ABSTRACT

Background: About 40% of rape victims develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within three months after the assault. Considering the high personal and societal impact of PTSD, there is an urgent need for early (i.e. within three months after the incident) interventions to reduce post-traumatic stress in victims of rape.

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of early intervention with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress, feelings of guilt and shame, sexual dysfunction, and other psychological dysfunction (i.e. general psychopathology, anxiety, depression, and dissociative symptoms) in victims of rape.

Method: This randomized controlled trial included 57 victims of rape, who were randomly allocated to either two sessions of EMDR therapy or treatment as usual (‘watchful waiting’) between 14 and 28 days post-rape. Psychological symptoms were assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 8 and 12 weeks post-rape. Linear mixed models and ANCOVAs were used to analyse differences between conditions over time.

Results: Within-group effect sizes of the EMDR condition (d = 0.89 to 1.57) and control condition (d = 0.79 to 1.54) were large, indicating that both conditions were effective. However, EMDR therapy was not found to be more effective than watchful waiting in reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms, general psychopathology, depression, sexual dysfunction, and feelings of guilt and shame. Although EMDR therapy was found to be more effective than watchful waiting in reducing anxiety and dissociative symptoms in the post-treatment assessment, this effect disappeared over time.

Conclusions: The findings do not support the notion that early intervention with EMDR therapy in victims of rape is more effective than watchful waiting for the reduction of psychological symptoms, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Further research on the effectiveness of early interventions, including watchful waiting, for this specific target group is needed.

KEYWORDS: EMDR therapy, early intervention, rape, sexual assault, PTSD

HIGHLIGHTS

Two sessions of EMDR therapy between two and four weeks post-rape were no more effective than treatment as usual in reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress and other psychopathology.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: Aproximadamente el 40% de las víctimas de violación desarrollan trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) dentro de los tres meses posteriores a la agresión. Teniendo en cuenta el alto impacto personal y social del TEPT, existe una necesidad urgente de intervenciones tempranas (es decir, dentro de los tres meses posteriores al incidente) para reducir el estrés postraumático en las víctimas de violación.

Objetivo: Evaluar la efectividad de la intervención temprana con terapia de desensibilización y reprocesamiento por movimiento ocular (EMDR en su sigla en inglés) para reducir los síntomas de estrés postraumático, sentimientos de culpa y vergüenza, disfunción sexual, y otras disfunciones psicológicas (es decir, psicopatología general, ansiedad, depresión, y síntomas disociativos) en víctimas de violación.

Método: Este ensayo controlado aleatorizado incluyó a 57 víctimas de violación, que fueron asignadas al azar a dos sesiones de terapia EMDR o al tratamiento habitual (“espera vigilante”) entre 14 y 28 días después de la violación. Los síntomas psicológicos se evaluaron antes del tratamiento, después del tratamiento, y 8 y 12 semanas después de la violación. Se utilizaron modelos lineales mixtos y ANCOVAs para analizar las diferencias entre las condiciones a lo largo del tiempo.

Resultados: Los tamaños del efecto dentro del grupo de la condición EMDR (d = 0.89 a 1.57) y la condición de control (d = 0.79 a 1.54) fueron grandes, lo que indica que ambas condiciones fueron efectivas. Sin embargo, no se encontró que la terapia EMDR fuera más efectiva que la espera vigilante para reducir los síntomas de estrés postraumático, la psicopatología general, la depresión, la disfunción sexual, y los sentimientos de culpa y vergüenza. Aunque se encontró que la terapia EMDR era más efectiva que la espera vigilante para reducir la ansiedad y los síntomas disociativos en la evaluación posterior al tratamiento, este efecto desapareció con el tiempo.

Conclusiones: Los hallazgos no apoyan la noción de que la intervención temprana con terapia EMDR en víctimas de violación sea más efectiva que la espera vigilante para la reducción de los síntomas psicológicos, incluyendo los síntomas del estrés postraumático. Se necesitan más investigaciones sobre la efectividad de las intervenciones tempranas, incluida la espera vigilante, para este grupo objetivo específico.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Terapia EMDR, intervención temprana, violación, agresión sexual, TEPT

Short abstract

背景: 大约 40% 的强奸受害者在遭受袭击后的三个月内发展出创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD)。考虑到 PTSD 对个人和社会的巨大影响, 迫切需要早期 (即在事件发生后三个月内) 干预以减轻强奸受害者的创伤后应激。

目的: 评估眼动脱敏和再加工 (EMDR) 疗法的早期干预减轻强奸受害者的创伤后应激症状, 内疚和羞耻感, 性功能障碍和其他心理功能障碍 (即一般精神病, 焦虑, 抑郁和解离症状) 的有效性。

方法: 本随机对照试验包纳入了57 名强奸受害者, 他们在被强奸后 14 至 28 天之间被随机分配到两个疗程的 EMDR 疗法或常规治疗 (‘观察等待’) 。在治疗前, 治疗后以及强奸后 8 和 12 周评估心理症状。线性混合模型和 ANCOVA 用于分析条件之间随时间的差异。

结果: EMDR 条件 (d = 0.89 至 1.57) 和对照条件 (d = 0.79 至 1.54) 的组内效应量较大, 表明两种条件均有效。然而, 在减少创伤后应激症状, 一般精神病, 抑郁, 性功能障碍以及内疚和羞耻感方面, 没有发现 EMDR 疗法比观察等待更有效。尽管在治疗后评估中发现在减轻焦虑和解离症状上, EMDR疗法比观察等待更有效, 但此效应会随时间的推移而消失。

结论: 研究结果不支持EMDR 疗法的早期干预比观察等待在减轻强奸受害者的心理症状, 包括创伤后应激症状上更有效的观点。需要进一步研究针对这一特定目标群体的早期干预措施 (包括观察等待) 的有效性。

关键词: EMDR 疗法, 早期干预, 强奸, 性侵犯, PTSD

A recent population study among Dutch citizens found that 15% of women and 3% of men had experienced rape, that is, vaginal, oral, or anal sex without consent (De Graaf & Wijsen, 2017). Another study estimated the lifetime prevalence, averaged over genders, at 5.8% worldwide (Kessler et al., 2017). Exposure to rape has been found to contribute to the development of psychological problems, such as depression, dissociation, substance abuse, feelings of guilt and shame, and suicidal ideation (Aakvaag et al., 2016; Faravelli, Giugni, Salvatori, & Ricca, 2004; Galatzer-Levy, Nickerson, Litz, & Marmar, 2013; Tiihonen Möller, Bäckströ, Söndergaard, & Helström, 2014; Weaver et al., 2007). Victims of rape can also develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a mental health condition characterized by symptoms of intrusions, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and hyperarousal related to exposure to the traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992).

Studies have found that almost all rape victims experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress in the days following the event (Rothbaum et al., 1992) and about 40% will develop PTSD within three months (Elklit & Christiansen, 2010; Tiihonen Möller et al., 2014). The development of PTSD after rape is thus highly prevalent. PTSD has a substantial personal and societal impact, not only through the impairment caused by its symptoms but also because it is known to predict the development of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorders (Kessler, 2000). Collectively, these mental health problems cost nearly two trillion dollars per year in the US, which is two thirds of the total economic burden caused by rape (Peterson, DeGue, Florence, & Lokey, 2017). PTSD is also related to physical problems, including cardiovascular and gastrointestinal symptoms, chronic pain (Gupta, 2013), and pelvic floor problems (Karsten et al., 2020). Furthermore, rape victims who develop PTSD have an increased risk of revictimization, that is, experiencing new sexual assaults (Messman-Moore, Ward, & Brown, 2009). Thus, PTSD can catalyse a cycle of physical and mental health problems that each increases the societal impact and decrease victims’ quality of life.

Preventing the personal and public health burden of mental illnesses is complex because the cause and onset of disorders are difficult to determine. PTSD is an exception, as the disorder is initiated by a traumatic event, and the time of onset of its symptoms is often known (Magruder, McLaughlin, & Borbon, 2017). To this end, PTSD provides a unique possibility for early intervention to prevent the development and consequences of the disorder. A meta-analysis of early intervention after sexual assault, including RCTs on prolonged exposure, video intervention, and cognitive processing therapy, found a significantly greater reduction of post-traumatic stress symptoms after early intervention than standard care (Oosterbaan, Covers, Bicanic, Huntjens, & de Jongh, 2019). Despite this encouraging outcome, the authors emphasized that the evidence was based on only four studies and that the risk of bias in these early intervention studies was high, especially selection bias.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is one of the recommended treatments for PTSD once the diagnosis is established (International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Guidelines Committee [ISTSS], 2018; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2018). In recent years, several RCTs showed that, in non-sexual trauma victims and relative to no treatment, early intervention with EMDR therapy within six weeks post-trauma is efficacious in reducing post-traumatic stress (Jarero, Artigas, & Luber, 2011; Shapiro & Laub, 2015; Tarquinio et al., 2016). Yet, the effectiveness of EMDR therapy as an early intervention after rape still has to be established. Therefore, we conducted an RCT aimed to determine the effectiveness of EMDR therapy on psychological symptoms after rape. Our primary hypothesis was that individuals, who had very recently been raped and who received EMDR therapy between two and four weeks following this event, would demonstrate significantly lower levels of self-reported and clinician-reported post-traumatic stress symptoms at post-treatment and eight and 12-weeks post-rape follow-ups, relative to individuals who received treatment as usual (i.e. ‘watchful waiting’). Secondly, it was hypothesized that victims of recent rape who received EMDR therapy would demonstrate a significantly lower level of sexual and psychological dysfunction (i.e. general psychopathology, anxiety, depression and dissociative symptoms), and feelings of guilt and shame at post-treatment, and both follow-ups, than victims who received treatment as usual.

1. Method

1.1. Study design

Four sexual assault centres in the Netherlands collaborated in this RCT. Per centre, a randomization sequence was computer-generated. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the two study conditions on a 1:1 ratio: EMDR therapy or treatment as usual (TAU). Participation included assessments at four time points. For a detailed description of the study protocol, see Covers et al. (2019). Neither trial design nor eligibility criteria changed during the trial. The only adjustment to the study protocol was the decision to report PTSD diagnosis without further analysis1.

1.2. Participants

Victims of rape who contacted one of the participating sexual assault centres within one week after they experienced rape were screened for research participation. In this study, rape was defined as vaginal, oral, or anal penetration without consent, as reported by the victim. Victims younger than 16, victims with cognitive disabilities, and victims who did not speak Dutch were excluded from study participation. Also, victims who required immediate psychological care for psychoses, suicidal ideation, or addiction were excluded from the study. Additionally, in order to exclude those with pre-existing PTSD, victims who received concurrent trauma-focused treatment for prior experiences were excluded from the study. Exclusion was not based on symptom levels as most victims were expected to exhibit relatively high levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms immediately post-rape (Rothbaum et al., 1992; Steenkamp, Dickstein, Salters-Pedneault, Hofmann, & Litz, 2012; Tiihonen Moller 2014). Fifty-seven victims, including one male, agreed to participate in this study.

1.3. Procedures

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht and registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR6760). Upon admission to the sexual assault centres, victims received medical care and could be put in contact with the police. Victims also received psychoeducation about common reactions after rape by a case manager via telephone one day after admission to the centre. Between March 2018 and January 2020, victims of rape who contacted one of the participating sexual assault centres within one week after they experienced rape were screened for research participation during this call. The case manager screened for the exclusion criteria of the study using the information from the conversation with the victim. No instruments were used to assess the exclusion criteria. Victims who did not meet the exclusion criteria received a study information letter. The following day, the researcher contacted these victims for further information. After informed consent, subjects were randomly allocated to EMDR therapy or TAU. Both groups received their intervention between two and four weeks post-rape and were assessed at the following time points: pre-treatment at two weeks post-rape, post-treatment at one week after the treatment (4 to 5 weeks post-rape), and two follow-up assessments at eight and 12 weeks post-rape. The assessors were blinded to the intervention allocation. Subjects received a 20 euro incentive after concluding their participation, regardless of whether they completed all assessments. The CONSORT 2010 guideline (Schulz, Altman, & Moher, 2010) was followed for the reporting of this RCT.

1.4. Interventions

Subjects in the intervention arm of this study received 3.5 hours of EMDR therapy across two sessions. In EMDR therapy eye movements are used to reduce the vividness and emotionality of trauma memory (Shapiro, 2018). In the present study, the Dutch version of the standard eight-phased EMDR protocol (De Jongh & Ten Broeke, 2019; Shapiro, 2018) was used. The trauma memory was conceptualized as a memory lasting from a period of time from the rape until the day of treatment. This adaptation, derived from the EMDR Recent Traumatic Episode Protocol (R-TEP; Shapiro & Laub, 2008, 2014; Shapiro, 2012) pertains to minor changes to the wording of sentences in some phases of the EMDR standard protocol, including the memory of the trauma episode (i.e. the period of time of the rape until the day of treatment) and installation of the positive cognition and body scan related to the trauma episode rather than linked to the specific rape memory per se. Therapists were eight licenced psychologists who completed an accredited course of EMDR therapy and were trained in the application of the study protocol. Video recordings of the sessions were made for bimonthly supervision by two EMDR Europe accredited trainers in EMDR therapy ([author initials redacted for peer review]) and in order to determine treatment adherence. This treatment adherence was measured using an EMDR-specific treatment integrity checklist used in previous EMDR studies (e.g. Van den Berg et al., 2015). Twenty-five per cent of the 48 video recordings were assessed by two independent psychology graduates. There were no inconsistencies in these two assessments and treatment fidelity proved high (97%).

The control condition of the study entailed the sexual assault centres’ treatment as usual. This consisted of two telephone contacts of approximately 30 minutes with a case manager, who provided psychoeducation and emotional support in accordance with a watchful waiting protocol (NICE, 2018). This protocol is currently standard in all (16) sexual assault centres in the Netherlands and stipulates screening for post-traumatic stress symptoms at least two times during the first month post-rape and, if indicated, subsequent referral for evidence-based treatment. For the purpose of the present study, subjects in the control condition were not referred after watchful waiting by the case manager. Instead, watchful waiting ended at one-month post-rape. If needed, subjects from both study conditions with a high need for psychological treatment could be referred for therapy after the study by the researchers. If there was an urgent need for treatment during the study participation, subjects were referred immediately but excluded from further participation in the study.

1.5. Measures

For an overview of all outcome measures, the total score range and the internal consistency in the current study, see Table 1. For a complete description of the measures, we refer the reader to the study protocol (Covers et al., 2019). The use of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI; Rosen et al., 2000) was altered after data collection. The FSFI measured the presence and quality of sexual desires, arousal, and penetration. The total score of the FSFI can only be used for participants who have been sexually active during the study. Therefore, we used a combined score based on two domains (desire and satisfaction) of the FSFI that did not rely on sexual activity during the study.

Table 1.

Time of assessment and internal consistency per outcome measure

| Instrument | Total score range | Time of assessment | Internal consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | |||

| Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5; Boeschoten et al., 2014) | 0–80 | Post, 8, 12 | .889 |

| PTSD Checklist for the DSM 5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) | 0–80 | Pre, Post, 8, 12 | .940 |

| Psychological functioning | |||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) Depression scale | 0–21 | Pre, Post, 8, 12 | .859 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Anxiety scale | 0–21 | Pre, Post, 8, 12 | .893 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; De Beurs & Zitman, 2006) | 0–212 | Pre, 8, 12 | .972 |

| Dissociation Tension Scale (DTS; Stiglmayr et al., 2010) | 0–100 | Pre, Post, 8, 12 | .941 |

| Sexual functioning | |||

| Amsterdam Overactive Pelvic Floor Scale for Women (AOPFS; Van Lunsen & Van Laan, 2007) | 6–30 | Pre, 12 | .893 |

| Female Sexual Functioning Index (FSFI; Rosen et al., 2000) Total score | 1.6–36 | Pre, 12 | .972 |

| Female Sexual Functioning Index (FSFI) Desire and Satisfaction | 1.6–12 | Pre, 12 | .797 |

| Item on sexual desire (based on Tarquinio, Brennstuhl, Reichenbach, Rydberg, & Tarquinio, 2012) | 1–5 | Pre, 12 | NA |

| Guilt/shame | |||

| Items on feelings of guilt and shame (based on Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991) | 1–5 | Pre, 12 | NA |

Time of assessment is defined as pre-treatment (Pre), post-treatment (Post), follow-up at eight weeks post-rape and follow-up at 12 weeks post-assault. Internal consistency is calculated with Cronbach’s alpha. For all measures higher scores indicate more psychopathology, with the exception of the FSFI, where higher scores indicate less psychopathology. The CAPS-5 was not administered at the pre-treatment assessment in order to facilitate study participation.

1.6. Statistical analysis

Independent-samples t-tests and chi-square tests were executed to test for any differences in pre-treatment measures between non-completers (dropout at any point during the study including dropout before pre-treatment assessment) and completers (participation up to the last follow-up). To determine the effectiveness of EMDR therapy in reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms and other psychological dysfunction, a covariance pattern linear mixed model analysis (Liu, Rovine, & Molenaar, 2012) was conducted on the intention-to-treat sample while adjusting for pre-treatment assessment scores. Analyses including only assessment completers were not possible, since the small completers sample caused a lack of statistical power (Figure 1). Fixed effects were time, condition, and the interaction between time and condition. When significant condition effects were found, group differences over time were further analysed by pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. The effect of EMDR therapy on sexual dysfunction (FSFI, AOPFS, and sexual desire) and guilt/shame was analysed with ANCOVAs with pre-treatment assessment of the respective measures as covariates. For the analyses, BSI, DTS, and AOPFS scores were transformed using square root to adjust for non-normality. Any missing item scores were imputed using a two-way multiple imputation (Van Ginkel, Van der Ark, Sijtsma, & Vermunt, 2007). Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988). SPSS version 25 was used for all analyses.

Figure 1.

Attrition flow chart

2. Results

2.1. Attrition and baseline

Figure 1 shows the attrition of participants from enrolment to analysis. In the present study, one participant in the EMDR condition experienced an increase in suicidal ideation between pre-treatment and post-treatment assessments after which participation in the study was discontinued and psychological care was initiated. As the analyses of the present study are on an intention-to-treat basis, this participant was not excluded from the analyses.

A total of 37 participants completed the 12-week follow-up assessment. However, one of these participants was not available for the post-treatment assessment and 8-week follow-up assessment, and is therefore considered a non-completer in the dropout analysis. Assessments of non-completers (n = 21) did not differ from participants who completed all assessments (n = 36) with respect to age (t = −1.18, df = 55, p = .243), treatment allocation (χ2 = 0.14, p = .707), and relationship to the perpetrator (known vs unknown, χ2 = 0.24, p = .622). Participants who dropped out after completion of the pre-treatment assessment (i.e. missed any of the three post-treatment assessments but completed the pre-treatment assessment, n = 16) did not differ from those who completed all assessments (n = 36) in pre-treatment post-traumatic stress symptoms (PCL-5; t = .323, df = 50, p = .748) or general psychopathology symptoms (BSI; t = −0.55, df = 50, p = .584).

2.2. Demographic and clinical characteristics

The mean age of the 57 participants was 25.81 years (SD = 8.18) with no difference between the EMDR therapy condition (M = 25.52, SD = 7.93) and the TAU condition (M = 25.88, SD = 8.23; t = 0.161, df = 50, p = .872). Further participant characteristics are found in Table 2. The mean scores of all measures per assessment are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| EMDR |

TAU |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Relationship to perpetrator (known) | 20/27 | 74% | 20/25 | 80% |

| Prior sexual assault experience | 5/18 | 28% | 6/14 | 43% |

| Prior trauma-based treatment | 6/19 | 32% | 2/14 | 14% |

| Conscious during recent rape | 14/17 | 82% | 9/13 | 69% |

Variables were missing for some participants. n refers to the ratio of observed to measured.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviations of each outcome variable per assessment

| EMDR |

TAU |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Assessment | n | M | SD | n | M | SD |

| PCL-5 | Pre | 27 | 45.69 | 13.45 | 25 | 47.84 | 13.65 |

| Post | 22 | 32.10 | 16.89 | 20 | 37.95 | 11.26 | |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 24.49 | 18.53 | 19 | 32.57 | 18.31 | |

| 12 weeks | 20 | 22.09 | 16.41 | 17 | 23.29 | 17.94 | |

| CAPS-5 | Post | 22 | 28.95 | 14.60 | 19 | 33.05 | 10.63 |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 22.79 | 14.95 | 19 | 27.05 | 16.25 | |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 17.74 | 13.81 | 17 | 21.00 | 14.67 | |

| HADS Depression | Pre | 27 | 10.70 | 4.74 | 25 | 8.80 | 4.01 |

| Post | 21 | 8.48 | 4.06 | 20 | 8.95 | 3.76 | |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 7.63 | 4.70 | 19 | 7.00 | 4.43 | |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 6.68 | 4.83 | 17 | 6.06 | 4.87 | |

| HADS Anxiety | Pre | 27 | 13.00 | 4.71 | 25 | 11.92 | 4.34 |

| Post | 21 | 8.81 | 3.98 | 20 | 10.75 | 3.45 | |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 7.98 | 4.28 | 19 | 9.47 | 4.02 | |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 7.00 | 4.59 | 17 | 7.41 | 4.90 | |

| DTS | Pre | 27 | 30.03 | 23.26 | 25 | 25.53 | 19.39 |

| Post | 21 | 9.68 | 11.45 | 20 | 16.02 | 13.43 | |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 6.95 | 7.79 | 18 | 13.02 | 13.08 | |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 4.62 | 3.96 | 17 | 8.15 | 10.23 | |

| BSI | Pre | 27 | 88.26 | 44.35 | 25 | 89.06 | 39.08 |

| 8 weeks | 19 | 49.16 | 33.24 | 18 | 54.51 | 36.43 | |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 42.07 | 29.66 | 17 | 43.17 | 36.23 | |

| AOPFS | Pre | 27 | 11.35 | 4.61 | 24 | 11.61 | 3.21 |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 9.25 | 2.08 | 16 | 11.07 | 2.83 | |

| FSFI desire and satisfaction | Pre | 27 | 4.04 | 2.61 | 24 | 4.46 | 2.22 |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 5.46 | 3.05 | 16 | 5.91 | 2.55 | |

| Change in sexual desire | Pre | 27 | 2.00 | 1.49 | 25 | 2.32 | 1.49 |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 2.68 | 1.80 | 17 | 3.00 | 1.54 | |

| Guilt | Pre | 27 | 3.00 | 1.47 | 25 | 3.24 | 1.45 |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 1.42 | 0.84 | 17 | 1.94 | 0.97 | |

| Shame | Pre | 27 | 3.22 | 1.45 | 25 | 3.68 | 1.35 |

| 12 weeks | 19 | 1.74 | 0.81 | 17 | 2.59 | 1.28 | |

PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DTS = Dissociation Tension Scale; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; AOPFS = Amsterdam Overactive Pelvic Floor Scale for Women; FSFI = Female Sexual Functioning Index.

2.3. Early EMDR process

Among those who received EMDR therapy (n = 26), on average 5.92 target images (SD = 3.45, range 0–13) were treated with a SUD (subjective unit of disturbance) of zero. These targets include images of the assault and the aftermath, as well as images of future fears (‘Flashforward procedure’; de Jongh, 2015; Logie & De Jongh, 2014) and present triggers (‘Mental video check’; de Jongh, 2015; Shapiro, 2018). At eight-week post-rape, 47% (n = 9) of the participants in the EMDR condition and 58% (n = 11) of the participants in the TAU condition met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD1 according to the CAPS-5. At 12 weeks, PTSD could be diagnosed in 16% (n = 3) of the participants in the EMDR condition and 35% (n = 6) of the participants in the TAU condition.

2.4. Effectiveness of EMDR therapy

Across all outcome measures, the between-group effect sizes were small to medium (Table 4; Cohen, 1988). All between-group effect sizes indicate fewer symptoms for the EMDR condition than the TAU condition. Medium to large within-group effect sizes were found for the EMDR condition, and small to large for the TAU condition.

Table 4.

Between-group effect sizes at posttreatment and follow-up assessments and within-group effect sizes in Cohen’s d

| Between-group effect size |

Within-group effect size |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-treatment | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | Pre-treatment to post-treatment |

Pre-treatment to 8 weeks |

Pre-treatment to 12 weeks |

||||

| EMDR | TAU | EMDR | TAU | EMDR | TAU | ||||

| PCL-5 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 1.31 | 0.95 | 1.57 | 1.54 |

| CAPS-5 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.23 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| HADS Depression | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.61 |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.96 | 0.30 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 1.29 | 0.97 |

| DTS | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 1.24 | 0.59 | 1.33 | 0.76 | 1.52 | 1.12 |

| BSI | - | 0.15 | 0.03 | - | - | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.22 | 1.22 |

| AOPFS | - | - | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | 0.59 | 0.18 |

| FSFI desire and satisfaction | - | - | −0.16 | - | - | - | - | 0.50 | 0.61 |

| Sexual desire | - | - | −0.19 | - | - | - | - | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| Guilt | - | - | 0.57 | - | - | - | - | 1.32 | 1.05 |

| Shame | - | - | 0.79 | - | - | - | - | 1.26 | 0.83 |

Positive between-group effect sizes indicate that the EMDR condition scored lower than the control condition. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DTS = Dissociation Tension Scale; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; AOPFS = Amsterdam Overactive Pelvic Floor Scale for Women; FSFI = Female Sexual Functioning Index.

2.4.1. Post-traumatic stress symptoms

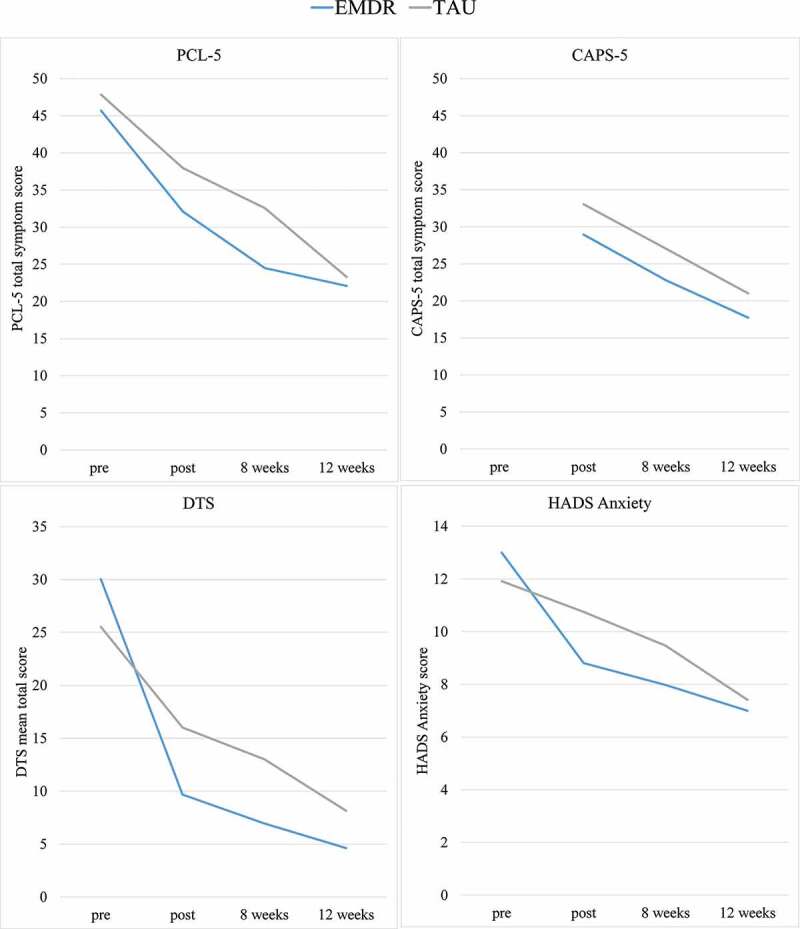

Figure 2 visualizes the changes in self-reported and clinician reported post-traumatic stress symptom scores per condition over time, reflecting a decrease in symptoms in both conditions. Table 5 shows the estimates of the effects of condition and time and the condition–time interaction effect from the analyses. For post-traumatic stress symptoms, the PCL-5 and the CAPS-5, the results showed no significant effect of the condition and no significant interaction effect of the condition and time from post-treatment to 12 weeks, meaning that there was no significant difference between the conditions in total post-traumatic symptom scores at any of these assessments. The effect of time was significant at 8 and 12 weeks compared to post-treatment for both outcomes with a decrease in total score over time.

Figure 2.

Mean scores for the EMDR and control conditions on self-reported (PCL-5) and clinician reported post-traumatic stress symptoms (CAPS-5), dissociative symptoms (DTS) and anxiety symptoms (HADS anxiety) at pre-treatment, post treatment, and eight and 12 week follow-ups

Table 5.

Estimate outcomes of mixed model analyses

| Intercept |

Pre-treatment |

Condition |

Time |

Condition-time interaction |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks | 12 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | ||||||||||||||||||

| Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

Est |

SE |

95% CI |

|

| PCL-5 | 8.40 | 7.17 | −6.08, 22.88 |

0.60** | 0.14 | 0.33, 0.88 |

−4.92 | 3.63 | −12.27, 2.43 |

−5.86* | 2.71 | −11.36, -0.37 |

−14.57** | 3.22 | −21.10, -8.04 |

0.43 | 3.82 | −7.31, 8.17 |

6.66 | 4.48 | −2.41, 15.74 |

| CAPS-5 | 33.05** | 2.96 | 27.06, 39.05 |

- | - | - | −4.10 | 4.05 | −12.28, 4.09 |

−6.00* | 2.20 | −10.45, -1.55 |

−11.80** | 2.83 | −17.54, -6.05 |

1.65 | 3.11 | −4.65, 7.95 |

1.84 | 3.94 | −6.14, 9.82 |

| HADS Depression | 2.72 | 1.48 | −0.27, 5.71 |

0.66** | 0.14 | 0.39, 0.94 |

−1.63 | 1.07 | −3.80, 0.54 |

−2.07** | 0.72 | −3.53, -0.60 |

−2.33* | 0.97 | −4.29, -0.38 |

1.23 | 1.02 | −0.84, 3.29 |

0.54 | 1.35 | −2.19, 3.27 |

| HADS Anxiety | 4.39** | 1.48 | 1.39, 7.39 |

0.51** | 0.11 | 0.30, 0.73 |

−2.25* | 0.95 | −4.17, -0.32 |

−1.39* | 0.62 | −2.65, -0.13 |

−2.97** | 0.91 | −4.82, -1.12 |

0.58 | 0.88 | −1.20, 2.37 |

1.19 | 1.27 | −1.39, 3.77 |

| BSI | −1.06 | 1.46 | −4.02, 1.91 |

0.85** | 0.15 | 0.55, 1.15 |

−0.04 | 0.64 | −1.34, 1.26 |

- | - | - | −0.93* | 0.38 | −1.69, -0.16 |

- | - | - | 0.39 | 0.51 | −0.65, 1.44 |

| DTS | 1.41* | 0.52 | 0.36, 2.46 |

0.46** | 0.09 | 0.28, 0.63 |

−1.14* | 0.44 | −2.02, -0.26 |

−0.58* | 0.26 | −1.12, −0.05 | −1.17** | 0.32 | −1.80, -0.53 |

0.13 | 0.37 | −0.62, 0.88 |

0.39 | 0.44 | −0.50, 1.28 |

The pre-treatment assessment of the measure was the covariate in the respective analyses. Reference categories are TAU condition and post-treatment assessment. Effects of BSI, and DTS are based on transformed data. BSI was not assessed at post-treatment, so the reference category is the 8 week follow-up. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; DTS = Dissociation Tension Scale; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory. *p < .05 **p < .01.

2.4.2. Psychological functioning

For HADS Anxiety (Figure 2 and Table 5), the results showed a significant effect of time at 8 and 12 weeks with decreasing HADS Anxiety scores over time compared to post-treatment. There was a significant effect of condition where the EMDR condition scored lower than the TAU condition at post-treatment. There was no significant condition–time interaction at 8 and 12 weeks. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant difference between conditions at post-treatment (Mdiff = 2.25, SE = 0.95, p = .023, 95% CI = [0.32, 4.17]) but not at eight weeks (Mdiff = 1.67, SE = 1.16, p = .158, 95% CI = [−0.68, 4.01]) or 12 weeks (Mdiff = 1.05, SE = 1.35, p = .440, 95% CI = [−1.68, 3.79]). Also, the DTS (Figure 2 and Table 5) showed a significant effect of time at eight and 12 weeks with decreasing scores over time compared to post-treatment. There was a significant effect of condition with lower scores for EMDR than TAU at post-treatment and no significant condition–time interaction. However, pairwise comparisons showed a significant difference between conditions at post-treatment (Mdiff = 1.14, SE = 0.44, p = .013, 95% CI = [1.18, 9.25]) and eight weeks Mdiff = 1.01, SE = 0.44, p = .029, 95% CI = [0.50, 8.73]), but the difference at 12 weeks was not significant (Mdiff = 0.75, SE = 0.37, p = .051, 95% CI = −0.10, 6.89]). Furthermore, both the BSI and HADS Depression scores showed no significant effect of condition and no significant condition–time interaction (Table 5). The effect of time was significant at 8 and 12 weeks with decreasing scores over time compared to post-treatment.

2.4.3. Sexual functioning, guilt and shame

Table 6 displays the results of the ANCOVA analyses. The results showed no significant effect for condition on the AOPFS scores (F(1, 35) = 1.71, p = .200) and the FSFI scores (F(1, 35) = 0.13, p = .719). No condition effect was found for change in sexual desire (F(1, 36) = 0.25, p = .618), guilt (F (1,36) = 0.71, p = .405), and shame (F(1, 36) = 1.45, p = .236) either.

Table 6.

Estimate outcome of ANCOVA analyses

| Intercept |

Pre-treatment |

Condition |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | |

| AOPFS | 2.48** | 0.66 | 1.14, 3.81 | 0.58** | 0.10 | 0.38, 0.77 | −0.19 | 0.20 | −0.59, 0.22 |

| FSFI desire and satisfaction | 2.99** | 0.91 | 1.13, 4.85 | 0.59** | 0.17 | 0.24, 0.93 | −0.30 | 0.84 | −2.01, 1.40 |

| Change in sexual desire | 1.86** | 0.56 | 0.73, 2.99 | 0.45 | 0.23 | −0.01, 0.91 | −0.27 | 0.54 | −1.37, 0.83 |

| Guilt | 0.65 | 0.33 | 0.00, 1.33 | 0.29** | 0.10 | 0.08, 0.50 | −0.25 | 0.29 | −0.84, 0.35 |

| Shame | 0.69 | 0.44 | −0.20, 1.57 | 0.36** | 0.13 | 0.10, 0.63 | −0.43 | 0.36 | −1.15, 0.29 |

The pre-treatment assessment of the measure was the covariate in the respective analyses. Reference category is TAU condition. Effects of AOPFS are based on transformed data. AOPFS = Amsterdam Overactive Pelvic Floor Scale for Women; FSFI = Female Sexual Functioning Index. *p < .05 **p < .01.

4. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial aimed to investigate the effectiveness of early intervention with EMDR therapy in reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms, as well as symptoms of other psychological and sexual dysfunction, and feelings of guilt and shame in victims of rape. The results do not support the primary study hypothesis in that victims of rape who received EMDR therapy between two and four weeks post-rape did not demonstrate less post-traumatic stress symptoms at post-treatment and 8- and 12-week follow-ups than victims who received watchful waiting (TAU). The study found large reductions in post-traumatic stress symptoms between two and 12 weeks post-rape in both study conditions as evident in effect sizes.

These results contrast with a systematic review and meta-analysis of early intervention after sexual assault (Oosterbaan et al., 2019), where interventions prior to three months post-rape were found to be more effective than the control conditions in reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms. Notably, the studies in this meta-analysis differed from the present study in methodology. Indeed, an RCT on early intervention with prolonged exposure for victims of rape did find a significant difference in post-traumatic stress symptoms at 12 weeks post-rape between the intervention and control condition (Rothbaum et al., 2012). However, the control condition in that study was a no treatment control condition. In contrast, the present study used a TAU control condition (watchful waiting) consisting of psycho-education, active listening, and well-informed advise. An RCT on early intervention using cognitive processing therapy after rape by Nixon, Best, Beatty, and Weber (2016), which was also carried out at a sexual assault centre and used a similar TAU control condition as in the present study, found similar between-group effect sizes as the present study (Cohen’s d PCL-5 at post-treatment = 0.30 and at 12 weeks post-rape = 0.16, indicating fewer symptoms for the intervention condition than the control condition). Moreover, the within-group effect size between 2 and 12 weeks post-rape associated with the application of EMDR therapy in the present study was very large (Cohen’s d PCL-5 = 1.57; Cohen, 1988). This effect size is larger than the one found by Nixon et al. (2016; Cohen’s d PCL-5 = 0.95), even though their intervention consisted of six sessions compared to our two sessions. Noteworthy, however, the participants in the watchful waiting (TAU) condition also decreased in post-traumatic stress symptoms over time (Cohen’s d PCL-5 = 1.57). Although some natural regression of acute stress symptoms during the first months post-rape was expected (Steenkamp et al., 2012), the results might suggest that natural regression is a particularly powerful factor in this target group (i.e. in both conditions). It is of note that the findings of the present study support a recent meta-analysis of early intervention after any type of trauma (Roberts et al., 2019), which found early interventions to be no more effective as treatment-as-usual on post-traumatic stress symptoms at post-treatment and longer follow-ups, when intervention was offered to all individuals exposed, regardless of symptomatology.

The results of the present study were also not supportive of the secondary hypothesis in that victims of rape who received EMDR therapy did not report significantly less sexual dysfunction, psychological dysfunction (which included symptoms of general psychopathology, anxiety, depression, and dissociation), and feelings of guilt and shame than victims who received watchful waiting (TAU). These symptoms reduced strongly over time in both study conditions. Although EMDR therapy was found to be more effective than watchful waiting (TAU) in reducing symptoms of anxiety and dissociation at post-treatment, we were unable to find sufficient evidence to determine a lasting surplus effect of EMDR therapy across 12 weeks post-rape on these symptom clusters. This initial effect of EMDR therapy on anxiety and dissociation may be caused by the treatment’s focus on traumatic memories. Specifically, EMDR aimed at individuals’ flashforwards (i.e. images of future fears) and the implementation of a mental video check (i.e. anxiety and tensions about present events) was used as additional interventions meant to treat present and anticipatory fears, such as the fear of being assaulted again by the same or other perpetrator. This focus may have resulted in a stronger reduction in anxiety and dissociative symptoms. Still, victims of the watchful waiting (TAU) condition also showed reduced symptoms of anxiety and dissociation across time, and at 12 weeks post-rape these symptoms were equal across study conditions. Finally, whereas no prior research has studied the effect of early intervention after rape on symptoms of anxiety or dissociation, nor sexual dysfunction and feelings of guilt and shame, two RCTs have studied the effect of early intervention on symptoms of depression (Resnick et al., 2007; Rothbaum et al., 2012). Our findings on symptoms of depression are in contrast to those studies in which early interventions were found to be more effective in reducing symptoms of depression in victims of sexual assault than no treatment (Resnick et al., 2007; Rothbaum et al., 2012). The lack of between-group effect in the present study may be explained by the focus of watchful waiting on normalizing stress responses experienced during and after rape, such as genital response and tonic immobility. Also, the encouragement of social sharing, as well as the involvement of important others and educating these persons to give the victim social support and acknowledgement, is known to have a positive effect on symptoms of depression.

Lastly, an important outcome of the present study is that EMDR therapy is a safe option for early intervention after rape, even for victims who had prior experience with sexual abuse. Only one participant discontinued participation due to increased suicide ideation. No other (serious) adverse events were found.

The present study has several limitations. First, the EMDR intervention was compared to a TAU control condition. This means that no comparison could be made between EMDR therapy and no treatment or between watchful waiting (TAU) and no treatment. The alternative to a waitlisted control condition was believed to be unethical in this study considering the high risk of developing psychopathology after a rape. Moreover, for clinical practice, it can be argued that the most relevant question is whether EMDR therapy is more effective than the existing care, especially given the additional expertise and financial costs that EMDR therapy requires. A second limitation of the present study was the high dropout rate. Although this study included 52 participants, only 36 completed all assessments, resulting in a drop-out rate of 31%. This rate is comparable to those in other early intervention studies with rape victims (Miller, Cranston, Davis, Newman, & Resnick, 2015; Nixon et al., 2016; Resnick et al., 2007), and may be related to avoidant coping behaviour. Yet, high drop-out rates are likely to cause attrition bias. However, in the present study, the data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. Also, the non-completers analysis found no difference between completers and dropouts in age, relationship to perpetrator, posttraumatic stress symptoms or general psychopathology. Therefore, we can assume that attrition bias is minimalized. Still, there was insufficient power for a subsequent completers analysis or other sub-sample tests. A third limitation is the sample of the present study. Although the sample size is small, prior power analysis indicates sufficient power for the analyses. However, the sample is mainly female, making it difficult to generalize the results in other genders. Yet, there is currently no evidence to suggest gender differences in the psychological care needs of rape victims (Covers, Teeuwen, & Bicanic, 2020).

We recommend that future research focus on the efficacy of watchful waiting as early intervention after rape, as it is more cost-effective than EMDR and equally effective in reducing post-traumatic psychopathology. In their study on brief cognitive-behavioural therapy (B-CBT) as early intervention after assault, Foa, Zoellner, and Feeny (2006) found no difference in post-traumatic stress symptoms at three months post-trauma between those who received B-CBT, supportive counselling, or no treatment. Although this study did not differentiate between victims of sexual and non-sexual assault, its results suggest that there is no added value in supportive counselling over no treatment. However, in contrast to watchful waiting, their supportive counselling protocol refrained from discussing trauma-related symptoms nor the processing of the traumatic event with the victims (Foa et al., 2006). As inadequate processing of information regarding the traumatic event is seen as the cause of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), adding elements to the protocol in support of adequate processing might result in different outcomes. Additionally, research suggests that psycho-education about trauma-related symptoms can reduce the development of these symptoms (Miller et al., 2015).

In conclusion, the present study found early intervention with EMDR therapy to be no more effective than watchful waiting for psychological problems, including post-traumatic stress symptoms, in victims of rape. Due to its cost-effectiveness, the present study supports the current guidelines that recommend watchful waiting for sexual assault victims (NICE, 2018) which entails that psychological symptoms are monitored, and psychoeducation and support are provided during the first month post-rape.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Achmea Association Victims & Society, Innovatiefonds Zorgverzekeraars, EMDR Research Foundation, Vereniging EMDR Nederland, and PAOS fonds.

Note

PTSD diagnosis was assessed using the CAPS-5. Group-differences in PTSD diagnoses could not be analysed due to a lack of statistical power. We therefore refrained from all inference based on the proportion of PTSD diagnoses.

Disclosure of statement

All authors have contributed to this study, registered in the Dutch trial register (www.trialregister.nl) under NTR6760. All authors read and approved this manuscript. A.J receives income from published books on EMDR therapy. C.R and A.J. receive income from training professionals in EMDR. Other authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MC, upon reasonable request. Due to the nature of this study and to protect the privacy of its participants, demographics including age and gender will not be made available.

References

- Aakvaag, H. F., Thoresen, S., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Dyb, G., Røysamb, E., & Olff, M. (2016). Broken and guilty since it happened: A population study of trauma-related shame and guilt after violence and sexual abuse. Journal of Affective Disorders, 204, 16–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Boeschoten, M. A., Bakker, A., Jongedijk, R. A., Van Minnen, A., Elizinga, B. M., Rademaker, A. R., & Olff, M. (2014). Clinician administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 - Nederlandstalige versie. Arq Academy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Covers, M. L. V., De Jongh, A., Huntjens, R. J. C., De Roos, C., Van Den Hout, M., & Bicanic, I. A. E. (2019). Early intervention with eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to reduce the severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms in recent rape victims: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10, 1632021. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1632021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covers, M. L. V., Teeuwen, J., & Bicanic, I. A. E. (2020). Male victims at a Dutch sexual assault centre: A comparison to female victims in characteristics and service use [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beurs, E., & Zitman, F. G. (2006). The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Reliability and validity of a practical alternative to SCL-90. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 61, 120–141. http://www.researchgate.net [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf, H., & Wijsen, C. (2017). Sexual health in the Netherlands 2017 [Seksuele gezondheid in Nederland 2017]. Retrieved from https://www.rutgers.nl/sites/rutgersnl/files/PDF-Onderzoek/Seksuele_Gezondheid_in_NL_2017_23012018.pdf

- de Jongh, A. (2015). EMDR therapy for specific fears and phobias: The Phobia protocol. In Luber M. (Ed.), Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: EMDR scripted protocols and summary sheets. Treating anxiety obsessive-compulsive, and mood-related conditions (pp. 9–40). Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh, A., & Ten Broeke, E. (2019). Handbook EMDR: A protocolled treatment for the consequences of psychotrauma. Pearson Assessment and Information B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elklit, A., & Christiansen, D. M. (2010). ASD and PTSD in rape victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(8), 1470–1488. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli, C., Giugni, A., Salvatori, S., & Ricca, V. (2004). Psychopathology after rape. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1483–1485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Rothbaum, B. O., Riggs, D. S., & Murdock, T. B. (1991). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 715–723. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2006). An evaluation of three brief programs for facilitating recovery after assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(1), 29–43. doi: 10.1002/jts.20096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Nickerson, A., Litz, B. T., & Marmar, C. R. (2013). Patterns of lifetime PTSD comorbidity: A latent class analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 30(5), 489–496. doi: 10.1002/da.22048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M. A. (2013). Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 25(1), 86–99. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.736367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Guidelines Committee . (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment guidelines methodology and recommendations. Author. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarero, I., Artigas, L., & Luber, M. (2011). The EMDR protocol for recent critical incidents: Application in a disaster mental health continuum of care context. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 5(3), 82–94. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.5.3.82 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten, M. D. A., Wekker, V., Bakker, A., Groen, H., Olff, M., Hoek, A., … Roseboom, T. J. (2020). Sexual function and pelvic floor activity in women: The role of traumatic events and PTSD symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1764246. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1764246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C. (2000). Post-traumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61, 4–12. https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/trauma/ptsd/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-burden-individual-society/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S., Rovine, M. J., & Molenaar, P. C. M. (2012). Selecting a linear mixed model for longitudinal data: Repeated measures analysis of variance, covariance pattern model, and growth curve approaches. Psychological Methods, 17(1), 15–30. doi: 10.1037/a0026971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie, R., & De Jongh, A. (2014). The ‘flashforward procedure’: Confronting the atastrophe. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(1), 25–32. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.8.1.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., & Borbon, D. L. E. (2017). Trauma is a public health issue. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1375338. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore, T. L., Ward, R. M., & Brown, A. L. (2009). Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(3), 499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. E., Cranston, C. C., Davis, J. L., Newman, E., & Resnick, H. (2015). Psychological outcomes after a sexual assault video intervention. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 11(3), 129–136. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder: NICE guideline. Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R. D. V., Best, T., Beatty, L., & Weber, N. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of acute stress disorder following sexual assault: A randomised effectiveness study. Behaviour Change, 33, 232–250. doi: 10.1017/bec.2017.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbaan, V., Covers, M. L. V., Bicanic, I. A. E., Huntjens, R. J. C., & de Jongh, A. (2019). Do early interventions prevent PTSD? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of early interventions after sexual assault. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1682932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C., DeGue, S., Florence, C., & Lokey, C. N. (2017). Lifetime economic burden of rape among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52, 691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, H., Acierno, R., Waldrop, A. E., King, L., King, D., Danielson, C., … Kilpatrick, D. (2007). Randomized controlled evaluation of an early intervention to prevent post-rape psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2432–2447. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N. P., Kitchiner, N. J., Kenardy, J., Robertson, L., Lewis, C., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Multiple sessions early psychological interventions for the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006869.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, C., Brown, J., Heiman, S., Leiblum, R., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., … D’Agostino, R. (2000). The female sexual function index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26, 191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B. O., Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Murdock, T., & Walsh, W. (1992). A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 455–475. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B. O., Kearns, M. C., Price, M., Malcoun, E., Davis, M., Ressler, K. J., … Houry, D. (2012). Early intervention may prevent the development of PTSD: A randomized pilot civilian study with modified prolonged exposure. Biological Psychiatry, 72, 957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., & Moher, D.; for the CONSORT group (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Medicine, 7(3), e1000251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E. (2012). EMDR and early psychological intervention following trauma. European Review of Applied Psychology, 62(4), 241–251. doi: 10.1016/J.ERAP.2012.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E., & Laub, B. (2008). Early EMDR intervention (EEI): A summary, a theoretical model, and the recent traumatic episode protocol (R-TEP). Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2(2), 79–96. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.2.2.79 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E., & Laub, B. (2014). The recent traumatic episode protocol (R-TEP): An integrative protocol for early EMDR intervention (EEI). In Luber M. (Ed.), Implementing EMDR early mental health interventions for man-made and natural disasters. Models scripted protocols, and summary sheets (pp. 193–215). Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, E., & Laub, B. (2015). Early EMDR intervention following a community critical incident: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 9(1), 17–27. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.9.1.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, M. M., Dickstein, B. D., Salters-Pedneault, K., Hofmann, S. G., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Trajectories of PTSD symptoms following sexual assault: Is resilience the modal outcome? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(4), 469–474. doi: 10.1002/jts.21718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiglmayr, C., Schimke, P., Wagner, T., Braakmann, D., Schweiger, U., Sipos, V., … Kienast, T. (2010). Development and psychometric characteristics of the dissociation tension scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(3), 269–277. doi: 10.1080/00223891003670232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarquinio, C., Brennstuhl, M. J., Reichenbach, S., Rydberg, J. A., & Tarquinio, P. (2012). Early treatment of rape victims: Presentation of an emergency EMDR protocol. Sexologies, 21(3), 113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2011.11.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarquinio, C., Rotonda, C., Houllé, W. A., Montel, S., Rydberg, J. A., Minera, L., & Alla, F. (2016). Early psychological preventive intervention for workplace violence: A randomized controlled explorative and comparative study between EMDR-recent event and critical incident stress debriefing. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(11), 787–799. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2016.1224282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen Möller, A., Bäckströ, T., Söndergaard, H. P., & Helström, L. (2014). Identifying risk factors for PTSD in women seeking medical help after rape. PloS One, 9(10), e111136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, D. P. G., de Bont, P. A. J. M., van der Vleugel, B. M., De Roos, C., De Jongh, A., van Minnen, A., & van der Gaag, M. (2015). Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus waiting list for post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(3), 259–267. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ginkel, J. R., Van der Ark, L. A., Sijtsma, K., & Vermunt, J. K. (2007). Two-way imputation: A Bayesian method for estimating missing scores in tests and questionnaires, and an accurate approximation. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 51(8), 4013–4027. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2006.12.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lunsen, R. H. W., & Van Laan, E. (2007). Amsterdam hyperactive pelvic floor scale- Women (AHPFS-W). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). National Center for PTSD. Retreieved from www.ptsd.va.gov [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, T., Allen, J., Hopper, E., Maglione, M. L., McLaughlin, D., McCullough, M. A., … Brewer, T. (2007). Mediators of suicide ideation within a sheltered sample of raped and battered women. Health Care for Women International, 28(5), 478–489. doi: 10.1080/07399330701226453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MC, upon reasonable request. Due to the nature of this study and to protect the privacy of its participants, demographics including age and gender will not be made available.