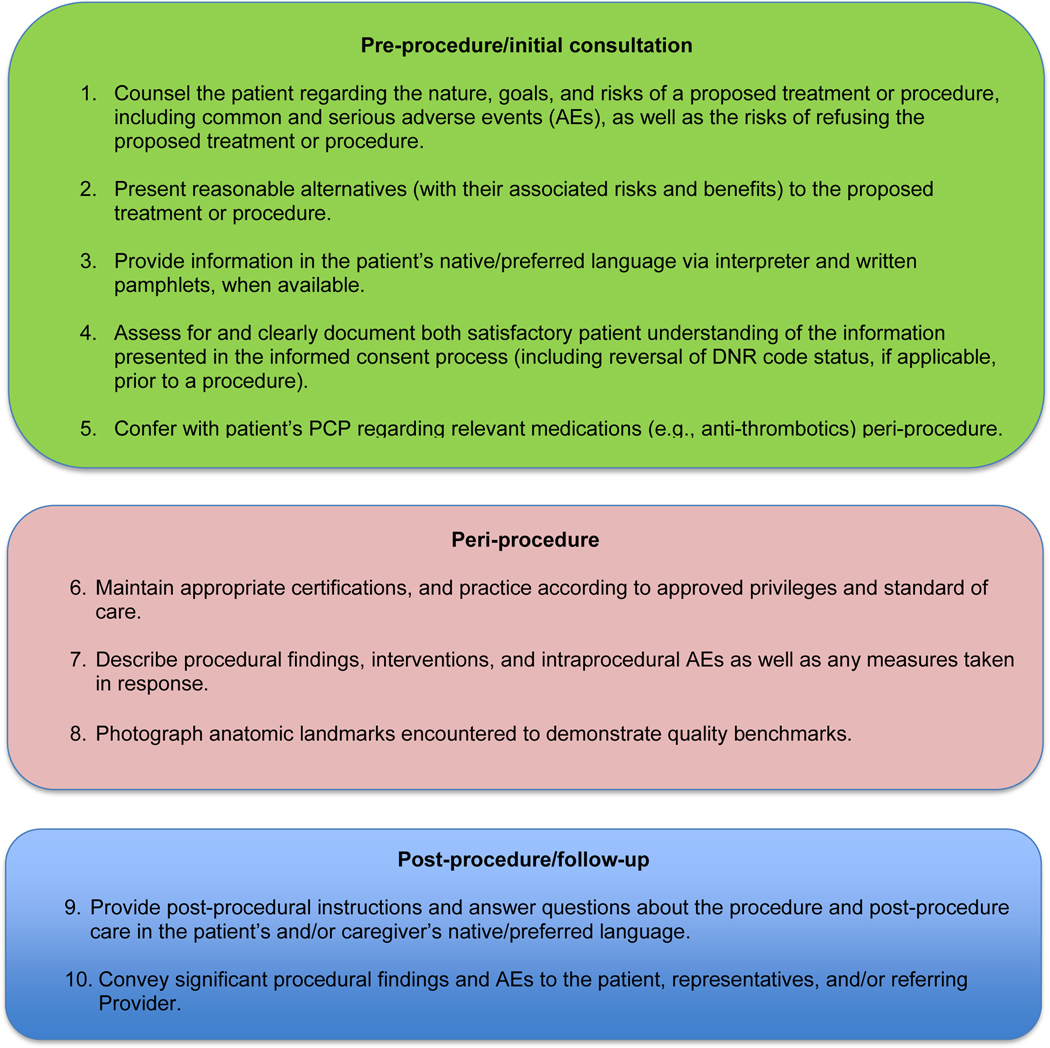

MPL claims may be made not only on the grounds of inadequately informed consent but also inadequately informed refusal. (5,13,14). While standards for adequate informed consent vary by state, most states apply the “reasonable patient standard,” i.e., providing an average patient with enough information to be an active participant in the medical decision-making process. Generally, informed consent should ensure: i) the patient understands the nature of the procedure/treatment being proposed, ii) discussion of the risks and benefits of undergoing and not undergoing the procedure/treatment, iii) presentation of reasonable alternatives, iv) discussion of the risks and benefits associated with these alternatives, and v) assessment of the patient’s comprehension of a-d (15) (Figure 1). Additionally, informed consent should be tailored to each patient and GI procedure/treatment on a case-by-case basis in lieu of a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, documentation of the patient’s understanding of the (tailored) information provided can concurrently improve quality of the consent and potentially decrease MPL risk (16) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MPL risk reduction pearls. *Whenever possible, documentation of the above-mentioned pearls is advisable.

Endoscopic procedures

Procedure-related MPL claims represent approximately 25% of all GI-related claims (8,17). Among these, 52% involve colonoscopy, 16% endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and 11% esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) (8). Albeit generally safe, colonoscopy, as with EGD, is subject to rare but serious AEs (18,19). Risk of these AEs may be accentuated in certain scenarios (e.g., severe colonic inflammation, coagulopathy), and as discussed earlier, may merit tailored informed consent. Regardless of the procedure, in the event of post-procedural development of signs/symptoms (e.g., tachycardia, fever, chest or abdominal discomfort, hypotension) indicating a potential AE, stabilizing measures and evaluation (e.g., bloodwork, imaging) should be undertaken, and hospital admission (if not already hospitalized) should be considered until discharge is deemed safe (19).

ERCP-related MPL claims, for many years, have had the highest average compensation of any GI procedure (20). Though discussion of advanced procedures is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning the observation that a majority of such claims involve an allegation that the procedure was not indicated (e.g., based on inadequate evidence of pancreatobiliary pathology) (21) or was for diagnostic purposes (e.g., in lieu of non-invasive imaging) rather than therapeutic (22–24). This emphasizes the importance of appropriate procedure indications (also discussed further below).

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement merits special mention given it can be complicated by ethical challenges (e.g., surrogate decision-maker consent, medical futility) and has a relatively high potential for MPL claims. PEG placement carries a low AE rate (0.1–1%), but these AEs may result in high morbidity/mortality, in part due to the underlying comorbidities of patients needing PEG placement (25,26). Also, timing of a patient’s demise may coincide with PEG placement, thus prompting (unfounded) perceptions of causality (25–27). Thus, such scenarios merit unique additional pre-procedure safeguards. For instance, for patients lacking capacity to provide informed consent, especially when family members may differ on whether PEG should be placed, it is advisable to ask the family to select one surrogate decision-maker (if no advance directive) to whom the gastroenterologist should discuss: i) the risks, benefits, and goals of PEG placement in the context of the patient’s overall clinical trajectory/life expectancy and ii) the need for consent (or refusal) based on what the patient would have wished. In addition, having a medical professional witness this discussion may be useful (28).

Anti-thrombotic agents

Peri-procedural management of anti-thrombotics, including anti-coagulants and anti-platelets, can pose challenges for the gastroenterologist. While clinical practice guidelines exist to guide decision-making in this regard, the variables involved may extend beyond the expertise of the gastroenterologist (29). For instance, in addition to the procedural risk for bleeding, the indication for anti-thrombotic therapy, risk of a thrombotic event, duration of action of the anti-thrombotic, and available bridging options should all be considered (29,30). While requiring more time on the part of the gastroenterologist, the optimal peri-procedural management of anti-thrombotic agents would usually involve discussion with the provider managing anti-thrombotic therapy to best conduct a risk-benefit assessment regarding if (and how long) it should be held (Figure 1). This shared decision-making, also involving the patient, may help decrease MPL risk and improve outcomes.

PROVIDER DEFENSIVE MECHANISMS MAY INCREASE MPL RISK

Physicians may engage in various defensive behaviors in an attempt to mitigate MPL risk; however, these behaviors may, paradoxically, increase risk (31,32).

Assurance behaviors

Assurance behaviors refer to the practice of recommending or performing additional services (e.g., medications, imaging, procedures, and referrals) that are not clearly indicated (2, 31,32). Assurance behaviors are driven by fear of MPL risk and/or missing a potential diagnosis. Recent studies have estimated that >50% of gastroenterologists worldwide have performed additional invasive procedures without clear indications and that nearly one-third of endoscopic procedures annually have questionable indications (31,33). While assurance behaviors may seem to decrease MPL risk, overall, they may inadvertently increase AE and MPL risk as well as healthcare expenditures (3,31,33).

Avoidance behaviors

Avoidance behaviors refer to providers avoiding participation in potentially high-risk clinical interventions (e.g., procedures), including those for which they are credentialed/certified proficient (31,32). Two real-world clinical scenarios that illustrate this behavior are: 1) an advanced endoscopist credentialed to perform ERCP referring a “high-risk” elderly patient with cholangitis to another provider to perform said ERCP or for percutaneous transhepatic drainage (in the absence of a clear benefit to such), and 2) a gastroenterologist referring a patient to interventional gastroenterology for resection of a large polyp, even though gastroenterologists are usually proficient in this skill and may feel comfortable performing the resection. Avoidance behaviors are driven by a fear of MPL risk and can have several negative consequences (34). For example, patients may not receive indicated interventions. Additionally, patients may have to wait longer for an intervention because they are referred to another provider, which also increases potential for loss to follow-up (2,31,32). This may be seen as constituting non-compliance with the standard of care, among other hazards, thus increasing MPL risk.

DOCUMENTATION TENETS

Thorough documentation can decrease MPL risk, especially since it is often used as legal evidence (16). Documenting, for instance, pre-procedure discussion of potential AEs (e.g., bleeding, perforation), risk of procedural failure (e.g., missed lesions), and medication/sedation-related AEs can protect gastroenterologists (16) (Figure 1). While, as discussed previously, these should be covered in the informed consent process (which indeed confers MPL protection), proof of compliance in providing adequate informed consent must come in the form of documentation (e.g. in the pre-procedural history and physical or in the procedure report) indicating that the process took place and specifically what topics were discussed therein. MPL risk may be further decreased by documenting steps taken during a procedure and anatomic landmarks encountered to offer proof of technical competency and compliance with standards of care (16,35) (Figure 1). In this context, it is worth recollecting the adage, “If it’s not documented, it did not occur.”

Also germane here is the topic of whether or not documentation is needed for “curbside consults.” The uncertainty is, in part, semantic; that is, at what point does a “curbside” become a consultation? A curbside is a general question or query (e.g., one that may also be answered by an internet or other reference search) in response to which information is provided; once it involves provision of medical advice for a specific patient (e.g., for whom identifiers have been shared and the electronic health record accessed), it constitutes a consultation. Based on these definitions, a curbside need not be documented, whereas a consultation—even if seemingly trivial—should be.

Consideration of language and cultural factors

Language barriers should be considered when the gastroenterologist is communicating with the patient, not only during the consent process but when obtaining a history, providing post-procedure instructions, and during follow-ups. To this end, 24/7 telephone interpreter services may assist the gastroenterologist (when communicating with non-English speakers and not medically certified in the patient’s native/preferred language) and strengthen trust in the provider-patient relationship (36). Additionally, native/preferred language written materials (e.g., consent forms, procedural information) should be provided, when available, to enhance patient understanding and participation in care (37) (Figure 1). Such efforts, whenever made, should be documented to best protect against MPL (16,37).

CHALLENGES POSED BY TELEMEDICINE

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly led to more virtual encounters. While increased utilization of telemedicine platforms may make healthcare more accessible, it does not lessen the clinician’s duty to the patient and may actually expose to greater MPL risk (18,38,39). Thus, the provider must be cognizant of two key principles to mitigate MPL risk in the context of telemedicine encounters. First, the same standard of care applies to virtual and in-person encounters (18,38,39). Second, patient privacy and HIPAA regulations are not waived during telemedicine encounters, and breaches of such may result in an MPL claim (18,38,39).

With regard to the first principle, for patients who have not been physically examined (e.g., those for whom an in-person clinic encounter was substituted by telemedicine), gastroenterologists should not overlook requesting timely pre-procedure anesthesia consultation or obtaining additional laboratory studies (e.g., CBC, INR), as needed, to ensure safety and the same standard of care. Moreover, particularly in the context of pandemic-related decreased procedural capacity, triaging procedures can be especially challenging. Standardized institutional criteria which prioritize certain diagnoses/conditions over others, leaving room for justifiable exceptions, are advisable.

VICARIOUS LIABILITY

Liability can extend to persons who have not committed a wrong but on whose behalf wrongdoers acted; this defines vicarious liability (40). Thus, gastroenterologists may be liable not only for their own actions but also for those of personnel they supervise (e.g., fellow trainees, non-physician practitioners) (40). Vicarious liability aims to ensure that systemic checks and balances are in place so that if failure occurs (e.g., in patient safety), harm can still be mitigated and/or avoided, as illustrated by Reason’s “Swiss Cheese Model” (41).

CONCLUSION

Any gastroenterologist may experience an MPL claim. Such an experience can be especially stressful and confusing to early-career clinicians, especially if unfamiliar with legal proceedings. Although MPL principles are not often taught in medical school or residency, it is important for gastroenterologists to be informed regarding tenets of MPL and cognizant of clinical situations which have relatively higher MPL risk. This can assuage untoward angst regarding MPL and highlight proactive risk mitigation strategies. In general, gastroenterologist practices that may mitigate MPL risk include effective communication, adequate informed consent/refusal, documentation of pre-procedure counseling, peri-procedure events, post-procedure recommendations, and maintenance of proper certification and privileging (Figure 1).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. All examples are hypothetical and aim to illustrate common clinical scenarios and challenges gastroenterologists may encounter within their scope of practice. The content herein should not be interpreted as legal advice for individual cases nor a substitute for seeking the advice of an attorney.

Conflict of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.www.mplassociation.org. Inside Medical Liability: Second Quarter 2020 Data Sharing Project Gastroenterology 2009–2018. Accessed on 06 Dec 2020.

- 2.Mello MM, Studdert DM, DesRoches CM. et al. Caring for patients in a malpractice crisis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(1):42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MA, Parul DP, Miller K, Rubenstein JH. MPL Claims Related to Esophageal Cancer Screening. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1348–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pegalis Stephen E., 1 Am. Law Med. Malp. § 3:2 (2005). Discoverable in the public record at local city halls and accessible on Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feld LD, Rubin DT, Feld AD. Legal Risks and Considerations Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Primer. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113(11):1577–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wight Sawyer v., 196 F. Supp. 2d 220, 226 (E.D.N.Y. 2002). Discoverable in the public record at local city halls and accessible on Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sita v. Long Island Jewish-Hillside Med. Ctr., 22 A.D.3d 743, 743–44, 803 N.Y.S.2d 112, 114 (2005). Discoverable in the public record at local city halls and accessible on Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conklin LS, Bernstein C, Bartholomew L, Oliva-Hemker M. Medical malpractice in Gastroenterology. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;6(6):677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(7):629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane K. Policy Research Perspectives Medical Liability Claim Frequency: A 2007–2008 Snapshot of Physicians. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez LV, Klyve D, Regenbogen SE. Malpractice claims for endoscopy. World journal of gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2013;5(4):169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and Characteristics of Paid Malpractice Claims Among US Physicians by Specialty, 1992–2014. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(5):710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kline Natanson v., 186 Kan. 393, 409, 350 P.2d 1093, 1106, decision clarified on denial of reh’g, 187 Kan. 186, 354 P.2d 670 (1960). Discoverable in the public record at local city halls and accessible on Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas Truman v., 27 Cal. 3d 285, 292, 611 P.2d 902, 906 (1980). Discoverable in the public record at local city halls and accessible on Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah P, Thornton I, Turrin D, et al. Informed Consent. [Updated 2020 Aug 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430827. [PubMed]

- 16.Rex DK. Avoiding and Defending Malpractice Suits for Postcolonoscopy Cancer: Advice from an Expert Witness. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;11(7):768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerstenberger PD, Plumeri PA. Malpractice claims in gastrointestinal endoscopy: analysis of an insurance industry data base. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1993;39(2):132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams MA, Allen JI. MPL in Gastroenterology: Understanding the Claims Landscape and Proposed Mechanisms for Reform. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;17(12):2392–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahlawat R, Hoilat GJ, Ross AB. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. [Updated 2020 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532268/ [PubMed]

- 20.Hernandez LV, Klyve D, Regenbogen SE. Malpractice Claims for Endoscopy. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013,5(4):169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotton PB. Analysis of 59 ERCP lawsuits; mainly about indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(3):378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotton PB. Twenty more ERCP lawsuits: why? Poor indications and communications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(4):904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamson TE, Tschann JM, Gullion DS, Oppenberg AA. Physician communication skills and malpractice claims. A complex relationship. The Western journal of medicine. 1989;150(3):356–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trap R, Adamsen S, Hart-Hansen O, Henriksen M. Severe and fatal complications after diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective series of claims to insurance covering public hospitals. Endoscopy. 1999;31(2):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Funaki B. Medical Malpractice Issues Related to Interventional Radiology Complications. Seminars in Intervetional Radiology. 2015;32(1):61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.www.nursinghome.millerandzois.com/feeding-tube-malpractice. Feeding Tube Nursing Home and Hospital Malpractice. Accessed on 20 Jun 2020.

- 27.www.lubinandmeyer.com/cases/sepsis_feeding_tube. Death of 82-year-old woman from sepsis due to improper placement of feeding tube. Accessed on 20 Jun 2020.

- 28.Brendel RW, Wei MH, Schouten R, et al. An approach to selected legal issues: confidentiality, mandatory reports, abuse and neglect, informed consent, capacity decisions, boundary issues, and malpractice claims. Medical Clinics of North America. 2010;94(1):1229–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee:, Acosta RD et al. The management of antithrombotic agents for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2016. Jan;83(1):3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saleem S, Thomas AL. Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding by an Internist. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2878. Published 2018 Jun 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Tanaka S, et al. Defensive medicine practices among gastroenterologists in Japan. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;12(47):7671–7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaheen NJ, Fennerty MB, Bergman JJ. Less is More: A Minimalist Approach to Endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(7):1993–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oza VM, Eli-Dika S, Adams MA. Reaching Safe Harbor. Legal Implications of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(2):172–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feld AD. Medicolegal implications of colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forrow L, Kontrimas JC. Language Barriers, Informed Consent, and Effective Caregiving. General Internal Medicine. 2017;32(8):855–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE, et al. Increased Access to Professional Interpreters in the Hospital Improves Informed Consent for Patients with Limited English Proficiency. General Internal Medicine. 2017;32(1):863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moses RE, McNeese L Feld LD, Feld AD. Social Media in the Health-Care Setting: Benefits but Also a Minefield of Compliance and Other Legal Issues. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109(8):1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabibian JH. https://www.guidepoint.com/category/legal-solutions-blog/. The Evolution of Telehealth. Accessed on 12 Aug 2020.

- 40.Feld AD. Malpractice risks associated with colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1641–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reason J. Human error: models and management. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(7237):768–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.