Abstract

Background:

Parabrachial nucleus excitation reduces cortical delta oscillation (0.5–4 Hz) power and recovery time associated with anesthetics that enhance γ-aminobutyric-acid-type-A receptor action. The effects of parabrachial nucleus excitation on anesthetics with other molecular targets, such as dexmedetomidine and ketamine, remain unknown. We hypothesized that parabrachial nucleus excitation would cause arousal during dexmedetomidine and ketamine anesthesia.

Methods:

Using Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs), we excited calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 alpha-positive neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region of adult male rats without anesthesia (9 rats), with dexmedetomidine (low-dose: 0.3 μg·kg−1·min−1 for 45 mins, 8 rats; high-dose: 4.5 μg·kg−1·min−1 for 10 mins, 7 rats), or with ketamine (low-dose: 2 mg·kg−1·min−1 for 30 mins, 7 rats; high-dose: 4 mg·kg−1·min−1 for 15 mins, 8 rats). For control experiments (same rats and treatments), we did not excite DREADDs. We recorded and analyzed the electroencephalogram and anesthesia recovery time.

Results:

Parabrachial nucleus excitation reduced delta power in the prefrontal electroencephalogram with low-dose dexmedetomidine for the 150-minute analyzed period, excepting two brief periods (peak median bootstrapped difference [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] during dexmedetomidine infusion = −6.06 [99% CIs: −12.36 to −1.48] dB, P = 0.007). However, parabrachial nucleus excitation was less effective at reducing delta power with high-dose dexmedetomidine and low- and high-dose ketamine (peak median bootstrapped differences during high-dose [dexmedetomidine, ketamine] infusions = [−1.93, −0.87] dB, 99% CIs = [−4.16 to −0.56, −1.62 to −0.18] dB, P = [0.006, 0.019]; low-dose ketamine had no statistically significant decreases during the infusion). Recovery time differences with parabrachial nucleus excitation were not statistically significant for dexmedetomidine (median difference for [low, high] dose = [1.63, 11.01] mins, 95% CIs = [−20.06 to 14.14, −20.84 to 23.67] mins, P = [0.945, 0.297]) nor low-dose ketamine (median difference = 12.82 [95% CIs: −3.20 to 39.58] mins, P = 0.109) but were significantly longer for high-dose ketamine (median difference = 11.38 [95% CIs: 1.81 to 24.67] mins, P = 0.016).

Conclusions:

These results suggest that the effectiveness of parabrachial nucleus excitation to change the neurophysiologic and behavioral effects of anesthesia depends on the anesthetic’s molecular target.

Introduction

Despite many advances in recent decades, the mechanisms of general anesthesia-induced unconsciousness remain incompletely understood.1 One challenge of understanding the mechanisms of anesthesia is that a variety of drugs, with differing molecular and neural circuit targets, each produce the common endpoint of reversible unconsciousness. Among these drugs are propofol, sevoflurane, and isoflurane, each of which potentiate γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors; dexmedetomidine, an α2A-adrenergic receptor agonist; and ketamine, which is primarily an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist.

Despite their differing targets, each of these drugs induces delta oscillations (0.5–4 Hz) in the cortical electroencephalogram (EEG). Previous studies have shown that excitation of subcortical arousal areas can be effective at reducing the neural oscillations and behavioral sedation associated with sleep2–4 or γ-aminobutyric acid-mediated (GABAergic) anesthetics.5–11 Similarly, delta oscillations and recovery times from GABAergic anesthetics can be reduced by increasing the amounts of arousal-area-associated neurotransmitters (or comparable agonists)—acetylcholine (carbachol), norepinephrine, or dopamine—in the brain.12–16 These findings suggest that these anesthetics may act, at least in part, on endogenous sleep/wake neural circuitry to disrupt consciousness.17 One such arousal area, the parabrachial nucleus, is primarily composed of glutamatergic neurons and projects to the basal forebrain, amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, and cortex.18,19 Stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus reduces delta oscillation power and promotes arousal during or following administration of propofol, isoflurane, or sevoflurane.5,8,10 These GABAergic anesthetics are thought to inhibit the parabrachial nucleus and its cortical and subcortical targets, leading to the hypothesis that stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus overcomes the anesthetics’ inhibitory effects, promoting neurophysiologic and behavioral arousal.

The effects of parabrachial nucleus stimulation with other anesthetics, such as dexmedetomidine and ketamine, have not yet been described. Some evidence suggests that dexmedetomidine binds to autoreceptors located presynaptically on locus coeruleus neurons, inhibiting norepinephrine release and disinhibiting the pre-optic area.20,21 Since the pre-optic area, in turn, inhibits ascending arousal areas, including the parabrachial nucleus, the result is sedation. Other evidence conflicts with this hypothesis,22–24 and the mechanisms of dexmedetomidine-induced sedation are still being investigated. Ketamine, on the other hand, may inhibit the parabrachial nucleus25 and its targets, such as the basal forebrain and thalamus,18,19 via its antagonism of NMDA receptors.26 Simultaneously, ketamine is thought to cause excitation of cortical pyramidal neurons by inhibition of GABAergic interneurons.27,28 Because the parabrachial nucleus is a target of the preoptic area and a major, glutamatergic arousal nucleus, we hypothesized that parabrachial nucleus stimulation could elicit signs of arousal during both dexmedetomidine- and ketamine-induced unconsciousness. In order to determine the role of this nucleus, we used Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) to selectively stimulate putative glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region of male rats during dexmedetomidine and ketamine anesthesia.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All surgical and experimental protocols were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, and the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines were followed. Numbers of subjects for experiments were chosen based on previously published studies of parabrachial nucleus stimulation during anesthesia.5,8,10 Thirteen adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were fed ad libitum and housed in rooms with a 12-hour light-dark cycle, with lights on at 7 am and off at 7 pm. All experiments without anesthesia and all anesthesia infusions were completed during the lights-on hours (though some recordings following anesthesia infusions continued past 7 pm). As previous studies used male rodents to examine the effects of parabrachial nucleus stimulation during anesthesia,2,5,8,10 we also used male rats.

Surgery

Male rats (~10 weeks old, 312.5 to 409.5 g) were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane followed by maintenance at 2.5% isoflurane (Henry Schein, Melville, NY) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (Model 942, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). The animal’s body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a heating pad (50-7220F, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). After opening the skin and clearing connective tissue from the top of the skull, craniotomies were made bilaterally over the parabrachial nucleus using a microdrill (Patterson Dental Supply Inc., Wilmington, MA) (see fig. 1A for a schematic of craniotomies). A glass micropipette (5-000-1010, Drummond, Broomall, PA), adapter (MPH6S10, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), and Hamilton syringe (80301, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV) containing the virus (2.8×1012 viral genomes/mL, diluted from 2.8×1013 viral genomes/mL using saline; pAAV-CaMKIIa-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry; Addgene, Watertown, MA) for DREADDs transfection was lowered down to the parabrachial nucleus (stereotaxic coordinates, relative to Bregma: −8.0 to −9.06 mm posterior; ±1.96 to ±2.0 mm lateral; −7.2 mm ventral), and 500 nL of virus per side was delivered via microinjection pump (53311, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). Three craniotomies were also made over the left prefrontal cortex (2.2 mm posterior; −2.2 mm lateral), left parietal cortex (−3.84 mm posterior; −2.2 mm lateral), and cerebellum (in the middle of the interparietal bone for a reference EEG), and stainless steel EEG electrodes (791400, A-M Systems, Sequim, WA) were hooked just under the skull at each craniotomy. Finally, holes were drilled for a ground screw over the cerebellum and bone screws (51457, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) to support the implant. Stainless steel electromyography (EMG) electrodes (793500, A-M Systems, Sequim, WA) were inserted for recording nuchal muscle activity. EEG and EMG electrodes were all connected to a Neuralynx electrode interface board (EIB-8, Neuralynx, Bozeman, Montana), and the electrodes and electrode interface board were secured to the skull and bone screws with dental cement. Following surgery, rats were given analgesics (ketoprofen, 4 mg/kg; Ketofen, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) and allowed to rest for at least 14 days before beginning experiments. This allowed for recovery from surgery and expression of DREADDs. In addition to 10 rats that received the full surgery, three rats were given viral injections only (≤500 nL per side; no EEG/EMG electrode implantation) for histological verification of DREADDs effectiveness and specificity of expression.

Fig. 1.

Overview of EEG electrode locations and DREADDs expression. (A) Schematic of the parabrachial nucleus injection, EEG electrode, and bone screw sites on an overhead view of the rat skull. (B) Image showing expression of DREADDS in a coronal slice including the parabrachial nucleus region. (C) Outlines of DREADDs expression in the 10 male rats used for the EEG recordings in this study on two different coronal atlas slices including the parabrachial nucleus. Each color indicates a different animal. (D-E) Immunofluorescence images showing colocalization of c-Fos and DREADDs following saline (D) and clozapine-N-oxide (E) injections. 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) expression shows cell nuclei in the parabrachial nucleus region. mCherry, a red fluorescent protein, is co-expressed with DREADDs in DREADDs-transfected neurons. Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence (green) shows expression of c-Fos, indicating excited neurons. Merged images show c-Fos expression in mCherry+ (DREADDs+) neurons, indicated by white arrows. (F) Immunofluorescence image showing colocalization of CaMKIIa and DREADDs. Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence (green) shows expression of CaMKIIa, a marker of glutamatergic neurons. Merged image shows mCherry (DREADDs) expression in CaMKIIa+ neurons, indicated by white arrows.

Chemogenetics

The excitatory DREADD hM3Dq was used to selectively excite calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-positive (CaMKIIa+) neurons. hM3Dq is a muscarinic receptor modified to be sensitive to the exogenous ligand clozapine-N-oxide, instead of acetylcholine.29 We used an adeno-associated virus (AAV8 serotype) that contained a plasmid with a promoter specific to CaMKIIa+ (putative glutamatergic) neurons, followed by the genes for hM3Dq and mCherry, a fluorescent tag (pAAV-CaMKIIa-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry; Addgene, Watertown, MA). Using this virus enabled us to constrain expression of hM3Dq to CaMKIIa+ neurons transfected by the virus.

Data acquisition

EEG (filtered 0.1–500 Hz) and EMG (filtered 10–500 Hz) signals were acquired using a Neuralynx Digital Lynx SX recording system at a sampling rate of 500 Hz (Neuralynx Inc., Bozeman, Montana). Overhead video recordings were also captured to assess behavioral states.

Study design

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus on arousal during dexmedetomidine and ketamine anesthesia. Five anesthesia conditions were paired with saline and clozapine-N-oxide injections (for a total of 10 treatment groups): (1) no anesthesia, (2) low-dose dexmedetomidine (0.3 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 45 mins), (3) high-dose dexmedetomidine (4.5 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 10 mins), (4) low-dose ketamine (2 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 30 mins), and (5) high-dose ketamine (4 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 15 mins). Each of the subjects of a given anesthesia condition received both clozapine-N-oxide and saline injections, in separate experiments, allowing us to compare between clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions for each rat. Randomization methods were not used to determine which treatments each rat received or the order in which the treatments (anesthetics or clozapine-N-oxide/saline) were received, but the order of experiments was varied between rats (see Supplemental Digital Content table S1 for experiment orders for each rat).

For experiments without anesthesia, intraperitoneal injections of clozapine-N-oxide (HY-17366, MedChem Express LLC, Princeton, NJ, and 6329/50, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (1 mg/kg) or saline were given within the half-hour range between 11:23 and 11:53 am. EEG and EMG were then recorded for 5 hours after the injection. For these experiments without anesthesia, rats were allowed to rest for at least three days between experiments if clozapine-N-oxide was given in the first of the two experiments and at least one day if saline was given first.

For experiments with anesthesia, prior to starting recordings, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane for ~15 minutes to place an intravenous port in the lateral tail vein. Immediately following cessation of isoflurane, clozapine-N-oxide (or saline) intraperitoneal injections were administered. One hour after the clozapine-N-oxide (or saline) injection, dilutions of dexmedetomidine (2 μg/mL for low-dose or 5 μg/mL for high-dose) (Dexmedetomidine Hydrochloride Injection, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Mumbai, India, and Dexmedetomidine Injection, Accord Healthcare, Ahmedabad, India) or ketamine (6 mg/mL) (Ketamine HCl Injection, West-Ward, Eatontown, NJ) in saline were administered intravenously via a syringe pump (HA3000I, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). This time delay allowed for clozapine-N-oxide to reach its maximal effectiveness, which occurs at about 45 minutes after administration.30 Two exceptions to the one-hour delay between clozapine-N-oxide (or saline) and anesthetic infusion occurred: in one high-dose dexmedetomidine experiment (Rat 4), clozapine-N-oxide was injected 140 minutes prior to the start of the anesthetic infusion, and in one high-dose ketamine experiment (Rat 3), saline was injected 116 minutes prior to the start of the anesthetic infusion. Both exceptions were well within the ~9 hour period during which clozapine-N-oxide has been shown to be effective.30 Normothermia was maintained with a heating pad under the recording cage while the animals were anesthetized. EEG and EMG recordings were started a minimum of 10 minutes prior to beginning anesthesia infusion. Rats were allowed to rest for at least three days between all experiments with anesthesia except one high-dose ketamine experiment. Only two days of rest were given prior to that experiment, as it followed an aborted ketamine experiment in which the IV started leaking before the infusion completed. For experiments with anesthesia, recordings continued until the rats recovered from anesthesia and were mobile.

Following completion of each subject’s experiments, rats were euthanized using isoflurane overdose and exsanguination via transcardial perfusion (see Histology subsection). Blinding methods were not used in this study.

Analysis of sleep states

The EEG and EMG signals from experiments without anesthesia were used to visually score wakefulness, non-rapid-eye-movement (non-REM) sleep, and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep in 2 second epochs using Spike2 (CED, Cambridge, UK). The time spent in waking, non-REM, and REM sleep were then separately totaled over the 5 hours following saline or clozapine-N-oxide injections. Each rat’s state was assumed to be awake during the first few minutes following their injection, since it took a few minutes of active handling to plug them into the recording system.

Analysis of recovery times

Just after the anesthetic infusion finished, each rat was turned on its side. Recovery time was measured as the time from the end of the anesthetic infusion to when the rat righted itself and had all four paws on the floor. In five of the low-dose dexmedetomidine experiments, the rats never lost the righting reflex; in such cases, return of movement was used to measure recovery time.

Spectral analysis of EEG data

Data was analyzed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Prior to spectral analysis, the mean of each EEG recording was subtracted from the entire signal. Artifacts were then removed by identifying time points where the voltage crossed a threshold of ±1500 μV. All threshold crossings less than one minute apart were grouped together as a single artifact, with all time points in between treated as threshold crossings. The signal at and surrounding each of these time points was then multiplied by an inverted Hamming window with a length of 0.15 seconds, centered at the identified voltage threshold crossing. In this manner, time points identified as threshold crossings were set to 0 μV, and the signal 0.075 seconds before and after artifacts gradually increased to full magnitude, reducing sharp edges in the signal that would produce harmonics in the spectrogram.

All spectrograms in this study were computed using the multitaper methods described in [31].31 Example spectrograms were computed from 0 to 30 Hz (for experiments without anesthesia) or 0 to 50 Hz (for experiments with anesthesia) using a 30 second window that moved in 3 second steps, a time-half-bandwidth product of 3, and 5 DPSS tapers. The signal in each window was linearly detrended before the multitaper spectrogram was computed. For Supplemental Digital Content figures, the spectrograms were computed from 0 to 60 Hz (to accommodate gamma band analysis) for both experiments with and without anesthesia. Any windows with 0 μV2 total power, such as those comprised solely of removed electrical artifacts, were discarded from the analysis (e.g., see the beginning of the spectrograms in fig. 2A–B, where the artifact time points are given the color of the minimum value in the spectrogram), and power was converted to decibels (dB).

Fig. 2.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region decreased delta oscillations, non-REM, and REM sleep without anesthesia. (A) An example spectrogram shows the spectral power for 0–30 Hz over time in the prefrontal EEG following intraperitoneal injection of saline (top). The EMG from the same experiment shows lack of movement during times with high delta power (bottom) (B) An example spectrogram from the same rat following clozapine-N-oxide injection shows an absence of high delta power (top). The corresponding EMG shows stillness, possibly due to the clozapine-N-oxide injection (bottom; see Discussion). (C) Summary of power differences between conditions over time shows decreased mean delta power for clozapine-N-oxide experiments relative to saline experiments. For all power difference traces in this and subsequent figures, traces represent the median (± 99% CIs) of a bootstrapped collection of 5,000 mean differences. Thus, time points where the CIs (shaded regions) do not overlap with zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence. Time periods that show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence are indicated by black bars above the dashed zero line, representing lower power in the clozapine-N-oxide condition. Saline or clozapine-N-oxide injections were given at time = 0 hrs. (A), (B), and (C) have the same time axes. (D) Comparison of the amount of time spent in waking (left), non-REM (middle), and REM (right) stages between saline and clozapine-N-oxide conditions for the 5 hours following injection. Time spent in waking was longer and time spent in non-REM and REM sleep was shorter with clozapine-N-oxide experiments, relative to saline experiments, in a statistically significant way. *P < 0.05, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB, unless otherwise noted. To measure the power in various frequency bands between conditions over time, the multitaper spectrogram was computed from 0 to 30 Hz (for experiments without anesthesia) or 0 to 50 Hz (for experiments with anesthesia) using a 120 second, non-overlapping time window, a time-half-bandwidth product of 3, and 5 DPSS tapers. The signal in each window was linearly detrended before the multitaper spectrogram was computed. After discarding windows with 0 μV2 total power and conversion to decibels, power in each band (delta: 0.5–4 Hz; theta: 4–8 Hz; alpha: 10–15 Hz; beta: 15–30 Hz; gamma: 40–60 Hz) was averaged for each time point in the spectrogram. This mean power was aligned in time for all rats, relative to the start of anesthesia delivery.

For comparison of mean power in each frequency band between clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions, due to small sample sizes, we used the bootstrapping technique to find CIs. For each time point, the mean spectral power in a given frequency band from the saline condition was subtracted from the corresponding time point’s power in the clozapine-N-oxide condition of the same rat. The differences from all rats for each time point were sampled with replacement N times (where N = the number of subjects), and the mean was taken. This process was repeated 5,000 times for each time point to form a bootstrapped collection of 5,000 mean power differences. From this bootstrapped collection, the overall median for each time point was taken, and 99% CIs were found by taking the range containing 99% of the bootstrapped mean differences. Thus, when then the CIs do not overlap with zero, it indicates 99% confidence that there is a difference between the mean power in that frequency band under clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions. P-values that are reported for times with peak median bootstrapped mean differences in power were calculated by re-running the bootstrap analysis for those time points using the “boot.t.test” function in the MKinfer package (version 0.6) in R (version 4.1.0) (99% confidence level, 5000 bootstrap replicates; reported medians and CIs for peak median bootstrapped differences in power were taken from the MATLAB bootstrap analysis described above). For some figure panels containing bootstrapped mean differences in power (figs. 2C, 3B, 5B, 6B, and the associated Supplemental Digital Content figures), the number of subjects (N) at each time point varies due to occasional electrical artifacts, so ranges of N are reported. For fig. 2C, the first 10 minutes of measurements following clozapine-N-oxide or saline injections (at time = 0) were not used to calculate the reported range of N, as some rats took longer than others to plug into the EEG recording system.

Fig. 3.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region decreased delta oscillations but did not affect recovery time with low-dose dexmedetomidine anesthesia. (A) Example spectrograms showing the spectral power for 0–50 Hz over time in the prefrontal EEG following intraperitoneal injections of saline (top) and clozapine-N-oxide (bottom) in the same rat. Black bar over the spectrograms indicates the time over which the dexmedetomidine infusion (0.3 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 45 mins) took place. Clozapine-N-oxide or saline injections were given an hour before the start of the dexmedetomidine infusion. Solid vertical lines represent the time of recovery for each example experiment. (Note: the transient dip in delta power at the end of dexmedetomidine administration in both [A] and [B] is due to our handling the rat to place it on its side.) Example EEG traces to the right of each spectrogram are bandpass filtered from 0.5–4 Hz and show the reduced delta amplitude with parabrachial nucleus region excitation. The arrow over the spectrograms indicates the time, for both conditions, from which the traces were taken. (B) Summary of power differences over time shows decreased mean delta power for clozapine-N-oxide experiments relative to saline experiments. Time periods that show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence are indicated by black bars above the dashed zero line, representing lower power in the clozapine-N-oxide condition. Spectrograms in (A) and summary power in (B) have the same time axes. (C) No statistically significant differences between conditions were seen in recovery times, as measured by time to return of righting reflex (or return of movement in cases where righting reflex was not lost).

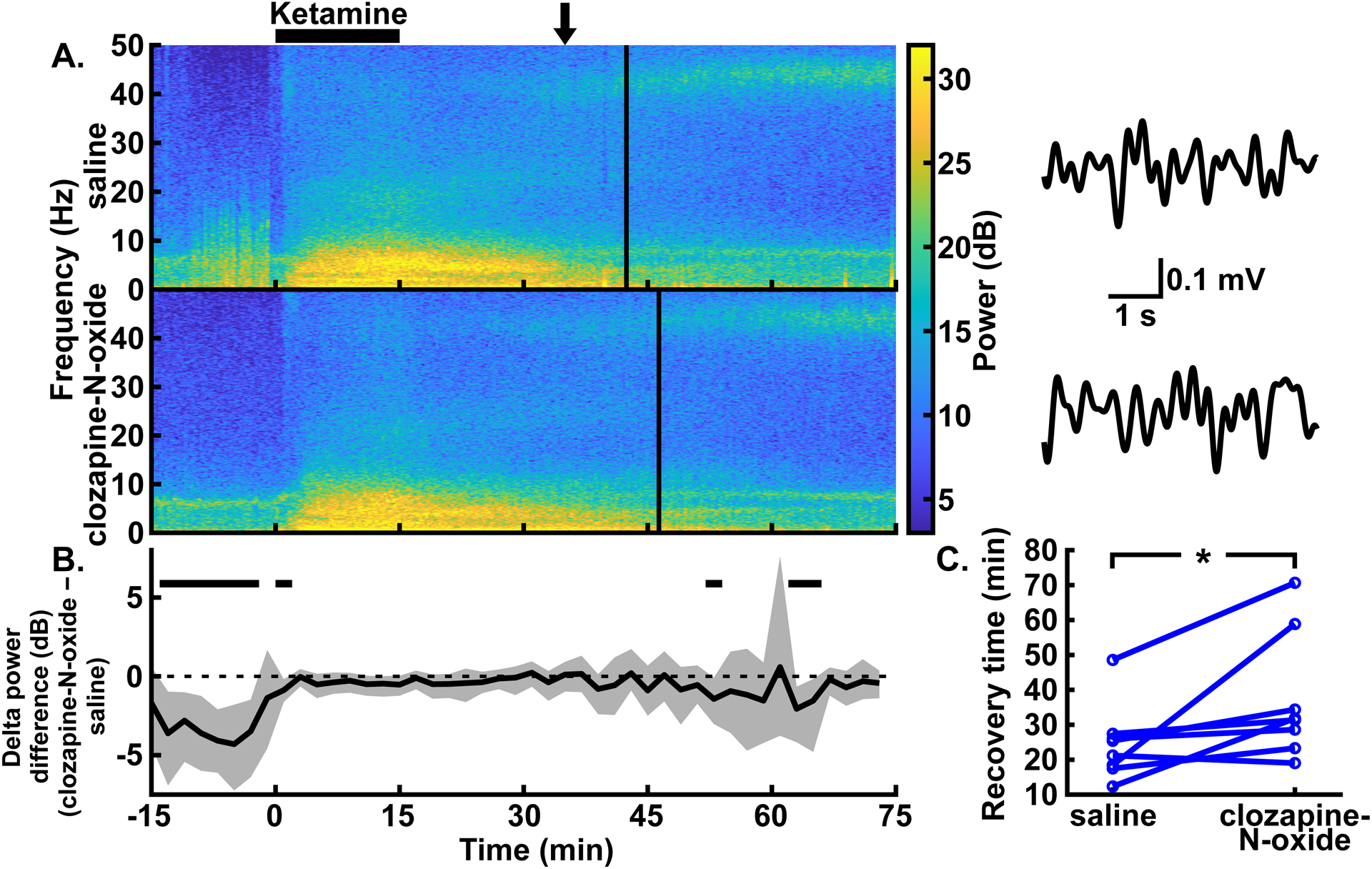

Fig. 5.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region did not affect delta oscillations during, nor recovery time following, low-dose ketamine anesthesia. (A) Example spectrograms showing the spectral power for 0–50 Hz over time in the prefrontal EEG following intraperitoneal injections of saline (top) and clozapine-N-oxide (bottom) in the same rat. Black bar over the spectrograms indicates the time over which the low-dose ketamine infusion (2 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 30 mins) took place. Clozapine-N-oxide or saline injections were given an hour before the start of the ketamine infusion. Solid vertical lines represent the time of recovery for each example experiment. Example EEG traces to the right of each spectrogram are bandpass filtered from 0.5–4 Hz and show similar delta amplitude with and without parabrachial nucleus region excitation. The arrow over the spectrograms indicates the time, for both conditions, from which the traces were taken. (B) Summary of power differences over time shows similar delta power for clozapine-N-oxide and saline experiments during ketamine infusions. Time periods that show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence are indicated by black bars above or below the dashed zero line, representing lower power in the clozapine-N-oxide or saline conditions, respectively. Spectrograms in (A) and summary power in (B) have the same time axes. (C) No statistically significant differences between conditions were seen in recovery times, as measured by time to return of righting reflex.

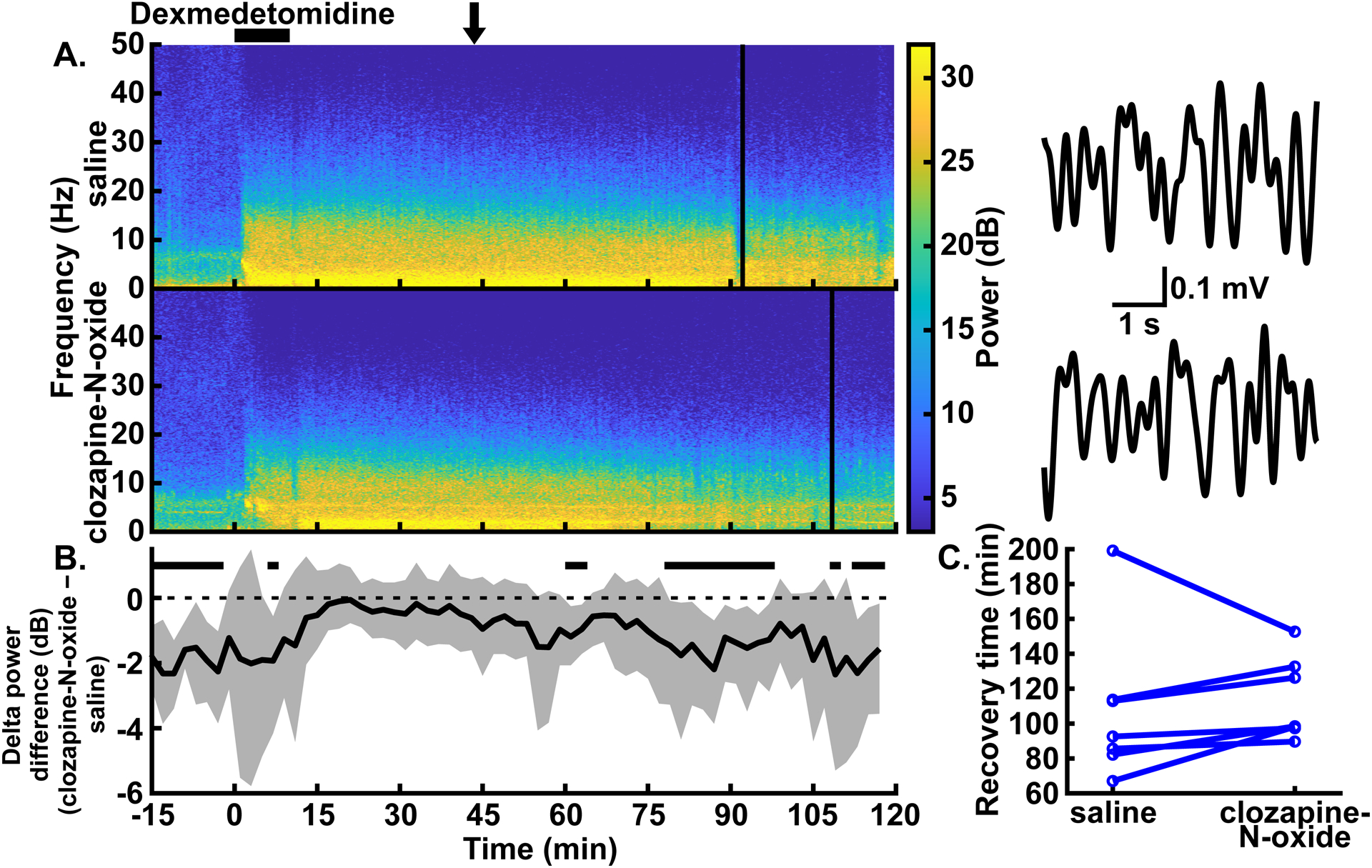

Fig. 6.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region had minor effects on delta oscillations and prolonged recovery time with high-dose ketamine anesthesia. (A) Example spectrograms showing the spectral power for 0–50 Hz over time in the prefrontal EEG following intraperitoneal injections of saline (top) and clozapine-N-oxide (bottom) in the same rat. Black bar over the spectrograms indicates the time over which the high-dose ketamine infusion (4 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 15 mins) took place. Clozapine-N-oxide or saline injections were given prior to the start of the ketamine infusion. Solid vertical lines represent the time of recovery for each example experiment. Example EEG traces to the right of each spectrogram are bandpass filtered from 0.5–4 Hz and show similar delta amplitude with and without parabrachial nucleus region excitation. The arrow over the spectrograms indicates the time, for both conditions, from which the traces were taken. (B) Summary of power differences over time shows similar delta power, other than a few transient decreases, for clozapine-N-oxide experiments relative to saline experiments. Time periods that show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence are indicated by black bars above the dashed zero line, representing lower power in the clozapine-N-oxide condition. Spectrograms in (A) and summary power in (B) have the same time axes. (C) Recovery time from high-dose ketamine anesthesia, as measured by time to return of righting reflex, was longer with clozapine-N-oxide experiments, relative to saline experiments, in a statistically significant way. *P < 0.05, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

For statistical comparison of the time spent in each sleep stage (for experiments without anesthesia) or the recovery times (for experiments with anesthesia), we used R (version 4.1.0). The reported median differences for these measurements are Hodges-Lehmann estimates. Since the same animals received both clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions, we used the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test with an alpha value of 0.05 to determine statistical significance. The Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, the median differences, and the 95% CIs were calculated using the “wilcox.test” function in R.

Histology

Following completion of experiments, rats were euthanized with isoflurane (5%) and transcardially perfused with 1x phosphate-buffered saline, followed by 10% formalin. Brains were then sliced at 50 μm using a vibratome (VT1000 S, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Slices were mounted on a slide with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) containing mounting medium (H-1200-10, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The brain slices were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager.M2, Zeiss, White Plains, NY) to localize expression of mCherry/DREADDs in the parabrachial nucleus region (figs. 1B, 1C).

In addition, immunofluorescence was used in a subset of animals to confirm the effectiveness of DREADDs stimulation and the specificity of DREADDs expression to CaMKIIa+ neurons (fig. 1D–E and 1F, respectively). In order to confirm DREADDs effectiveness, we injected rats with clozapine-N-oxide or saline 60–70 minutes prior to euthanasia. Perfusion and slicing occurred as mentioned above, followed by immunofluorescence. For the immunofluorescence, brain slices were first rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline for 5–10 minutes three times. A solution consisting of 0.1% Triton X-100 (Boston BioProducts, Ashland, MA) in phosphate-buffered saline was used as the bulk solution for a blocking solution containing 10% normal goat serum (ab7481, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and 4% bovine serum albumin (001-000-161, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Slices were placed in this blocking solution for 1 hour. Slices were then incubated overnight at room temperature in blocking solution with an anti-c-Fos primary antibody (1:2000; 226003, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany). Following incubation, slices were rinsed in PBS or 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5–10 minutes three times and then allowed to incubate for 2 hours at room temperature in blocking solution with Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies (1:200; A-11008, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Finally, slices were rinsed twice in 0.1% Triton X-100 and then twice more with phosphate-buffered saline (without Triton X-100) and mounted on a slide with a DAPI containing mounting medium.

In order to confirm the specificity of DREADDs expression to CaMKIIa+ neurons, brain slices were first rinsed in 0.3% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline for 5–10 minutes three times. This solution was used as the bulk solution for a blocking solution containing 10% normal donkey serum (S30-100ML, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA). Slices were placed in the blocking solution for 1 hour. Then, the slices were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking solution with an anti-CaMKIIa primary antibody (1:50; PA5-19128, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following incubation, slices were rinsed in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5–20 minutes three times and then allowed to incubate for 2 hours at room temperature in blocking solution with Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies (1:200; 705-545-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Finally, slices were rinsed twice in 0.3% Triton X-100 and then twice more with phosphate-buffered saline (without Triton X-100) and mounted on a slide with a DAPI containing mounting medium.

All washes and incubations for both immunofluorescence protocols were performed with free-floating brain slices in 12- or 24-well plates placed on a rocker. Colocalization of mCherry, indicating DREADDs expression, and Alexa Fluor 488, indicating c-Fos or CaMKIIa expression, was then visualized using the Zeiss microscope mentioned previously. Neurons with and without colocalized fluorescence were counted using Fiji software.32

Results

We tested the effects of exciting putative glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus by using DREADDs (hM3Dq) and surgically implanted EEG electrodes (fig. 1A). Excitatory DREADDs were expressed in the parabrachial nucleus and in the surrounding region, especially rostral to the parabrachial nucleus (see example expression in fig. 1B and a summary of expression across all 10 rats in two atlas slices in fig. 1C; a summary of mCherry expression across a range of atlas slices is in Supplemental Digital Content fig. S1). Effectiveness of DREADDs stimulation was confirmed by intraperitoneally injecting clozapine-N-oxide, the ligand for DREADDs, and then using immunofluorescence to confirm expression of c-Fos, a marker of neural activity (fig. 1D–E; 4/54 DREADDs+ neurons were c-Fos+ following a saline control injection, N = 1 male rat; 100/124 counted DREADDs+ neurons were c-Fos+ following clozapine-N-oxide injections, N = 2 male rats). The specificity and extent of DREADDs expression in CaMKIIa+ neurons were also confirmed using immunofluorescence (fig. 1F; inside the parabrachial nucleus: 333/383 counted DREADDs+ neurons were CaMKIIa+, and in the same fields-of-view, 333/778 counted CaMKIIa+ neurons were DREADDs+, N = 3 male rats; outside the parabrachial nucleus: 128/173 counted DREADDs+ neurons were CaMKIIa+, and in the same fields-of-view, 128/956 counted CaMKIIa+ neurons were DREADDs+, N = 1 male rat). Thus, by intraperitoneally injecting clozapine-N-oxide, the ligand for DREADDs, we were able to selectively excite CaMKIIa+ neurons during conditions without anesthesia or with dexmedetomidine or ketamine anesthesia.

Some experimental data was not included in our analyses, despite being collected (see grayed-out experiments in Supplemental Digital Content table S1). These included a low-dose ketamine experiment in which the clozapine-N-oxide never fully dissolved (Rat 1) and a high-dose dexmedetomidine experiment in which the rat (Rat 3) was clearly aroused by a neighboring rat’s tail-flick. In addition, two rats experienced issues that prevented them from completing all the planned experiments: Rat 2’s electrode interface board broke during an experiment without anesthesia, and Rat 5 suffered from painful limb swelling that confounded the measurement of recovery time during a low-dose dexmedetomidine experiment. These issues led to the euthanasia of these two rats and thus prevented them from completing the low-dose anesthesia experiments. Two other rats, Rat 8 and Rat 10, were not included in the high-dose dexmedetomidine and high-dose ketamine treatment groups after we felt we had sufficient data to characterize the effects of parabrachial nucleus stimulation during those anesthetics and doses. Finally, after histological analysis, it was found that one rat that was initially included in experiments did not express DREADDs in the parabrachial nucleus and was thus not included in any of our analyses. One other rat did not survive the initial surgery and was not used for any experimental treatment groups.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region reduces delta power without anesthesia

Previous research has shown that non-specific excitation of parabrachial nucleus neurons decreases delta power associated with the awake and non-REM sleep states (indicating neurophysiologic arousal), without anesthesia.2 Since the parabrachial nucleus is primarily glutamatergic, we first tested whether specific excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons also promotes arousal under these conditions. We measured delta power (0.5–4 Hz) in the prefrontal EEG for the first 5 hours following an intraperitoneal injection of clozapine-N-oxide (1 mg/kg). In congruence with the effects of non-specific parabrachial nucleus excitation, we observed reduced delta power relative to control conditions in which intraperitoneal injections of saline were administered to the same rats (fig. 2; trace in fig. 2C summarizes delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections minus delta power with saline injections, and periods with CIs that do not span zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence; peak statistically significant median bootstrapped difference in power [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −6.79 dB, 99% CIs = −9.05 to −4.16 dB, P = 0.001, N = 9 male rats; for entire trace in fig. 2C, N = 8–9 male rats). Whereas the EEG under saline control conditions showed increased delta power, reflecting an increase in sleeping over time, the delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections remained at awake levels. Power in other frequency bands, including theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (10–15 Hz), and beta (15–30 Hz), likewise decreased with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections. Conversely, power in the gamma band (40–60 Hz) increased with clozapine-N-oxide injections (see Supplemental Digital Content fig. S2, which shows the summary power differences [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands).

Moreover, a formal assessment of sleep states during the 5 hours following clozapine-N-oxide injections shows decreased time spent in non-REM and REM sleep relative to experiments with saline injections (fig 2D; median difference in time spent waking [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = 126.31 mins, 95% CIs = 104.13 to 152.31 mins, P = 0.004; median difference in time spent in non-REM sleep [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −117.23 mins, 95% CIs = −137.74 to −99.39 mins, P = 0.004; median difference in time spent in REM sleep [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −9.07 mins, 95% CIs = −15.13 to −2.10 mins, P = 0.004; N = 9 male rats). These results suggest that excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons alone in the parabrachial nucleus region is sufficient to reduce delta power and sleep in male rats without anesthesia, consistent with increased arousal.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region reduces delta power during low-dose, but not high-dose dexmedetomidine anesthesia

Excitation of the parabrachial nucleus, including selective excitation of glutamatergic neurons,8 is effective at reducing both delta oscillations and the time to recovery from isoflurane, sevoflurane, and propofol anesthesia.5,10 We tested whether excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region has similar effects with dexmedetomidine or ketamine. One hour following injection of clozapine-N-oxide, we administered dexmedetomidine (0.3 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 45 mins). We found that delta power in the prefrontal EEG was reduced relative to control experiments in the same rats with saline injections. This reduction was statistically significant between 2 and 40 minutes after the start of the infusion and from 44 minutes until the end of the analyzed period (150 mins) (fig. 3A–B; trace in fig. 3B summarizes delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections minus delta power with saline injections, and periods with CIs that do not span zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence; peak statistically significant median bootstrapped difference in power during dexmedetomidine infusion [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −6.06 dB, 99% CIs = −12.36 to −1.48 dB, P = 0.007, N = 8 male rats; for the entire trace in fig. 3B, N = 7–8 male rats). Consistent with experiments without anesthesia (fig. 2), there was also some statistically significant reduction in delta power prior to the start of anesthesia. Power in theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands likewise decreased with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections. The prevalence of these decreases across the recorded period declined as the frequency of the band increased (i.e., theta > alpha > beta). Conversely, power in the gamma band had slight increases with clozapine-N-oxide injections (see Supplemental Digital Content fig. S3, which shows the summary power differences [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands).

To measure behavioral arousal, we used the time to return of righting reflex (or time to return of movement if righting reflex was not lost; see Methods) as a surrogate for recovery from anesthesia. In contrast to the reduced delta oscillations, the recovery times between clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions did not show statistically significant differences (fig. 3C; median difference [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = 1.63 mins, 95% CIs = −20.06 to 14.14 mins, P = 0.945; N = 8 male rats).

We next sought to understand if excitation of CaMKIIa+ parabrachial nucleus region neurons also reduces delta power effectively at a higher dose of dexmedetomidine. In these experiments, following injection of clozapine-N-oxide, we administered high-dose dexmedetomidine (4.5 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 10 mins). We found that, other than one short period with lower delta power from 6 to 8 minutes, delta power in the prefrontal EEG during the infusion did not show statistically significant differences relative to control experiments in the same rats with saline injections. Following the infusion, periods with lower delta power with parabrachial nucleus region stimulation appeared from 60 to 64 minutes, 78 to 98 minutes, 108 to 110 minutes, and 112 to 118 minutes (fig. 4A–B; trace in fig. 4B summarizes delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections minus delta power with saline injections, and periods with CIs that do not span zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence; peak statistically significant median bootstrapped difference in power during dexmedetomidine infusion [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −1.93 dB, 99% CIs = −4.16 to −0.56 dB, P = 0.006, N = 7 male rats; for the entire trace in fig. 4B, N = 7 male rats). Power in theta, alpha, and beta bands decreased with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections, although to a lesser degree than with low-dose dexmedetomidine. Conversely, power in the gamma band increased after the dexmedetomidine infusion was completed (see Supplemental Digital Content fig. S4, which shows the summary power differences [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands).

Fig. 4.

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region only caused minor reductions in delta oscillations and did not affect recovery time with high-dose dexmedetomidine anesthesia. (A) Example spectrograms showing the spectral power for 0–50 Hz over time in the prefrontal EEG following intraperitoneal injections of saline (top) and clozapine-N-oxide (bottom) in the same rat. Black bar over the spectrograms indicates the time over which the dexmedetomidine infusion (4.5 μg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 10 mins) took place. Clozapine-N-oxide or saline injections were given prior to the start of the dexmedetomidine infusion. Solid vertical lines represent the time of recovery for each example experiment. (Note: the transient dip in delta power at the end of dexmedetomidine administration in both [A] and [B] is due to our handling the rat to place it on its side.) Example EEG traces to the right of each spectrogram are bandpass filtered from 0.5–4 Hz and show similar delta amplitude with and without parabrachial nucleus region excitation. The arrow over the spectrograms indicates the time, for both conditions, from which the traces were taken. (B) Summary of power differences over time shows minor decreases in delta power for clozapine-N-oxide experiments relative to saline experiments. Time periods that show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence are indicated by black bars above the dashed zero line, representing lower power in the clozapine-N-oxide condition. Spectrograms in (A) and summary power in (B) have the same time axes. (C) No statistically significant differences between conditions were seen in recovery times, as measured by time to return of righting reflex.

As with low-dose dexmedetomidine, recovery following high-dose dexmedetomidine infusion, as measured by the return of righting reflex, did not show statistically significant differences for rats with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline controls (fig. 4C; median difference [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = 11.01 mins, 95% CIs = −20.84 to 23.67 mins, P = 0.297; N = 7 male rats).

Excitation of CaMKIIa+ neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region fails to reduce delta power during ketamine anesthesia and increases time to recovery from high-dose ketamine

Given that excitation of CaMKIIa+ parabrachial nucleus region neurons reduced low-dose dexmedetomidine-induced delta power, we next tested whether stimulation of these same neurons could reduce ketamine-induced delta power. In these experiments, one hour following injection of clozapine-N-oxide, we administered ketamine (2 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 30 mins). At this dose, all rats lost righting reflex, though many rats moved when they were placed on their sides (6/7 male rats moved with control conditions; 2/7 male rats moved with clozapine-N-oxide conditions). In contrast with low dose dexmedetomidine, for low-dose ketamine, delta power in the prefrontal EEG during the infusion did not show statistically significant differences relative to control experiments in the same rats with saline injections. Following the infusion, periods with lower delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections appeared from 64 to 68 minutes, 70 to 74 minutes, 78 to 82 minutes, 84 to 86 minutes, 90 to 96 minutes, 110 to 112 minutes, and 114 to 116 minutes. In addition, one brief period with higher delta power appeared from 44 to 46 minutes (fig. 5A–B; trace in fig. 5B summarizes delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections minus delta power with saline injections, and periods with CIs that do not span zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence; for the entire trace in fig. 5B, N = 6–7 male rats). During the ketamine infusion, there was a brief decrease in theta power but no differences in alpha, beta, and gamma power with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections. Following the infusion, theta, alpha, and gamma showed brief periods of decreased power, theta showed a brief increase in power, and beta showed no differences (see Supplemental Digital Content fig. S5, which shows the summary power differences [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands).

Similar to dexmedetomidine, recovery following low-dose ketamine infusion, as measured by the return of righting reflex, did not show statistically significant differences for rats with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline controls (fig. 5C; median difference [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = 12.82 mins, 95% CIs = −3.20 to 39.58 mins, P = 0.109; N = 7 male rats).

When a higher dose of ketamine (4 mg∙kg−1∙min−1 for 15 mins) was used, excitation of CaMKIIa+ parabrachial nucleus region neurons (via clozapine-N-oxide injections) had little effect on delta power in the prefrontal EEG during the infusion, except for a brief reduction in power from 0 to 2 minutes. Following the infusion, periods with lower delta power with parabrachial nucleus region stimulation appeared from 52 to 54 minutes and 62 to 66 minutes (fig. 6A–B; trace in fig. 6B summarizes delta power with clozapine-N-oxide injections minus delta power with saline injections, and periods with CIs that do not span zero show statistically significant differences with 99% confidence; peak statistically significant median bootstrapped difference in power during ketamine infusion [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = −0.87 dB, 99% CIs = −1.62 to −0.18 dB, P = 0.019, N = 8 male rats; for the entire trace in fig. 6B, N = 7–8 male rats). During the ketamine infusion, power in theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands showed no differences with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections. Following the infusion, theta and beta showed brief periods of decreased power, and alpha and beta showed some increased power. No differences were seen in gamma power (see Supplemental Digital Content fig. S6, which shows the summary power differences [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands).

However, contrary to the rest of the anesthesia conditions, recovery following high-dose ketamine infusion, as measured by the return of righting reflex, was longer for rats with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline controls. This elongation of recovery times was statistically significant (fig. 6C; median difference [clozapine-N-oxide – saline] = 11.38 mins, 95% CIs = 1.81 to 24.67 mins, P = 0.016; N = 8 male rats).

Discussion

In this study, the primary outcome was evidence that excitation of putative glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region is sufficient to reduce delta power during low-dose dexmedetomidine anesthesia but not high-dose dexmedetomidine nor ketamine anesthesia. Furthermore, changes in delta power did not correspond to changes in time to recovery from anesthesia. As a secondary outcome, we found that selectively stimulating putative glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus region was sufficient to reduce delta power and time spent in sleep without anesthesia. We also found lesser effects of parabrachial nucleus region stimulation on other frequency bands, including theta, alpha, beta, and gamma, with and without anesthesia. These results advance our understanding of the neural circuit mechanisms underlying EEG patterns under anesthesia and may be useful for improving clinical EEG monitors.

Limitation of using a single biological sex

We used male rats in our study so that our results would be comparable to previous studies that used male rodents to examine the effects of parabrachial nucleus stimulation during anesthesia.2,5,8,10 We cannot rule out, however, that there may be sex differences in the neurophysiologic or behavioral responses to parabrachial nucleus stimulation. Future studies that include both and compare between the sexes are recommended to discern any potential differences.

Limitation of targeting DREADDs to CaMKIIa+ neurons

The extent of colocalization of CaMKIIa expression with glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus has not been studied, so it is not known whether all DREADDs+ neurons in our study were glutamatergic. However, previous studies have shown a strong association between CaMKIIa+ and glutamatergic neurons in the cortex,33,34 amygdala,35 and thalamus36, as well as a strong disassociation between CaMKIIa+ and GABAergic neurons in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and hypothalamus.37 The parabrachial nucleus has also been shown to be primarily glutamatergic18 and express CaMKII.38,39 These previous findings, combined with the large extent of CaMKIIa-driven expression of DREADDs in the parabrachial nucleus in our study, are consistent with the claim that the majority of our DREADDs+ neurons were glutamatergic.

Return of righting reflex as a measure of recovery

In our study, we did not observe any statistically significant reduction in recovery times with clozapine-N-oxide injections relative to saline injections. Contrary to our expectations, we found an increase in time to recovery with excitation of parabrachial nucleus region neurons in the case of high-dose ketamine. This result could indicate a disconnect between neurophysiologic and behavioral indicators of arousal. Indeed, the righting reflex itself does not involve cortical activity,40 and presumably would not directly affect the EEG. However, there are also other possibilities that should be considered. First, due to the arousable nature of low-dose anesthesia (in particular, dexmedetomidine anesthesia) and the large standard deviation of recovery times even under controlled conditions, return of righting reflex can be a variable, albeit common measure of behavioral arousal. In addition, during recovery from dexmedetomidine, although a rat may recover from anesthesia enough to return to the upright position, they usually quickly return to an unconscious state, with the recovery time period lasting far beyond the initial arousal. Finally, in the experiments without anesthesia, a subset of rats showed very little movement following clozapine-N-oxide injection, despite lack of sleep (see example in fig. 2B). This stillness with DREADDs stimulation did not correspond in any obvious way to differences in the anatomical regions expressing DREADDs. However, if this behavior was present as anesthesia began to wear off, it could have confounded the time to recovery results.

Parabrachial nucleus region stimulation has minor effects on theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands

Although not the primary outcome, we also found some differences in theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands with parabrachial nucleus region stimulation. In experiments without anesthesia, reduced amounts of sleep with clozapine-N-oxide injections may be responsible for broadband power reductions affecting theta, alpha, and beta bands, in addition to delta. The reduced amount of sleep with clozapine-N-oxide injections is also consistent with increased gamma power, as gamma power decreases with sleep.41

Power during the dexmedetomidine anesthesia experiments largely follows the same pattern as the sleep experiments. The reductions in theta, alpha, and beta and increase in gamma suggest a similar effect of parabrachial nucleus region stimulation on dexmedetomidine anesthesia and sleep and may underscore similarities in their mechanisms. For ketamine anesthesia experiments, most changes in power occur after the anesthesia infusion has completed and the rats are recovering. Thus, the minor changes that we observed may have more to do with the return of sleeping behavior than on an interaction between parabrachial nucleus region stimulation and ketamine.

Differences in response to parabrachial nucleus region excitation may reflect different delta mechanisms

We found that the ability of CaMKIIa+ neuron excitation in the parabrachial nucleus region to promote arousal during concurrent anesthesia depended on the molecular targets of the anesthetics. In particular, excitation of these neurons reduced delta oscillations during dexmedetomidine (fig. 3), but not ketamine anesthesia (figs. 5, 6). These results may suggest that distinct mechanisms are responsible for delta generation between these two anesthetics.

Anesthetics such as propofol, isoflurane, and sevoflurane, enhance or replicate GABAergic neurotransmission in both subcortical and cortical neurons. As a result, the cortex is inhibited both indirectly, as subcortical arousal nuclei provide less excitatory neurotransmission, and directly, as GABAergic neurotransmission onto cortical neurons is increased.21,26 Like GABAergic anesthetics, dexmedetomidine exerts both indirect and direct effects on the cortex: 1) Dexmedetomidine inhibits norepinephrine release from the locus coeruleus,20 which disinhibits the preoptic area (a sleep-active area), leading to indirect inhibition of other major arousal areas and the cortex. 2) Although less studied, α2A-adrenergic receptors also exist in the cortex,42 and dexmedetomidine may also exert effects on the cortex directly. Similar to the effects of parabrachial nucleus excitation with GABAergic anesthetics, exciting glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus may counteract both the indirect and direct cortical inhibition caused by dexmedetomidine, causing neurophysiologic arousal. This would happen as excitatory, glutamatergic projections from the parabrachial nucleus to other subcortical arousal areas and the cortex are activated. When the inhibition is more profound (as with a high dose of dexmedetomidine), the cortical excitation provided by parabrachial nucleus activation is insufficient to overcome the inhibition (fig. 4).

While ketamine is like GABAergic anesthetics and dexmedetomidine in its inhibition of subcortical arousal areas, it is distinct in its direct cortical effects.21,26 Ketamine is thought to disinhibit cortical neurons and produce an overall excitatory effect on pyramidal neurons via inhibition of local interneurons.27,28,43 Since excitation of the parabrachial nucleus also has an excitatory effect on the cortex, it likely cannot counteract the direct effects of ketamine on the cortex, and thus is ineffective at evoking neurophysiologic arousal. In addition, since ketamine antagonizes NMDA receptors, it may blunt the effects of glutamate release that the parabrachial nucleus provides when excited. It is possible that parabrachial nucleus stimulation may lead to arousal with other doses of ketamine; however, movement was not prevented by the low-dose ketamine we used, so decreasing the dose further would cause insufficient sedation to discern differences between clozapine-N-oxide and saline conditions. Also, as parabrachial nucleus region stimulation did not cause consistent delta power nor recovery time reductions with low-dose or high-dose ketamine, it is unlikely that an even higher dose would be arousable.

Although not examined in this study, it is possible that inhibition of glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus increases cortical delta power or the time to recovery from dexmedetomidine or ketamine anesthesia. Indeed, one recent study showed inhibition of glutamatergic parabrachial nucleus neurons increases time to recovery from sevoflurane.8 However, other studies of parabrachial nucleus excitation have not reported the effects of inhibition on arousal from anesthesia.2,5 The inability of DREADDs techniques to completely silence (rather than just dampen) neural activity can make interpreting results a challenge.44 For this reason, we chose not to investigate the effects of inhibition on arousal from anesthesia.

Finally, the balance between inhibition and excitation can be crucial for determining the oscillatory state of neural circuits.45–48 It is therefore possible that the excitation of glutamatergic neurons in the parabrachial nucleus is effective at disrupting that balance with GABAergic anesthetics and low-dose dexmedetomidine, but it does not disrupt that balance with high-dose dexmedetomidine or ketamine. Consistent with this hypothesis, the parabrachial nucleus projects to the basal forebrain and, accordingly, stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus may cause cortical acetylcholine release. Since dexmedetomidine infusions do not change cortical acetylcholine levels,49 excitation of the parabrachial nucleus may cause unbalanced cortical excitation via an overabundance of acetylcholine, reducing delta power and leading to neurophysiologic arousal. More research, including measurement of cortical neurotransmitters, will be helpful for explaining the mechanisms responsible for the differing responses to excitation of glutamatergic parabrachial nucleus region neurons with these two anesthetics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Statistical support was provided by the Anesthesia Research Center within the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Funding Statement:

Support was provided by the grant P01-GM118269 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Ken Solt is a consultant to Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Hemmings HC, Riegelhaupt PM, Kelz MB, Solt K, Eckenhoff RG, Orser BA, Goldstein PA: Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Anesthetic Mechanisms of Action: A Decade of Discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2019; 40:464–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu MH, Chen MC, Fuller PM, Lu J: Stimulation of the Pontine Parabrachial Nucleus Promotes Wakefulness via Extra-thalamic Forebrain Circuit Nodes. Curr Biol 2016; 26:2301–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR, de Lecea L: VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep-wake behaviors. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19:1356–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta S, Siwek DF: Excitation of the brain stem pedunculopontine tegmentum cholinergic cells induces wakefulness and REM sleep. J Neurophysiol 1997; 77:2975–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo T, Yu S, Cai S, Zhang Y, Jiao Y, Yu T, Yu W: Parabrachial Neurons Promote Behavior and Electroencephalographic Arousal from General Anesthesia. Front Mol Neurosci 2018; 11:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solt K, Van Dort CJ, Chemali JJ, Taylor NE, Kenny JD, Brown EN: Electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area induces reanimation from general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2014; 121:311–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G: Designer receptor manipulations reveal a role of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system in isoflurane general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014; 111:3859–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang TX, Xiong B, Xu W, Wei HH, Qu WM, Hong ZY, Huang ZL: Activation of parabrachial nucleus glutamatergic neurons accelerates reanimation from sevoflurane anesthesia in mice. Anesthesiology 2019; 130:106–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkire MT, McReynolds JR, Hahn EL, Trivedi AN: Thalamic microinjection of nicotine reverses sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex in the rat. Anesthesiology 2007; 107:264–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muindi F, Kenny JD, Taylor NE, Solt K, Wilson MA, Brown EN, Van Dort CJ: Electrical stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus induces reanimation from isoflurane general anesthesia. Behav Brain Res 2016; 306:20–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor NE, Van Dort CJ, Kenny JD, Pei J, Guidera JA, Vlasov KY, Lee JT, Boyden ES, Brown EN, Solt K: Optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area induces reanimation from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113:12826–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pal D, Dean JG, Liu T, Li D, Watson CJ, Hudetz AG, Mashour GA: Differential Role of Prefrontal and Parietal Cortices in Controlling Level of Consciousness. Curr Biol 2018; 28:2145–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solt K, Cotten JF, Cimenser A, Wong KFK, Chemali JJ, Brown EN: Methylphenidate actively induces emergence from general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2011; 115:791–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chemali JJ, Van Dort CJ, Brown EN, Solt K: Active emergence from propofol general anesthesia is induced by methylphenidate. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:998–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenny JD, Chemali JJ, Cotten JF, Van Dort CJ, Kim SE, Ba D, Taylor NE, Brown EN, Solt K: Physostigmine and Methylphenidate Induce Distinct Arousal States during Isoflurane General Anesthesia in Rats. Anesth Analg 2016; 123:1210–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenny JD, Taylor NE, Brown EN, Solt K: Dextroamphetamine (but not atomoxetine) induces reanimation from general anesthesia: Implications for the roles of dopamine and norepinephrine in active emergence. PLoS One 2015; 10:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelz MB, García PS, Mashour GA, Solt K: Escape From Oblivion: Neural Mechanisms of Emergence From General Anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2019; 128:726–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller PM, Sherman D, Pedersen NP, Saper CB, Lu J: Reassessment of the structural basis of the ascending arousal system. J Comp Neurol 2011; 519:933–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulwiler CE, Saper CB: Subnuclear organization of the efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res Rev 1984; 7:229–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson LE, Franks NP, Maze M, Lu J, Guo T, Saper CB: The α2-Adrenoceptor Agonist Dexmedetomidine Converges on an Endogenous Sleep-promoting Pathway to Exert Its Sedative Effects. Anesthesiology 2003; 98:428–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown EN, Purdon PL, Van Dort CJ: General Anesthesia and Altered States of Arousal: A Systems Neuroscience Analysis. Annu Rev Neurosci 2011; 34:601–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarren HS, Chalifoux MR, Han B, Moore JT, Meng QC, Baron-Hionis N, Sedigh-Sarvestani M, Contreras D, Beck SG, Kelz MB: α2-Adrenergic stimulation of the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus destabilizes the anesthetic state. J Neurosci 2014; 34:16385–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Ferretti V, Güntan I, Moro A, Steinberg EA, Ye Z, Zecharia AY, Yu X, Vyssotski AL, Brickley SG, Yustos R, Pillidge ZE, Harding EC, Wisden W, Franks NP: Neuronal ensembles sufficient for recovery sleep and the sedative actions of α2 adrenergic agonists. Nat Neurosci 2015; 18:553–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu FY, Hanna GM, Han W, Mardini F, Thomas SA, Wyner AJ, Kelz MB: Hypnotic hypersensitivity to volatile anesthetics and dexmedetomidine in dopamine β-hydroxylase knockout mice. Anesthesiology 2012; 117:1006–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boon JA, Milsom WK: NMDA receptor-mediated processes in the Parabrachial/Kölliker fuse complex influence respiratory responses directly and indirectly via changes in cortical activation state. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2008; 162:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown EN, Pavone KJ, Naranjo M: Multimodal general anesthesia: Theory and practice. Anesth Analg 2018; 127:1246–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homayoun H, Moghaddam B: NMDA Receptor Hypofunction Produces Opposite Effects on Prefrontal Cortex Interneurons and Pyramidal Neurons. J Neurosci 2007; 27:11496–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali F, Gerhard DM, Sweasy K, Pothula S, Pittenger C, Duman RS, Kwan AC: Ketamine disinhibits dendrites and enhances calcium signals in prefrontal dendritic spines. Nat Commun 2020; 11:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melonakos ED, Moody OA, Nikolaeva K, Kato R, Nehs CJ, Solt K: Manipulating Neural Circuits in Anesthesia Research. Anesthesiology 2020; 133:19–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, Nonneman RJ, Hartmann J, Moy SS, Nicolelis MA, McNamara JO, Roth BL: Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron 2009; 63:27–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prerau MJ, Brown RE, Bianchi MT, Ellenbogen JM, Purdon PL: Sleep Neurophysiological Dynamics Through the Lens of Multitaper Spectral Analysis. Physiology 2017; 32:60–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A: Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012; 9:676–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones EG, Huntley GW, Benson DL: Alpha calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II selectively expressed in a subpopulation of excitatory neurons in monkey sensory-motor cortex: Comparison with GAD-67 expression. J Neurosci 1994; 14:611–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou DJ, Greer CA, Firestein S: Expression pattern of αCaMKII in the mouse main olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol 2002; 443:226–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald AJ, Muller JF, Mascagni F: GABAergic innervation of alpha type II calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase immunoreactive pyramidal neurons in the rat basolateral amygdala. J Comp Neurol 2002; 446:199–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu XB, Jones EG: Localization of alpha type II calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase at glutamatergic but not γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) synapses in thalamus and cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93:7332–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson DL, Isackson PJ, Hendry SHC, Jones EG: Differential gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase and type II calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in basal ganglia, thalamus, and hypothalamus of the monkey. J Neurosci 1991; 11:1540–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Zhang C, Szábo G, Sun QQ: Distribution of CaMKIIα expression in the brain in vivo, studied by CaMKIIα-GFP mice. Brain Res 2013; 1518:9–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermanson O, Larhammar D, Blomqvist A: Preprocholecystokinin mRNA-expressing neurons in the rat parabrachial nucleus: Subnuclear localization, efferent projection, and expression of nociceptive-related intracellular signaling substances. J Comp Neurol 1998; 400:255–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenzel DG, Lal H: The relative reliability of the escape reaction and righting-reflex sleeping times in the mouse. J Am Pharm Assoc 1959; 48:90–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adamantidis AR, Gutierrez Herrera C, Gent TC: Oscillating circuitries in the sleeping brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019; 20:746–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheinin M, Lomasney JW, Hayden-Hixson DM, Schambra UB, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Fremeau RT: Distribution of alpha2-adrenergic receptor subtype gene expression in rat brain. Mol Brain Res 1994; 21:133–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seamans J: Losing inhibition with ketamine. Nat Chem Biol 2008; 4:91–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith KS, Bucci DJ, Luikart BW, Mahler SV: DREADDs: Use and application in behavioral neuroscience. Behav Neurosci 2016; 130:137–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melonakos ED, White JA, Fernandez FR: A model of cholinergic suppression of hippocampal ripples through disruption of balanced excitation/inhibition. Hippocampus 2019; 29:773–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niethard N, Hasegawa M, Itokazu T, Oyanedel CN, Born J, Sato TR: Sleep-Stage-Specific Regulation of Cortical Excitation and Inhibition. Curr Biol 2016; 26:2739–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haider B, Duque A, Hasenstaub AR, McCormick DA: Neocortical network activity in vivo is generated through a dynamic balance of excitation and inhibition. J Neurosci 2006; 26:4535–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dehghani N, Peyrache A, Telenczuk B, Le Van Quyen M, Halgren E, Cash SS, Hatsopoulos NG, Destexhe A: Dynamic Balance of Excitation and Inhibition in Human and Monkey Neocortex. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nemoto C, Murakawa M, Hakozaki T, Imaizumi T, Isosu T, Obara S: Effects of dexmedetomidine, midazolam, and propofol on acetylcholine release in the rat cerebral cortex in vivo. J Anesth 2013; 27:771–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.