Abstract

Fleshy fruits can be divided between climacteric (CL, showing a typical rise in respiration and ethylene production with ripening after harvest) and non-climacteric (NC, showing no rise). However, despite the importance of the CL/NC traits in horticulture and the fruit industry, the evolutionary significance of the distinction remains untested. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that NC fruits, which ripen only on the plant, are adapted to tree dispersers (feeding in the tree), and CL fruits, which ripen after falling from the plant, are adapted to ground dispersers. A literature review of 276 reports of 80 edible fruits found a strong correlation between CL/NC traits and the type of seed disperser: fruits dispersed by tree dispersers are more likely to be NC, and those dispersed by ground dispersers are more likely to be CL. NC fruits are more likely to have red–black skin and smaller seeds (preferred by birds), and CL fruits to have green–brownish skin and larger seeds (preferred by large mammals). These results suggest that the CL/NC traits have an important but overlooked seed dispersal function, and CL fruits may have an adaptive advantage in reducing ineffective frugivory by tree dispersers by falling before ripening.

Keywords: seed dispersal, bird, bat, mammal, dispersal syndrome, frugivore

1. Introduction

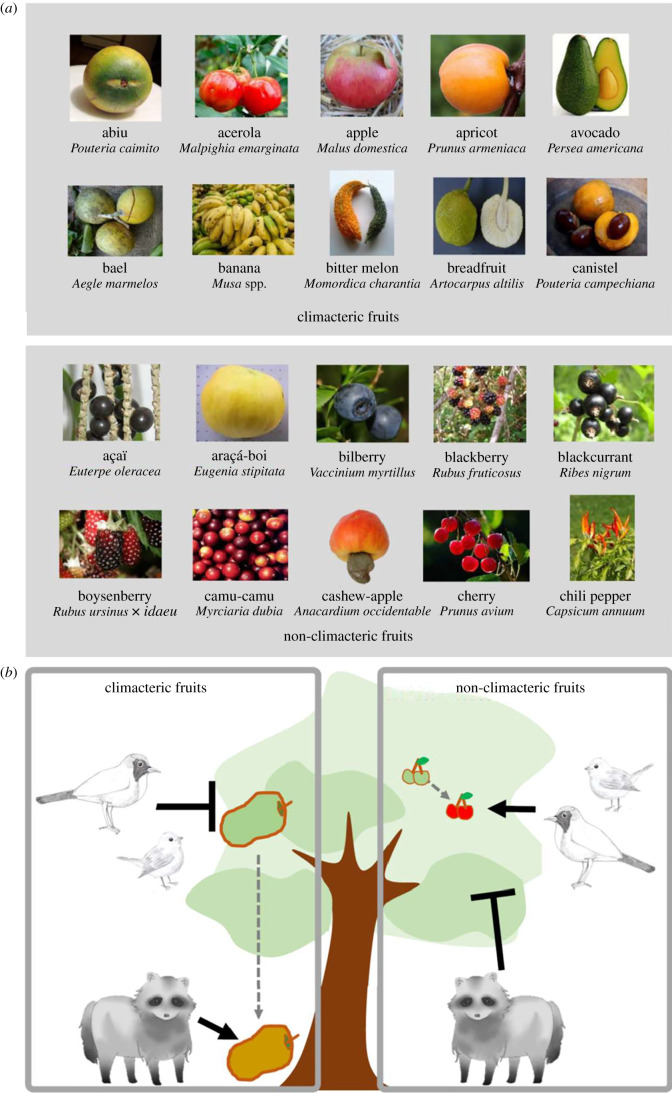

Fruit ripening and frugivorous animals play important roles in seed dispersal [1–4]. Many studies have revealed fruit traits shaped by seed dispersers, such as colour, size, odour, nutrients and defence chemicals [1,5], as explained by the dispersal syndrome hypothesis [6]. However, climacteric (CL) and non-climacteric (NC) traits of edible fruits have been largely overlooked by ecologists. CL fruits (such as apple, banana, mango and avocado) usually show a rise in respiration and ethylene production with ripening after harvest. NC fruits (such as grape, strawberry, cherry and citrus) show neither [7–9] (figure 1a). Although many studies of the physiological and molecular mechanisms and breeding or genetic modification of CL/NC traits of fruit crops have been carried out [10,11], there are no reported studies of the CL/NC traits of uncultivated, wild species, and the evolutionary significance of CL/NC types has not been tested.

Figure 1.

(a) The first 10 climacteric and non-climacteric fruits in alphabetical order (detailed list in electronic supplementary material, table S1). All fruit pictures are reproduced from Wikimedia Commons (see electronic supplementary material, S1). (b) Schematic of the concept of ecological function for climacteric and non-climacteric fruits.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that the characteristics of CL fruits, which ripen after release from the parent plant, are an adaptation to ground dispersers [12], such as large herbivorous and omnivorous mammals, which feed on fruits on the ground; and that those of NC fruits, which ripen only on the plant, are an adaptation to tree dispersers, such as birds, bats and primates, which feed on fruits in the tree (figure 1b). By falling before ripening, CL fruits may have an adaptive advantage in reducing ineffective frugivory by tree dispersers, with smaller gape and body sizes, because traits such as large seed and fruit size favour herbivorous ground mammals.

To test the hypothesis, we collected information on the CL and NC traits, seed dispersers and seed dispersal-related traits (skin colour and seed size) of 80 fruits by literature survey and statistically analysed the association between them. If this hypothesis is correct, fruits dispersed by tree frugivores are more likely to have NC traits with red or black skin colours and smaller seeds, whereas fruits dispersed by ground frugivores are more likely to have CL traits with brown or green skin colours and larger seeds [13,14]. To be eaten by ground dispersers, CL fruits must avoid being eaten by birds on the tree. Green or brown fruits are inconspicuous on the tree and may thus avoid feeding damage by birds [15].

2. Material and methods

(a) . Selection of fruit species

To determine the fruit species to be analysed, we reviewed species lists in a standard textbook [9] and websites (https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fruits, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Edible_fruits). We excluded fruits that met the following criteria: (i) fruits whose climacteric (CL) or non-climacteric (NC) features were not determined; (ii) fruits with intraspecific variation in CL/NC traits; (iii) fruits with no information on the seed dispersal agents in wild populations or wild relatives; (iv) all Citrus fruits, because the phylogenetic relationships are complicated, and the forms and habits of ancestral or wild Citrus fruits are largely unknown [16]; and (v) fruits of the subgenus Prunus, except for Prunus armeniaca, to avoid potential pseudo-replication, as this species complex includes many crops with shared ancestry [17]. We thus filtered 80 fruits for statistical analysis (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(b) . Literature survey for climacteric/non-climacteric traits

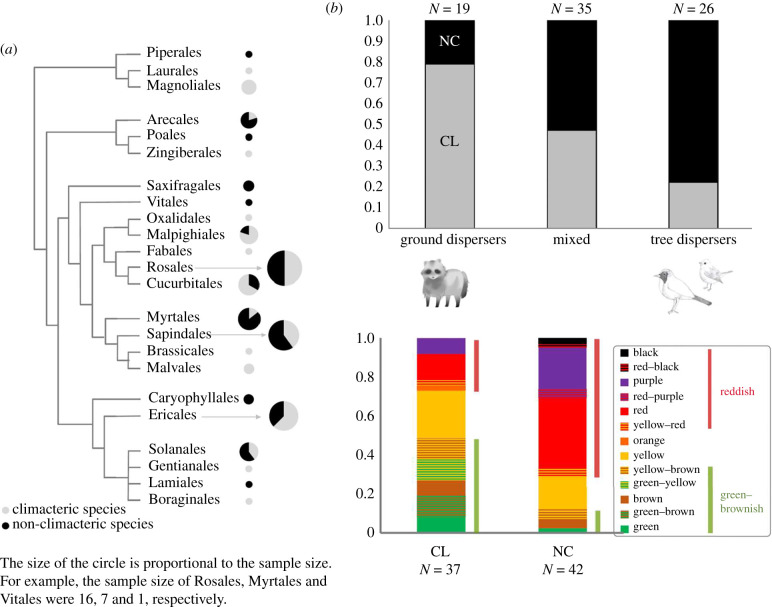

The CL/NC traits of each target species were determined from published papers (electronic supplementary material, table S1). To estimate the phylogenetic distribution of CL/NC fruits, we calculated their proportions in each order and mapped them on a postulated angiosperm phylogeny [18] (figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Phylogenetic distribution of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits. The phylogeny was modified from Cole et al. [18]. Circle size reflects the relative number of species. (b) Proportions of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits dispersed mainly by ground animals, tree animals and both. (c) Proportions of skin colour of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits.

(c) . Literature survey for seed dispersal agents

To determine the potential seed dispersal agents of the fruits, we searched studies in Google Scholar with the taxonomic name of each fruit and ‘seed dispersal’. As fruits of cultivated plants in orchards will have different frugivores from those of ancestral or wild populations, we excluded reports of the seed dispersal of cultivated plants and focused on wild populations or congeneric species. As a result, 276 reports for 80 fruits were collected (electronic supplementary material, table S2, median = 3 per species). Ideally, the types of dispersal agents should be based on the relative proportions of fruit removal by each frugivore group, corrected by their effectiveness in terms of seedling recruitment [3]. However, such information is lacking for most fruits. Thus, following previous studies [3,5], we assigned them to three broad categories: dispersed by tree animals (birds, bats and primates), dispersed by ground animals (non-flying birds, mammals and reptiles) and mixed. To test our hypothesis, we need quantitative assessments of seed dispersal or fruit consumption in wild populations of our target species. However, little literature is directly applicable to our hypothesis, so we included literature on ancestral and congeneric species. To mitigate the variations of ‘suitability’ of the literature and potential bias in the classification of dispersal agents, we created multiple datasets from the 276 reports according to the ‘suitability’ of the dispersal records and target species in the literature (electronic supplementary material, S1). Because primates can be both ground and tree dispersers, we created datasets that assumed both. Based on the above three factors ((i) variations in target species, (ii) suitability of the seed dispersal or fruit consumption records, and (iii) classification of primates), we created 18 datasets (electronic supplementary material, S1): 3 types of target species × 3 types of seed dispersal or fruit consumption records × 2 types of primates. All datasets were statistically analysed to examine the overall support for the hypothesis.

(d) . Literature survey of seed length and skin colour

For the skin colour and seed length of each fruit, we used a standard textbook [19], Google Images and literature surveys by Google Scholar (electronic supplementary material, table S3 and S1). Following previous studies such as [20], the skin colour was classified into 13 types (black, red–black, purple, red–purple, red, yellow–red, orange, yellow, yellow–brown, green–yellow, brown, green–brown and green, figure 2c). We grouped these 13 colours into three categories based on the colour preference of dispersers: reddish for birds, green–brownish for mammals and yellowish (electronic supplementary material, S1; figure 2c).

(e) . Statistical analysis

First, we determined whether the types of seed dispersers are associated with the CL or NC traits by using phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) regressions to account for the effects of phylogenetic relationships among fruit species (electronic supplementary material, S1). We considered the type of seed disperser (ground disperser, tree disperser or mixed) and the growth form (herb or tree) as explanatory variables. This analysis was performed on the 18 datasets. Second, we examined whether the CL/NC trait of each fruit is associated with skin colour or seed length by using PGLS regression. We treated the colour category as the response variable on an ordinal scale (1, reddish; 2, yellowish; 3, green–brownish). We treated the seed length of each fruit as the response variable. Likelihood ratio tests were used to calculate p-values for all models.

3. Results

The phylogenetic pattern of CL and NC fruits suggests that the traits have arisen repeatedly in the evolution of angiosperms, without phylogenetic constraint (figure 2a). In most datasets, the PGLS regressions showed that the type of seed dispersal agent was tightly associated with the CL/NC traits of the fruits (figure 2b; electronic supplementary material, S2): fruits dispersed by tree animals (such as birds and bats) are more likely to be NC, and fruits dispersed by ground animals (such as large herbivores and omnivores) are more likely to be CL. The results of the statistical analysis were generally the same, regardless of the type of dataset (15 out of 18, electronic supplementary material, S2). These results were highly consistent among datasets.

We found a significant difference in skin colour between CL and NC fruits (F = 36.218, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001): NC fruits are more reddish and CL fruits are more green–brownish (figure 2c). We found a significant difference in seed length between CL and NC fruits (F = 4.356, d.f. = 1, p = 0.041): seeds of CL fruits are longer than those of NC fruits (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

4. Discussion

These results support the hypothesis that fruit ripening processes (CL versus NC) are adapted to the seed dispersal mode. The CL/NC traits are thus important in the dispersal of fruit seeds. The CL phase of increased respiration during ripening is associated with rapid conversion of starch and other carbohydrates to sweeter and more easily digested sugars, the emission of aromatic volatile compounds and softening [12]. These CL characteristics after fruit fall improve the efficiency of seed dispersal by ground seed dispersers. Because CL fruits have larger seeds (electronic supplementary material, figure S1, such as in mango, jackfruit and avocado), ground-dwelling animals that tend to be larger on average than tree frugivores may be effective for seed dispersal. In addition, CL fruits tend to have greenish or brownish skin colour (figure 2c), which may hide CL fruits from tree dispersers when still on the tree. Therefore, by falling before ripening, CL fruits may have an adaptive advantage in reducing ineffective frugivory. This evolutionary scenario was mentioned [12] but had not been evaluated. CL/NC traits may have an important function in transferring the fruit to the appropriate location for access by effective seed dispersers. However, there is large variability in seed size and skin colour that cannot be explained by this scenario. In addition, it is possible that there is weak selective pressure on the skin colour of CL fruits due to the nocturnal and dichromatic nature of many ground-dwelling mammals. The relationship between seed disperser type, CL/NC traits and other seed dispersal traits will need to be further explored in uncultivated wild species.

Since the literature used as references varied in its suitability for hypothesis testing and the classification of primates was ambiguous, we created multiple datasets. However, literature variations in datasets had almost no effects on overall results. This result suggests that the effect of disperser type on CL/NC traits is consistent, despite our use of several types of target species and our concerns about the classification of primates.

In contrast with the extensive studies in horticulture, the CL/NC traits have been largely overlooked by ecologists. To date, no study has elucidated the CL/NC traits of uncultivated, wild species. Based on the concept presented here, we predict that all wild fruits can be divided between CL and NC types, and that the distinction is associated with the type of seed disperser. The strong association between the CL/NC traits and seed dispersers (figure 2b) suggests that CL/NC traits play a central role in the seed dispersal syndrome. Thus, comprehensive assessment of CL/NC and other associated traits is needed in wild fruits. These datasets allow us to use more sophisticated analytical approaches (e.g. phylogenetic comparative methods, [21]) to evaluate the joint evolution of fruit traits. Second, the onset of ripening in edible fruits is associated with many morphological and physiological trait variations such as colour change, altered sugar metabolism, fruit softening, changes in texture, synthesis of volatile compounds and increased susceptibility to pathogen infection [22]. Our concept could be useful for integrating these trait complexes in fruits. For example, it can be predicted that NC fruits are less sweet (have lower sucrose content) and less aromatic than CL fruits, because some frugivorous birds such as passerines cannot digest sucrose [23] and because the olfactory sense is less developed in most bird dispersers than in mammals [24].

The ripening of climacteric fruits is controlled by plant hormones such as ethylene and abscisic acid. For example, ethylene application induces the production of endogenous ethylene, which accelerates fruit ripening (positive feedback in ethylene production) [8,22]. However, the process and speed of ethylene-induced ripening vary widely between fruit species [25]. For example, some cultivars of peach (i.e. melting fresh) show rapid ethylene production and softening after harvest [26], but some cultivars ripen slowly [27]. These variations may be shaped by artificial selection during the cultivation process, but they may also be influenced by ecological factors (e.g. the expected time to be eaten by ground seed dispersers). Future research will be required not only on the differences between climacteric and non-climacteric fruits, but also on the evolutionary ecology of the variation within climacteric fruits.

As our study is the first of its kind, it has limitations associated with the approach. Firstly, we used CL/NC trait data of cultivated species owing to the lack of information on CL/NC traits in uncultivated, wild species. To understand the evolutionary and ecological importance of CL/NC traits, the characteristics of many wild fruits in their ecological context must be evaluated. Secondly, we determined broad categories of fruit skin colour from pictures and descriptions in a standard textbook [19] and from online data. This broad categorization of skin colour is a commonly used approach in seed dispersal research [28–30], but it precludes information other than visible light, saturation, brightness and spectral pattern. Collecting more detailed information on fruit skin colour may provide a more accurate assessment of the relationships among CL/NC traits, fruit colour and seed dispersers. Efforts to link horticultural science with the evolutionary ecology of seed dispersal may be fruitful in improving our understanding of proximate and ultimate causes of fruit ripening.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Honda, M. Shibata and D. Takada for helpful discussions, K. Izumi and K. Ichikawa for the initial inspiration for this study, and K. Yoshioka and H. Sakamoto for the illustration.

Data accessibility

All data were uploaded as electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S4.

Authors' contributions

Y.F. and Y.T. conceived, designed and executed the study. Y.F. wrote the first draft. Y.F. and Y.T. revised the manuscript. Both authors agree to be held accountable for the content therein and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

We have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

References

- 1.Herrera CM, Pellmyr O (eds). 2009. Plant animal interactions: an evolutionary approach. Hoboken, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunderle JM. 1997The role of animal seed dispersal in accelerating native forest regeneration on degraded tropical lands. For. Ecol. Manage. 99, 223-235. ( 10.1016/S0378-1127(97)00208-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordano P. 1995Angiosperm fleshy fruits and seed dispersers: a comparative analysis of adaptation and constraints in plant–animal interactions. Am. Nat. 145, 163-191. ( 10.1086/285735) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman CA, Bonnell TR, Gogarten JF, Lambert JE, Omeja PA, Twinomugisha D, Wasserman MD, Rothman JM. 2013Are primates ecosystem engineers? Int. J. Primatol. 34, 1-14. ( 10.1007/s10764-012-9645-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrera CM. 1989Frugivory and seed dispersal by carnivorous mammals, and associated fruit characteristics, in undisturbed Mediterranean habitats. Oikos 55, 250-262. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valenta K, Nevo O. 2020The dispersal syndrome hypothesis: how animals shaped fruit traits, and how they did not. Funct. Ecol. 34, 1158-1169. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.13564) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady C. 1987Fruit ripening. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 38, 155-178. ( 10.1146/annurev.pp.38.060187.001103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lelievre J-M, Latche A, Jones B, Bouzayen M, Pech J-C. 1997Ethylene and fruit ripening. Physiol. Plant. 101, 727-739. ( 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1997.1010408.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath P, Bouzayen M, Mattoo AK, Claude Pech J (eds). 2014. Fruit ripening: physiology, signalling and genomics. Boston, MA: CABI. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakshi A, Shemansky JM, Chang C, Binder BM. 2015History of research on the plant hormone ethylene. J. Plant Growth Regul. 34, 809-827. ( 10.1007/s00344-015-9522-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redenbaugh K, Hiatt W, Martineau B, Emlay D. 1994Regulatory assessment of the FLAVR SAVR tomato. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 5, 105-110. ( 10.1016/0924-2244(94)90197-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janzen DH. 1983Physiological ecology of fruits and their seeds. Physiological plant ecology III , pp. 626–655. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenta K, Kalbitzer U, Razafimandimby D, Omeja P, Ayasse M, Chapman CA, Nevo O. 2018The evolution of fruit colour: phylogeny, abiotic factors and the role of mutualists. Sci. Rep. 8, 1-8. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-32604-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomáscolo SB, Schaefer HM. 2010Signal convergence in fruits: a result of selection by frugivores? J. Evol. Biol. 23, 614-624. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.01931.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duan Q, Quan RC. 2013The effect of color on fruit selection in six tropical Asian birds. Condor 115, 623-629. ( 10.1525/cond.2013.120111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu GA, et al. 2014Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 656-662. ( 10.1038/nbt.2906) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin SW, Shaw J, Haberle R, Wen J, Potter D. 2014Diversification of almonds, peaches, plums and cherries—molecular systematics and biogeographic history of Prunus (Rosaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 76, 34-48. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole T, Hilger H, Stevens P. 2019Angiosperm phylogeny poster (APP)—flowering plant systematics. PeerJ Prepr. 7, e2320v5. ( 10.7287/peerj.preprints.2320) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim TK. 2016Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poulsen JR, Clark CJ, Connor EF, Smith TB. 2002Differential resource use by primates and hornbills: implications for seed dispersal. Ecology 83, 228-240. ( 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0228:DRUBPA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forrestel EJ, Ackerly DD, Emery NC. 2015The joint evolution of traits and habitat: leaf morphology and weland habitat specialization in Lasthenia. New Phytol. 208, 949-959. ( 10.1111/nph.13478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry CS, Giovannoni JJ. 2007Ethylene and fruit ripening. J. Plant Growth Regul. 26, 143-159. ( 10.1007/s00344-007-9002-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez del Rio C, Stevens B. 1989Physiological constraint on feeding behavior: intestinal membrane disaccharidases of the starling. Science 243, 794-796. ( 10.1126/science.2916126) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer HM. 2011Why fruits go to the dark side. Acta Oecol. 37, 604-610. ( 10.1016/j.actao.2011.04.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Ma Y, Dong C, Terry LA, Watkins CB, Yu Z, Cheng Z. 2020Meta-analysis of the effects of 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) treatment on climacteric fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 7, 208. ( 10.1038/s41438-020-00405-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatsuki M, Nakajima N, Fujii H, Shimada T, Nakano M, Hayashi KI, Hayama H, Yoshioka H, Nakamura Y. 2013Increased levels of IAA are required for system 2 ethylene synthesis causing fruit softening in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch). J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1049-1059. ( 10.1093/jxb/ers381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saftner RA, Baldi BG. 1990Polyamine levels and tomato fruit development: possible interaction with ethylene. Plant Physiol. 92, 547-550. ( 10.1104/pp.92.2.547) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight RS, Siegfried WR. 1983Inter-relationships between type, size and colour of fruits and dispersal in southern African trees. Oecologia 56, 405-412. ( 10.1007/BF00379720) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patrick D, Manakadan R, Ganesh T. 2015Frugivory and seed dispersal by birds and mammals in the coastal tropical dry evergreen forests of southern India: a review. Trop. Ecol. 56, 41-55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amico GC, Rodriguez-Cabal MA, Aizen MA. 2011Geographic variation in fruit colour is associated with contrasting seed disperser assemblages in a south-Andean mistletoe. Ecography 34, 318-326. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06459.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data were uploaded as electronic supplementary material, tables S1–S4.