Capsule Summary

Most cases of allergic rhinitis are not diagnosed in Puerto Rican children. We propose a simple approach to AR that would increase the diagnostic accuracy for primary care providers serving populations with limited access to subspecialists.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Puerto Ricans, childhood

To the Editor:

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common asthma comorbidity1, and untreated rhinitis is often a contributory factor to asthma morbidity2. AR can significantly affect the quality of life for affected children3. Although Puerto Rican (PR) children are disproportionately affected by asthma4, access to specialized care is limited. PR allergists currently provide <4% of asthma care5. We hypothesized that AR may be underdiagnosed in PR children, and that identifying major risk factors would allow us to devise a diagnostic approach that could easily be employed by primary care providers in underserved areas.

Children aged 6 to 14 years in San Juan (Puerto Rico) were chosen from randomly selected households using a multistage probability sample design, resulting in 678 children. Only those with non-missing data on allergy skin testing (n=547) were included. Study protocol included questionnaires, allergy skin testing, and blood sample collection. Written parental consent and assent from participating children were obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Puerto Rico (San Jan, Puerto Rico), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts), and University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania).

AR was defined by 1) rhinitis symptoms (in the last 12 months) apart from colds, and 2) skin test reactivity (STR) to ≥1 allergen, consistent with Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 guidelines6 (henceforth referred to as STR-positive AR). Physician-diagnosed AR (PD-AR) was defined by 1) rhinitis symptoms (as above), and 2) physician’s diagnosis (see Methods section in the Online Repository).

A comparison of the characteristics of participants who were (n=547) and were not (n=131) included is shown in Table E1 in the Online Repository. The characteristics of participants who did and did not have STR-positive AR is shown in Table E2 in the Online Repository. Asthma was present in 288 (52.7%) participants. STR-positive AR was present in 192 (66.7%) and 73 (28.2%) children with and without asthma, respectively. Variables significantly associated with STR-positive AR included having symptoms triggered by house dust, pollen, mold and cat; history of an eczematous rash; serum total IgE level; having positive IgE to dust mite or cockroach; and STR to: dust mite, B. tropicalis, cockroach, Alternaria, mouse, mixed trees, Mugwort sage and ragweed. Parental history of AR was significantly associated with STR-positive AR only in children without asthma.

Results of the unadjusted and adjusted analysis of STR-positive AR are shown in Table E3 in the Online Repository. After adjustment for age and sex (Table E3A), private/employer-based health insurance, symptoms triggered by house dust, eczematous rash, and either total IgE level or positive IgE to dust mite were significantly associated with increased odds of STR-positive AR in children with asthma. Asthmatic children who shared their bedroom had reduced odds of STR-positive AR. In the multivariate analysis in non-asthmatics (Table E3B), having symptoms triggered by house dust, having symptoms triggered by pollen, and positive IgE to dust mite were significantly associated with STR-positive AR.

Compared to STR-positive AR, PD-AR was reported in lower proportions of children with (49 or 17.0%) and without (11 or 4.3%) asthma, respectively. Physicians diagnosed AR correctly in only 44 (15.3%) and 9 (3.5%) of the children with and without asthma, respectively. Table E4 in the Online Repository shows the multivariate analysis of PD-AR. Having private/employer-based health insurance, parental history of AR, dog at home, symptoms triggered by cat, and positive IgE to D. Pteronyssinus were significantly associated with increased odds of PD-AR in asthmatic children. In non-asthmatics, parental history of AR and having symptoms triggered by pollen were significantly associated with PD-AR.

Table I shows the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC) of various predictive models for STR-positive AR. PD-AR (Model A) had excellent specificity and PPV but poor sensitivity. Rhinitis symptoms (Model B) had 100% sensitivity (by definition) and acceptable PPV, but reduced specificity, particularly in asthmatics. By adding positive dust mite-IgE (Model C), specificity and PPV were improved, though sensitivity decreased, particularly in children without asthma. A combination of rhinitis symptoms, positive IgE to dust mite, and having symptoms triggered by house dust (Model E) markedly increased sensitivity (88.6–96.8%), while maintaining a high PPV (75.6–80.7%). Substituting total IgE ≥100 kU/L for positive dust mite-IgE (Model G) yielded similar results (and AUC).

TABLE I.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV)* and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve (AUC) for Physician-Diagnosed AR and Various Predictive Models.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | AUC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician-Diagnosed AR – Model A | |||||

| Asthma | 22.9% | 94.8% | 89.8% | 38.1% | 0.59 (0.55–0.63) |

| No Asthma | 12.3% | 98.9% | 81.8% | 74.2% | 0.56 (0.52–0.59) |

| All | 20.0% | 97.5% | 88.3% | 56.5% | 0.59 (0.56–0.61) |

| Rhinitis Symptoms Only – Model B | |||||

| Asthma | 100.0% | 54.2% | 81.4% | 100.0% | ** |

| No Asthma | 100.0% | 86.6% | 74.5% | 100.0% | ** |

| All | 100.0% | 75.5% | 79.3% | 100.0% | ** |

| Rhinitis Symptoms and Dust Mite-IgE – Model C | |||||

| Asthma | 72.6% | 75.5% | 85.7% | 57.7% | 0.74 (0.69–0.79) |

| No Asthma | 67.1% | 95.1% | 83.9% | 88.3% | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) |

| All | 71.2% | 88.5% | 85.3% | 76.6% | 0.80 (0.76–0.83) |

| Rhinitis Symptoms and (Dust Mite-IgE and/or Cockroach IgE) – Model D | |||||

| Asthma | 75.8% | 73.4% | 85.2% | 60.0% | 0.75 (0.69–0.80) |

| No Asthma | 68.6% | 94.5% | 82.8% | 88.7% | 0.82 (0.76–0.87) |

| All | 73.9% | 87.4% | 84.6% | 78.1% | 0.81 (0.77–0.84) |

| Rhinitis Symptoms and (Dust Mite-IgE and/or House Dust Trigger) – Model E | |||||

| Asthma | 96.8% | 53.2% | 80.7% | 89.3% | 0.75 (0.70–0.80) |

| No Asthma | 88.6% | 89.1% | 75.6% | 95.3% | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) |

| All | 94.6% | 76.9% | 79.4% | 93.8% | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) |

| Rhinitis and Total IgE ≥ 100 kU/L – Model F | |||||

| Asthma | 83.3% | 70.8% | 85.1% | 68.0% | 0.77 (0.72–0.82) |

| No Asthma | 76.7% | 91.4% | 77.8% | 90.9% | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) |

| All | 81.5% | 84.4% | 83.1% | 82.9% | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) |

| Rhinitis and (Total IgE ≥ 100 kU/L and/or House Dust Trigger) – Model G | |||||

| Asthma | 97.9% | 55.2% | 81.4% | 93.0% | 0.77 (0.71–0.82) |

| No Asthma | 91.8% | 87.6% | 74.4% | 96.5% | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) |

| All | 96.2% | 76.6% | 79.4% | 95.6% | 0.86 (0.84–0.89) |

| Rhinitis and House Dust Trigger – Model H | |||||

| Asthma | 90.1% | 57.3% | 80.8% | 74.3% | 0.74 (0.68–0.79) |

| No Asthma | 82.2% | 90.3% | 76.9% | 92.8% | 0.86 (0.81–0.91) |

| All | 87.9% | 79.1% | 79.8% | 87.5% | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) |

Gold standard = STR-positive AR.

AUC unable to be calculated.

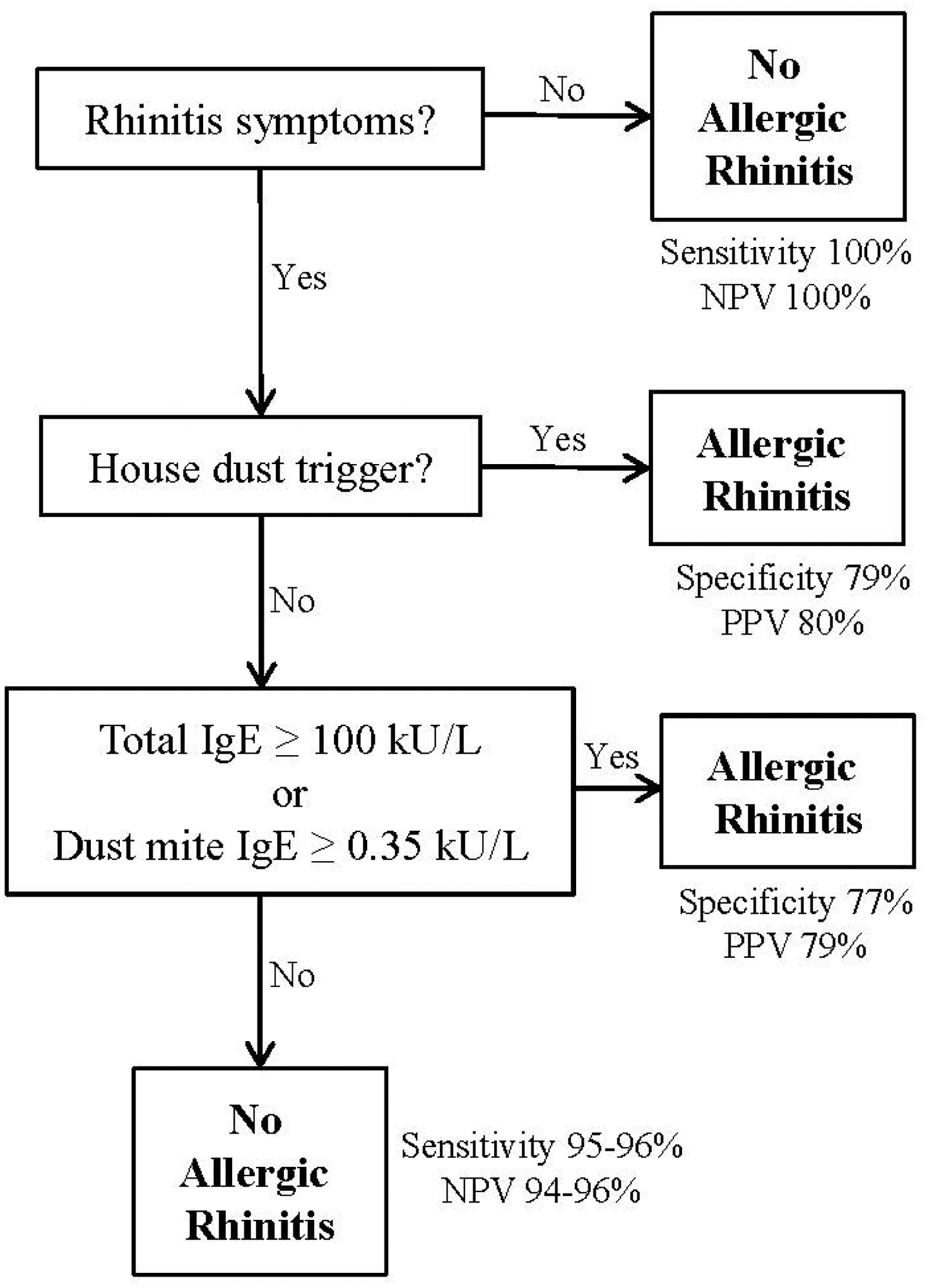

Diagnosing AR requires a careful history and physical exam, as well as targeted testing for allergic sensitization. Because skin testing or a large panel of specific IgE are usually not easily accessible to primary care physicians, we formulated an efficient algorithm to accurately diagnose AR, presented in Figure 1. We recommend that physicians inquire about: 1) recent naso-ocular symptoms apart from colds, and (if yes), 2) whether house dust triggers such symptoms. If both answers are affirmative, AR can be diagnosed. If the answer is no to house dust triggers, then physicians should measure IgE to dust mite or total IgE. AR can be diagnosed if dust mite-IgE >0.35 kU/L or total IgE ≥100 kU/L. This approach was highly sensitive, and maintained a high PPV. Because of potential detrimental effects from undertreating AR on asthma control, and relatively low risks of over-treatment (due to the safety of most AR medications), this would be particularly attractive in asthmatic children.

FIGURE 1. Schema for the Diagnosis of Allergic Rhinitis.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) presented are for both children with and without asthma.

This is the first study of the prevalence and risk factors for AR using objective markers of allergic sensitization (instead of relying on self-report) in Puerto Ricans. Limitations to our findings include the cross-sectional design, which preclude assessment of temporal relationships. We focused on PR children due to their disproportionate disease burden in asthma and atopy4, but these findings should be generalizable to other minorities. Litonjua et al. showed that total IgE is often elevated in ethnic minority women in Boston, most of whom were not diagnosed with allergic diseases7. We also previously showed that allergic sensitization is often underdiagnosed in Puerto Rican and Black children with asthma living in Hartford, CT8. Furthermore, we found that AR is underdiagnosed in children with asthma in Costa Rica, a Central American country with universal healthcare9. Therefore, our proposed diagnostic strategies for AR would likely benefit other underserved populations.

In summary, AR is markedly underdiagnosed in PR children. Physicians missed >75% and >85% of AR in children with and without asthma, respectively. Physicians could accurately diagnose AR by inquiring about the presence of rhinitis symptoms, triggers and measuring dust mite- or total IgE.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of Funding and Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by grants HL079966 and HL117191 from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by an endowment from the Heinz Foundation. Dr. Celedón served as a single-time consultant for Genentech in 2011 on a topic unrelated to this manuscript. Dr. Brehm’s contribution was supported by grant HD052892 from the NIH. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the participating children and their families for their valuable contribution to this study.

Abbreviations

- AR

Allergic rhinitis

- PD-AR

Physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis

- PR

Puerto Rican

- STR

Skin test reactivity

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Kony S, et al. Association between asthma and rhinitis according to atopic sensitization in a population-based study. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2004;113:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magnan A, Meunier JP, Saugnac C, Gasteau J, Neukirch F. Frequency and impact of allergic rhinitis in asthma patients in everyday general medical practice: a French observational cross-sectional study. Allergy 2008;63:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small M, Piercy J, Demoly P, Marsden H. Burden of illness and quality of life in patients being treated for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a cohort survey. Clinical and translational allergy 2013;3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forno E, Celedon JC. Asthma and ethnic minorities: socioeconomic status and beyond. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 2009;9:154–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazario S, Acantilado C, Alvarez M, et al. Allergist role in asthma care in Puerto Rico. Boletin de la Asociacion Medica de Puerto Rico 2011;103:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawankar R, Bunnag C, Khaltaev N, Bousquet J. Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma in Asia Pacific and the ARIA Update 2008. The World Allergy Organization journal 2012;5:S212–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litonjua AA, Celedon JC, Hausmann J, et al. Variation in total and specific IgE: effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic status. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2005;115:751–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celedon JC, Sredl D, Weiss ST, Pisarski M, Wakefield D, Cloutier M. Ethnicity and skin test reactivity to aeroallergens among asthmatic children in Connecticut. Chest 2004;125:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunyavanich S, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Laskey D, Senter JM, Celedon JC. Risk factors for allergic rhinitis in Costa Rican children with asthma. Allergy 2010;65:256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.