Abstract

Background:

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the brain and face present unique challenges for clinicians. Cerebral AVMs may induce hemorrhage or form aneurysms, while facial AVMs can cause significant disfigurement and pain. Moreover, facial AVMs often draw blood supply from arteries providing critical blood flow to other important structures of the head which may make them impossible to treat curatively. Medical adjuvants may be an important consideration in the management of these patients.

Summary:

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify other instances of molecular target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors used as medical adjuvants for the treatment of cranial and facial AVMs. We also present 2 cases from our own institution where patients were treated with partial embolization, followed by adjuvant therapy with rapamycin. After screening a total of 75 articles, 7 were identified which described use of rapamycin in the treatment of inoperable cranial or facial AVM. In total, 21 cases were reviewed. The median treatment duration was 12 months (3–24.5 months), and the highest recorded dose was 3.5 mg/m2. 76.2% of patients demonstrated at least a partial response to rapamycin therapy. In 2 patients treated at our institution, symptomatic and radiographic improvement were noted 6 months after initiation of therapy.

Key Messages:

Early results have been encouraging in a small number of patients with inoperable AVM of the head and face treated with mTOR inhibitors. Further study of medical adjuvants such as rapamycin may be worthwhile.

Keywords: Molecular target of rapamycin, Arteriovenous malformation, Rapamycin, Embolization, Adjuvant, Medical therapy, Vascular malformation, Surgery, Bleeding, Inoperable

Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are a class of vascular anomalies characterized by a direct interface between arterial and venous blood supplies without an intervening capillary bed. AVMs are composed of 3 vascular structures: an aggregation of anomalous vessels (nidus), feeding artery or arteries, and a draining vein or veins [1]. While AVMs can occur in any organ, brain AVMs present unique challenges due to their tendency to induce hemorrhage, aneurysms, and venous ectasia [2]. Cutaneous AVMs have also been described in the literature and patients typically present with disfigurement, pain, bleeding, and may experience complications such as thrombosis and organ dysfunction [3].

The current gold-standard treatment for brain AVMs involves microsurgical obliteration [4]. Other strategies, including embolization and radiosurgery, have yielded successful outcomes in appropriately selected cases [5]. Treatment of some AVMs, however, presents an unacceptable level of risk. This is particularly true of those which are deep, near critical structures, or too large [6]. Furthermore, some large-scale studies have demonstrated that partial embolization can increase annual bleeding rates [7], perhaps by increasing blood flow through the remaining blood supply. Additionally, if partially treated, an AVM may also recruit new supplying arteries.

While partial treatment of AVMs does not decrease risk of hemorrhage, some patients may still improve symptomatically from a reduction in shunted blood flow [24]. These patients present a significant challenge for clinicians, as they frequently require repeated embolizations over the course of their lifetime, sometimes multiple times per year. Given limitations of surgical and interventional techniques, there may be an important role for medical adjuvants in these cases.

Rapamycin, an inhibitor of the molecular target of rapamycin (mTOR), has been successfully implicated in the treatment of vascular diseases and has been shown to successfully treat lymphatic malformations, a related class of circulatory anomalies [8, 9, 23]. mTOR is a serine-threonine kinase that is a critical regulator of cellular proliferation and survival. Rapamycin exerts its effects by forming a complex with intracellular FK binding proteins (FKBP, specifically FKBP12), which directly inhibits mTOR, arresting the cell cycle at the G1 phase and halting blood vessel formation [9, 10]. Treatment of AVM has been proposed as an off-label use of rapamycin given its mechanism of action and the potential for disrupting AVM pathophysiology. Furthermore, early results have been encouraging with treatment of pediatric AVMs of the head and face [3, 6]. In this article, we discuss 2 cases of patients recently treated at our institution with rapamycin and review available literature regarding medical therapy for inoperable AVM.

Methods

Literature Review

The study was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. We performed a systematic search of electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar, up to August 2020. Keywords used in combination or individually were “arteriovenous malformation,” “AVM,” “coiling,” “facial,” “cranial,” “Rapamycin,” and “rapamycin,” using Boolean operators “OR” and “AND.” Search was also performed using “NOT”: “coronary,” “flow-diverting,” and “pipeline.” Articles identified in database search were then screened by title and abstract for eligibility. Those which passed screening were then downloaded and assessed against our inclusion criteria. Articles were reviewed by 3 authors independently, and articles were included by consensus. Further literature was examined by searching the reference lists of included studies.

Original research studies, case series, and case reports on patients placed on medical therapy for cranial or facial AVM were included. Exclusion criteria applied to studies containing only patients with AVMs in other parts of the body not including the head or face and studies on animals. Studies published in abstract form only, review articles, meta-analysis, guidelines, or lacking information on medications used were also excluded.

Treatments

Two patients with inoperable AVM of the head and face were treated at our institution after institutional review and approval (IRB #20190857). Our rapamycin protocol is as follows: when possible, patients initiate treatment 14–18 days prior to embolization, receiving 2 mg per day. Rapamycin concentrations are measured between days 4 and 7, following the initial rapamycin administration dosage. If rapamycin trough concentrations are low, then a loading dose may be considered in addition to the new maintenance dose. The loading dose is determined using the formula: Rapamycin loading dose = 3 × (new maintenance dose − current dose). Rapamycin trough concentrations were maintained within the therapeutic range of 3–20 ng/mL, and total treatment lasted 14–18 days.

Review of Literature

We identified 75 articles in our initial database search. All 75 records were screened, and 11 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Four articles were subsequently excluded. In 3 articles, the lesion site could not be identified, and one study was conducted in animals. We identified 7 studies that detailed treatment of head and face AVMs using rapamycin. From these studies, 21 patients were treated. The median treatment duration was 12 months (3–24.5 months), and the highest recorded dose was 3.5 mg/m2. With regard to efficacy, 76.2% of previously treated AVM patients demonstrated at least a partial response to rapamycin therapy. A summary of previous reports on rapamycin use in cranial and facial AVM management is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of previous reports detailing the use of rapamycin in cranial or facial AVMs

| Author | Objective | Dose | Methods | Response measure | Patients with facial or cranial lesions, n | Duration of treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodds et al. [12] | Efficacy and tolerability of topical formulations of rapamycin in the treatment of various simple and combined vascular malformations and tumors | Topical rapamycin (17 used 1% rapamycin, 1 used 3% rapamycin) | Eighteen patients with any vascular anomaly treated exclusively with topical rapamycin were retrospectively reviewed | Response measured as therapeutic benefit in reduction of bleeding, infection, induration/thickness, blebs and exudate, pain, cosmesis, and functional impairment Clinicians rated therapeutic benefit as follows: 0% (none), 1–25% (minimal), 26–50% (moderate), or >50% (marked) improvement |

1 patient with facial lesion | 11 months | >50% reduction in induration/thickness |

| Hammer et al. [14] | To assess the efficacy and safety of this treatment in patients with extensive or complex slow-flow vascular malformations | 2 mg/day (adults, children over 12) 0.8 mg/m2/twice a day (children under 12) | Rapamycin was administered orally on a continuous dosing schedule | Response measured as follows: Complete resolution: complete disappearance of lesion or normalization of life quality Partial response: reduction of ≥20% in size of the vascular lesion, improvement of symptoms, or life quality Absence of response: Disease progression, disease stability, no improvement of symptoms, or life quality |

4 patients with cranial or facial lesions | Average duration of 19 months for the 4 patients | 1 patient was not evaluable, remaining 3 demonstrated functional improvement |

| Gabeff et al. [13] | To evaluate efficacy of rapamycin in a series of 10 patients | 0.6–3.5 mg/m2 | Retrospective analysis of patients treated with rapamycin | Response measured as follows Complete response: >90% decrease in AVM volume on clinical and imaging assessments Partial response: >25% decrease in AVM volume and/or healing of hemorrhage and necrosis No response: stabilization, <25% decrease in AVM volume or worsening |

5 patients with facial AVM | Median treatment time was 24.5 months | 2 patients nonresponsive, patients with partial response |

| Maynard et al. [6] | Case report on pediatric patient with thalamic AVM | 0.8 mg/m2 | Patient started on 1-year trial of rapamycin | Response defined as reduction in AVM volume on MRI and reduction in clinical symptoms (e.g., TIA frequency) | 1 patient with cranial AVM | 1 year | Patient currently responding well to treatment, >50% reduction in TIA frequency |

| Sandbank et al. [15] | 19 patients treated with rapamycin for complicated vascular anomalies | Oral 0.6 mg/m2 rapamycin twice daily (17 patients) or twice daily application of 0.2% rapamycin gel (2 patients) | 19 patients treated with rapamycin | Response measured as follows: Positive response: clinical/radiological stabilization or a decrease in lesion size, overgrowth, decreased thrombosis or cellulitis, improved life quality, or reduction in impairment or pain Partial response: improvement in the symptoms and a reduction in the lesion, but a persistence of the anomaly Complete response: resolution of symptoms and lesion |

1 patient with cervicofacial lesion | 3 months | Patient demonstrated partial response, reduction in lesion size |

| Triana et al. [16] | Retrospective review of 41 patients treated with rapamycin for vascular lesions | 0.8 mg/m2/12 h | 41 patients treated with rapamycin | Partial response: improvement of symptoms and reduction of the lesion, but persistence of the anomaly Complete response: disappearance of symptoms and lesion, without visualization of the anomaly by imaging |

6 patients with cranial, facial, or cervicofacial lesions | 8.5 months | Two patients did not respond to treatment, 4 patients did respond to treatment |

| Chelliah et al. [11] | Retrospective review of 6 patients treated with rapamycin | 10–15 ng/mL target blood concentration | 6 patients treated with rapamycin | Response: outcomes listed as decrease in AVM volume, resolution of pain and impairment, or bleeding. Measured on a case-by-case basis | 3 patients with facial lesions | 19 months | All 3 patients at least partially responded to rapamycin therapy |

AVMs, arteriovenous malformations; TIA, transient ischemic attack; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

mTOR inhibitors are recently used alternatives to surgical management of large, superficial AVMs in the pediatric population, with rapamycin being the drug of choice in many published reports [3, 6]. To date, our study details the 22nd and 23rd known patients to be treated with an mTOR inhibitor for management of a cranial or facial AVM [6, 11–16]. There has been substantial variability in dosing and treatment duration across institutions, with treatment duration ranging from 3 to 24.5 months, with a median treatment duration of 12 months across all reported cases [17, 18]. With respect to dosage, all but 3 institutions dosed topical rapamycin treatment by surface area of administration, with the upper dosage limit being 3.5 mg/m2 [17].

Determination of rapamycin response in the current literature is highly variable, with a mixture of parameters (reduction in lesion size, pain alleviation, bleeding episodes, etc.) being used to determine if a patient is nonresponsive, partially responsive, or fully responsive to rapamycin treatment [6, 15–19]. However, despite parameter variability, 16 of the 21 (76.2%) previously described patients in the literature demonstrated a favorable response to treatment. This promising level of efficacy is contrary to a recent systematic review of rapamycin usage in vascular malformations, which demonstrated only a low-level of evidence supporting rapamycin efficacy [17].

To date, there are only 2 randomized controlled trials investigating the role of mTOR inhibitors in vascular malformations, and none demonstrating the utility of rapamycin in AVMs of the brain or face. Moreover, these trials demonstrated conflicting results: one found topical rapamycin effective in treatment of port-wine stains and Sturge-Weber syndrome and the other found topical rapamycin ineffective [18, 19]. Patients in our study were treated with a maximum dose of 40 mg rapamycin to achieve an optimum level of 3–20 ng/mL. However, further research is required to determine the efficacy, optimal dosage, and optimal treatment duration of rapamycin. One earlier study suggested rapamycin promoted coagulopathy in patients treated with low-flow AVMs based on correlation with significant decrease in D-dimer levels [25]. However, in a case series of both pediatric and adult patients, it was noted that children developed oral ulcers and oral mucositis following rapamycin treatment for extracranial AVMs [13]. Other authors also reported relatively infrequent and minor complications, such as transient hyperlipidemia and minor opportunistic infection [16]. Randomized controlled trials investigating both the safety profile and efficacy of rapamycin in AVM management would be helpful in this regard.

Other proposed medical treatments for AVMs focus on the disruption of the vascular endothelial growth factor and KRAS-mitogen activated protein kinase-extracellular signal regulated kinase pathway, which have been implicated in AVM formation [1, 20]. MEK inhibitors have been effective in treating AVM based on case reports, but may not be as effective as mTOR inhibitors because they accelerate angiogenesis through parallel stimulation of the mTOR pathway [6].

Other steps in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PIK-3)/protein kinase B/mTOR pathway, which promotes vascular maturation and stability, may offer other opportunities for targeted therapy [14]. The PIK-3/protein kinase B/mTOR pathway is mediated by the tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2 and its ligands, angiopoietin-1, and angiopoietin-2 [9]. TIE2 mutations have been demonstrated in over half of all venous malformations [21]. A number of clinical trials evaluating the use of dactolisib, a dual PIK-3/mTOR inhibitor, are ongoing in treatment of various cancers [22].

Case Presentation

Case #1

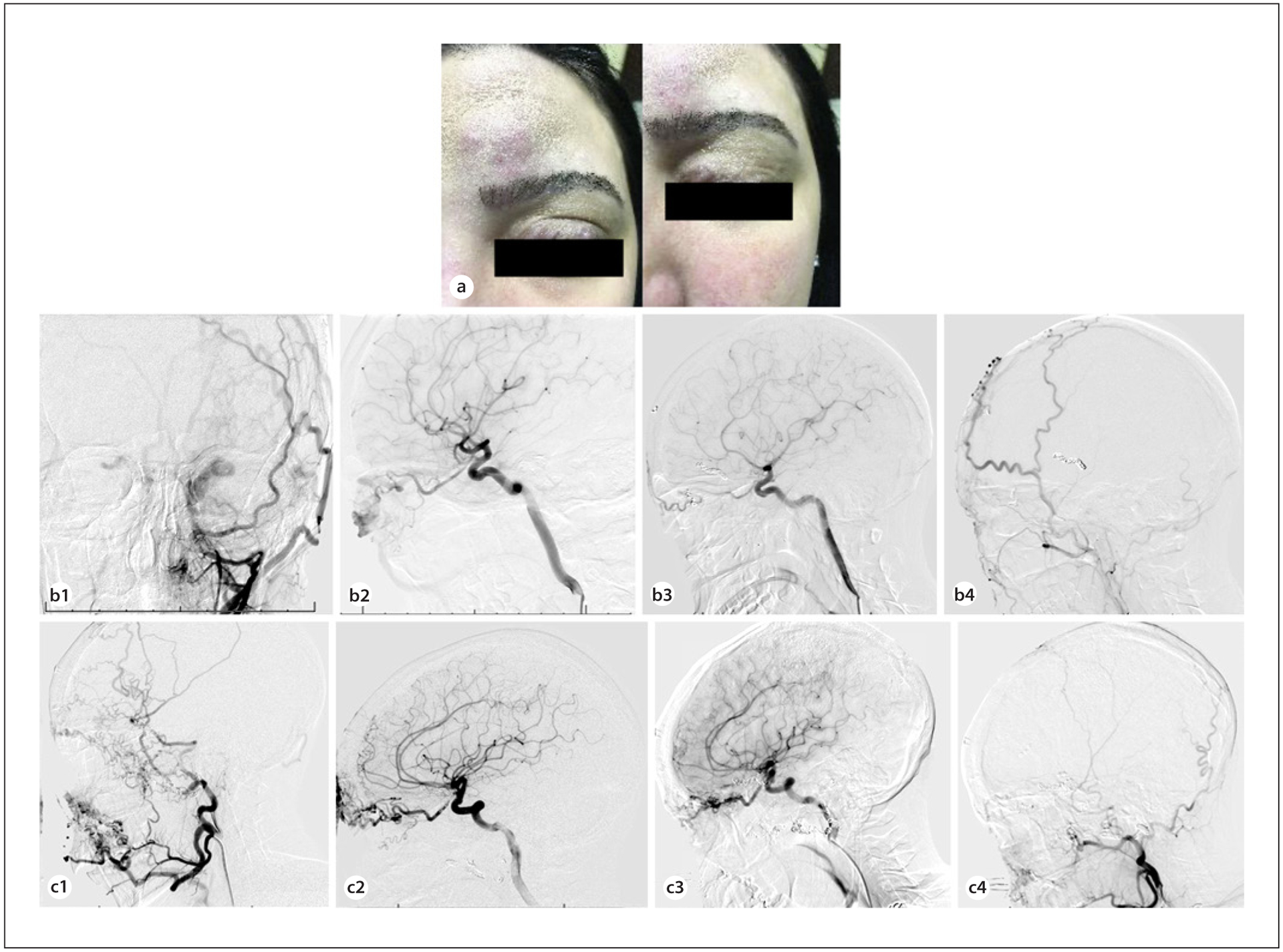

A 23-years-old woman developed a left orbital-facial AVM which caused pain, difficulty with eye opening, and cosmetic worsening secondary to swelling and difficulty opening the eye (Fig. 1a). The malformation was fed by the left facial artery, left superior temporal artery, and left ophthalmic artery distal to the central retinal artery and included a prenidal fusiform aneurysm of the left ophthalmic artery distal to the origin of the central retinal artery. Venous drainage was via the superior ophthalmic veins, cavernous sinus, pterygopalatine fossa, and facial vein. The patient had seen ENT and plastic surgery teams but declined surgery out of concern for cosmetic disfiguration, opting for palliative embolization instead.

Fig. 1.

a A 23-year-old woman presented with difficulty opening her eye, pain, and swelling secondary to a left orbito-facial AVM. Curative surgery in this case would have involved extensive soft tissue dissection, and the patient wished to avoid undesirable cosmetic defects from open surgery. b The malformation prior to embolization was fed by branches of the facial and superficial temporal arteries as seen on anteroposterior projection of left external carotid injection (b1). Lateral projected view of internal carotid injection shows blood supply from the ophthalmic artery (b2). At 6-month follow-up after embolization and therapy with rapamycin, minimal residual contrast is visualized within the AVM on AP (b3) and lateral (b4) angiography of the external and internal carotid, respectively. c A 28-year-old woman with a right facial-orbital AVM presented with refractory epistaxis and left-sided retro-orbital pressure. She had previously undergone multiple operations, including enucleation of the right eye. The AVM was supplied by feeders arising from the internal maxillary, lingual, and superficial temporal arteries, as shown in the lateral external carotid injection (c1), and by the ophthalmic artery as shown in the lateral internal carotid injection (c2). In staged sessions, feeding pedicles including branches of the ophthalmic and sphenopalatine arteries were embolized and coiling of the ophthalmic artery aneurysm were performed. The patient subsequently initiated therapy with rapamycin. At 1-year follow-up, there was no significant increase in residual filling at the mandible from the facial and lingual arteries and the inferolateral trunk compared to what was seen following embolization (lateral projection of internal carotid injection (c3); lateral projection of external carotid injection (c4)). Epistaxis was noted to have ceased completely. AVM, arteriovenous malformation.

The distal ophthalmic artery aneurysm was coiled, and pedicles arising from the left facial artery, internal maxillary artery, and superficial temporal artery were embolized (Fig. 1b). Following embolization, there was a noted decrease in preoperative swelling over the patient’s forehead and left eyelid. Postoperatively, the patient was placed on rapamycin 2 mg daily by mouth, adjusted for serum trough 5–15 ng/mL. At the 6-month angiogram, there remained minimum flow into the AVM, and swelling over the brow and eyelid had subsided completely.

Case #2

A 28-years-old woman with a longstanding facial-orbital AVM having previously undergone partial resection and right eye enucleation complicated by poor wound healing, presented to the emergency room with refractory epistaxis and retro-orbital pressure on the left. She had also previously undergone over 10 palliative embolization procedures at another hospital. Our institution’s ENT team initially performed endonasal cauterization of bleeding sphenopalatine and ethmoidal arteries. The patient continued to have more than 3 episodes of epistaxis every month. Next, in 2 staged sessions, feeding pedicles including branches of the ophthalmic and sphenopalatine arteries were embolized and coiling of an ophthalmic artery aneurysm were performed (Fig. 1c). The patient continued to have epistaxis episodes every or every other month. The patient was then placed on rapamycin following intervention using our standard protocol.

Six months later, she underwent another combined plastic/ENT surgery for excision of other branches affecting the forehead and cheek, as well as laser cauterization of septal telangiectasias. She was noted to have minimal bleeding at the time of that operation. The patient was seen again at 1-year follow-up and was found to have an overall marked decrease in the size of the AVM, with small residual filling at the mandible from the facial and lingual arteries and the inferolateral trunk. Epistaxis is noted to have ceased completely, and she currently has no other AVM-related symptoms. Retro-orbital pressure had resolved and along with daily headaches.

Conclusion

Early results of treatment of inoperable AVMs of the head and face with medications that target molecular pathways in AVM development have been encouraging. We present 2 cases where adjuvant therapy with rapamycin prevented repeat intervention and review the literature surrounding rapamycin treatment in AVMs. Further studies regarding the efficacy of mTOR inhibitors for cranial and facial lesions may be worthwhile.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the University of Miami for its support of the authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

R.M.S. research is supported by the NREF, Joe Niekro Foundation, Brain Aneurysm Foundation, Bee Foundation, and National Institute of Health (R01NS111119-01A1) and (UL1TR002736, KL2TR002737) through the Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. R.M.S. has consulting agreements with Penumbra, Abbott, Medtronic, InNeuroCo, and Cerenovus. J.W.T. research is supported by the Brain Aneurysm Foundation and the Aneurysm and AVM Foundation.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

This research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from the patients for publication of this case report and any images.

References

- 1.Thomas JM, Surendran S, Abraham M, Rajavelu A, Kartha CC. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in the development of arteriovenous malformations in the brain. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peschillo S, Caporlingua A, Colonnese C, Guidetti G. Brain AVMs: an endovascular, surgical, and radiosurgical update. Scientific-WorldJournal. 2014;2014:834931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams DM, Ricci KW. Vascular anomalies: diagnosis of complicated anomalies and new medical treatment options. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:455–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendok BR, El Tecle NE, El Ahmadieh TY, Koht A, Gallagher TA, Carroll TJ, et al. Advances and innovations in brain arteriovenous malformation surgery. Neurosurgery. 2014;74(Suppl 1):S60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CJ, Norat P, Ding D, Mendes GAC, Tvrdik P, Park MS, et al. Transvenous embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations: a review of techniques, indications, and outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;45:E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maynard K, LoPresti M, Iacobas I, Kan P, Lam S. Antiangiogenic agent as a novel treatment for pediatric intracranial arteriovenous malformations: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blauwblomme T, Bourgeois M, Meyer P, Puget S, Di Rocco F, Boddaert N, et al. Long-term outcome of 106 consecutive pediatric ruptured brain arteriovenous malformations after combined treatment. Stroke. 2014;45:1664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goncharova EA. mTOR and vascular remodeling in lung diseases: current challenges and therapeutic prospects. FASEB J. 2013;27:1796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Switon K, Kotulska K, Janusz-Kaminska A, Zmorzynska J, Jaworski J. Molecular neurobiology of mTOR. Neuroscience. 2017;341:112–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehgal SN. Rapamycin: its discovery, biological properties, and mechanism of action. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:7s–14s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chelliah MP, Do HM, Zinn Z, Patel V, Jeng M, Khosla RK, et al. Management of complex arteriovenous malformations using a novel combination therapeutic algorithm. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1316–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodds M, Tollefson M, Castelo-Soccio L, Garzon MC, Hogeling M, Hook K, et al. Treatment of superficial vascular anomalies with topical rapamycin: a multicenter case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37: 272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabeff R, Boccara O, Soupre V, Lorette G, Bodemer C, Herbreteau D, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of rapamycin (rapamycin) for extracranial arteriovenous malformations in children and adults. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammer J, Seront E, Duez S, Dupont S, Van Damme A, Schmitz S, et al. Rapamycin is efficacious in treatment for extensive and/or complex slow-flow vascular malformations: a monocentric prospective phase ii study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandbank S, Molho-Pessach V, Farkas A, Barzilai A, Greenberger S. Oral and topical rapamycin for vascular anomalies: a multicentre study and review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:990–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Triana P, Dore M, Cerezo VN, Cervantes M, Sánchez AV, Ferrero MM, et al. Rapamycin in the treatment of vascular anomalies. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2017;27:86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freixo C, Ferreira V, Martins J, Almeida R, Caldeira D, Rosa M, et al. Efficacy and safety of rapamycin in the treatment of vascular anomalies: a systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greveling K, Prens EP, van Doorn MB. Treatment of port wine stains using pulsed dye laser, erbium yag laser, and topical rapamycin (rapamycin): a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marqués L, Núñez-Córdoba JM, Aguado L, Pretel M, Boixeda P, Nagore E, et al. Topical rapamycin combined with pulsed dye laser in the treatment of capillary vascular malformations in sturge-weber syndrome: phase II, randomized, double-blind, intraindividual placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:151–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolaev S, Vetiska S, Bonilla X, Boudreau E, Jauhiainen S, Rezai Jahromi B. Somatic activating KRAS mutations in arteriovenous malformations of the brain. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:250–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soblet J, Limaye N, Uebelhoer M, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Variable somatic TIE2 mutations in half of sporadic venous malformations. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4:179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Nie J, Ma X, Wei Y, Peng Y, Wei X. Targeting pi3k in cancer: mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waner M, O TM. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of lymphatic malformations of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:159–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suazo L, Foerster B, Fermin R, Speckter H, Vilchez C, Oviedo J, et al. Measurement of blood flow in arteriovenous malformations before and after embolization using arterial spin labeling. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18: 42–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mack JM, Verkamp B, Richter GT, Nicholas R, Stewart K, Crary SE. Effect of sirolimus on coagulopathy of slow-flow vascular malformations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019October; 66(10):e27896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]