Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Older adults’ susceptibility to mistreatment may be affected by their participation in social activities, but little is known about relationships between social participation and elder mistreatment.

Design:

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting/Participants:

National probability sample of older community-dwelling U.S. adults interviewed in 2015-2016, including 1,268 women and 973 men (mean age 75 years and 76 years, respectively; 82% non-Hispanic white).

Measurements:

Frequency of participation in formal activities (organized meetings, religious services, and volunteering) and informal social activities (visiting friends and family) was assessed by questionnaire. Elder mistreatment included emotional (4 items), physical (2 items), and financial mistreatment (2 items) since age 60. Multivariable logistic regression examined associations between each type of social participation and elder mistreatment among men and women, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, education, and comorbidity.

Results:

Forty percent of women and 22% of men reported at least one form of mistreatment (emotional, physical, or financial). Women reporting at least monthly engagement in formal social activities were more likely to report emotional mistreatment (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09-2.33). Among men, monthly organized meeting attendance was associated with increased odds of emotional mistreatment (AOR 1.34, 95% CI 1.01-1.93). Weekly informal socializing was inversely associated with emotional mistreatment (AOR 0.59, 95% CI 0.44-0.78) and financial mistreatment (AOR 0.59, 95% CI 0.42-0.85) among women.

Conclusion:

In this national cohort, older adults who were frequently engaged in formal social activities reported similar or higher levels of mistreatment compared to those with less frequent organized social participation. Older women with regular informal contact with family or friends were less likely to report some kinds of mistreatment. Strategies for detecting and mitigating elder mistreatment should consider differences in patterns of formal and informal social participation and their potential contribution to mistreatment risk.

Keywords: Elder mistreatment, social participation, elder abuse, NSHAP

Introduction

Recent global events have amplified social disconnectedness and raised concerns about the potential impact of disconnectedness on health. Previous studies have shown that older adults with less frequent social engagement can become socially isolated, with potentially damaging effects on their physical and mental health.1, 2 However, little is known about how participation in social activities may influence older adults’ risk of harmful interpersonal experiences such as abuse or mistreatment, which may have even greater implications for health, functioning, and mortality in older age.3–9

The social context of older adults is a central domain for identifying and mitigating elder mistreatment, according to the Abuse Intervention Model proposed by Mosqueda and colleagues.10 Prior research has linked elder mistreatment to having fewer kin in core social networks, although its relationship with social participation beyond contact with immediate social network members is not well understood.11–13 Older adults who lack opportunities for wider social engagement in the community may be more vulnerable to mistreatment by the small set of individuals upon whom they depend. Less socially engaged adults may also have fewer opportunities to speak out about mistreatment, resulting in fewer opportunities for detection and intervention. In turn, mistreatment by partners or family members may cause older adults to withdraw from their social activities, resulting in a mutually reinforcing cycle of social disengagement and interpersonal abuse.

We sought to advance understanding of the relationship between social participation and elder mistreatment to provide insight into strategies for prevention and intervention. To that end, we analyzed data from a nationally-representative cohort of community-dwelling older adults including measures of social participation and elder mistreatment. We examined both formal social participation, such as attendance at religious services and organized meetings or volunteering, and informal socializing with family and friends. Given prior studies showing that older women generally report more frequent social participation and higher rates of mistreatment than men,6, 14, 15 we examined associations separately among older men and women. We hypothesized that more frequent social participation would be associated with a lower prevalence of emotional, physical, and financial mistreatment.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2015-2016 data collection round of the National Social Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) cohort. Details of the construction of this cohort have been described previously.11, 16 Briefly, the original NSHAP study involved multistage probability sampling of U.S. adults aged 57 to 85 years, with oversampling of men, individuals over age 75, and African Americans and Hispanics. Following the original Round 1 data collection (2005-2006), Round 2 (2010-2011) involved surviving Round 1 respondents as well as a sample of their co-resident partners, and Round 3 (2015-2016) involved returning Round 1 and 2 participants along with newly recruited participants from the Baby Boom cohort. In Round 3, participants over age 60 who had participated in previous NHSAP rounds were asked to complete new measures of elder mistreatment specific to our investigation.11

Social Participation

Participants in Round 3 were asked about formal social participation (i.e., involvement in organized social activities) in the past 12 months in a leave-behind questionnaire.13, 17 Specifically, participants were asked how often they engaged in: (1) volunteering—performing “volunteer work for religious, charitable, political, health-related, or other organizations”; (2) attending organized group meetings—attending “meetings of any organized group (examples included a choir, a committee or board, a support group, a sports or exercise group, a hobby group, or a professional society)”; and (3) attending “religious services.” For all of the above, response options were “several times a week,” “every week,” “about once a month,” “several times a year,” “about once or twice a year,” “less than once a year,” and “never.” Following the precedent of prior work, we categorized respondents as involved in an activity if they reported at least monthly formal social participation in the activity.13, 18, 19 In addition, we categorized participants as “broadly engaged” in organized social activities if they were involved in all three of the above types of activities (organized meeting attendance, volunteering, and religious service attendance) at least once a month.

Informal social participation, or social activity with family and friends, was also assessed by leave-behind questionnaire.17 Participants were asked “how often did you get together socially with friends or relatives” in the past twelve months, with response options again ranging from “several times a week” to “never.”13 Due to the higher frequency of informal social participation observed in NSHAP and other observational studies,16, 20 we used a weekly rather than monthly threshold to identify participants with a high level of informal social participation, focusing on respondents who reported socializing informally “every week” or “several times a week” compared to those who reported less frequent socializing.

Elder Mistreatment

Elder mistreatment was assessed during in-home interviews using questionnaire items derived from a population-based study of older adults.21, 22 Only participants in the Round 1 cohort and aged 60 years or older at the time of the Round 3 interview were asked to complete elder mistreatment questions. Questions were designed to assess multiple forms of mistreatment since turning age 60 with response options “Yes”, “No” or “Don’t Know” (Supplemental Table S1).

For this study, we focused on three domains of mistreatment (emotional, financial, and physical) grouped based on unweighted factor analysis of survey items (Supplemental Table S1) and their congruency with other studies.22 Four items captured emotional mistreatment, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “the infliction of anguish, pain, or distress through verbal or nonverbal acts.”23 Two items captured physical mistreatment, including but not limited to, “acts of violence as striking … hitting, beating, pushing, shoving, shaking, slapping, kicking, pinching, and burning.”23 Two items captured financial mistreatment, the “illegal or improper use of an elder’s funds, property, or assets.”23 Two items previously proposed to correspond with “coercion” were left out because the number of participants reporting this form of mistreatment was low; furthermore, this domain did not conform to prior studies’ and institutional definitions of subtypes of elder mistreatment.22, 23 Participants were considered to have experienced emotional, financial, or physical mistreatment since age 60 if they responded “Yes” to any question in the relevant domain.11

Severity of mistreatment was assessed by asking participants who reported any mistreatment, “How serious of a problem was this for you?” with response options, “not serious,” “somewhat serious,” and “very serious.” Participants who reported any form of mistreatment were asked whether the person “who has done this the most since you turned 60” was on the participant’s social network roster, defined as “people with whom you most often discussed things that were important to you.” 24 The mistreatment was considered to have been perpetrated by a close contact if the participant gave an affirmative response.

Other Participant Characteristics

Other demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed during the NSHAP Round 3 interview. Demographic characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education were self-reported. Physical and mental health were self-reported using a standard single-item measure with response options ranging from “excellent” to “poor.” Participants were asked about prior physician diagnoses of chronic health conditions, with results used to calculate an NSHAP Comorbidity Index score, an overall measure of chronic disease burden, following previously established methods.25, 26 Current religious preference was assessed in a leave-behind questionnaire, with response options including “None,” “Protestant,” “Catholic,” “Christian Orthodox,” “Jewish,” “Muslim,” and “Other.” An 18-item adaptation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-SA) was administered to assess cognitive function—details of which have been previously described.12, 27

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to examine the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics in the analytic sample of men and women, including social participation and elder mistreatment. Chi-square tests and linear regression were used to calculate differences in the distribution of these characteristics between men and women. Bivariate associations and chi-square tests for heterogeneity were used to assess for unadjusted associations between social participation and elder mistreatment. Sampling weights were used to ensure correct calculation of the point estimates, and survey-weighted statistics accounted for non-response by age and race.28

We developed multivariable logistic regression models to examine the strength and direction of associations between social participation and elder mistreatment. All models were stratified by gender, based on analyses indicating differences in patterns of social participation and elder mistreatment among men versus women.6, 15, 29–31 All models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, and NSHAP comorbidity index, as factors chosen a priori for the likelihood that they would be associated with both social participation and elder mistreatment.5, 6, 32 For all analyses examining religious service attendance (including those examining broad formal social engagement), we included participants only if they indicated a specific religious preference (>90% of participants), to avoid bias arising from differential rates of both religious service attendance and elder mistreatment among those with and without a religious preference.

We also conducted supplemental analyses which additionally adjusted for self-reported physical health, mental health, and cognitive status to address prior research indicating that poor physical, mental, and cognitive health are associated with elder mistreatment and could be confounders of associations with mistreatment.8, 32, 33 Although, they could also represent important downstream consequences of mistreatment.34, 35

Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4), and survey procedures (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 2,409 participants eligible to complete elder mistreatment measures, 67 were excluded from analyses because they were under age 60, and 101 were excluded because they did not answer one or more questions about social participation, resulting in an analytic sample of 2,241 participants, including 973 men and 1268 women. Among the analytic sample, the average age was 75 years old for women and 76 years for men (Table 1). Approximately 82% of women and men self-identified as non-Hispanic white. Over 55% of participants reported some college education. Forty-eight percent of women and 23% of men reported being married or living with a partner. Two-thirds of women and 60% of men reported at least one chronic condition assessed by the NSHAP Comorbidity Index. Over 92% of women and 94% of men reported good to excellent mental health. Sixty-six percent of women and 64% of men had normal cognition according to MoCA-SA.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants, by Gender (n = 2241)

| Women (n = 1268) | Men (n = 973) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristica | N or mean | % or SD | N or mean | % or SD | P value |

| Age in years | |||||

| Mean | 75.3 | 0.2 | 75.6 | 0.3 | >.05 |

| Age 60-69 | 271 | 22.0 | 162 | 17.8 | >.05 |

| Age 70-79 | 606 | 51.2 | 513 | 55.6 | |

| Age 80-89 | 343 | 23.9 | 267 | 23.9 | |

| Age 90-99 | 48 | 2.8 | 31 | 2.6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 920 | 82.2 | 718 | 82.0 | >.05 |

| African American | 189 | 9.4 | 123 | 8.2 | |

| Hispanic | 127 | 6.2 | 108 | 6.9 | |

| Other | 26 | 2.3 | 22 | 2.9 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | 215 | 14.3 | 166 | 13.9 | <.001 |

| High school or equivalent | 323 | 26.5 | 219 | 22.3 | |

| Some college | 448 | 36.8 | 262 | 26.0 | |

| Bachelor’s or more | 282 | 22.5 | 326 | 37.8 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married or living with a partner | 570 | 47.7 | 199 | 23.4 | <.001 |

| Separated, divorced, widowed, or never married | 698 | 52.3 | 774 | 76.6 | |

| Religious preference | |||||

| Any religious preference | 1200 | 94.1 | 883 | 90.1 | <.05 |

| Self-reported physical health | |||||

| Poor | 64 | 4.4 | 54 | 5.3 | >.05 |

| Fair | 226 | 16.1 | 184 | 19.0 | |

| Good/Very Good/Excellent | 975 | 79.5 | 732 | 75.2 | |

| Self-reported mental health | |||||

| Poor | 7 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.4 | <.05 |

| Fair | 89 | 7.2 | 57 | 5.2 | |

| Good/Very Good/Excellent | 1049 | 92.4 | 801 | 94.4 | |

| NSHAP Comorbidity Index | |||||

| 0 | 326 | 33.5 | 491 | 40.1 | <.001 |

| 1 | 302 | 31.6 | 442 | 35.2 | |

| 2 | 185 | 19.2 | 212 | 15.9 | |

| 3 | 84 | 7.8 | 81 | 6.10 | |

| 4+ | 76 | 7.9 | 42 | 2.68 | |

| Adapted Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-SA) | |||||

| MoCA-SA > 22 (normal) | 574 | 65.7 | 760 | 64.2 | >.05 |

| MoCA-SA 18-22 (mild cognitive impairment) | 235 | 21.1 | 301 | 23.0 | |

| MoCA-SA <18 (screen positive for dementia) | 164 | 13.2 | 207 | 12.8 | |

Frequencies given as unweighted; Percentages are column percentages and given as weighted

P value compares characteristic values between women and men.

Data were missing for 8 participants for race/ethnicity, 6 participants for self-reported physical health, and 234 for self-reported mental health.

Self-reported prevalence of formal and informal social participation

Self-reported prevalence of formal social participation was higher in women than in men (Table 2) as measured by organized meeting attendance (women: 34% vs. men: 26%, P<.05), religious service attendance (women: 54% vs. men: 49%, P<.05), and volunteering (women: 35% vs. men: 24%, P<0.001). Sixteen percent of women, compared to 11% of men, were broadly engaged in all three forms of formal social participation at least monthly (P<.05).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Formal and Informal Social Participation in the Past 12 Months

| Social Participation Typea | Women (n=1268) | Men (n=973) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Social Participation – Monthly or More Frequent | n | % | n | % | P |

| A) Attendance at organized group meetings | 387 | 33.6 | 251 | 26.4 | <.05 |

| B) Attendance at religious servicesb | 653 | 53.6 | 438 | 48.8 | <.05 |

| C) Volunteer work | 422 | 35.2 | 239 | 24.1 | <.001 |

| Broadly engaged (A, B and C)b,c | 169 | 15.5 | 98 | 11.1 | <.05 |

| Informal Social Participation – Weekly or More Frequent | n | % | n | % | P |

|

| |||||

| Getting together with friends and family | 739 | 67.1 | 480 | 57.2 | <.001 |

Frequencies given as unweighted; Percentages are column percentages and given as weighted

P value compares social participation frequency between women and men.

Data were missing for 3 participants for organized meeting attendance, 3 participants for religious service attendance 13 participants for volunteer work, and 3 participants for getting together with friends and family.

Prevalence estimates for attendance at religious attendance and broad formal social engagement were calculated out of those who indicated having a religious preference.

“Broadly engaged” is defined as participation in all three formal activities at least monthly or more.

Informal weekly social participation was also more common in women than in men. Two-thirds of women versus 57% of men reported at least weekly informal social interactions with friends or family (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Self-reported experience of emotional, physical, and financial mistreatment

Forty percent of women and 22% of men reported at least one form of mistreatment (emotional, physical, or financial) (P>.05) (Table 3). Thirty-one percent of women and 29% of men reported experiencing some form of emotional mistreatment (P>.05). Twenty-percent of women vs. 16% of men reported emotional mistreatment that was somewhat or very serious (P<.05). Nine percent of women vs. 10% of men reported emotional mistreatment by a close contact (P>.05).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Elder Mistreatment by Gender (n = 2241)

| Elder Mistreatmenta,b | Women (n = 1268) | Men (n=973) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Mistreatment | n | % | n | % | P |

| Felt nobody wanted you around | 109 | 8.7 | 63 | 7.4 | >.05 |

| Called you names or put you or down or made you feel badly | 190 | 14.1 | 90 | 8.8 | <.001 |

| Uncomfortable at home with anyone in family | 258 | 20.8 | 201 | 21.1 | >.05 |

| Told you gave them too much trouble | 61 | 5.4 | 46 | 4.5 | >.05 |

| Any of the above | 388 | 31.2 | 267 | 28.5 | >.05 |

| Perpetrated by a Close Contact | 124 | 9.3 | 84 | 9.7 | >.05 |

| Reported as somewhat or very serious | 247 | 20.0 | 155 | 16.2 | <.05 |

| Physical Mistreatment | n | % | n | % | P |

|

| |||||

| Anyone close who tried to hurt or harm you | 31 | 2.7 | 17 | 1.5 | >.05 |

| Afraid of anyone in family | 41 | 3.7 | 6 | 0.7 | .001 |

| Any of the above | 61 | 5.4 | 21 | 1.9 | <.001 |

| Perpetrated by a Close Contact | 13 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.3 | >.05 |

| Reported as somewhat or very serious | 48 | 4.5 | 16 | 1.6 | <.05 |

| Financial Mistreatment | n | % | n | % | P |

|

| |||||

| Taken things that belong to you | 127 | 9.9 | 106 | 9.5 | >.05 |

| Borrowed your money without paying you back | 244 | 17.7 | 225 | 22.9 | <.05 |

| Any of the above | 302 | 22.7 | 275 | 27.5 | <.05 |

| Perpetrated by a Close Contact | 72 | 5.1 | 72 | 4.7 | >.05 |

| Reported as somewhat or very serious | 162 | 12.4 | 123 | 9.2 | >.05 |

| One of more forms of mistreatment | n | % | n | % | P |

|

| |||||

| Emotional, physical, and/or financial mistreatment | 521 | 40.4 | 403 | 22.4 | >.05 |

Frequencies given as unweighted; Percentages are column percentages and given as weighted

P value compares prevalence between women and men.

Data were missing for 8 participants for feeling uncomfortable at home, 9 participants for being told one gave too much trouble, 3 participants for being afraid of someone in their family, 14 participants for feeling nobody wanted them around, 6 participants for being called names or put down, 2 participants who had someone close try to hurt or harm them, 10 participants who had things taken from them, and 9 participants who had money borrowed from them that was not paid back.

Five percent of women and 2% of men reported experiencing some form of physical mistreatment (P<0.001). Five-percent of women vs. 2% of men experienced physical mistreatment that they considered somewhat or very serious (P<.05). Less than 2% of men and women experienced mistreatment perpetrated by a close contact (P>.05).

Over one-fifth of women and one-quarter of men reported some form of financial mistreatment (P<.05). Over 12% of women vs. 9% of men experienced financial mistreatment they considered to be somewhat or very serious (P>.05). Five-percent of women and men reported financial mistreatment from a close contact (P>.05).

Prevalence of elder mistreatment by social participation status

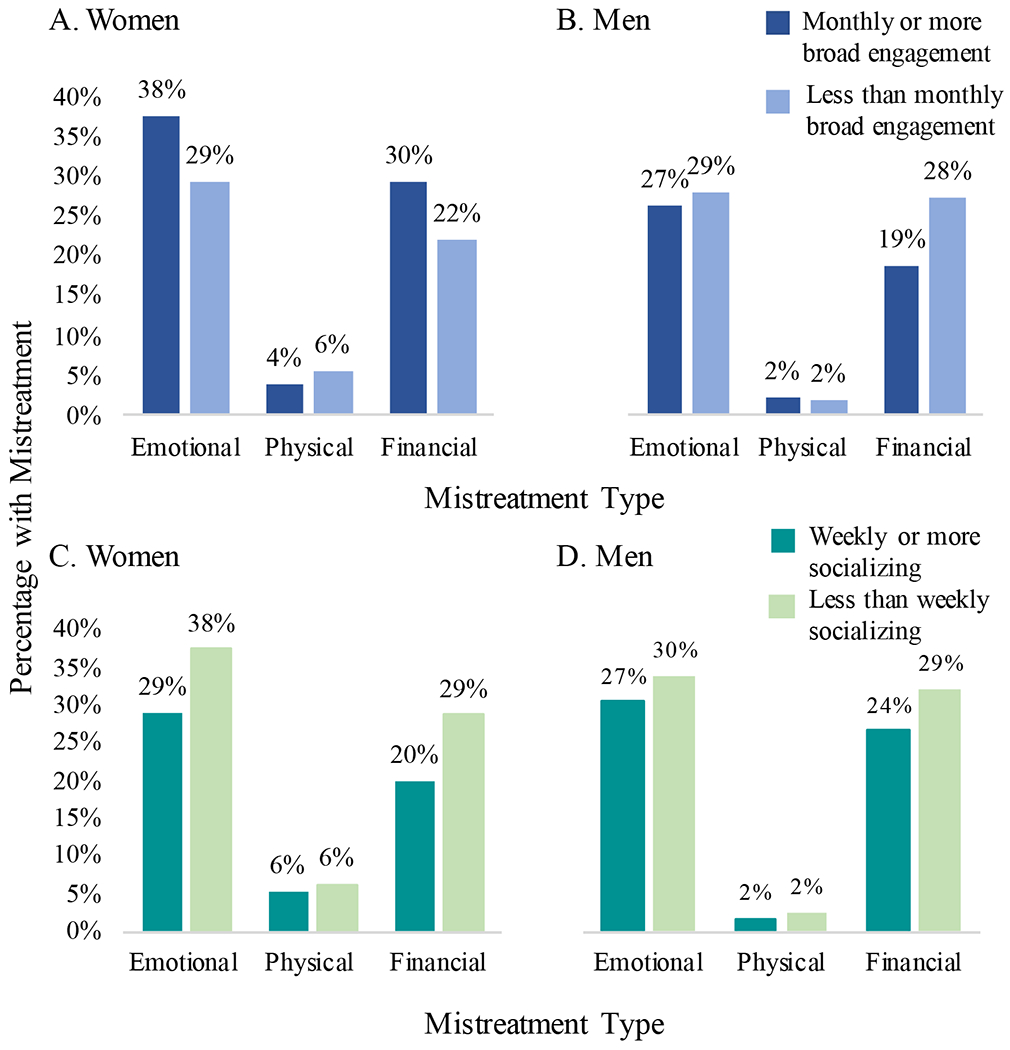

Women who were broadly engaged reported more emotional mistreatment than those less broadly engaged (38% vs. 29%, P<.05) (Figure 1), but no significant differences in physical or financial mistreatment were found in women based on broad social engagement. Women who socialized informally at least weekly or more reported less emotional (29% vs. 38%, P<.05) and financial mistreatment (20% vs. 29%, P<.05) than those reporting less frequent socializing, but no significant differences in physical mistreatment by informal socializing frequency were found.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of elder mistreatment by gender and social participation. A. Elder mistreatment by formal social engagement status among older women. P<.05 for difference in the weighted prevalence of emotional mistreatment between monthly or more and less than monthly broad engagement (among women with a religious preference). P>.05 for physical and financial mistreatment B. Elder mistreatment by formal social engagement status among older men. P>.05 for difference in weighted prevalence of emotional, physical and financial mistreatment between monthly or more and less than monthly broad engagement (among men with a religious preference). C. Elder mistreatment by informal social engagement status among older women. P<.05 for difference in weighted prevalence of emotional mistreatment between weekly or more and less than weekly socializing. P>.05 for financial mistreatment. P<.05 for financial mistreatment. D. Elder mistreatment by informal social engagement status among older men. P>.05 for all forms of mistreatment.

Among men, no significant differences in the prevalence emotional, physical, or financial mistreatment were detected based on frequency of either broad formal social engagement or informal socializing (Figure 1).

Associations between formal social participation and elder mistreatment

After multivariable adjustment in our main models, no significant associations were detected between monthly participation in any one type of organized social activity and elder mistreatment among women (Table 4). However, women who were broadly engaged at least monthly had an estimated 59% increased odds (95% CI 1.09-2.33) of emotional mistreatment vs. women with less than monthly engagement. After additional adjustment for physical and mental health and cognitive status, women who were broadly engaged at least monthly had a 76% increased odds (95% CI 1.15-2.69) of emotional mistreatment (Supplemental Table S2).

Table 4.

Associations Between Social Participation and Elder Mistreatment in Older Women and Men

| Formal Social Participation | Women | Emotional mistreatment | Physical mistreatment | Finanaical mistreatment |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Attendance at organized meetings | 1.19(0.88-1.61) | 1.29(0.64-2.60) | 1.24(0.84-1.83) | |

| Attendance at religious servicesa,b | 0.99 (0.75-1.33) | 0.83 (0.42-1.60) | 0.88 (0.69-1.12) | |

| Community volunteer work | 1.28 (0.97-1.70) | 1.22 (0.64-2.30) | 1.14 (0.85-1.54) | |

| Broad engagement in all activitiesa | 1.59 (1.09-2.33) | 0.79 (0.26-2.40) | 1.53 (0.98-2.38) | |

| Men | Emotional mistreatment | Physical mistreatment | Finanaical mistreatment | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Attendance at organized meetings | 1.34 (1.01-1.93) | 0.56 (0.16-2.01) | 1.33 (0.90-1.97) | |

| Attendance at religious servicesa | 1.23 (0.89-1.71) | 1.17 (0.39-3.50) | 0.65 (0.90-1.97) | |

| Community volunteer work | 1.08 (0.74-1.58) | 1.04 (0.31-3.55) | 0.89 (0.59-1.34) | |

| Broad engagement in all activitiesa,b | 0.92 (0.50-1.70) | 1.03 (0.26-4.14) | 0.65 (0.32-1.30) | |

| Informal Social Participation | Women | Emotional mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Physical mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Financial mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Socializing with friends and family | 0.59 (0.44-0.78) | 0.97 (0.43-2.16) | 0.59 (0.42-0.85) | |

| Men | Emotional mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Physical mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Financial mistreatment Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Socializing with friends and family | 0.86 (0.55-1.33) | 1.29 (0.19-8.78) | 0.82 (0.55-1.24) |

OR = Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Bolded results indicate p < .05.

Models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, and NSHAP Comorbidity Index

For models examining attendance at religious services or broad engagement in all formal social activities, analyses were restricted to participants who reported a religious preference.

Defined by involvement in all three forms of formal social participation at least monthly.

Associations involving formal social participation compare participants with monthly or more with participants with less than monthly involvement . Associations involving informal social participation compare individuals with weekly or more socializing with less than weekly socializing.

No significant differences in the odds of financial or physical mistreatment were detected between women with and without monthly broad engagement.

Older men who attended organized meetings at least monthly had an estimated 34% increased odds (95% CI 1.01-1.93) of emotional mistreatment compared to men with less than monthly attendance after adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, education, and comorbidity score (Table 4). After additional adjustment for physical, mental, and cognitive health, older men who attended organized meetings at least monthly had a 53% increased odds (95% CI 1.11-2.12) of emotional mistreatment compared to men with less than monthly attendance (Supplemental Table S2).

No significant associations were detected between religious service attendance or volunteering and any form of mistreatment among men in models adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, education, and comorbidity score. However, with additional adjustment for physical, mental, cognitive health, older men who attended religious services at least monthly vs. less than monthly had a 41% decreased odds (95% CI 0.37-0.92) of financial mistreatment (Supplemental Table S2).

No significant associations were observed between broad engagement and emotional, physical or financial mistreatment among older men.

Associations between informal social participation and elder mistreatment

Women who reported socializing at least weekly with family or friends had an estimated 41% decreased odds (95% CI 0.44-0.78) of reporting emotional mistreatment and 41% decreased odds (95% CI 0.42-0.85) of reporting financial mistreatment since age 60 in the main models (Table 4).

After additional adjustment for physical, mental and cognitive health, no significant associations were detected between socializing and any form of mistreatment in women (Supplemental Table S2).

Among older men, no significant associations were detected between informal social participation with family or friends and emotional, physical or financial mistreatment in main or supplemental multivariable-adjusted models (Table 4; Supplemental Table S2).

Discussion

Findings from this nationally-representative cohort of community-dwelling older adults provide new and, in some cases, unexpected insights into the relationships between different forms of social participation and elder mistreatment. Contrary to our hypotheses, older adults who reported more frequent formal social participation did not report lower levels of elder mistreatment. In fact, older women who were more broadly engaged were more likely to report emotional mistreatment than women who engaged in these activities less frequently, even after adjustment for physical, mental, and cognitive health . Older men who attended organized meetings at least monthly were also more likely to report emotional mistreatment than men who attended less frequently, even after adjustment for physical, mental, and cognitive health.

One possible explanation is that older adults who are engaged in more organized community activities have more contact points for mistreatment. With wider social engagement, older adults have more opportunities for not only positive but also negative interpersonal interactions. Prior studies have reported mixed findings about the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim, with some suggesting that perpetrators tend to be relatives or those living in the same household,21 but others suggesting that perpetrators are more likely to be outside the older adult’s household.11, 29 Our findings suggest that a substantial minority of perpetrators are among the close contacts of older adults, but many adults may have experienced mistreatment from occasional encounters with acquaintances or strangers. For older adults frequently involved in community activities, the source of mistreatment could be individuals whom they see regularly outside their home.

Another possibility is that social activities are not themselves a source of mistreatment, but instead represent an opportunity for older adults to seek social support in response to abuse. From NSHAP Round 3, we cannot determine the timing between older adults’ engagement in social activities (assessed in the past year) and their experience of mistreatment. Elder mistreatment questions assessed mistreatment experienced since age 60 and did not characterize the chronicity of such events (e.g. whether the mistreatment was ongoing). Older adults who experienced mistreatment may have responded by engaging in more community activities as a coping mechanism or in an effort to establish alternate or more supportive social relationships.

Our findings are relevant to ongoing research on social prescribing as an intervention for social isolation and loneliness.11 Social prescribing connects patients (typically in an outpatient setting) with community support, such as adult-day programs, skill-based activities, and advocacy services. However, clinicians and geriatric researchers have recently identified the need for further work on identifying and mitigating “unintended consequences” of social prescribing. 36 Though our study does not examine social prescribing specifically, it reveals the potential harm of greater mistreatment after social prescribing for lonely older adults and highlights the importance of follow-up after initiation of these programs.

Most importantly, our findings indicate that clinicians and allied workers cannot assume that older adults actively engaged in community organizations, religious services, or volunteering are not at risk of elder mistreatment. In fact, they may be more likely to suffer from some forms of abuse than those who are less engaged in these activities. While community social engagement has been shown to have physical and mental health benefits,20, 37, 38 our study suggests that practitioners caring for older adults should be alert to social participation that can lead to negative experiences like elder mistreatment.

On the other hand, we found that older women who reported at least weekly informal social interactions with friends and family were less likely to report emotional and financial mistreatment. This relationship did not persist after additional adjustment for cognitive, physical, and mental health. Nevertheless, our results suggest a potentially protective effect of informal socializing against mistreatment, which could be explained by differences in mental and physical function resulting from or associated with frequent social interactions with friends and family.

Among older men, we did not find that frequent socializing with friends or family served as a buffer against mistreatment. Because older women generally have higher levels of social participation and tend to report more mistreatment,39, 40 it is possible that a protective relationship, if existent, was easier to detect in older women than in older men. Prior research has also suggested that older women tend to experience a larger health benefit from social activities than men.15 Further research is needed to evaluate gender differences in the relationship between informal social participation and elder mistreatment.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, which prevents us from establishing causal relationships or examining longitudinal changes in associations, although it may permit some inferences. Older adults’ social behaviors may have increased or decreased their risk of mistreatment, but their experience of mistreatment may also have influenced their social activities. Our ability to detect associations between social participation and physical mistreatment may have been limited by the relatively low reported prevalence of physical mistreatment in this population. Older adults in this sample were generally healthy and potentially less vulnerable to some forms of elder mistreatment.41

Furthermore, NHSAP Round 3 data collection took place before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has not only drastically curtailed older adults’ social interactions with those outside of their own households, but also created new stressors that may affect their susceptibility to abuse. Recent events have added urgency to the discussion about social isolation and its health impact;2, 42 the associations observed in this study are likely relevant to both the pre- and post-COVID-19 world.

Overall, our study suggests that clinicians need to give careful consideration to the complex ways in which social activities can both contribute to or mitigate harm from elder mistreatment. This suggested approach addresses the ecological context pillar of Abuse Intervention Model proposed to address salient and modifiable risk factors for mistreatment.10

In addition to utilizing screening tools for elder mistreatment, clinicians may ask older adults’ about their social participation patterns to assess risk of mistreatment and identify potential perpetrators and/or confidants. Clinicians and allied health professionals, such as social workers, with longitudinal relationships with patients may be in the best position to elucidate the nature of older adults’ relationships in both formal and informal social interactions. When positive relationships are discerned, clinicians may encourage older adults to maintain these positive relationships and stay engaged in beneficial activities. When negative relationships are identified, clinicians may help the adult consider alternatives to harmful environments and formulate a plan for advocacy and protection.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1. Survey Items for Emotional, Physical and Financial Mistreatment

Emotional mistreatment since age 60 was assessed with four survey items, physical mistreatment since age 60 with two survey items, and financial mistreatment since age 60 with two survey items.

Supplemental Table S2. Associations Between Social Participation and Elder Mistreatment in Older Women and Men (With Adjustments for Self-Reported Physical, Mental and Cognitive Health)

Key Points:

In this national cohort, older adults who frequently engaged in formal social activities reported similar or higher levels of mistreatment than those with less frequent participation.

However, older women with regular informal contact with family or friends were less likely to report some kinds of elder mistreatment.

When taking a social history, clinicians should consider the potentially complex ways in which older adults’ social activities may both contribute to and protect against from elder mistreatment.

“Why does this matter?”.

These findings raise the possibility that older adults’ social participation may be both a risk factor for mistreatment and a protective factor against it. Clinicians should assess both formal and informal social participation when screening for or trying to prevent elder mistreatment.

Sponsor’s Role:

The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project was funded by National Institute of Aging and National Institute of Health grants R01AG043538, R01AG048511 and R37AG030481. Ms. Emmy Yang was supported by the American Federation on Aging Research’s Medical Student Training in Aging Research Program (5T35AG026736-13). Dr. Ashwin Kotwal’s effort was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG065438; R03AG064323), the NIA Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG044281), the National Palliative Care Research Center Kornfield Scholar’s Award, and the Hellman Foundation Award for Early-Career Faculty. Dr. Alison Huang was supported by NIA grant K24AG068601.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Klein E Coronavirus will also cause a loneliness epidemic. Vox. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cudjoe TKM, Kotwal AA. “Social Distancing” Amid a Crisis in Social Isolation and Loneliness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Beach SR, Schulz R, Sneed R. Associations Between Social Support, Social Networks, and Financial Exploitation in Older Adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37: 990–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schafer MH, Koltai J. Does embeddedness protect? Personal network density and vulnerability to mistreatment among older American adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70: 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100: 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63: S248–S254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Anetzberger GJ, Loew D, Muzzy W. The National Elder Mistreatment Study: An 8-year longitudinal study of outcomes. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2017;29: 254–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dong X, Simon M, Mendes de Leon C, et al. Elder self-neglect and abuse and mortality risk in a community-dwelling population. JAMA. 2009;302: 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dong XQ. Elder Abuse: Systematic Review and Implications for Practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63: 1214–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mosqueda L, Burnight K, Gironda MW, Moore AA, Robinson J, Olsen B. The Abuse Intervention Model: A Pragmatic Approach to Intervention for Elder Mistreatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64: 1879–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wong JS, Breslau H, McSorley VE, Wroblewski KE, Howe MJK, Waite LJ. The Social Relationship Context of Elder Mistreatment. Gerontologist. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kotwal AA, Kim J, Waite L, Dale W. Social Function and Cognitive Status: Results from a US Nationally Representative Survey of Older Adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31: 854–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Santini ZI, Jose PE, Koyanagi A, et al. Formal social participation protects physical health through enhanced mental health: A longitudinal mediation analysis using three consecutive waves of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Soc Sci Med. 2020;251: 112906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Waite L, Das A. Families, social life, and well-being at older ages. Demography. 2010;47 Suppl: S87–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thomas PA. Gender, social engagement, and limitations in late life. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73: 1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cornwell B, Goldman A, Laumann EO. Homeostasis Revisited: Patterns of Stability and Rebalancing in Older Adults’ Social Lives. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Howrey BT, Hand CL. Measuring Social Participation in the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2019;59: e415–e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gao M, Sa Z, Li Y, et al. Does social participation reduce the risk of functional disability among older adults in China? A survival analysis using the 2005–2011 waves of the CLHLS data. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18: 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hand CL, Howrey BT. Associations Among Neighborhood Characteristics, Mobility Limitation, and Social Participation in Late Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74: 546–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. J Aging Health. 2012;24: 547–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dong X, Wong E, Simon MA. Study design and implementation of the PINE study. J Aging Health. 2014;26: 1085–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dong X, Wang B. Incidence of Elder Abuse in a U.S. Chinese Population: Findings From the Longitudinal Cohort PINE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72: S95–S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hall JE KD, Crosby AE. Elder Abuse Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Reccommended Core Data Elements for Use in Elder Abuse Surveillance, Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cornwell B, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Kim J, Kim Y-J. Assessment of social network change in a national longitudinal survey. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2014;69 Suppl 2: S75–S82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vasilopoulos T, Kotwal A, Huisingh-Scheetz MJ, Waite LJ, McClintock MK, Dale W. Comorbidity and chronic conditions in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), Wave 2. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 2: S154–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kotwal AA, Walter LC, Lee SJ, Dale W. Are We Choosing Wisely? Older Adults’ Cancer Screening Intentions and Recalled Discussions with Physicians About Stopping. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34: 1538–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kotwal AA, Schumm P, Kern DW, et al. Evaluation of a Brief Survey Instrument for Assessing Subtle Differences in Cognitive Function Among Older Adults. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29: 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Kwok PK. Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 2: S15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Amstadter AB, Cisler JM, McCauley JL, Hernandez MA, Muzzy W, Acierno R. Do incident and perpetrator characteristics of elder mistreatment differ by gender of the victim? Results from the National Elder Mistreatment Study. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2011;23: 43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].WIlson J. Volunteering. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26: 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sherkat DE, Ellison CG. Recent Developments and Current Controversies in the Sociology of Religion. Annu Rev Sociol. 1999;25: 363–394. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pillemer K, Burnes D, Riffin C, Lachs MS. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist. 2016;56 Suppl 2: S194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lachs MS, Williams C, O’Brien S, Hurst L, Horwitz R. Risk factors for reported elder abuse and neglect: a nine-year observational cohort study. Gerontologist. 1997;37: 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wong JSM, Waite LJP. Elder mistreatment predicts later physical and psychological health: Results from a national longitudinal study. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2017;29: 15–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dong X, Simon M, Beck T, Evans D. Decline in Cognitive Function and Elder Mistreatment: Findings from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;22: 598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Savage RD, Stall NM, Rochon PA. Looking before we leap: building the evidence for social prescribing for lonely older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68: 429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ang S Social participation and health over the adult life course: Does the association strengthen with age? Soc Sci Med. 2018;206: 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Association Between Social Participation and 3-Year Change in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65: 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Finkel D, Franz CE, Horwitz B, et al. Gender Differences in Marital Status Moderation of Genetic and Environmental Influences on Subjective Health. Behav Genet. 2016;46: 114–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dong X Do the definitions of elder mistreatment subtypes matter? Findings from the PINE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 2: S68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cornwell B, Laumann EO, Schumm LP. The Social Connectedness of Older Adults: A National Profile*. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73: 185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Han SD, Mosqueda L. Elder Abuse in the COVID-19 Era. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Survey Items for Emotional, Physical and Financial Mistreatment

Emotional mistreatment since age 60 was assessed with four survey items, physical mistreatment since age 60 with two survey items, and financial mistreatment since age 60 with two survey items.

Supplemental Table S2. Associations Between Social Participation and Elder Mistreatment in Older Women and Men (With Adjustments for Self-Reported Physical, Mental and Cognitive Health)