Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, critical care, end-of-life care, palliative care, regression discontinuity

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine if a restrictive visitor policy inadvertently lengthened the decision-making process for dying inpatients without coronavirus disease 2019.

DESIGN:

Regression discontinuity and time-to-event analysis.

SETTING:

Two large academic hospitals in a unified health system.

PATIENTS OR SUBJECTS:

Adult decedents who received greater than or equal to 1 day of ICU care during their terminal admission over a 12-month period.

INTERVENTIONS:

Implementation of a visit restriction policy.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

We identified 940 adult decedents without coronavirus disease 2019 during the study period. For these patients, ICU length of stay was 0.8 days longer following policy implementation, although this effect was not statistically significant (95% CI, –2.3 to 3.8; p = 0.63). After excluding patients admitted before the policy but who died after implementation, we observed that ICU length of stay was 2.9 days longer post-policy (95% CI, 0.27–5.6; p = 0.03). A time-to-event analysis revealed that admission after policy implementation was associated with a significantly longer time to first do not resuscitate/do not intubate/comfort care order (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6–3.1; p < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Policies restricting family presence may lead to longer ICU stays and delay decisions to limit treatment prior to death. Further policy evaluation and programs enabling access to family-centered care and palliative care during the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic are imperative.

Policies limiting family presence in hospitals are ubiquitous during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (1). We hypothesized a restrictive visitor policy implemented at our institutions on March 21, 2020, inadvertently lengthened the decision-making process for dying inpatients without COVID-19.

METHODS

To test this hypothesis, we queried the electronic health record at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Bayview Medical Center and identified adult decedents who received greater than or equal to 1 day of ICU care during their terminal admission over a 12-month period (September 1, 2019, to August 31, 2020). Patients with COVID-19 (n = 106) were excluded from analysis.

We used a regression discontinuity (RD) design (2) and specified linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, and self-reported race to estimate the effects of the policy. The primary outcome was ICU length of stay (LOS). Secondary outcomes were hospital LOS and time to first do not resuscitate (DNR), do not intubate (DNI), or comfort care order. Each RD model included hospital admission date as an independent variable, a pre-/postvariable indicating hospital admission date relative to policy implementation, and an interaction term between admission date and the pre-/postvariable. We refer to the 33 patients who were admitted before and died after policy implementation as “crossover” patients. We hypothesized that crossover patients likely had goals of care conversations occurring closer to time of death (i.e., post-policy). Therefore, we conducted sensitivity analyses, varying the date of the policy cutoff, and excluding crossover patients. Additional methods and sensitivity analyses are described in Supplementary Methods (http://links.lww.com/CCM/G323). The data used in this study were obtained through an institutional review board exemption approved by Office of Human Subjects Research at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

RESULTS

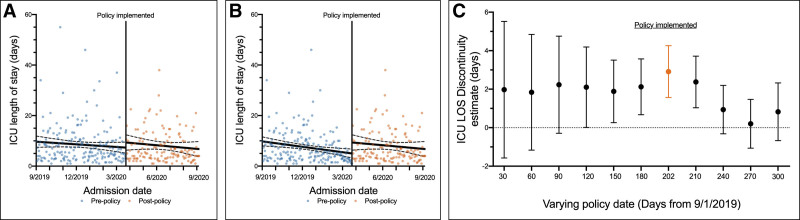

There were 940 adult decedents without COVID-19 during the study period. Among these decedents, ICU LOS was 0.8 days longer following policy implementation, although this effect was not statistically significant (95% CI, –2.3 to 3.8; p = 0.63; Fig. 1A). After excluding the 33 crossover patients, we observed that ICU LOS was 2.9 days longer post-policy (95% CI, 0.27–5.6; p = 0.03; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Impact of visitor policy on critically ill patients. A, Regression discontinuity (RD) plot of daily averages for ICU length of stay (LOS) over a 12-mo period. B, RD plot of ICU LOS with crossover patients (n = 33) excluded. Solid lines are linear regression lines, and dashed lines represent 95% CIs. C, Plot depicting the RD estimates for ICU LOS, with crossover patients (n = 33) excluded while varying the cutoff in 30-d intervals. The true policy date, March 21, 2020, corresponds to a value of 202. Cutoffs that reached statistical significance (p < 0.05) are highlighted in orange.

We performed a sensitivity analysis of the RD models with crossover patients excluded by systematically varying the date of policy implementation in 30-day intervals over the course of the study. We observed the true policy implementation date had the largest effect size and was the only date for which the cutoff was statistically significant in covariate RD models (Fig. 1C).

We found a similar result when considering total hospital LOS, including (0.5 d; 95% CI, –4.6 to 5.5; p = 0.86; Supplemental Fig. 1A, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G324; legend, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G325) and excluding crossover patients (4.8 d; 95% CI, 0.85–8.79; p = 0.02; Supplemental Fig. 1B, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G324; legend, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G325).

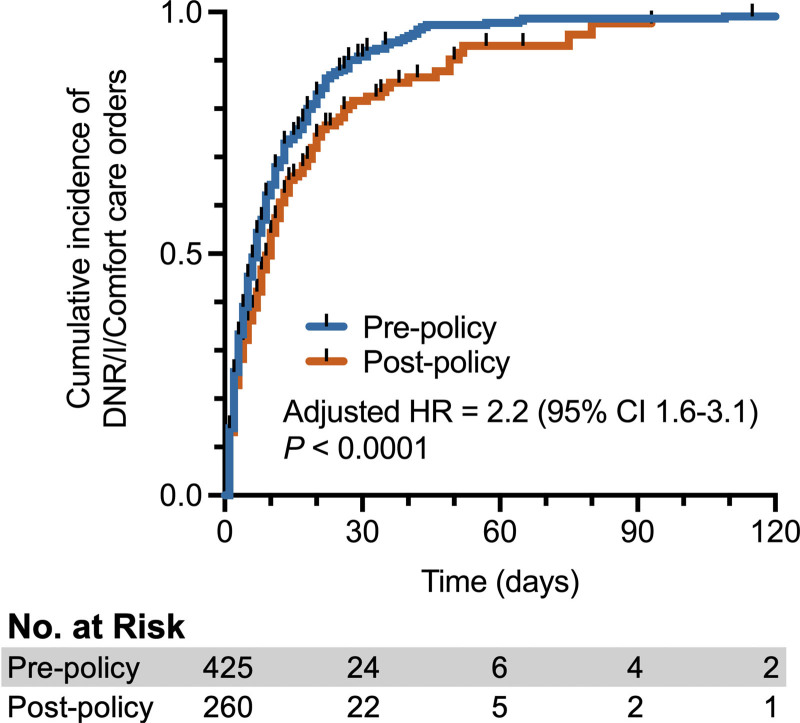

Among the 685 patients in the time-to-event analysis (including crossover patients), admission after policy implementation was associated with a significantly longer time to first DNR/DNI/comfort care order (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.6–3.1; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of do not resuscitate (DNR), do not intubate (DNI), or comfort care code status orders (n = 685). Hazard ratio (HR) obtained from multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model adjusted for age, sex, and self-reported race.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that a policy restricting family presence may have led to longer ICU stays and delayed decisions to limit treatment prior to death. This unintended consequence is particularly concerning when ICU beds become a scarce medical resource (3). The phenomenon appeared to decrease as locoregional COVID-19 positivity rates dropped and exceptions to the policy were granted with greater regularity. Further policy evaluation, as well as creative programs (4) enabling access to family-centered (1) and palliative care (5) during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, are imperative.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Dr. Turnbull’s institution received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; she received support for article research from the NIH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, et al. : Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020; 60:e93–e97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moscoe E, Bor J, Bärnighausen T: Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: A review of current and best practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015; 68:122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. : Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:2049–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor SP, Short RT, Asher AM, et al. : Family engagement navigators: A novel program to facilitate family-centered care in the intensive care unit during Covid-19. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020 Sep 15. [online ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott J, Johnson D, Wynia M: Ensuring adequate palliative and hospice care during COVID-19 surges. JAMA. 2020; 324:1393–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.