Abstract

Objective:

A scoping review surveyed the evidence landscape for studies that assessed outcomes of treating opioid use disorder (OUD) patients with methadone in office-based settings.

Methods:

Ovid MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews databases were searched and reference lists were reviewed to identify additional studies. Studies were eligible if they focused on methadone treatment in office-based settings conducted in the United States or other highly developed countries and reported outcomes (e.g., retention in care). Randomized trials and controlled observational studies were prioritized; uncontrolled and descriptive studies were included when stronger evidence was unavailable. One investigator abstracted key information; a second verified data. A scoping review approach broadly surveyed the evidence; study quality, therefore, was not rated formally.

Results:

We identified 17 studies of patients treated with office-based methadone, including 6 trials, 7 observational studies, and 4 additional papers discussing use of pharmacies to dispense methadone. Studies on office-based methadone, including primary care-based dispensing, were limited but consistently found that stable methadone patients valued office-based care, remained in care with low rates of drug use; outcomes were similar compared to stable patients in regular care. Office-based methadone was associated with higher treatment satisfaction and quality of life. Limitations include underpowered comparisons and small samples.

Conclusions.

Limited research suggests that office-based methadone and pharmacy dispensing could enhance access to methadone treatment for patients with OUD without adversely impacting patient outcomes, and, potentially, inform modifications to federal regulations. Research should assess the feasibility of office-based care for less stable patients.

In the United States (U.S.), federal regulations (Chapter 43 Code of Federal Regulations Part 8) (42 CFR Part 8) for opioid treatment programs (OTPs) require accreditation by organizations approved by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]), adherence to SAMHSA’s standards of care and certification from SAMHSA (1). State regulations may also influence the delivery of care in OTPs (2). Due to Federal legislation and regulations, methadone is only dispensed in federally certified OTPs for treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD).

Restriction of methadone dispensing to OTPs reduces access to potentially lifesaving opioid agonist therapy. Individuals living in rural areas tend to have lengthy commutes to OTPs which are primarily located in metropolitan settings (3). Daily dosing requirements further inhibit access to care. Because pharmacies dispense methadone prescribed for pain indications, using pharmacies to dispense methadone to OTP patients could facilitate access to opioid agonist therapy in rural communities (4, 5).

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000) amended federal statutes to permit office-based treatment with buprenorphine and facilitate access to opioid agonist therapy; office-based care is not generally permitted for methadone. A 2018 New England Journal of Medicine commentary advocated for amendments to the Controlled Substances Act to allow buprenorphine waivered physicians to prescribe methadone for opioid use disorder (OUD) and manage the patients in their primary care practices with methadone dispensed in pharmacies (6). This is standard practice in many countries (7).

Office-based methadone (also known as “methadone medical maintenance”) for stable patients can occur with SAMHSA approved exceptions if the physician’s office is affiliated with an OTP (8). Routine use of office-based methadone, however, is uncommon. To assess harms benefits and feasibility of office-based methadone treatment, we conducted a scoping review (9, 10) to systematically survey the evidence landscape, and highlight studies that assessed outcomes of treating OUD patients with methadone in primary care settings and other office-based settings and/or with pharmacy dispensing for patients.

Methods

Search Strategies.

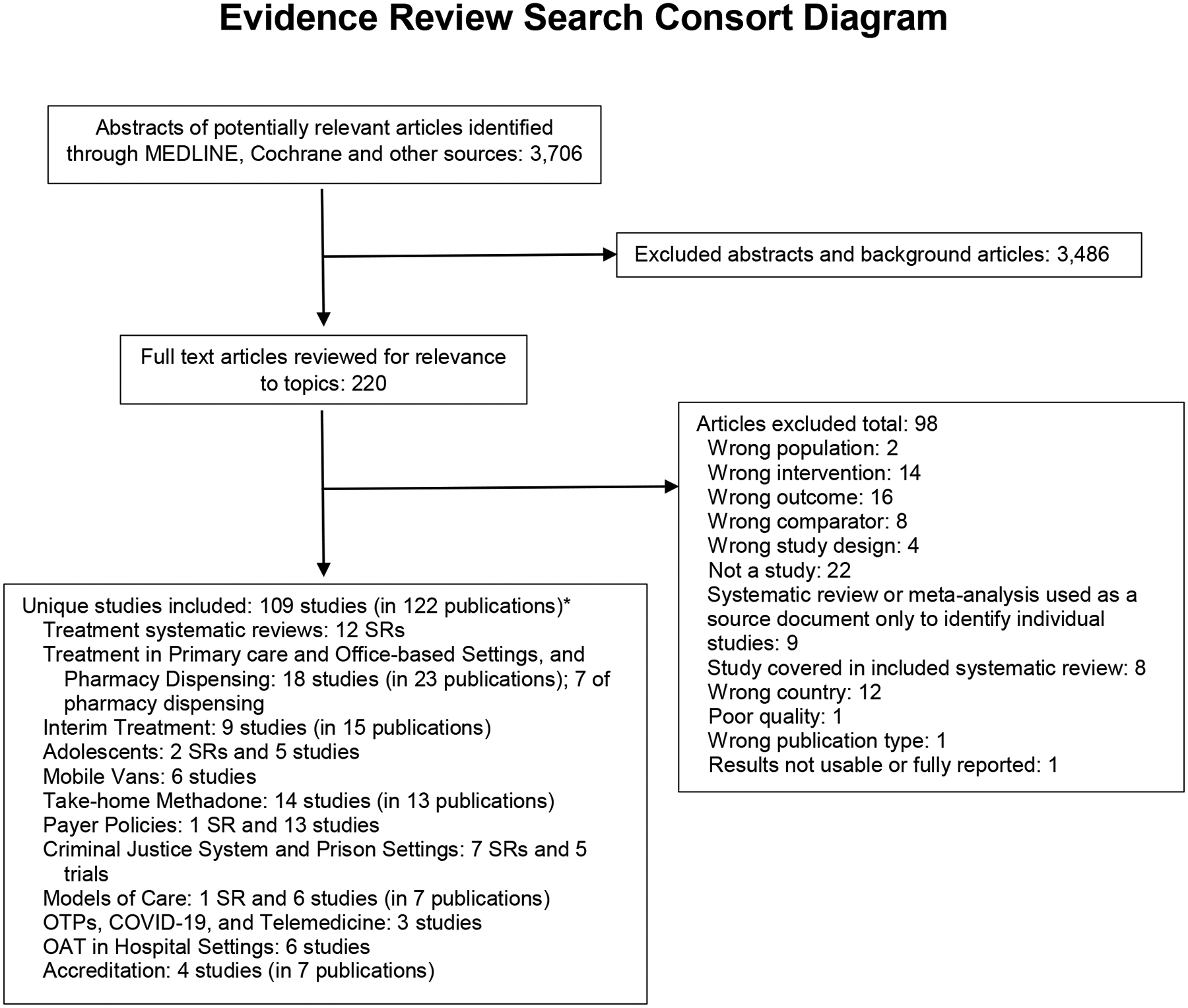

We searched Ovid MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews databases from inception to July 2020. See Supplement Table 1 for a description of the search strategies. We also reviewed reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional studies. The analysis was conducted as part of a larger scoping review of policy research on methadone treatment for OUD that covered additional research areas, (See topics listed in Figure 1) (11). The current analysis focuses on the literature on methadone in office-based settings and U.S. studies of pharmacy dispensing of methadone.

Figure 1: Methadone Tree Consort Diagram for the Scoping Search.

(Selection of papers specific to this paper is highlighted. Other topics included in the larger evidence review are also listed.)

*Some included studies pertain to more than one topic area; the total is the count of unique studies across all topic areas.

Abbreviations: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; OAT = opioid agonist therapy; OTPs = opioid treatment programs; SRs = systematic reviews.

Study Selection.

Studies were selected using a hierarchical approach. Randomized trials and controlled observational were prioritized; observational and descriptive studies were included when the priority evidence was unavailable. Studies addressing methadone policy were eligible if they focused on office-based settings and included outcomes (e.g., treatment initiation, treatment receipt, retention in care, drug use), and were conducted in the U.S. or other highly developed countries. One investigator abstracted key information (clinical setting, country, sample size, intervention/comparison, and main findings) into a Table and a second investigator verified data. Because this was a scoping review that broadly surveyed relevant literature, we used a descriptive approach to summarize the literature and did not formally synthesize or grade the quality of the evidence. The literature flow diagram is available in Figure 1.

Results

We identified 18 studies of patients treated with office-based methadone in 23 publications, including six trials (with eight publications) (12–19), eight observational studies (with 11 publications) (20–30), and 4 descriptive studies (4, 5, 31, 32) (see Table 1). Four randomized trials (with seven publications) (12–17, 30) were conducted in the U.S. (sample sizes varied between n=26 to n=136), and two more trials were conducted in France (n=221) (18) and Australia (n=136) (19). Six observational studies (reported in nine publications) were U.S.-based. One group of medical methadone patients was reported in four publications; sample sizes increased from 28 to 156 participants and follow-up increased from 1 to 15 years (23–26). The other U.S. observational studies had sample sizes from 10 to 127 participants (20–23, 27). Three non-U.S. observational studies included analyses from the United Kingdom (n= 240; n=400) (28, 32) and Ireland (29). One trial (16, 17) and three observational studies (20–22) of office-based methadone utilized pharmacy dispensing, in addition, pharmacy dispensing was addressed in four additional descriptive studies.(4, 5, 31, 32)

Table 1.

Office-based methadone and pharmacy studies

| Author, Year | Design N | Setting Country | Intervention | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.-based Randomized Clinical Trials | |||||

| Fiellin 2001(12) | RCT N=46 SAMHSA and DEA exceptions | Office-based primary care New Haven, CT | To compare methadone opioid agonist therapy in primary care versus OTP in stabilized patients on methadone A: Primary care methadone dispensed in office (n=22) B: OTP methadone opioid agonist therapy (n=24) | Similar rates of illicit drug use, functional status, and use of health, legal, or social services; primary care methadone maintenance more likely to be rated excellent by patients | Small samples |

| King 2006 (13) 12-month follow-up results for King 2002 | RCT N=92 SAMHSA and DEA exceptions | Primary care, office-based specialty setting vs OTP Baltimore, U.S. | A: Methadone in office-based setting with 27 take-homes (n=33) B: Methadone in OTP with 27 take-homes (n=32) C: Usual methadone in OTP (n=27) |

Low rates of drug use or failed medication recall, treatment satisfaction high in all groups Methadone patients initiated more new employment or family/social activities than usual methadone | Small samples |

| King 2002 (14) Same study as King 2006 with fewer study participants and six months of follow-up | N=73 | Same as above | Same as above | Six months of follow-up. Overall, 1% of urine specimens positive for illicit drugs, no evidence of methadone diversion, and low rates of medication misuse. | |

| Senay 1993 (15) | RCT N=130 FDA IND | Office-based specialty setting U.S. | A: Medical methadone in office-based setting (n=89) B: usual methadone in OTP (n=41). OTP dispensed methadone for both patient groups. |

Retention 73% for medical methadone vs. 73% for usual methadone treatment in OTP at 1 year. Addiction severity similar in both groups at 1 year. No difference in positive urine toxicology screens | Small sample, dated study |

| Tuchman 2008 (16) Tuckman 2006 (17) | RCT N=26 SAMHSA and DEA exceptions | Primary care Santa Fe and Albuquerque, NM, U.S. | A: Medical methadone in primary care setting (physician office, community pharmacy, and social work) (n=14; analyzed 13) versus B: Methadone in OTP (n=12; analyzed 9) |

At 12 months, retention 100% vs. 89%, illicit opiate use 23% vs. 78%, urine toxicology positive for cocaine 23% vs. 44%, urine toxicology positive for benzodiazepines 8% vs. 44% | Small samples, women only, loss to follow-up, allowed participants to switch conditions following randomization. |

| Non-U.S. Randomized Clinical Trials | |||||

| Carrieri 2014 (18) | RCT N=221 | Primary care or specialty care in France. Methadone dispensed at pharmacies for patients in primary care | A: Methadone induction in primary care (n=155) B: Methadone induction in specialty care (n=66) |

Methadone induction in primary feasible and acceptable to physicians and patients, and similar to induction in specialized care for abstinence and retention | |

| Lintzeris 2004 (19) | RCT N=139 | Primarily primary care (18 general practitioner practice sites and 1 office-based specialist clinic). Australia | A: Office-based buprenorphine (with pharmacy dispensing) (n=73) B: Methadone clinic-based buprenorphine (n=66) |

Heroin use, retention similar in both groups | Study focused on initiation of buprenorphine. Methadone patients had to be below 60 mgs before they tried to initiate buprenorphine |

| U.S.-based Observational Studies | |||||

| Fiellin 2004 (30) Qualitative analysis of Fiellin 2001 | Clinical chart audit of the 22 patients who received office-based methadone and focus group with 6 participating physicians providing care in the 2001 RCT of office-based methadone | To evaluate processes of care during office-based treatment of OUD with methadone | Lapses in care (urine drug monitoring, paperwork completion) and barriers (logistics of dispensing, receipt of urine toxicology results, difficulties arranging psychiatric services, communications with OTP, and non-adherence to medication) identified. Physicians recommended dispensing in pharmacies rather than their office. | Small sample no comparison group | |

| Drucker 2007 (20) Includes pharmacy dispensing | Observational study uncontrolled retrospective treatment series N=10 Used FDA IND from Harris 2006 | Office-based specialty setting Lancaster, PA, U.S. | To evaluate methadone agonist therapy in an office-based specialty setting with pharmacy dispensing in stabilized patients | 10 patients enrolled in office-based methadone and able to receive methadone in a community pharmacy. 1% (2/216) of urine drug tests positive for illicit substances; patients reported increased satisfaction | Small sample, no comparison group |

| Harris 2006 (21) Includes pharmacy dispensing | Observational study uncontrolled retrospective treatment series N=127 FDA IND | Office-based specialty setting NYC, U.S. | To report outcomes of office-based medical methadone program (n=127)and a comparison with OTP patients (n=3,342). Medical methadone patients were 1) employed (or unemployed due to disability or retirement); 2) no evidence of opioid, cocaine, or benzodiazepine abuse in last 3 years; 3) psychiatric stability. Methadone dispensed from a central pharmacy | Patients in office-based methadone medical were older than traditional OTP patients (52 vs. 44 years), more likely male (72% vs. 59%), and more likely Caucasian (50% vs. 17%). Proportion with urine sample positive for non-prescribed opiates 0.8% and for cocaine 0.4% | Small sample, in office-based group |

| Merrill 2005 (22) Includes pharmacy dispensing | Observational study uncontrolled retrospective treatment series N=30 SAMHSA and DEA exceptions | Primary care Seattle, WA, U.S. | To evaluate medical methadone therapy in primary care settings in stabilized patients. The hospital pharmacy dispensed the methadone | Retention at 1 year 93%, positive urine drug screen 6.7%, improvement in Addiction Severity Index over time and patient satisfaction high. | Small sample, no comparison group |

| Des Jarlais 1985 (23) Initial patients for Novick series | Observational study uncontrolled retrospective treatment series N=28 (first 28 patients) at 12-month follow-up FDA IND | Office-based specialty setting. NYC, U.S. Office-based (providers with experience in drug abuse treatment) | To evaluate methadone agonist therapy in an office-based specialty setting in stabilized patients | At 12 months, 89% (25/28) retention; 1 patient successfully detoxified, 1 required short-acting opioid for surgery and back pain, and 1 requested transfer back to methadone clinic. Patients reported more mobility and privacy, less anxiety about treatment, improved employment situation, and improved selfesteem, and perceived reduction in stigma. | Small sample, no comparison group |

| Novick 1988 (25) | Patients transferred from Rockefeller University to Beth Israel OTP N=40 (first 40 participants) | Same as above | Methadone was from the hospital pharmacy and dispensed in the primary care office | 12 to 55 months of follow-up. 83% remained on medical methadone with 94% annual retention rate. 5 returned to OTP because of cocaine use. | Same as above |

| Novick 1994 (24) | N=100 Follow-up data for 3.5 to 9.25 years (or status at discharge) | Same as above | Same as above | Retention 98%, 95%, and 85% at 1, 2, and 3 years. Cumulative proportional survival in treatment 0.74 at 5 years and 0.56 at 9 years. After 42 to 111 months, 72 patients remained in good standing, 15 patients had unfavorable discharge, 7 voluntarily withdrew in good standing, 4 died, 1 transferred to chronic care facility, and 1 voluntarily left program | Same as above |

| Salsitz 2000 (26) Report on 15 years | N=158 | Same as above | Same as above | 132 (84%) were program compliant and treatable within office-based settings. Retention at 1 year (99%), 2 years (96%), three years (89%). 13% died (no overdoses). 16% returned to OTP | Same as above |

| Schwartz et al, 1999 (27) | Observational study uncontrolled retrospective treatment series N=21 FDA IND | Primary care Baltimore, U.S. | To evaluate medical methadone therapy in primary care settings in stabilized patients Methadone was dispensed in the primary care office | After 12 years, 29% of patients dropped out, 0.5% urine samples positive for drugs; no methadone overdose or diversion; participants reported significant improvement in quality of life | Small sample, no comparison group |

| Non-U.S. Observational Studies | |||||

| Gossop 2003 (28) | Observational study Prospective sample N=240 | Primary care vs. drug clinic United Kingdom | A: Methadone in general practitioner clinics with dispensing from the office or community pharmacy (n=79) versus B: Methadone in drug clinics with dispensing in the clinic or community pharmacy (n=161) | Reductions in illicit drug use, injecting, sharing injection equipment, psychological and physical health problems, and crime decreased in both groups at 1 and 2 years. Patients in general practitioner settings had less frequent benzodiazepine and stimulant use, and fewer psychological health problems | |

| Mullen 2012 (29) | Retrospective randomly selected sample of methadone admissions in 1999, 2001 and 2003 N = 1,269 | Central methadone treatment list Ireland | Random sample of new patients receiving methadone treatment from specialty clinics, community medical clinics and trained physicians in 1999, 2001 and 2003 to assess variables associated with retention in care | Participants were primarily men (69%) with a mean age of 26 years (75% under 30 years of age). 95% received daily dosing with a mean dose of 58 mg/day. Doses in primary care were lower (53 mg/day) compared to specialty clinics (60 mg/day). 61% remained in care for more than 1 years. Primary cause of leaving in less than one year was “treatment failure”. Logistic regression suggested retention at 12 months was associated with gender (women were more likely to remain in care). Patients in specialty clinics were two times more likely to leave care than those in physician care. Patients with a daily dose less than 60 mg/day were 3 times more likely to leave care than patients with doses greater than 60 mgs. | |

| U.S. and non-U.S. Pharmacy Studies | |||||

| Bowden 1976 (31) | Descriptive, uncontrolled retrospective treatment series of OTP patients with pharmacy dispensing N=96 Began prior to FDA regulations | Community pharmacies San Antonio, TX, U.S. | To describe community pharmacy dispensing of methadone for OUD (n=96). Data collection began prior to the 1973 FDA regulations that restrict dispensing to OTPs | Retention 70% at 1 year, 3% voluntarily abstinent, 10% using heroin, 9% jail, prison, or hospital, 1% dead, 63% employed and 15% partially employed. Proportion arrested one or more times in the prior year decreased from 66% to 58% | Small sample, no comparison group |

| Joudrey 2020 (4) | Descriptive, cross sectional analysis of travel time to OTPs and pharmacies N=7,918 census tracts in five states | OTPs vs community pharmacies U.S | To compare drive time to OTP vs. community pharmacies | Median drive time longer to OTP than chain pharmacies (19.6 vs. 4.4 minutes); difference greater in increasingly rural census tracts (11.5 to 35.2 minutes) | |

| Kleinman, 2020 (5) | Descriptive, cross sectional analysis of travel time to OTPs and pharmacies N=72,443 census tracks in U.S. | OTPs vs community pharmacies U.S. | To compare drive time to OTPs (n = 1,682) vs community pharmacies (n = 69,475) | Mean population weighted driving time was 20.4 minutes to OTPs and 4.5 minutes to pharmacies. Drive times increased in metropolitan and noncore counties | |

| Keen 2002 (32) | Descriptive, ecological analysis of methadone deaths before and after pharmacy dispensing of methadone as an opioid agonist therapy N=400 | Primary care United Kingdom | To evaluate trends in methadone associated mortality in city following implementation of widespread methadone prescribing in primary care Dispensing in community pharmacy | Decrease in methadone deaths in city following implementation of widespread methadone prescribing in primary care, despite increase in methadone prescribing | |

Abbreviations: DEA = Drug Enforcement Administration, FDA = Food and Drug Administration, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IND = Investigational New Drug, NTP = narcotic treatment program, NYC = New York City, OTP = opioid treatment program; OUD = opioid use disorder; PWID = people who inject drugs; RCT = randomized controlled trial; U.S. = United States; vs = versus

U.S. clinical trials.

The first clinical trial of office-based methadone (“medical methadone maintenance”) was a 1993 initiative in Chicago that recruited 130 stable patients from 14 OTPs (15). The study selected patients with a year or more of methadone treatment and, for the past six-months, with a) no positive urine screens, b) employed, c) plans to remain on methadone for next year, and d) compliant with treatment plans. Participants were randomized on a 2 to 1 basis into medical methadone (n = 87) or continuing care at the OTP (n=43). Medical methadone patients received monthly physician visits and completed two medication visits per month at their original OTP and received 13 days of take-homes. The OTP continued to provide counseling services. The comparison group remained in their OTP with two medication visits per week (n = 43) (i.e., 2 or 3 take-homes per visit). After six months, participants in the comparison group were enrolled in the medical methadone program. The two groups had similar completion rates at six (89% vs 85%) and 12 months (both groups = 73%) and rates of positive urine screens were less than 1% in both groups (16). All patients were satisfied with the services and none wanted to return to treatment as usual (2 medication visits per week) (15).

The second trial, in New Haven Connecticut recruited 46 stable methadone patients (i.e., an OTP patient for more than one year, no positive urine screens for opioids or cocaine in past year, planned to remain in the OTP for six months, no co-occurring medical, psychiatric or substance use disorder, had transportation to the clinic or office, with legal income and stable housing) from an OTP and randomized participants to either six primary care internists who provided office-based methadone agonist therapy (n = 22) (with methadone dispensed in the physician’s office) or to usual care in the OTP (n = 24) for six months (12). The groups had similar rates of opioid positive urine screens (9% vs. 11%) and clinical instability (i.e., defined a priori as two consecutive urine drug screens with cocaine or opiates metabolites or did not include methadone) (18% vs. 21%) during the 6-month study period; the office-based patients were more likely to rate the care as excellent (73% vs. 13%) (12). A secondary qualitative analysis (included in Table 1 as an observational study) reviewed the office records and interviewed physicians to identify barriers to office-based methadone. Physicians reported that the urine drug monitoring and extra paperwork required for methadone dispensing were barriers to continued office-based care and recommended future studies use pharmacies for dispensing (30). Additional barriers were patient access to psychiatric services, communication with the OTP and patient non-adherence to medication (30).

A third trial, based in Baltimore, randomized 92 stable methadone patients (i.e., in the past year “an uninterrupted episode or methadone maintenance, no positive urines” for any drug, verified employment, no failed methadone recalls, plans to remain in care for duration of the study) to three groups: 1) 28-day methadone treatment in a physician office (office-based, n = 32), 2) 28-day methadone maintenance in an OTP (clinic-based, n = 33), or 3) regular methadone maintenance in an OTP with one or two visits per week for medication (routine care, n = 27) (13). All study participants received an adaptive treatment model that intensified services (additional counseling required) if urine screens were positive for illicit drugs or the weekly medication checks were incorrect (14). After 6 months of the 12-month study period, the three study groups had similar outcomes: 1% of urine screens detected illicit drug use, drug diversion was not observed and methadone misuse was limited, patients were satisfied or very satisfied (patients receiving 28-day supplies of methadone were more satisfied) and patients accepted the treatment intensification (14). At the 12-month follow-up, 77 participants were still in care. Few patients tested positive for illicit drug use or missed medication recalls (groups did not differ significantly) (13). Groups also did not differ in the use of treatment intensification (36% of patients), self-reported drug use was minimal, and all patients reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the services. Both of the 28-day medication groups (office-based and clinic based), however, were more satisfied than those in routine care and were more likely to report improved employment and socialization activities (13).

The fourth trial, a pilot study in New Mexico, tested office-based primary care and methadone medical management with dispensing from community pharmacies and a social worker provided counseling and case coordination. Women (n=26) enrolled in an OTP and stable were randomized to either continued care in the OTP (n=12) or office-based care (n=14) (17). A treatment manual specified roles and responsibilities for the five pharmacists, five medical practitioners (four physicians and one nurse practitioner) and one masters level social worker with experience treating drug use disorders. The pharmacies registered with the DEA and dispensed methadone as medication units for the OTPs. The social worker provided clinical coordination, at least monthly psychosocial services (in her office or at the participant’s home) and participated in weekly case conferences. The medical practitioners were listed as OTP staff and met with patients at least monthly for medical and medication management and urine drug screens (16, 17). Patients eligible for the study had a) at least six months of methadone treatment, b) six months of stable methadone dose, c) at least two take-home doses per week, and d) plans to remain on methadone for the 12-month study. The analysis was restricted to participants who completed the 12-month follow-up period (n=22): office-based care (n=13), OTP care (n=9). Two office-based care participants were returned to the OTP early in the study period for illicit drug use and mental health problems. Patients in office-based care were less likely to use illicit opioids (23% vs. 78%, chi-square = 6.2, p < 0.01) during the 1-year test (16, 17). A qualitative analysis of a satisfaction survey suggested that patients receiving community services were pleased with the services and were treated well (16). The small sample generated imprecise estimates.

Non-U.S. randomized trials.

There were two non-U.S. randomized trials. One was conducted in France and one in Australia. The French trial (n=221) compared methadone initiation in primary care versus specialty care; it found methadone initiation in primary care was feasible and acceptable to physicians and patients, with similar rates of abstinence and retention compared with specialty care induction (18). Office-based methadone is not typically available in France and this was the first evaluation of office-based care. An Australian randomized trial (n=139) recruited stable methadone patients and active heroin users and randomized participants to receive buprenorphine in a methadone clinic (n=66) versus buprenorphine in an office-based setting (with pharmacy dispensing) (n=73) (19). Self-reported heroin use and retention in care were similar in both settings (19).

U.S. Observational Studies.

Observational studies, conducted in the U.S., echoed results from the clinical trials; stable methadone patients responded to office-based methadone with high levels of retention in care and low rates of drug use (21–27). With one exception (21), the studies only described patients who received office-based methadone and did not include an OTP comparison. Across studies, patients receiving office-based methadone generally had monthly physician visits with observed dosing and urine tests. In most of the studies, patients received take-home medication directly from the physician (pharmacies delivered medication to the office setting the day prior to scheduled appointments).

Dr. Marie Nyswander used an investigational new drug (IND) approval from the Food and Drug Administration to open the first “medical methadone maintenance” program for stable methadone patients in New York City in 1983; the initial paper described one-year results for 28 patients (23). The study was restricted to patients who met 10 eligibility criteria: 1) five years of conventional methadone treatment, 2) three years of stable employment, 3) no criminal involvement for past three years, 4) no illicit drug use and no alcohol abuse for past three years, 5) reliable clinic attendance, 6) a need for continued maintenance, 7) no need for psychiatric medication, 8) no social ties to drug users, 9) clinical recommendations to participate, and 10) a willingness to participate in research interviews. Take-home medication was dispensed during the medical visits. Subsequent analyses expanded the size of the program and the duration of follow-up from 40 patients with 12 to 55 months of follow-up (25) to 100 patients with up to nine years of follow-up (24) and 15 years with 158 study participants (26). Treatment retention rates declined slightly overtime, rates of discharge for drug use were low, and, over 15 years, 16% of the medical methadone patients were returned to methadone clinics.

A second New York City study, also conducted with an IND, compared office-based methadone patients to patients treated in an OTP (21). Participating patients were employed with no evidence of illicit drug use in past three years and psychiatrically stable. When the medical maintenance patients (n = 127) were compared to OTP patients (n = 3,342); patients in the office-based setting were older (52 vs. 44 years), more likely to be men (72% vs. 59%) and white (59% vs. 17%). Within the medical methadone group, the rate of illicit use of opioids and cocaine was less than 1% in monthly urine drug tests and unannounced recalls found no evidence of diversion or inappropriate use. Patients received take-home medication in a central pharmacy near the physician’s office (21).

The other studies reported outcomes of office-based methadone patients without comparisons to OTP patients. A Baltimore analysis described 21 stable methadone patients enrolled in a medical maintenance program with take-home methadone dispensed in the physician’s office (27). Participating patients were employed with five years of not using illicit drugs, no evidence of alcohol use disorder, and no occurring psychiatric disorders. Urine drug tests were completed monthly. After 12 years, 71% of the patients remained in care with 0.5% urines positive for drug use and no methadone overdoses or diversion (27). Participants reported significant improvement in quality of life and ability to travel.

A small study in rural Pennsylvania described the use of a community physician and a community pharmacy to monitor and dispense methadone to stable patients (n = 10) (i.e., a median of three years in OTP care without evidence of current drug use) living 40 miles from the OTP (20). The first pharmacy dispensing occurred in July 2003 (despite objections from the state alcohol and drug authority). All patients were enrolled in a local internal medicine clinic; the clinic’s director was certified in addiction medicine and wrote monthly medication orders that could only be filled at the participating pharmacy. The pharmacy observed one dose and provided weekly or bi-weekly take-home medication. The primary care practice provided counseling and urine testing. Participating patients paid pharmacy charges out-of-pocket. Five of 216 (2.3%) urine tests were positive for drugs other than methadone (3 for prescribed medications and 2 for illicit drugs). Study participants felt comfortable in the pharmacy and liked being treated like a customer, they were pleased with the physician and his skills, and grateful for the program. Pharmacy staff reported the bottle return requirement was unnecessary and the lock box was stigmatizing.(20) Despite the results, the state alcohol and drug authority remained uncomfortable with the program and in July 2005 ordered the patients to return to the original OTP 40 miles away. Most switched to buprenorphine and remained in care with the internal medicine clinic (20).

Harborview Medical Center in Seattle partnered with Evergreen Treatment Services (an OTP) and requested SAMHSA and DEA exceptions and state exemptions from opioid treatment regulations (22). The OTP continued to provide counseling; the hospital provided pharmacy and medical clinic services. The OTP patients were screened for medical maintenance eligibility; among the 49 individuals who met study eligibility criteria (i.e., at least 4 take-homes each week, with reliable attendance, monthly urine screens negative for drug use, no evidence of alcohol use disorder, no legal issues or unpaid program fees, no psychiatric disorders), 30 agreed to participate (22). Participants picked up methadone medication once or twice per month from the hospital pharmacy and pharmacists assessed patient stability, primary care needs, collected a monthly urine screen, observed the patient take their regular dose, and dispensed take-home doses. Monitoring included random call-backs which required patients to return to the pharmacy within 24 hours to confirm pill counts. Physician visits were adjusted based on clinical needs. When they entered medical maintenance, the patients had a mean age of 45, most were men (70%), white (83%), employed (83%), with a mean of 12 years on methadone, 7 years of take-home privileges and a mean daily dose of 63 milligrams of methadone; 80% had Medicaid or other health insurance. In the first 12 months of program participation, less than 1% of urine tests were positive for illicit drugs, call-backs found no discrepancies and two patients were transferred back to the OTP. The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) medical scale improved, other ASI scale scores were low and stable and 87% of the patients were very satisfied with the medical maintenance program (22).

Non-U.S. observational analyses.

The search found two non-U.S. observational analyses: one was conducted in England (28) and one in Ireland (29). England’s National Treatment Outcome Research Study compared patients with methadone prescriptions from a general practitioner (n = 79) to patients enrolled in specialized drug clinics (n = 161) (28). At 12- and 24-months post treatment entry, patients in both groups reported reduced illicit drug use, injecting, syringe sharing, mental health symptoms, medical problems and crime (28). Finally, a random sample of patients in Ireland’s Central Methadone Treatment List who began care in 1999, 2001 and 2003 (n = 1,269) assessed retention in care and patient characteristics associated with retention in care (29). Sixty-one percent of patients remained in care for more than one year and patients in primary care were twice as likely as patients in specialty methadone clinics to be retained for the full year (29).

Pharmacy dispensing.

Four U.S. studies of office-based methadone (described in prior sections) [three observational studies (20–22) and one clinical trial (17)] used pharmacies as medication units to dispense methadone take-home medication. When compared to the studies with office dispensing, outcomes appeared to be similar. A small trial used community pharmacies (with special approvals from the Drug Enforcement Administration) (17). An observational study described how the hospital pharmacy conducted observed doses and dispensed take-home methadone before business hours (22). A second study used a central pharmacy near the physician offices (21). In the third analysis, a community pharmacy dispensed methadone for rural patients who initially enrolled in an OTP 40 miles from where they lived (20).

A 1970 initiative in San Antonio, Texas utilized pharmacy dispensing to expand the OTP’s caseload by 30% (31). Each pharmacy purchased, stored and dispensed its own supply of methadone (1970 to 1972) until the 1973 FDA regulations required the OTP to purchase, store and deliver methadone as needed (31). The analysis described a group of 96 patients who received 12 months of methadone dispensed in pharmacies. The study did not include a comparison group (31). An ecological, before-after study in the United Kingdom found a decrease in methadone deaths following implementation of office-based methadone with pharmacy dispensing, despite increased methadone prescribing (32).

Two analyses using census track data observed that the patient’s travel burden for daily dispensing could be reduced if pharmacies dispensed methadone for patients. The drive time to an OTP was greater than the drive time to a pharmacy (20 minutes versus 4 minutes); the difference increased in rural communities (4, 5).

Discussion

Studies on office-based methadone were consistent in finding that stable methadone patients responded to office-based care with elevated treatment retention rates and greater treatment satisfaction, employment, and engagement in family and social activities (12–14, 22, 27). The operationalization of “stable patient” varied but typically required participants to have a year or more of urine drug tests negative for illicit drugs, reliable clinic attendance, housed and employed. There was no evidence of methadone diversion although only three of the studies included recalls to assess appropriate use of take-home medication (13, 21, 22).

The initial U.S. studies required IND approvals from the Food and Drug Administration for an exemption from U.S. regulations limiting methadone treatment to OTPs. Subsequent studies, however, were conducted with DEA and SAMHSA exemption requests for office-based practices affiliated with an OTP (8). Pharmacies can also be approved as OTP medication units specifically to dispense methadone with a formal OTP affiliation. These mechanisms, however, have not been used widely to promote access to methadone, despite increases in opioid use disorder and opioid overdoses.

One influence on the limited routine use of office-based methadone may be the economics and financing of OTPs. Stable patients are more likely to be employed with more income and, consequently, pay higher fees when sliding fee scales are applied to the cost of patient care (33). In the current system of OTP care, there is no economic incentive for OTPs to transfer the patients to primary care practices. Traditionally, third party payers often required OTPs to provide in-person care in order to receive reimbursement. The recent introduction of relaxed restrictions on take-home medication and permission to use telemedicine because of the COVID-19 pandemic (34) have begun to alter the payment structures for OTPs and may create incentives to expand caseloads by transferring stable patient to OTP affiliated physicians (e.g., in a hub-and spoke model).

Limitations.

The U.S. randomized trials were unblinded, with small samples in most of the studies that may have been underpowered to detect differences in outcomes. Study samples were also too small to detect infrequent adverse events and follow-up periods varied across the studies. The observational studies were primarily descriptive and most did not control for possible confounding characteristics or include comparison groups. Few studies, moreover, have been conducted in the last 20 years; results, therefore, are dated and may not generalize to the current environment. Nonetheless, the studies provide evidence that stable methadone patients benefit from office-based care.

Patients, however, were carefully selected and, although the operationalization of “stable patient” varied, at least six months of OTP care was required along with no evidence of drug use. No U.S. studies tested office-based care with patients new to care. In the French study, however, methadone patients successfully initiated methadone and stabilized in office-based settings. Finally, while office-based methadone is relatively common in other countries, the international studies relied on retrospective analyses using historical data and the clinical trials tested facets of methadone services (i.e., switching to buprenorphine) that may be of limited applicability to U.S. settings.

Practice & Policy Implications.

The association between access to opioid agonist therapy and improved patient outcomes is well described in the literature. Our findings suggest that modifications to current methadone policies to allow for health services delivery changes (specifically, office-based prescribing of methadone for stabilized patients) could enhance access to care. Pharmacy dispensing of methadone would further facilitate access to effective treatment for OUD especially in rural communities. Pharmacies are an integral part of methadone treatment in Canada and Europe. U.S. pharmacies already dispense methadone when it is prescribed for pain and there are no obvious barriers to using pharmacies in the U.S., aside from current DEA regulations that prohibit physicians from prescribing methadone for OUD and pharmacists from filling methadone prescriptions for OUD. Recent analyses highlight the distance many patients in rural areas travel to access methadone services and advocate for the use of rural pharmacies as medication units (3, 5)

An expansion of methadone services, moreover, may begin to address persistent racial disparities in care, which are observed in the current design of the OAT system (35, 36). Black patients, for example, are less likely to have access to and receive office-based care with buprenorphine (37). Implementation of office-based methadone should include a critical assessment impact on access with intentional efforts to increase access to minoritized populations.

Some physicians, moreover, appear to be interested in caring for their patients using methadone for OUD. Interviews with 71 primary care and HIV providers in 11 New York City practices determined that most (85%) had provided medical care for methadone patients, 70% were comfortable managing medical care for drug users in the primary care setting and 66% were willing to prescribe methadone for OTP patients on their caseload if training and support were available. Half the respondents, however, were concerned that methadone patients often have multiple needs that could be difficult to address in their practice setting (38). It should be noted, however, that relatively few physicians have the DATA 2000 waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD and that, among those with the waiver, many do not use the waiver. There is widespread hesitancy to address OUD in clinical practice.

Future Research.

It is noteworthy that, aside from recent modeling studies of drive time to pharmacies versus OTPs and two international analyses, all of the papers were published in the 1980s,1990s and the first decade of the 21st Century. New trials of office-based methadone using contemporary patients with OUD would help verify the continued applicability of office-based methadone.

In addition, all of the U.S. studies were limited to stable OTP patients. As a result, the lack of data on patients new to care is a major gap in the research literature. There are no data on the risks and benefits of office-based methadone for patients new to care. While clinical evidence suggests that patients continue to use drugs while new to care, the evidence also suggests that, for many patients, opioid agonist therapy helps them stabilize; they respond well to care and drug use dissipates over time. It is likely that some Federally Qualified Health Centers have the resources and skills to work effectively with methadone patients who are new to care. Given the needs for more access to methadone services in nonmetropolitan communities, it is critical to test office-based methadone for patients seeking treatment for opioid use disorder; one option would be to extend the buprenorphine hub-and-spoke model to include methadone patients (patients are stabilized on medication in an OTP and transferred to office-based practices when stable (39–41).

Despite the potential advantages of methadone dispensing in pharmacies, prior research is limited. Our search found only five studies that used pharmacy dispensing and one study was initiated prior to the 1973 methadone regulations (31); in two studies, the pharmacies operated as medication units (17, 22). Qualitative implementation research would be useful to understand perceived barriers to the use of pharmacies to dispense methadone and development of strategies to address potential barriers. Clinical trials and other studies evaluating clinical or administrative data are needed to document the safety of pharmacy dispensing and potential effects on reducing burdens on patients, particularly for those located in areas requiring lengthy travel to an OTP. Additional research could inform changes to regulations to encourage greater use of pharmacies for methadone dispensing.

Another strategy to increase access to methadone is use of mobile medication units – methadone vans. Since 2006, the DEA has not approved new mobile medication units. Aside from a handful of studies (42, 43), little systematic research has been conducted testing facets of mobile medication units. In February 2020, the DEA released a draft of changes in DEA regulations that would permit a resumption of approvals. Renewed approvals will provide opportunities for implementation research on the development and use of mobile medication units.

Conclusion.

In stable patients, office-based methadone appears to be associated with similar retention, drug use, and other outcomes found in stable OTP patients and may enhance quality of life and satisfaction with care. Research is needed on office-based methadone for patients new to care. Office-based methadone and pharmacy dispensing, moreover, could enhance access to methadone treatment for patients with OUD. Because of the complexity of 42 CFR Part 8, a comprehensive review of OTP regulations may be useful, including an update of the 1995 Institute of Medicine review of methadone regulations (44).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

An award from Arnold Ventures (20-04132) supported the evidence review. Drs. McCarty and Hoffman received support through awards from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (UH3 DA044831, UG1 DA015815). Dr Priest received support though an award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F30 DA 044700).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Hoffman and McCarty served as investigators on NIH supported trials using donated medications from Alkermes and Indivior. Drs. Hoffman and McCarty report no additional financial relationships with commercial interests. Drs Chan, Chou, Priest and Ms. Bougatsos and Ms. Grusing report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Title 42, Part 8 2016. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=3&SID=7282616ac574225f795d5849935efc45&ty=HTML&h=L&n=pt42.1.8&r=PART. [PubMed]

- 2.Jackson JR, Harle CA, Silverman RD, Simon K, Menachemi N. Characterizing variability in state-level regulations governing opioid treatment programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;115:108008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joudrey PJ, Edelman EJ, Wang EA. Drive times to opioid treatment programs in urban and rural counties in 5 US States. Jama. 2019;322(13):1310–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joudrey PJ, Chadi N, Roy P, Morford KL, Bach P, Kimmel S, et al. Pharmacy-based methadone dispensing and drive time to methadone treatment in five states within the United States: a cross-sectional study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;211:107968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinman RA. Comparison of driving times to opioid treatment programs and pharmacies in the US. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samet JH, Botticelli M, Bharel M. Methadone in primary care - one small step for congress, one giant leap for addiction treatment. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin H, Marshall BDL, Degenhardt L, Strang J, Hickman M, Fiellin DA, et al. Global opioid agonist treatment: a review of clinical practices by country. Addiction. 2020;14:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Dear colleague letter on methadone medical maintenance Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2000. [Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/medication_assisted/dear_colleague_letters/2000-colleague-letter-methadone-medical-maintenance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sucharew H, Macaluso M. Progress notes: methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):416–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarty D, Chan B, Hoffman K, Priest KC, Bougatsos C, Grusing S, et al. Methadone Treatment Regulations in the United States: History, Current Status, Evidence, and Policy Considerations Portland, OR: Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, Oregon Health & Science University; 2020September2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiellin DA, O’Connell PG, Chawarski M, Pakes JP, Pantalon MV, Schottenfeld RS. Methadone maintenance in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2001;286(14):1724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King VL, Kidorf MS, Stoller KB, Schwartz R, Kolodner K, Brooner RK. A 12-month controlled trial of methadone medical maintenance integrated into an adaptive treatment model. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(4):385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King VL, Stoller KB, Hayes M, Umbricht A, Currens M, Kidorf MS, et al. A multicenter randomized evaluation of methadone medical maintenance. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;65(2):137–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senay EC, Barthwell AG, Marks R, Bokos P, Gillman D, White R. Medical maintenance: a pilot study. J Addict Dis. 1993;12(4):59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuchman E A model-guided process evaluation: office-based prescribing and pharmacy dispensing of methadone. Eval Program Plann. 2008;31(4):376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuchman E, Gregory C, Simson M, Drucker E. Safety, efficacy, and feasibility of office-based prescribing and community pharmacy dispensing of methadone: results of a pilot study in New Mexico. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2006;5(2):43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrieri PM, Michel L, Lions C, Cohen J, Vray M, Mora M, et al. Methadone induction in primary care for opioid dependence: a pragmatic randomized trial (ANRS Methaville). PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lintzeris N, Ritter A, Panjari M, Clark N, Kutin J, Bammer G. Implementing buprenorphine treatment in community settings in Australia: experiences from the Buprenorphine Implementation Trial. Am J Addict. 2004;13Suppl 1:S29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drucker E, Rice S, Ganse G, Kegley JJ, Bonuck K, Tuchman E. The Lancaster office based opiate treatment program: a case study and prototype for community physicians and pharmacists providing methadone maintenance treatment in the United States. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2007;6(3):121–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris KA Jr., Arnsten JH, Joseph H, Hecht J, Marion I, Juliana P, et al. A 5-year evaluation of a methadone medical maintenance program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(4):433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrill JO, Jackson TR, Schulman BA, Saxon AJ, Awan A, Kapitan S, et al. Methadone medical maintenance in primary care. An implementation evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):344–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Des Jarlais DC, Joseph H, Dole VP, Nyswander ME. Medical maintenance feasibility study. NIDA Res Monogr. 1985;58:101–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novick DM, Joseph H, Salsitz EA, Kalin MF, Keefe JB, Miller EL, et al. Outcomes of treatment of socially rehabilitated methadone maintenance patients in physicians’ offices (medical maintenance): follow-up at three and a half to nine and a fourth years. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(3):127–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick DM, Pascarelli EF, Joseph H, Salsitz EA, Richman BL, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Methadone maintenance patients in general medical practice. A preliminary report. Jama. 1988;259(22):3299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salsitz EA, Joseph H, Frank B, Perez J, Richman BL, Salomon N, et al. Methadone medical maintenance (MMM): treating chronic opioid dependence in private medical practice--a summary report (1983–1998). Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(5–6):388–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz RP, Brooner RK, Montoya ID, Currens M, Hayes M. A 12-year follow-up of a methadone medical maintenance program. Am J Addict. 1999;8(4):293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gossop M, Stewart D, Browne N, Marsden J. Methadone treatment for opiate dependent patients in general practice and specialist clinic settings: outcomes at 2-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(4):313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullen L, Barry J, Long J, Keenan E, Mulholland D, Grogan L, et al. A national study of the retention of Irish opiate users in methadone substitution treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(6):551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Processes of care during a randomized trial of office-based treatment of opioid dependence in primary care. Am J Addict. 2004;13Suppl 1:S67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowden CL, Maddux JF, Esquivel M. Methadone dispensing by community pharmacies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1976;3(2):243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keen J, Oliver P, Mathers N. Methadone maintenance treatment can be provided in a primary care setting without increasing methadone-related mortality: the Sheffield experience 1997–2000. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(478):387–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz RP, Tommasello AC. Medical maintenance in methadone care: A clinical pharmacy practice opportunity. J Pharm Pract. 1997;10(5):346–51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIlveen JW, Hoffman K, Priest KC, Choi D, Korthuis PT, McCarty D. Reduction in Oregon’s methadone dosing visits following the SARS-CoV-2 restrictions on take-home medication. J Addict Med. 2021;online in advance of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen HB SKR Two tiers of biomedicalization: Methadone, buprenorphine and the racial politics of addiction treatment. Advances in Medical Sociology. 2012;14(12):79–102. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(3):367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagisetty P, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNeely J, Drucker E, Hartel D, Tuchman E. Office-based methadone prescribing: acceptance by inner-city practitioners in New York. J Urban Health. 2000;77(1):96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rawson R, Cousins SJ, McCann M, Pearce R, Van Donsel A. Assessment of medication for opioid use disorder as delivered within the Vermont hub and spoke system. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;97:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miele GM, Caton L, Freese TE, McGovern M, Darfler K, Antonini VP, et al. Implementation of the hub and spoke model for opioid use disorders in California: Rationale, design and anticipated impact. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;108:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawasaki S, Francis E, Mills S, Buchberger G, Hogentogler R, Kraschnewski J. Multi-model implementation of evidence-based care in the treatment of opioid use disorder in Pennsylvania. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;106:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenfield L, Brady JV, Besteman KJ, De Smet A. Patient retention in mobile and fixed-site methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42(2):125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall G, Neighbors CJ, Iheoma J, Dauber S, Adams M, Culleton R, et al. Mobile opioid agonist treatment and public funding expands treatment for disenfranchised opioid-dependent individuals. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(4):511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rettig RA, Yarmolinsky A, editors. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.