Abstract

To cope with the increasing healthcare costs brought about by the universal health insurance programme, national volume-based procurement (NVBP) was implemented in China to reduce drug prices. However, the impact of NVBP remains unknown. We reported the effects of the NVBP pilot programme on medication affordability and discussed the challenges and recommendations for further reforms. A total of 25 molecules won the bidding in the NVBP pilot programme, and price cuts ranged from 25% to 96%. Medication affordability was measured as the number of days’ wages needed to pay for a course of treatment, and the medication was identified as affordable if the cost of a treatment course was less than the average daily wage. After the NVBP, the proportion of affordable drugs increased from 33% to 67%, and the mean affordability improved from 8.2 days’ wages to 2.8 days’ wages. Specifically, for rural residents, the proportion of affordable drugs increased from 13% to 58%, and the mean affordability improved from 15.7 days’ wages to 5.3 days’ wages. For urban residents, the proportion of affordable drugs increased from 54% to 71%, and the mean affordability improved from 5.9 days’ wages to 2.0 days’ wages. Implementing the NVBP substantially improved medication affordability. In future reforms, a multifaceted approach addressing all issues in the health system is needed to enhance medicine access.

Keywords: health policy

Summary box.

On the completion of the pilot programme of national volume-based procurement (NVBP), huge price cuts have been achieved.

Implementing the NVBP has substantially improved the medication affordability for both rural and urban residents, whereas the data on quality and acceptability are still lacking.

A multifaceted approach addressing issues in every corner of health system is needed to enhance access to medicine.

Introduction

Access to medicines, including availability and affordability, remains one of the biggest health challenges faced by all countries.1 China, with the largest population in the world, is confronting unprecedented challenges in providing the necessary care for all citizens.2 In 2009, China launched a radical health reform with the ambitious goal of providing universal health coverage (UHC) to all citizens with equal access to basic healthcare.3 The health reform achieved success and has expanded the medical insurance coverage to 95% (or 1.34 billion) of the Chinese population in 2017. With regard to achieving UHC, healthcare spending increased rapidly at a nearly 20% annual growth rate, which was even faster than the growth of gross domestic product, resulting in wide concerns over the sustainability of the economy. In recent years, more efforts have been directed to contain the skyrocketing healthcare costs, particularly pharmaceuticals, which demonstrated a greater growth rate than other health sectors.4

After years of reforms attempting to lower drug prices,5 a novel pooled procurement, the national volume-based procurement (NVBP), was launched in November 2018 with the primary aim of reducing drug prices and improving the affordability of effective and safe medicines. Through transparent tendering and pooled procurement, in which a group of payers negotiates as one purchasing unit to establish collective bargaining power for procuring medicines at lower prices, a pilot programme of the NVBP, or the ‘4+7’ procurement reform, showed initial success in achieving huge price cuts, providing a potential solution for the critical health challenges faced by all.

To the best of our knowledge, no analysis has attempted to evaluate the impact of the NVBP on the affordability of medicines in the ‘4+7’ procurement reform. In this analysis, we reported the effects of the NVBP on medication affordability and discussed the challenges and recommendations for further reforms.

Overview of the NVBP

The ‘4+7’ procurement reform was piloted in four municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing) and seven key cities in other provinces (Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Xi’an, Dalian, Chengdu, Shenyang and Xiamen). Unlike previous procurement pilots, the ‘4+7’ reform, organised by the central government, received an unprecedented high political commitment. The Joint Procurement Office (JPO)—an alliance formed by representatives from local drug procurement agencies—was established under the supervision of the State Council. To address the persistent issues in the drug procurement and supply chain, the following unique measures have been attempted to achieve price cuts and improve medicine affordability with higher quality.

Ensure bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic drugs

To be listed for procurement, all generics were required to pass the Generic Consistency Evaluation (GCE), launched by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) in 2018.6 Historically, generic drugs were needed only for demonstrating comparable quality with the other marketed generic drugs, and the interchangeability between generic and brand-name drugs was unknown. Under the GCE’s criterion of ‘essential similarity’, however, generic drugs became equivalent to their corresponding brand-name drugs, improving generic competition and achieving better coordination of drug quality and pricing.

Achieve volume-price linkage to improve negotiation power

Previous price reforms failed to link bidding prices to procurement volumes. The NVBP, through ‘group purchasing’, enhanced the negotiation power of hospitals and payers to maximise the price reduction of drugs. The ‘4+7’ cities cover a total of 110 million citizens and account for 8.2% of the total 1.393 billion Chinese population, accounting for 20% of the Chinese drug market—the world’s second largest drug market.7

Promote drug supply chain efficiency

Since 2012, pioneering efforts in navigating effective approaches to enable greater efficiency in drug supply and provision have been implemented, but have resulted in a negligible impact on drug prices.7 The main problems in supply chains and procurement processes (eg, lack of transparency in drug-purchasing mechanisms, complicated drug distribution processes, low levels of marketisation, etc) have persisted and led to a continued rise in drug price.4

Encourage generic substitution and rational use of medication

The National Health Commission launched novel approaches to encourage non-proprietary prescription and utilisation of bid-winning drugs.8 To steer changes in prescribing behaviours, hospitals were incentivised for all cost-savings incurred by substituting the originators after completing the total quota defined in the procurement contract.

Reduce capital and marketing costs

The local payers, under the supervision of the National Healthcare Security Administration, paid 30%–50% prepayment to distributors to reduce their capital cost which amounted to 5%–15% due to long-term arrears with drug payment by public hospitals. As procurement volumes were guaranteed, marketing or promotional costs were also reduced, eventually lowering the final costs of bid-winning drugs.

Impact of the NVBP on the affordability of medicine

Improving medication affordability

We obtained the prices of the 25 drugs across the ‘4+7’ pilot cities from the JPO and Sunshine Medical Procurement All-In-One. Prior to the NVBP, there were vast variations in drug prices of the selected drugs manufactured by different drug companies. We used the lowest prices in the previous year in the 11 pilot cities as the baseline to obtain a more conservative estimate of their prices before the NVBP. As a part of the tendering procedures, the JPO collected the lowest prices for the selected drugs as the ceiling price, while the prices after the NVBP were the bid-winning prices that were obtained from Sunshine Medical Procurement All-In-One. A total of 25 drugs won the bidding in the pilot programme. One of these drugs lacked price information before NVBP, while the other 24 drugs had complete information either before or after NVBP. Additionally, 17 drugs were essential medicines listed on the China National Essential Medicine List (NEML).9

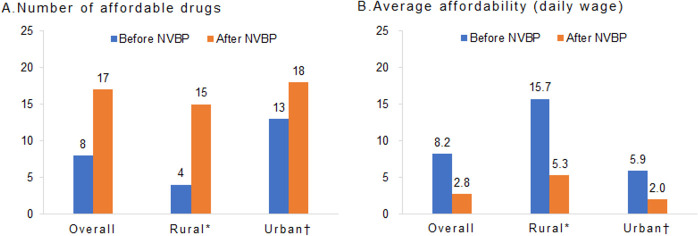

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, a drug used to treat chronic hepatitis B and HIV, had the largest price cut (96%), while levetiracetam had the lowest price cut (21%, figure 1). With the implementation of the NVBP, the long-existing disparities in the price of the selected drugs between China and other countries (eg, the USA) were reduced.10 A total of nine selected drugs in China were priced higher than those in the USA prior to the NVBP. After its introduction, only four selected drugs, mainly cardioprotective drugs (including atorvastatin and clopidogrel) and psychiatric medications (including escitalopram and levetiracetam) had a higher price in China than in the USA. Additional details on the drugs that won the bidding in the ‘4+7’ procurement reform before and after the NVBP and their price cuts are shown in the online supplemental appendix.

Figure 1.

Change in the medication price and affordability by therapeutic classes. *Included in China’s National Essential Medicine List. Data source: the current procurement prices were obtained from the Sunshine Medical Procurement All-In-One; previous lowest prices were obtained from the JPO. The average disposable annual salary was obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook 2019 (¥30 733 per capita). In 2019, China had 250 working days, and the overall disposable daily income per capita was ¥122.93. Classified according to the USP Therapeutic Categories Model Guidelines. According to the WHO, medication affordability was compared between the cost for a treatment course and the extra daily wages (EDWs) for the lowest paid unskilled government worker. Since EDW is not available in China, based on previous research, the average disposable daily income per capita was used. HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; JPO, Joint Procurement Office; NVBP, national volume-based procurement; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

bmjgh-2021-005519supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)

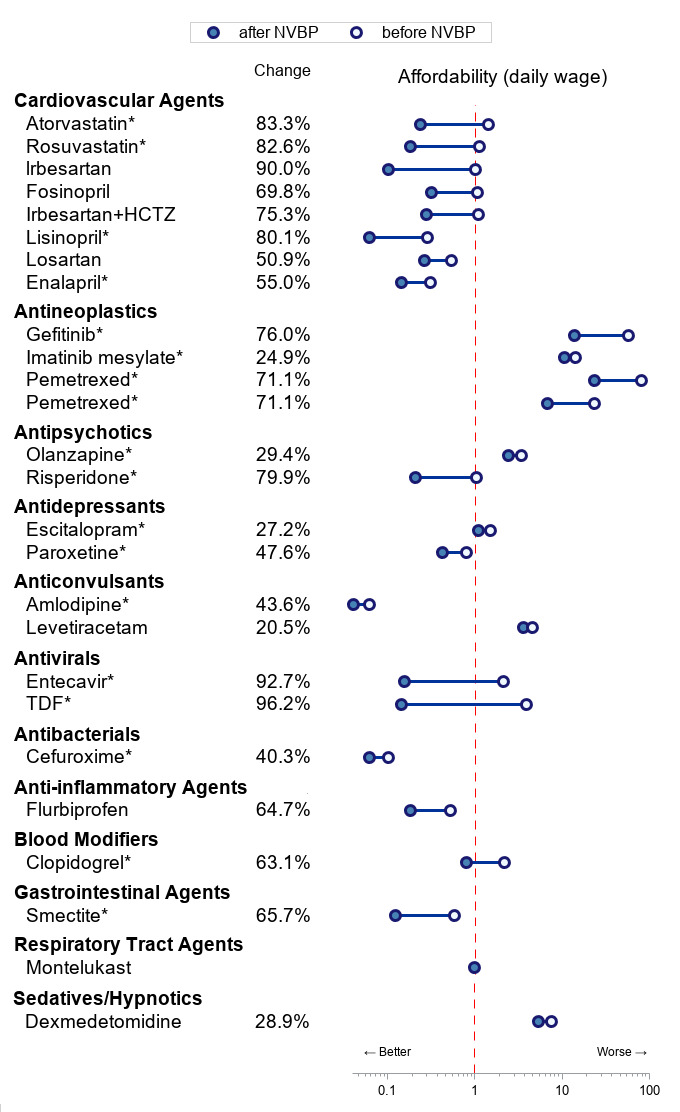

Medication affordability, measured by the number of days’ wages needed to pay for a course of treatment, improved substantially. According to the WHO/Health Action International,11 a medication is affordable if the cost of a treatment course is less than the daily wage of the lowest paid unskilled government worker. Following previous research,12–14 due to the lack of data, the daily wage of the lowest paid unskilled government worker (or ‘daily wage’) was proxied using the disposable annual income per capita for estimates. Specifically, based on the definition of wage rate15 and previous studies,16–18 we calculated the daily wage by dividing the average disposable annual income (¥30 733) by the working day (250 days) in China in 2019. Before the NVBP, 8 out of the 24 (33%) drugs with complete price information were priced lower than the daily wage.2 After the NVBP, 17 (71%) drugs became affordable (figure 2A). Overall, the mean affordability improved from 8.2 days’ wages before the NVBP to 2.8 days’ wages afterward (figure 2B). With the NVBP, the overall affordability of selected generic drugs was still higher than that of the USA (2.8 vs 1.8 days’ wages). Specifically, escitalopram and levetiracetam are affordable in the USA, but not in China. Several oncology drugs, including gefitinib and imatinib mesylate, are not affordable in China and the USA. Additionally, after applying 40% reimbursement offered by the UHC, the overall average affordability was 1.7 days’ wages in China. Additional details on affordability in the pilot programme are provided in the online supplemental appendix.

Figure 2.

Comparing medication affordability before and after the NVBP. (A) The number of drugs that was affordable for the individuals with average daily wage. (B) The mean affordability measured in the ability of daily wage to pay for a treatment course. *Disposable daily income per capita of all rural residents, ¥64.08. †Disposable daily income per capita of all urban residents, ¥170.16. NVBP, national volume-based procurement.

Mitigating rural–urban disparities in medication affordability

The NVBP demonstrated a more profound impact on rural residents than on those living in urban areas. In 2019, the daily wages of rural and urban residents were ¥64.08 and ¥170.16, respectively.2 For workers living in rural areas, the number of affordable drugs with complete price information increased by nearly four times from 4 (17%) to 15 (63%), and the mean affordability improved by three times from 15.7 days’ wages before the NVBP to 5.3 days’ wages afterward (figure 2). For urban residents, the proportion of affordable drugs increased by 30% from 13 (54%) to 18 (75%), and the mean affordability improved from 5.9 days’ wages to 2.0 days’ wages (figure 2).

Recommendations for future procurement

Through the NVBP, the well-coordinated ‘4+7’ procurement reform has achieved huge price cuts and reduced rural–urban disparities in medication affordability. Improving affordability of medicines requires a multifaceted approach in addressing issues in every dimension of the health system.19–21 However, drug prices and costs are still the main focus of procurement, and other aspects such as availability, acceptability and real-world quality have not been well addressed in the NVBP. As China commits to working towards the attainment of the UHC through dramatic healthcare reforms, the NVBP is continuously expanding, and three rounds of the tender have been completed by 2020. For future reforms, we provide the following recommendations for addressing the existing concerns:

Enhance drug quality and safety regulation

Although generics are required to pass the GCE to demonstrate pharmaceutical bioequivalence, they should be manufactured in compliance with the current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) to have as high a quality as brand-name drugs, as literature shows that there are still gaps in generic drug manufacturers’ compliance with the cGMP in China.22–24 The expansion of the NVBP has highlighted wider concerns regarding the safety and quality of generics, particularly, injectables that should meet the requirements of sterility testing and drugs with narrow therapeutic indices (eg, tricyclic antidepressants) that should maintain batch-to-batch consistency of potency. Hence, the NMPA should initiate frequent inspections for procured manufacturers to ensure the quality of drugs. Since full-scale clinical trials are not required for generics to be introduced to the market, post-marketing surveillance of generics and real-world inexpensive studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to monitor their safety.

Enhance physicians’ and patients’ acceptability of bid-winning drugs

With the procurement reforms, doubts over the bid-winning drugs were rising, especially among physicians and patients, given the huge price cuts. Previous studies indicated that physicians tended to believe that originator drugs were more effective or of higher quality than their generic versions.25 Moreover, patients prefer brand-name drugs because of their superior quality and efficacy. Even though incentives have been offered at the hospital and patient levels, more systematic approaches should be explored to boost public confidence in bid-winning generic drugs. Specifically, educational programmes targeting both prescribers and consumers can be provided to improve the acceptability of bid-winning drugs in a variety of ways, such as broad educational campaigns, signs or posters in pharmacies, and education sessions. Regarding medical insurance, different levels of co-payment between bid-winning and no-winning drugs may be used to promote the use of generic drugs.

Improve procurement efficiency

To maximise the price cuts, the lowest bidding price was compared with the lowest listing price on the procurement platform by the end of 2018 in the 11 pilot cities. The JPO then requested further price reduction if the bidding price was higher than it was in the past. However, the procurement price of dexmedetomidine was higher than the lowest trading price in the previous year, raising concerns over the efficiency of NVBP procurement. For future procurement, big data analytics, which thoroughly review historical drug prices and quantities from multiple sources, might be helpful in setting reasonable cap prices for NVBP drugs. It might be possible to establish comprehensive and dynamic health economic models, which include real-world data and evidence to evaluate the cost-effectiveness analysis to support price negotiations for procurement. Additionally, models for procurement-based budget impact analysis should be established to inform price negotiations from the national healthcare payers’ perspective.

Expand the coverage of the NVBP

In the pilot stage, only a few medications were included in the tender, while the affordability of other medications was still unclear. In the ‘4+7’ pilot programme, most included drugs were tablets, and only three were relatively expensive injectables. However, in the Chinese pharmaceutical market, more than 60% of shares are injectables.26 Therefore, including more injectables to further improve affordability among patients using the necessary products might be necessary. Additionally, the ‘4+7’ pilot programme included 10 cardiovascular drugs, and antidiabetic drugs were absent. Meanwhile, several diseases, including digestive, respiratory and musculoskeletal diseases, only had one drug that was within procurement. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the coverage range of more health conditions to improve the affordability among patients whose conditions are not yet covered and increase the variety of options covered under the NVBP for individual health conditions that will resolve patients’ acceptability/tolerability issues.

Focus on the value of medicine

To deliver safe and cost-effective medicines, systematic evaluation of the effectiveness, safety and economics is necessary but is currently lacking in the selection process of drugs included in the tender. The selection of procurement drugs is focused on the sales volume rather than the ‘value’ of medicine. With the recent launch of the National Health Technology Assessment (HTA) to bring evidence-based medicines to health decision-making, we expect to see more ‘high-value’ drugs selected for bidding. Currently, HTA has already been used for the selection of NEML drugs in China. As the NVBP continues to expand, paying more attention to the drugs on the NEML or with proven cost-effectiveness would be beneficial. Additionally, the HTA could serve as an effective tool for estimating drug prices used in other developed countries. For example, in the process of procurement of drugs listed in the NEML, HTA reports could be used to determine the cost-effectiveness of the drug, and a reasonable price range could also be determined by modifying the parameters of the reports.

Mitigate the risk of monopolies and anticompetitive behaviours

Even though the production capacity of drug companies is required, concerns over the security of drug supply chains still exist. The recent boom in pharmaceutical industry consolidation may drive small drug makers with inferior research and production capacity out of business, which is one of the initial objectives of the NVBP. Alternatively, the ‘winner-takes-all’ approach may create unexpected monopolies and anticompetitive behaviours, resulting in a big threat to patients’ access to care over the long run.27 A previous study comparing the prices before and after the NVBP in Shanghai showed that the prices of two drugs that exceeded a 50% market share increased after the NVBP, indicating that the contracted price after NVBP might be manipulated by the market power.19 Thus, strategies for eliminating the risks of monopoly (eg, splitting the procurement to at least three drug companies, adding drugs from the same therapeutic classes, etc) should be considered. Additionally, because we used the lowest prices obtained from JPO for the prices before the NVBP, the effects of NVBP might vary area-wise. Therefore, different areas should issue corresponding regulations according to the specific implementation situation in each area to avoid monopoly and improve affordability.

Conclusions

Access to medicines is a fundamental right according to the WHO, but many patients around the world are struggling to afford medications as drug prices are rising. Every individual should have equal access to the right medicines of high quality, at the right price and at the right place. As a part of healthcare reform towards the UHC, the NVBP, which was set to broaden access to medicines, has successfully led huge price cuts and improved affordability of medicines, especially for those with relatively lower wages. This is the first analysis to comprehensively review the innovative volume-based procurement model in China, providing invaluable insights for other nations or entities that are navigating ways to improve patients’ access to care.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Lei Si

JY and ZKL contributed equally.

Contributors: Authors have participated in the development and implementation of the national volume-based procurement (NVBP) in China. JY is a pharmacist by training who specialises in pharmaceutical policies. ZKL is a health economist who conducted a range of projects evaluating the economic burdens associated with medications in the USA. XX is a PhD candidate who specialises in health economics and pharmacoeconomics. BJ is an expert on pharmaceutical regulation and procurement who has worked closely with the Division of Pharmaceutical Pricing and Procurement, National Healthcare Security Administration and the Joint Procurement Office (JPO) of the NVBP, to monitor the impacts of the NVBP. JY, ZKL and BJ conceived of the work and made substantial contributions to the analysis. JY, ZKL and BJ wrote the draft of the manuscript. JY, ZKL, XX and BJ revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Standfirst: The national volume-based procurement (NVBP), the new pooled procurement using collective bargaining power to negotiate drug prices, has substantially improved patients’ affordability of essential medicines in China, say JY, ZKL, XX and BJ.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Morgan SG, Bathula HS, Moon S. Pricing of pharmaceuticals is becoming a major challenge for health systems. BMJ 2020;368:l4627. 10.1136/bmj.l4627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.China Yearbooks . China statistical Yearbook 2019 2019.

- 3.Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in universal health coverage. Lancet 2019;394:1192–204. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang M, He J, Chen M, et al. "4+7" city drug volume-based purchasing and using pilot program in China and its impact. Drug Discov Ther 2019;13:365–9. 10.5582/ddt.2019.01093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan K, Yang C, Zhang H, et al. Impact of the zero-mark-up drug policy on drug-related expenditures and use in public hospitals, 2016-2018: an interrupted time series study in Shaanxi. BMJ Open 2020;10:e037034. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(NDA) TCNDA . Opinions on the evaluation of the consistency of quality and efficacy of generic drugs, 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-03/05/content_5049364.htm [Accessed 20 Dec 2020].

- 7.Yue X. “4+7” Drug procurement reform in China, 2019. Available: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/CGD-procurement-background-china-case.pdf [Accessed 20 Dec 2020].

- 8.(NHC) NHC . The Notice on the Use of the Drugs for the "4+7" National Pilot on the Centralized Drug Procurement, 2019. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7659/201901/628ac5004d244af7ad53c0b109f0c2df.shtml [Accessed 20 Dec 2020].

- 9.(NHC) NHC . The notice on the release of the National essential medicine list (NEML), 2018. Available: http://www.gov.cn/fuwu/2018-10/30/content_5335721.htm [Accessed 20 Dec 2020].

- 10.Hu S, Zhang Y, He J, et al. A case study of pharmaceutical pricing in China: setting the price for Off-Patent Originators. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2015;13 Suppl 1:13–20. 10.1007/s40258-014-0150-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raju PKS. WHO/HAI Methodology for Measuring Medicine Prices, Availability and Affordability, and Price Components. In: Vogler S, ed. Medicine price surveys, analyses and comparisons. Academic Press, 2019: 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu G, Gong S, Cai H, et al. The availability, price and affordability of essential antibacterials in Hubei Province, China. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:1013. 10.1186/s12913-018-3835-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong S, Wang Y, Pan X, et al. The availability and affordability of orphan drugs for rare diseases in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:20. 10.1186/s13023-016-0392-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diao Y, Qian J, Liu Y, et al. How government insurance coverage changed the utilization and affordability of expensive targeted anti-cancer medicines in China: an interrupted time-series study. J Glob Health 2019;9:020702. 10.7189/jogh.09.020702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garofalo L, Di Giuseppe G, Angelillo IF. Self-medication practices among parents in Italy. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:580650. 10.1155/2015/580650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolovic E, Riederer F, Szucs T, et al. Self-reported headache among the employees of a Swiss university hospital: prevalence, disability, current treatment, and economic impact. J Headache Pain 2013;14:29. 10.1186/1129-2377-14-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46:398–412. 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small GW, McDonnell DD, Brooks RL, et al. The impact of symptom severity on the cost of Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:321–7. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills A. Resilient and responsive health systems in a changing world. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:iii1–2. 10.1093/heapol/czx117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wirtz VJ, Kaplan WA, Kwan GF, et al. Access to medications for cardiovascular diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Circulation 2016;133:2076–85. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.008722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simão M, Wirtz VJ, Al-Ansary LA, et al. A global accountability mechanism for access to essential medicines. Lancet 2018;392:2418–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32986-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Li S. Drug policy in China. Transformations, current status and future prospects. Pharmacoeconomics 1997;12:1–9. 10.2165/00019053-199712010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang B, Barber SL, Smid M, et al. Technical gaps faced by Chinese generic medicine manufacturers to achieve the Standards of who medicines prequalification. J Generic Med 2013;10:14–21. 10.1177/1741134313483748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong H, Ouyang D. The gap analysis between Chinese pharmaceutical academia and industry from 2000 to 2018. Scientometrics 2020;122:1113–28. 10.1007/s11192-019-03313-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou X, Zhang X, Yang L, et al. Influencing factors of physicians' prescription behavior in selecting essential medicines: a cross-sectional survey in Chinese County hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:980. 10.1186/s12913-019-4831-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huaxi Securities Research Institute . As consistency evaluation of injectables landed, the generic drug market is again a big change. Available: http://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202005151379773285_1.pdf [Accessed 05 Jun 2021].

- 27.van Valen M, Jamieson D, Parvin L, et al. Dispelling myths about drug procurement policy. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e609–10. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30190-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-005519supp001.pdf (95.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.