Abstract

Uterine spiral arteries are extensively remodeled during placentation to ensure sufficient delivery of maternal blood to the developing fetus. Uterine spiral arterial remodeling is complex, as cells originating from both mother and developing conceptus interact at the maternal interface to regulate the extracellular matrix remodeling and vasculature restructuring necessary for successful placentation. Despite this complexity, one mechanism critical to spiral artery remodeling is trophoblast cell invasion into the maternal compartment. Invasive trophoblast cells include both interstitial and endovascular populations that exhibit spatiotemporal differences in uterine invasion, including proximity to uterine spiral arteries. Interstitial trophoblast cells invade the uterine parenchyma where they are interspersed among stromal cells. Endovascular trophoblast cells infiltrate uterine spiral arteries, replace endothelial cells, adopt a pseudo-endothelial cell phenotype, and engineer vessel remodeling. Impaired trophoblast cell invasion and, consequently, insufficient uterine spiral arterial remodeling can lead to the development of pregnancy disorders, such as preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and premature birth. This review provides insights into invasive trophoblast cells and their function during normal placentation as well as in settings of disease.

Keywords: hemochorial placentation, invasive trophoblast cells, extravillous, intrauterine invasion, hypoxia

Introduction

Uterine spiral arterial remodeling at the maternal/placental interface is a multifaceted process involving numerous cell types. In addition to invasive trophoblast cells, maternal immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, contribute to uterine spiral artery remodeling [1–3] and are critically important for successful placentation. However, the key signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating cell-mediated uterine spiral artery remodeling accompanying hemochorial placentation are largely unknown. Several in vitro and in vivo model systems have been developed and utilized to study aspects of trophoblast cell invasion and trophoblast cell-immune cell-vascular interactions. Advantages and limitations of each experimental system are evident and important to consider when developing a research plan or when interpreting results from published studies. In the following paragraphs, we discuss selected examples of regulatory processes implicated in the control of trophoblast cell guided-uterine spiral artery remodeling and highlight the value of integrating in vitro and in vivo models for studying invasive trophoblast cell lineage development and trophoblast cell invasion in hemochorial placentation research. When available we will defer to in vivo experimentation in our physiological assessment of hemochorial placentation. In vitro experimentation can be a powerful means of understanding molecular and biochemical mechanisms regulating cell differentiation and in generating hypotheses; however, it is necessary to appreciate that analyses of cells in culture are artificial and reflect the potential of a cell in a prescribed condition, which may or may not reflect a physiologic state. Human placental tissue specimens are also a valuable resource and provide opportunities for histological, biochemical, and molecular analyses, the establishment of correlations with normal and disease states, and integration with in vitro and in vivo investigations.

Invasive trophoblast cells and uterine spiral artery remodeling

The placenta engineers the redirection of maternal blood flow to provide the fetus with necessary nutrients and oxygen for successful development. As fetal development progresses, maternal uterine spiral arteries are remodeled to accommodate increased nutrient and oxygen demands and to attenuate the negative consequences of shear stress, which can lead to placental injury [4]. Impaired uterine spiral artery remodeling leads to suboptimal fetal conditions and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Adverse pregnancy outcomes include pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm birth [5]. Fetal adaptive responses to suboptimal conditions during intrauterine life affect postnatal health and susceptibility to adult disease [6].

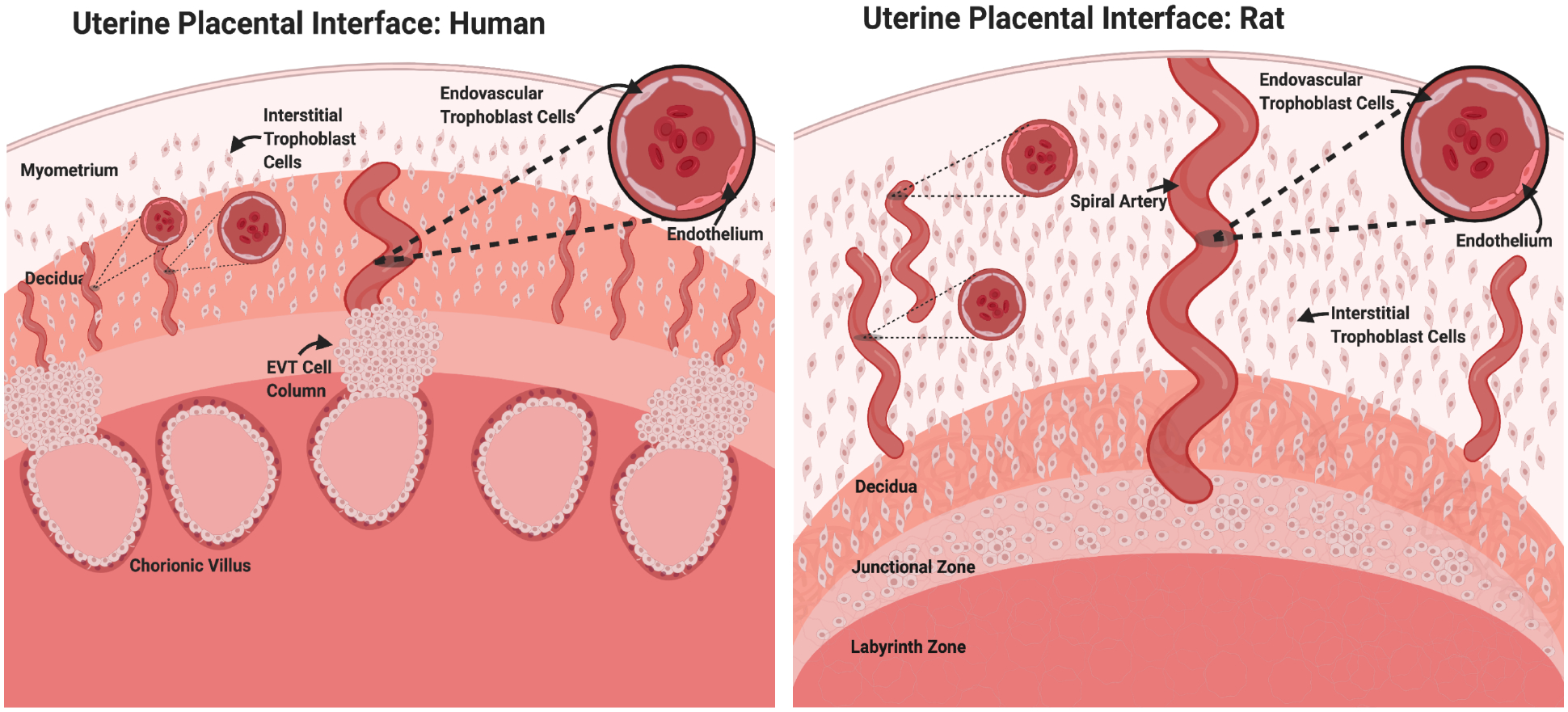

Uterine spiral artery remodeling is complex, as diverse cell populations participate in and regulate the multi-step remodeling process, which includes trophoblast cell infiltration of maternal tissue, vascular cell loss, and extracellular matrix remodeling [7]. Two main populations of invasive trophoblast cells contribute to restructuring the uterine parenchymal compartment: i) interstitial trophoblast cells; ii) endovascular trophoblast cells (Figure 1, Table 1). In the human, invasive trophoblast cells are referred to as extravillous trophoblast cells. The generic term ‘invasive trophoblast cell’ is used to refer to trophoblast cells entering and transforming the uterine parenchyma from species that do not possess a villous placenta, including rodents. Species conservation exists in the development and actions of invasive trophoblast cells [8]. However, some notable differences have been identified. Species differences are evident in the route of invasion (endovascular versus interstitial), the presence of trophoblast cell plugs within the uterine vasculature, the repair of endothelial cells following vessel remodeling, and, especially, in the depth of intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion [8,9]. The mouse is a widely used experimental model but, unfortunately, many features of intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion in the mouse are unique (e.g., shallow intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion) and are not observed in human placentation [10,11]. In contrast, the rat exhibits several features of intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion shared with human placentation, including deep intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion [8,12]. The rat is an experimentally tractable animal model ideal for investigating trophoblast-uterine parenchymal cell interactions [12–14]. Invasive trophoblast cell populations arise from analogous placental structures in the human and rat, the extravillous trophoblast column and the junctional zone, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trophoblast cell invasion in the human and the rat.

Similar to the human, the rat possesses a hemochorial placenta with deep trophoblast invasion and extensive spiral artery remodeling. Trophoblast cells invade both interstitially and endovascularly through uterine spiral arteries where they replace endothelial cells and adopt a pseudo-endothelial cell phenotype. In the human, invasive extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells are derived from cell progenitors residing in extravillous cell columns. The analogous site of trophoblast progenitors in the rat is the junctional zone.

Table 1.

Selected features of invasive trophoblast cells

| Cell Type | Endovascular invasive trophoblast cells | Interstitial invasive trophoblast cells |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Features |

|

|

| Human: KRTs, HLA-G, ASCL2, FASLG, MMP12, MMP2, MMP9, CCR1, CDH5, CD31, CD56 | Human: KRTs, HLA-G, ASCL2 | |

| Rat: KRTs, PRL2A1, PRL5A1, PRL7B1, ASCL2, MMP12, CD31 | Rat: KRTs, PRL2A1, PRL5A1, PRL7B1, ASCL2 |

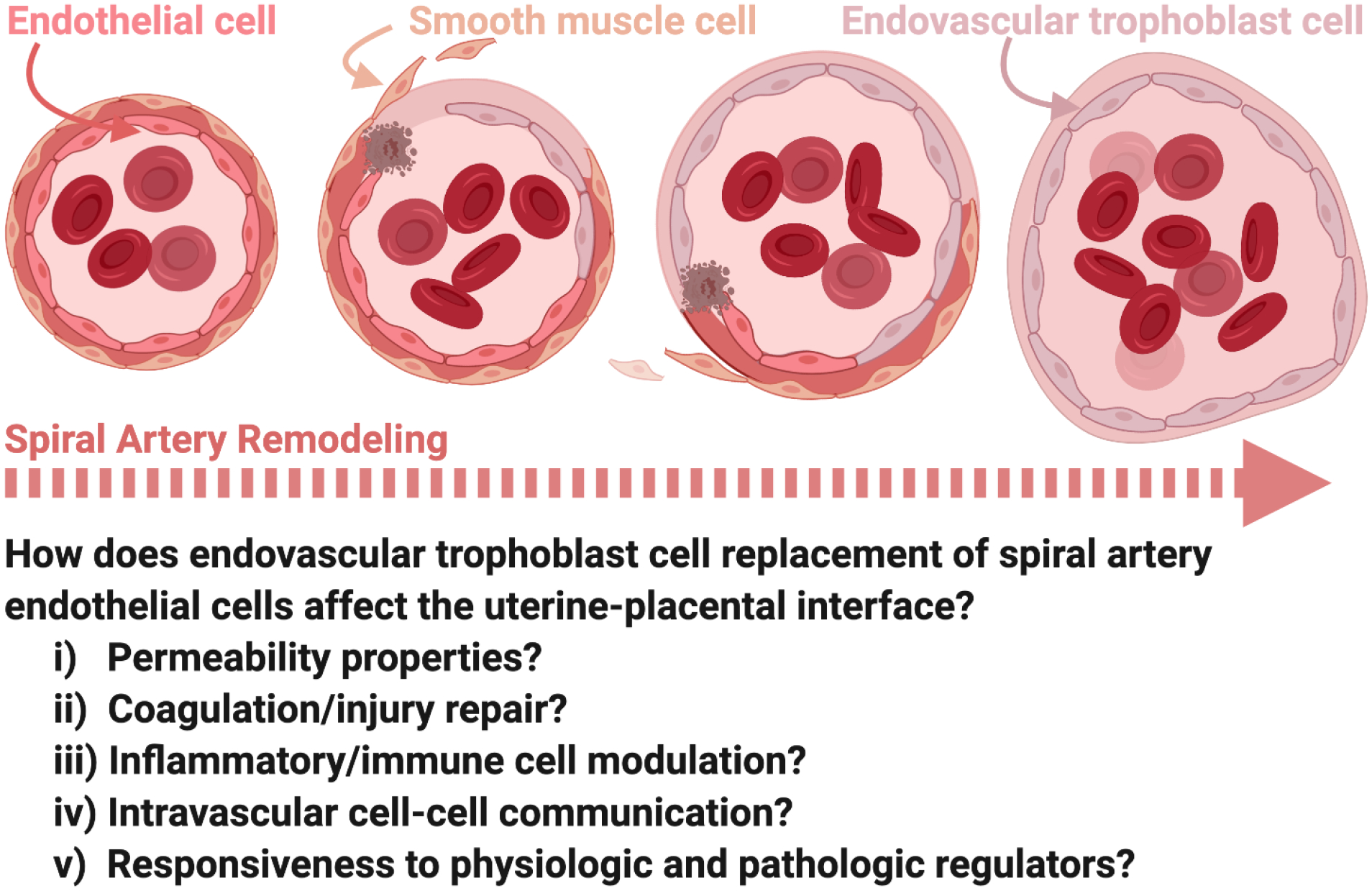

Interstitial and endovascular trophoblast cells can display deep intrauterine invasion during gestation and can be distinguished by spatiotemporal differences in their migratory patterns. Interstitial trophoblast cells invade the endometrial parenchyma and remain spread throughout the stroma following invasion (Figure 1). Conversely, endovascular trophoblast cells infiltrate uterine spiral arteries and localize to vessel lumens where they replace endothelial cells and adopt a pseudo-endothelial cell phenotype (Figures 1, 2) [15,16]. Despite positional differences, very few cell-specific markers of invasive endovascular and interstitial trophoblast cells have been identified [17]. CD56 has previously been identified as a discriminatory antigen expressed on the surface of endovascular plug cytotrophoblasts, but not in interstitial invasive trophoblast cells (Table 1) [17]. Limited knowledge of discrete cell markers has made it difficult to discriminate between these trophoblast cell populations at the molecular level.

Figure 2. Endovascular trophoblast cell-regulated uterine spiral artery remodeling.

Endovascular trophoblast cells migrate through spiral arteries where they actively promote remodeling. As spiral artery remodeling progresses, vascular smooth muscle cells surrounding the arteries are removed and basement membrane is modified. Remodeling also involves removal of the endothelium and replacement by endovascular trophoblast cells which adopt a pseudo-endothelial phenotype. Many questions remain as to the significance of endovascular trophoblast cells replacing endothelial cells lining remodeled spiral arteries.

Recent advances in single cell RNA-sequencing have enabled identification of discrete cell populations, including trophoblast cells, at the maternal/placental interface [18–21]. This advanced transcriptomic profiling approach, combined with visualization of transcript expression patterns, provides new insights into invasive interstitial and endovascular trophoblast cell populations as well as potentially other less appreciated invasive trophoblast cell sub-populations [22,23].

Invasive trophoblast cells have also been localized to uterine veins, lymphatic vessels, and endometrial glands [22,23]. These routes of trophoblast invasion are likely connected to trophoblast-mediated uterine parenchymal restructuring to facilitate maternal support for placental and fetal development. For example, trophoblast-directed endometrial gland modifications may ensure delivery of endometrial gland histiotrophic secretions required for extraembryonic and embryonic development [24]. Further investigation into the function of invasive trophoblast cells present within these distinct uterine structures will inform how they safeguard pregnancy success or, when inadequate or absent, contribute to a range of pathological states.

Origin of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage

As mentioned earlier, invasive trophoblast cells arise from the extravillous trophoblast column and the junctional zone of the human and rat, respectively. In the extravillous trophoblast column a continuum can be observed from stem/progenitor cells located at the base of the column (proximal) to differentiating extravillous trophoblast cells situated at the distal end of the column [25–27]. NOTCH1 signaling drives expansion of extravillous trophoblast progenitor cells [28]. Cells advancing to the distal part of the extravillous trophoblast column are destined for intrauterine invasion. As extravillous trophoblast cells enter the uterine parenchyma additional differentiation processes can transpire, including endoreduplication and cell fusion [29,30], as well as specialization into endovascular trophoblast cells [15]. WNT signaling may contribute to end-stage extravillous trophoblast cell development [31]. Cells distributed between the proximal stem/progenitor cells and distal extravillous trophoblast cells represent intermediate stages of extravillous trophoblast cell differentiation.

The junctional zone has been recognized for its contributions to the endocrinology of the rodent placenta [32,33]. Trophoblast stem/progenitor cell populations and multiple differentiated cell types are identified in the junctional zone [34,35]. Indeed, spongiotrophoblast cells and trophoblast giant cells represent two of the differentiated cell fates involved in the production of steroid and peptide hormones [32,34]. These cell types may be subdivided into an assortment of subtypes [34,36]. Cells accumulating glycogen, termed glycogen trophoblast cells, are a transitory cell population of the junctional zone. Glycogen trophoblast cells are viewed as contributors to the endocrine and metabolic activities of the rodent placenta and are possibly linked to the invasive trophoblast cell lineage [37]. Both interstitial and endovascular invasive trophoblast cells arise from the junctional zone [13]. The AP-1 transcription factor complex consisting of FOS-related antigen 1 (FOSL1) and JUNB proto-oncogene (JUNB) drives early intrauterine endovascular trophoblast cell invasion [38,39].

Unlike the extravillous trophoblast column, the junctional zone does not exhibit a simple continuum of cellular development from proximal stem/progenitor cells to distal invasive trophoblast cells. Physical locations of stem/progenitor cells and differentiated cell types within the junctional zone appear to exhibit more complexity than observed in the extravillous trophoblast column. The increased complexity may arise from the multiple cell fates associated with the junctional zone versus the apparent singular mission of the extravillous trophoblast column [34,35].

There is conservation in the regulation of the extravillous trophoblast column and the junctional zone and their production of invasive trophoblast cells. For example, achaete scute homolog 2 (ASCL2) is expressed in the extravillous trophoblast column, the junctional zone, and in invasive trophoblast cells [40]. Disruption of ASCL2 interferes with junctional zone and invasive trophoblast cell development in the rat and in the progression of human stem/progenitor cell differentiation to extravillous trophoblast cells [40]. Most importantly, such insights highlight the conservation of this important regulatory process and the merits of investigating invasive trophoblast cell development in animal models.

Endovascular trophoblast cell acquisition of a pseudo-endothelial cell phenotype

Endovascular trophoblast cells migrate along and replace resident endothelial cells lining uterine spiral arteries. A FAS ligand (FASLG)-FAS cell surface death receptor (FAS) signaling pathway has been implicated in the regulation of endovascular trophoblast cell removal of uterine spiral artery endothelium [41]. Endovascular trophoblast cells produce FASLG, which engages FAS on the endothelial cell surface to induce apoptosis. This same pathway also contributes to endovascular trophoblast cell-directed vascular smooth muscle cell removal and uterine immune cell death [41–43].

As endovascular trophoblast cells supplant resident endothelial cells, they acquire an endothelial cell-like phenotype (Figure 2) [15,16]. This trophoblast cell to endothelial cell-like transformation is characterized by the expression of known endothelial cell-associated proteins, including endothelial cell adhesion molecules, matrix metalloproteinases, and a thromboregulatory gene expression program [15,16,44,45]. However, molecular mechanisms underlying acquisition of the pseudo-endothelial cell phenotype are yet to be determined. Replacement of spiral artery endothelium by endovascular trophoblast cells is a curious process. Vascular mimicry may enable endovascular trophoblast cells to thrive as resident cells along the vessel wall, but what purpose are they serving? What is the significance of having endovascular trophoblast cells line the vessel wall instead of the prototypic endothelial cell lining of the vasculature? Could there be advantages due to inherent differences between endovascular trophoblast cells and endothelial cells in one or several of the following functional properties, e.g., cell and/or molecular permeability, thrombotic processes, injury repair, inflammatory responses, immune cell modulation, and/or intravascular cell-cell communication? Additionally, an important feature of blood vessels lined by endovascular trophoblast cells versus endothelial cells may be associated with critical differences in each cell type’s responsiveness to physiologic and pathologic regulators. Comparing endovascular trophoblast cell and endothelial cell biology is further complicated by the extensive heterogeneity of endothelial cells [46]. Nonetheless, seeking answers to the above queries has considerable merit and will advance our understanding of a fundamental process contributing to healthy placentation. In the final analysis, positive pregnancy outcomes are supported by endovascular trophoblast cell replacement of uterine spiral artery endothelium.

Rheological properties impact uterine spiral artery remodeling

Rheological properties impact uterine spiral artery remodeling and subsequent placental pathologies [4]. Fluid shear stress, resulting from blood flowing through vessels, is dependent on several different variables including flow rate, blood viscosity, as well as vessel length and diameter. During uterine spiral artery remodeling, vessel diameter and fluid flow rates change, such that endovascular trophoblast cells are likely exposed to a broad range of shear stress levels. In humans, trophoblast cells plug uterine spiral arteries until 10–12 weeks of gestation [47]. Trophoblast cell plugs impede blood flow through the artery, which is proposed to create a low oxygen environment facilitating trophoblast cell expansion and invasion to ensue. Detailed analyses have indicated that trophoblast cell plugging of uterine spiral arteries is dynamic and an important factor affecting hemodynamics of downstream blood delivery to the placenta, and upstream blood flow in the spiral arteries [48]. Experimentation from James and co-workers supports the concept that trophoblast cells migrate in the direction of blood flow [49]. Relationships between shear stress and the activation of trophoblast cell invasion are critical to understanding trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery remodeling.

Hypoxia-mediated signaling pathways promote endovascular trophoblast cell invasion

Hemochorial placentation is responsive to oxygen tension. Low oxygen tensions can elicit critical adaptive responses, such that failed adaptation can lead to development of placental pathologies [50,51]. Insights have been gained from analyses of human pregnancies exposed to chronic hypoxia at high altitude and from a range of experimental manipulations restricting oxygen delivery to the placentation site [51,52].

Oxygen tension is a remarkably effective experimental tool to investigate placentation site-specific adaptations in the rat. About a decade ago, we determined that hypoxia exposure alters placental structure and stimulates intrauterine endovascular trophoblast cell invasion; two adaptations critical to the success of pregnancy. Specifically, decreasing oxygen concentration to ~11% (hypoxic) relative to an ambient environment (21% oxygen at sea level) from gestation days 6.5 to 13.5 resulted in expansion of the junctional zone (source of invasive trophoblast cell progenitors) and deep penetration of trophoblast cells into uterine spiral arteries [53]. The critical developmental window for hypoxia-stimulated trophoblast cell invasion is between gestation days 8.5 and 9.5. Importantly, trophoblast cell invasion following hypoxia exposure is restricted to the endovascular trophoblast cell population, as changes in interstitial trophoblast cell invasion are not observed at gestation day 13.5 [53]. Recent studies have focused on identifying the molecular mechanisms responsible for hypoxia-induced endovascular trophoblast cell migration from the junctional zone into the uterine parenchymal compartment.

Studies from our laboratory identified hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) signaling as a key pathway in the activation of the hypoxia-dependent invasive trophoblast cell lineage [3]. HIF transcriptionally increases lysine demethylase 3A (KDM3A) expression. KDM3A is a histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) demethylase mediating HIF-dependent gene regulation. Hypoxia stabilizes HIF leading to increased KDM3A and an epigenetic landscape favoring the expression of genes characteristic of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage. Among these downstream targets is matrix metallopeptidase 12 (MMP12), an elastase critical to trophoblast cell migration and invasion and uterine spiral artery remodeling in both rat and human placentation sites [3,45,54–56]. Importantly, in addition to the observations made in rat models of hemochorial placentation, conditions of decreased oxygen delivery are also associated with development of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage and uterine spiral artery remodeling in the monkey and human [57,58]. Low oxygen dependent EVT cell development can be replicated in vitro with primary human trophoblast cells [3,56,59]. Experimental evidence also supports a role for HIF-KDM3A-MMP12 dysregulation in the etiology of placental pathologies, including preeclampsia [3]. MMP12 is not the only matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) that has been implicated in placentation and pregnancy complications [60,61]. Several studies have identified MMP2 and MMP9 as two other prominent MMPs involved in regulating trophoblast cell invasion (Table 1) [62,63].

A role for oxygen tension as a driver of endovascular trophoblast cell invasion and vascular remodeling should not be a surprise. Low oxygen represents an effective stimulus for activation of cellular events promoting angiogenesis and vasculature restructuring, which commonly occur in embryogenesis and following cell transformation [64,65].

Uterine NK cell contributions to trophoblast cell invasion and uterine spiral artery remodeling

NK cells are critically involved in transformation of the uterine parenchyma during the establishment of pregnancy [66–69]. The impact of maternal uterine NK cells on trophoblast cell invasion is somewhat controversial [70]. Evidence supports the idea that invasive trophoblast cells possess intrinsic abilities to invade in the absence of signals from the uterus [71]. Paradoxically, experimental observations indicate that the uterus is a source of signals that can promote or restrain trophoblast cell invasion [1,67,72,73]. Since NK cells comprise the majority of leukocytes within the uterus during placentation, our laboratory sought to identify how in vivo deficits in NK cells affect uterine spiral artery remodeling and trophoblast cell invasion [2,74]. Two strategies were used to create rat models with deficits in NK cells: i) immunodepletion; ii) genome-edited disruption of the Il15 gene, which encodes the main trophic factor for NK cell development. Both approaches yielded NK-cell deficiencies resulting in substantial structural changes within the placenta including increased junctional zone size, accelerated deep endovascular trophoblast cell invasion, and extensive endovascular trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery remodeling [2,74]. A similar role for NK cells in limiting trophoblast cell invasion has also been observed in mouse placentation [75,76]. This in vivo experimentation supports the hypothesis that uterine NK cells restrain early trophoblast cell invasion, thereby delaying uterine spiral artery remodeling. As gestation progresses, invasive trophoblast cells are capable of overwhelming NK cell mediated restraint, leading to invasive trophoblast cell infiltration into the uterine parenchyma and the exit of NK cells [75].

Similar NK cell-invasive trophoblast cell relationships exist in human placentation. NK cells are prominent features of the placentation site during the early stages of pregnancy and diminish as gestation advances [77–80]. Placentation site disease states also provide insights about NK cell-invasive trophoblast cell dynamics. NK cell deficiencies, as seen in ectopic-tubal pregnancies and in placenta accreta, are associated with expanded trophoblast cell invasion [81–85]. Connections between NK cells and invasive trophoblast cells in disorders of impaired intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion (e.g., preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction) are more complicated and could be impacted by NK cells numbers and/or NK cell phenotype. It is also important to acknowledge that the relationship between NK cells and invasive trophoblast cells may be more complicated. In vitro experimentation has demonstrated NK cells can produce factors promoting trophoblast cell migration and invasion [86,87]. Whether these in vitro results reflect a true physiological role of NK cells in modulating invasive trophoblast cells remains to be determined.

The relationship between NK cells and invasive trophoblast cells extends beyond NK cells regulating trophoblast cell invasion. NK cells also importantly contribute to uterine spiral artery remodeling prior to the entry of invasive trophoblast cells [69,74,88,89] and persist in the absence of robust intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion [90]. Thus, although based on in vivo observations, NK cells and invasive trophoblast cells possess what appears to be a mutual antagonism, they cooperate to ensure effective uterine spiral artery remodeling.

Chemokines and adhesion molecules regulate endovascular trophoblast cell invasion

The impact of chemokines and adhesion molecules on trophoblast cell migration and invasion have been assessed. Several in vitro studies have evaluated trophoblast cell-endothelial cell interactions, including chemokine secretion both in the presence of shear stress and in static culture conditions [91,92]. Following shear stress exposure, human uterine microvascular endothelial cells co-cultured with trophoblast cells exhibit altered expression and distribution of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1) [91]. Additionally, treatment with trophoblast cell-conditioned medium increased microvascular endothelial cell ICAM1 expression, promoted endothelial cell secretion of C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5, also called RANTES), increased trophoblast cell adhesion to endothelial cells, and enhanced endothelial cell permeability [91]. CCL5, along with interleukin-8 (IL8) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2, also called MCP-1) have previously been shown to promote trophoblast cell migration [49]. Chemokines originating in the endometrium also direct endovascular trophoblast cell invasive properties. CC chemokine receptor 1 (CCR1) is preferentially expressed in human endovascular trophoblast cells and its ligands are expressed in cells residing in the uterine stroma [93–95]. Activation of CCR1 signaling promotes human trophoblast cell invasiveness. Conversely, the soluble form of melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM, also called CD146), is thought to impair invasive trophoblast cell functions including migration, outgrowth, and network formation [96]. Collectively, these results suggest that both trophoblast cells and endothelial cells secrete different factors that regulate one another. Thus, endothelial cell-trophoblast cell interactions exhibit a complex and temporally sensitive pattern of regulation.

Choudhury and co-workers investigated an intricate signaling system involving invasive trophoblast cells, endothelial cells, and leukocytes [92]. Specifically, extravillous trophoblast cells secrete interleukin-6 (IL6) and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8) to prompt endothelial cells to secrete C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 6 (CXCL6) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14) [92]. Endothelial-secreted CXCL6 and CCL14 ligands are proposed to regulate uterine NK cell and macrophage functions, since both leukocyte cell types express receptors for these ligands. These findings suggest a complex regulatory signaling network involving extravillous trophoblast cells, endothelium, and leukocytes during early stages of uterine spiral artery remodeling.

Model systems for studying invasive trophoblast cell lineage development

Studying the complexities of the multi-step uterine spiral arterial remodeling process has proven difficult due to tissue availability and ethical limitations that impede the study of human placentation [97]. Therefore, cell culture and animal models have been developed to enable in vitro and in vivo interrogation of molecular mechanisms underlying this pivotal event in hemochorial placentation and associated pathologies. In the next sections, we highlight promising model systems for elucidating regulatory mechanisms controlling the invasive trophoblast cell lineage.

In vitro model systems

Considerable effort has been exerted to establish the optimal cell population for investigating the invasive trophoblast lineage. Limitations in the in vitro analysis of human invasive trophoblast cells is evident [98]. Invasive trophoblast cells are most active in early phases of human pregnancy, which are difficult to obtain, and immortalized/transformed human trophoblast cell lines are inherently compromised as models for investigating properties of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage [98]. Trophoblast stem cells and organoids have emerged over the past few years as effective tools for dissecting mechanisms underlying the development of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage.

Trophoblast stem cells.

Trophoblast stem cells, which were first isolated and characterized twenty years ago in the mouse [99] and subsequently in the rat [100], represent effective in vitro model systems for analysis of trophoblast cell differentiation. Rodent trophoblast stem cells have been effectively used to investigate regulation of invasive trophoblast cells [3]. Until very recently, human trophoblast stem cell isolation and culture have proven elusive. Okae, Arima, and colleagues established a cell culture systems for in vitro propagation of human trophoblast stem cells and their differentiation into extravillous trophoblast cells [101]. WNT and epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling are critical for maintenance of the stem state and their removal essential for trophoblast cell differentiation. The human trophoblast stem cell culture system is robust and has positively advanced our understanding of molecular mechanisms controlling human trophoblast cell lineage development [40,102–106].

Building on the knowledge gained from the human trophoblast stem cell model, recent efforts have focused on the derivation of human trophoblast stem cell lines from pluripotent stem cells [107–109]. The advent of this new source of human trophoblast stem cells is critical because the establishment of human trophoblast stem cells from blastocysts and first trimester tissue sources is restricted for many investigators. Pluripotent stem cells provide other benefits, including a broader genetic diversity than available in the original human trophoblast stem cell lines and a greater potential for genetic manipulation to understand critical molecular mechanisms and pathways driving invasive trophoblast cell lineage development.

Trophoblast organoids.

Advancements have been made to recapitulate aspects of trophoblast cell development in three-dimensions (3D) with trophoblast organoid models [110,111]. Trophoblast organoids consist of purified, first-trimester (6–9 weeks of gestation) cytotrophoblasts mixed with Matrigel® containing several growth factors and small molecule inhibitors to promote self-renewal [111]. Activation of WNT and EGF signaling and inhibition of transforming growth factor/bone morphogenetic protein signaling have been used to establish trophoblast organoid cultures [110,111]. Organoids can be expanded, maintained in culture for several months, and cryopreserved for recultivation. Trophoblast organoids are informative models for several reasons including the use of primary cytotrophoblast, defined culture conditions, long-term culture potential, 3D organization, and the ability to induce differentiation into both syncytiotrophoblast and HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblast cells. Although access to first trimester primary cytotrophoblast cells is a significant challenge to using this model, incorporating a 3D component to an in vitro model has advanced our ability to model trophoblast cell biology in the dish.

Co-culture systems.

Trophoblast cells can be seeded on top of artery segments embedded in fibrin gels to mimic interstitial invasion, or perfused into lumen arteries to simulate endovascular invasion [112,113]. Fluorescently labeling trophoblast cells prior to co-culture allows for discernment of discrete cell populations in this in vitro model system and enables the direct examination of cell interactions during invasion. The source of trophoblast cells in these co-culture systems has not always been optimal. Use of human trophoblast stem cells or trophoblast organoids in these more complex culture systems is a logical extension of the approach and will provide new insights. Co-culture systems can be meritorious; however, they generate complexities and obstacles for molecular and biochemical analyses.

Overview.

Trophoblast stem cells and trophoblast organoids represent significant advances in understanding the derivation of the extravillous/invasive trophoblast cell lineage. In vitro model systems can facilitate elucidation of cell potential but fall short as tools to understand the physiology and pathophysiology of trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery remodeling. Implementation of physiologically relevant in vivo models to test hypotheses controlling development and function of the invasive trophoblast cell lineage and trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery remodeling is essential to advance the field.

In vivo model systems

Hemochorial placentation is utilized by many mammalian species. Importantly, the hemochorial placenta comes in different forms, which impacts the suitability of animal models for investigating trophoblast cell invasion and uterine spiral artery remodeling. In contrast to the mouse, the rat exhibits hemochorial placentation with deep intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion, a feature also observed in human placentation [8,12]. Global and trophoblast cell lineage-specific gene manipulations (loss-of function and gain-of-function) can be effectively performed in the rat and represent powerful tools for tracking the invasive trophoblast cell lineage and investigating molecular mechanisms controlling the invasive trophoblast cell lineage and uterine spiral artery remodeling [3,39,40,114]. In its optimal form, this will require identifying candidate regulators of invasive trophoblast cells. Interrogation of the uterine-placental interface using single cell RNA sequencing should provide a means for identifying candidate regulators controlling invasive trophoblast cell development. It is important to appreciate that not all regulatory events controlling invasive trophoblast cell development and trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery will be shared in the rat and human. Identification of similarities and differences will be informative and will advance our understanding of this critical process in hemochorial placentation.

Other species, such as the guinea pig, hamster, and some nonhuman primates, exhibit deep trophoblast cell invasion [8]; however, at this juncture experimentation with these alternative models is not practical. Moving beyond phenomenology is not a trivial exercise. Advancements in the use of alternative models will require the establishment of methodologies for in vitro trophoblast cell propagation, differentiation, and manipulation, as well as strategies for in vivo placentation assessment and genetic manipulation for each species.

Final Thoughts

In summary, insufficient trophoblast cell invasion resulting in impaired spiral artery remodeling is associated with the development of severe pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction [115]. Importantly, these pregnancy complications impact not only maternal health, but also fetal and postnatal health. Despite the fact that preeclampsia is the leading cause of all pregnancy-related morbidities and impacts 5–8% of all pregnancies, effective preventative and therapeutic interventions have yet to be identified. Further investigation into mechanisms of trophoblast cell-guided uterine spiral artery remodeling is necessary to enable earlier detection of disease onset and to develop safe and effective interventions.

Highlights.

Uterine spiral arteries are restructured to ensure blood delivery to the fetus

Insufficient uterine spiral arterial remodeling can lead to pregnancy disorders

Maternal immune cells and trophoblast cells interact to regulate spiral artery remodeling

Invasive trophoblast cell lineage development is critical to uterine transformation

Acknowledgements

We recognize current and past lab members of the Soares laboratory for contributing to our research effort. The figures in this manuscript were created with BioRender.com. This work was supported by a Lalor Foundation postdoctoral fellowship and an NRSA postdoctoral fellowship to KV from the National Institutes of Health (F32HD096809), grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD020676; HD079363, HD099638) and the Sosland Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose and no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- [1].Chakraborty D, Rumi MAK, Soares MJ, NK cells, hypoxia and trophoblast cell differentiation, Cell Cycle. 11 (2012) 2427–2430. 10.4161/cc.20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Renaud SJ, Scott RL, Chakraborty D, Rumi MAK, Soares MJ, Natural killer-cell deficiency alters placental development in rats, Biol. Reprod 96 (2017) 145–158. 10.1095/biolreprod.116.142752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chakraborty D, Cui W, Rosario GX, Scott RL, Dhakal P, Renaud SJ, Tachibana M, Rumi MAK, Mason CW, Krieg AJ, Soares MJ, HIF-KDM3A-MMP12 regulatory circuit ensures trophoblast plasticity and placental adaptations to hypoxia, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113 (2016) E7212–E7221. 10.1073/pnas.1612626113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JCP, Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy, Placenta. 30 (2009) 473–482. 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brosens I, Puttemans P, Benagiano G, Placental Bed Research: 1. The placental bed. From spiral arteries remodeling to the great obstetrical syndromes, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol (2019) S000293781930746X. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burton GJ, Fowden AL, Thornburg KL, Placental origins of chronic disease, Physiol. Rev 96 (2016) 1509–1565. 10.1152/physrev.00029.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Harris LK, Review: Trophoblast-vascular cell interactions in early pregnancy: how to remodel a vessel, Placenta. 31Suppl (2010) S93–98. 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Animal models of deep trophoblast invasion, Placent. Bed Disord. Basic Sci. Its Transl. Obstet (2010). 10.1017/CBO9780511750847.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Silva JF, Serakides R, Intrauterine trophoblast migration: A comparative view of humans and rodents, Cell Adhes. Migr 10 (2016) 88–110. 10.1080/19336918.2015.1120397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC, Interactions between trophoblast cells and the maternal and fetal circulation in the mouse placenta, Dev. Biol 250 (2002) 358–373. 10.1006/dbio.2002.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hemberger M, Nozaki T, Masutani M, Cross JC, Differential expression of angiogenic and vasodilatory factors by invasive trophoblast giant cells depending on depth of invasion, Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat 227 (2003) 185–191. 10.1002/dvdy.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Soares MJ, Chakraborty D, Karim Rumi MA, Konno T, Renaud SJ, Rat placentation: an experimental model for investigating the hemochorial maternal-fetal interface, Placenta. 33 (2012) 233–243. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Soares MJ, Varberg KM, Iqbal K, Hemochorial placentation: development, function, and adaptations, Biol. Reprod 99 (2018) 196–211. 10.1093/biolre/ioy049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pijnenborg R, Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon G, Review article: trophoblast invasion and the establishment of haemochorial placentation in man and laboratory animals, Placenta. 2 (1981) 71–91. 10.1016/s0143-4004(81)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Damsky CH, Fisher SJ, Trophoblast pseudo-vasculogenesis: faking it with endothelial adhesion receptors, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 10 (1998) 660–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rai A, Cross JC, Development of the hemochorial maternal vascular spaces in the placenta through endothelial and vasculogenic mimicry, Dev. Biol 387 (2014) 131–141. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kam EP, Gardner L, Loke YW, King A, The role of trophoblast in the physiological change in decidual spiral arteries, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 14 (1999) 2131–2138. 10.1093/humrep/14.8.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vento-Tormo R, Efremova M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, Park J-E, Stephenson E, Polański K, Goncalves A, Gardner L, Holmqvist S, Henriksson J, Zou A, Sharkey AM, Millar B, Innes B, Wood L, Wilbrey-Clark A, Payne RP, Ivarsson MA, Lisgo S, Filby A, Rowitch DH, Bulmer JN, Wright GJ, Stubbington MJT, Haniffa M, Moffett A, Teichmann SA, Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal–fetal interface in humans, Nature. 563 (2018) 347–353. 10.1038/s41586-018-0698-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu Y, Fan X, Wang R, Lu X, Dang Y-L, Wang H, Lin H-Y, Zhu C, Ge H, Cross JC, Wang H, Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the diversity of trophoblast subtypes and patterns of differentiation in the human placenta, Cell Res. 28 (2018) 819–832. 10.1038/s41422-018-0066-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pique-Regi R, Romero R, Tarca AL, Sendler ED, Xu Y, Garcia-Flores V, Leng Y, Luca F, Hassan SS, Gomez-Lopez N, Single cell transcriptional signatures of the human placenta in term and preterm parturition, ELife. 8 (2019). 10.7554/eLife.52004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Suryawanshi H, Morozov P, Straus A, Sahasrabudhe N, Max KEA, Garzia A, Kustagi M, Tuschl T, Williams Z, A single-cell survey of the human first-trimester placenta and decidua, Sci. Adv 4 (2018) eaau4788. 10.1126/sciadv.aau4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moser G, Windsperger K, Pollheimer J, de Sousa Lopes SC, Huppertz B, Human trophoblast invasion: new and unexpected routes and functions, Histochem. Cell Biol 150 (2018) 361–370. 10.1007/s00418-018-1699-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huppertz B, Traditional and New Routes of Trophoblast invasion and their implications for pregnancy diseases, Int. J. Mol. Sci 21 (2019). 10.3390/ijms21010289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Burton GJ, Cindrova-Davies T, Turco MY, Review: Histotrophic nutrition and the placental-endometrial dialogue during human early pregnancy, Placenta. 102 (2020) 21–26. 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pollheimer J, Knöfler M, Signaling pathways regulating the invasive differentiation of human trophoblasts: a review, Placenta. 26Suppl A (2005) S21–30. 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harris LK, Jones CJP, Aplin JD, Adhesion molecules in human trophoblast - a review. II. extravillous trophoblast, Placenta. 30 (2009) 299–304. 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].James JL, Whitley GS, Cartwright JE, Pre-eclampsia: fitting together the placental, immune and cardiovascular pieces, J. Pathol 221 (2010) 363–378. 10.1002/path.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Haider S, Meinhardt G, Saleh L, Fiala C, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M, Notch1 controls development of the extravillous trophoblast lineage in the human placenta, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113 (2016) E7710–E7719. 10.1073/pnas.1612335113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Weier JF, Weier H-UG, Jung CJ, Gormley M, Zhou Y, Chu LW, Genbacev O, Wright AA, Fisher SJ, Human cytotrophoblasts acquire aneuploidies as they differentiate to an invasive phenotype, Dev. Biol 279 (2005) 420–432. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Velicky P, Meinhardt G, Plessl K, Vondra S, Weiss T, Haslinger P, Lendl T, Aumayr K, Mairhofer M, Zhu X, Schütz B, Hannibal RL, Lindau R, Weil B, Ernerudh J, Neesen J, Egger G, Mikula M, Röhrl C, Urban AE, Baker J, Knöfler M, Pollheimer J, Genome amplification and cellular senescence are hallmarks of human placenta development, PLoS Genet. 14 (2018) e1007698. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Knöfler M, Pollheimer J, Human placental trophoblast invasion and differentiation: a particular focus on Wnt signaling, Front. Genet 4 (2013) 190. 10.3389/fgene.2013.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Soares MJ, Chapman BM, Rasmussen CA, Dai G, Kamei T, Orwig KE, Differentiation of trophoblast endocrine cells, Placenta. 17 (1996) 277–289. 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].John RM, Epigenetic regulation of placental endocrine lineages and complications of pregnancy, Biochem. Soc. Trans 41 (2013) 701–709. 10.1042/BST20130002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Simmons DG, Cross JC, Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta, Dev. Biol 284 (2005) 12–24. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Marsh B, Blelloch R, Single nuclei RNA-seq of mouse placental labyrinth development, ELife. 9 (2020). 10.7554/eLife.60266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Simmons DG, Fortier AL, Cross JC, Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta, Dev. Biol 304 (2007) 567–578. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tunster SJ, Watson ED, Fowden AL, Burton GJ, Placental glycogen stores and fetal growth: insights from genetic mouse models, Reprod. Camb. Engl 159 (2020) R213–R235. 10.1530/REP-20-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kent LN, Rumi MAK, Kubota K, Lee D-S, Soares MJ, FOSL1 is integral to establishing the maternal-fetal interface, Mol. Cell. Biol 31 (2011) 4801–4813. 10.1128/MCB.05780-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kubota K, Kent LN, Rumi MAK, Roby KF, Soares MJ, Dynamic regulation of AP-1 transcriptional complexes directs trophoblast differentiation, Mol. Cell. Biol 35 (2015) 3163–3177. 10.1128/MCB.00118-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Varberg KM, Iqbal K, Muto M, Simon ME, Scott RL, Kozai K, Choudhury RH, Aplin JD, Biswell R, Gibson M, Okae H, Arima T, Vivian JL, Grundberg E, Soares MJ, ASCL2 reciprocally controls key trophoblast lineage decisions during hemochorial placenta development, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118 (2021). 10.1073/pnas.2016517118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ashton SV, Whitley GSJ, Dash PR, Wareing M, Crocker IP, Baker PN, Cartwright JE, Uterine spiral artery remodeling involves endothelial apoptosis induced by extravillous trophoblasts through Fas/FasL interactions, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 25 (2005) 102–108. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000148547.70187.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Abrahams VM, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Guller S, Mor G, First trimester trophoblast cells secrete Fas ligand which induces immune cell apoptosis, Mol. Hum. Reprod 10 (2004) 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kauma SW, Huff TF, Hayes N, Nilkaeo A, Placental Fas ligand expression is a mechanism for maternal immune tolerance to the fetus, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 84 (1999) 2188–2194. 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sood R, Kalloway S, Mast AE, Hillard CJ, Weiler H, Fetomaternal cross talk in the placental vascular bed: control of coagulation by trophoblast cells, Blood. 107 (2006) 3173–3180. 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Harris LK, Keogh RJ, Wareing M, Baker PN, Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Aplin JD, BeWo cells stimulate smooth muscle cell apoptosis and elastin breakdown in a model of spiral artery transformation, Hum. Reprod 22 (2007) 2834–2841. 10.1093/humrep/dem303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Dumas SJ, García-Caballero M, Carmeliet P, Metabolic signatures of distinct endothelial phenotypes, Trends Endocrinol. Metab. TEM 31 (2020) 580–595. 10.1016/j.tem.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].James JL, Saghian R, Perwick R, Clark AR, Trophoblast plugs: impact on uteroplacental haemodynamics and spiral artery remodelling, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 33 (2018) 1430–1441. 10.1093/humrep/dey225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Roberts VHJ, Morgan TK, Bednarek P, Morita M, Burton GJ, Lo JO, Frias AE, Early first trimester uteroplacental flow and the progressive disintegration of spiral artery plugs: new insights from contrast-enhanced ultrasound and tissue histopathology, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 32 (2017) 2382–2393. 10.1093/humrep/dex301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].James JL, Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Greenhill DR, Hoppe A, The regulation of trophoblast migration across endothelial cells by low shear stress: consequences for vascular remodeling in pregnancy, Cardiovasc. Res 93 (2012) 152–161. 10.1093/cvr/cvr276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Burton GJ, Oxygen, the Janus gas; its effects on human placental development and function, J. Anat 215 (2009) 27–35. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Soares MJ, Iqbal K, Kozai K, Hypoxia and placental development, Birth Defects Res. 109 (2017) 1309–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zamudio S, The placenta at high altitude, High Alt. Med. Biol 4 (2003) 171–191. 10.1089/152702903322022785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rosario GX, Konno T, Soares MJ, Maternal hypoxia activates endovascular trophoblast cell invasion, Dev. Biol 314 (2008) 362–375. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Desforges M, Harris LK, Aplin JD, Elastin-derived peptides stimulate trophoblast migration and invasion: a positive feedback loop to enhance spiral artery remodelling, MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med 21 (2015) 95–104. 10.1093/molehr/gau089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Harris LK, Smith SD, Keogh RJ, Jones RL, Baker PN, Knöfler M, Cartwright JE, Whitley G.St.J., Aplin JD, Trophoblast- and vascular smooth muscle cell-derived MMP12 mediates elastolysis during uterine spiral artery remodeling, Am. J. Pathol 177 (2010) 2103–2115. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hiden U, Eyth CP, Majali-Martinez A, Desoye G, Tam-Amersdorfer C, Huppertz B, Ghaffari Tabrizi-Wizsy N, Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 12 is highly specific for non-proliferating invasive trophoblasts in the first trimester and temporally regulated by oxygen-dependent mechanisms including HIF-1A, Histochem. Cell Biol 149 (2018) 31–42. 10.1007/s00418-017-1608-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zhou Y, Chiu K, Brescia RJ, Combs CA, Katz MA, Kitzmiller JL, Heilbron DC, Fisher SJ, Increased depth of trophoblast invasion after chronic constriction of the lower aorta in rhesus monkeys, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 169 (1993) 224–229. 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90172-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kadyrov M, Schmitz C, Black S, Kaufmann P, Huppertz B, Pre-eclampsia and maternal anaemia display reduced apoptosis and opposite invasive phenotypes of extravillous trophoblast, Placenta. 24 (2003) 540–548. 10.1053/plac.2002.0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wakeland AK, Soncin F, Moretto-Zita M, Chang C-W, Horii M, Pizzo D, Nelson KK, Laurent LC, Parast MM, Hypoxia directs human extravillous trophoblast differentiation in a hypoxia-inducible factor–dependent manner, Am. J. Pathol 187 (2017) 767–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Anacker J, Segerer SE, Hagemann C, Feix S, Kapp M, Bausch R, Kämmerer U, Human decidua and invasive trophoblasts are rich sources of nearly all human matrix metalloproteinases, MHR Basic Sci. Reprod. Med 17 (2011) 637–652. 10.1093/molehr/gar033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Espino Y Sosa S, Flores-Pliego A, Espejel-Nuñez A, Medina-Bastidas D, Vadillo-Ortega F, Zaga-Clavellina V, Estrada-Gutierrez G, New insights into the role of matrix metalloproteinases in preeclampsia, Int. J. Mol. Sci 18 (2017). 10.3390/ijms18071448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Plaks V, Rinkenberger J, Dai J, Flannery M, Sund M, Kanasaki K, Ni W, Kalluri R, Werb Z, Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency phenocopies features of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) 11109–11114. 10.1073/pnas.1309561110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Staun-Ram E, Goldman S, Gabarin D, Shalev E, Expression and importance of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and -9) in human trophoblast invasion, Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RBE 2 (2004) 59. 10.1186/1477-7827-2-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system, Nat. Med 9 (2003) 677–684. 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Macklin PS, McAuliffe J, Pugh CW, Yamamoto A, Hypoxia and HIF pathway in cancer and the placenta, Placenta. 56 (2017) 8–13. 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhang J, Chen Z, Smith GN, Croy BA, Natural killer cell-triggered vascular transformation: maternal care before birth?, Cell. Mol. Immunol 8 (2011) 1–11. 10.1038/cmi.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hanna J, Mandelboim O, When killers become helpers, Trends Immunol. 28 (2007) 201–206. 10.1016/j.it.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Sharma S, Natural killer cells and regulatory T cells in early pregnancy loss, Int. J. Dev. Biol 58 (2014) 219–229. 10.1387/ijdb.140109ss. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Guimond MJ, Luross JA, Wang B, Terhorst C, Danial S, Croy BA, Absence of natural killer cells during murine pregnancy is associated with reproductive compromise in TgE26 mice, Biol. Reprod 56 (1997) 169–179. 10.1095/biolreprod56.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Velicky P, Knöfler M, Pollheimer J, Function and control of human invasive trophoblast subtypes: Intrinsic vs. maternal control, Cell Adhes. Migr 10 (2016) 154–162. 10.1080/19336918.2015.1089376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Biadasiewicz K, Fock V, Dekan S, Proestling K, Velicky P, Haider S, Knöfler M, Fröhlich C, Pollheimer J, Extravillous trophoblast-associated ADAM12 exerts pro-invasive properties, including induction of integrin beta 1-mediated cellular spreading, Biol. Reprod 90 (2014) 101. 10.1095/biolreprod.113.115279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Knöfler M, Pollheimer J, IFPA Award in Placentology lecture: molecular regulation of human trophoblast invasion, Placenta. 33Suppl (2012) S55–62. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Pollheimer J, Haslinger P, Fock V, Prast J, Saleh L, Biadasiewicz K, Jetne-Edelmann R, Haraldsen G, Haider S, Hirtenlehner-Ferber K, Knöfler M, Endostatin suppresses IGF-II-mediated signaling and invasion of human extravillous trophoblasts, Endocrinology. 152 (2011) 4431–4442. 10.1210/en.2011-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chakraborty D, Rumi MAK, Konno T, Soares MJ, Natural killer cells direct hemochorial placentation by regulating hypoxia-inducible factor dependent trophoblast lineage decisions, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108 (2011) 16295–16300. 10.1073/pnas.1109478108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ain R, Canham LN, Soares MJ, Gestation stage-dependent intrauterine trophoblast cell invasion in the rat and mouse: novel endocrine phenotype and regulation, Dev. Biol 260 (2003) 176–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sliz A, Locker KCS, Lampe K, Godarova A, Plas DR, Janssen EM, Jones H, Herr AB, Hoebe K, Gab3 is required for IL-2– and IL-15–induced NK cell expansion and limits trophoblast invasion during pregnancy, Sci. Immunol 4 (2019) eaav3866. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Bulmer JN, Lash GE, Human uterine natural killer cells: a reappraisal, Mol. Immunol 42 (2005) 511–521. 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Williams PJ, Searle RF, Robson SC, Innes BA, Bulmer JN, Decidual leucocyte populations in early to late gestation normal human pregnancy, J. Reprod. Immunol 82 (2009) 24–31. 10.1016/j.jri.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Kwan M, Hazan A, Zhang J, Jones RL, Harris LK, Whittle W, Keating S, Dunk CE, Lye SJ, Dynamic changes in maternal decidual leukocyte populations from first to second trimester gestation, Placenta. 35 (2014) 1027–1034. 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Smith SD, Dunk CE, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL, Evidence for immune cell involvement in decidual spiral arteriole remodeling in early human pregnancy, Am. J. Pathol 174 (2009) 1959–1971. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Vassiliadou N, Bulmer JN, Characterization of tubal and decidual leukocyte populations in ectopic pregnancy: evidence that endometrial granulated lymphocytes are absent from the tubal implantation site, Fertil. Steril 69 (1998) 760–767. 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kemp B, Kertschanska S, Handt S, Funk A, Kaufmann P, Rath W, Different placentation patterns in viable compared with nonviable tubal pregnancy suggest a divergent clinical management, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 181 (1999) 615–620. 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Emmer PM, Steegers EAP, Kerstens HMJ, Bulten J, Nelen WLDM, Boer K, Joosten I, Altered phenotype of HLA-G expressing trophoblast and decidual natural killer cells in pathological pregnancies, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 17 (2002) 1072–1080. 10.1093/humrep/17.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tantbirojn P, Crum CP, Parast MM, Pathophysiology of placenta creta: the role of decidua and extravillous trophoblast, Placenta. 29 (2008) 639–645. 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Khong TY, The pathology of placenta accreta, a worldwide epidemic, J. Clin. Pathol 61 (2008) 1243–1246. 10.1136/jcp.2008.055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, Gazit R, Yutkin V, Benharroch D, Porgador A, Keshet E, Yagel S, Mandelboim O, Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface, Nat. Med 12 (2006) 1065–1074. 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wallace AE, Fraser R, Gurung S, Goulwara SS, Whitley GS, Johnstone AP, Cartwright JE, Increased angiogenic factor secretion by decidual natural killer cells from pregnancies with high uterine artery resistance alters trophoblast function, Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl 29 (2014) 652–660. 10.1093/humrep/deu017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Robson A, Harris LK, Innes BA, Lash GE, Aljunaidy MM, Aplin JD, Baker PN, Robson SC, Bulmer JN, Uterine natural killer cells initiate spiral artery remodeling in human pregnancy, FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol 26 (2012) 4876–4885. 10.1096/fj.12-210310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Rätsep MT, Felker AM, Kay VR, Tolusso L, Hofmann AP, Croy BA, Uterine natural killer cells: supervisors of vasculature construction in early decidua basalis, Reprod. Camb. Engl 149 (2015) R91–102. 10.1530/REP-14-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Konno T, Rempel LA, Arroyo JA, Soares MJ, Pregnancy in the brown Norway rat: a model for investigating the genetics of placentation, Biol. Reprod 76 (2007) 709–718. 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Cao TC, Thirkill TL, Wells M, Barakat AI, Douglas GC, Trophoblasts and shear stress induce an asymmetric distribution of ICAM-1 in uterine endothelial cells, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol 59 (2008) 167–181. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Choudhury RH, Dunk CE, Lye SJ, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL, Extravillous trophoblast and endothelial cell crosstalk mediates leukocyte infiltration to the early remodeling decidual spiral arteriole wall, J. Immunol 198 (2017) 4115–4128. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Hannan NJ, Salamonsen LA, CX3CL1 and CCL14 regulate extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules in the trophoblast: Potential roles in human embryo implantation, Biol. Reprod 79 (2008) 58–65. 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Sato Y, Trophoblasts acquire a chemokine receptor, CCR1, as they differentiate towards invasive phenotype, Development. 130 (2003) 5519–5532. 10.1242/dev.00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Sato Y, Platelet-derived soluble factors induce human extravillous trophoblast migration and differentiation: platelets are a possible regulator of trophoblast infiltration into maternal spiral arteries, Blood. 106 (2005) 428–435. 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Kaspi E, Guillet B, Piercecchi-Marti M-D, Alfaidy N, Bretelle F, Bertaud-Foucault A, Stalin J, Rambeloson L, Lacroix O, Blot-Chabaud M, Dignat-George F, Bardin N, Identification of soluble CD146 as a regulator of trophoblast migration: potential role in placental vascular development, Angiogenesis. 16 (2013) 329–342. 10.1007/s10456-012-9317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Strategies for investigating the maternal-fetal interface in the first trimester of pregnancy: What can we learn about pathology?, Placenta. (2017). 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lee CQE, Gardner L, Turco M, Zhao N, Murray MJ, Coleman N, Rossant J, Hemberger M, Moffett A, What Is Trophoblast? A combination of criteria define human first-trimester trophoblast, Stem Cell Rep. 6 (2016) 257–272. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J, Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4, Science. 282 (1998) 2072–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Asanoma K, Rumi MAK, Kent LN, Chakraborty D, Renaud SJ, Wake N, Lee D-S, Kubota K, Soares MJ, FGF4-dependent stem cells derived from rat blastocysts differentiate along the trophoblast lineage, Dev. Biol 351 (2011) 110–119. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Okae H, Toh H, Sato T, Hiura H, Takahashi S, Shirane K, Kabayama Y, Suyama M, Sasaki H, Arima T, Derivation of human trophoblast stem cells, Cell Stem Cell. 22 (2018) 50–63.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Takahashi S, Okae H, Kobayashi N, Kitamura A, Kumada K, Yaegashi N, Arima T, Loss of p57KIP2 expression confers resistance to contact inhibition in human androgenetic trophoblast stem cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1916019116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Ishiuchi T, Ohishi H, Sato T, Kamimura S, Yorino M, Abe S, Suzuki A, Wakayama T, Suyama M, Sasaki H, Zfp281 shapes the transcriptome of trophoblast stem cells and is essential for placental development, Cell Rep. 27 (2019) 1742–1754.e6. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Jaju Bhattad G, Jeyarajah MJ, McGill MG, Dumeaux V, Okae H, Arima T, Lajoie P, Bérubé NG, Renaud SJ, Histone deacetylase 1 and 2 drive differentiation and fusion of progenitor cells in human placental trophoblasts, Cell Death Dis. 11 (2020) 311. 10.1038/s41419-020-2500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Bhattacharya B, Home P, Ganguly A, Ray S, Ghosh A, Islam MR, French V, Marsh C, Gunewardena S, Okae H, Arima T, Paul S, Atypical protein kinase C iota (PKCλ/ι) ensures mammalian development by establishing the maternal-fetal exchange interface, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (2020) 14280–14291. 10.1073/pnas.1920201117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Saha B, Ganguly A, Home P, Bhattacharya B, Ray S, Ghosh A, Rumi MAK, Marsh C, French VA, Gunewardena S, Paul S, TEAD4 ensures postimplantation development by promoting trophoblast self-renewal: An implication in early human pregnancy loss, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (2020) 17864–17875. 10.1073/pnas.2002449117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Cinkornpumin JK, Kwon SY, Guo Y, Hossain I, Sirois J, Russett CS, Tseng H-W, Okae H, Arima T, Duchaine TF, Liu W, Pastor WA, Naive human embryonic stem cells can give rise to cells with a trophoblast-like transcriptome and methylome, Stem Cell Rep. 15 (2020) 198–213. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Gerri C, McCarthy A, Alanis-Lobato G, Demtschenko A, Bruneau A, Loubersac S, Fogarty NME, Hampshire D, Elder K, Snell P, Christie L, David L, Van de Velde H, Fouladi-Nashta AA, Niakan KK, Initiation of a conserved trophectoderm program in human, cow and mouse embryos, Nature. (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2759-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Dong C, Beltcheva M, Gontarz P, Zhang B, Popli P, Fischer LA, Khan SA, Park K-M, Yoon E-J, Xing X, Kommagani R, Wang T, Solnica-Krezel L, Theunissen TW, Derivation of trophoblast stem cells from naïve human pluripotent stem cells, ELife. 9 (2020). 10.7554/eLife.52504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Turco MY, Gardner L, Kay RG, Hamilton RS, Prater M, Hollinshead MS, McWhinnie A, Esposito L, Fernando R, Skelton H, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Sharkey A, Marsh SGE, O’Rahilly S, Hemberger M, Burton GJ, Moffett A, Trophoblast organoids as a model for maternal–fetal interactions during human placentation, Nature. (2018). 10.1038/s41586-018-0753-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Haider S, Meinhardt G, Saleh L, Kunihs V, Gamperl M, Kaindl U, Ellinger A, Burkard TR, Fiala C, Pollheimer J, Mendjan S, Latos PA, Knöfler M, Self-renewing trophoblast organoids recapitulate the developmental program of the early human placenta, Stem Cell Rep. 11 (2018) 537–551. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Cartwright JE, Kenny LC, Dash PR, Crocker IP, Aplin JD, Baker PN, Whitley GSJ, Trophoblast invasion of spiral arteries: a novel in vitro model, Placenta. 23 (2002) 232–235. 10.1053/plac.2001.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Crocker IP, Wareing M, Ferris GR, Jones CJ, Cartwright JE, Baker PN, Aplin JD, The effect of vascular origin, oxygen, and tumour necrosis factor alpha on trophoblast invasion of maternal arteriesin vitro, J. Pathol 206 (2005) 476–485. 10.1002/path.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Lee D-S, Rumi MAK, Konno T, Soares MJ, In vivo genetic manipulation of the rat trophoblast cell lineage using lentiviral vector delivery, Genes. N. Y. N 2000 47 (2009) 433–439. 10.1002/dvg.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R, The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 204 (2011) 193–201. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]