Abstract

Background

Health services have traditionally been developed to focus on specific diseases or medical specialties. Involving consumers as partners in planning, delivering and evaluating health services may lead to services that are person‐centred and so better able to meet the needs of and provide care for individuals. Globally, governments recommend consumer involvement in healthcare decision‐making at the systems level, as a strategy for promoting person‐centred health services. However, the effects of this 'working in partnership' approach to healthcare decision‐making are unclear. Working in partnership is defined here as collaborative relationships between at least one consumer and health provider, meeting jointly and regularly in formal group formats, to equally contribute to and collaborate on health service‐related decision‐making in real time. In this review, the terms 'consumer' and 'health provider' refer to partnership participants, and 'health service user' and 'health service provider' refer to trial participants.

This review of effects of partnership interventions was undertaken concurrently with a Cochrane Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (QES) entitled Consumers and health providers working in partnership for the promotion of person‐centred health services: a co‐produced qualitative evidence synthesis.

Objectives

To assess the effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership, as an intervention to promote person‐centred health services.

Search methods

We searched the CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases from 2000 to April 2019; PROQUEST Dissertations and Theses Global from 2016 to April 2019; and grey literature and online trial registries from 2000 until September 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, and cluster‐RCTs of ‘working in partnership’ interventions meeting these three criteria: both consumer and provider participants meet; they meet jointly and regularly in formal group formats; and they make actual decisions that relate to the person‐centredness of health service(s).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened most titles and abstracts. One review author screened a subset of titles and abstracts (i.e. those identified through clinical trials registries searches, those classified by the Cochrane RCT Classifier as unlikely to be an RCT, and those identified through other sources). Two review authors independently screened all full texts of potentially eligible articles for inclusion. In case of disagreement, they consulted a third review author to reach consensus. One review author extracted data and assessed risk of bias for all included studies and a second review author independently cross‐checked all data and assessments. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion, or by consulting a third review author to reach consensus. Meta‐analysis was not possible due to the small number of included trials and their heterogeneity; we synthesised results descriptively by comparison and outcome. We reported the following outcomes in GRADE ‘Summary of findings’ tables: health service alterations; the degree to which changed service reflects health service user priorities; health service users' ratings of health service performance; health service users' health service utilisation patterns; resources associated with the decision‐making process; resources associated with implementing decisions; and adverse events.

Main results

We included five trials (one RCT and four cluster‐RCTs), with 16,257 health service users and more than 469 health service providers as trial participants. For two trials, the aims of the partnerships were to directly improve the person‐centredness of health services (via health service planning, and discharge co‐ordination). In the remaining trials, the aims were indirect (training first‐year medical doctors on patient safety) or broader in focus (which could include person‐centredness of health services that targeted the public/community, households or health service delivery to improve maternal and neonatal mortality). Three trials were conducted in high income‐countries, one was in a middle‐income country and one was in a low‐income country. Two studies evaluated working in partnership interventions, compared to usual practice without partnership (Comparison 1); and three studies evaluated working in partnership as part of a multi‐component intervention, compared to the same intervention without partnership (Comparison 2). No studies evaluated one form of working in partnership compared to another (Comparison 3).

The effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership compared to usual practice without partnership are uncertain: only one of the two studies that assessed this comparison measured health service alteration outcomes, and data were not usable, as only intervention group data were reported. Additionally, none of the included studies evaluating this comparison measured the other primary or secondary outcomes we sought for the 'Summary of findings' table.

We are also unsure about the effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership as part of a multi‐component intervention compared to the same intervention without partnership. Very low‐certainty evidence indicated there may be little or no difference on health service alterations or health service user health service performance ratings (two studies); or on health service user health service utilisation patterns and adverse events (one study each). No studies evaluating this comparison reported the degree to which health service alterations reflect health service user priorities, or resource use.

Overall, our confidence in the findings about the effects of working in partnership interventions was very low due to indirectness, imprecision and publication bias, and serious concerns about risk of selection bias; performance bias, detection bias and reporting bias in most studies.

Authors' conclusions

The effects of consumers and providers working in partnership as an intervention, or as part of a multi‐component intervention, are uncertain, due to a lack of high‐quality evidence and/or due to a lack of studies. Further well‐designed RCTs with a clear focus on assessing outcomes directly related to partnerships for patient‐centred health services are needed in this area, which may also benefit from mixed‐methods and qualitative research to build the evidence base.

Keywords: Humans; Infant, Newborn; Delivery of Health Care; Family; Health Services; Infant Mortality; Patient Safety

Plain language summary

When healthcare consumers (patients, carers and family members) and healthcare providers work together as partners to plan, deliver and evaluate health services, what effects does this have?

What are person‐centred health services?

Traditionally, health services have been developed by healthcare providers and focus on specific diseases or medical specialties. Involving consumers as partners in planning, delivering and evaluating health services may lead to services that are better able to meet the needs of and provide care for individuals.

Why we did this Cochrane review

Governments worldwide recommend that healthcare providers work with consumers to promote person‐centred health services. However, the effects of healthcare providers and consumers working together are unclear.

We reviewed the evidence from research studies to find out about the effects of healthcare providers and consumers working together to plan, deliver and evaluate health services.

Specifically, we wanted to know if consumers and healthcare providers working together in partnership – in the form of regular meetings in which consumers and providers were invited to contribute as equals to decisions about health services – had an impact on:

‐ changes to health services;

‐ the extent to which changes to health services reflected service users’ priorities;

‐ users’ ratings of health services;

‐ health service use; and

‐ time and money needed to make or act on decisions about health services.

We also wanted to find out if there were any unwanted (adverse) effects.

What did we do?

First, we searched the medical literature for studies that compared:

‐ consumers and healthcare providers working in partnership against usual practice or other strategies with no partnership; or

‐ different ways of working in partnership (for example, with fewer or more consumers, or with online or face‐to‐face meetings).

We then compared the results, and summarised the evidence from all the studies. Finally, we rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes, and the consistency of findings across studies.

What did we find?

We found five studies that involved a total of 16,257 health service users and more than 469 health service providers. Three studies took place in high income‐countries and one each in middle‐ and low‐income countries.

The studies compared:

‐ working in partnership against usual practice without partnership working (2 studies); and

‐ working in partnership as part of a wider strategy to promote person‐centred health services, against the same wider strategy without partnership working (3 studies).

No studies evaluated one form of working in partnership compared to another.

What are the main results of our review?

The studies provided insufficient evidence to determine if working in partnership had any effects compared to usual practice or wider strategies with no working in partnership.

No studies investigated:

‐ impacts on the extent to which changes to health services reflected service users’ priorities, or

‐ the resources needed to make or act on decisions about health services.

Few studies investigated:

‐ impacts on changes to health services;

‐ users’ ratings of health services;

‐ health service use; and

‐ adverse events.

The few studies that did investigate these outcomes either did not report usable information or produced findings in which we have very little confidence. These studies were small, used methods likely to introduce errors in their results and focused on specific settings or populations. Their results are unlikely to reflect the results of all the studies that have been conducted in this area, some of which have not made their results public yet.

What does this mean?

There is not enough robust evidence to determine the effects of consumers and providers working in partnership to plan, deliver or evaluate health services.

This review highlights the need for well‐designed studies with a clear focus on evaluating the effects of partnerships for promoting person‐centred care in health services. This area of research may also benefit from studies that investigate why certain partnerships between consumers and healthcare providers may be more successful than others, and an accompanying qualitative evidence synthesis addressing this aspect is forthcoming.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to April 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Consumers and providers working in partnership compared with usual practice.

| Comparison 1 | |||

|

Patients or population: consumer and provider partnership participants or trial participants Settings: community, policy, teaching or health care setting Intervention: working in partnership Comparison: usual practice | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | No. of studies | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Health service alterations (changes to services resulting from decisions) |

No studies that comparatively evaluated this outcome were found1. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Degree to which health service alterations reflect health service user (trial participant) priorities (demand responsiveness) | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health service user (trial participant) health service performance ratings (local accountability) | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health service user (trial participant) health service utilisation patterns | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Resources associated with decision‐making process | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Resources associated with implementing decisions (e.g. changed services) | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

1One study (Persson 2013) identified problems and actions taken to address these in the intervention group only.

Summary of findings 2. Multi‐component intervention with consumers and providers working in partnership compared to the same intervention without partnership.

| Comparison 2 | |||

|

Patients or population: consumer and provider partnership participants or trial participants Settings: community, policy, teaching or health care setting Intervention: multi‐component intervention that includes working in partnership Comparison: same intervention without partnership | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | No. of studies | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Health service alterations (changes to services resulting from decisions) Follow‐up: 12 months (Wu 2019) to 21 months (O'Connor 2019) |

We are uncertain about the effects of multi‐component interventions on this outcome. Two studies (862 participants) were identified, both reporting little to no difference between groups, but results could not be pooled in meta‐analysis due to differences in outcome measures. |

2 | +OOO VERY LOW a,b,c,d |

| Degree to which health service alterations reflect health service user (trial participant) priorities (demand responsiveness) | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Health service user (trial participant) health service performance ratings (local accountability) Follow‐up: 12 months (Greco 2006) to 21 months (O'Connor 2019) |

We are uncertain about the effects of multi‐component interventions on this outcome. Two studies (one randomised 792 participants, the other randomised 26 clusters with 8967 participants) were identified, both reporting little to no difference between groups, but result could not be pooled in meta‐analysis due to differences in outcome measures. |

2 | +OOO VERY LOW a,b,d |

| Health service user (trial participant) health service utilisation patterns Follow‐up: 12 months (Wu 2019) |

We are uncertain about the effects of multi‐component interventions on this outcome. One study (384 participants) reported little to no difference between groups. |

1 | +OOO VERY LOW a,b,d,e |

| Resources associated with decision‐making process | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Resources associated with implementing decisions (e.g. changed services) | No studies that evaluated this outcome were found. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adverse events Follow‐up: 12 months (Wu 2019) |

We are uncertain about the effects of multi‐component interventions on this outcome. One study (384 participants) reported that no harms were observed in either group. |

1 | +OOO VERY LOW a,b,d,e |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||

aDowngraded by one level for crucial risk of bias for multiple criteria: high or unclear for methods of sequence generation (O'Connor 2019; Wu 2019); allocation concealment (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019; Wu 2019); blinding (unclear for participants/providers/outcome assessors (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019); providers (Wu 2019); loss to follow‐up (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019); selective outcome reporting/analyses (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019; Wu 2019); and other sources of bias (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019).

bDowngraded by one level for some indirectness: compared to the review question one or more studies are restricted in setting and population (O'Connor 2019; Wu 2019).

cDowngraded by one level for some imprecision: although results were based on studies (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019) with a total number of events >300; effect sizes are small and suggest little to no effect with the intervention but include benefit or harm. One or more studies didn't explicitly define the MID for this outcome or present CIs.

dDowngraded by one level as publication bias is strongly suspected: results come from studies unlikely to be representative of the studies that have been conducted, as protocols exist for completed trials not yet published.

eDowngraded by one level for some imprecision as the total number of events is less than 300 and the optimal sample size is not clear (Wu 2019).

Background

This review assessed the effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership, as an intervention, on health services planning, delivery and evaluation. Such partnerships may lead to more person‐centred health services. In this review, we use the term 'consumer' to mean patients, their carers and family members, in recognition of the roles that different people may undertake in health care and health care planning. We define ‘working in partnership’ as consumers and health providers making decisions together, in formal group formats (such as committees, councils, boards, or steering groups), about aspects of health service planning, delivery, or evaluation (or a combination), with the aim of making health services person‐centred (see Glossary of key terms in Appendix 1). This review was conducted concurrently with a Cochrane Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (QES) entitled Consumers and health providers working in partnership for the promotion of person‐centred health services: a co‐produced qualitative evidence synthesis (Merner 2019; Figure 1).

1.

Modified infographic comparing the Intervention effects review process (on the left) and the Qualitative evidence synthesis review process (on the right (Kaufman 2011))

Description of the condition

Historical and theoretical context of working in partnership for the promotion of person‐centred care

The concept of consumers and providers working in partnerships in healthcare decision‐making is based on paradigms of recovery, empowerment, and human, democratic, or consumer rights. The mental health consumer recovery and empowerment movement explicitly utilises consumer experiential knowledge through working in partnership, to transform and innovate services and policies (Pelletier 2011). In some countries, the impetus for working in partnership in decision‐making at the health service level, in addition to the point of care level (whether consultation or encounter), has been driven by healthcare safety and quality standards and rights. For example, the Australian National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards mandate that health service organisations partner with consumers in health governance, policy, and planning to design, deliver, and evaluate healthcare systems and services (ACSQHC 2017). The Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights states that people using the Australian healthcare system have the right to participate in decision‐making and choices about their own care, and about health service planning and policies (ACSQHC 2008). Partnership with consumers at the governance level is also becoming more common internationally (National Patient Safety Foundation 2014).

Person‐centred care definition and features

Worldwide, healthcare sectors are adopting person‐centred principles to enhance quality of care, and empower consumers to participate in their care (Byrne 2020; Delaney 2018; Mockford 2012; Stone 2008; Tritter 2003). There are various definitions of person‐centred care, but there is no single, universally accepted definition (Byrne 2020), and terms such as individualised or personalised, and patient‐, family‐, or user‐centred care are conceptually similar (Greene 2012). Common to these terms and definitions is the provision of health care that emphasises personhood and partnership (Edgman‐Levitan 2013; Hubbard 2007). This review adopts the following definition of person‐centred care: ‘planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among healthcare providers, patients, and families’ (IPFCC 2012).

Person‐centred care is an overarching concept or ethos, which has often been implemented at the health service level. Its implementation may also affect interactions at the point of care in many different ways. For instance, the Picker Institute identifies the following principles for person‐centred care, which underpin interventions at point of care: respecting consumer preferences and values; providing emotional support, physical comfort, information, communication, and education; continuity and transitions, co‐ordination of, and access to care; and involvement of the family and friends (Picker Institute 1987). Person‐centred care contrasts with systems‐ or provider‐centred care, which has been criticised for being paternalistic, medically dominated, and illness‐oriented (Bardes 2012; Berwick 2009).

Working in partnership for the promotion of person‐centred health services

Working in partnership may be a key intervention for the promotion of person‐centred health services. It is the focus of this review, but it is also important to note that this is only one of several elements of person‐centred care and that other elements exist outside this review's focus. Working in partnership may impact organisational leadership, strategic vision, consumer involvement, measurement and feedback of consumer experience, staff capacity building, incentives, accountability, and a culture supportive of learning and change (Edgman‐Levitan 2013; Luxford 2011). Qualitative research has identified that factors embedded within the broader health service(s) and health system, and policies are important to facilitate person‐centred care in the consultation process (i.e. at the point of care delivery (Batalden 2016; Leyshon 2015; Ogden 2017)).

At point of care, person‐centred consultations typically have three main features: eliciting and skilfully listening to the consumer’s personal narrative; encouraging the consumer’s active participation in goal setting; and documenting goals (Moore 2017). Interventions that support one or more of these features include shared decision‐making (Legaré 2014), decision aids (Stacey 2017), personalised care planning (Coulter 2011), family‐centred care (Shields 2012), or family‐initiated care escalation interventions (Mackintosh 2020). These interventions promote person‐centred care by focusing on consumer involvement in the clinical consultation process, which influences the responsiveness of care delivery at the level of individual consumers. Interpersonal and communication skills training of providers also helps to promote person‐centred care in the consultation process (Dwamena 2012; Gilligan 2021; Repper 2007).

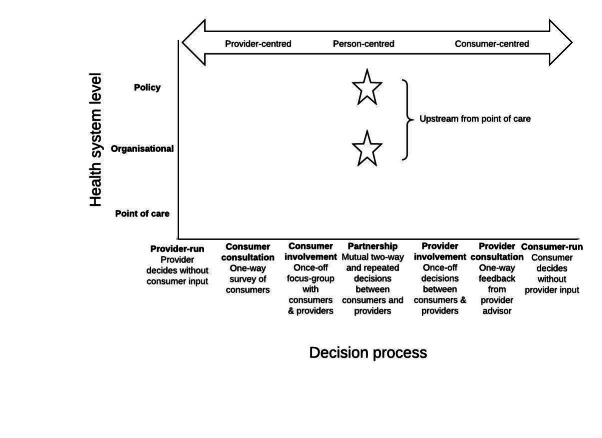

In contrast, the current review focuses on the involvement of consumers in partnership with health providers as one of the key ways in which person‐centred care can be promoted at the health service level i.e. upstream, at a higher level than the point of care (Figure 2).

2.

Decision‐making at different levels of the health system influences the person‐centeredness of health services

Description of the intervention

Defining working in partnership as an intervention

The Australian Commission for Safety and Quality in Health Care defines partnerships as "healthcare organisations, healthcare providers, and policy‐makers actively working with people who use the healthcare system, to ensure that health information and services meet people’s needs" (ACSQHC 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) further defines partnership "as a collaborative relationship between two or more parties, based on trust, equality, and mutual understanding, for the achievement of a specified goal. Partnerships involve risks as well as benefits, making shared accountability critical” (WHO 2009). The WHO definition identifies partnerships as a form of collaboration. While ‘collaborate’ features on the participation spectrum (Arnstein 1969), and partnerships are considered an emergent process (Wildridge 2004; Wolf 2017), working in partnership is a distinct type of collaboration that occurs over a sustained time span to allow for the ongoing process of developing constructive relationships (Ocloo 2021). Hence, one‐off consumer participation in collaborations, even when they are intended to promote person‐centred care at the health service level, do not fit within the parameters of this review (Armstrong 2018; Fucile 2017; McKenzie 2017).

We included trials that evaluate the effects of working in partnership (i.e. collaborative relationships between at least one consumer and health provider, meeting jointly and regularly in formal group formats, to equally contribute to and collaborate in real‐time), on decisions intended to promote person‐centred care in one or more areas of a health service or services. These formal group formats could include committees, councils, boards, or steering groups, which meet more than once (either for an ongoing or time‐limited duration) in real‐time (face‐to‐face or virtually).

Purpose(s) of working in partnership

Promoting person‐centred care at the health service level may be achieved by working in partnership to set priorities, identify problems, design solutions, or implement initiatives that reorient the responsiveness of health services towards the information and service delivery needs and experiences of consumers (Figure 3). Partnership approaches to develop policies or identify and monitor performance indicators may also influence person‐centred care at the health service level. Working in partnership on such decisions may improve health service performance ratings of affordability, physical accessibility, acceptability, safety, quality, service availability, and accountability. Working in partnership may improve the responsiveness of health services to the consumers who use them (ACSQHC 2011; Doyle 2013; Edgman‐Levitan 2013; National Patient Safety Foundation 2014; Rathert 2012). Working in partnership on these decisional activities may result in changes that promote person‐centred health services.

3.

How working in partnership may influence person‐centred care outcomes at the health service level

In research, numerous terms connote working in partnership at the health service level. Working in partnership underpins participatory action research, co‐production, user‐centred design, experience‐based design, and co‐design (Batalden 2016; Cooke 2016; Jun 2018; Sanders 2008). Common to these collaborative decision‐making approaches is that they empower consumers at the health service level (Sanders 2008) and may reorient health services from a ‘provider‐focus’ to a ‘patient‐focus’ (Luxford 2011). Partnership approaches to decision‐making are frequently illustrated by the maxim ‘nothing about me, without me’ (Berwick 2009; Coulter 2011; Delbanco 2001; Nelson 1998) and a move from the clinical paradigm of 'what is the matter?' to 'what matters to you?' (Edgman‐Levitan 2013).

Optimising partnership working

Ottmann and colleagues caution that engagement and participation of consumers alone does not suffice to enable this shift. They argue that to ensure truly collaborative decision‐making, the contribution of stakeholder voices requires monitoring and amplification where necessary, in order to account for intrinsic power imbalances (Ottmann 2011). For example, in their research, administrative and operational ‘imperatives' dominated consumers’ voices; to address this power imbalance, the researchers adopted the role of consumer advocate (Ottmann 2011). We planned to conduct a subgroup analysis that focused on the effects of attempts to address intrinsic power imbalances in preparation for partnerships, for example, by providing a salary or financial reimbursement, orientation, training, coaching, or support (via an advocate, facilitator, moderator, or mentor). However, there were insufficient trials to do so.

How consumers are selected can also contribute to power imbalances, for example, by handpicking or inviting ‘appropriate’ or ‘acquiescent’ representatives, or by overlooking class or ethnic groups from whom comments are seldom heard (Ocloo 2016). Another power imbalance to be considered is whether the partnership is professionally dominated (Ocloo 2016). Therefore, in subgroup analysis, we planned to consider the methods of recruitment, whether the researchers ensured the inclusion of a diverse consumer or provider participant group (e.g. caregivers, vulnerable people, range of health providers) and the ratio of consumers to providers (e.g. consumer majority, provider majority, or equal). Due to too few included trials, we were unable to conduct planned subgroup analyses.

How the intervention might work

Working in partnership interventions might work by strengthening the demand responsiveness and local accountability of health services, by including consumers in health service planning and policy decision‐making (Björkman Nyqvist 2017). Responsiveness and accountability require information about (1) the needs, preferences, experiences, and priorities of consumers of the service, as well as (2) ratings of health service(s), such as performance indicators. Consumers and health providers working in partnership, means that both consumer and provider perspectives are available, and feed into health service decision‐making (Edgman‐Levitan 2013).

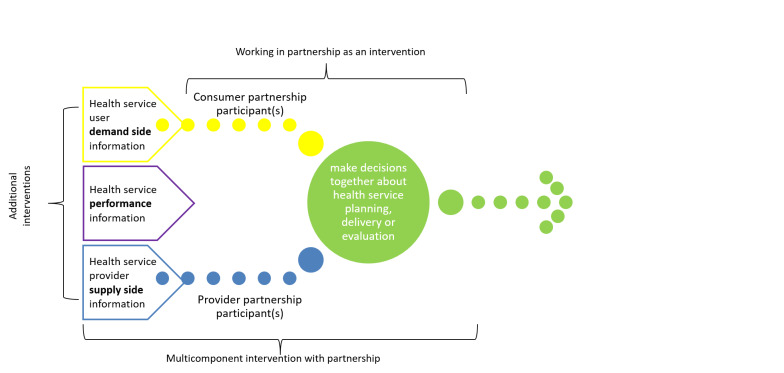

Recent trials focusing on working in partnership vary in the frame of reference for partnership decision‐making. In some trials, the consumers and health providers directly involved in the partnership (the partnership participants) approach decision‐making using their own experience as a point of reference (Björkman Nyqvist 2017; Ong 2017; Palmer 2015; Palmer 2016). In other trials, the partnership participants are explicitly required to incorporate additional information that has been gathered systematically, as part of the trial, into their decision‐making (Björkman 2009; Greco 2006; Gullo 2017; Waiswa 2016). This additional information may include the broader health service user perspectives (demand side), the broader provider perspectives (supply side), or health performance information (see Figure 4).

4.

‘Working in partnership' interventions alone and as a component of multi‐component interventions

We differentiated between working in partnership as an intervention on its own, which only incorporates the viewpoints of the consumer and provider partnership participants into their decision‐making; and working in partnership as part of a multi‐component intervention, in which partnership participants consider additional information (e.g. demand side, supply side, or performance information) that has been gathered systematically, as part of the trial, into their decision‐making.

Why it is important to do this review

The primary objective of this review is to identify whether a common type of partnering with consumers (meeting together in formal group formats) is effective in achieving person‐centred health services. This review parallels a Cochrane QES that explores consumers' and health providers' experiences of the same format (Merner 2019). We anticipate that combining the results of both reviews will provide guidance for consumers, health providers and policymakers about this form of partnership and together form a comprehensive and cohesive assessment of the evidence on partnering.

Trials evaluating the effects of upstream interventions of consumer involvement in developing health care policy, research, and services have been synthesised in other systematic reviews (Hubbard 2007; Nilsen 2006). Nilsen and colleagues focus on all forms of consumer engagement (i.e. consult, involve, collaborate and empower) (Nilsen 2006). We limit our focus to partnership approaches (i.e. collaborate but with an ongoing or time‐limited duration, excluding one‐off collaborations). We also limit our focus to decisional activities intended to promote person‐centred care in one or more areas of a health service(s), whereas Nilsen 2006 and Hubbard 2007 both focus on broader types of activities in all areas of research, policy, and healthcare services, with consumers broadly (Nilsen 2006), and people affected by cancer (Hubbard 2007). An overview of reviews of the theory, barriers and enablers for consumer and public involvement across health, social care and consumer safety has also recently been published (Ocloo 2021). However, no reviews have specifically evaluated the effects of consumers working in partnership, as an intervention to promote person‐centred health services, which is the focus here.

An earlier review in this area explored the effects of involving consumers in the planning and development of health care, but at that time, there were no comparative or experimental studies available (Crawford 2002). Crawford and colleagues identified that involving consumers contributed to changes to services. However, they also noted that the effects of involvement on quality of care (accessibility and acceptability of services) or impact on consumers' satisfaction, health, or quality of life, had not been examined (Crawford 2002). In the absence of trial evaluations, reviews based on research in this upstream context have focused on consumer participation and involvement predominantly as an agenda or aspiration, with guidance based on case studies of one‐off collaboration examples. Sharma and colleagues identified that engaging people in partnerships, shared decision‐making, and meaningful participation in health system improvement, all promoted person‐centred care (Sharma 2015).

Given recently conducted or planned trials in the area (Greco 2006; Palmer 2015; Palmer 2016), a systematic review is timely. The Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group has also identified the promotion and implementation of person‐centred care as a priority review topic (Synnot 2018; Synnot 2019).

By focusing on partnership activities, our review contributes to Cochrane's growing evidence base for interventions to promote person‐centred care, which currently has an exclusive focus on consumer participation in interventions occurring at the point of care (Coulter 2015; Dwamena 2012; Legaré 2014; Mackintosh 2020; Shields 2012; Stacey 2017).

Objectives

To assess the effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership, as an intervention to promote person‐centred health services.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs, and quasi‐RCTs (a trial in which randomisation is attempted, but subject to potential manipulation, such as allocating participants by day of the week, date of birth, or sequence of entry into the trial), as we anticipated that few, properly conducted RCTs will have focused on consumers and health providers working in partnership.

Types of participants

We included trials in which the following groups were participants.

Consumer partnership participants. Consumer partnership participants refers to people who are fulfilling an advisory or representative role within the partnership. These roles might include a consumer or patient representative; consumer consultant; consumer with acute or chronic condition(s), their caregiver or family member; community members, general public or citizens; representatives, consultants, or members of consumer organisations.

Health provider partnership participants. Health provider partnership participants refers to people who are fulfilling an advisory or representative role within the partnership. These roles might include, for example: a clinician (such as doctor, nurse, allied health, or community health worker from any discipline), health service manager, supervisor or administrator (including quality coordinators, chief executives, etc.), health policy‐maker, or consumer liaison officer. As we are interested in partnerships between consumers and health providers, we will exclude partnerships in which health providers take on the role of consumer, or partnerships between consumers and providers who are primarily health researchers or academics.

Health service users and health service providers. Health service users and health service providers refers to the consumers and providers who are not directly involved in the partnership intervention, but are participants in trials that evaluate the effects of the partnership intervention.

Partnership groups could include multiple stakeholders, as long as the goal was to make decisions to promote person‐centred care. Partnerships could be committees that developed in‐service training or vocational education curriculum directed towards post‐registration or post‐graduate level students, as long as they included at least one consumer.

Types of interventions

We included trials evaluating the effects of consumers and health providers working in partnership as an intervention, to make decisions with the aim of promoting person‐centred care in one or more areas of a health service or services. We included trials of working in partnership in formal groups that meet face‐to‐face or virtually, more than once.

We defined person‐centred care as “planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among healthcare providers, patients, and families” (IPFCC 2012). Examples of person‐centred care decisions at the health service level included: identify appropriate and responsive healthcare indicators; improve continuity or follow‐up of care; service (re)development, (re)design of physical spaces, or improve coordination of care across providers and settings (or a combination).

We included trials evaluating the effects of consumers and providers working in partnership in formal groups or committees to develop in‐service training or vocational education curriculum directed towards post‐registration or post‐graduate level students (i.e. student cohort likely to be existing providers, and therefore partnership intervention may influence person‐centredness of health service).

We defined health services as public or privately funded services that provide direct care to consumers in primary (e.g. community health centres, general practitioner practices, private practices, dispensaries), secondary (e.g. specialist outpatient clinics), or tertiary settings (e.g. hospitals). We included home and residential services only when they primarily provide health or nursing care (e.g. home‐based nursing services, nursing homes, residential rehabilitation services, or hospices).

Working in partnership has three key components (see Table 3): (1) both consumer and provider participants meet (2) jointly (e.g. face‐to‐face, online, phone) in a formal group format regularly (e.g. over time, more than once), to (3) to consider or make an actual decision that relates to the person‐centredness of health service(s).

1. Key components of working in partnership versus usual practice.

| Key components of working in partnership | (1) Partnership participant types | (2) Joint formal group format, meets over time | (3) Decision relates to person‐centeredness of health service | |||

| Working in partnership as an intervention | At least one consumer | At least one heath service provider | Opportunity to influence deliberation and decision‐making by meeting jointly (e.g. f2f, online, phone) |

Formal group format (e.g. board, committee, council, steering or work group) |

Meets more than once (e.g. time‐limited or ongoing) |

Joint decisions about health service planning, delivery, or evaluation |

| Usual practice – may contain some, but not all, key components of working in partnership | e.g. no consumer participant, or consumer(s) involved, but not in decision‐making | (or) no health service provider participant, or provider(s) involved, but not in decision‐making | (or) group does not meet jointly e.g. independent deliberation and decision‐making |

(or) group is informal or ad‐hoc | (or) group meets only once | (or) either the consumer or health service provider participant provides feedback, or acts in an advisory or consultative capacity, rather than decision‐making, for health service planning, delivery, or evaluation |

We assess three comparisons in this review. Comparisons 1 and 2 assess the effects of partnership versus no partnership (with no other differences between groups), while Comparison 3 compares the effects of different versions of partnership.

Comparison 1. Consumers and health providers working in partnership compared to usual practice without partnership (i.e. usual ways of decision‐making may contain some but not all key components of working in partnership).

Studies for this comparison answer the question: ‘compared to usual practice without partnership, what is the effectiveness of consumers and health providers working in partnership, as an intervention?’. For example, ‘what is the effect of facilitated partnership (intervention) compared to no partnership (usual practice)?’ illustrates this comparison (Palmer 2015).

Examples of usual practice may include:

decision‐making involves some consumer input, but decisions are not made jointly;

providers independently make decisions;

decision‐making meets some key components, but group format is informal, meets once‐off, or does not meet together in real‐time.

Comparison 2. Consumers and health providers working in partnership, as part of a multi‐component intervention, compared to the same multi‐component intervention without consumers and health providers working in partnership.

Studies for this comparison answer the question: ‘what is the effectiveness of a multi‐component intervention that includes consumers and health providers working in partnership, compared to the same multi‐component intervention without partnership?’. For example, ‘what is the effect of facilitated partnership plus health service consumer (demand side) information (multi‐component intervention with partnership) compared to health service consumer (demand side) information without partnership (same multi‐component intervention without partnership)?’ serves to illustrate this comparison (Greco 2006).

For example, a multi‐component intervention may include co‐interventions, such as health service consumer or provider information (demand and supply), or health service performance information (or both). Working in partnership would be part of one multi‐component intervention arm, but not the other.

Comparison 3. One form of consumers and health providers working in partnership, compared to another form of consumers and health providers working in partnership.

Studies for this comparison answer the question: ‘what is the effectiveness of one form, versus another, of consumers and health providers working in partnership, as an intervention?’. For example, both groups have working in partnership interventions that fulfil all key components, but the intervention and comparator groups differ in the nature of a key feature, such as partnership participant composition (ratio of consumers and providers), or frequency, or format (online format versus face‐to‐face) of the meetings.

Excluded interventions

We excluded trials where the comparison did not enable us to isolate the effects of consumers and providers working in partnership. This included:

consumers and health providers working in partnership as part of a multi‐component intervention compared to usual practice; or

consumers and health providers working in partnership, compared to an active control that does not include working in partnership (i.e. comparator is a different intervention).

In these cases, the comparisons will not allow us to evaluate the effect of working in partnership as an intervention, as the intervention and comparator groups differ on more than just the partnership component. An example illustrative of an excluded comparison is, ‘what is the effect of health service consumer (demand side) information plus partnership (multi‐component intervention with partnership) compared to no health service consumer (demand side) information and no partnership (usual practice)?’ (Boivin 2014).

As working in partnership is a distinct type of collaboration that occurs over time, we excluded one‐off collaborations involving consumers in group formats, even when they are intended to promote person‐centred care. We excluded studies that involve partnering with consumers for decision‐making about an individual's care or treatment. We also excluded studies about partnering with consumers for health services research (planning, undertaking, or disseminating research), including a health service’s management of research (research funding panels, setting research priorities, research ethics and research governance (Gray‐Burrows 2018)).

We excluded trials that examine committees that develop educational programmes or training for pre‐registration or undergraduate students, as we are interested in working in partnership as a strategy to promote person‐centred health services. Undergraduate students may not yet be employed as providers, and therefore less able to either directly or indirectly influence the person‐centredness of the health service as part of the intervention (Klein 1999).

As we are interested in consumer‐provider partnerships, we excluded studies of researchers or academics working in partnership with consumers if providers were not also partnership participants. Similarly, we excluded studies in which researchers or academics were working in partnership with health providers, if consumers were not partnership participants.

Types of outcome measures

This is the first Cochrane Review on this topic and so included a wide range of outcomes to inform future conceptual development and research. We did not identify from trials any additional outcomes that we did not anticipate at the protocol stage and that we considered important to consumers or health providers making decisions.

Health service alterations (changes to services resulting from decisions)

Addition, rationalisation, substitution, expansion, or revision of health services (e.g. changes to policies, performance indicators, resources, processes or systems, programmes, settings (e.g. relocating a stroke rehabilitation service from the hospital to the community), education, information, physical structures, or culture or values of services)

Degree to which health service alterations reflect health service user (trial participant) priorities (demand responsiveness)

Comparability of partnership decision(s) with health service user preference(s) or priorities

Health service user (trial participant) health service performance ratings (local accountability)

Physical accessibility, e.g. simplified appointment procedures, extended opening times, transport to unit, parking, signage, security

Affordability

Acceptability e.g. satisfaction, retention or disengagement of existing consumers, attracting new consumers, appointment attendance or nonattendance

Safety

Quality

Accountability

Health service user (trial participant) ratings of health service utilisation patterns

Uptake of altered services or changes in coverage

Health service provider (trial participant) outcomes

Satisfaction, staff engagement, retention or turnover, well‐being

Adverse events

Measures of complaints, harms, litigation, damage to health service reputation, staff disengagement or turnover, increased rate of consumer failure to attend appointments, etc.

Resource use

Cost (time, money) associated with decision‐making process (e.g. cost of organising and running meetings, training (providers and consumers), remuneration, coordination, or meeting space)

Cost (time, money) associated with implementing new or changes in service

Consumer (partnership participant) outcomes*

Attendance and retention rates in formal group formats

Preparedness to participate (e.g. feeling informed, motivation or empowerment to be involved, attitudes towards partnership, etc.)

Experiences of participation (e.g. satisfaction, preferences, knowledge, well‐being, involvement, etc.)

Adverse outcomes and experiences (e.g. isolation, exploitation, uncertainty, conflict, decreased well‐being, disengagement from health service)

Provider (partnership participant) outcomes*

Attendance and retention rates in formal group formats

Preparedness to participate (e.g. feeling informed, confidence, attitudes towards partnership, etc.)

Experiences of participation (e.g. satisfaction, preferences, job satisfaction, well‐being, etc.)

Adverse outcomes and experiences (e.g. dissatisfaction, worsening attitudes towards consumers, emotional exhaustion, work overload, decreased well‐being, disengagement or resigning from employment, and conflict)

Measures of partnership among provider and consumer partnership participants*

Degree of shared decision‐making involvement, capacity building, trust, etc

We expected that outcomes denoted above with a star (*) would likely be measured for both the intervention and control groups only in Comparison 3 (e.g. in head‐to‐head comparison of partnership interventions).

We did not exclude studies based on the presence or absence of outcomes reported.

Two review authors independently assigned the outcomes reported in each included study to the review’s outcome categories, and resolved any differences in categorisation by involving a third review author.

Where more than one outcome measure was available in one trial for the same outcome we planned to:

select the primary outcome that has been identified by the study authors;

where no primary outcome was identified, we planned to select the one specified in the sample size calculation;

if there were no sample size calculations, we planned to rank the effect estimates (i.e. listed them in order from largest to smallest) and select the median effect estimate;

where there were an even number of outcomes, we planned to select the outcome whose effect estimate is ranked n/2, where n is the number of outcomes.

We planned to use the selection steps above to inform the statistical analysis (i.e. pooling, synthesis). However, as there were insufficient trials for statistical analysis, we collected data on more than one outcome measure per category per trial to inform descriptive findings. Where a study reported multiple outcome measures for the same outcome, we extracted all. Review authors then met to discuss and reach consensus on the most relevant outcome measure for evaluating partnering with consumers (whether objective or subjective). This outcome was selected to take forward for the analysis of intervention effectiveness.

Timing of outcome assessment

We grouped time points into short‐, medium‐, and long‐term time points. For the purpose of meta‐analysis, we planned to select one time point for each outcome from each study. However, as we did not have sufficient numbers of trials measuring the outcomes to be able to conduct meta‐analyses, we chose to report descriptively the longest‐term time point because this was most likely to be relevant to consumers and decision makers.

Main outcomes for ‘Summary of findings’ tables

We reported the following outcomes in the ‘Summary of findings’ tables.

Health service alterations (changes to services resulting from decisions).

Degree to which changed service reflects health service user priorities (demand responsiveness).

Health service user (trial participant) ratings of health service performance (local accountability).

Health service user (trial participant) health service utilisation patterns.

Resources associated with decision‐making process.

Resources associated with implementing decisions (e.g. changed services).

Adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases (searches were initially conducted in April 2019 and then updated on 23 February 2021):

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, to 8 April 2019);

MEDLINE Ovid* (1946 to 8 April 2019);

Embase Ovid* (1947 to 8 April 2019);

PsycINFO Ovid* (1806 to April Week 1 2019);

CINAHL EBSCO Host* (1937 to 8 April 2019);

PROQUEST Dissertations and Theses Global* (2016 to 8 April 2019).

Studies identified as potentially relevant from the updated searches run in February 2021 are listed as Studies awaiting classification, to be considered in future updates to the review.

The outputs of databases denoted above with a star (*) were sorted by the Cochrane RCT Classifier. The RCT Classifier assigned a probability (from 0 to 100) to each citation for being a true randomised trial. The titles and abstracts of any records determined by RCT Classifier to be unlikely to be an RCT (or quasi‐RCT) with the classifier scores of nine or less were screened by one review author for potential inclusion. Two authors independently screened the citations classified as likely to be an RCT. All records determined to be relevant in terms of scope at title and abstract screening stage were then screened in full text by two review authors.

We searched online trial registers including ClinicalTrials.gov at the US National Institutes of Health (from 2000 to 23 February 2021), and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (from 2000 to September 2019). For the updated search in February 2021, it was assumed that both registries were covered by updated searches of other databases, as registry records have been made available via CENTRAL since April 2019).

We present the strategy for MEDLINE Ovid in Appendix 2. We tailored this strategy to other databases and report them in Appendix 3, Appendix 4, Appendix 5, Appendix 6, Appendix 7 and Appendix 8.

We also searched Web of Science (2000 to 8 April 2019) using the ‘All databases’ option to search forward on citations of 14 selected references, used to validate the search strategy; see Appendix 9.

We restricted the search period, as the qualitative review scoping searches of this topic showed a proliferation of studies about partnering with consumers published after 2000. Additionally, the definition of person‐centred care has developed considerably over the past decades to include aspects broader than partnering with individuals during consultations. Our assessment shows that a consistent and recognisable definition of working in partnership to promote person‐centred health services has been used most often since 2000. We aimed to assess and build the evidence on what is currently accepted as partnering in the context of person‐centred health services. Therefore, in this review, we searched from 2000 onwards to exclude older, conceptually inconsistent studies. We excluded publications in languages other than English.

Searching other resources

We searched relevant grey literature sources, such as websites (e.g. the WHO, Health Quality Improvement Partnership UK, Involve UK, Health Foundation UK, Beryl Institute, James Lind Alliance, International Association for Public Participation, Institute for Patient‐ and Family‐Centered Care (formerly Picker Institute Europe), Health Issues Centre Australia, Planetree, The King's Fund, Consumer Health Organisation of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the patient group ‐ One Voice Patient & Family Advisory Council, Mayo Clinic USA) during September 2019.

We attempted to contact experts in the field and authors of included studies to identify other potentially relevant studies. We searched reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

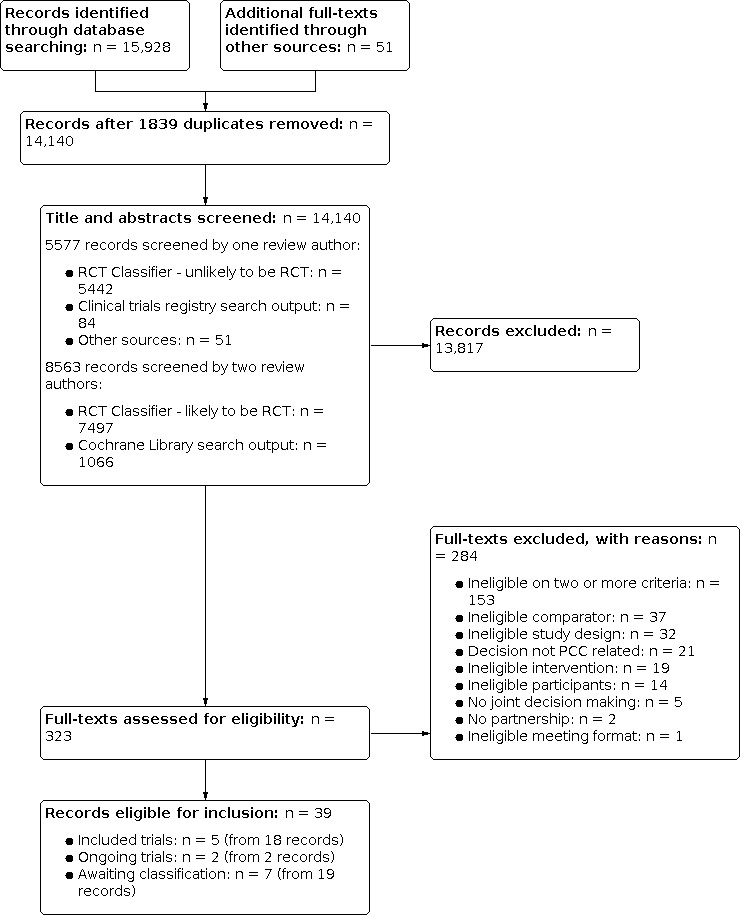

To determine titles and abstracts that met the inclusion criteria, a subset of citations identified by searches were screened by one review author (records classified as unlikely to be RCTs by the RCT Classifier or identified through search of the clinical trials registries or other sources) and the remainder (records classified as likely to be RCTs by the RCT Classifier and those identified through the Cochrane Library search) were independently screened by at least two review authors, with consensus decisions made by a third review author. All the references identified at title and abstract stage and considered relevant by one or more review author were retrieved in full text. Two review authors independently screened all full‐text articles for inclusion or exclusion, with discrepancies resolved by discussion, and by consulting a third review author, if necessary, to reach consensus. We list all potentially relevant papers excluded from the review at this stage, with reasons provided in the ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’. We also provide citation details and any available information about ongoing studies, and collate and report details of duplicate publications, so that each study (rather than each report) is the unit of interest in the review. We report the screening and selection process in an adapted PRISMA flow chart in Figure 5 (Liberati 2009).

5.

PRISMA diagram

Data extraction and management

One review author extracted data for all included studies and a second review author independently cross‐checked all data. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. We developed and piloted a data extraction form, using Cochrane Consumers and Communication's data extraction template. We extracted data on the following items: details of the study; risk of bias items; criteria related to precision of the study (e.g. use of a power calculation); funding source and the declaration of interests for the primary investigators; details of consumers and providers; and setting. One review author entered all extracted data into Review Manager 5; a second review author independently checked entered data for accuracy against the data extraction sheets (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and report on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and the Cochrane Consumers and Communication guidelines, which recommend the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting (Higgins 2011; Ryan 2013).

For cluster‐RCTs, we also assessed and report the risk of bias associated with an additional domain, selective recruitment of cluster participants.

We planned to assess and report quasi‐RCTs as being at a high risk of bias for random sequence generation.

We considered blinding separately for different outcomes (for example, blinding may have the potential to differently affect subjective versus objective outcome measures). We judged each item as being at high, low, or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria provided by Higgins 2011, and provide a quote from the study report and a justification for our judgement for each item in the 'Risk of bias' table.

We deemed studies to be at the highest risk of bias if we scored them as at high or unclear risk of bias for either the sequence generation or allocation concealment domains, based on growing empirical evidence that these factors are particularly important potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011).

One review author assessed risk of bias for all included studies and a second review author independently cross‐checked all assessments, consensus was reached by resolving any disagreements through discussion. We attempted to contact study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods. We incorporated the results of the ‘Risk of bias' assessment into the review through standard tables, descriptive synthesis, and commentary about each of the elements. We provide an overall assessment of the risk of bias of included studies and a judgment about the internal validity of the review’s results.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to analyse data based on the number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups. We planned to use these to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous measures, we planned to analyse data based on the mean, standard deviation (SD), and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups to calculate mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. If the MD was reported without individual group data, we used this to report the study results. If more than one study measured the same outcome using different tools, we planned to calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI using the inverse variance method in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

For any included cluster‐RCTs, we checked for unit‐of‐analysis errors. Where we found errors, and sufficient information was available, we planned to re‐analyse the data using the appropriate unit of analysis, by taking account of the intracluster correlation (ICC). We planned to obtain estimates of the ICC by contacting authors of included studies, or imputing them using estimates from external sources. It was not possible to obtain sufficient information to re‐analyse the data, so we reported effect estimates and annotated any unit‐of‐analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

For participant data, where possible, we conducted analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis; otherwise, data were analysed as reported. We reported on the levels of loss to follow‐up and reasons, and assessed this as a source of potential bias.

For missing outcome or summary data, we planned to impute missing data, and report any assumptions in the review. We planned to investigate, through sensitivity analyses, the effects of any imputed data on pooled effect estimates; however, there were too few studies to do so.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to examine the heterogeneity across studies, to determine if there were considerable differences in settings, interventions, participants, and outcomes, and used this descriptive analysis to determine the most appropriate groupings of studies within each of the review's main comparisons. Where studies were considered similar enough (based on consideration of these factors) to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we planned to assess the degree of heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots, and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was to be quantified using the I² statistic. An I² value of 50% or more was to be considered to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, and this value was to be interpreted in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value from the Chi² test (Higgins 2011). As there were insufficient studies pool effect estimates, we did not explore possible reasons for variability by conducting subgroup analysis.

Included studies were too dissimilar due to substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity to pool statistically, therefore we did not report pooled results from meta‐analysis, but instead used a descriptive approach to data synthesis. There were too few studies to group studies with similar populations, intervention and methodological features to explore differences in intervention effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias qualitatively, based on the characteristics of the included studies (e.g. to determine if only small studies that indicate positive findings are identified for inclusion).

We did not identify sufficient (i.e. 10 or more) studies for inclusion in the review, and therefore we did not construct a funnel plot to investigate small study effects, which may indicate the presence of publication bias. Therefore, we did not formally test for funnel plot asymmetry (Higgins 2011). Instead, publication bias was assessed by determining whether the included studies were likely to be representative of all relevant studies that have been conducted and where there were completed trials not yet published we considered this suggestive of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We could not conduct meta‐analyses as planned due to an insufficient number of studies identified within each comparison and each outcome. We decided not to meta‐analyse data as the included trials were not similar enough in terms of participants, settings, intervention, comparison, and outcome measures to ensure meaningful conclusions from a statistically pooled result.

As we were unable to pool the data statistically using meta‐analysis we conducted a descriptive synthesis of results. We present the major outcomes and results, organised by intervention categories according to the major types or aims (or both) of the identified interventions. Due to lack of trials, it was not possible to explore the possibility of organising the data by population, and explore heterogeneity in the results by investigating the subgroups identified below. Within the data categories, we explore the main comparisons of the review:

partnership intervention versus usual practice (without partnership);

multi‐component intervention with partnership versus multi‐component intervention without partnership;

one form of partnership intervention versus another.

If we had identified studies assessing the effects of more than one intervention, we would have compared each separately with usual practice, and with one another.

Using the synthesised quantitative findings to supplement the Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis (QES)

The QES informed development of this review (Merner 2019). While we planned at the outset of these two pieces of work to integrate qualitative and quantitative findings from this review in the discussion (Harden 2018), the sparse data available and small number of trials included in this review did not lend itself to an in‐depth interpretation through a qualitative lens. Future updates of this review may consider looking at contextual and other information offered by the accompanying QES, but only if it is meaningful to do so.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A statistical subgroup analysis was not possible, nor was it possible to examine explanatory factors to explore the effects of interventions descriptively.

Sensitivity analysis

There were too few included studies to undertake planned sensitivity analyses.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in health care

Both the protocol for this review and the related QES protocol were co‐designed with a stakeholder advisory panel who were also to be directly involved in the production of the QES at the review stage (Merner 2019). A draft of the protocol for this review was shared with the stakeholder advisory panel prior to a stakeholder workshop day. During the workshop, the stakeholders provided the following feedback on the protocol.

Refine definitions to reflect practice e.g. consumers and health providers often ‘make decisions together’ rather than ‘sharing responsibility for decisions’.

Define terms in understandable, or lay language.

A diagram or infographic showing the differences between the effectiveness review and the QES is needed to help with clarity.

Explain the differences between point of care versus partnership in health service.

Clarify if Consumer Liaison Officer has a complaints role or advocate role.

Consider (in subgroup analyses) the role of power differentials, consumer representatives, whether led or chaired by consumers or professionals, who initiated the group, who leads partnerships, and hierarchies within service (e.g. palliative care – multidisciplinary care).

Relevant outcomes might include: participatory outcomes, such as cohesion or collaboration (perhaps in measures of increasing involvement or capacity building); consumer participation as stepping stone to higher‐level participation and involvement (i.e. capacity building, which benefits the individual consumer and the system); and personal well‐being. Decisions might result in: changes in systems or services; improved accessibility (of parking, signage, security and reduced theft); more dissemination of changed services and outcomes; rationalised services (i.e. increased focus on those that consumers want, on those that add value); growth in services (i.e. may demonstrate increased need); change of setting (e.g. hospital service to community, hospital to home setting); staff engagement, retention, etc; and financial cost savings (i.e. if experienced staff stay on, this may be more cost‐effective than adding new staff). Adverse events might include stakeholder disengagement, negative impacts on reputation, noncompliance, and failure to attend at point of care.

Relevant grey literature search sites might include: Beryl Institute, Health Foundation UK; work in Canada with First Nations (i.e. indigenous) people have led the way with community‐led engagement.

The stakeholder panel feedback resulted in the following changes to the protocol.

Changed ‘sharing responsibility for decisions’ to ‘make decisions together’ or alternatively ‘jointly make decisions’.

Glossary added to define terms (see Appendix 1).

Modified the infographic of the funnel diagram to outline the different steps in the qualitative and quantitative systematic review approaches (see Figure 1).

Developed figure to highlight the level of the health system where partnership‐based decision‐making might impact the person‐centeredness of health services (i.e. national, state, regional (policy) level, or local health service governance (organisational) level, as opposed to the direct care (point of care) level (see Figure 2)).

Removed the term 'Consumer Liaison Officer' as an example in the background, and referred instead to a consumer advocate role as a support component of facilitated partnerships.

Added to the methods our intent to consider the identified potential sub‐group analyses, if number of included trials allows.

Added the identified outcomes.

Added the grey literature resources.

A content expert provided feedback on the protocol and review, as part of Cochrane Consumers and Communication’s standard editorial process.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence, using the GRADE criteria described in Schünemann 2011: methodological limitations, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias. We planned to prepare a ‘Summary of findings’ table for each of the three comparisons outlined above. However, we did not prepare a table for Comparison 3, as none of the included studies examined one form of partnership intervention versus another. We did not use GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT) to present the results of the meta‐analysis, as the findings were limited to descriptive synthesis. The seven key outcomes outlined in the Types of outcome measures section are presented in 'Summary of findings' tables for Comparison 1: Partnership intervention versus usual practice and Comparison 2: Multi‐component intervention with partnership versus multi‐component intervention without partnership.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of ongoing studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The combined database searches yielded 15,928 records. We obtained an additional 51 full‐text records through other sources. After removing duplicates (n = 1839), we screened 14,140 titles and abstracts. Of the title and abstracts screened, 8563 records were screened by two review authors (i.e. records classified as likely to be RCTs by RCT Classifier, n = 7497; and records obtained through Cochrane Library search, n = 1066). One review author screened 5577 other records (i.e. those classified as unlikely to be RCTs by the RCT Classifier, n = 5442; those identified by search of clinical trials registries, n = 84; and those identified through other sources, n = 51). Two review authors independently screened 323 full‐text articles. We excluded 284 full‐text records that did not meet the inclusion criteria and recorded our reasons for exclusion (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

We included five studies (reported in 18 records). One is an RCT (Jha 2015), and four are cluster‐RCTs (Greco 2006; O'Connor 2019; Persson 2013; Wu 2019). Two studies (Kjellström 2019; Sawtell 2018) are ongoing (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). Studies identified as potentially relevant from the updated searches run in February 2021 are listed as Studies awaiting classification. Seven studies (English 2018; Gai 2019; James 2013: Lindquist 2020; Morrison 2020; Palmer 2015; Shrestha 2011) reported in 19 records are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). See Figure 5 for PRISMA diagram.

Included studies

Participants

A total of 16,257 health service users and at least 469 health service providers were trial participants in the five included studies (the number of included provider trial participants was unknown in Wu 2019). In two studies, the trial participants were health service users only (mothers with live births (Persson 2013) and pregnant women or mothers of children aged under five (O'Connor 2019)); in one study, the trial participants were health service providers only (first‐year medical trainee doctors employed in hospitals; Jha 2015); and in two studies, both health service users and providers were trial participants (Greco 2006; Wu 2019).

In two studies, all health service users were female (O'Connor 2019; Persson 2013), reflecting the trials' focus on maternal and child health; and in the other two studies the majority (63% to 68%) of health service users were female (Greco 2006; Wu 2019). None of the three studies including health service providers as trial participants provided demographic details (Greco 2006; Jha 2015; Wu 2019), although in Jha 2015 all participants were doctors in their first year after medical school and so were all considered to be at the same level. See Table 4 for more details of participants.

2. Study demographics.

| Study | Country; Degree of regional development; Healthcare setting | Partnership participants | Trial participants | Demographic details |

|

Jha 2015 RCT 283 first year trainee doctors randomised to partnership and usual practice |

Country: England Regional development: High‐income country; predominantly urban sites Healthcare setting: Post graduate medical schools at 5 hospital sites (unclear if public/privately funded) |

Consumer partners: 6 patients and 5 carers who had experienced harm or error during healthcare either to themselves or their families Provider partners: 8 clinicians involved in medical education of foundation year trainees |

Health service users: none Health service providers: 283 first year medical trainee doctors employed by 5 hospitals sites |

Consumer partners: None available (N/A) Provider partners: N/A Health service users: none; not relevant (N/R) Health service providers: N/A |

|

Persson 2013 Cluster‐RCT 90 communes* (a geopolitical unit) were randomised to partnership and usual practice *with 6306 births and neonatal mortality rate of 24/1000 live births in 2005. Communes with a lower mortality rate were excluded from the trial. |

Country: Vietnam Regional development: Middle‐income country; village sites Healthcare setting: Communities served by Commune Health Centres with 3‐6 staff members providing primary health care including reproductive and antenatal care to approximately 1000‐18,000 people. Delivery care is offered by Commune Health Centres, or by hospitals at district, province and regional levels. Each Commune Health Centre has a Village Health Worker who provides basic healthcare in the villages. |

Consumer partners: 11 members of the Women's Union recruited as lay women facilitators of Maternal and Newborn Health Groups (MNHG) Provider partners: Commune Health Centre staff (physician, midwife, nurse); a commune Village Health Worker, a population collaborator, the chairperson/vice chairperson of the commune; and two Women's Union representatives. Each of the 44 MNHGs had 8 members (352 partnership participants). |