Abstract

Sexual selection is often considered as a critical evolutionary force promoting sexual size dimorphism (SSD) in animals. However, empirical evidence for a positive relationship between sexual selection on males and male-biased SSD received mixed support depending on the studied taxonomic group and on the method used to quantify sexual selection. Here, we present a meta-analytic approach accounting for phylogenetic non-independence to test how standardized metrics of the opportunity and strength of pre-copulatory sexual selection relate to SSD across a broad range of animal taxa comprising up to 95 effect sizes from 59 species. We found that SSD based on length measurements was correlated with the sex difference in the opportunity for sexual selection but showed a weak and statistically non-significant relationship with the sex difference in the Bateman gradient. These findings suggest that pre-copulatory sexual selection plays a limited role for the evolution of SSD in a broad phylogenetic context.

Keywords: Bateman gradient, body size, body weight, opportunity for selection, sexual selection, sexual size dimorphism

1. Introduction

Females and males often show striking differences in morphological, behavioural and physiological traits. Understanding the evolutionary drivers for this diversity is at the heart of sexual selection research [1]. One of the best-studied sex differences is dimorphism in body size, which can be found in animals along a broad continuous spectrum ranging from extremely female-biased (e.g. spiders; [2]) towards extremely male-biased dimorphism (e.g. elephant seals; [3]). Theory predicts that sex differences such as sexual size dimorphism (hereafter SSD) evolve in response to sex differences in the strength of sexual selection [4], defined as selection arising from competition for mating partners and/or their gametes [5]. More specifically, body size can be sexually selected if a bigger individual has a selective advantage during pre- and/or post-copulatory episodes of mate competition and mate choice [6]. In addition, body size often shows an allometric relationship with other sexually selected traits such as pre-copulatory ornaments and armaments but may also be tied to determinants of post-copulatory success such as gonad and gamete size [7], which may impose indirect sexual selection on body size.

Sexual selection on body size may shift the evolutionary optimum of the sex under stronger competition away from the optimum of the other sex, which manifests in intra-locus sexual conflict and can eventually be resolved in terms of sexual dimorphism [8,9]. However, the primordial effects of anisogamy and sexual selection on the evolution of sexual dimorphism can be altered by sex-specific selection on traits that affect the competition for resources other than mates. This so-called ecological character displacement has been argued to be key for a complete understanding of sexual dimorphism in a variety of traits, including feeding morphology, habitat use and especially body size [10]. Therefore, both sexual and natural selection may contribute to the evolution of SSD and potentially in opposing ways [11].

There is compelling evidence from numerous comparative studies suggesting that sexual selection indeed plays an important role for the evolution of SSD in many animal taxa including insects [12], fishes [13], birds [14], reptiles [15] and mammals [16]. However, for many of those taxa, there are also comparative studies that failed to demonstrate a relationship between sexual selection and SSD [17–19] or conclude that sexual selection plays only a minor role in shaping size differences between males and females [20]. These inconsistencies may arise from differences within tested clades but may also stem from difficulties in quantifying the strength and direction of sexual selection in a meaningful way allowing interspecific comparisons. In fact, most studies use categorical variables to describe interspecific variation in sexual selection such as mating system or male combat, which often do not capture the entire variation in the strength of sexual selection. Moreover, many studies use proxies that can only measure sexual selection in males (e.g. of harem size, testis size, male territoriality) assuming that competition for mates is absent or rare in females, which might often be an oversimplification [21].

Here, we aim to expand our knowledge on the evolution of SSD by testing its relationship with standardized metrics of sex-specific sexual selection derived from Bateman's principles [22]. Specifically, we use a phylogenetic meta-analysis to explore how SSD relates to sex differences in both the opportunity for sexual selection and the Bateman gradient across a broad range of animal taxa. The opportunity for sexual selection (Is) is defined as the variance in relativized mating success, which provides an upper limit for mate monopolization and, therefore, for the intensity of pre-copulatory competition for mating partners in a population [23,24]. The Bateman gradient (βss) represents the slope of a linear regression of reproductive success on mating success and provides an upper limit of pre-copulatory sexual selection on a phenotypic trait [25]. Both metrics have been argued to provide reliable and complementary measures for the strength of sexual selection [26,27]. If sexual selection drives SSD, we expect the sex with the steeper βss and the higher Is to be bigger relative to the other.

2. Methods

(a) . Data acquisition

We extracted published estimates of the strength of sexual selection following a search protocol described in more detail elsewhere [28]. In brief, we conducted a systematic literature search using the ISI Web of Knowledge (Web of Science Core Collection, from 1900 to 2020) with the ‘topic’ search terms defined as (‘Bateman*’ OR ‘opportunit* for selection’ OR ‘opportunit* for sexual selection’ OR ‘selection gradient*’). All primary articles were screened for studies reporting both male and female estimates for Is or βss. We used a database updated on the 30 November 2020 [29] encompassing 86 estimates of Is and 95 estimates of βss from a total of 65 studies (electronic supplementary material, table S1; for PRISMA diagram see electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

In order to estimate SSD for all sampled species, we extracted estimates of male and female size from the literature (electronic supplementary material, table S2). When the relevant data were not reported in the text, we extracted estimates from published figures by using the metaDigitise R package v. 1.0.1 [30]. We estimated SSD separately for both length and weight data because both traits have been argued to be meaningful measures to quantify SSD. Length often shows high repeatability and may better reflect overall body size, whereas weight is considered a more labile trait but may better reflect physical strength of an individual [31]. Hence, both measures provide complementary measures to estimate SSD. Length data were obtained from 53 species based on measurements of body length (N = 27), wing length (N = 9), snout-to-vent length (N = 8), elytra length (N = 5) and thorax length (N = 4). Bodyweight data were obtained from 42 species. For species for which we could not retrieve length (N = 6) or bodyweight data (N = 17), we converted length into weight estimates (or vice versa) using published formulae of allometric relationships (electronic supplementary material, table S3).

We then computed SSD as

with positive or negative values indicating species with males or females being the larger sex, respectively. Estimates of SSD based on length and weight were highly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.88, p < 0.001, N = 58). An alternative metric proposed by Lovich & Gibbons [32] is often used in studies of SSD and sexual selection showing very similar statistical properties as the ln ratio [33]. For completeness, we present results using the Lovich and Gibbons ratio in the electronic supplementary material.

(b) . Phylogenetic affinities

To account for phylogenetic non-independence, we reconstructed the phylogeny of all sampled species using divergence times from the TimeTree database (http://www.timetree.org/; [34]). The obtained distance matrix was then transformed into the NEWICK format using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean algorithm implemented in MEGA (https://www.megasoftware.net/; [35]). In total, our dataset included 59 species from a broad range of animal taxa with a majority of arthropods (NSpecies = 16), birds (NSpecies = 13), fishes (NSpecies = 8) and mammals (NSpecies = 8) (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

(c) . Statistical analysis

We computed effect sizes of the sex difference in Is or βss as described by Janicke et al. [28]. In particular, we used the natural logarithm of the ratio between male and female coefficients of variation in mating success (lnCVR; [36]) as an effect size for the sex difference in the opportunity for sexual selection (ΔIs). Moreover, we computed Hedges' g [37] by subtracting the female from the male Bateman gradient, in order to obtain an effect size for the sex difference in the Bateman gradient (Δβss). Hence, positive values of ΔIs and Δβss indicate a male bias in the opportunity and the strength of sexual selection, respectively.

We tested for a relationship between SSD and sex-specific sexual selection by running linear mixed effects models (LMMs) using the rma.mv function implemented in the metafor R package v. 2.4-0 [38]. In particular, we defined the effect size (ΔIs or Δβss) as a response variable weighted by the inverse of its sampling variance and included SSD as the only fixed predictor variable. In all models, we included observation identifier, study identifier, species identifier and the phylogenetic correlation matrix as random terms. Heterogeneity (I2) was estimated as the proportional variance explained by each random term, where I2Phylogeny corresponds to the phylogenetic signal (also termed phylogenetic heritability) [39]. Goodness of fit was quantified using McFadden's R2 [40].

We ran LMMs on a complete dataset including all sampled species and on subsets including only vertebrates or invertebrates in order to provide a taxonomically more nuanced test on the relationship between sexual selection and SSD. Outlier analysis for estimates of SSD of the complete dataset revealed that one of the sampled species (Latrodectus hasseltii) has an extremely female-biased SSD when using both length and weight measurements (Grubb's test of SSDLength: G = 6.394, p < 0.001) and was, therefore, excluded from all analyses. Thus, LMMs testing for a relationship between SSD and sexual selection metrics comprised 58 species. In addition, outlier analysis of SSD of the invertebrate data detected an additional outlier (i.e. Paracerceis sculpta; Grubb's test of SSDLength G = 3.582, p < 0.001), which was excluded from statistical analyses on invertebrates. Note that exclusion of both species did not lead to qualitative changes of model results.

We used Kendell's rank correlation test to quantify funnel plot asymmetry, which can be indicative of publication bias. In addition, we tested for potential publication bias by running LMMs as described above with the sampling variance of the given effect size as the only predictor variable. Residuals of all models were checked for normality by visual inspection of quantile–quantile plots. All statistical analyses were carried out in R v. 4.0.3 [41].

3. Results

We found evidence for stronger sexual selection on males as indicated by a positive global effect size of ΔIs (phylogenetic LMM with no predictor variables: N = 86, estimate ± s.e. = 0.282 ± 0.077, z-value = 3.676, p < 0.001) and Δβss (N = 94, estimate ± s.e. = 0.441 ± 0.114, z-value = 3.876, p < 0.001) echoing previous findings [28].

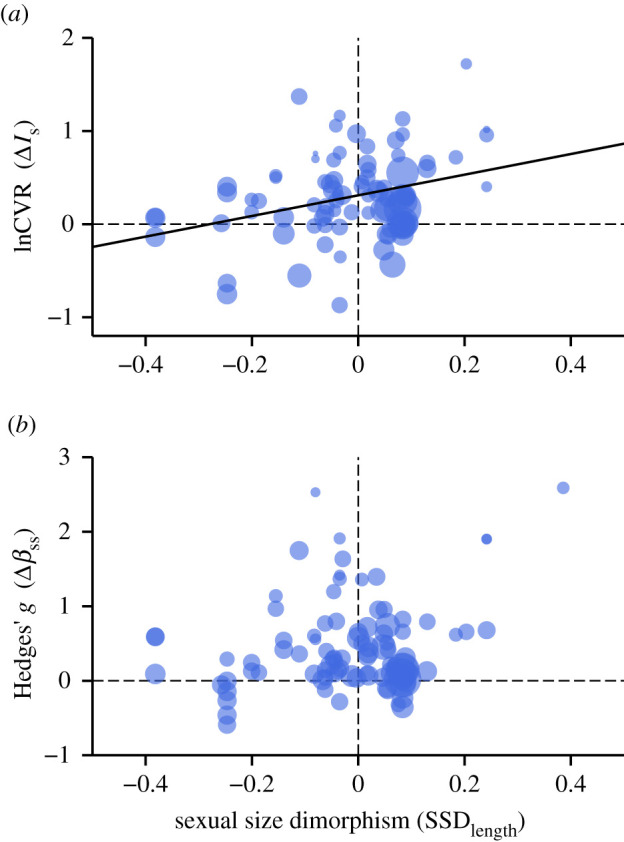

Importantly, we detected a positive relationship between SSDLength and ΔIs together with a statistically non-significant trend for an also positive relationship between SSDLength and Δβss (figure 1 and table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S4). Effects of SSDWeight on ΔIs and Δβss were also positive but statistically non-significant (table 1). Moreover, there was no significant relationship when invertebrates or vertebrates were considered separately (table 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between sexual size dimorphism (SDDLength) and sexual selection quantified in terms of (a) the sex difference in the opportunity for sexual selection (ΔIs) and (b) the sex difference in the Bateman gradient (Δβss). Positive values in SDDLength, ΔIs and Δβss indicate a male bias.

Table 1.

Model summaries of phylogenetic meta-analyses testing for the relationship between sexual size dimorphism (SSD) and standardized metrics of sexual selection. Sexual size dimorphism is defined as SSD = ln((male trait value)/(female trait value)) where trait is either length or weight. Sexual selection is quantified as the sex difference in the opportunity for sexual selection (ΔIs) and the Bateman gradient (Δβss). Estimates of heterogeneity (I2) are shown for variance arising from observation, study, species and phylogeny. The proportional variance explained by SSD is given as Fadden's R2. Model outcomes are presented for analyses including all sampled taxa and separately for vertebrates and invertebrates.

| response | model | N | estimate ± s.e. | z-value | p-value | I2Observation | I2Study | I2Species | I2Phylogeny | Fadden's R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model summaries for SSDLength | ||||||||||

| ΔIs | all taxa | 86 | 1.14 ± 0.46 | 2.48 | 0.013 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.09 |

| vertebrates | 63 | 1.02 ± 0.55 | 1.87 | 0.062 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.09 | |

| invertebrates | 19 | 0.87 ± 1.01 | 0.86 | 0.388 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.05 | |

| Δβss | all taxa | 94 | 0.97 ± 0.52 | 1.85 | 0.064 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| vertebrates | 71 | 0.53 ± 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.362 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.02 | |

| invertebrates | 22 | −0.86 ± 1.42 | −0.61 | 0.544 | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

| model summaries for SSDWeight | ||||||||||

| ΔIs | all taxa | 86 | 0.40 ± 0.21 | 1.86 | 0.063 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.02 |

| vertebrates | 63 | 0.15 ± 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.564 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.02 | |

| invertebrates | 19 | 0.25 ± 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.456 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

| Δβss | all taxa | 94 | 0.29 ± 0.24 | 1.21 | 0.226 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.01 |

| vertebrates | 71 | −0.04 ± 0.27 | −0.16 | 0.872 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.01 | |

| invertebrates | 22 | −0.31 ± 0.49 | −0.63 | 0.528 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

We detected signs of funnel plot asymmetry (electronic supplementary material, figure S3) for ΔIs (Kendall's τ = 0.274, p < 0.001) and Δβss (Kendall's τ = 0.222, p < 0.001) with an underrepresentation of studies of low precision and a negative effect-size (i.e. stronger sexual selection in females). This finding is backed by phylogenetic LMMs in which the sampling variance of the effect size is defined as the only predictor variable (ΔIs: N = 86, estimate ± s.e. = 1.733 ± 0.818, z-value = 2.112, p = 0.034; Δβss: N = 94, estimate ± s.e. = 3.945 ± 0.719, z-value = 5.485, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study provides, to our knowledge, the first test of an evolutionary link between standardized metrics of the strength of sexual selection and SSD across a broad phylogenetic range covering vertebrate and invertebrate taxa. We found mixed support for the hypothesis that sexual selection is the main driver of the evolution of SSD. Specifically, SSDLength was correlated with ΔIs but showed no statistically significant relationship with Δβss. As predicted, species with male-biased SSDLength showed a higher Is in males relative to females. This suggests that a highly skewed mating success towards bigger males may indeed promote the evolution of bigger males. However, the observed effect was weak with SSDLength explaining only 9% of the variance in ΔIs (equivalent to an effect size of r = 0.3). Besides, we did not detect a significant relationship between SSD and Is when body size was inferred from body weight. In a previous study, Soulsbury et al. [42] tested for a relationship between the Is and SSD reporting evidence for a relationship in mammals but not in birds. However, their analysis was loaded primarily by estimates of the opportunity for selection (i.e. variance in reproductive success; I) rather than Is, which makes their findings difficult to interpret especially because estimates of I do not only capture the opportunity for sexual but also for natural selection [27]. Moreover, their study included only estimates of I and Is of males assuming that sexual selection on body size can be neglected in females, which might often be an incorrect assumption [21].

Contrary to our findings on ΔIs, we did not detect a significant relationship between SSD and Δβss suggesting that sex-specific selection on body size is not primarily mediated by sex differences in pre-copulatory sexual selection. These contrasting results may reflect differences in the properties of Is and βss, with the former providing a measure for the potential of intra-sexual competition for mates, whereas the latter quantifies the benefit of succeeding in mate acquisition [27]. Nevertheless, given that βss constitutes a proxy for the upper potential of pre-copulatory sexual selection on body size [23], we would have predicted an effect on Δβss if sexual selection was a strong determinant of SSD in animals.

The absence of a strong relationship between SSD and sexual selection may reflect a weak evolutionary causal link between both and/or may stem from methodological limitations of our study. First, sexual selection may often not target body size because intra-sexual competition does not necessarily manifest in physical fighting, which might especially be true for many invertebrates that show scramble competition for mating partners [43]. Second, competition for mates and mate choice may not only impose directional positive selection on body size. For instance, in birds, sexual selection has been argued to favour small males allowing them to be more agile in sexually selected aerial displays [14]. Finally, sexual selection for larger individuals in the competing sex (typically males) may not necessarily be stronger than fecundity selection on body size in the other sex (typically females), which implies that sex differences in sexual selection alone may not predict the evolution of SSD. For these reasons, the lack of a relationship between sexual selection and SSD might not be surprising especially when tested across a broad taxonomic range.

In terms of methodological limitations, both proxies of sexual selection used in this study have been argued to be particularly powerful in comparative studies [26,27], but like other proxies they also have downsides. Notably, Is and βss measure the potential and strength of pre-copulatory sexual selection. This might be especially problematic for the male sex, in which sexual selection on body size can also operate along post-copulatory episodes because bigger individuals can be better sperm competitors [44]. Presumably, the most powerful approach to test for an evolutionary link between sexual selection and SSD across species involves mating- and post-mating differentials of body size for both sexes [23]. We presume that this kind of data are currently available for only a few species but might become available in the future to be subjected to a broad-scale meta-analysis.

Collectively, our study provides limited evidence for the hypothesis that sexual selection promotes SSD when tested across a broad phylogenetic context. Despite our finding of a positive relationship between ΔIs and SSD, its explanatory power was low suggesting that sexual selection plays only a minor role in the evolution of SSD. Moreover, our results echo the body of previous comparative studies indicating that evidence for an effect of sexual selection and SSD depends on the proxy used to quantify sexual selection. For these reasons, our study challenges the common practice of using SSD as a proxy for sexual selection [45–47]. We conclude that despite compelling evidence for SSD to correlate with sexual selection within some animal clades, it appears to be a poor predictor for pre-copulatory sexual selection at a broader taxonomic scale. Alternative mechanisms such as ecological character displacement may be crucial to understand the full diversity of SSD in animals.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the authors of all primary studies for making their research accessible. We also thank Tamás Székely for discussions and three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments.

Data accessibility

The data are available in the Dryad Digital Repository at https://datadryad.org/ and can be accessed through the DOI https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7d7wm37vv [48].

Additional information is provided in the electronic supplementary material [49].

Authors' contributions

T.J. conceived the study and designed the meta-analysis. S.F. and T.J. collected the data. T.J. performed the statistical analyses and wrote the paper with the help from S.F. All authors approve the final version and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG grant no.: JA 2653/2-1) and the CNRS.

References

- 1.Andersson M. 1994Sexual selection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foellmer MW, Moya-Larano J. 2007Sexual size dimorphism in spiders: patterns and processes. In Sex, size and gender roles: evolutionary studies of sexual size dimorphism (eds DJ Fairbairn, WU Blanckenhorn, T Székely), pp. 71-81. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindenfors P, Tullberg BS, Biuw M. 2002Phylogenetic analyses of sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in pinnipeds. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 52, 188-193. ( 10.1007/s00265-002-0507-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schärer L, Rowe L, Arnqvist G. 2012Anisogamy, chance and the evolution of sex roles. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 260-264. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2011.12.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shuker DM. 2010Sexual selection: endless forms or tangled bank? Anim. Behav. 79, E11-E17. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.10.031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson M, lwasa Y. 1996Sexual selection. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 53-58. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81042-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lüpold S, Manier MK, Puniamoorthy N, Schoff C, Starmer WT, Luepold SHB, Belote JM, Pitnick S. 2016How sexual selection can drive the evolution of costly sperm ornamentation. Nature 533, 535-538. ( 10.1038/nature18005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lande R. 1980Sexual dimorphism, sexual selection, and adaptation in polygenic characters. Evolution 34, 292-305. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04817.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeve JP, Fairbairn DJ. 2001Predicting the evolution of sexual size dimorphism. J. Evol. Biol. 14, 244-254. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00276.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Lisle SP. 2019Understanding the evolution of ecological sex differences: integrating character displacement and the Darwin–Bateman paradigm. Evol. Lett. 3, 434-447. ( 10.1002/evl3.134) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbairn DJ, Blanckenhorn WU, Székely T. 2007Sex, size and gender roles: evolutionary studies of sexual size dimorphism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serrano-Meneses MA, Cordoba-Aguilar A, Azpilicueta-Amorin M, Gonzalez-Soriano E, Szekely T. 2008Sexual selection, sexual size dimorphism and Rensch's rule in Odonata. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1259-1273. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01567.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyron M, Pitcher TE, Jacquemin SJ. 2013Evolution of mating systems and sexual size dimorphism in North American cyprinids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 67, 747-756. ( 10.1007/s00265-013-1498-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szekely T, Lislevand T, Figuerola J. 2007Sexual size dimorphism in birds. In Sex, size and gender roles: evolutionary studies of sexual size dimorphism (eds Fairbairn DJ, Blanckenhorn WU, Székely T), pp. 27-37. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shine R. 1994Sexual size dimorphism in snakes revisited. Copeia 1994, 326-346. ( 10.2307/1446982) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassini MH. 2020Sexual size dimorphism and sexual selection in primates. Mammal Rev. 50, 231-239. ( 10.1111/mam.12191) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figuerola J, Green AJ. 2000The evolution of sexual dimorphism in relation to mating patterns, cavity nesting, insularity and sympatry in the Anseriformes. Funct. Ecol. 14, 701-710. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2000.00474.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pincheira-Donoso D, Harvey LP, Grattarola F, Jara M, Cotter SC, Tregenza T, Hodgson DJ. 2021The multiple origins of sexual size dimorphism in global amphibians. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 443-458. ( 10.1111/geb.13230) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kratochvil L, Frynta D. 2002Body size, male combat and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in eublepharid geckos (Squamata: Eublepharidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 76, 303-314. ( 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00064.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox RM, Skelly SL, John-Alder HB. 2003A comparative test of adaptive hypotheses for sexual size dimorphism in lizards. Evolution 57, 1653-1669. ( 10.1554/02-227) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hare RM, Simmons LW. 2019Sexual selection and its evolutionary consequences in female animals. Biol. Rev. 94, 929-956. ( 10.1111/brv.12484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman AJ. 1948Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2, 349-368. ( 10.1038/hdy.1948.21) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones AG. 2009On the opportunity for sexual selection, the Bateman gradient and the maximum intensity of sexual selection. Evolution 63, 1673-1684. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00664.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janicke T, Morrow EH. 2018Operational sex ratio predicts the opportunity and direction of sexual selection across animals. Ecol. Lett. 21, 384-391. ( 10.1111/ele.12907) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold SJ. 1994Bateman principles and the measurement of sexual selection in plants and animals. Am. Nat. 144, S126-S149. ( 10.1086/285656) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anthes N, Häderer IK, Michiels NK, Janicke T. 2017Measuring and interpreting sexual selection metrics—evaluation and guidelines. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 918-931. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12707) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mobley KB. 2014Mating systems and the measurement of sexual selection. In Animal behaviour: how and why animals do the things they do (eds Yasukawa K), pp. 99-144. Santa Barbara, New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janicke T, Häderer IK, Lajeunesse MJ, Anthes N. 2016Darwinian sex roles confirmed across the animal kingdom. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500983. ( 10.1126/sciadv.1500983) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fromonteil S, Winkler L, Marie-Orleach L, Janicke T. 2021Sexual selection in females across the animal tree of life. bioRxiv. ( 10.1101/2021.05.25.445581) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Pick JL, Nakagawa S, Noble DW. 2019Reproducible, flexible and high-throughput data extraction from primary literature: the metaDigitise r package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 426-431. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.13118) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairbairn D. 2007Introduction: the enigma of sexual size dimorphism. In Sex, size and gender roles. Evolutionary studies of sexual dimorphism (eds Fairbairn DJ, Blanckenhorn WUSzekely T), pp. 1-15. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovich JE, Gibbons JW. 1992A review of techniques for quantifying sexual size dimorphism. Growth Dev. Aging 56, 269-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith RJ. 1999Statistics of sexual size dimorphism. J. Hum. Evol. 36, 423-458. ( 10.1006/jhev.1998.0281) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. 2017TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812-1819. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547-1549. ( 10.1093/molbev/msy096) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagawa S, Poulin R, Mengersen K, Reinhold K, Engqvist L, Lagisz M, Senior AM. 2015Meta-analysis of variation: ecological and evolutionary applications and beyond. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 143-152. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12309) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. 2009Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viechtbauer W. 2010Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v036.i03) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Villemereuil P, Nakagawa S. 2014General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology. In Modern phylogenetic comparative methods and their application in evolutionary biology (ed. Garamszegi LZ), pp. 287-303. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. 2012Biometry: the principles and practise of statistics in biological research, 4th edn. New York, CA: W. H. Freeman and Co. [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Core Team. 2020A language and environment for statistical computing. 4.0.3 ed. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. See http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soulsbury CD, Kervinen M, Lebigre C. 2014Sexual size dimorphism and the strength of sexual selection in mammals and birds. Evol. Ecol. Res. 16, 63-76. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fairbairn DJ, Preziosi RF. 1994Sexual selection and the evolution of allometry for sexual size dimorphism in the water strider, Aquarius remigis. Am. Nat. 144, 101-118. ( 10.1086/285663) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pélissié B, Jarne P, David P. 2014Disentangling precopulatory and postcopulatory sexual selection in polyandrous species. Evolution 68, 1320-1331. ( 10.1111/evo.12353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahrl AF, Cox CL, Cox RM. 2016Correlated evolution between targets of pre- and postcopulatory sexual selection across squamate reptiles. Ecol. Evol. 6, 6452-6459. ( 10.1002/ece3.2344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikula P, Valcu M, Brumm H, Bulla M, Forstmeier W, Petruskova T, Kempenaers B, Albrecht T. 2021A global analysis of song frequency in passerines provides no support for the acoustic adaptation hypothesis but suggests a role for sexual selection. Ecol. Lett. 24, 477-486. ( 10.1111/ele.13662) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen IP, Stuart-Fox D, Hugall AF, Symonds MRE. 2012Sexual selection and the evolution of complex color patterns in dragon lizards. Evolution 66, 3605-3614. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01698.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janicke T, Fromonteil S. 2021Data from: Sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in animals. Dryad Digital Repository ( 10.5061/dryad.7d7wm37vv) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Janicke T, Fromonteil S. 2021Sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in animals. FigShare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Janicke T, Fromonteil S. 2021Data from: Sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in animals. Dryad Digital Repository ( 10.5061/dryad.7d7wm37vv) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Janicke T, Fromonteil S. 2021Sexual selection and sexual size dimorphism in animals. FigShare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in the Dryad Digital Repository at https://datadryad.org/ and can be accessed through the DOI https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7d7wm37vv [48].

Additional information is provided in the electronic supplementary material [49].