Abstract

School suspension is a common form of punishment in the United States that is disproportionately concentrated among racial minority and disadvantaged youth. Labeling theories imply that such stigmatized sanctions may lead to interpersonal exclusion from normative others and greater involvement with antisocial peers. I test these propositions in the context of rural schools by (1) examining the association between suspension and discontinuity in same-grade friendship ties, focusing on three mechanisms implied in labeling theories: rejection, withdrawal, and physical separation; (2) testing the association between suspension and increased involvement with antisocial peers; and (3) assessing whether these associations are stronger in smaller schools. Consistent with labeling theories, I find suspension associated with greater discontinuity in friendship ties, based on changes in the respondents’ friendship preferences and self-reports of their peers. Findings are also consistent with changes in perceptual measures of exclusion. Additionally, I find suspension associated with greater involvement with substance-using peers. Some but not all of these associations are stronger in smaller rural schools. Given the disproportionate distribution of suspension, my findings suggest an excessive reliance on this exclusionary form of punishment may foster inequality among these youth.

Keywords: labeling theory, peer networks, school suspension, social exclusion

The emphasis on crime control over much of the past half-century did more than fill our penal institutions; it also left empty desks in our classrooms. School suspension is a common response to classroom misbehavior in the United States and is heavily concentrated among racial minority and disadvantaged youth (Hirschfield, 2018a; Payne & Welch, 2010; Vanderhaar, Petrosko, & Muñoz, 2015; Welch & Payne, 2012). Excessive reliance on suspension is problematic because it excludes students from school activities and puts a mark on their academic records, potentially leading to further disengagement and lower educational attainment (Balfanz, Byrnes, & Fox, 2015; Morris & Perry, 2016; Pyne, 2019).

This weakened institutional attachment following suspension is consistent with labeling theories (Goffman, 1963; Lemert, 1951, 1967; Paternoster & Iovanni, 1989), which imply that stigmatizing sanctions can foster social exclusion, defined as the process of being pushed out of conventional society (Foster & Hagan, 2015). A focus on institutional exclusion is important, but labeling theories make clear that exclusion may also be interpersonal. I refer to interpersonal exclusion as a deterioration of relationships with normative others due to punishment. One of the relationships most relevant to students are friendships with peers they interact with most from year to year—those in their own grade. Such friendships are the medium by which children develop social skills and learn age-graded tasks. Indeed, having normative friends in one’s grade may be an early source of social capital (Coleman, 1988; Stanton-Salazar & Dornbusch, 1995), promoting outcomes like school achievement, emotional wellbeing, and behavioral adjustment (Crosnoe, 2000; Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). In contrast, exclusion from such friends may be accompanied by greater involvement with antisocial peers (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Laird et al., 2001).

If suspension is associated with exclusion from same-grade friends, this should be more apparent in settings where it is more stigmatizing. In disadvantaged urban areas, prior research suggests juvenile sanctions are “normalized” experiences (Hirschfield, 2008; Nolan, 2011). Small-town or rural areas, on the other hand, are often characterized by factors that reinforce social norms and may increase costs of a deviant label. These include greater network density or closure, more time spent with neighbors, and a larger share of ties to family and kin (Beggs, Haines, & Hurlbert, 1996; Coleman, 1988; Fischer, 1982; Marsden & Srivastava, 2012; Osgood & Chambers, 2000; Smith, 2003). To capture such a setting, I depart from the urban focus dominating school punishment research (e.g., Mittleman, 2018; Pyne, 2019) by relying on a predominantly rural sample. Rural schools vary in size, but smaller rural schools offer suspended youth less anonymity than larger rural schools can. Therefore, I also assess the extent to which associations between suspension and friendship outcomes are greater in smaller rural schools.

In this study, I extend prior labeling research in school contexts by moving beyond a focus on weakened institutional attachment or behavior outcomes (i.e., secondary deviance; Lemert, 1951; Wolf & Kupchik, 2017) to test whether suspension in a predominantly rural sample is followed by interpersonal exclusion from same-grade friends. I use a unique dataset of self-reports on behaviors and friendship preferences from students and their peers as they move from sixth to ninth grade. First, I examine the association between suspension and discontinuity in friendship ties. In doing so, I focus on three mechanisms of interpersonal exclusion implied in labeling theories: rejection, withdrawal, and separation. Second, I test the association between suspension and increased involvement with antisocial peers. Third, I assess the extent to which these associations are stronger in smaller schools.

BACKGROUND

SCHOOL SUSPENSION AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION

Suspension is not a rare experience in the US. Each year, 2.6 million children and adolescents are temporarily removed from school due to out-of-school suspension, and 2.7 million are excluded from class due to in-school suspension (Office of Civil Rights, 2018). Reform efforts have led to recent declines in some states (Loveless, 2017), but overall rates are still high, particularly for disadvantaged and racial minority students. This is not because juvenile crime rates are high but because suspension is often in response to minor misbehavior like classroom disruptions and attendance problems (Kupchik, 2010; Morris & Perry, 2017; Skiba et al., 2014). This is problematic because a growing body of research suggests suspension may be harmful for child and adolescent development (Cuellar & Markowitz, 2015; Hemphill, Toumbourou, Herrenkohl, McMorris, & Catalano, 2006; Jacobsen, Pace, & Ramirez, 2019; Mittleman, 2018; Morris & Perry, 2016; Perry & Morris, 2014).

One way that suspension may be harmful is through social exclusion. This concept, defined as “the structural condition of being shut out from conventional society” (Foster & Hagan, 2015: 136) is generally conceptualized as weakened attachment to important social institutions following an official sanction. Prior research on this topic has often focused on institutional rejection of those with a criminal history. For example, formerly incarcerated individuals may be barred from housing, legal employment, or adequate healthcare (Geller & Curtis, 2011; Pager, 2003; Lara-Millán, 2014). They may also exclude themselves (institutional withdrawal, or “system avoidance”) by minimizing involvement with schools, hospitals, or other institutions that keep formal records, out of fear of further apprehension or having their record discovered (Brayne, 2014; Goffman, 2009; Haskins & Jacobsen, 2017; Lageson, 2016).

Suspension also involves institutional exclusion. Not only are students physically separated from their classroom or school, they are formally excluded by a mark on their school records. School personnel who become aware of a student’s suspension history may lower their expectations or increase surveillance of the student (Ferguson, 2001; Weissman, 2015). Sensing or fearing these administrative reactions, previously suspended students may lower their trust in school personnel (Pyne, 2019) or disengage from school activities. These exclusionary processes may then be perpetuated into later grades and even beyond secondary school. For example, many high schools send discipline information to colleges (Weissman & NaPier, 2015), and college applications often inquire about suspension history. This may partly explain why suspension is associated with lower likelihood of school completion and postsecondary enrollment (Balfanz et al., 2015; Noltemeyer, Ward, & Mcloughlin, 2015).

INTERPERSONAL EXCLUSION

This institution-focused conceptualization of social exclusion is important for understanding consequences of excessive crime control for social inequality; however, it leaves out another type of exclusion often implied by theorists but rarely examined empirically. Lemert (1967: 252) describes exclusion as a “process that begins with persistent interpersonal difficulties between the individual and … other persons in the community.” Whereas institutional exclusion refers to a person’s weakened bonds to institutions, I refer to interpersonal exclusion as a weakening of ties to members of an individual’s social network following punishment. For example, some research suggests suspension may strain family relationships through stress (e.g., by interrupting parent work schedules) or embarrassment (Dunning-Lozano 2018; Kupchik 2016; Mowen 2017). I extend this work by examining suspended students’ weakened or severed ties to friends in their school. Friends in school are important because they provide the context in which children and adolescents learn social and behavioral skills that are critical for healthy development. Conforming friends encourage school adjustment and achievement (Crosnoe, 2000; Hartup & Stevens, 1997). They may also transmit knowledge from parents and mentors about appropriate classroom behavior, or share information such as how to prepare for college (Coleman, 1988; Stanton-Salazar & Dornbusch, 1995). Such friendships may be particularly important in rural areas where families and schools often have fewer economic or institutional resources (Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 2001; Nelson, 2016; Roscigno, 2006). I focus on friendships among same-grade peers because the youth in one’s grade represent a consistently present audience and pool of potential friends in which to examine changes in ties from year to year. I distinguish three ways that interpersonal exclusion may occur following suspension: rejection, withdrawal, and physical separation.

Rejection

In labeling theories, rejection refers to reactions of conforming individuals toward stigmatized others. It occurs when “normals” circumvent encounters with formerly sanctioned individuals out of uneasiness or to avoid guilt by association (Goffman, 1963). It also occurs when interactions with formerly sanctioned persons become less friendly or more restrictive to protect individual or group values (Lemert, 1967). Consistent with this idea, prior research suggests suspension may be more common among students with lower status among their peers (Kupersmidt & Coie, 1990). Importantly, rejection is defined as a response to the sanctioned individuals, rather than as a reaction to their behavior (Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, 1987). It would be evident if Classmates A and B respond to Student C’s suspension by no longer considering themselves to be C’s friends because C is a “bad kid,” not because C’s misbehavior was inappropriate.

Withdrawal

The concept of withdrawal characterizes the behavior of a stigmatized individual toward others, either out of fear of rejection or to avoid uncomfortable encounters (Goffman, 1963; Link, 1987; Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989). People are often socialized to believe that sanctioned individuals are dangerous or dishonest (Hirschfield & Piquero, 2010; McNulty & Roseboro, 2009). In the context of suspension, children may see how other suspended students have been excluded and come to believe suspension is for troublemakers. These stereotypes likely take on personal significance when students are suspended; they may anticipate strained interactions with normative peers and withdraw as a means of defense. Withdrawal would be evident if, following a suspension, Student C no longer prefers Classmates A or B as friends because C fears they may now view C as a troublemaker.

Rejection and withdrawal from peers may be more likely if the suspension is repeated. Lemert (1951: 76) suggests repeated sanctions for minor misbehavior facilitate “ingrouping and outgrouping” between sanctioned individuals and normative others until “a stigmatizing of the deviant occurs in the form of name calling, labeling, or stereotyping.” Thus, societal reactions accumulate as the sanction is experienced multiple times, amplifying the deviant label (Sampson & Laub, 1997). Most suspensions last no more than a few days (Shollenberger, 2015) but they are often repeated, even within the same year. Indeed, about four in ten suspended students are suspended multiple times in the same year (Office of Civil Rights, 2018). Having multiple suspensions could be a stronger signal that peers should avoid a suspended student, or it may reify the student’s expectations of rejection, increasing their likelihood of withdrawal. Therefore, suspension may be more strongly associated with rejection and withdrawal for students who have experienced it multiple times. This would be similar to prior findings that suspension is more strongly associated with a subsequent arrest when it is repeated (Mowen & Brent, 2016).

Separation

Rejection and withdrawal are responses to stigma, but interpersonal exclusion may also occur due to the physical separation the sanction entails. For example, prior research finds lengthy or repeated prison or jail stays, which involve separation from partners and children, associated with weakened family ties (Massoglia, Remster, & King, 2011; Turney & Wildeman, 2013). Suspension is not jail, but it involves separating students from their peers at school by removing them from school grounds or segregating them in an alternative classroom setting. Long or reoccurring suspensions cause students to miss out on shared experiences with other students. For example, in a qualitative study of the families of suspended youth, one boy reports that the time away from school during his suspensions caused him to lose contact with school peers (Kupchik 2016:58). Suspension may therefore weaken relationships with friends at school, independent of the level of stigma. In sum, suspension should be associated with discontinuity in friendships from the previous year, and some of this may be due to rejection and withdrawal; but part should also be explained by lengthy or repeated separation from friends.

INCREASED INVOLVEMENT WITH ANTISOCIAL PEERS

The processes described thus far imply that stigmatizing forms of punishment push an individual away from normative networks and increase the attractiveness, or pull, of marginalized and delinquent networks (Bernburg, Krohn, & Rivera, 2006). This suggests suspension may be associated with less involvement with peers who promote normative development and more involvement with peers who, according to a long history of criminological research on peer influence, may facilitate delinquency (McGloin, 2009; Ragan, 2014; Sutherland, 1947). Peers who are already more involved in antisocial behavior may be more accepting of the deviant label ascribed by the suspension. These may be current antisocial friends or other suspended peers with whom the student interacts during an in-school suspension, including from other grades. They may also be youth the student spends time with during an out-of-school suspension (Quin & Hemphill, 2014), such as older youth not in school, which some research associates with deviance (Harding, 2009). These changes should be evident in the changes in behavioral composition of networks following punishment. If suspension is followed by interpersonal exclusion from normative peers and greater involvement with other suspended or delinquent students, it should be associated with an increase in the average level of antisocial behavior among friends, such as would occur if more of the suspended student’s friends were involved in antisocial behavior than before.

STRONGER ASSOCIATIONS AMONG STUDENTS IN SMALLER RURAL SCHOOLS

Suspension may not be associated with peer exclusion equally across rural youth. In particular, students who are suspended in smaller schools may be more affected by stigma. Rural schools are, on average, smaller than urban schools (Lippman, Burns, & McArthur, 1996), but within rural settings, schools vary widely in size.1 As the number of students in a school declines, the level of anonymity the school can provide also diminishes. Smaller schools offer less anonymity because more peers know each other as classmates, friends, or in other ways. A small school in a rural school district means that school peers may be relatives, members of the same religious congregation, or their parents may be coworkers (Beggs et al., 1996). Indeed, prior research finds greater connectedness in smaller relative to larger rural schools (Temkin, Gest, & Osgood, 2018; see also Allcott, Karlan, Möbius, Rosenblat, & Szeidl, 2007). More ties among peers may facilitate the spread of news of the suspension and could mean higher social costs for suspended youth in smaller schools. For example, parents may discourage their child from spending time with a peer whom they heard was suspended. In sum, suspension may be more strongly associated with peer exclusion among students in smaller rural schools. It may also be more strongly associated with involvement with antisocial peers. This is because in smaller grades, exclusion from conforming friends leaves suspended youth with even greater constraints in friendship selection, potentially amplifying involvement with antisocial peers.

ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATIONS

Weakened Institutional Attachment

It is possible that discontinuity in friendship ties following suspension is due to weakened institutional attachment instead of the mechanisms I have described. Students may be less likely to maintain ties to conforming peers (and vice versa) not because of the stigma or separation associated with the suspension itself but because of the negative effects suspension may have on school engagement and achievement (Morris & Perry, 2016; Pyne, 2019; but see Kinsler, 2013). Lower achieving students experience more peer exclusion and have fewer same-grade friends, though evidence in rural schools is mixed (Austin & Draper, 1984; Flashman, 2012). Thus, it is important for examinations of interpersonal exclusion following suspension to account for weakened institutional attachment.

Spuriousness

An association between suspension and friendship discontinuity may also be due to spuriousness, rather than to an effect of the former on the latter. Friendship ties change from year to year for many reasons such as transferring schools (Felmlee, McMillan, Rodis, & Osgood, 2018), joining a sports team (Eder & Kinney, 1995), or engaging in certain behaviors. Some behaviors like substance use are associated with popularity, or increases in friendship ties (Moody, Brynildsen, Osgood, Feinberg, & Gest, 2011), but others like delinquency and physical aggression are associated with fewer friends (Dodge, 1983; Rulison, Kreager, & Osgood, 2014) and also increase the risk of suspension. This implies that any discontinuity in friendship ties following suspension may not be due to suspension itself but to characteristics correlated with suspension. Indeed, students who are at risk of suspension already feel less connected or accepted by school peers (Pyne, 2019). They are also more disadvantaged and may have difficulty maintaining ties due to issues like residential mobility (South, Haynie, & Bose, 2007), longer distances to school (particularly in rural communities; Fox, 1996), or other stigmas already present. For example, parental criminal justice involvement is associated with peer exclusion and suspension (Bryan, 2017; Cochran, Siennick, & Mears, 2018; Jacobsen, 2019).

Such spuriousness could also apply to an association between suspension and increased involvement with antisocial peers. Youth prefer friendships with peers who share similar characteristics, including behavior problems (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001; Osgood, Feinberg, & Ragan, 2015). It may be that suspended youth become more involved with antisocial peers not because of suspension, but because their own behavior problems make them more compatible with antisocial peers or less so with conforming peers. Therefore, in examining the associations of suspension with changes in friendship preferences and friends’ behavioral composition, the ability to account for a wide range of potential confounders is critical.

LONGITUDINAL NETWORK APPROACH

Examining the exclusionary processes I have described requires the ability to identify (1) which peers consider the respondent to be a friend, separately from (2) which peers the respondent considers to be a friend. Discontinuity in the former should capture rejection (as much as it is associated with suspension), and discontinuity in the latter should capture withdrawal. Therefore, such an examination also requires that this information be longitudinal, tracking the same respondents and a consistent body of their peers over time. Most prior studies of labeling or peer exclusion have relied on respondent perceptions of exclusion or on general peer preferences, rather than changes in specific friendships over time (Dodge et al., 2003; Wiley, Slocum, & Esbensen, 2013). Some of this work has focused on suspension specifically and has been longitudinal. Pyne (2019) found that students at risk of suspension perceived lower belongingness or connectedness to peers but little evidence that suspension is associated with changes in such perceptions. I revisit this by focusing on changes in ties among actors in a network, rather than less specific perceptions. Using nomination data (“name your closest friends”), ties are based on nominations of respondents toward peers (outgoing ties) or of peers toward respondents (incoming ties). This provides a more complete picture of student networks (Young et al., 2011) and allows for operationalizing rejection and withdrawal as within-individual changes in nominations (Schaefer, Kornienko, & Fox, 2011).

STUDY CONTRIBUTIONS

This work extends prior research on the consequences of excessive crime control for social exclusion and inequality (Kirk & Wakefield, 2018) by focusing on school suspension, which many suggest is a precursor to criminal justice involvement (Hirschfield, 2018b; Kupchik 2010; Mittleman 2018; Mowen and Brent 2016; Ramey 2016). Moreover, it advances knowledge of the prevalence and outcomes of suspension in rural schools. It also joins others in shifting the focus dominating prior labeling research from diminished institutional attachment and secondary deviance to the micro-level processes of interpersonal exclusion implied in labeling theories (Bryan, 2017; Cochran et al., 2018; Mowen, 2017; Rengifo & DeWitt, 2019). Additionally, it shows how these network processes may be observed over time (e.g., Schaefer et al., 2011). This is a particularly important contribution in the context of suspension due to the limited availability of individual-level discipline information combined with longitudinal network data.

First, I examine descriptive differences in network size and other characteristics between suspended and non-suspended students. Second, I test the association between suspension and the deterioration of incoming ties (rejection) and outgoing ties (withdrawal) from one wave or grade to the next. Third, I assess the extent to which school absence (an indicator of separation from school friends) explains this association. As a sensitivity check, I compare results using alternative outcome measures based on changes in perceptions of peer exclusion. Finding analyses of perceptions consistent with the main results would be evidence of the reliability of my network approach. Fourth, I assess changes in the self-reported behavioral composition (substance use and delinquency) of sets of friends, comprised separately of incoming and outgoing ties. Finally, I test whether the associations of suspension with interpersonal exclusion and increased involvement with antisocial peers are stronger in smaller schools.

DATA AND METHODS

DATA

Predominantly Rural Sample

Data were collected as part of the test of the PROSPER partnership model, a project for delivering community-focused interventions for reducing adolescent substance use and risky behavior (Spoth et al., 2007). The project included all sixth-grade students in 28 predominantly rural public school districts, with 14 each in Iowa and Pennsylvania (about 11,000 participants at baseline, with 162 to 792 per school district). To be eligible, districts had to have between 1,300 and 5,200 students, with no less than 15% eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.2 These enrollment-specific criteria result in grades being considerably larger on average than they are in rural schools nationally, and even larger than US schools overall (Appendix A). Two successive cohorts of students participated, completing baseline surveys in school during fall of sixth grade (2002 and 2003). They then completed follow-up surveys in spring the same year and every year after to ninth grade (five waves).3 As part of this in-school survey, students were asked to list the names of their two closest friends and up to five other close friends in their same grade and school. Ninety-six percent of participating students provided nomination data for at least one wave. It total, 83% of nominations were matched successfully to class rosters, with an average of four names per student-wave. Unsuccessful matches occurred when nominations were not on the class roster (15%) or there were multiple plausible names (2%).

Suspension data were collected from additional in-home questionnaires administered to a randomly selected subset of students from the 2003 cohort and their parents. Interviewers contacted the families via mail and telephone, followed by an in-person recruitment visit. Of 2,267 families invited, 979 (43%) participated (Lippold, Greenberg, & Collins, 2013). This low participation rate resulted in an in-home subsample that has small but statistically significant differences from the larger PROSPER sample. Compared to students in the larger sample (full 2003 cohort), students in the in-home subsample were more likely to be white. They had more friends in school and were somewhat less likely to report delinquency or substance use; however, they were similar in terms of socioeconomic status (free or reduced-price lunch) and proportion male or female (Appendix A). Students as well as their mothers, and fathers when present (70% at baseline), completed written questionnaires concurrently with the five waves of the larger in-school survey. By ninth grade, 75% of students were still participating, with an average participation of about three waves per student (participation rates in Appendix B).

I limit my analytic sample to 2,915 in-home participant observations in the spring of grades six to nine. This excludes follow-up observations of 140 students who continued participating in the in-home survey but moved away from a PROSPER school district, leaving no basis for assessing rejection and withdrawal. I do not include observations from the fall of sixth grade (baseline) as cases in the analyses because my focus is on discontinuity in friendship ties from the prior to the current grade. However, data from fall of sixth grade contribute because control variables are lagged to the previous wave to establish the appropriate temporal ordering with key variables. Of these 2,915 observations I exclude 378 in which the student did not complete the in-school survey due to refusal, incompletion, or absence (about the same number for each reason). I also drop 164 cases due to nonresponse in the suspension items, resulting in an analytic sample of N=2,373 observations from 766 students. At baseline, there are no notable differences between students in my analytic sample and those of the in-home subsample from which they are drawn, but there are disproportionately fewer racial minorities compared to the full PROSPER 2003 cohort (12% vs. 16%) and to the entire US population of rural, regular public-school sixth-graders in the same year (21%; Appendix A). Forty-one percent of the racial minorities in my sample are Hispanic and 17% are non-Hispanic black. Therefore, results of my analyses may not generalize to all racial minority youth in these school districts.

Variables

Outcome Variables.

Friends are defined by respondent nominations of peers (maximum of seven) or peer nominations of the respondent (could be nominated by anyone in grade). I examine disparities in the number of friendship nominations made and received, but my main outcome of interest is a within-individual discontinuity in or loss of nominations from one grade to the next. I focus on same-grade peers because they provide a consistent pool of potential friends as students advance through middle school and into high school. They are also the most relevant audience likely to learn of and respond to suspension. Peers beyond this pool should be considered as well but are not as easily incorporated in a full network analysis. To provide some perspective beyond same-grade peers, in descriptive analyses I also consider the number of close friends the respondent reports to have in other grades and schools.

Discontinuity in friendship nominations is represented in two ways. Withdrawal represents the number of friendship nominations the respondent made in the previous wave but did not repeat in the current wave. Rejection represents the number of friendship nominations the respondent received in the previous wave but lost (did not receive) again in the current wave.4

In examining whether suspension is associated with increased involvement with antisocial peers, I focus on two behaviors of friends: substance use and delinquency. Both are based on self-reports of peers who participated in the in-school survey and were nominated by the respondent, or nominated the respondent as a friend. Substance use is based on four items about the frequency of smoking, drinking alcohol, getting drunk, and using marijuana in the past month (alpha=0.76). Delinquency is based on responses to 12 items about the frequency of a range of behaviors in the past year (e.g., theft, fighting, vandalism; alpha=0.82). A complete list of items for each measure is provided in Appendix C. To address issues with skewness in combining items, each measure is constructed using the graded response model from item response theory (an extension of the two-parameter logistic model; Samejima, 1969). This transforms each into an equal-interval scale with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 (Osgood, McMorris, & Potenza, 2002). Principle component analyses for each measure supported the assumption in item response theory that there is a single dominant latent variable underlying the respective items. Final measures represent the mean substance use and the mean delinquency across the respondent’s friends. One version of each pertains to peers whom the respondent nominated as a friend, and the other to peers who nominated the respondent.

Explanatory Variable.

Suspension data represent student self-reports on the number of times they were “suspended from school for disciplinary reasons” in the past 12 months. To minimize underreporting, these are combined with responses from up to two participating parents (“In the past year, has this child ever been suspended from school for disciplinary reasons? How many times?”). The number of suspensions is based on the maximum number of times indicated by any of the three potential reporters. For example, if the student reports two suspensions but the mother and father each report only one, I count this as two suspensions. In my analytic sample, 155 families, or 20%, reported that the student experienced at least one suspension between fifth and ninth grade. Of these, a little more than half reported being suspended more than once, and one-third reported being suspended at least three times. Eight percent were suspended ten or more times, or an average of more than twice per grade. For the multivariable analyses, I collapse these suspension counts into a set of three time-varying dummy variables. The first represents the reference category and includes students who were never suspended between the fifth grade and a given subsequent grade. The second refers to students who were suspended once, and the third to students who were suspended more than once. These are time-varying because students in each category at a given wave could report a new suspension at a subsequent wave. This way, the measure is indicative of a label carried across years—one that should become more salient the more times a student is suspended.

This measure is limited because I do not have data on whether the student was suspended prior to the first wave, meaning my analyses assume suspensions in fifth-grade are first-time suspensions. However, this appears to be a safe assumption because few students or parents (4%) reported that the student was suspended in fifth grade, and by sixth grade, the prevalence of suspension (8%) is consistent with cumulative risk between first and sixth grade for rural students nationally (details in results section). The measure is also limited because it does not allow for assessing other differences in suspension (e.g., in-school or out-of-school, duration, etc.) or other forms of exclusionary discipline such as expulsion. Some forms may have more or less impact than others, but unfortunately few large-scale datasets distinguish between types.

School Absence.

Absence, a measure of separation, is based on in-school self-reports on the number of days the student was absent in the past year (1=none, 2=1 to 2 days, 3=3 to 6 days, 4=7 to 15 days, and 5=16 or more days). Data on the length of suspensions or reasons for missing school are not available. I combine the last two categories (only 5% missed 16 or more days) and construct a set of dummy variables with the reference group representing those who never missed 7 or more days in a year by a given wave or any previous wave. The second group includes students who ever missed 7 or more days (not necessarily consecutively), and the third group refers to students who missed this amount more than once since sixth grade. In analyses not shown, I compare results using measures based on other cutoffs (3 or more, 16 or more), but the 7-day cutoff explains a larger portion of the association between suspension and friendship tie discontinuity than the others do. Among students who missed 7 days in a single year, 42% did this in more than one wave. These may be at greater risk of weakened ties among school peers.

Weakened Institutional Attachment.

Two indicators of weakened institutional attachment include low school attachment and low academic achievement. Low school attachment represents the average of five in-home survey items ranging from 1=not at all true to 5=really true. Examples include “I wish I could move to another school,” “I like being in my school” (reverse coded), and “I wish I could stay home from school” (alpha=0.83). For increased reliability, low achievement is based on the combined reports of the student and participating parents about the grades the student usually gets in school, ranging from 1=mostly A’s to 9=mostly F’s. The final measure represents the average across the standardized (z-score) version of each of the individual reports (alpha=0.91).

School Size and Other Control Variables.

As the most relevant aspect of school size, I use the number of students per grade as a control variable and in examining whether associations with friendship discontinuity are stronger in smaller schools. I also address concerns with selection on observed characteristics by including a rich set of controls from both the in-school and in-home surveys (full list in Table 1). Among these are behavioral antecedents to suspension, each measured prior to the current wave (one-wave lags). These include school misbehavior (disrupting class, talking back to teachers, breaking rules, etc.), delinquency, substance use, and risk and sensation seeking. Controlling for antisocial behaviors eases concerns about reverse causality because labeling theories suggest the effects of peer exclusion on suspension (the reverse relationship) would operate through increases in antisocial behavior. Other controls include indicators of economic disadvantage, residential mobility, parenting behaviors, after-school activities, and other reasons for friendship changes such as when friends drop out, move away, or choose not to participate in the survey (coding described in Appendix D). I also control for current wave (grade) to account for trends in behavior and friendship selection. All but four variables are missing less than 10% of observations. These four include parent self-reports of any prior arrest, asked only at ninth grade (21%), the racial composition of friendship nominations made (15%), special education services (11%), and risk and sensation seeking (11%). I use multiple imputation with chained equations to address missing data (analyses rely on 20 imputed datasets) and to preserve a consistent sample size when comparing across nested models. Supplemental analyses not shown used listwise deletion instead of imputation; with this approach, multivariable regression coefficients were very similar in terms of size and direction but models relied on smaller portions of the sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Sixth-Grade Observations

| Variable | Suspended during Study |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never Suspended during Study | Suspended by Sixth Grade | Suspended after Sixth Grade | Full Sample at Sixth Grade | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Friendship Nominations Lost Since Last Wave | |||||||||

| Number of nominations made last wave (0 to 7) | 3.69 | * | 2.57 | 3.44 | 2.62 | 2.83 | 2.41 | 3.58 | 2.57 |

| Mean proportion lost since last wavea (0 to 1) | .33 | * | .27 | .46 | .28 | .36 | .33 | .34 | .28 |

| Number of nominations received last wave (0 to 16) | 3.47 | *** | 2.72 | 2.62 | 2.40 | 2.42 | 2.65 | 3.29 | 2.71 |

| Mean proportion lost since last waveb (0 to 1) | .36 | ** | .32 | .60 | .34 | .38 | .37 | .38 | .33 |

| School Absence (ref: Never Missed 7+ days) | |||||||||

| Missed 7+ days of school in a year since fall of 6th grade | .19 | .40 | .20 | .40 | .22 | .42 | .20 | .40 | |

| Missed 7+ days of school in a year more than once since fall of 6th grade | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Weakened Institutional Attachment | |||||||||

| Low school attachment current wave (1 to 5) | 2.11 | ** | .85 | 2.50 | .83 | 2.31 | .97 | 2.16 | .87 |

| Low academic achievement current wave (z-score) | −.22 | *** | .81 | .35 | .91 | .19 | .95 | −.13 | .86 |

| Control Variables | |||||||||

| Male (ref: Female) | .43 | *** | .50 | .76 | .43 | .57 | .50 | .47 | .50 |

| Nonwhite (ref: Non-Hispanic white) | .10 | ** | .30 | .20 | .40 | .21 | .41 | .12 | .33 |

| Nominations made last wave no longer in school/study (log) | .17 | .34 | .26 | .41 | .20 | .38 | .18 | .35 | |

| Nominations received last wave no longer in school/study (log) | .22 | * | .36 | .11 | .27 | .17 | .35 | .21 | .36 |

| Racial composition of nominations made last wave all white | .69 | * | .46 | .51 | .50 | .63 | .49 | .67 | .47 |

| Racial composition of nominations received last wave all white | .71 | .45 | .62 | .49 | .74 | .44 | .71 | .46 | |

| Number of students in grade last wave (6 to 470) | 167.30 | 105.62 | 177.75 | 126.84 | 163.63 | 99.76 | 167.75 | 106.75 | |

| Transitioned to new school last wave | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Miles to school last wave (log) | 1.23 | .62 | 1.18 | .59 | 1.12 | .54 | 1.22 | .61 | |

| Special education services last wave | .17 | *** | .38 | .44 | .50 | .26 | .44 | .20 | .40 |

| Structured activities after school last wave (z-score) | −.09 | 1.02 | −.08 | .85 | −.29 | .78 | −.11 | .98 | |

| Unstructured socializing after school last wave (z-score) | −.12 | *** | .97 | .26 | 1.10 | .22 | 1.17 | −.06 | 1.01 |

| Any substance use last wave | .05 | ** | .21 | .13 | .34 | .11 | .32 | .06 | .68 |

| Delinquency variety score last wave (log) | .25 | *** | .45 | .73 | .67 | .44 | .60 | .31 | .51 |

| Frequency of school misbehavior last wave (log) | .27 | *** | .25 | .67 | .33 | .51 | .33 | .33 | .30 |

| Risk and sensation seeking last wave (1 to 5) | 1.82 | *** | .82 | 2.29 | .95 | 2.05 | .98 | 1.88 | .86 |

| Frequency of bully victimization last wave (log) | .27 | *** | .30 | .38 | .36 | .40 | .38 | .29 | .32 |

| Parental discipline last wave (1 to 5) | 3.73 | *** | .89 | 3.20 | 1.12 | 3.52 | .94 | 3.66 | .92 |

| Parental monitoring last wave (1 to 5) | 4.61 | *** | .51 | 4.28 | .65 | 4.48 | .51 | 4.57 | .53 |

| Parent education last wave (z-score) | −.01 | *** | 1.02 | −.28 | 1.15 | −.47 | .79 | −.07 | 1.02 |

| Household income last wave (log) | 10.78 | *** | .79 | 10.42 | .86 | 10.32 | .86 | 10.70 | .82 |

| Parent unemployment last wave | .11 | *** | .31 | .16 | .37 | .28 | .45 | .13 | .34 |

| Parent ever arrested (ninth grade only) | .14 | *** | .35 | .42 | .50 | .29 | .46 | .18 | .38 |

| Mother relationship transitions last wave (0 to 8) | 1.97 | 1.45 | 2.24 | 1.71 | 2.17 | 1.39 | 2.01 | 1.46 | |

| Children in household last wave (0 to 8) | 2.45 | 1.03 | 2.75 | 1.32 | 2.31 | .91 | 2.46 | 1.05 | |

| Mother depression last wave | .23 | *** | .42 | .40 | .49 | .40 | .49 | .26 | .44 |

| Religiosity last wave (1 to 6) | 3.98 | *** | 1.77 | 3.53 | 1.73 | 3.22 | 1.81 | 3.86 | 1.78 |

| Years in current residence last wave (0 to 19) | 6.40 | *** | 4.08 | 5.16 | 3.93 | 4.93 | 3.69 | 6.15 | 4.06 |

| Community cohesion last wave (z-score) | −.01 | ** | 1.03 | .17 | 1.09 | .39 | 1.04 | .05 | 1.04 |

| N of Students (Unweighted) | 561 | 55 | 72 | 688 | |||||

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to 2,373 observations of 766 in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, valid data on suspension. Only sixth-grade observations are shown here (n=688). Control variable for current grade not shown. Results based on first of 20 multiply imputed datasets. Independent samples t-tests compare ever-suspended students (those in either of the middle two categories) to never-suspended students.

Of those who made nominations last wave (n=444 non-suspended, 42 suspended by sixth, 53 suspended after sixth, 539 total)

Of those who received nominations last wave (n=500 non-suspended, 44 suspended by sixth, 57 suspended after sixth, 601 total)

ABBREVIATIONS: M = mean; SD = standard deviation

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05 (two-tailed)

Analytic Strategy

After examining descriptive statistics by suspension, analyses proceed in the order of my three main hypotheses: (1) interpersonal exclusion, (2) increased involvement with antisocial peers, and (3) stronger associations in smaller rural schools.

Interpersonal Exclusion.

To estimate the risk of losing a specific friend, I rely on generalized estimating equations (Liang & Zeger, 1986), an extension of generalized linear models that provides a semiparametric approach to analyses of panel data with a categorical outcome. I use a logit link function and binomial probability distribution to estimate differences in the odds of losing a friend from one wave to the next. This is similar to a random-effects logistic regression approach, but it estimates a population-averaged effect rather than the effect of a change in suspension status. A key benefit of this strategy for network analysis is that using the binomial probability allows me to account for variation in the number of possible friends to lose across students and waves (the “trials” for this application of the binomial). Analyses estimate the odds of discontinuity in nominations among suspended students compared to their non-suspended counterparts. I test the overall association with friendship discontinuity and then estimate the proportion of that association explained by lengthy or repeated school absence.

After accounting for school absence, a remaining association may be due to rejection or withdrawal but could also be due to unobserved heterogeneity. My focus on discontinuity in friendship ties, a type of within-individual change, should partially address this concern. To address it even further, I respecify my models among students with high levels of school misbehavior, delinquency, or substance use (above median in grade). Next, I check the robustness of my results to alternative measures of peer exclusion based on perceptions, rather than network data. For greater reliability, I use both student self-reports and parent perceptions of the student’s exclusion from school peers. I analyze these outcomes with within-individual, fixed-effects models (Allison, 2009).5 An important benefit of this approach is that it adjusts for all observed and unobserved time-stable differences between suspended and non-suspended students. A limitation is that it is still subject to bias due to unobserved time-varying characteristics and does not provide between-person estimates.

Increased Involvement with Antisocial Peers.

In examining associations between suspension and changes in network behavioral composition, I focus on friends’ past-month substance use and past-year delinquency. I observe changes in the mean levels of substance use and delinquency across peers the respondent nominated as a friend and across those who nominated the respondent. Analyses again use individual fixed-effects and include all time-varying control variables to minimize concerns with unobserved heterogeneity and selection.

Stronger Associations in Smaller Rural Schools.

To examine heterogeneity by school size in these proposed associations, I test for an interaction between suspension and the number of students in the respondent’s grade. I first test for heterogeneity in the association of suspension with friendship discontinuity and then in the association with behavioral composition of student friendship networks. A summary of results (presented as fitted probabilities) is graphed for ease of interpretation.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS BY SUSPENSION STATUS

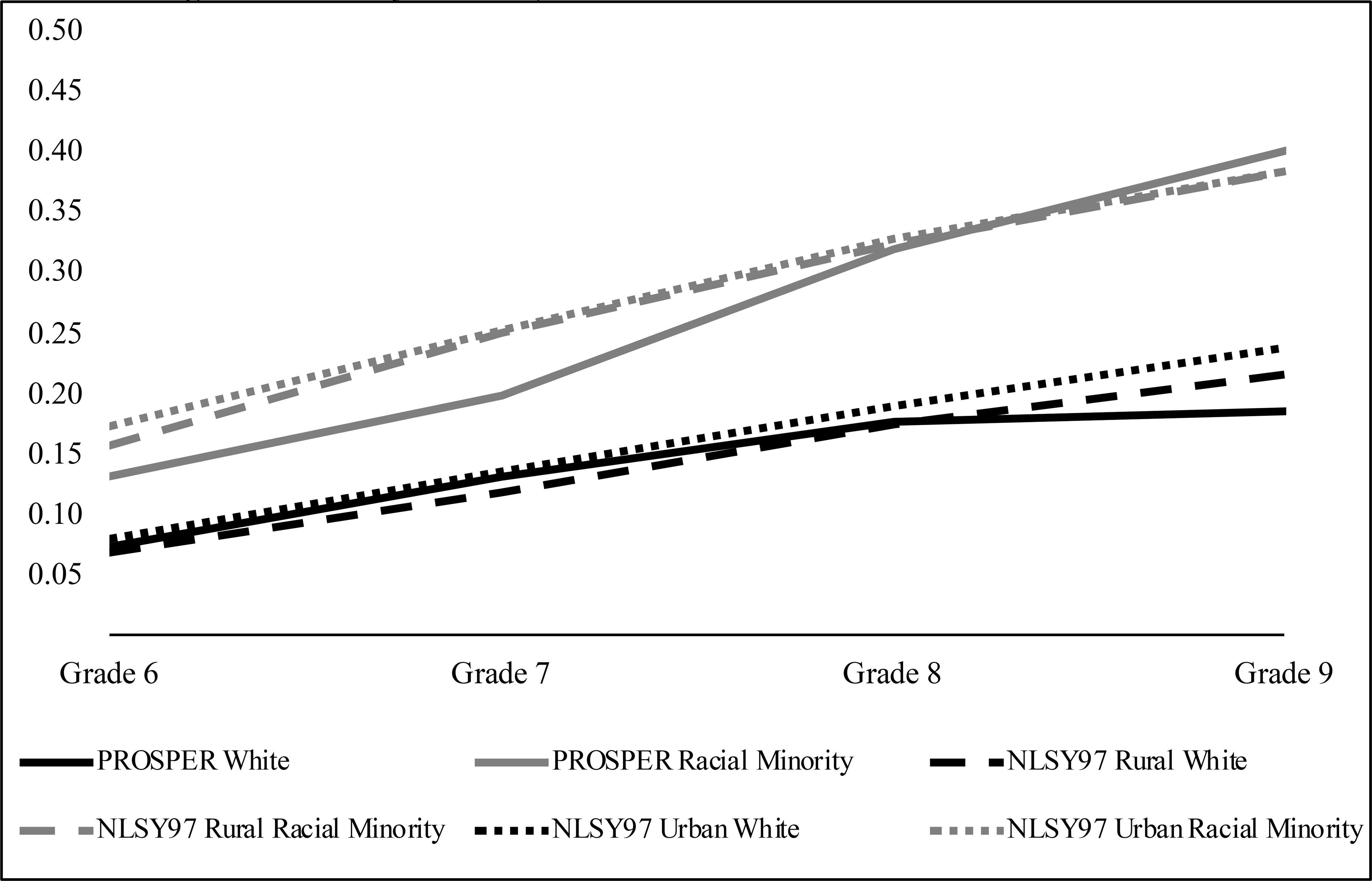

Figure 1 illustrates how risk of experiencing a suspension accumulates in my sample as students advance from sixth to ninth grade. For reference, I compare these to a nationally representative sample of rural and urban students in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97). I combine racial minorities (Hispanic or nonwhite) as a single category because there are so few in rural areas relative to non-Hispanic whites (12% in my sample vs. 17% of rural youth in the NLSY97). Little is known about the prevalence of suspension among rural youth. My results suggest cumulative risk is about as high in rural areas as it is in urban areas, particularly after seventh grade. Also striking is the consistency across samples of the difference between whites and racial minorities. Nearly 15% of racial minority youth have already been suspended from school by sixth grade, compared to just over 5% of whites. By about the time they transition into high school, 40% of racial minorities have been suspended, compared to fewer than 20% of whites.

Figure 1. Cumulative Risk of Suspension for Whites and Racial Minorities in PROSPER and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 Cohort.

NOTES: PROSPER N=766 students (unweighted) with some variation across waves. NLSY97 N=8,984 youth, but 380 excluded due to unknown urban/rural status. Grades 6, 7, 8, and 9 in PROSPER correspond to ages 12, 13, 14, and 15 in the NLSY97. NLSY97 data are weighted to represent adolescents at each age nationally. Urban/rural defined by Census, based on respondent’s 1997 residence. PROSPER includes disproportionately more Hispanics and fewer blacks than NLSY97.

Descriptive statistics in Table 1 compare suspended students with their non-suspended counterparts. Means and standard deviations are presented for the full sample and by three categories of suspension: never suspended during study, suspended by sixth grade, and suspended after sixth grade. Independent samples t-tests compare means between (1) non-suspended students and (2) students in either of the latter two subgroups of students suspended during the study. Splitting the sample this way reveals important correlates of suspension. Students who get suspended (especially if suspended in sixth grade) come from more disadvantaged backgrounds than those who never experience suspension during the study. They are more likely to have experienced stressful life circumstances such as residential mobility, parental unemployment, and maternal depression than students who do not experience suspension. Their parents are also more likely to have experienced criminal justice contact. Perhaps due in part to these family conditions, they exhibit more misbehavior in school and lower levels of achievement. In addition, their parents monitor and discipline their child’s behavior with less consistency, providing more opportunities for unstructured socializing and greater involvement in substance use, delinquency, and other risky behaviors (see Appendix E for more summary statistics, including between- and within-person standard deviations).

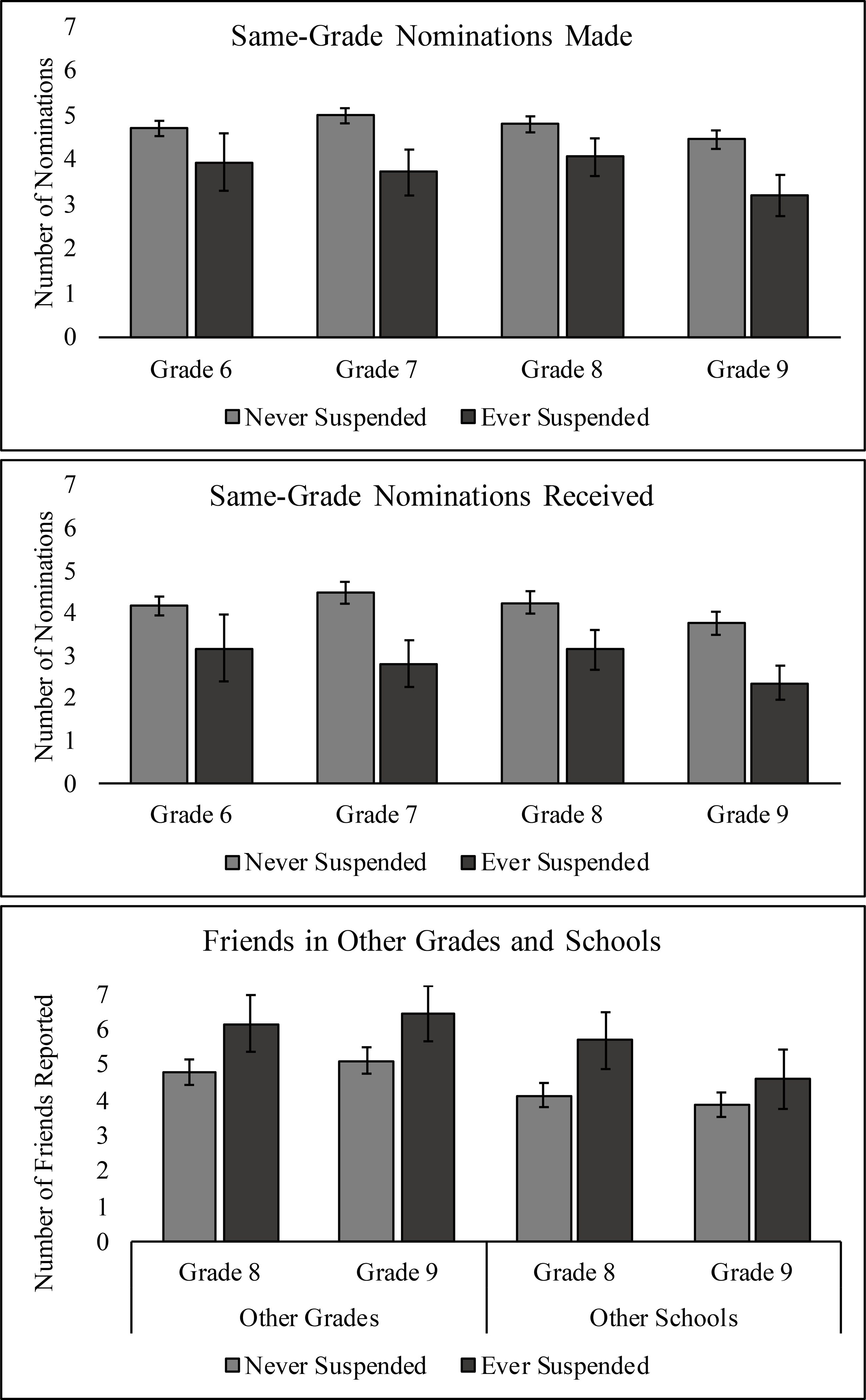

I now examine how suspended students differ from their peers in the size of their friendship networks. Figure 2 presents the average number of friends for students who were suspended by a given wave relative to those who were not. In sixth grade, suspended students nominate four peers in their grades as close friends and receive about three nominations. This is about one nomination less than non-suspended students make or receive. By ninth grade, this difference approaches two friends, partly due to a greater decline in same-grade friends among suspended students. Whereas non-suspended students still nominate a little less than five peers as friends and receive nominations from four, students who have been suspended make only three nominations and receive just over two. Some of this difference may be due to suspension, but some may also be due to more disadvantaged students already having fewer friends. Indeed, students with lower household incomes (below median) make and receive fewer nominations than those with higher incomes (3 made and 3 received versus 4 made and 4 received), and racial minorities make and receive fewer nominations than whites (3 made and 3 received versus 4 made and just over 3 received). If suspension is associated with interpersonal exclusion, even if the overall association is not large, it may be especially meaningful for students who already have fewer same-grade friends. It may also provide opportunities for shared experiences with youth in other grades during in-school suspension or youth outside school during out-of-school suspension. Indeed, the bottom panel of Figure 2 suggests that, compared to other students by the end of middle school, suspended youth have more friends in other grades (6 compared to 5) and other schools (6 compared to 4). Supplemental analyses also suggest a greater proportion of their friends are older than they are, as perceived by parents.6

Figure 2. Network Size by Suspension Status, Grades 6 to 9.

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to observations of in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, and valid data on suspension. N=2,373 observations from 766 students. Data on friends in other grades and schools are only available in later waves (n=1,059).

INTERPERSONAL EXCLUSION

Suspended students have fewer friends in their grade than their peers, but assessing the extent to which they are excluded from particular peers requires moving beyond the basic question of network size to examine discontinuity in specific friendships over time. Table 2 presents multivariable results for discontinuity in same-grade nominations that the respondent makes and then for discontinuity in nominations the respondent receives (full models with controls are presented in Appendix F). Because these analyses exclude observations in which students did not make or receive nominations respectively in the preceding wave, the number of students varies from the full sample of 766 (down to n=697 for analyses of nominations made and n=734 for analyses of nominations received). The first column on the left presents models that include suspension variables without controls. Moving right, the second column shows models that include control variables, and the third column adds controls for weakened institutional attachment. The fourth column adds variables that capture school absence. Finally, in the fifth column, I repeat the analyses presented in the fourth column after limiting the sample to observations with the highest levels of antisocial behavior.

Table 2.

Binomial Generalized Estimating Equations: Log Odds of Losing a Friendship Nomination Associated with Suspension

| Model | Suspension | Add Control Variables | Add Weakened Institutional Attachment | Add School Absence | High Antisocial Observations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Panel A: Friendship Nomination Made | |||||||||||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | |||||||||||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .27 | ** | (.09) | .20 | * | (.09) | .19 | * | (.09) | .18 | (.09) | .24 | * | (.11) | |

| Suspended more than once by current wave | .39 | *** | (.09) | .25 | * | (.11) | .25 | * | (.11) | .22 | * | (.11) | .29 | * | (.11) |

| Weakened institutional attachment | |||||||||||||||

| Low school attachment current wave | .06 | * | (.03) | .06 | * | (.03) | .01 | (.04) | |||||||

| Low academic achievement current wave | .03 | (.03) | .02 | (.03) | .03 | (.04) | |||||||||

| School Absence (ref: Never missed 7+ days in study) | |||||||||||||||

| Missed 7+ days of school in a year by current wave | .04 | (.07) | −.01 | (.09) | |||||||||||

| Missed 7+ days of school more than once by current wave | .24 | ** | (.07) | .23 | * | (.09) | |||||||||

| Observations | 2,022 | 2,022 | 2,022 | 2,022 | 1,110 | ||||||||||

| Students | 697 | 697 | 697 | 697 | 497 | ||||||||||

| Panel B: Friendship Nomination Received | |||||||||||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | |||||||||||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .25 | ** | (.09) | .09 | (.10) | .09 | (.10) | .09 | (.10) | .13 | (.12) | ||||

| Suspended more than once by current wave | .46 | *** | (.10) | .25 | * | (.11) | .23 | * | (.11) | .21 | (.11) | .24 | (.13) | ||

| Weakened institutional attachment | |||||||||||||||

| Low school attachment current wave | −.03 | (.03) | −.03 | (.03) | −.07 | (.05) | |||||||||

| Low academic achievement current wave | .02 | (.03) | .01 | (.03) | .04 | (.04) | |||||||||

| School Absence (ref: Never missed 7+ days in study) | |||||||||||||||

| Missed 7+ days of school in a year by current wave | .06 | (.07) | .08 | (.09) | |||||||||||

| Missed 7+ days of school more than once by current wave | .15 | (.08) | .02 | (.10) | |||||||||||

| Observations | 2,154 | 2,154 | 2,154 | 2,154 | 1,044 | ||||||||||

| Students | 734 | 734 | 734 | 734 | 483 | ||||||||||

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to observations of in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, valid data on suspension. Models of nominations made exclude 351 observations of students who did not make a nomination last wave. Models of nominations received exclude 219 observations of students who did not receive a nomination last wave. Suspension and absences observed beginning fall of sixth grade. Control variables are not shown for brevity. High antisocial observations have higher than median substance use, delinquency, or school misbehavior. Results combined across 20 multiply imputed datasets.

ABBREVIATIONS: b = log odds coefficient; SE = standard error; ref = reference category

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05 (two-tailed)

I begin at Panel A by examining the likelihood of discontinuing a same-grade friendship nomination made in the previous wave. Results suggest that among students who have been suspended, the odds of discontinuing a nomination are 31% greater [(e0.27 – 1) ∙ 100] than the odds among non-suspended students (p<.01). This association is stronger for students who have experienced multiple suspensions. Among these, the odds of discontinuing a nomination are 47% greater than the odds among non-suspended students (p<.001). When control variables are added, the associations for both groups remain positive and statistically significant. Among students with one suspension, the odds of discontinuing a nomination are 22% greater than the odds for non-suspended students, and among those with multiple suspensions, the odds are 29% greater. I also add controls for low school attachment and achievement to assess whether they explain these results. Their associations with the outcome are weak, and statistically significant only for low school attachment. One unit of low attachment is associated with a 7% greater odds [(e0.06 – 1) ∙ 100] of discontinuing a nomination (p<.05). Accounting for these variables reduces the coefficient for one suspension by only 4% and does not affect the coefficient for multiple suspensions. 7 After adjusting for all of these controls, converting the log odds coefficients for suspension to fitted probabilities reveals an increase of 0.05 (from 0.42 to 0.47) in the probability of discontinuing a nomination made for students with one suspension, and a difference of 0.06 for multiple suspensions.

Next, I add school absence to the model (due to missing school), and the coefficients for suspension decline further, by 5% for students with one suspension and 13% among students with multiple suspensions. Students who missed 7 or more days in a year are no more likely to discontinue a nomination from the previous wave than those who never had this degree of lengthy or repeated absence during the study. However, among students who have accumulated such absences across multiple waves, the odds of discontinuing a nomination are 27% greater [(e0.24 – 1) ∙ 100] than the odds for the reference category (p<.01). Finally, I respecify these models after retaining only cases with above-median antisocial behaviors in the preceding wave (n=1,110). If results to this point have been biased by unobserved heterogeneity, I would expect the association to decrease substantially. However, the final column of Table 2 suggests the opposite—effect sizes increase slightly and remain statistically significant.

I now move to Panel B of Table 2 to examine the association between suspension and the respondent’s likelihood of losing a friendship nomination received in the previous wave. Without accounting for controls, the odds of suspended students losing a nomination are 29% greater [(e0.25 – 1) ∙ 100] than the odds among non-suspended students (p<.01). This association is larger for students with multiple suspensions: 58% greater than the odds among non-suspended students (p<.001). When controls are added, the coefficients decline substantially (by 63% for students suspended once, 46% for students suspended more than once), suggesting much of this association was driven by selection on observed characteristics. The log-odds coefficient for students suspended only once approaches zero, but the coefficient for those carrying multiple suspensions remains positive and statistically significant. Among these students, the odds of losing a nomination are 29% greater than the odds among non-suspended students (p<.05). I also add controls for low school attachment and achievement, this time focusing on associations for students with multiple suspensions, because associations for students suspended only once were not statistically significant in the previous model. Neither low attachment nor low achievement is significantly associated with discontinuity in nominations received, and these variables reduce the size of the coefficient for multiple suspension by only 5%. After adjusting for all of these controls, converting the log odds for multiple suspensions to a fitted probability reveals an increase of 0.06 (from 0.47 to 0.53) in the probability of discontinuing a nomination received in the previous wave.

Next, I add school absence to the model and again find that it explains only a small part (9%) of the association between suspension and the odds of losing a friendship nomination. For students who have accumulated lengthy or repeated absences over multiple waves, the odds of losing a nomination are 16% greater [(e0.15 – 1) ∙ 100] than the odds among students who never missed 7 or more days in a year (p<.10). Adding school absence to the model causes the coefficient for multiple suspensions to decline below statistical significance but remain stable in size (b=0.21; p<.10). I also check the robustness of these models by limiting the analytic sample to observations with above-median antisocial behaviors (n=1,044). Again, the log-odds coefficient for students with multiple suspensions remains stable (b=0.24; p=<.10). In supplemental models not shown,8 I explore variation in these results by racial minority status and gender. I find no significant differences for boys relative to girls or for racial minorities relative to whites in associations with discontinuity in friendship nominations made or received.9

Alternative Measures of Peer Exclusion

I now examine the robustness of my results to three alternative measures based on perceptions of exclusion from friends at school rather than nomination change: loneliness at school, poor relationships with school friends, and parent-perceived rejection by school friends. Loneliness at school represents the mean of three items adapted from the Children’s Loneliness Scale (Asher & Wheeler, 1985), each ranging from 1=not at all true to 5=really true. Examples include “I feel left out of things at school” and “I feel lonely at school” (alpha=0.93). Poor relationships with school friends also represents the mean of three items, each asking about relationships in the past year (1=never true to 5=always true). Examples include “My school friends and I got along well” (reverse coded)” and “I had a hard time making friends at school” (alpha=0.66). Parent-perceived rejection by school friends is constructed from two items asking parents what percentage of their child’s school friends (1) like and accept him or her (reverse coded) and (2) dislike and reject him or her. Responses range from 1=very few (less than 25%) to 5=almost all (more than 75%). Responses are averaged across both items and across reports of both parents (alpha=0.77). To ease concerns about selection, I focus on within-individual change by relying on fixed-effects linear regression models. I also include the same long list of time-varying controls included in my earlier analyses.

Table 3 presents results first without controls and then with their addition. Results reveal no statistically significant associations between suspension and loneliness at school (Panel A) but moderately-sized positive associations with poor relationships with school friends (Panel B) and with parent-perceived rejection (Panel C). Students suspended once have poorer relationships with school friends (b=0.22; p<.05) and higher levels of parent-reported exclusion from school friends (b=0.22; p<.01) after their suspension than they did before. Furthermore, associations are larger with multiple suspensions (b=0.28, p<.05 and b=0.27, p<.01, respectively).

Table 3.

Results of Within-Individual, Fixed-Effects Linear Regression Models: Changes in Three Measures of Perceptions of Peer Exclusion Associated with Suspension

| Model | Suspension | Add Control Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Panel A: Student-Perceived Loneliness at School | ||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | ||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .04 | (.13) | −.05 | (.12) | ||

| Suspended more than once by current wave | .12 | (.14) | .03 | (.14) | ||

| Panel B: Student-Perceived Poor Relationships with School Friends | ||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | ||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .26 | ** | (.09) | .22 | * | (.09) |

| Suspended more than once by current wave | .36 | ** | (.13) | .28 | * | (.13) |

| Panel C: Parent-Perceived Rejection by School Friends | ||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | ||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .22 | ** | (.07) | .22 | ** | (.09) |

| Suspended more than once by current wave | .30 | ** | (.09) | .27 | ** | (.09) |

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to observations of in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, valid data on suspension. N = 2,373 observations from 766 students. Suspension observed beginning fall of sixth grade. Results for controls are omitted for brevity. Each outcome variable is measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Results are combined across 20 multiply imputed datasets.

ABBREVIATIONS: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = robust standard error; ref = reference

p<.01

p<.05 (two-tailed)

INCREASED INVOLVEMENT WITH ANTISOCIAL PEERS

To extend these analyses of friendship discontinuity, I test for changes in network behavioral composition. I again rely on within-individual change following suspension to account for time-stable differences between suspended students and their non-suspended counterparts. Fixed-effects models are presented in Table 4. Coefficients represent the expected standard-deviation unit change in the mean level of substance use or delinquency among friends following the respondent’s suspension. Results in Panel A suggest one suspension is associated with almost one standard-deviation unit increase in substance use among peers the respondent nominates (b=0.92; p<.001) and just under half a standard-deviation unit increase in their delinquency (b=0.43; p<.01). However, when time-varying controls are added, these coefficients are reduced by more than 60%, remaining statistically significant for substance use (b=0.37; p<.05) but not delinquency. Results for multiple suspensions are larger for substance use (b=1.69; p<.001) and delinquency (b=0.90; p<.01), but only changes in the former are robust to time-varying controls. Following multiple suspensions, students experience an increase of more than two-thirds a standard-deviation in substance use among peers they nominate as friends (b=0.69; p<.01).

Table 4.

Results of Within-Individual, Fixed-Effects Linear Regression Models: Standard Deviation-Unit Change in the Mean-Level of Friends’ Substance Use and Delinquency Associated with Suspension

| Model | Mean Past-Month Substance Use of Friends | Mean Past-Year Delinquency of Friends | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Suspension | Add Control Variables | Suspension | Add Control Variables | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Panel A: Friendship Nominations Made | |||||||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | |||||||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .92 | *** | (.18) | .37 | * | (.18) | .43 | ** | (.16) | .15 | (.17) |

| Suspended more than once by current wave | 1.69 | *** | (.18) | .69 | ** | (.25) | .90 | ** | (.26) | .35 | (.26) |

| Observations | 2,237 | 2,237 | 2,237 | 2,237 | |||||||

| Students | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | |||||||

| Panel B: Friendship Nominations Received | |||||||||||

| School suspension (ref: Never suspended in study) | |||||||||||

| Suspended by current wave | .74 | *** | (.16) | .22 | (.16) | .25 | (.17) | −.05 | (.17) | ||

| Suspended more than once by current wave | 1.18 | *** | (.24) | .34 | (.23) | .60 | * | (.27) | .00 | (.27) | |

| Observations | 2,175 | 2,175 | 2,175 | 2,175 | |||||||

| Students | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | |||||||

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to observations of in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, valid data on suspension. Models of nominations made exclude 351 observations of students who did not make a nomination last wave. Models of nominations received exclude 219 cases of students who did not receive a nomination last wave. Suspension observed beginning fall, sixth grade. Controls not shown for brevity. Results combined across 20 multiply imputed datasets.

ABBREVIATIONS: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = robust standard error; ref = reference category

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05 (two-tailed)

Results for behavior among peers who nominate the respondent are weaker for levels of substance use and delinquency (Panel B). There is a positive and statistically significant association with substance use (b=0.74, p<.001) that is larger with multiple suspensions (b=1.18, p<.001) but each of these falls below statistical significance when controls are added. There is a smaller positive association with delinquency, but it only reaches statistical significance after multiple suspensions (b=0.60; p<001) and is rendered null with the addition of controls.

STRONGER ASSOCIATIONS AMONG STUDENTS IN SMALLER RURAL SCHOOLS

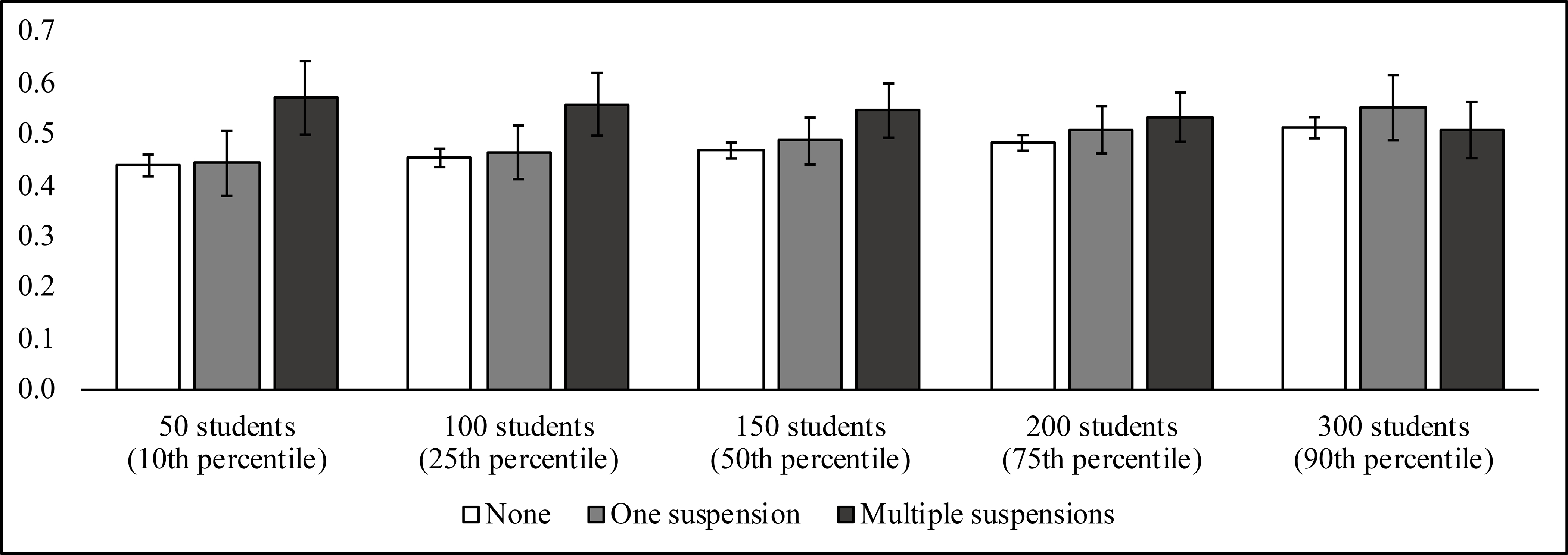

In the final stage of my analyses, I test whether associations reported in Tables 2 and 4 are stronger among students in smaller schools. These earlier results (full models in Appendix F) suggested grade size was associated with greater friendship discontinuity, but associations were quite weak; an increase of 10 students was associated with only a 1% increase [(e0.001 – 1) ∙ 100] in the odds of losing a nomination (p<.001). When the interaction terms described previously are added to these full models, results reveal no statistically significant interactions between grade size and suspension in models of discontinuity in nominations made. Additionally, I find no significant interaction in models of nominations received, if students have only been suspended once. However, the interaction term for students with multiple suspensions is statistically significant (p<.01). Figure 3 summarizes these results with a series of fitted probabilities, shown for respondents with grade sizes of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 students. These grade sizes correspond roughly to the tenth, twenty-fifth, fiftieth, seventy-fifth, and ninetieth percentiles of the sample. Results suggest that for students attending a grade of only 50 students, the probability of losing a friendship nomination received last year is expected to be 0.13 higher following multiple suspensions than it is for students who have not reported a suspension (0.57 compared to 0.44). This difference declines to 0.07 among students with the median grade size (0.54 for multiple suspensions, 0.47 for no suspension) but remains statistically significant. However, among students in the largest grades, those with multiple suspensions appear similar to other youth in their probability of losing a friendship nomination.

Figure 3. Fitted Probablities of Losing a Friendship Nomination Received in Previous Wave, by Grade Size.

NOTES: PROSPER sample limited to observations of in-home survey participants meeting the following criteria: attending participating school district, participated in the in-school survey, and valid data on suspension (N=2,373 observations of 766 students). Results of binomial generalized estimating equation model with controls. The model excludes 219 observations that did not receive a nomination last year. Results are combined across 20 multiply imputed datasets. Percentiles are approximate.

I also check for interactions with grade size in associations with network behavioral composition. I focus on substance use of peers nominated by the respondent because it was the only statistically significant association after accounting for controls. Results reveal no significant variation by grade cohort size in associations with friends’ substance use.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this paper, I have tested key propositions of labeling theories that move beyond a focus on weakened institutional attachment or secondary deviance (Paternoster & Iovanni, 1989) to examine interpersonal exclusion. Using a sample of predominantly rural students and their same-grade peers, I have assessed: (1) the association between suspension and exclusion from school friends, or discontinuity in friendship nominations from one wave to the next, (2) the association between suspension and increased involvement with antisocial peers, and (3) the extent to which these associations are stronger for students in smaller versus larger rural schools.

INTERPERSONAL EXCLUSION

Overall Findings

In regards to interpersonal exclusion, I find that students who have been suspended experience greater discontinuity in friendship with same-grade peers, based on changes in their own preferences and, for those suspended multiple times, changes in the preferences of their peers. These results are robust to a long list of controls for the student’s antisocial behaviors and other factors that might alter friendship preferences; they also hold up among the most antisocial youth in the sample. The likelihood of a friendship tie discontinuing is greater among suspended students than non-suspended students, and this association is larger for students have been suspended more than once. Furthermore, this association does not appear to be driven by weakened institutional attachment, or student disengagement from school following suspension. Moreover, these results are consistent with models of perceived exclusion, in the form of poor relationships with school friends (student-perceived), and rejection (parent-perceived). The one exception was student-perceived loneliness at school, which does not appear to increase following suspension. This null finding seems consistent with prior research on the association between suspension and feelings of connectedness (Pyne, 2019). It may be that as suspended students lose ties to former friends, they replace them with peers in other grades or schools, perhaps including with other suspended peers. Indeed, suspended youth in eighth and ninth grades report having more friends in other grades and schools than their non-suspended peers. This could explain why suspension is not associated with increases in loneliness, even though it is associated with friendship discontinuity and increased discordance with school friends.

Taken together, the associations with network-based measures are not particularly large but they may be harmful, especially for racial minorities and the poor who already have smaller social networks in these rural schools. I find no significant variation in these results by race or gender, but minority girls and boys are much more likely to be suspended and are thus at greater risk of experiencing the deterioration of a friendship tie. Overall, these findings support labeling theories which suggest formal sanctions may weaken or disrupt ties to non-stigmatized or conforming others (Goffman, 1963; Lemert, 1967) and that multiple sanctions may exacerbate already existing disadvantages (Sampson & Laub, 1997).

Rejection, Withdrawal, and Separation from Friends

Additionally, I find that lengthy or repeated school absences explain a small part (5% to 13%) of the association between suspension and friendship discontinuity. The likelihood of discontinuing a nomination made in the previous wave, and the likelihood of losing a nomination received in the previous wave, are greater for students with multiple periods of lengthy or repeated absence than they are for students who had no such absence. Suspension involves temporarily removing a student from school activities and interactions. Therefore, suspensions that are long or repeated likely limit shared experiences among friends in school and weaken their relationships. These findings suggest separation plays much less of a role in the deterioration of interpersonal ties during suspension than it does during formal sanctions of much greater magnitude, such incarceration (Massoglia et al., 2011; see also Rengifo & DeWitt, 2019).