Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Cannabis use among older adults is increasing sharply in the United States (U.S.). While the risks and benefits of cannabis use remain unclear, it is important to monitor risk factors for use, including low perception of harm. The objective of this study was to estimate recent national trends in perceived risk of cannabis use among older adults.

Design:

Trend analysis.

Setting/Participants:

A total of 18,794 adults age ≥65 years participating in the 2015–2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a cross-sectional nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized individuals in the U.S.

Measurements:

We estimated the prevalence of older adults who believe that people who smoke cannabis once or twice a week are at great risk of harming themselves physically and in other ways. This was examined across cohort years and stratified by demographic characteristics, diagnosis of chronic disease, past-month tobacco and binge alcohol use, and all-cause emergency department use.

Results:

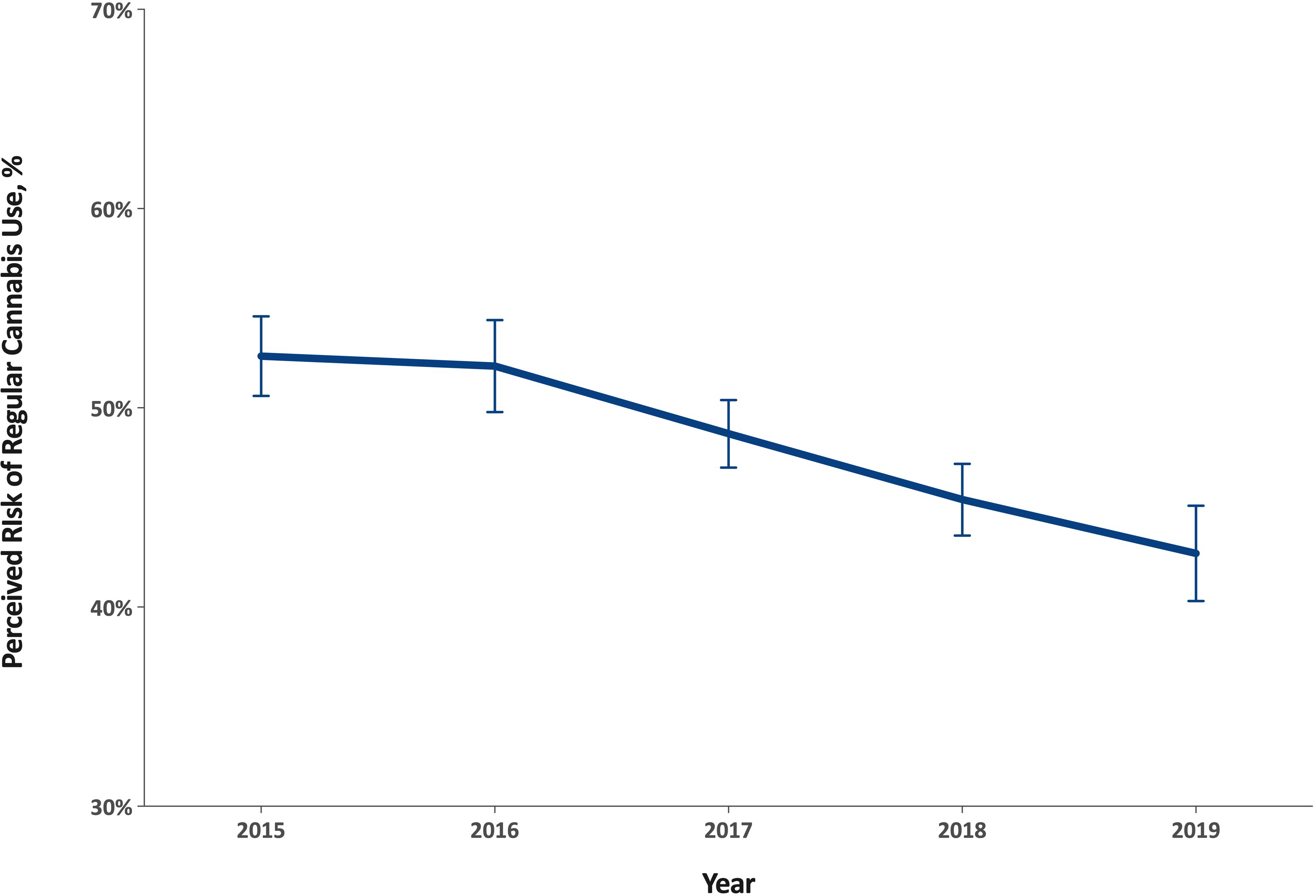

Between 2015 and 2019, perceived risk associated with regular use decreased from 52.6% to 42.7%, an 18.8% decrease (p<0.001). Decreases in perceived risk were detected in particular among those never married (a 32.6% decrease), those who binge drink (a 31.3% decrease), use tobacco (a 26.8% decrease), have kidney disease (a 32.1% decrease), asthma (a 31.7% decrease), heart disease (a 16.5% decrease), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (a 21.5% decrease), two or more chronic conditions (a 20.2% decrease), and among those reporting past-year emergency department use (a 21.0% decrease) (ps<0.05).

Conclusions:

The perceived risk of regular cannabis use is decreasing among older adults. We detected sharp decreases in risk perception among those with chronic disease and high-risk behaviors, including tobacco and binge alcohol use. As the number of older adults who use cannabis increases, efforts are needed to raise awareness of the possible adverse effects with special emphasis on vulnerable groups.

Keywords: Cannabis, marijuana, risk perception, geriatrics

Introduction

Past-year cannabis use by older adults in the United States (U.S.) increased sharply over the previous decade from an estimated prevalence of 0.7% in 2009 to 4.2% in 2018.1–2 This coincided with the increase in states legalizing its use for medicinal and recreational purposes.3–4 While there is some evidence that cannabis helps treat a range of symptoms, including peripheral neuropathy, nausea, and spasticity,5–8 the evidence-base for benefit is limited.5–8 Recent studies of older patients in primary care clinics in states with legalized medical and recreational cannabis found that most older adults used it for pain, arthritis, sleep, and anxiety,9–10 indications for which the evidence remains limited. Also, older adults are often more vulnerable to the potential harms associated with psychoactive substance use due to the presence of underlying chronic conditions, physiological changes of aging, and concurrent medication use.

An individual’s perception of risk is an important determinant of whether a person will engage in certain health-related behaviors.11 With the changing legal landscape of cannabis throughout the country, the use and perceptions of its use are changing. For example, perceived availability and increase in past-month cannabis use was found among states with medical marijuana laws.3 With increasing use there is a decrease in perceptions of harm.12 A study examining national data from 2002 to 2012 found that adults age ≥50 consistently had the highest prevalence and increased odds of perceived risk associated with cannabis, but prevalence decreased during the study period.13 While the clinical benefits of cannabis are being determined, like other medications—especially those with psychoactive properties, regular cannabis use may pose harm for older adults with certain chronic conditions.14–15 Therefore, as cannabis use among older adults continues to increase, the purpose of this study was to examine recent national trends in the perception of the risk of cannabis use among adults age ≥65.

Methods

Study Sample

The study sample comes from a repeated cross-sectional sample of participants age ≥65 from the most recent five years (2015–2019) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (n=18,794). NSDUH is an annual cross-sectional nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized individuals in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.16 A nationally representative probability sample of individuals is obtained each year through four stages and surveys are interviewer-administered via computer-assisted interviewing and audio computer assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). The weighted interview response rates were 64.9–69.3% between 2015 and 2019.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to provide data regarding their sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Asian, or Other), income (<$20,000, $20,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, or ≥75,000), and marital status (married, widowed, divorced or separated, or never married). They were asked if a doctor had ever informed them that they have a heart condition, diabetes, bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney disease, asthma, hypertension, and cancer. We also coded a variable indicating the diagnosis of two or more chronic conditions.17 Participants were also asked about cannabis use, tobacco use, and binge drinking of alcohol. Binge drinking was defined as consuming five or more alcoholic beverages on the same occasion for men and four or more for women. Participants were also asked about all-cause emergency department (E.D.) use in the past year and this variable was chosen as a sub-group because this population may be at risk for harms from cannabis use. NSDUH provided a variable indicating whether the participant resided in a state where medical cannabis was legal during the time of the interview.

Perceived Risk of Cannabis Use

NSDUH asks participants whether they perceive risk associated with using cannabis on a regular basis by answering the question: “How much do people risk harming themselves physically and in other ways when they smoke (cannabis) once or twice a week?” Response options were as follows: ‘no risk’, ‘slight risk’, ‘moderate risk’, and ‘great risk’. We dichotomized perceived risk for this analysis as “great risk” versus “other perceived risk” based on previous research.18–20 Due to changes in survey redesign in 2015,21 we limited analyses to 2015–2019.

Data analysis

We estimated prevalence of perceived “great risk” across cohorts and stratified by each level of demographics, substance use, chronic disease, and E.D. use. We calculated the absolute and relative change in prevalence of perceived great risk between the years 2015 and 2019. Absolute change was calculated as the difference between 2015 and 2019 prevalence, and relative change was calculated as the relative size in the absolute change in 2019 prevalence compared to 2015.2 Log-linear associations between perceived risk and year were estimated separately for each strata using logistic regression as this allowed us to estimate odds of risk as a linear function of time as a continuous predictor as done in previous studies.2 All analyses used sample weights provided by NSDUH to address complex survey design, non-response, selection probability, and population distribution. Stata S.E. 13 was used to analyze all data and Taylor series estimation methods were used to provide accurate standard errors.22 Imputed variables from NSDUH were chosen to limit missing data. This secondary data analysis was exempt from review from New York University’s institutional review board.

Results

Table 1 presents the estimated prevalence of respondents reporting that there is a great risk associated with weekly cannabis use stratified by participant characteristics. We estimate that in 2015, 52.6% of adults ages 65 and older in the U.S. perceived great risk of using cannabis weekly, and in 2019 this estimate dropped to 47.2%, an 18.8% relative decrease (p<0.001) (Figure 1). Among demographic sub-groups, the largest reductions in perceived risk were found among those never married (43.9% to 29.6%, a 32.6% relative decrease, p=0.02), among men (46.2% to 36.0%, a 22.1% relative decrease, p<0.001), and among those living in states where medical cannabis was legal at the time of interview (49.2% to 39.8%, a 19.1% relative decrease, p<0.001).

Table 1:

Trends in perceived risk of regular cannabis use by socio-demographics, chronic disease, and substance use characteristics for adults 65 years and older, United States 2015–2019

| Weighted % | % Change From 2015 to 2019 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | % absolute change | % relative change | Linear trend p-value | |

| Perceived risk of regular cannabis use | 52.6 | 52.1 | 48.7 | 45.4 | 42.7 | −9.9 | −18.8 | <0.001 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||||

| No past-year use | 53.9 | 53.8 | 50.5 | 47.2 | 44.8 | −9.1 | −16.9 | <0.001 |

| No past-month use | 53.3 | 53.3 | 49.9 | 46.6 | 44.1 | −9.2 | −17.3 | <0.001 |

| Legal in state | 49.2 | 45.6 | 44.1 | 42.5 | 39.8 | −9.4 | −19.1 | <0.001 |

| Not legal in state | 55.6 | 58.9 | 56.7 | 51.1 | 49.2 | −6.4 | −11.5 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 46.2 | 45.5 | 41.7 | 39.6 | 36.0 | −10.2 | −22.1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 57.9 | 57.5 | 54.3 | 50.1 | 48.1 | −9.8 | −16.9 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 49.4 | 49.4 | 45.6 | 44.1 | 40.1 | −9.3 | −18.8 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 60.2 | 55.9 | 53.7 | 46.3 | 47.2 | −13.0 | −21.6 | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 72.8 | 73.4 | 64.9 | 61.9 | 56.8 | −16.0 | −22.0 | 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 59.6 | 64.9 | 67.8 | 42.6 | 51.5 | −8.1 | −13.6 | 0.05 |

| Other | 53.1 | 41.1 | 40.6 | 29.6 | 38.4 | −14.7 | −27.7 | 0.06 |

| Total family income | ||||||||

| <$20,000 | 61.1 | 62.6 | 58.2 | 49.5 | 49.4 | −11.7 | −19.1 | <0.001 |

| $20-$49,999 | 57.5 | 57.2 | 53.2 | 50.7 | 45.4 | −12.1 | −21.0 | <0.001 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 47.3 | 47.0 | 45.8 | 42.9 | 43.5 | −3.8 | −8.0 | 0.16 |

| ≥$75,000 | 44.0 | 42.4 | 39.7 | 38.6 | 36.1 | −7.9 | −18.0 | 0.004 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 52.0 | 52.7 | 47.6 | 45.5 | 43.1 | −8.9 | −17.1 | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 60.2 | 56.7 | 59.8 | 51.9 | 50.3 | −9.9 | −16.4 | 0.003 |

| Divorced or separated | 45.6 | 46.7 | 41.1 | 40.7 | 34.3 | −11.3 | −24.8 | 0.001 |

| Never married | 43.9 | 40.0 | 41.7 | 31.6 | 29.6 | −14.3 | −32.6 | 0.02 |

| Chronic Disease | ||||||||

| Heart condition | 53.3 | 53.5 | 49.5 | 43.5 | 44.5 | −8.8 | −16.5 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 55.0 | 54.6 | 50.5 | 50.7 | 44.1 | −10.9 | −19.8 | 0.001 |

| Bronchitis/COPD | 50.3 | 48.7 | 50.6 | 44.2 | 39.5 | −10.8 | −21.5 | 0.02 |

| Kidney disease | 58.6 | 50.5 | 50.8 | 44.5 | 39.8 | −18.8 | −32.1 | 0.001 |

| Asthma | 50.8 | 49.0 | 49.6 | 40.1 | 34.7 | −16.1 | −31.7 | <0.001 |

| HTN | 53.3 | 48.9 | 48.8 | 45.6 | 43.9 | −9.4 | −17.6 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 49.5 | 51.0 | 47.2 | 43.9 | 38.0 | −11.5 | −23.2 | 0.001 |

| ≥2 of the above chronic conditions | 51.6 | 50.9 | 47.5 | 44.8 | 41.2 | −10.4 | −20.2 | <0.001 |

| Substance use (past-month) | ||||||||

| Tobacco use | 36.6 | 40.1 | 36.9 | 30.4 | 26.8 | −9.8 | −26.8 | 0.001 |

| Binge drinking | 33.2 | 30.5 | 33.8 | 29.2 | 22.8 | −10.4 | −31.3 | 0.004 |

| Health care utilization | ||||||||

| All-cause emergency department use | 54.7 | 56.1 | 47.2 | 49.0 | 43.2 | −11.5 | −21.0 | <0.001 |

Figure 1: Trend in Prevalence of Perceived Risk of Regular Cannabis Use Among Adults 65 Year and Older in the United States, 2015 to 2019.

Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

There were also significant decreases in perceived risk among those with certain chronic medical conditions, including people with a heart condition, diabetes, and hypertension. Particularly notable decreases in perceived risk were detected among people with kidney disease (58.6% to 39.8%, a 32.1% relative decrease, p=0.001), COPD (50.3% to 39.5%, a 21.5% relative decrease, p=0.02), and those with two or more chronic conditions (51.6% to 41.2%, a 20.2% relative decrease, p<0.001). Also, there were significantly sharp decreases in perceived risk among those who used tobacco in the past month (36.6% to 26.8%, a 26.8% relative decrease, p=0.001) and binge drank in the past month (33.2% to 22.8%, a 31.3% relative decrease p=0.004).

Discussion

The present study estimated a decline in perceived risk of cannabis use over time across older adults in a nationally representative sample. The increase in interest for cannabis use as a therapeutic drug for a variety of health conditions and its decrease in stigma likely helps explain the drop in perceived risk among older adults.18 Our results are consistent with other studies that found that perceived risk associated with cannabis use is decreasing among middle-aged and older adults, although to a lesser extent compared to younger adults.13 We also found a larger decrease in risk perception in states where cannabis is legal compared to states where it is not, however most studies that examine the use and perceptions of cannabis by older adults are in states that legalized cannabis.9–10 Longitudinal studies in more states with varying cannabis laws are needed to understand the changing perceptions of cannabis among older adults. While older adults may benefit from cannabis use for chronic symptoms such as pain,5,23 the decrease in perceived risk in our study was particularly pronounced among people who may be at particularly high risk for harm from cannabis use.

Older adults have a number of factors that place them at high risk for experiencing the harms associated with use of psychoactive substances compared to younger adults, including biological and psychosocial factors.24 In a study conducted by Hendrickson et al., older adults who used cannabis were also more likely to experience sedation and had higher rates of being unable to stand or having weakness than younger adults.25 This could place older adults using cannabis at higher risk for falls or injury. In addition, while the prevalence of cannabis use disorder (characterized by meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for substance use disorder) among older adults is low compared to younger adults, it does remain a risk for all people who use cannabis.26 Understanding these vulnerabilities is important for the safety of older adults as it can influence how healthcare providers discuss the potential benefits and harms of cannabis use.24

This study found a decrease in perceived risk among older adults with unhealthy substance use behaviors. Nationally there have been sharp increases in cannabis use among adults age ≥65 who also use alcohol and/or tobacco.1,2 The lower perceived risk of cannabis among people who binge drink or use tobacco has serious implications if this leads to increases in co-use of cannabis with other substances. Individuals who co-use alcohol and cannabis are at a higher risk of impairment and complications than those who use either alone.27 Additionally, the co-use of tobacco and cannabis is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes.28 Therefore, healthcare providers should inform older patients of the risks of co-use of cannabis with other substances to prevent harms.

Among the older adults with chronic diseases, we found the largest decrease in perceived risk for cannabis use among those reporting kidney disease. Cannabis may have benefit for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease or end stage renal disease (ESRD) given the high prevalence of pain, nausea, and anorexia among this population,29 similar to patients with cancer.5 Furthermore, the risk perception among older patients with ESRD or malignancy, may decrease given changing priorities in the setting of advanced disease. However, cannabis could pose potential harms for older adults living with existing chronic conditions. We estimated a 21.5% decrease in perceived risk associated with cannabis use among older adults with COPD. Smoked cannabis may have respiratory irritants and carcinogens that can lead to respiratory symptoms and inflammation and worsen outcomes for people living with this condition.11 The effect of cannabis on the cardiovascular system remains unclear, but there may be several mechanisms that may increase risk for cardiovascular outcomes.12 Furthermore, the psychoactive properties of cannabis could complicate the daily management of multiple chronic conditions among older adults or those with mental illness.

There are limitations to this study, including self-report, which may cause bias. However, the NSDUH does utilize ACASI in order to address responses to sensitive information. In addition, NSDUH only samples non-institutionalized people and would not capture older adults living in long-term care settings. NSDUH does not differentiate between perceived risk for cannabis use for recreational purposes versus medical. This is particularly relevant for this population as a study found that the majority of older adults found medical cannabis use acceptable, but only a third agreed on its acceptability for recreational purposes.30 Future studies on perception of risk should compare these two types of use. The perceived risk question asked about risk associated with smoking cannabis, so respondents may feel other methods of use are more or less risky. It is also unknown whether respondents interpreted the risk question about people in general or about people within their age group. Additionally, NSDUH does not ask about chronic pain or arthritis, common reasons for cannabis use among older adults.10 Finally, NSDUH is cross-sectional and cannot draw causal inferences as it relates to changes in perceived risk over time.

The benefits and risks of cannabis use remain unclear in the absence of large, randomized-controlled clinical trials that we expect from other therapeutics for practicing evidence-based medicine. While older adults may stand to benefit greatly from the use of cannabis, they are also vulnerable to potential harms from its use. Healthcare providers must convey possible risks of its use in light of unclear benefits especially to older adults at high risk for harms including people who engage in unhealthy alcohol use, tobacco use, or have certain chronic conditions.

Key points:

Among older adults, perceptions of the risks of regular cannabis use are decreasing.

Perceptions of risk are decreasing sharply among older adults who may be at risk for harms from cannabis.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

Decreases in perceptions of risks may lead to increases in cannabis use among high-risk older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Palamar has consulted for Alkermes otherwise the authors have no other potential conflicts to declare. Author Contributions: Han: conception and design; drafting the article; interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; final approval. Funk-White: drafting the article; analysis and interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; final approval. Ko: Literature review, revising the article critically for important intellectual content; final approval. Al-Rousan: analysis and interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; final approval. Palamar: conception and design; data analysis; interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; final approval. Sponsor’s Role: Authors receive grant funding from NIH/NIDA (PI Palamar: R01DA044207, PI Han: K23DA043651). The funding agency had no role in the study design, methods, interpretation of findings, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosures:

Sponsor’s Role: Authors receive grant funding from the NIH including NIDA (PI Palamar: R01DA044207, PI Han: K23DA043651) and NHLBI (PI: Al-Rousan: K23HL148530). The funding agency had no role in the study design, methods, interpretation of findings, or preparation of the manuscript. Findings from this paper will be presented as an abstract at the American Geriatrics Society National Meeting 2021.

References

- 1.Han BH, Sherman S, Mauro PM, Martins SS, Rotenberg J, Palamar JJ. Demographic trends among older cannabis users in the United States, 2006–13. Addiction. 2017;112(3):516–525. doi: 10.1111/add.13670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han BH, Palamar JJ. Trends in Cannabis Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2015–2018. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(4):609–611. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins SS, Mauro CM, Santaella-Tenorio J, et al. State-level medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived availability of marijuana among the general U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;169:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams AR, Santaella-Tenorio J, Mauro CM, Levin FR, Martins SS. Loose regulation of medical marijuana programs associated with higher rates of adult marijuana use but not cannabis use disorder. Addiction. 2017;112(11):1985–1991. doi: 10.1111/add.13904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briscoe J, Casarett D. Medical Marijuana Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(5):859–863. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minerbi A, Hauser W, Fitzcharles MA. Medical cannabis for older patients. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(1):39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt M, Stevens A, Thuku M, et al. Benefits and harms of medical cannabis: a scoping review of systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2019;8(1):320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds IR, Fixen DR, Parnes BL, et al. Characteristics and Patterns of Marijuana Use in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(11):2167–2171. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang KH, Kaufmann CN, Nafsu R, et al. Cannabis: An Emerging Treatment for Common Symptoms in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(1):91–97. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Conway KP, Colliver JD. Developments in the epidemiology of drug use and drug use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1494–1502. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pacek LR, Mauro PM, Martins SS. Perceived risk of regular cannabis use in the United States from 2002 to 2012: differences by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;149:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gates P, Jaffe A, Copeland J. Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: consideration of the literature. Respirology. 2014;19(5):655–662. doi: 10.1111/resp.12298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravi D, Ghasemiesfe M, Korenstein D, Cascino T, Keyhani S. Associations Between Marijuana Use and Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2018;168(3):187–194. doi: 10.7326/M17-1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2019 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). SAMHSA; September2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions—A Strategic Framework: Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Washington, DC. December2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipari RN, Ahrnsbrak RD, Pemberton MR, Porter JD. Risk and Protective Factors and Estimates of Substance Use Initiation: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In: CBHSQ Data Review. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); September2017.1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacek LR, Weinberger AH, Zhu J, Goodwin RD. Rapid increase in the prevalence of cannabis use among people with depression in the United States, 2005–17: the role of differentially changing risk perceptions. Addiction. 2020;115(5):935–943. doi: 10.1111/add.14883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palamar JJ, Le A, Mateu-Gelabert P. Perceived Risk of Heroin in Relation to Other Drug Use in a Representative US Sample. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2019;51(5):463–472. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2019.1632506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of the Effects of the 2015 NSDUH Questionnaire Redesign: Implications for Data Users. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); June2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA, 2010. Applied Survey Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning L, Bouchard L. Medical Cannabis Use: Exploring the Perceptions and Experiences of Older Adults with Chronic Conditions. Clin Gerontol 2021;44(1):32–41. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2020.1853299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuerbis A. Substance Use among Older Adults: An Update on Prevalence, Etiology, Assessment, and Intervention. GER. 2020;66(3):249–258. doi: 10.1159/000504363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrickson RG, McKeown NJ, Kusin SG, Lopez AM. Acute cannabis toxicity in older adults. Toxicology Communications. 2020;4(1):67–70. doi: 10.1080/24734306.2020.1852821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subbaraman MS, Kerr WC. Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the national alcohol survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39 (5):872–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters EN, Budney AJ, Caroll KM. Clinical correlates of co‐occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1404–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rein JL. The nephrologist’s guide to cannabis and cannabinoids. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020;29(2):248–257. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arora K, Qualls SH, Bobitt J, et al. Measuring Attitudes Toward Medical and Recreational Cannabis Among Older Adults in Colorado. The Gerontologist 2020;60(4):e232–e241. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]