Summary Statement:

From preoperative medications to intraoperative needs to postoperative thromboprophylaxis, anticoagulants are encountered throughout the perioperative period. This review will focus on coagulation testing clinicians utilize to monitor the effects of these medications.

Introduction

Anticoagulants form one arm of antithrombotic therapy, the other being anti-platelet agents.1 The common mechanism of action of these medications is preventing fibrin formation by inhibiting one or more steps along the coagulation cascade. Although warfarin and heparin were the mainstay oral and parenteral anticoagulants of the 20th century, today’s perioperative clinicians are faced with other unique classes of agents. Specifically, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are now available to inhibit Factor Xa or thrombin. This presents a challenge in monitoring since the effects of these newer agents on standard testing do not always reflect the degree of anticoagulation being achieved within the patient.

This focused review will detail the most common coagulation tests used to assess the level of patient anticoagulation. These will be organized into tests obtained from the central laboratory which are often ordered pre- or post-operatively, and those that are considered point-of-care and typically used in the operating room or at the ICU bedside (see Table 1). Finally, some unique monitoring considerations when transitioning between classes of agents will be considered.

Table 1:

Common Anticoagulants and Monitoring Assays

| Parenteral Agents | Oral Agents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparins | DTIs | VKAs | DTIs | Xa Inhibitors | ||

| LAB | PT/INR | Possible Interference |

Possible Interference |

Quantitative | Possible Interference |

Possible Interference |

| PTT |

Semi-Quantitative

sensitive to Factor VIII & acute phase reactants |

Semi-Quantitative

poor correlation with drug levels |

Possible Interference |

Exclusionary

lab reagent dependent |

Possible Interference |

|

| TT / diluteTT |

Exclusionary

normal values can exclude presence of unfractionated, but not low molecular weight, heparin |

Exclusionary (TT) | - | Exclusionary (TT) | - | |

|

Quantitative (diluteTT)

sensitive to fibrinogen levels |

Quantitative (diluteTT)

sensitive to fibrinogen levels |

|||||

| Ecarin Assays | - |

Quantitative

Limited availability |

- |

Quantitative

Limited availability |

- | |

| Chromogenic Anti-Xa Assay | Quantitative | - | - | - |

Quantitative

(with special calibrators) |

|

|

Exclusionary

(using heparin calibrator) | ||||||

| POC | Activated Clotting Times |

Semi-Quantitative

high dose monitoring; multiple confounders |

Semi-Quantitative

non-linear relationship at high doses |

Possible Interference |

Possible Interference |

Possible Interference |

| Viscoelastic Testing |

Exclusionary

limited evidence for dosing heparin therapy |

modified reagents are currently under investigation | Possible Interference |

Possible Interference |

modified reagents are currently under investigation | |

Tests are designated as either Quantitative (green) or Semi-Quantitative (yellow) for a specific agent if an actual drug level or some ordinal magnitude of clinical effect can be determined. The Exclusionary designation was given if normal values of the test would rule out clinically significant effects of the anticoagulant. When interpreting the test, clinicians should be aware of the agents in red boxes, labeled “possible interference,” which can interfere with the interpretation of the actual drug level being measured. Boxes with “-“ have no effect on the test or are not generally utilized in the presence of the listed agent. LAB = central laboratory, POC = point-of-care, DTI = direct thrombin inhibitors, VKAs = vitamin K antagonists, Xa Inhibitors = Factor Xa inhibitors, PT = prothrombin time, INR = international normalized ration, PTT = activated partial thromboplastin time, TT and diluteTT = thrombin time and dilute thrombin time, Ecarin assays include the ecarin clotting time and ecarin chromogenic assay.

Central Laboratory Coagulation Testing

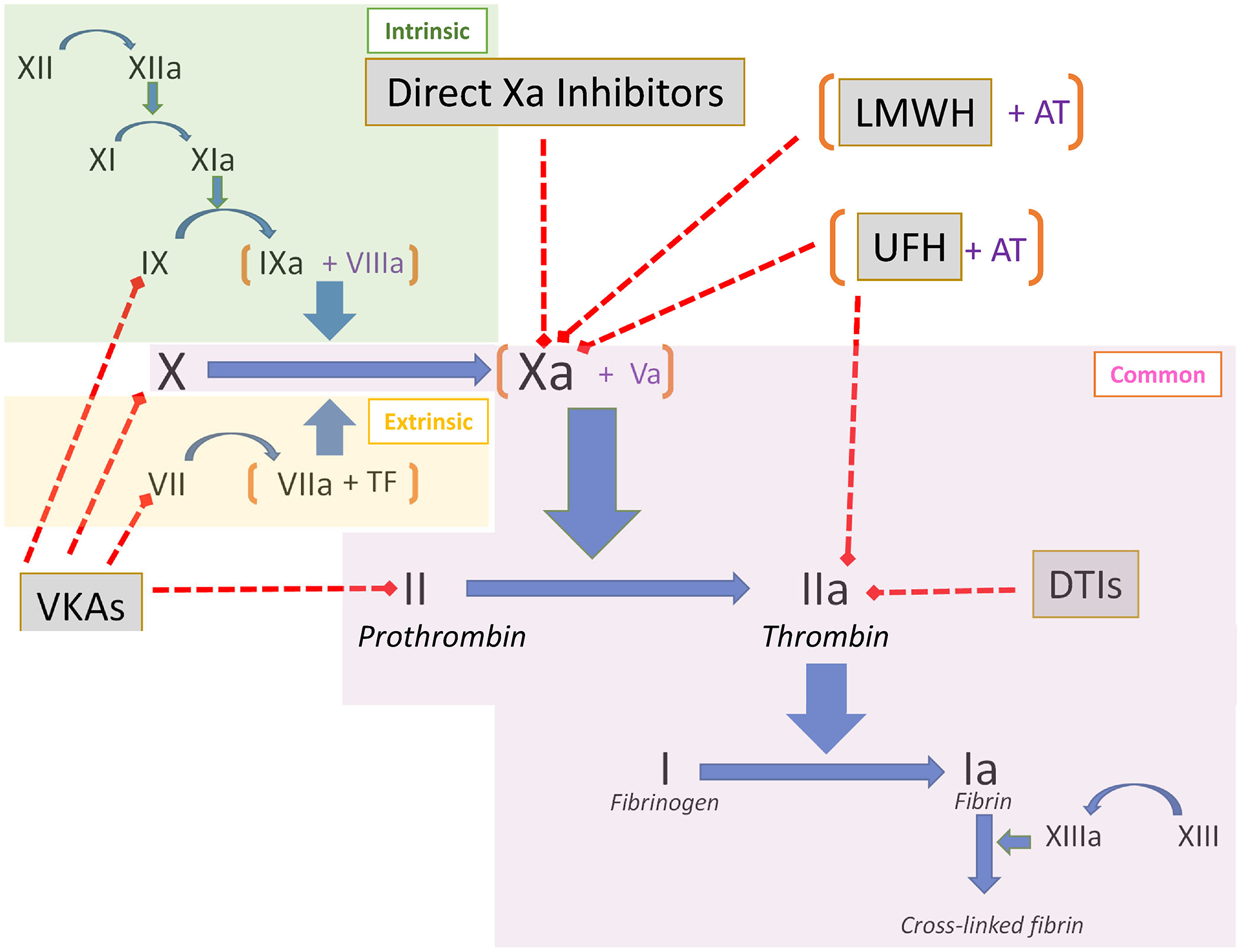

Drug-specific testing to determine clearance kinetics of certain anticoagulants may have a role in elective and controlled settings, yet such tests are often limited by poor availability and long turnaround times. In contrast, urgent or emergency interventions require perioperative physicians to determine whether an anticoagulant effect is present very quickly. Doing so with traditional coagulation tests has become more complicated over the past decade with the introduction DOACs, including direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) like dabigatran, and factor Xa inhibitors like apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban. These agents have variable effects on traditional coagulation testing.2 Nevertheless, central laboratory tests are often the first-line assays obtained and understanding an anticoagulant’s site of action is important when considering how the medication affects them. An overview of the coagulation cascade with relevant targets of anticoagulation therapy is presented in Figure 1. Although the division of the coagulation cascade into three pathways – extrinsic, intrinsic, and common – is a non-physiologic delineation, it can be helpful in the interpretation of hemostasis tests, especially when trying to understand whether a specific inhibitor (i.e., anticoagulant) is present.

Figure 1: Coagulation Cascade with Common Anticoagulant Agent Targets.

The intrinsic (green), extrinsic (yellow), and common (purple) pathways of the coagulation cascade are highlighted. The targets of anticoagulant agents (grey boxes) and denoted by red dashed lines with boxed ends. In general, tests using activators to stimulate the cascade at or proximal to the drug target will be affected by the drug. Coagulation factors are shown in Roman numerals. VKA = vitamin K antagonists, LMWH = low molecular weight heparin, UFH = unfractionated heparin, AT = antithrombin, DTIs = direct thrombin inhibitors.

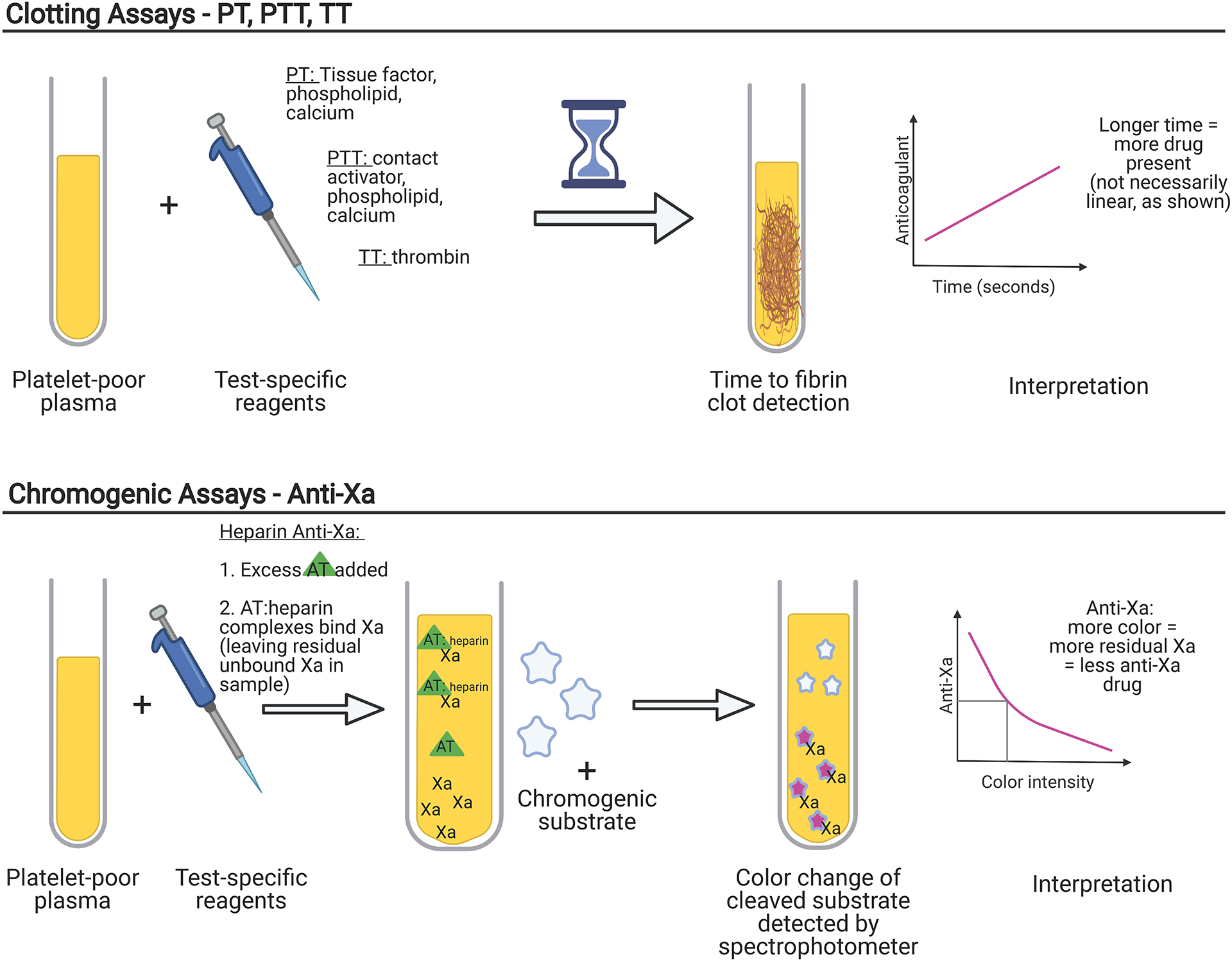

When reviewing laboratory-based coagulation tests it is important to consider whether the assay is clot-based or chromogenic. Most standard coagulation tests, like the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), are clot-based assays, often referred to as one-stage assays. Clot-based assays are sensitive to the effects of other components responsible for fibrin formation in the plasma, as the reaction time is dependent on multiple steps that ultimately result in clotting. Prolongation may reflect deficiencies of involved clotting factors or the presence of factor inhibitors.3 In contrast, chromogenic assays use specific factor substrates bound to a chromophore and release a colored compound when cleaved that is proportional to the amount of factor present. Chromogenic assays are thus less sensitive to low levels of other coagulation factors or to the presence of certain non-specific inhibitors, such as a lupus anticoagulant.4 The basic principles of clot-based testing and chromogenic testing are illustrated in Figure 2. Coagulation factors, such as Factor VIII, Factor IX, Factor X, Factor XIII, as well as antithrombin (AT), plasminogen, and Protein C can be measured via chromogenic assays. Specific assays also exist for anticoagulants such as heparin, apixaban, and rivaroxaban. The major limitation of chromogenic tests for monitoring Xa inhibitors is the need for comparison to a drug-specific standard curve to generate a result, thereby necessitating laboratory awareness of which anticoagulant the patient is on.5 In addition, chromogenic assays are affected by the opacity of the sample, so samples that are icteric, lipemic and/or hemolyzed may generate inaccurate results.

Figure 2: Comparison of Clotting Assays and Chromogenic Assays.

Both laboratory clotting assays and chromogenic assays utilize patient poor plasma, which requires centrifugation of whole blood samples. Test specific reagents are then added. In clot-based assays, the time to fibrin formation, which may be detected by mechanical, turbidimetric, or other means, is measured and compared to a standard nomogram. In chromogenic assays, Factor Xa (Xa) cleaves a chromogenic substrate; the more Xa that is inhibited, the less substrate is cleaved, creating less color to be detected by a spectrophotometer. The interpretation of a drug level is inverse to the amount of color intensity. PT = prothrombin time, PTT = partial thromboplastin time, TT = thrombin time, AT=antithrombin.

Prothrombin Time (PT) and International Normalized Ratio (INR)

The development of the PT is widely credited to Professor Armand Quick (the “Quick time”) in 1935,6 making it one of the oldest coagulation tests still in use. It is a clot-based assay to which thromboplastin (tissue factor, phospholipid, and calcium) is added to citrated platelet poor plasma. Decreased levels of prothrombin, Factor V, Factor VII, Factor X, and fibrinogen (i.e., the extrinsic and common pathways) will result in PT prolongation. The ability to detect decreased factors can depend on the type of thromboplastin used, but in general the PT is most sensitive to low levels of Factor VII and Factor X.3 Since multiple thromboplastin reagents exist, the INR was developed to standardize the measurement between different labs. INR = (PTsample / PTcontrol)ISI, where ISI (international sensitivity index) is calculated based upon a reference thromboplastin. It should be noted that the INR is not a linear scale; the magnitude of difference between 2.0 and 3.0 is not the same as that between 3.0 and 4.0.7

Since several factors affecting the PT are vitamin-K dependent (prothrombin, Factor VII, Factor X), it is not surprising that it is the monitoring test of choice for Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) such as warfarin, phenprocoumon and acenocoumarol. As can be inferred from Figure 1, therapeutic doses of heparin can also prolong the PT, although many commercially available reagents include a heparin neutralizer to prevent this interference. The effect of DOACs on the PT are variable based upon the specific component reagents used. Although oral Xa inhibitors generally prolong the PT more than DTIs,2 the test is not recommended to exclude clinically relevant drug levels of either type of agent.8

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT)

Like the PT, the PTT is a clot-based assay using platelet poor plasma that has been incubated with a surface activator such as kaolin, silica, ellagic acid or celite.3 As the name suggests, this is an incomplete thromboplastin devoid of tissue factor. The activator binds to Factor XII and generates Factor XIIa, which cleaves Factor XI to Factor XIa, but further continuation of the cascade cannot occur in the absence of calcium. The reaction time of the PTT begins with the addition of calcium, allowing for continuation of the cascade, and concludes with fibrin clot formation. The PTT reflects activities of factors involved in the intrinsic and common pathways of coagulation (Figure 1), although it is particularly sensitive to levels of Factor VIII. The PTT reagents can be formulated to be either more or less sensitive to lupus anticoagulant as well. Unlike the INR for the PT, no standardized measurement exists between different laboratories, so values cannot be transposed across institutions.

The PTT historically has been used to monitor heparin therapy. The common practice of assuming an adequate heparin level when the PTT is 1.5 – 2.5 times the laboratory “normal” value is based upon a 1972 observational study of only 254 patients.9 Unfortunately, the PTT’s relationship with the amount of heparin present can be altered by a number of biological variables. The presence of acute phase reactants, especially Factor VIII and fibrinogen, can essentially “normalize” the PTT despite high levels of heparin present. Conversely, some antiphospholipid antibodies (i.e. lupus anticoagulants) can result in an elevated PTT despite minimal heparin present.10 Because of this inconsistent relationship, both the College of American Pathologists and the American College of Chest Physicians recommend individual institutions set PTT goals based upon heparin levels measured by their own clinical laboratories using some other means.11, 12 More recently, the parenteral DTIs bivalirudin and argatroban have also been monitored using PTTs, with many institutional protocols utilizing a target of 1.5 – 2.5 times the control PTT, similar to heparin.13, 14 However, correlation of PTT prolongation with levels of parenteral DTIs measured using tandem mass spectrometry has been noted to be quite poor.15 It is worth noting that while a normal PTT would typically exclude clinically relevant levels of dabigatran, it does not rule out clinically relevant levels of the oral Xa inhibitors.8

Thrombin Time (TT)

The TT involves adding thrombin, from either human or bovine sources, to platelet poor plasma and measuring the time to fibrin clot formation.3 The Clauss assay is actually a modified TT using high concentrations of thrombin and dilute patient plasma; time to clot formation is inversely related to fibrinogen concentration. The standard TT is very sensitive to any type of thrombin inhibition and may have a role in ruling out significant DTI levels in the perioperative period. A normal TT can exclude the presence of clinically relevant concentrations of DTIs or unfractionated heparin, but not low molecular weight heparin since Factor X is not involved in the assay (see Figure 1).16 Patients with decreased levels of fibrinogen, hypoalbuminemia, or high levels of fibrin degradation products can prolong the TT. Thus, an elevated TT does not confirm the presence of a DTI. More quantitative assessment of DTI levels can be made with a plasma-diluted TT for which commercial kits are available. The dilute TT essentially dilutes the patient sample 4–5 times the standard TT, decreasing the sensitivity of the test to DTI presence. The dilute TT has been found to correlate with DTI levels much better than the PTT.15

Ecarin Clotting Time and Ecarin Chromogenic Assay

Ecarin is derived from the venom of the snake Echis carinatus and converts prothrombin (Factor II) into meizothrombin, which is still able to convert fibrinogen to fibrin, but has only about 10% of thrombin’s procoagulant activity.17 Although heparins do not affect meizothrombin, both oral and parenteral DTIs do. The testing advantage of using ecarin for DTI monitoring is that, unlike the aPTT, there is a linear relationship between the amount of meizothrombin inhibited and the quantity of DTI present throughout a wide range of drug concentration. Ecarin can be utilized in a clot-based assay or a chromogenic one.18 The major advantage of the ecarin chromogenic assay is that it is not affected by patient fibrinogen levels. Unfortunately, neither ecarin test is widely available. However, some point-of-care assays for viscoelastic testing are in development (see below).

Anti-Xa Assay

Anti-Xa tests are functional assays that measure the inhibitory activity against Factor Xa in platelet poor plasma. Its use is increasingly widespread for monitoring anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin, which has both anti-Xa and anti-IIa activity, or low molecular weight heparin, which has primarily anti-Xa activity. In the test, platelet poor plasma is incubated with a fixed amount of exogenous Factor Xa and then residual Xa activity, which is inversely proportional to the amount of anticoagulant in the patient sample, is measured. This is most commonly performed using a Factor Xa-specific chromogenic substrate. The result is quantified by comparison to a standard curve generated using dilutions of the specific anticoagulant (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin) and normal plasma.

Chromogenic anti-Xa tests for heparins are similar to the drug-specific anti-Xa tests used to measure fondaparinux, apixaban, or rivaroxaban, with the major difference being the use of drug-specific calibration standards to generate the standard curve for derivation of the patient level. It is important to note that an uncalibrated (or heparin-calibrated) anti-Xa assay cannot be used quantify levels of other Xa inhibitor drugs like apixaban or rivaroxaban, as the standard curve used to determine drug level in each anti-Xa assay is generated using dilutions of the specific anticoagulant or calibrator. It is thus imperative that clinical laboratories know what specific anti-Xa drug a patient is on, and that clinicians understand what anti-Xa testing is available at their center. In the absence of drug-specific anti-Xa test availability, a heparin-calibrated anti-Xa assay may be helpful in determining whether an anticoagulant effect is present in a patient on a DOAC in an emergency situation. For example, we previously reported on the excellent positive correlation between heparin-calibrated anti-Xa test results with apixaban- or rivaroxaban-calibrated anti-Xa test results in patients at our institution taking apixaban or rivaroxaban, respectively (apixaban, n=103, R2=0.9662, p<0.0001; rivaroxaban, n=99, R2=0.9755, p<0.0001).19 However, each laboratory needs to validate this approach since reagents can differ between institutions.20 Perioperative physicians should familiarize themselves with the anti-Xa testing platforms available at their center, including whether generalizable cutoff values for a stat heparin-calibrated anti-Xa assay may be used to exclude significant drug effects from Xa inhibitors like apixaban or rivaroxaban. The construction of linear regression equations can be used to predict levels of apixaban or rivaroxaban from heparin-calibrated anti-Xa curves. In particular, derived cut-offs predicting drug concentrations of 50 ng/ml and 30 ng/ml are useful for considering the administration of reversal agents for actively bleeding and for urgent/emergent high-risk surgical procedures, respectively.21, 22

Similar to anti-Xa assays, there are anti-protease anti-IIa assays that use a chromogenic substrate for specific determination of thrombin inhibition of anticoagulants, including heparin. As noted above, unfractionated heparin has significant anti-IIa activity in addition to anti-Xa activity, while low molecular weight heparin does not. Thus, anti-IIa assays may be useful in the setting of unfractionated heparin monitoring in patients with recent oral anti-Xa inhibitor exposure, which would greatly impact anti-Xa assays.23 Direct thrombin inhibitors could also be measured using anti-IIa assays, although drug-specific tests based on the dilute TT are much more common in current practice.

Point-of-Care Testing

Point-of-care testing for anticoagulation monitoring is generally used when rapid turn around times are required for dynamic situations that can occur in the operating room or interventional suite. These tests use whole blood, eliminating the need for centrifugation of samples to generate platelet poor plasma, which alone generally requires 10–20 minutes. The increased speed and simplicity of collection comes at the cost of introducing other blood elements which can affect coagulation measurements, primarily red blood cells and platelets. Several different point-of-care devices exist for obtaining PT/INR and PTT results; yet it should be noted that these instruments have greater imprecision and may show significant bias compared to their central laboratory counterparts.24, 25 The British Society of Haematology recommends that institutions assess point-of-care INR and PTT results for comparability with central laboratory results and develop algorithms for confirmation of supra-therapeutic levels.26 For these reasons, utilization of point-of-care PT/INR and PTT is highly institution dependent and their advantages in the perioperative setting are unclear. However, two coagulation assays that are utilized almost exclusively as point-of-care tests are activated clotting times and viscoelastic tests.

Activated Clotting Time

The activated clotting time first reported by Paul Hattersley in 1966 was a celite-activated whole blood clotting assay that used the operator’s eyes to detect the first sign of clot formation.27 Modern devices now utilize a wide variety of activators including celite, kaolin, and glass, among other agents. Clot is no longer detected by the naked eye, but via mechanical, optical, and electrochemical means.28 No gold-standard activated clotting time measurement exists and, given the wide array of activators found in the many available devices, comparison of values between institutions is problematic. Reported correlation coefficients of heparinized samples between different devices generally range between 0.7 and 0.9, with differences up to 70 s as the level of anticoagulation increases.29–31 It is therefore not surprising that target activated clotting time values for initiating cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) can vary from <350 s to 500 s among cardiac surgical centers.32 Nevertheless, since other coagulation tests such as the PTT become unclottable with high levels of systemic heparinization, the activated clotting time is the de facto anticoagulation monitor during the conduct of CPB. Anticoagulation guidelines from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists suggest maintaining an activated clotting time >480 s, but acknowledge that “…this minimum threshold value is an approximation and may vary based on the bias of the instrument being used.”33 In cardiac catheterization and electrophysiology laboratories, the activated clotting time is also generally utilized for its rapid results. Interventional cardiology guidelines often quantify the degree of desired anticoagulation by activated clotting time values.34, 35

Like the PTT, the activated clotting time begins by stimulating the intrinsic pathway to form a clot. Also like the PTT, it can be prolonged by antiphospholipid antibodies and hypofibrinogenemia. Because it is a whole blood assay, the activated clotting time is also sensitive to platelet count, hemodilution, and temperature. It is well-known that activated clotting time values diverge from heparin levels during the conduct of CPB,36 leading society guidelines to recommend either monitoring actual heparin levels or re-dosing heparin at fixed intervals during prolonged CPB use.33 One point-of-care system, the Hepcon Hemostasis Management System Plus (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) can provide heparin levels utilizing protamine titration in its “heparin assay” cartridge. The measurement resolution of heparin is 0.4 to 0.7 u/ml depending on the cartridge range, so precision is limited. Assuming the device is used correctly, the Hepcon system generally is within ± 1 u/ml compared to heparin levels measured by anti-Xa assays.37 However, in situations requiring very high levels of heparin such as CPB, which are generally 2–6 u/ml, this limited precision may still alert clinicians to the need for additional heparin when the activated clotting time becomes uninformative due to the above listed factors.38

In addition to heparin, the activated clotting time has been used to monitor bivalirudin for (in order of increasing degree of anticoagulation) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), and cardiac surgery with CPB.39–42 Clinicians should be aware that the linearity of the relationship between activated clotting times and bivalirudin concentration begins to flatten out (i.e. test values change little with increasing doses) at concentrations above 12 μg/ml. This is within the target concentration of 10 – 15 μg/ml for CPB,43 so activated clotting time values above 400 s may reflect bivalirudin concentrations that are almost twice as high as expected. The other parenteral DTI, argatroban, has even less of a linear relationship with the activated clotting time.44 Case reports of argatroban for CPB in cardiac surgery have reported both thrombotic complications as well as catastrophic bleeding using activated clotting time targets of 200 – 400 s.45 Lower levels of argatroban anticoagulation, such as for ECMO, are typically monitored via PTTs versus activated clotting times.46

Viscoelastic Tests

The two major platforms for viscoelastic testing are thromboelastography (TEG, Haemonetics, Boston, MA) and thromboelastometry (ROTEM, Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA). More recently the ClotPro device (Enicor, GMbH, Munich, Germany) which has specific DOAC assays available, and the Quantra analyzer (Hemosonics LLC, Charlottesville, VA), which utilizes soundwaves to detect clotting, have also become available. All viscoelastic testing devices utilize whole blood to measure the time it takes to form a clot, as well as provide information on clot strength and breakdown. There is no “gold standard” for viscoelastic testing, however, and activators and assessment of clotting parameters vary widely. The basic principles, reagents, and measuring methodologies of the various devices have been reviewed elsewhere.47 Viscoelastic testing devices are widely used to diagnose coagulopathy and guide resuscitation with hemostatic blood products,48 but their role in anticoagulation monitoring is less established. While all platforms provide some measure of clot initiation, much like the PTT, the sensitivity for detecting the presence of anticoagulant medication is dependent upon the type and concentration of activator used. Results are therefore not portable across different devices.

The kaolin TEG R and K times are sensitive to the presence of heparin, which has led some investigators to use them to titrate unfractionated heparin in ECMO patients.49, 50 The ROTEM INTEM test, which activates the intrinsic pathway using ellagic acid, has shown correlation with obtained PTT and activated clotting time values, although not with TEG R times, in heparinized ECMO patients.51 The value of adding viscoelastic testing to existing anticoagulation assessment is currently unclear, however. A recent meta-analysis of TEG and ROTEM in ECMO patients concluded that their routine use did not improve bleeding or thrombotic outcomes, although they may improve the detection of surgical bleeding.52

One of the problems is that viscoelastic testing platforms may be too sensitive for heparin titration. Tracings for many anticoagulated patients may simply be a “flat line,” which may not represent the desired anticoagulation level as measured by more conventional tests such as the activated clotting time or PTT.53 Viscoelastic testing devices are much better at detecting the presence of small amounts of residual heparin when heparin reversal is desired. Both TEG and ROTEM offer the addition of heparinase to the standard tests, which has been used to guide administration of additional protamine in cardiac surgery.54–56 Viscoelastic testing devices have not been utilized to guide VKA dosing, but clinicians should be aware that clotting times of both TEG and ROTEM can be prolonged in patients with INR >2.0.57 Dabigatran has a similar effect.58, 59

Monitoring of newer anticoagulants with viscoelastic testing is still an area of active research. The addition of ecarin and thrombin to standard viscoelastic measurements has been explored as a means of assessing levels of parenteral DTIs,60, 61 but these techniques are not yet used clinically. More recently, commercially produced reagents for the ROTEM and TEG 6S platforms have been utilized to provide qualitative assessment of DOAC effects.62, 63 Similarly, the ecarin clotting assay and Russel’s viper venom test have been used on the ClotPro platform to assess plasma concentrations of dabigatran and Xa inhibitors respectively.64, 65 These may eventually allow perioperative physicians to follow reversal of oral DTIs and Xa inhibitors, as doing so with currently available testing options is not recommended.66

Monitoring During Anticoagulation Transitions

Perioperative clinicians are most likely to encounter monitoring difficulties in patients being transitioned from an oral Xa inhibitor or DTI to heparin. While large trials have shown that “bridging therapy” for patients on warfarin or DOACs is not needed prior to elective surgery,67, 68 heparin may still be required either as a primary therapy or prophylaxis for extracorporeal support. The half-life of DOACs ranges from 8 – 14 hours and residual effects may be picked up by laboratory testing even at low drug concentrations. For patients on oral Xa inhibitors, anti-Xa levels for unfractionated heparin monitoring will be additive, leading to supratherapeutic measurements despite subtherapeutic levels of heparin.69 In this particular situation, the PTT may offer better guidance. On the other hand, when transitioning from an oral or parenteral DTI, anti-Xa levels are better indicative of heparin levels than the PTT given the DTI interference in PTT measurements.70 The role of using agents to neutralize DOACs for purposes of laboratory testing is still being explored.71 Guidelines from the International Council for Standardization in Haematology recommend alternative monitoring tests for the first 24 to 36 hours as the patient is being transitioned to unfractionated heparin.2

Residual testing effects of oral anticoagulants also needs to be considered for procedural anticoagulation if activated clotting time monitoring is planned. Although baseline values will be higher, administration of heparin in the presence of VKAs will increase the activated clotting time in a relatively linear manner. This is not necessarily true of DOACs, where most studies have been done in the atrial ablation patients with target activate clotting times of 300 – 350 s.72 While dabigatran behaves similarly to VKAs (i.e. additive), the effects of oral Xa inhibitors, particularly edoxaban, tend to have a blunting effect on the activated clotting time, demonstrating less of an increase for any given amount of heparin administered.73

Conclusions

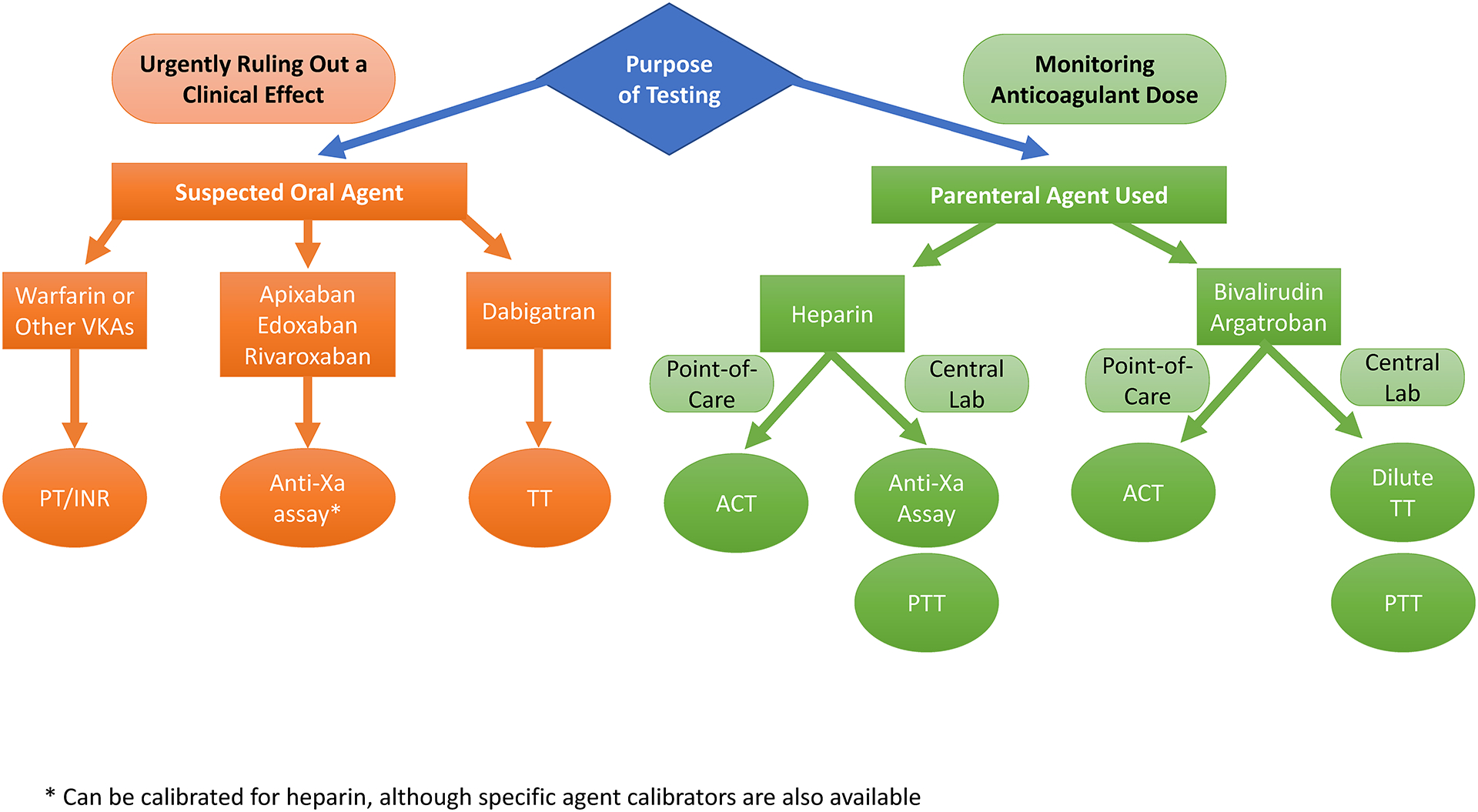

Clinicians encounter anticoagulated patients in all phases of the perioperative period. Whether it is for pre-operative reversal considerations, intraoperative dosing, or post-operative prophylaxis, monitoring the effects of therapy is a requirement. There are more anticoagulants and more testing platforms available today than ever before. Figure 3 represents a basic decision tree of what tests could be appropriate to order based upon anticoagulant and clinical situation. It could easily be adjusted for institution specific assays.

Figure 3: Basic Decision Tree for Anticoagulation Assessment.

For perioperative purposes, the need to obtain anticoagulation assessment is either for urgently ruling out a clinical effect of a patient’s home medication (almost always oral agents) or the need for obtaining a measure of drug level for purposes of dose adjustment (almost always parenteral agents). A normal value of tests in the orange circles effectively rules out clinical effects of the listed agents. Tests in the green circles provide at least a semi-quantitative assessment of how much anticoagulant is present. Table 1 should be referenced for potential confounders. VKAs = vitamin K antagonists, ACT = activated clotting time, PTT – activated partial thromboplastin time, TT = thrombin time, dilute TT = dilute thrombin time.

Newer assays such as the chromogenic anti-Xa level are slowly replacing traditional lab tests such as the PTT, yet even these newer tests have limitations. Even when stopped for surgery, DTIs and Xa inhibitors can influence point-of-care tests such as the activated clotting time, which may have implications for procedural management. Anticoagulants are some of the most dangerous medications prescribed, yet development and widespread availability of tests to monitor their effects in a clinically-relevant timeframe have lagged behind. Additional research on the clinical utility of anticoagulation testing using various lab-based and point-of-care platforms is urgently needed.

Acknowledgements:

Figure 2 was created using biorender.com

Funding:

Support provided by the Emory University School of Medicine. In addition, Dr. Maier is supported by NIH/NHLBI K99 HL150626-01.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Sniecinski has received research funding from OctaPharma, Grifols and Cerus unrelated to this topic. Dr. Maier has no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Cheryl L. Maier, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine.

Roman M. Sniecinski, Department of Anesthesiology, Emory University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Watson RD, Chin BS and Lip GY. Antithrombotic therapy in acute coronary syndromes. BMJ. 2002;325:1348–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosselin RC, Adcock DM and Douxfils J. An update on laboratory assessment for direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Int J Lab Hematol. 2019;41 Suppl 1:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates SM and Weitz JI. Coagulation assays. Circulation. 2005;112:e53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wool GD and Lu CM. Pathology consultation on anticoagulation monitoring: factor X-related assays. American journal of clinical pathology. 2013;140:623–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gehrie E and Laposata M. Test of the month: The chromogenic antifactor Xa assay. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:194–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quick AJ. The coagulation defect in sweet clover disease and in the hemorrhagic chick disease of dietary origin: A consideration of the source of prothromnbin. The American journal of physiology. 1937;118:260. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland LL and Brooks JP. Toward rational fresh frozen plasma transfusion: The effect of plasma transfusion on coagulation test results. American journal of clinical pathology. 2006;126:133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, Dobesh PP, Doherty JU, Eikelboom JW, Florido R, Hucker W, Mehran R, Messe SR, Pollack CV Jr., Rodriguez F, Sarode R, Siegal D and Wiggins BS. 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Management of Bleeding in Patients on Oral Anticoagulants: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;70:3042–3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu D, Gallus A, Hirsh J and Cade J. A prospective study of the value of monitoring heparin treatment with the activated partial thromboplastin time. The New England journal of medicine. 1972;287:324–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandiver JW and Vondracek TG. Antifactor Xa levels versus activated partial thromboplastin time for monitoring unfractionated heparin. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:546–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson JD, Arkin CF, Brandt JT, Cunningham MT, Giles A, Koepke JA and Witte DL. College of American Pathologists Conference XXXI on laboratory monitoring of anticoagulant therapy: laboratory monitoring of unfractionated heparin therapy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:782–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsh J and Raschke R. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:188S–203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Netley J, Roy J, Greenlee J, Hart S, Todt M and Statz B. Bivalirudin Anticoagulation Dosing Protocol for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Retrospective Review. The Journal of extra-corporeal technology. 2018;50:161–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beiderlinden M, Treschan T, Gorlinger K and Peters J. Argatroban in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Artif Organs. 2007;31:461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyer JT, Lind SE, Fisher S, Trujillo TC, Wempe MF and Kiser TH. Evaluation of intravenous direct thrombin inhibitor monitoring tests: Correlation with plasma concentrations and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2020;49:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker P, Platton S, Gibson C, Gray E, Jennings I, Murphy P, Laffan M, British Society for Haematology H and Thrombosis Task F. Guidelines on the laboratory aspects of assays used in haemostasis and thrombosis. British journal of haematology. 2020;191:347–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowak G The ecarin clotting time, a universal method to quantify direct thrombin inhibitors. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33:173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosselin RC and Douxfils J. Ecarin based coagulation testing. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier CL, Asbury WH, Duncan A, Robbins A, Ingle A, Webb A, Stowell SR and Roback JD. Using an old test for new tricks: Measuring direct oral anti-Xa drug levels by conventional heparin-calibrated anti-Xa assay. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:E132–E134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebner M, Birschmann I, Peter A, Hartig F, Spencer C, Kuhn J, Rupp A, Blumenstock G, Zuern CS, Ziemann U and Poli S. Limitations of Specific Coagulation Tests for Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Critical Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy JH, Ageno W, Chan NC, Crowther M, Verhamme P, Weitz JI and Subcommittee on Control of A. When and how to use antidotes for the reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2016;14:623–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdoes G, Martinez Lopez De Arroyabe B, Bolliger D, Ahmed AB, Koster A, Agarwal S, Boer C and von Heymann C. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of direct oral anticoagulants in cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:1535–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart M, Johnson L, Hanigan S, Pipe SW and Li SH. Anti-factor IIa (FIIa) heparin assay for patients on direct factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2020;18:1653–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wool GD. Benefits and Pitfalls of Point-of-Care Coagulation Testing for Anticoagulation Management: An ACLPS Critical Review. American journal of clinical pathology. 2019;151:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karigowda L, Deshpande K, Jones S and Miller J. The accuracy of a point of care measurement of activated partial thromboplastin time in intensive care patients. Pathology. 2019;51:628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooney C, Byrne M, Kapuya P, Pentony L, De la Salle B, Cambridge T, Foley D and British Society for Haematology G. Point of care testing in general haematology. British journal of haematology. 2019;187:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hattersley PG. Activated coagulation time of whole blood. Jama. 1966;196:436–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi Aria M, Erten A and Yalcin O. Technology Advancements in Blood Coagulation Measurements for Point-of-Care Diagnostic Testing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson TZ, Kunak RL, Savage NM, Agarwal S, Chazelle J and Singh G. Intraoperative Monitoring of Heparin: Comparison of Activated Coagulation Time and Whole Blood Heparin Measurements by Different Point-of-Care Devices with Heparin Concentration by Laboratory-Performed Plasma Anti-Xa Assay. Lab Med. 2019;50:348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maslow A, Chambers A, Cheves T and Sweeney J. Assessment of Heparin Anticoagulation Measured Using i-STAT and Hemochron Activated Clotting Time. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2018;32:1603–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welsby IJ, McDonnell E, El-Moalem H, Stafford-Smith M and Toffaletti JG. Activated clotting time systems vary in precision and bias and are not interchangeable when following heparin management protocols during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Clin Monit Comput. 2002;17:287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sniecinski RM, Bennett-Guerrero E and Shore-Lesserson L. Anticoagulation Management and Heparin Resistance During Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Survey of Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Members. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2019;129:e41–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shore-Lesserson L, Baker RA, Ferraris VA, Greilich PE, Fitzgerald D, Roman P and Hammon JW. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and The American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines-Anticoagulation During Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2018;126:413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr., Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW and American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sticherling C, Marin F, Birnie D, Boriani G, Calkins H, Dan GA, Gulizia M, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kuck KH, Moya A, Potpara T, Roldan V, Tilz R and Lip GY. Antithrombotic management in patients undergoing electrophysiological procedures: a European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) position document endorsed by the ESC Working Group Thrombosis, Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), and Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS). Europace. 2015;17:1197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Despotis GJ, Summerfield AL, Joist JH, Goodnough LT, Santoro SA, Spitznagel E, Cox JL and Lappas DG. Comparison of activated coagulation time and whole blood heparin measurements with laboratory plasma anti-Xa heparin concentration in patients having cardiac operations. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1994;108:1076–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raymond PD, Ray MJ, Callen SN and Marsh NA. Heparin monitoring during cardiac surgery. Part 1: Validation of whole-blood heparin concentration and activated clotting time. Perfusion. 2003;18:269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koster A, Fischer T, Praus M, Haberzettl H, Kuebler WM, Hetzer R and Kuppe H. Hemostatic activation and inflammatory response during cardiopulmonary bypass: impact of heparin management. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dyke CM, Smedira NG, Koster A, Aronson S, McCarthy HL 2nd, Kirshner R, Lincoff AM and Spiess BD. A comparison of bivalirudin to heparin with protamine reversal in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: the EVOLUTION-ON study. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2006;131:533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koster A, Dyke CM, Aldea G, Smedira NG, McCarthy HL 2nd, Aronson S, Hetzer R, Avery E, Spiess B and Lincoff AM. Bivalirudin during cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with previous or acute heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and heparin antibodies: results of the CHOOSE-ON trial. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2007;83:572–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanfilippo F, Asmussen S, Maybauer DM, Santonocito C, Fraser JF, Erdoes G and Maybauer MO. Bivalirudin for Alternative Anticoagulation in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhogal S, Mukherjee D, Bagai J, Truong HT, Panchal HB, Murtaza G, Zaman M, Sachdeva R and Paul TK. Bivalirudin Versus Heparin During Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2020;20:3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zucker ML, Koster A, Prats J and Laduca FM. Sensitivity of a modified ACT test to levels of bivalirudin used during cardiac surgery. The Journal of extra-corporeal technology. 2005;37:364–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akimoto K, Klinkhardt U, Zeiher A, Niethammer M and Harder S. Anticoagulation with argatroban for elective percutaneous coronary intervention: population pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of coagulation parameters. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:805–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koster A, Faraoni D and Levy JH. Argatroban and Bivalirudin for Perioperative Anticoagulation in Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geli J, Capoccia M, Maybauer DM and Maybauer MO. Argatroban Anticoagulation for Adult Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med. 2021:885066621993739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carll T and Wool GD. Basic principles of viscoelastic testing. Transfusion. 2020;60 Suppl 6:S1–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raphael J, Mazer CD, Subramani S, Schroeder A, Abdalla M, Ferreira R, Roman PE, Patel N, Welsby I, Greilich PE, Harvey R, Ranucci M, Heller LB, Boer C, Wilkey A, Hill SE, Nuttall GA, Palvadi RR, Patel PA, Wilkey B, Gaitan B, Hill SS, Kwak J, Klick J, Bollen BA, Shore-Lesserson L, Abernathy J, Schwann N and Lau WT. Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Clinical Practice Improvement Advisory for Management of Perioperative Bleeding and Hemostasis in Cardiac Surgery Patients. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2019;129:1209–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colman E, Yin EB, Laine G, Chatterjee S, Saatee S, Herlihy JP, Reyes MA and Bracey AW. Evaluation of a heparin monitoring protocol for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3325–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panigada M, G EI, Brioni M, Panarello G, Protti A, Grasselli G, Occhipinti G, Novembrino C, Consonni D, Arcadipane A, Gattinoni L and Pesenti A. Thromboelastography-based anticoagulation management during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a safety and feasibility pilot study. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giani M, Russotto V, Pozzi M, Forlini C, Fornasari C, Villa S, Avalli L, Rona R and Foti G. Thromboelastometry, Thromboelastography, and Conventional Tests to Assess Anticoagulation During Extracorporeal Support: A Prospective Observational Study. ASAIO J. 2021;67:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiritano F, Fina D, Lorusso R, Ten Cate H, Kowalewski M, Matteucci M, Serra R, Mastroroberto P and Serraino GF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of point-of-care testing for anticoagulation management during ECMO. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2021;73:110330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Panigada M, Iapichino G, L’Acqua C, Protti A, Cressoni M, Consonni D, Mietto C and Gattinoni L. Prevalence of “Flat-Line” Thromboelastography During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Respiratory Failure in Adults. ASAIO J. 2016;62:302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galeone A, Rotunno C, Guida P, Bisceglie A, Rubino G, Schinosa Lde L and Paparella D. Monitoring incomplete heparin reversal and heparin rebound after cardiac surgery. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2013;27:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levin AI, Heine AM, Coetzee JF and Coetzee A. Heparinase thromboelastography compared with activated coagulation time for protamine titration after cardiopulmonary bypass. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2014;28:224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mittermayr M, Velik-Salchner C, Stalzer B, Margreiter J, Klingler A, Streif W, Fries D and Innerhofer P. Detection of protamine and heparin after termination of cardiopulmonary bypass by thrombelastometry (ROTEM): results of a pilot study. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009;108:743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidt DE, Holmstrom M, Majeed A, Naslin D, Wallen H and Agren A. Detection of elevated INR by thromboelastometry and thromboelastography in warfarin treated patients and healthy controls. Thrombosis research. 2015;135:1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solbeck S, Jensen AS, Maschmann C, Stensballe J, Ostrowski SR and Johansson PI. The anticoagulant effect of therapeutic levels of dabigatran in atrial fibrillation evaluated by thrombelastography (TEG((R))), Hemoclot Thrombin Inhibitor (HTI) assay and Ecarin Clotting Time (ECT). Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2018;78:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sokol J, Nehaj F, Ivankova J, Mokan M, Zolkova J, Lisa L, Linekova L, Mokan M and Stasko J. Impact of Dabigatran Treatment on Rotation Thromboelastometry. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2021;27:1076029620983902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taketomi T, Szlam F, Vinten-Johansen J, Levy JH and Tanaka KA. Thrombin-activated thrombelastography for evaluation of thrombin interaction with thrombin inhibitors. Blood coagulation & fibrinolysis : an international journal in haemostasis and thrombosis. 2007;18:761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koster A, Buz S, Krabatsch T, Dehmel F, Hetzer R, Kuppe H and Dyke C. Monitoring of bivalirudin anticoagulation during and after cardiopulmonary bypass using an ecarin-activated TEG system. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2008;23:321–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vedovati MC, Mosconi MG, Isidori F, Agnelli G and Becattini C. Global thromboelastometry in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants: the RO-DOA study. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2020;49:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Myers SP, Dyer MR, Hassoune A, Brown JB, Sperry JL, Meyer MP, Rosengart MR and Neal MD. Correlation of Thromboelastography with Apparent Rivaroxaban Concentration: Has Point-of-Care Testing Improved? Anesthesiology. 2020;132:280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groene P, Wagner D, Kammerer T, Kellert L, Giebl A, Massberg S and Schafer ST. Viscoelastometry for detecting oral anticoagulants. Thromb J. 2021;19:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oberladstatter D, Voelckel W, Schlimp C, Zipperle J, Ziegler B, Grottke O and Schochl H. A prospective observational study of the rapid detection of clinically-relevant plasma direct oral anticoagulant levels following acute traumatic injury. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Douxfils J, Adcock D, Bates SM, Favaloro EJ, Gouin-Thibault I, Guillermo C, Kawai Y, Lindhoff-Last PDE, Kitchen S and Gosselin RC. 2021 Update of the International Council for Standardization in Haematology Recommendations for Laboratory Measurement of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, Becker RC, Caprini JA, Dunn AS, Garcia DA, Jacobson A, Jaffer AK, Kong DF, Schulman S, Turpie AG, Hasselblad V, Ortel TL and Investigators B. Perioperative Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373:823–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Duncan J, Carrier M, Le Gal G, Tafur AJ, Vanassche T, Verhamme P, Shivakumar S, Gross PL, Lee AYY, Yeo E, Solymoss S, Kassis J, Le Templier G, Kowalski S, Blostein M, Shah V, MacKay E, Wu C, Clark NP, Bates SM, Spencer FA, Arnaoutoglou E, Coppens M, Arnold DM, Caprini JA, Li N, Moffat KA, Syed S and Schulman S. Perioperative Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Receiving a Direct Oral Anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1469–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ahuja T, Yang I, Huynh Q, Papadopoulos J and Green D. Perils of Antithrombotic Transitions: Effect of Oral Factor Xa Inhibitors on the Heparin Antifactor Xa Assay. Ther Drug Monit. 2020;42:737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adcock DM, Gosselin R, Kitchen S and Dwyre DM. The effect of dabigatran on select specialty coagulation assays. American journal of clinical pathology. 2013;139:102–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Platton S and Hunt C. Influence of DOAC Stop on coagulation assays in samples from patients on rivaroxaban or apixaban. Int J Lab Hematol. 2019;41:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin AC, Godier A, Narayanan K, Smadja DM and Marijon E. Management of Intraprocedural Anticoagulation in Patients on Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants Undergoing Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Understanding the Gaps in Evidence. Circulation. 2018;138:627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sairaku A, Morishima N, Matsumura H, Amioka M, Maeda J, Watanabe Y and Nakano Y. Intraprocedural anticoagulation and post-procedural hemoglobin fall in atrial fibrillation ablation with minimally interrupted direct oral anticoagulants: comparisons across 4 drugs. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]