Abstract

Introduction.

This study examined the relations between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their assertive and submissive responses to peer victimization. The mediating role of children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior in the association between their temperamental shyness and responses to peer victimization in school settings was assessed, as well as the moderating effect of observed maternal praise.

Method.

Mothers of 153 Chinese American children (46.4% boys; Mage = 4.40 years, SDage = 0.79 years) reported on their children’s temperamental shyness, and teachers rated children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior and responses to peer victimization. Mothers’ use of praise during their interactions with children in a free-play session was observed.

Results.

Children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior played a mediating role in the associations between their temperamental shyness and responses to peer victimization. Moreover, maternal praise moderated the relation between children’s temperamental shyness and anxious-withdrawn behavior, such that more temperamentally shy children with mothers who used praise more frequently displayed less anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn, was associated with more assertiveness and less submissiveness in response to peer victimization.

Conclusions.

These findings highlight the importance of maternal praise in reducing children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn facilitates their capacity to cope with peer victimization.

Keywords: temperamental shyness, anxious-withdrawn behavior, responses to peer victimization, maternal praise, Chinese American children

Peer victimization during early childhood has detrimental short- and long-term ramifications for children’s school adjustment, mental health, and psychosocial development (e.g., Krygsman & Vaillancourt, 2019; Kochnderfer & Ladd, 1997). How children respond to peer victimization can either enhance or mitigate the risk of future peer victimization and maladjustment (e.g., Ostrov, Kamper, Hart, Godleski, & Blakely-McClure, 2014). Some patterns of victimization experienced by young children may be tied to individual traits that are behaviorally manifested in how they engage with peers (Perry, Meisel, Stotsky, & Ostrov, 2020). Temperamental shyness is one such childhood characteristic that may have implications for how children respond to aggression enacted against them by peers. It is a natural precursor of observable, anxious-withdrawn behavior in social interactions (Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). Recent findings indicate that Chinese American preschooler’s temperamental shyness is associated with less assertiveness as mediated by their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior in peer group interactions (Balkaya, Cheah, Yu, Hart, & Sun, 2018). This connection between shyness and anxious withdrawal may also play out in less assertive and more submissive responses to peer victimization. Maternal praise has been found to be an important factor in reducing anxiety and inhibition in preschool-age children (e.g., Lau, Rappee, & Coplan, 2017). Accordingly, the present study examines the potential moderating role of observed maternal praise in attenuating more temperamentally shy children’s expressions of anxious-withdrawn behavior in its plausible associations with more and less adaptable reactions to victimization by peers.

Peer Victimization in Early Childhood

Peer victimization during the early childhood years has been conceptualized according to age-related differences in how aggression is perceived by younger versus older children (Monks & Smith, 2006; Vlachou, Botsoglou, & Andreou, 2013). It has generally been operationalized for younger children as being the recipient of hostile/aggressive behavior (e.g., Alsaker & Valkanover, 2002; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997). Children can be subjected to many forms of aggression during early childhood (Monks et al., 2005; Yu, Cheah, Hart, Yang, & Olsen, 2019). Although the use of physical aggression (e.g., hitting, pushing, taking away an object, physically threatening) declines after 3 years of age and on into the elementary school years, it is a common form of hostility that three-to-five-year-old children are often subjected to (e.g., Côté, Vaillancourt, LeBlanc, Nagin, & Tremblay, 2006).

Preschool-age children can also be targeted for relational aggression, which is conceptualized as harming others through exclusion, spreading rumors, and withdrawing friendship or threatening to do so (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). This form of hostility has been observationally measured as early as 2.5 years of age (Crick et al., 2006) and is typically enacted by younger children in response to immediate problems in simple and direct ways (e.g., I won’t be your friend anymore unless you give me that crayon), evolving into a somewhat limited use of more sophisticated strategies as exemplified by rudimentary gossiping, secret telling, and nasty rumor spreading as children progress through the early childhood years (e.g., Casas & Bower, 2018). Other hurtful behaviors that preschool-age children are confronted with include verbal disparagements such as name calling, teasing, and derogatory or embarrassing remarks that can be accompanied by nonverbal, demeaning expressions (e.g., McNeilly-Choque, Hart, Robinson, Nelson & Olsen, 1996).

Most children regularly experience multiple forms of peer aggression to greater or lesser extents during their early childhood years (e.g., Vlachou, et al., 2013). For example, Kochenderfer and Ladd (1996) reported that “over 75% of kindergarten children reported experiencing some level of peer aggression” during each of two several-week Fall and Spring assessment periods while attending school. Similarly, 72% of kindergarten children in a study conducted by Alsaker & Valkanover (2002) nominated themselves very often as peer bullying victims. Young children’s self-reports of victimization have also been corroborated by observer’s ratings of children’s exposure to various forms of peer aggression (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997) that often co-occur in early childhood (Blakely-McClure & Ostrov, 2018).

Bullying can be manifest as any of the aforementioned forms of aggression and is considered to be a subtype of aggressive behavior that is enacted with an intent to physically or psychologically harm less powerful individuals repeatedly over time (e.g., Vlachou, et al., 2013). However, bullying has appeared in past research to be less applicable to preschool-age children. Relative to middle childhood and adolescence, younger children do not attend as well to repetition, power imbalance, and the aggressors’ intent, all of which comprise primary features of bullying behavior that are typically associated with peer victimization (e.g., Monks & Smith, 2006; Alsaker & Valkanover, 2002; Vlachou et al., 2013). For example, they have difficulty distinguishing aggressive conflicts between peers of equal strength from power imbalances that are typical of bullies who aggressively prey persistently on weaker children, thus conflating bullying and aggression (Monks & Smith, 2006). Early childhood teachers have difficulty making this differentiation as well and are prone to confound bullying and general aggressive behavior when considering how much children are recipients of hostile/aggressive behavior on early childhood bully/victim measures (e.g., Alsaker & Valkanover, 2002).

However, there is still much to be learned about the viability of the bullying construct in early childhood amidst findings that contradict the conclusions noted above and raise new questions. For example, recent research has demonstrated that when the conceptual distinction between bullying and aggression is well specified in developmentally appropriate instrumentation, early childhood teachers and preschool-age children have reliably identified physical, relational and verbal bullying behavior and associated peer victimization subtypes (e.g., Ostrov, Kamper-DeMarco, Blakely-McClure, Perry, & Mutignani, 2019; Vlachou, et al., 2013). Accordingly, several studies have shown that bullying involving likely victim perceptions of power imbalance in the context of unwanted, repeated aggressive acts does occur during early childhood (e.g., Aksaker & Valkanover, 2002; Monks et al., 2005; Ostrov et al., 2019). However, available evidence also indicates that most young children tend to be victimized for brief periods of time and do not experience extended, proactive, and repeated victimization by the same peers (e.g., Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997; Monks & Smith, 2006).

Regardless of the type of aggression by which young children are victimized, each is viewed as emotionally distressing in preschooler’s perceptions of harmfulness (e.g., Crick, Ostrov, Appleyard, Jansen, & Casas, 2004) and is typically viewed by preschoolers as general aggression (Vlachou, et al., 2013). Further, although statistically distinguishable, the correlations involving observed and teacher rated physical and relational bullying and general physical and relational aggression are relatively high in early childhood (Ostrov et al., 2019). Different forms of peer-initiated aggression that preschool-age children are victimized by are also highly correlated and have been found to coalesce into a single, measurable general aggression construct when rated by teachers (Yu et al., 2019). Accordingly, given the significant statistical overlap in aggression constructs, our study focused on teacher perceptions of child responses to aggressive behavior in general, without specifying various peer victimization subtypes which was beyond the scope of this investigation (cf. Godleski, Kamper, Ostrov, Hart, & Blakely-McClure, 2015; Kamper-DeMarco & Ostrov, 2017).

It has been posited that preschool and kindergarten teachers are more aware of peer victimization problems due to higher teacher-child ratios relative to grade schools and their greater emphasis on socialization (Alsaker & Valkanover, 2002), even though the overlap between teacher reports and direct observations of peer victimization is not always consistent, perhaps due to limited observation sampling time (Krygsman & Vaillancourt, 2019). Given the prevalence of peer victimization in early childhood settings noted earlier, we anticipated that teachers in our sample with ample exposure to and more direct oversight of children’s social interactions would be tuned into salient ways that individual children respond to aggressive peer provocations (e.g., angrily retaliating, crying, cowering, withdrawing to a corner of the classroom, and assertive reactions).

Temperamental Shyness, Anxious Withdrawal, and Responses to Peer Victimization

Temperamental shyness is a dispositional characteristic of fearful and inhibited reactivity to unfamiliar social situations that emerges very early in life and is moderately stable over time (Rapee & Coplan, 2010). Previous studies have shown that shy Chinese children are at a greater risk for being victimized by their peers (e.g., Liu et al., 2019). As shy preschoolers realize their difficulties in social functioning, they may develop negative self-perceptions of their social skills, including lower self-esteem and self-perceived peer acceptance (e.g., DiBiase & Miller, 2015). Such negative self-perceptions may lead them to withdraw from social situations and thus, limit their opportunities to develop abilities to socially assert themselves with peers (Nelson, Hart, Evans, Coplan, Roper, & Robinson, 2009). Although a direct linkage between shyness and observed assertiveness with peers was not found in a recent study of preschoolers by Acar, Rudasill, Molfese, Torquati, & Prokasky (2015), an indirect association involving anxious-withdrawn behavior as a mediator was recently discovered by Balkaya and colleagues (2018) in a sample of Chinese American preschoolers. More temperamentally shy children who displayed more anxious-withdrawn behavior were found to be less assertive with peers and had more negative social adjustment outcomes including more exclusion by peers.

Anxious-withdrawn behavior is characterized by the frequent display of nervous, fearful, solitary, and socially reticent behavior when interacting with potential social partners, which appear to be linked to temperamental and physiological factors (Rubin et al., 2009). Despite the strong overlap between the definition and features of temperamental shyness and anxious-withdrawn behavior, temperamental shyness is considered to be a precursor of anxious-withdrawn behavior (Henderson & Zimbardo, 1998). Temperamentally shy and inhibited children tend to display anxious-fearful and anxious-withdrawn behavior with peers (Balkaya, et al., 2018; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002), which in turn may increase their risk for peer rejection, victimization, and internalizing problems (e.g., Perry et al., 2020).

In demanding peer situations, anxious-withdrawn children tend to generate fewer solutions for social problems and be less assertive than non-withdrawn children. For example, Stewart and Rubin (1995) found that children who exhibited shy and anxious-withdrawn behavior displayed fewer social problem-solving initiations and socially assertive strategies compared to their more sociable peers. Thus, shy children who engage in anxious withdrawal are less assertive compared to their more sociable counterparts. In addition, Stewart and Rubin (1995) suggested that withdrawn children can be viewed as being more submissive and wary during peer interactions.

Less assertive and more submissive behavior associated with anxious-withdrawn behavior that might stem from temperamental shyness may play a significant role in how children respond to peer victimization and therefore is a primary focus of this study. Young children employ a variety of reactions and coping strategies when they are victimized by peers. These include angrily retaliating (provocative victims), crying, sulking, cowering, withdrawing from provocations, teasing, adult seeking, avoiding the perpetrator, and actively resisting by responding calmly and firmly when expressing opposition to a provocation or defending their position in nonaggressive ways (e.g., Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992; Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2004; Olweus, 1993; Reunamo, Kalliomaa, Repo, Salminen, Lee, & Wang, 2015).

Regarding submissive responses in the aforementioned list that are more typical of anxious withdrawn children, passive victims who respond in this manner to aggressive provocations by cowering, crying, or seeking to immediately withdraw from provocative interactions do little to deter future victimization. They make themselves easy targets for future provocations due to little risk of retribution for the perpetrators (e.g., Olweus, 1993; Rubin et al., 2009). Alternatively, children who actively resist aggressive provocations and confidently stand up for themselves in non-aggressive ways by telling an aggressor to leave them alone, or to stop what they are doing are generally more successful at deterring future victimization (e.g., Olweus, 1993).

No study we are aware of has examined whether children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior mediates the association between their temperamental shyness and their responses to peer victimization during early childhood. Based on the aforementioned research with Chinese American children, we anticipated that more temperamentally shy children in our sample would be more likely to behave in an anxious-withdrawn manner in the presence of peers. Less temperamentally shy children would be more likely to display less anxious withdrawal. This, in turn, would be associated with children exhibiting more anxious-withdrawn behavior responding more submissively to aggressive peer provocations, and with children displaying less anxious-withdrawn behavior utilizing more assertive strategies in handling aggressive behavior directed towards them.

Chinese American Cultural Considerations

Various studies have shown that Asian American children are bullied more frequently compared to their non-Asian American peers because they may look, dress and talk differently (e.g., Hong et al., 2014). Their peer group social functioning can also be different which may lend itself to more peer victimization. Shy, sensitive, and socially restrained group-dependent behaviors have long been emphasized in traditional Chinese cultures to achieve social order and harmony. This kind of inhibited behavior is interpreted to reflect a reserved and respectful disposition in Chinese cultural settings and is still valued to some extent despite dramatic societal, social, and economic changes over the past several decades that have led to the incorporation of many Western values (e.g., Chen & Chen, 2012). However, inhibited behaviors are considered to be less socially adaptive in North American settings due to a greater emphasis on individual assertiveness, social initiative, and expressiveness (e.g., Rubin et al., 2009). This contrast may pose significantly more challenges for temperamentally shy immigrant Chinese children who are more limited in their ability to behaviorally adapt in expressive, outgoing ways to the North American peer group culture due to social fear and anxiety.

The Role of Parenting: Maternal Praise

Based on previous findings described above, we conceptualized and examined the relations between temperamental shyness and responses to peer victimization through children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. Further, we determined that the moderating role of maternal parenting in these associations would be important to explore. Several studies have demonstrated a positive association between maternal praise and Asian and Asian American children’s socio-emotional and behavioral outcomes (Seo, Cheah, & Hart, 2017; Shinohara et al., 2012). Nevertheless, little attention has been devoted to examining the role of maternal praise on Chinese American children’s social adjustment, especially with regard to their responses to peer victimization.

A growing body of research indicates that positive, warm, and encouraging parenting practices may provide a buffer for shy children, decreasing the tendency for children who are shy to experience later maladjustment. For instance, Grady and Karraker (2014) found that positive verbal encouragement that involved suggesting behaviors that facilitated positive interaction with playmates reduced anxious-withdrawn behavior in shy children. Recent findings also showed that when Chinese immigrant mothers encouraged their children to exhibit more modest, humble, and conforming behavior to help them better fit in with other children, more temperamentally shy children were less likely to behave in an anxious-withdrawn manner in the presence of their peers, which in turn was associated with less peer exclusion and greater assertiveness skills (Balkaya et al., 2018).

Maternal praise is another feature of positive, warm, and encouraging parenting which may functionally serve to reduce social fear and promote general confidence and more self-assurance in navigating peer group situations. Maternal praise refers to mother’s positive evaluations of children’s products, performances, or attributes and is different from simple acknowledgement and feedback (Henderlog & Lepper, 2002). Praise is an important component of parental warmth and has positive effects on the development of children’s social competence (Shinohara et al., 2012), including assertive behavior and prosocial orientations (Hart, Newell, & Olsen, 2003).

Published research thus far suggests that maternal praise can help reduce social fear and anxiety. For example, Van Zalk and Kerr (2011) examined the link between shy adolescent’s parental emotional warmth and social fears. Specifically, the authors found that shy and socially fearful adolescents might benefit from praise offered by their parents. Parental demonstrations of warmth through their use of praise that involved compliments as well as warm gestures marginally reduced shy adolescent’s display of social fear during interactions with others. However, the challenge with ascertaining the independent effects of praise on the reduction of social fear in children is that praise and encouragement is usually included in an array of other positive, warm, and nurturing parenting practices. An aim of the current study is to ascertain whether this kind of reduction in social fear due to parental praise alone may in turn decrease submissive behaviors in younger children and increase assertiveness in response to peer victimization as children’s overall self-assurance is enhanced.

Maternal praise has also been considered an important component of parent intervention programs specifically designed to reduce social fear and anxiety in preschoolers (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2017). For example, the Cool Little Kids program involving parent-education sessions that includes a component where parents are coached to engage in frequent praise of children’s social initiations (along with other positive parenting features such as reducing overprotection) has been proven to be effective in reducing anxiety and inhibition in preschool-aged children (Lau et al., 2017). Likewise, the Turtle Program developed by Chronis-Tuscano and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that parents’ labeled praise for preschooler’ approach behaviors (along with other positive parenting practices such as encouraging appropriate social behaviors) decreased their anxiety and inhibited behaviors and increased their observed initiations with peers in school contexts. Together with other positive parenting components, parental praise is likely an important factor that contributes to diminished socially inhibited behaviors and anxiety in early childhood. In accordance with the above mentioned aim of examining the contribution of maternal praise to the reduction of submissiveness and an increase in assertiveness in peer victimization circumstances, we also considered the contribution of observed maternal praise in isolation from other aspects of positive, warm parenting practices in determining whether it is associated with a reduction in anxious-withdrawn behavior for children who are more temperamentally shy.

From a cultural perspective, parenting beliefs and practices like praise and its consequences are grounded in cultural values (Cheah, Li, Zhou, Yamamoto, & Leung, 2015). Traditionally, mothers in Confucian-based cultural context are discouraged from using praise (Kim & Hong, 2007). In Chinese culture, humility and modesty is deeply rooted in social history and philosophy, and praise is thought to contribute to children’s self-contentedness and pride (Huang & Gove, 2012). Such internalized Chinese cultural values may lead mothers to consider praise to be harmful to a child’s character if given too often (Salili, 1996). Indeed, Chinese immigrant mothers have been found to use less praise than European American mothers (e.g., Cheah et al., 2015). However, praise is still considered to be beneficial for children’s self-esteem and good behaviors, particularly in the American culture (Chao, 1995). Thus, to adapt and adjust to the values and practices of a new cultural environment, immigrant parents, such as Chinese immigrant mothers, may attempt to express more praise in interactions with their children (Sam & Berry, 2010).

Nevertheless, the role of praise in shy Chinese American children’s development is not well understood. Additionally, even though observational methodology has advantages over self-report approaches, few studies have observationally examined the use of praise in Chinese American families (Seo et al., 2017; Wang, Wiley, & Chiu, 2008). In the present study, the moderating role of Chinese immigrant mothers observed use of praise during a parent-child play session was examined in the associations of children’s temperamental shyness and their assertive and submissive responses to peer victimization through their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior.

Summary of the Current Study

When identifying the mechanisms underlying the relation between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their responses to peer victimization, the role of maternal praise may have important implications for helping parents positively influence shy children’s social interactions when they are confronted with peer victimization. Accordingly, the first aim of this study was to examine the relations between Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness and their responses to peer victimization and whether this association is mediated by children’s display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. We expected that children who are more temperamentally shy would exhibit higher levels of anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn would be linked to less assertiveness and more submissiveness in response to peer victimization. Furthermore, we explored whether Chinese immigrant mothers’ observed use of praise moderated the positive associations between children’s temperamental shyness and anxious-withdrawn behavior. Maternal praise was expected to attenuate the positive associations between children’s temperamental shyness and their display of anxious-withdrawn behavior, and consequent associations with responses to peer victimization.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study consisted of 153 Chinese immigrant mothers (Mage = 37.30 years, SDage = 4.19 years) with their young children (46.4% boys; Mage = 4.40 years, SDage = 0.79 years; range = 3 to 5 years) living in the Maryland/Washington metropolitan area in the United States. Fifty-one children (33.33%) preferred to use English when communicating with their parents and ninety children (58.82%) preferred to use English when communicating with peers. One hundred and twenty-eight (83.66%) children were born in the United States. Regarding children’s minority status, 40% of the participants reported living in a neighborhood with less than 25% of individuals with Chinese or other Asian ethnic backgrounds. Mothers had resided in the United States for an average of 10.50 years (SD = 6.21 years) and were generally well-educated, with 88% having a college or graduate degree. Approximately 8% of the mothers preferred to speak English, with the rest preferring to speak Chinese during home visits for data collection.

Procedure

The participants were recruited from various locations including supermarkets, churches, public libraries, and language schools in the Maryland-Washington DC, region. Participating Chinese immigrant mothers were informed about the objectives of the study and signed informed consent forms ensuring information confidentiality before data collection. Home visits were conducted by trained bilingual research assistants to assess maternal praise via mother–child interactions during a 15-min free-play. The mothers and children were told that they were free to play with anything in a bag that was provided with a standardized set of toys and to engage with the child as they normally would. The interactions were video recorded by the research assistant who stayed beside the camera to adjust the angle of the camera and ensure that both mothers and children were facing the camera. The research assistant was trained to remain unobtrusive during this period. Although mothers and children were aware that they were being observed, the home environment was familiar and comfortable. Other family members were asked not to be present during the task. At the end of the task, mothers were asked to rate how natural the session was, and all mothers rated that the session was “quite” or “very natural”. Mothers and their children could speak either in Chinese or in English during the free-play task. Within one week after the home visits, mothers completed a questionnaire on children’s temperamental shyness and a research assistant called the children’s teachers to obtain their ratings of children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior and their assertive and submissive responses to peer victimization in the school setting. Mothers received $40 for their participation. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from The University of Maryland, Baltimore Country (Protocol # 204 Y16CC20229; Title: The Development and Well-being of Asian Families in the United States).

Measures

Temperamental shyness.

Children’s temperamental shyness was measured using the mothers’ report on the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001), which has been validated on Chinese samples (Rothbart et al., 2001). We focused on the shyness subscale containing ten items (e.g., “Gets embarrassed when strangers pay a lot of attention to her/him,” “Acts shy around new people”). Mothers indicated the extent to which each statement was true along a 7- point Likert-type scale (from 1= extremely untrue to 7 = extremely true). A mean score was created for the shyness subscale so that higher scores reflected greater levels of temperamental shyness. McDonald’s omega statistic was performed to examine the reliability of the scale. The Omega coefficient in this sample was .93.

Maternal praise.

Mothers’ observed engagement in praise was coded following the Parental Warmth and Control Scale developed by Rubin and Cheah (2014). We focused on the praise subscale in this coding scheme, which measures the frequency of mother’s positive evaluation of the child or child’s work during a free-play task (e.g., “You are smart!” “That’s a good idea!”). Specifically, each of the mother’s positive statements regarding the child’s attributes, working process or products or general praise which did not clearly target the object of the praise (e.g., “Good!”, “Great!”), was coded as a praise statement and counted as one instance of praise (Seo et al., 2017). The free-play session was coded in segments of ten seconds, where the frequency of maternal praise was provided for each ten-seconds observed by Mangold INTERACT behavioral observation coding software (Mangold, 2015). The frequencies of maternal praise were converted to proportions for data analyses to control for slight variations in the length of free-play segments. Specifically, the total number of times the mother praised the child was divided by the number of segments for each dyad. Coding was conducted by a team of trained Chinese bilingual coders. The reliability of the coding was assessed on a randomly selected sample of 20% of the total cases. Reliability between coders for the maternal praise scores was high (Cohen’s Kappa = .93). Disagreements were resolved by consensus between coders.

Anxious-Withdrawn Behavior.

Children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior was assessed using teacher-reports on the Teacher Behavior Rating Scale (TBRS; Hart & Robinson, 1996), specifically, the withdrawn subscale, which consists of six items (e.g., “Is fearful in approaching other children,” “Is quiet around other children” “Shies away when approached by other children”) and has been validated on preschool-age Chinese American children (Balkaya et al., 2018). Teachers were instructed to rate the frequency of children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior on a 3-point Likert Scale (0 = never, 1= sometimes, 2 = very often). Mean scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating more teacher-reported display of anxious-withdrawn behavior. We also conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to further examine the psychometric properties of this instrument. Results of the CFA indicated that the one-factor model with six items showed a good fit with the data, χ2 (9) = 14.37, p = .11, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .03, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, with all items having factor loadings higher than the recommended minimum of 0.40 in the current sample with a range between 0.58 and 0.79, p < .001. The Omega coefficient was .86 in the current sample.

Responses to peer victimization.

Children’s responses to peer victimization were also reported by their teachers on response to peer victimization subscale of the TBRS. Six items from this scale were used to measure children’s assertive responses to peer victimization (e.g., “Tells child who tries to intimidate him/her that he/she ‘doesn’t like it,’ or something to that effect,” “Tells child who tries to be mean to ‘stop it right now’ or something to that effect,” “Stands up assertively but not aggressively to bullies,” “Says assertively, but without hostility, something like “that’s mine” or “give it back” in a firm voice when another child takes something of his/hers,” “Tells bully to ‘go bother somebody else’ or something to that effect”); and four items of this scale were designed to assess submissive responses to aggression (e.g., “Cowers when confronted aggressively by peers,” “Cries when picked on by peers,” “Cowers or slinks away when confronted by a bully,” “Withdraws when provoked by peers”). The response range varies from 0 = never to 2 = very often. Mean scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating more assertiveness or submissiveness in response to peer victimization. These two subscales have been shown to have good factor validity (e.g., factor loadings in the high .60s to the mid .80s for each scale) and good scale reliability Cronbach’s alphas .83 and .88 in a sample of primarily European American children (Hart & Robinson, 1996). However, to our knowledge it has never been used with Chinese American children. The results of the CFA indicated that the model fit of two-factor model was acceptable, χ2 2(26) = 52.39, p < .05, RMSEA =.08, SRMR = .08, CFI =.90, TLI = 0.87, with all items having factor loadings higher than the recommended minimum of 0.40 in the current sample with a range between 0.43 and 0.72, p < .001. The Omega coefficient for the assertiveness scale was .74 and for the submissiveness scale was .74 in the present sample.

Data Analytic Plan

Observed Variable Path Analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) using the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation method. The MLR estimator was selected because it provides standard errors and chi-square test statistic that are robust to non-normal data and it works well with small and medium sample sizes (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2002). Furthermore, chi-squared statistic (χ2), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were examined to assess the model fit. RMSEA < .06, SRMR < .08, CFI > .95, and TLI > .95 indicates a good fit of hypothesized model (Hu & Bentler, 1998). The interaction term was created by multiplying temperamental shyness by maternal praise. In case of a significant interaction, simple slope tests were conducted to calculate the simple effects of temperamental shyness on anxious-withdrawn behavior at low (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), mean, and high levels (i.e., 1 SD above the mean) of maternal praise. Finally, bias-corrected bootstrap tests with 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples were used to examine conditional indirect effects of temperamental shyness on the study outcomes. Conditional indirect effects can be deemed to be significant when 95% CI does not include 0 (Hayes, 2013). Previous research has linked child age and gender with children’s social adjustment. Thus, these variables were included as potential covariates in the proposed model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables are reported in Table 1. Children’s shyness was positively associated with their anxious-withdrawn behavior. Moreover, children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior was negatively related with their assertive responses to peer victimization and positively correlated with their submissive responses to peer victimization. These correlations indicated that children who were more temperamentally shy were more likely to behave in anxious-withdrawn ways in the presence of their peers. Moreover, children who displayed more anxious-withdrawn behaviors were more likely to respond in submissive ways to aggressive provocations, and children who were less anxious-withdrawn were more likely to be assertive when faced with peer victimization. Shyness was significantly related to submissiveness but not to assertiveness. However, as suggested by Zhao, Lynch, and Chen (2010), the significance of the indirect effect is the only requirement for mediation. Thus, it is not necessary for shyness to be significantly associated with assertiveness for mediation to be present. Correlations between covariates (i.e., child age and gender) and study outcomes variables (i.e., anxious-withdrawn behavior, assertiveness, and submissiveness) were not significant. Therefore, these covariates were not included in the final moderated mediation model to avoid overcontrol (Little, 2013).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of main study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | range | skewness | kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shyness | -- | 3.07 | .16 | [1.10, 6.80] | .13 | −.69 | |||||

| 2. Maternal Praise | −.03 | -- | 0.78 | 0.06 | [.00, .11] | 2.66 | 8.70 | ||||

| 3. Anxious Withdrawal | .34*** | −.11* | -- | 1.12 | 0.07 | [.00, 2.00] | 1.05 | .79 | |||

| 4. Assertiveness | −.07 | .05 | −.29*** | -- | 1.78 | 0.12 | [.00, 2.00] | .24 | −.25 | ||

| 5. Submissiveness | .16* | −.16* | .57*** | −.03 | -- | 0.99 | 0.07 | [.00, 1.75] | .95 | .25 | |

| 6. Child Gender | −.02 | −.05 | −.07 | .11 | .05 | -- | 1.52 | 0.04 | [1.00, 2.00] | −.10 | −2.02 |

| 7. Child Age | .01 | .03 | .07 | −.02 | −.16 | .03 | 4.40 | 0.79 | [3.00, 5.97] | −.12 | −.89 |

Note. N = 153. Child Gender was coded (1 = male; 2 = female).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Path Analyses

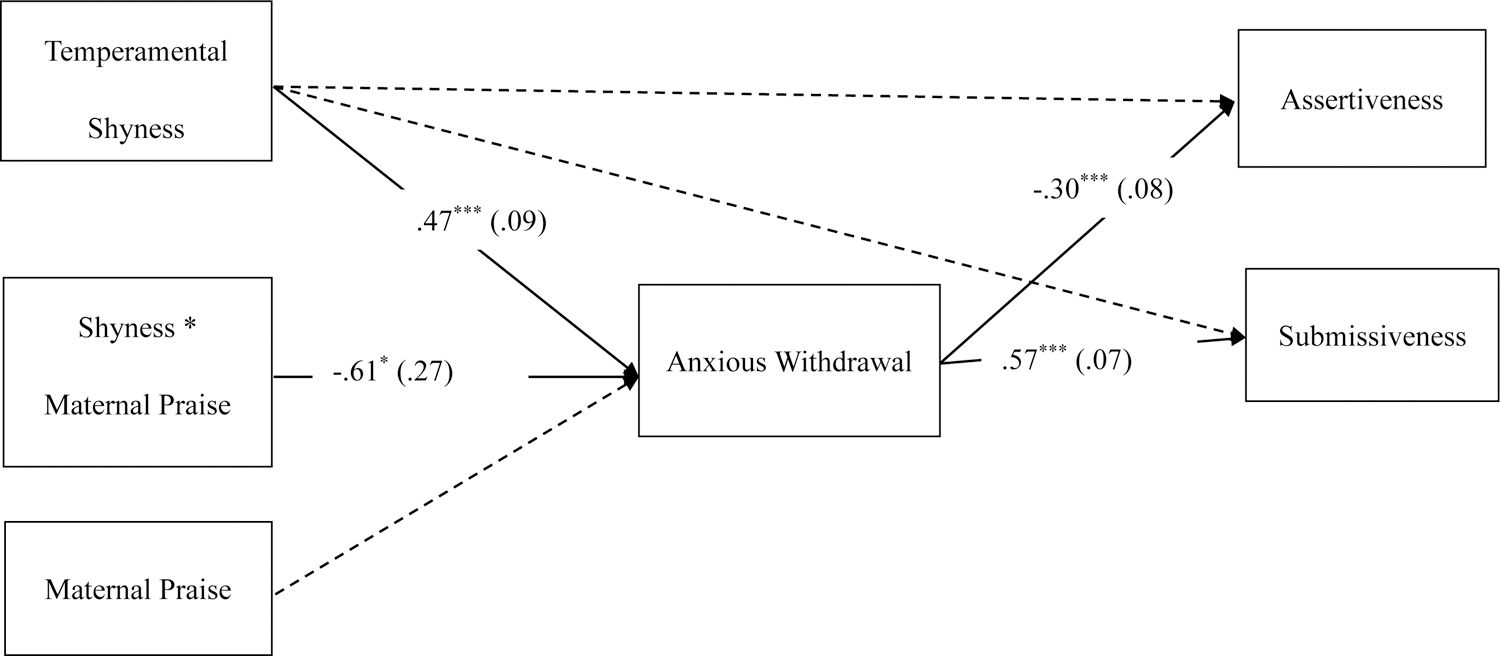

The overall model (see Figure 1) achieved good fit, χ2 (5, N = 153) = 3.09, p = .69, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.05, SRMR = .03, and RMSEA = .00, 90% CI [.00, .09]. For children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior (σ2 = .18), there was a significant positive main effect of temperamental shyness (b = 0.18, SE = 0.04, p < .001), but the main effect of maternal praise on anxious-withdrawn behavior was not significant (b = 12.32, SE = 6.48, p = .06). More importantly, there was a significant interaction effect between child shyness and maternal praise on anxious-withdrawn behavior (b = −4.13, SE = 1.77, p = .03). In turn, children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior was positively associated (b = 0.53, SE = 0.07, p < .001) with their submissiveness in response to peer victimization (σ2 = .13) and negatively associated (b = −0.30, SE = 0.08, p < .001) with their assertiveness in response to peer victimization (σ2 = .19).

Figure 1.

The final moderated mediation model. Significant standardized coefficients [β(SE)] were indicated in the figure and unstandardized coefficients were presented in the text. Solid lines represent significant paths and dashed lines represent non-significant paths. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

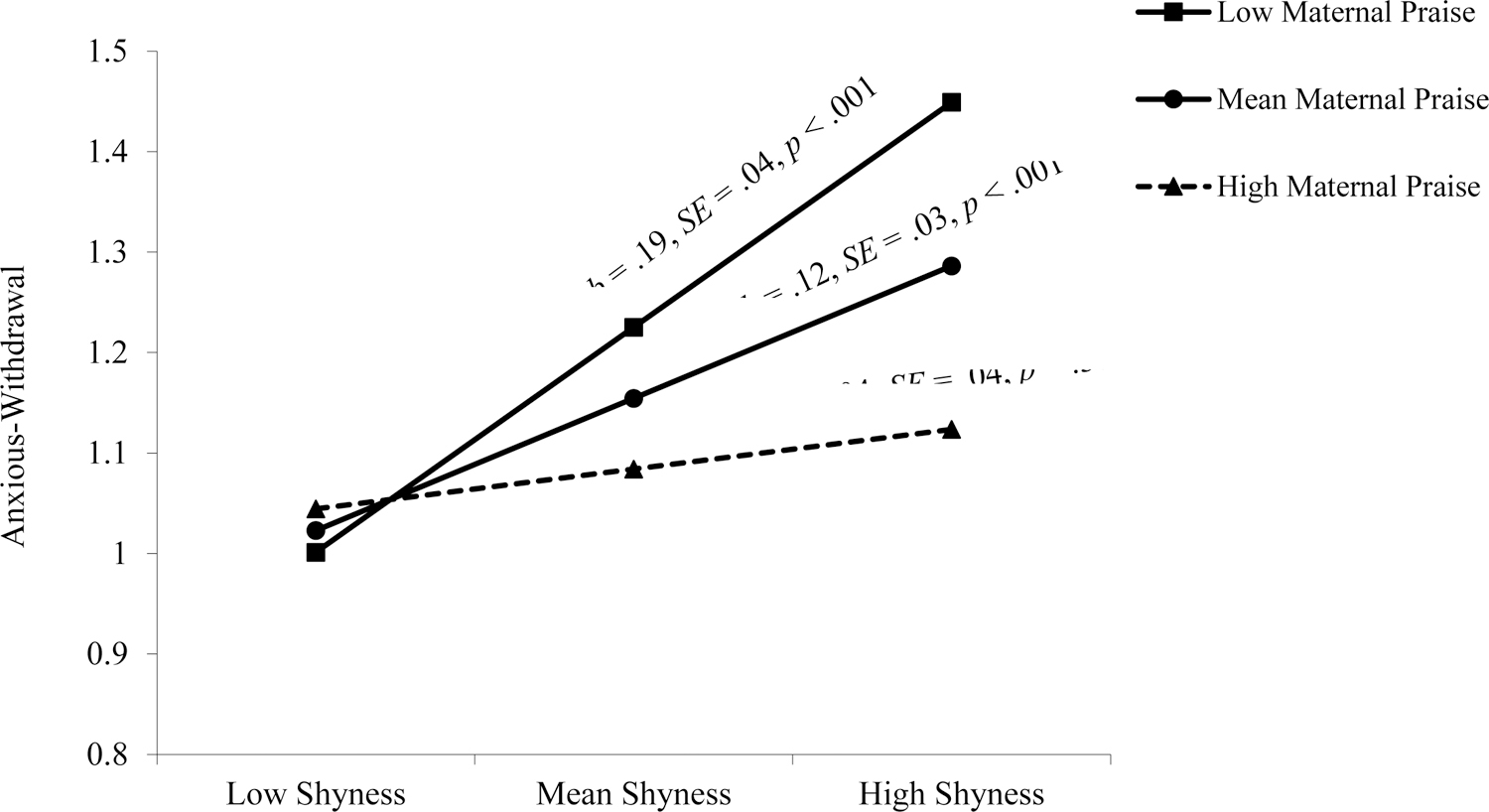

To probe the interaction effect between child shyness and maternal praise on anxious-withdrawn behavior, simple slopes analyses were performed to examine the effect of shyness on anxious-withdrawn behavior at low, mean, and high levels of maternal praise (Figure 2). Whereas child shyness was positively related to anxious-withdrawn behavior at low (b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, p < .001) and mean (b = 0.12, SE = 0.03, p < .001) levels of maternal praise, this association was no longer significant at high levels of maternal praise (b = 0.04, SE = 0.04, p = .37). In other words, increasing levels of maternal praise attenuated the positive relation between child shyness and anxious-withdrawn behavior.

Figure 2.

Maternal praise moderated the relation between temperamental shyness and anxious-withdrawn behavior.

To test the significance of the conditional indirect effects, the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval approach was used to examine the indirect effects of child temperamental shyness on their responses to peer victimization through their anxious-withdrawn behavior at different levels of maternal praise. We found that the indirect effect of child shyness on their assertiveness in response to peer victimization through anxious-withdrawn behavior was negative and significant at low (b = −0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.10, −0.02]) and mean levels (b = −0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.01]) of maternal praise. In contrast, at high levels of maternal praise (b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.11]), the negative indirect effect of child shyness on their assertiveness in response to peer victimization through anxious-withdrawn behavior was not significant. These findings indicated that the negative indirect relations between child shyness and their assertiveness in response to peer victimization through their anxious-withdrawn behavior were attenuated with increasing levels of their mothers’ praise.

Similarly, at low (b = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.06, 0.15]) and mean levels (b = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.03, 0.10]) of maternal praise, the indirect effect of child shyness on their submissive responses to peer victimization through anxious-withdrawn behavior was positive and significant. In contrast, at high levels of maternal praise (b = 0.02, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.08]), the indirect effect of child shyness on their submissive responses through anxious-withdrawn behavior was not significant. These results suggested that the indirect relations between child shyness and their submissiveness in response to peer victimization through their anxious-withdrawn behavior were attenuated with increasing levels of their mothers’ praise.

Finally, after controlling for the effects of anxious-withdrawn behavior, the direct effects of shyness on assertiveness (b = −0.003, SE = 0.02, p = .88) and submissiveness (b = −0.003, SE = 0.02, p = .88) were not significant, indicating that temperamental shyness was only associated with children’s assertive and submissive responses to peer victimization through their anxious-withdrawn behavior.

Discussion

Little is known about how shy children respond to peer victimization, especially Chinese American children in early childhood. The current study examined the relations between preschool-aged Chinese American children’s shyness and their assertive and submissive responses to peer victimization through the mediating role of their anxious-withdrawn behavior. Additionally, we used an observational measure of maternal praise, which provides more objective assessment of this parenting behavior, to investigate whether the role of maternal praise served as a potential buffer to deflect children’s temperamental shyness.

Previous research indicated that preschool children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior mediated the links between temperament shyness and social adjustment including prosocial behavior, peer exclusion and assertiveness skills (Balkaya et al., 2018); our study extended these findings to reveal that temperamental shyness in Chinese American children is not only associated with their greater display of anxious-withdrawn behavior with peers, but is in turn related to fewer assertive responses and more avoidant responses in specific peer victimization contexts. A growing body of research has found that ineffective coping strategies, such as submissiveness, increase the frequency of being victimized (e.g., Perren & Alsaker, 2006). In contrast, assertive reactions to peer victimization have been shown to be effective coping strategies in response to peer victimization because they decrease the likelihood of future peer victimization (Boket, Bahrami, Kolyaie, & Hosseini, 2016). Previous studies found that children who are more temperamentally shy are less assertive in their interactions with peers and tend to be avoidant when they are confronted with stressful social situations (Colonnesi et al., 2014). In addition, withdrawn children have been found to endorse submissive coping strategies (Stewart & Rubin, 1995), and tend to endorse nonassertive strategies such as internalizing emotional reactions (Burgess, Wojslawowicz, Rubin, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth-LaForce, 2006). The results of the present study further contributed to these findings by suggesting that children’s engagement in anxious-withdrawn behavior emerged as a mediator in the relation between children’s temperamental shyness and their assertive and submissive responses to bullying, which may have important implications for recognizing temperamental shyness as a risk factor for more maladaptive responses to peer victimization.

Although shyness is biologically rooted, findings from a variety of studies have shown that the behavioral display of shyness can be modulated by parenting practices in early childhood. For example, Grady and Hastings (2018) evaluated the moderating role of parental emotion language on the associations between 2- to 5-year-old children’s temperamental shyness and their prosocial behavior, revealing that when parents use more elaborative emotion language, their shy children demonstrated more active prosocial behaviors. In line with the previous studies on the moderating effects of positive parenting practices, our study revealed that mothers’ use of praise during parent-child interactions may mitigate the interpersonal risk of children’s temperamental shyness by attenuating their tendencies to engage in anxious-withdrawn behavior with peers, which ultimately put them at risk for being bullied in American school contexts where assertiveness is highly appraised and withdrawn behavior is considered socially immature (Rubin et al., 2009).

Importantly, of particular interest to this study was a culturally less-emphasized parenting practice for Chinese parents, specifically maternal praise. Despite the cultural tendency to downplay the use of maternal praise, the results indicated that maternal praise alleviated the effects of temperamental shyness on the display of anxious-withdrawn behavior in Chinese American children. In other words, the more frequently Chinese immigrant mothers praised their children, the less likely their temperamentally shy children were to engage in anxious-withdrawn behavior, which in turn was related to more effective coping strategies in response to peer victimization. One possibility that might account for the current pattern of findings is that mothers’ praise might be beneficial for enhancing children’s social skills resulting in more fulfilling peer group interactions, which makes them less likely to withdraw from their peers and ultimately increases their engagement in assertive responses as well as decreases their tendencies to use submissive response in the face of peer victimization. This conjecture is supported by Shinohara and colleagues’ (2012) longitudinal studies demonstrating that when children received continuous positive feedback and evaluations from their mothers, they demonstrated a decreased risk for poor social competence.

Another possible explanation for this finding is that maternal praise is related to young children’s self-evaluations as expressed in their self-evaluative affect such as pride and shame. Mothers’ praise may promote children’s self-esteem (Kelley, Brownell, & Campbell, 2000), which may promote shy children’s self-assurance when interacting with their peers. Hence, maternal praise might encourage shy children to not withdraw themselves from peer group interactions in an anxious manner and to be more assertive and less submissive in responses to peer victimization. Of note, since parental praise is a component of positive parenting which is highly negatively related to negative parenting, it is plausible that the potential covarying effects of negative parenting may influence the findings. Thus, further studies could examine parental praise and negative parenting components such as criticism and over-control together to clarify the unique functions of praise.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the current study was a cross-sectional study design. Therefore, the results are considered exploratory and do not allow for the establishment of causal inferences and conclusions regarding the temporality of these effects (Selig & Preacher, 2009). However, the conceptual model in the present study is based on aforementioned theoretical perspectives (e.g., Coplan et al., 2008) and empirical studies (e.g., Balkaya et al., 2018; Van Zalk & Kerr, 2011) on the effects of parenting practices on the behavioral display of shyness. In accordance with Shrout (2011)’s statement that cross-sectional mediation analyses can be informative about causal processes under the well-established theories, our findings provide preliminary evidence of the need for further exploration of the related temporal process. Further studies can use longitudinal designs to make inferences about the temporal relations between children’s temperamental shyness, anxious-withdrawn behavior and their responses to peer victimization.

Another limitation of the present study is that we used the same informant (i.e., teacher) to assess children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior and responses to peer victimization which may lead to an overestimation of the associations among the constructs (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Although we used maternal reports of temperament shyness and observations of maternal praise, future studies should include additional informants of children’s behavioral responses, such as peers, to enhance confidence in the conclusions.

Last, although prior studies indicate that that Asian American youth are at greater risk of peer victimization relative to non-Asian American peers (e.g., Hong et al., 2014), we did not assess the frequency of children’s exposure to peer victimization in the current sample. As noted earlier, prior research suggests that most children in early childhood settings experience frequent peer victimization and their teachers who complete behavioral assessments are more likely tuned into their social experiences relative to teachers in school settings with older children. However, this needs to be more conclusively verified in future research. Also, little is known about how much coaching anxious-withdrawn children might receive from teachers in responding to peer victimization which may depend, in part, on the supportive nature of the teacher, the teacher-child relationship, and help-seeking behavior which may be less likely to occur for younger, socially withdrawn children. This is an area ripe for future empirical inquiry in early childhood settings (e.g., Runions & Shaw, 2013). Further studies should also measure the experience of peer victimization with child self-reports and observational methods as well as ascertain the prevalence of peer victimization utilizing teacher reports to further support the validity of teachers’ ratings as well as the generalization of the results of this study.

Conclusions and Implications

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, our study is among the first to demonstrate that temperamental shyness in Chinese American children may present a risk for children’s use of less effective strategies in response to peer victimization. Moreover, the potential mediating pathway through which Chinese American children’s temperamental shyness is linked to their responses to peer victimization indicates that shy children’s anxious-withdrawn behavior rather than their temperamental disposition, is associated with an increased risk of using submissive responses to peer victimization.

Although a substantial body of research has established the influence of parenting on shy children’s social outcomes (e.g., Grady & Karraker, 2014), relatively little research has examined the effect of the specific aspects of parenting, especially maternal praise, on the link between temperamental shyness in Chinese American children and their responses to peer victimization. Based on previous early intervention programs aimed at assisting preschool-aged children with shyness and anxiety through fostering positive parenting practices (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2017), our results extend the evidence that the use of praise can help children reduce their social fear and anxiety. These findings suggest a potentially effective avenue for implementing prevention and intervention programs tailored towards parents to reduce their shy children’s interpersonal difficulties with peers.

Finally, the present study examined ways to modify temperamentally shy children’s social behavior at a young age when most children are developing interaction patterns with unfamiliar peers. Previous studies have revealed that shy children interact less with others than do their peers, which increases the risk of social withdrawal in later development without early intervention (e.g., Grady & Karraker, 2014). The findings from this study with preschool-aged children can inform the development of early parenting interventions designed for Chinese immigrant mothers to express appropriate praise when interacting with their children, which may decrease the display of anxious-withdrawn behavior in temperamentally shy children and facilitate their development of adaptive social skills for dealing with incidences of peer victimization.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the Foundation for Child Development and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R03HD052827–01) awarded to Charissa S. L. Cheah, and a Marjorie Pay Hinckley Endowed Chair seed money grant and the Zina Young Williams Card Professorship at Brigham Young University awarded to Craig H. Hart. We would like to thank the parents and children who participated in our study.

Contributor Information

Dan Gao, School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University

Craig H. Hart, School of Family Life, Brigham Young University

Charissa S. L. Cheah, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Merve Balkaya, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Kathy T. T. Vu, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Junsheng Liu, School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University

References

- Acar IH, Rudasill KM, Molfese V, Torquati J, & Prokasky A (2015). Temperament and preschool children’s peer interactions. Early Education and Development, 26, 479–495. 10.1080/10409289.2015.1000718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaker FD, & Valkanover S (2002). Early diagnosis and prevention of victimization in kindergarten. In Juvonen J, & Graham S (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: the plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 175–95). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balkaya M, Cheah CSL, Yu J, Hart CH, & Sun S (2018). Maternal encouragement of modest behavior, temperamental shyness, and anxious withdrawal linkages to Chinese American children’s social adjustment: A moderated mediation analysis. Social Development, 27, 876–890. 10.1111/sode.12295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely-McClure SJ, & Ostrov JM (2018). Examining co-occurring and pure relational and physical victimization in early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 1–16. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boket EG, Bahrami M, Kolyaie L, & Hosseini SA (2016). The effect of assertiveness skills training on reduction of verbal victimization of high school students. International Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies, 3, 2356–5926. 10.3126/ijls.v9i4.12679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Wojslawowicz JC, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, & Booth-LaForce C (2006). Social information processing and coping strategies of shy/withdrawn and aggressive children: Does friendship matter? Child development, 77, 371–383. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00876.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas JF, & Bower AA (2018). Developmental manifestations of relational aggression. In Coyne SM & Ostrov JM (Eds.), The development of relational aggression (pp. 29–48). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK (1995). Chinese and European American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers’ childrearing beliefs. Ethos, 23, 328–354. 10.1525/eth.1995.23.3.02a00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Li J, Zhou N, Yamamoto Y, & Leung CYY (2015). Understanding Chinese immigrant and European American mothers’ expressions of warmth. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1802–1811. 10.1037/a0039855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Chen H (2012). Children’s social functioning and adjustment in the changing Chinese society. In Silbereisen RK and Chen X (Eds.), Social change and human development: Concepts and results. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, O’Brien Kelly A., Coplan RJ, Thomas SR, & Dougherty LR, …Wimsatt M (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a multimodal early intervention program for behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 534–540. 10.1037/a0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnesi C, Napoleone E, & Bögels SM (2014). Positive and negative expressions of shyness in toddlers: Are they related to anxiety in the same way? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 624–637. 10.1037/a0035561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Vaillancourt T, LeBlanc JC, Nagin DS, & Tremblay RE (2006). The development of physical aggression from toddlerhood to pre-adolescence: A nationwide longitudinal study of Canadian children. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 34, 68–82. 10.1007/s10802-005-9001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Grotpeter JK (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child development, 66, 710–722. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Appleyard K, Jansen EA, & Casas JF (2004). Relational Aggression in Early Childhood: “You Can’t Come to My Birthday Party Unless…” In Putallaz M & Bierman KL (Eds.), Duke series in child development and public policy. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls: A developmental perspective (p. 71–89). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Burr JE, Cullerton-Sen C, Jansen-Yeh E, & Ralston P (2006). A longitudinal study of relational and physical aggression in preschool. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27, 254–268. 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiBiase R, & Miller PM (2015). Self-perceived peer acceptance in preschoolers of differing economic and cultural backgrounds. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 176, 139–155. 10.1080/00221325.2015.1022504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, & Eisenberg N (1992). Young children’s coping with interpersonal anger. Child Development, 63, 116–128. 10.2307/1130906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godleski SA, Kamper KE, Ostrov JM, Hart EJ, & Blakely-McClure SJ (2015). Peer victimization and peer rejection during early childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 380–392. 10.1080/15374416.2014.940622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady JS, & Hastings PD (2018). Becoming prosocial peers: The roles of temperamental shyness and mothers’ and fathers’ elaborative emotion language. Social Development, 27, 858–875. 10.1111/sode.12300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grady JS, & Karraker K (2014). Do maternal warm and encouraging statements reduce shy toddlers’ social reticence? Infant & Child Development, 23, 295–303. 10.1002/icd.1850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, Newell LD, & Olsen SF (2003). Parenting skills and social-communicative competence in childhood. In Greene JO & Burleson BR (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. (pp. 753–797). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, & Robinson CC (1996). Teacher Behavior Rating Scale. Unpublished teacher questionnaire. Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderlong J, & Lepper MR (2002). The effects of praise on children’s intrinsic motivation: A review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 774–795. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L, & Zimbardo PG (1998). Shyness. In Friedman HS, Schwartzer R, Cohen Silver R, & Spiegel D (Eds.), Encyclopedia of mental health (Vol. 3, pp. 497–509). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Peguero AA, Choi S, Lanesskog D, Espelage DL, & Lee NY (2014). Social ecology of bullying and peer victimization of Latino and Asian youth in the United States: A review of the literature. Journal of School Violence, 13, 315–338. 10.1080/15388220.2013.856013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GH, & Gove M (2012). Confucianism and Chinese families: Values and practices in education. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kamper-DeMarco KE, & Ostrov JM (2017). Prospective associations between peer victimization and social-psychological adjustment problems in early childhood. Aggressive behavior, 43(5), 471–482. 10.1002/ab.21705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SA, Brownell CA, & Campbell SB (2000). Mastery motivation and self-evaluative affect in toddlers: Longitudinal relations with maternal behavior. Child Development, 71, 1061–1071. 10.1111/1467-8624.00209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, & Hong S (2007). First-generation Korean-American parents’ perceptions of discipline. Journal of Professional Nursing, 23, 60–68. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B (2004). Peer victimization: The role of emotions in adaptive and maladaptive coping. Social Development, 13, 329–349. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00271.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, & Ladd GW (1996). Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of children’s school adjustment difficulties. Child Development, 67,1293–1305. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, & Ladd GW (1997). Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and psychopathology, 9, 59–73. 10.1017/S0954579497001065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygsman A, & Vaillancourt T (2019). Peer victimization, aggression, and depression symptoms in preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 62–73. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau EX, Rapee RM, & Coplan RJ (2017). Combining child social skills training with a parent early intervention program for inhibited preschool children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 51, 32–38. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Bowker JC, Coplan RJ, Yang P, Li D, & Chen X (2019). Evaluating links among shyness, peer relations, and internalizing problems in Chinese young adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29, 696–709. 10.1111/jora.12406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Mangold (2015). INTERACT 14 User Guide. Mangold International GmbH; (Ed.) www.mangold-international.com [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly-Choque MK, Hart CH, Robinson CC, Nelson LJ, & Olsen SF (1996). Overt and relational aggression on the playground: Correspondence among different informants. Journal of research in childhood education, 11, 47–67. 10.1080/02568549609594695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monks C, Ortega Ruiz R, & Torrado Val E (2002). Unjustified aggression in preschool. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 458–476. 10.1002/ab.10032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CP, & Smith PK (2006). Definitions of bullying: Age differences in understanding of the term, and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24, 801–821. 10.1348/026151005X82352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CP, Smith PK, & Swettenham J (2005). Psychological correlates of peer victimization in preschool: social cognitive skills, executive function and attachment profiles. Aggressive Behavior, 31, 571–588. 10.1002/ab.20099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, & Asparouhov T (2002). Latent Variable Analysis With Categorical Outcomes: Multiple-Group And Growth Modeling In Mplus. Online.

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Eighth Ed.). Los Angeles (CA): Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Hart CH, Evans CA, Coplan RJ, Roper SO, & Robinson CC (2009). Behavioral and relational correlates of low self-perceived competence in young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 350–361. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D (1993). Bullies on the playground: The role of victimization. In Hart CH (Ed.), Children on playgrounds: Research perspectives and applications (pp. 85–128). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Kamper KE, Hart EJ, Godleski SA, & Blakely-McClure SJ (2014). A gender-balanced approach to the study of peer victimization and aggression subtypes in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 575–587. 10.1017/S0954579414000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Kamper-DeMarco KE, Blakely-McClure SJ, Perry KJ, & Mutignani L (2019). Prospective associations between aggression/bullying and adjustment in preschool: Is general aggression different from bullying behavior? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2572–2585. 10.1007/s10826-018-1055-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, & Alsaker FD (2006). Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 47, 45–57. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry KJ, Meisel SN, Stotsky MT, & Ostrov JM (2020). Parsing apart affective dimensions of withdrawal: Longitudinal relations with peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 1–13. 10.1017/S0954579420000346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, & Podsakoff NP (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, & Coplan RJ (2010). Conceptual relations between anxiety disorder and fearful temperament. In Gazelle H & Rubin KH (Eds.), Social anxiety in childhood: Bridging developmental and clinical perspectives. (Vol. 2010, pp. 17–31). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reunamo J, Kalliomaa M, Repo L, Salminen E, Lee HC, & Wang LC (2015). Children’s strategies in addressing bullying situations in day care and preschool. Early Child Development and Care, 185, 952–967. 10.1080/03004430.2014.973871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, & Fisher P (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394. 10.1111/1467-8624.00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, & Hastings PD (2002). Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development, 73, 483–495. 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Cheah CSL (2014). Parental Warmth and Control Scale Revised (Unpublished). College Park, MD: University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, & Bowker JC (2009). Social Withdrawal in Childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runions KC, & Shaw T (2013). Teacher-child relationship, child withdrawal and aggression in the development of peer victimization. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34, 319–327. 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salili F (1996). Learning and motivation: An Asian perspective. Psychology and Developing Societies, 8, 55–81. 10.1177/097133369600800104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, & Berry JW (2010). Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 472–481. 10.1177/1745691610373075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, & Preacher KJ (2009). Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Research in Human Development, 6, 144–164. 10.1080/15427600902911247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo YJ, Cheah CSL, & Hart CH (2017). Korean immigrant mothers’ praise and encouragement, acculturation, and their children’s socioemotional and behavioral difficulties. Parenting: Science and Practice, 17, 143–155. 10.1080/15295192.2017.1304786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara R, Sugisawa Y, Tong L, Tanaka E, Watanabe T, Kawashima Y, … & Amarsanaa GY (2012). Influence of maternal praise on developmental trajectories of early childhood social competence. Creative Education, 3, 533. 10.4236/ce.2012.34081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE (2011). Commentary: Mediation analysis, causal process, and cross-sectional data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 852–860. 10.1080/00273171.2011.606718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, & Rubin KH (1995). The social problem-solving skills of anxious-withdrawn children. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 323–336. 10.1017/S0954579400006532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YZ, Wiley AR, & Chiu C-Y (2008). Independence-supportive praise versus interdependence-promoting praise. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32, 13–20. 10.1177/0165025407084047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zalk N, & Kerr M (2011). Shy adolescents’ perceptions of parents’ psychological control and emotional warmth: Examining bidirectional links. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57, 375–401. 10.1353/mpq.2011.0021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou M, Botsoglou K, & Andreou E (2013). Assessing bully/victim problems in preschool children: A multimethod approach. Journal of Criminology, 2013, 1–8. 10.1155/2013/301658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Cheah CSL, Hart CH, Yang C, & Olsen JA (2019). Longitudinal effects of maternal love withdrawal and guilt induction on Chinese American preschoolers’ bullying aggressive behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 1467–1475. 10.1017/S0954579418001049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG Jr, & Chen Q (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. 10.1086/651257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]