Abstract

Navigating care for patients with cancer can be overwhelming considering the multiple specialists they encounter and the numerous decisions they must make. For patients with glioblastoma (GBM), management is further complicated by a poor prognosis, feelings of isolation, urgency to treat, and cognitive decline associated with this rare and progressive disease. For these reasons, it is imperative that shared decision-making (SDM) be integrated into standard practice to ensure that the risks and benefits of all treatments are discussed and weighed with the patient’s expectations and goals in mind. In this manuscript, the importance of SDM in GBM and the potential benefits to the practice and patient are discussed from the unique perspective of advocacy leaders. Their insights from interactions with patients and caregivers provide a template for empowering patients, improving patient-physician communication and understanding, and reducing patient and caregiver anxieties. Ultimately, increased SDM may lead to a better quality of life and improved treatment outcomes.

Keywords: patient advocacy, advocacy organizations, patient-centered care, brain tumor, oncology

Introduction

For patients with glioblastoma (GBM), the practice of shared decision-making (SDM) can lead to improved patient quality of life (QoL) and better patient outcomes.1,2 The importance of evaluating the patient perspective on symptoms and care is widely recognized in oncology, and efforts in neuro-oncology are increasingly focused on implementation of appropriate patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessments in clinical trials and clinical practice,3,4 and development of a patient-centric care framework involving PROs and patient advocacy groups.5 Advocacy groups have a unique window into the patient experience through their interactions with patients who have brain tumors and can provide insights into key elements that help to define an effective SDM process. These elements include the importance of incorporating the “patient voice,” asking the patient what is important to them and what their QoL looks like, presenting all treatment plans to the patient to help them determine their best individual treatment plan, and asking the patient how they feel about their treatment plan.

Because of the importance of SDM in treating GBM, brain-tumor patient advocates met in the spring of 2019 to discuss how to effectively implement SDM into practice. This article summarizes brain-tumor patient advocates’ perspectives on SDM and should help to inform health care providers (HCPs) who treat patients with GBM. Brain-tumor patient advocates feel SDM is key to driving patient-centered care, and this article identifies how HCPs can and should incorporate SDM into every level of treatment for all patients with GBM.

Background

Healthcare decision-making processes fall along a spectrum from paternalism, a more traditional model that relies on physician technical competence, moral sensitivity, and control to make treatment decisions on behalf of patients,6,7 to informed choice, in which the patient makes his/her own decision.7 SDM represents the “middle ground” between these extremes.7 SDM is also distinct from Advanced Care Planning (ACP), which aims to involve patients and caregivers in planning for eventual palliative and end-of-life care,8 and from palliative care, which aims to relieve patient symptoms and patient and caregiver distress and improve quality of life throughout the course of illness.9,10 Both ACP and palliative care are contexts in which SDM should be applied.

Shared decision-making, a term first promulgated in the US by a Presidential Commission in 1982, is well described in the medical literature and often used in the healthcare setting.6,7 In general, SDM refers to a collaborative process in which patients, caregivers, and HCPs make care decisions together after considering the risks, benefits, and alternatives to all available treatments while taking into account the patient’s values, preferences, life situation, and desires.7 SDM has been identified as a key element of patient-centered care and patient-reported QoL.1,2

In oncology, SDM is particularly important considering the complexity of the many medical decisions in cancer care as well as the risks and benefits of treatment choices that may be weighed differently by individual patients.11 However, studies have shown that SDM implementation is poor in the neurosurgical setting and in the care of cancers without curative potential, including GBM.12,13 For patients with GBM, the process of SDM can be further complicated by the cognitive decline associated with the progressive disease.14 To better understand SDM in GBM and the perspective of the patient, a roundtable discussion was held on May 23, 2019, in New York, NY, with a panel of interested patient advocacy leaders from organizations focused on brain tumors. Representatives from advocacy organizations that have provided support to patients with brain cancer and their families for many years, including some who had family members with brain cancer and direct caregiving experience, were invited to participate. These organizations were the Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research & Information, the National Brain Tumor Society, the American Brain Tumor Association, CancerCare, Head for the Cure Foundation, and the EndBrainCancer Initiative. Their unique insights, along with additional contributions from the authors, serve as the basis for this publication. Dellann Elliott Mydland from the EndBrainCancer Initiative was unable to attend the roundtable discussion but agreed to provide her expertise as an author of the manuscript. The authors of this manuscript include all except two of the roundtable participants who declined because they were unable to commit to fulfilling the requirements for authorship.

Discussion

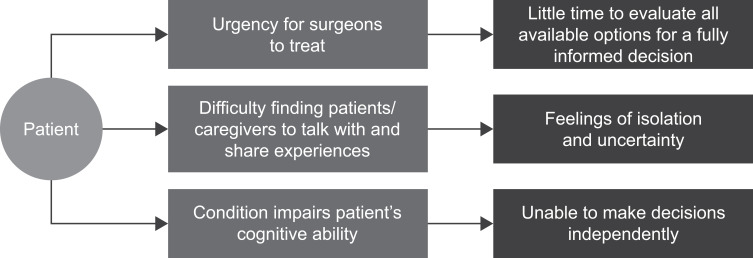

The advocacy leaders agreed that the term shared decision-making is not commonly used among patients and caregivers because it is considered an implicit part of their healthcare and not a separate process. However, SDM remains to be fully integrated into standard practice; therefore, patient experiences may vary from provider to provider, and center to center, due to inherent differences among individuals and practice settings. Advocacy leaders also agreed that the core tenets of SDM translate when treating patients with GBM and that the challenges of SDM in oncology are exacerbated by the difficult nature of GBM (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Challenges to shared decision-making for patients with glioblastoma.

In particular, advocacy leaders discussed how the poor prognosis and rarity of GBM can make it difficult for patients to find other GBM patients and caregivers with whom to talk and share experiences. This often leaves them feeling isolated and unsure of what the diagnosis means for them personally. They also noted that the intense sense of urgency to typically perform surgery within 72 hours of an initial diagnosis of a brain mass can leave little time for patients to evaluate available treatments and make a fully informed decision. Further, GBM may leave patients cognitively impaired and unable to make decisions for themselves.

Via the roundtable discussion, advocacy leaders elaborated on the process of SDM from their unique perspective to help better meet the needs of HCPs, as well as the patients and their caregivers who face this deadly disease. Advocacy experts stressed that SDM in oncology, particularly for patients with GBM, should not be a singular, isolated event. The concept of SDM extends beyond the initial encounter between a patient and an individual HCP. It is an ongoing process that occurs at various stages throughout the patient care journey and typically involves the extended treatment team as well as family members. The advocacy leaders stressed that communication should occur early, be open, and be repeated throughout a series of conversations. This may be difficult to implement in a care setting for a variety of reasons, including transitions of care between specialists, time constraints for the treatment team, cognitive challenges related to GBM, and patients feeling unable to participate because they do not understand the disease and treatment options. Advocacy organizations can help facilitate SDM by providing the patient and family with educational materials, answers to common questions, and continuity of support throughout the journey.

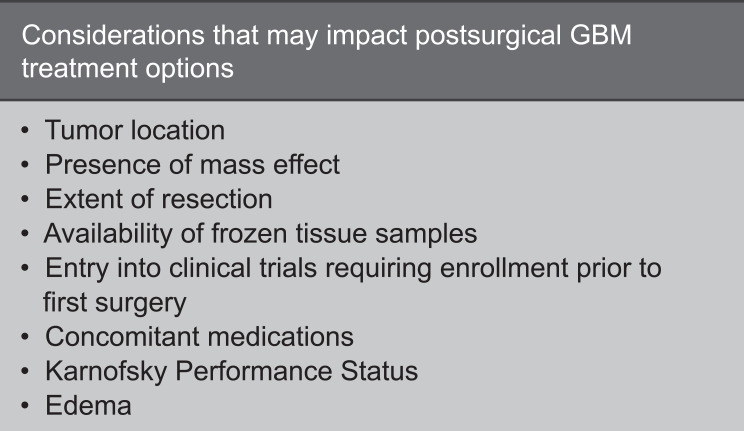

Neurosurgeons are generally the first providers to engage in discussions with patients about their GBM diagnosis. They are considered the first point of connection in the process of SDM between the patient and the multidisciplinary care team, which also includes, but is not limited to, a radiation oncologist, neuro-oncologist, medical oncologist, neuropsychologist, and nursing staff. Because brain surgery is often the first step in the treatment journey, advocacy leaders note that SDM for these patients usually happens after treatment has already begun, as does their outreach to patient advocacy groups. In fact, the majority of advocacy leaders estimated that as little as 10% of patients who contact their advocacy groups have not yet undergone surgery, and many are already in the recurrent stages of their disease. When faced with the possible diagnosis of GBM, patients and families often report feeling overwhelmed and a need to make decisions quickly due to the poor prognosis and limited treatment options. However, surgery itself is predictive of outcomes in GBM, and various details of surgical treatment may further impact the availability of postsurgical treatment options.15,16 This highlights a need for SDM prior to surgery, when a brain tumor is initially confirmed, and before the pathology results are shared with the patient, caregiver, and/or family (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Presurgical talking points to consider for patients with glioblastoma (GBM).

For this reason, advocacy leaders strongly encourage neurosurgeons and the neurosurgical team to expand their conversations with patients beyond the details of surgery alone to include information on next steps and all available treatment options, including Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatment options and clinical trials the patient is eligible for at all treatment sites, not just the site where the patient is being treated. As staying informed of medical and radiologic treatment options and clinical trials may be challenging for neurosurgeons, a high-level discussion with patients accompanied by referral to an advocacy organization for additional information can open the dialogue and help to meet the needs of patients and families who are interested in more details on specific options at this stage. Because surgery is typically the first treatment intervention, patients often look to the neurosurgeon for advice and place a high level of trust in their recommendations. Thus, the neurosurgeon plays an important role in establishing rapport and building patient confidence and peace-of-mind that they will receive the best possible care through a multidisciplinary approach of specialists and treatment interventions. This message should then be extended across the team and continually reinforced during all HCP touchpoints throughout the patient’s journey. This strategy is particularly important because the neurosurgeon’s patient contact may be minimal following postop recovery and throughout the treatment journey.

The neuro-oncologist, medical oncologist, and/or radiation oncologist provide continuous care throughout the course of the disease and therefore have a relationship with the patient and caregivers at every postsurgical stage of treatment. As the patient-provider relationship unfolds, inconsistencies in treatment discussions between the different care team members can occur, creating increased anxiety and confusion when the patient is faced with variable, or even contradictory, treatment decisions. To avoid this path of uncertainty, advocates encourage care teams to align and create unbiased, coherent, and uniform narratives that patients and caregivers can understand without raising concerns that their care team is misaligned.

Advocacy leaders often receive calls from both patients and caregivers seeking advice when receiving information that is inconsistent, conflicting, or does not reflect the patient’s goals. This may contribute to patient/caregiver anxiety and can result in skepticism and lack of trust. Moreover, conflicts of interest can arise among HCPs due to external factors that may influence their decisions, such as the availability of clinical trials, time needed to discuss treatments, location of care, insurance benefits, cost, and the healthcare system/institution the HCP is affiliated with. This highlights the need for consistent and unbiased delivery of information by all members of the multidisciplinary treatment team.

For the patient to fully benefit from a multidisciplinary team approach, the entire treatment team must be informed about the patient and their goals of care, be aligned on their treatment plan, and have a coordinated approach for disseminating this information in a thoughtful, consistent, and repetitive fashion. Recognizing that the primary provider may change as treatment progresses, patient advocates also encourage providers to align on and designate the role of primary provider at each step of the treatment journey and to effectively communicate this role to the care team and patient. Patients should also be advised that they should seek a second opinion if they have any concerns about their care, and when they do, communication and treatments may not be consistent between centers. Advocates further encourage providers to improve communication across cancer centers to better understand the various approaches and treatment options being used and discussed with patients outside their practice.

A cornerstone of successful SDM is effective communication between all members of the treatment team, including the patient, their immediate caregiver, and family. Patients may lose confidence in their provider when information is presented poorly or communication does not encourage a two-way dialogue. Of course, advocacy leaders agree that effective communication cannot take place without first understanding the patient and their individual needs. Before discussing treatment options, HCPs should know how aggressive their patient would like their treatment to be and any personal goals or milestones they would like to reach. Knowing this information enables HCPs to communicate with patients clearly, definitively, and with understanding and empathy to their individual needs and situation. Not understanding or discussing the patient’s goals at the onset of treatment discussions may lead to delays in decision-making or treatment access, which can have a negative impact on patient and caregiver QoL (Figure 3). Scheduling a telehealth visit for the day after the initial visit may help minimize these delays, as patients will have had some time to process their situation and think of questions for the neurosurgical team. Having the conversation in the comfortable surroundings of home may reduce distractions and patient stress. This visit could be conducted by the nurse practitioner or resident on the team to reduce the neurosurgeon’s time commitment and, as an incentive, in the current healthcare delivery climate, the practice should be reimbursed for these visits.17 These discussions should be revisited throughout the course of treatment as patient goals may change over time. If the neurosurgeon refers patients and families to an advocacy organization at the initial visit, advocates can provide education and resources to facilitate SDM for patients who want to participate.

Figure 3.

Outlining effective communication for successful shared decision-making (SDM) in glioblastoma.

When engaging patients and caregivers, HCPs may encounter those with poor health literacy and/or diminished cognitive abilities. Patients with brain tumors often face cognitive symptoms that can prevent them from fully understanding or remembering the information provided. This is exacerbated by a diagnosis of GBM, which can also leave patients feeling overwhelmed and emotionally unprepared to provide input on their course of care. These communication challenges reinforce the need for SDM to be a consistent and ongoing process, both in person during office visits and via telehealth web conference, phone, text, or email when the patients may have questions between their scheduled appointments. The logistical considerations involved in implementing this process will depend upon the technologies available to the care team and the patients and family members. Options could include reminders in the electronic medical records software to prompt a follow-up, use of a care coordinator to assess the need for a follow-up, and providing patients and families with access to a patient portal with messaging capabilities. Advocates may also assist by providing resources and information appropriate to each stage of the journey. Advocates note that keeping conversations brief and reinforcing key information throughout the patient journey can help improve understanding and retention of information among these patients. It is also recommended to both ask and answer questions with the understanding that patients may not readily know what questions to ask. Caregivers also play a critical role in capturing information and often communicate the patient’s intent if they are unable to participate fully in the SDM process or lack the confidence to make decisions on their own.

While family and/or caregivers are generally highly involved in the SDM process, sometimes disagreements and even conflicts of interest may occur. Family members may have differing opinions about the best course of treatment for the patient or may not be ready to accept their loved one’s prognosis. For this reason, one family member/caregiver may want to take a more aggressive approach to treatment than what another family member/caregiver, or ultimately the patient, desires. To manage these potential conflicts, advocacy leaders recommend that HCPs consult the patient directly to determine their desired level of family/caregiver involvement in making decisions about their care. Importantly, patients should be encouraged to designate one individual to represent their interests and guide decisions early in the disease process. This is particularly important for patients facing cognitive decline from GBM, as concordance between patients and their representatives regarding the patient’s condition and quality of life can be good initially but may diminish as cognitive impairment progresses.18 Therefore, conversations and alignment between patients and their representative should be undertaken as early in the disease journey as possible to help ensure that patient wishes are followed throughout the course of care. Advocates note that the patient’s point of view should never be dismissed and that including family members in SDM should always be enacted at the patient’s discretion.

Ultimately, it is the patient who decides how they want to treat their disease. For them to make the most informed decision possible, the risks and benefits of all treatment options should be reviewed in an unbiased fashion, along with information about how each treatment may align with their individual goals. Although advocacy groups are not traditionally considered a part of the treatment care team for patients in oncology, or more specifically for patients with GBM, they often serve as a bridge between HCPs, patients, and caregivers in the delivery of unbiased and complete information (Figure 4). Advocacy groups play an important role in fostering patient awareness and participation in SDM by educating patients about resources available to them throughout the course of their disease. Advocacy groups also aim to provide a neutral voice, especially when those involved are not aligned.

Figure 4.

Inclusion of advocacy groups in the process of shared decision-making for patients with glioblastoma.

When a treatment is selected, it is imperative that providers support patients in achieving maximum treatment compliance through prevention and management of side effects to ensure the patient has the best chance of benefiting from their treatment. Advocates note that once a treatment is selected, the process of SDM does not stop. In fact, it should deepen. All treatment decisions should continue to align with the goals of the patient and be readjusted if and when patient goals change. Open, ongoing communication via consistent patient follow-up can help identify and address symptoms and challenges that may be affecting treatment goals, leading to improved survival and QoL.1,2

When asked to identify how SDM can positively impact patients with GBM, advocates identified ways to achieve six key outcomes:

Refer to a favorite advocacy organization and websites for patient education materials to enhance dissemination of information

Describe all potential treatment choices and explain the significance of each to help patients choose the course of care that is right for them, increasing patient empowerment

Use a care coordinator to ensure that patients see the right specialists at the right time and have access to treatment, improving patient-centric care

Encourage patients to seek 2nd opinions to enrich trust and shared responsibility

Follow up with patients at home after they have a chance to digest the information provided at a visit, and refer to online or in-person patient support groups to reduce patient and caregiver anxieties

Take patient QoL preferences into account when discussing how aggressive a treatment plan to implement for potential improvement in patient-reported QoL and treatment outcomes

Together, all of these strategies foster trust and shared responsibility between the patient, caregiver, and treatment team, allowing for greater accountability among all involved and improved treatment adherence on the part of the patient.19 Ultimately, incorporating SDM throughout a patient’s journey with GBM may improve their QoL and treatment outcomes.1,2

Conclusions

The benefits of SDM are well documented.1,2 For HCPs, they include improved quality of care and increased patient satisfaction. For patients, SDM has been shown to improve their healthcare experience and adherence to treatment recommendations and may potentially improve patient outcomes.20 Based on their real-world experience interacting with patients, advocacy leaders believe there is an opportunity to improve SDM, as well as the role advocacy groups play in the process. Multidisciplinary alignment ensures a consistent approach to communication. Multiple conversations across HCPs that address all treatment options allow for a more comprehensive overview and enhance the dissemination of information. Open communication empowers patients and caregivers to vocalize goals, expectations, and values with HCPs, resulting in increased goal alignment and treatment planning that is more patient centric. Engaging patients and caregivers in a two-way dialogue enables them to feel more comfortable and confident in sharing their viewpoints and wishes, such as treatments the HCP may not have discussed, ultimately allowing for more patient-driven care. For patients with GBM, advocates agree that this style of communication may also help reduce patient/caregiver anxieties through emotional burden sharing.

The voice of the patient should be heard and incorporated into all aspects of the GBM treatment journey. For this to happen, all members of the GBM treatment team, including neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists, neuropsychologists, nursing staff, and advocacy groups, should engage in the process of SDM throughout the course of care and, in doing so, help to fully integrate SDM into standard practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Brain Tumor Society and Amanda Bates for contributions to this manuscript as advisors. We would also like to thank Brian Tomlinson for his participation in the roundtable discussion on May 23, 2019, in New York, NY, as a representative of CancerCare. Assistance with manuscript preparation, development of tables and figures, and process support was provided by Amanda Mower, PhD, and Marsha Scott, PhD, at Impact Communication Partners and funded by Novocure.

Funding Statement

The roundtable discussion and manuscript development were funded by Novocure.

Disclosure

All authors have served on an advisory board for Novocure and received non-financial support. Novocure employees were involved in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript but did not influence insights from the authors that served as the basis for this publication. Novocure employees participated in discussions about submission of the manuscript for publication but did not influence the authors’ decision regarding the journal to which the manuscript would be submitted.

The Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research & Information, Inc; American Brain Tumor Association; Head for the Cure; National Brain Tumor Society; CancerCare; and EndBrainCancer Initiative have received sponsorship from Novocure. AM is a consultant for xCures and has received grants from Novocure outside of this submitted work. DEM reports grants from AbbVie, Agios/AGIOS, GT Medical, and Genentech; grants and personal fees from Novocure; sponsorship from Karyopharm; and grants and sponsorship from Foundation Medicine, outside of this submitted work. MA reports grants and honoraria from Novocure outside of this submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dirven L, Armstrong TS, Blakeley JO, et al. Working plan for the use of patient-reported outcome measures in adults with brain tumours: a response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):e173–e180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30004-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenlund L, Degsell E, Jakola AS. Moving from clinician-defined to patient-reported outcome measures for survivors of high-grade glioma. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:267–276. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S179313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leeper H, Milbury K. Survivorship care planning and implementation in neuro-oncology. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(Suppl7):vii40–vii46. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.President’s commission for the study of ethical problems in medicine and biomedical and behavioral research; 1982. Making Health Care Decisions: The Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship. Available from:https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/559354. Accessed January17, 2020.

- 7.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritz L, Dirven L, Reijneveld JC, et al. Advance care planning in glioblastoma patients. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(11):102. doi: 10.3390/cancers8110102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip J, Collins A, Brand C, et al. A proposed framework of supportive and palliative care for people with high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(3):391–399. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vierhout M, Daniels M, Mazzotta P, et al. The views of patients with brain cancer about palliative care: a qualitative study. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(6):374–382. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population. Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. The National Academies Press; 2013. Available from:http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=18359. Accessed January17, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brom L, De Snoo-trimp JC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: a qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):69–84. doi: 10.1111/hex.12434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corell A, Guo A, Vecchio TG, et al. Shared decision-making in neurosurgery: a scoping review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2021;163:2371–2382. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04867-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triebel KL, Martin RC, Nabors LB, Marson DC. Medical decision-making capacity in patients with malignant glioma. Neurol. 2009;73(24):2086–2092. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67bce [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li XZ, Li YB, Cao Y, et al. Prognostic implications of resection extent for patients with glioblastoma multiforme: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Sci. 2017;61(6):631–639. doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.16.03619-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds; for the Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorodeski EZ, Goyal P, Cox ZL, et al. Virtual visits for care of patients with heart failure in the era of COVID-19: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail. 2020;26(6):448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ediebah DE, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Impact of neurocognitive deficits on patient–proxy agreement regarding health-related quality of life in low-grade glioma patients. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(4):869–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1426-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2014;35(1):114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The CAHPS ambulatory care improvement guide: practical strategies for improving patient experience; 2013. Available from:https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/quality-improvement/improvement-guide/improvement-guide.html. Accessed January28, 2020.