Abstract

Background:

Better understanding of patients’ and their family members’ experiences of delirium and related distress during critical care is required to inform the development of targeted nonpharmacologic interventions.

Objective:

To examine and synthesize qualitative data on patients’ and their family members’ delirium experiences and relieving factors in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Design:

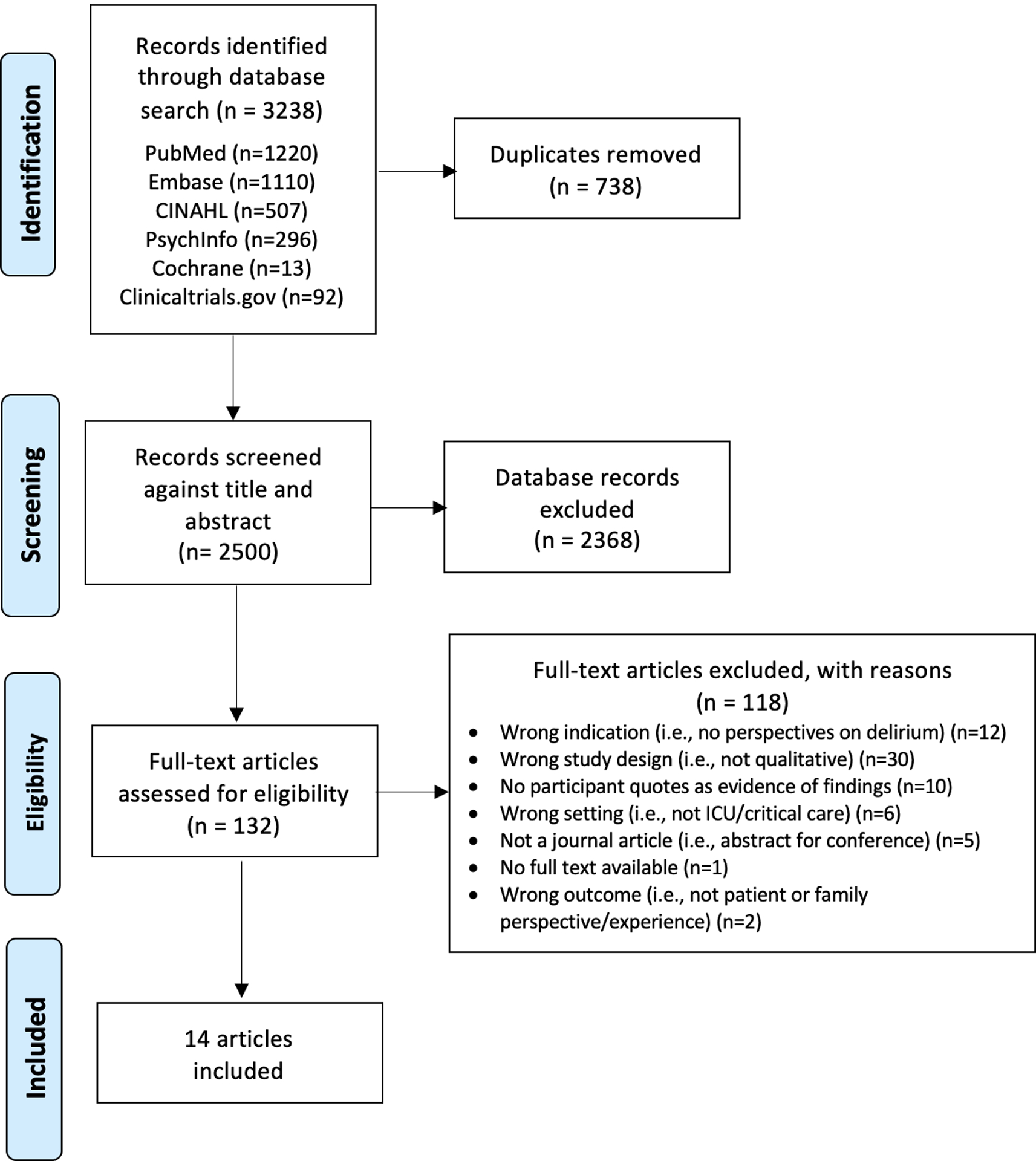

We conducted a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Eligible studies contained adult patient or family quotes about delirium during critical care, published in English in a peer-reviewed journal since 1980. Data sources included PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane and Clinicaltrials.gov.

Methods:

Systematic searches yielded 3238 identified articles, of which 14 reporting 13 studies were included. Two reviewers independently extracted data into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Qualitative meta-synthesis was performed through line-by-line coding of relevant quotes, organisation of codes into descriptive themes, and development of analytical themes. Five patients/family members with experience of ICU delirium contributed to the thematic analysis.

Results:

Qualitative meta-synthesis resulted in four major themes and two sub-themes. Key new patient and family-centric insights regarding delirium-related distress in the ICU included articulation of the distinct emotions experienced during and after delirium (for patients, predominantly fear, anger and shame); its ‘whole-person’ nature; and the value that patients and family members placed on clinicians’ compassion, communication, and connectedness.

Conclusions:

Distinct difficult emotions and other forms of distress are experienced by patients and families during ICU delirium, during which patients and family members highly value human kindness and empathy. Future studies should further explore and address the many facets of delirium-related distress during critical care using these insights and include patient-reported measures of the predominant difficult emotions.

Key terms: Caregiver support, Critical care, Nursing, Delirium, Stress, Psychological, Qualitative studies, Systematic review, Meta synthesis

1. INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a serious and acute neurocognitive disorder that is a frequent source of suffering for critically ill patients and their families (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Brummel et al., 2014; Devlin et al., 2018; Krewulak et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2020). Despite growing knowledge of delirium epidemiology, prevention, and treatment, it remains uncertain how such distress is best responded to (Devlin et al., 2018). Antipsychotics and benzodiazepines are often used to manage delirium-related symptoms (e.g., agitation) (Mac Sweeney et al., 2010, Morandi et al., 2017, Patel et al., 2009, Selim and Ely, 2017). However, patient and family member distress may require a different management approach. Yet the limited measurement of psychological outcomes in ICU delirium research means there is a knowledge gap about the best management approaches (Devlin et al., 2018).

Reasons for the under-measurement of psychological outcomes in delirium research include definitional ambiguities for delirium-related distress, a lack of established measures for the subjective experience of delirium, and a decreased ability to communicate during delirium) (Williams et al., 2020). Efforts are now being made to articulate the nature of delirium-related distress. Emotional dysregulation characterized by irritability, anger, fear, anxiety, and perplexity, has been presented as a domain of delirium (Maldonado, 2018). However, the definition of emotional dysregulation varies (D’Agostino et al., 2016), and it is not diagnostic for delirium (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Emotional distress in delirium was recently characterized as anxiety, depression, acute and posttraumatic stress (Rose et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2021). Understanding patients and family members’ experiences of delirium would help to clarify it nature and inform the development of targeted nonpharmacologic interventions (Williams et al., 2020).

Hence, this study aimed to examine and synthesize qualitative data on patient and family member delirium experiences and relieving factors to facilitate conceptual clarity for the nature and mediators of delirium and its related distress in the ICU.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis (PROSPERO CRD42020156705) and here report our findings according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009) and the Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement (Tong et al., 2012). We chose this research approach because qualitative meta-synthesis is conducive to developing theoretical and conceptual understanding and informing clinical interventions and research programs (Tong et al., 2012).

2.2. Search Strategy

Pre-planned search terms were devised by the study team, which included a university research librarian, and formulated according to setting (ICU), condition (delirium), perspectives (patient and family member) and study type (qualitative). The search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane and Clinicaltrials.gov in November 2019 and February 2021 using Boolean logic, adapted to syntax and subject headings of each database. Filters included English language and publication since 1980 (first entry for delirium in the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). The full database search strategy is in Supplementary File. We performed a lateral search of citations of included articles and relevant systematic reviews (Bélanger and Ducharme, 2011, Finucane et al., 2017, O’Malley et al., 2008) and clinical practice guidelines (Barr et al., 2013, Devlin et al., 2018).

We included qualitative studies containing adult patient or family member quotes relevant to delirium in the ICU published in a peer-reviewed journal. Qualitative studies were defined as those using methodologies such as phenomenology, ethnography, grounded theory, hermeneutics, narrative or thematic analysis, and/or primarily analysing textual rather than numerical data. Included articles reported participant quotes about delirium in qualitative studies of overall experience of the ICU, and mixed-methods and qualitative sub-studies of observational or interventional studies, if all other inclusion criteria were met. Articles reporting only clinicians’ perspectives and experiences of delirium in the ICU were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Search results were imported into Endnote X8 then exported to Covidence after removal of duplicates (Department of Health, 2008). Five reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and performed full-text reviews to identify eligible articles in duplicate (i.e., two reviewers per article). Eligible data was extracted data into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet which included: i) general study and sample characteristics; ii) methods; iii) participants’ quotes; and iv) themes and conclusions. Themes and conclusions were extracted into a separate spreadsheet so that coders were blinded to author themes and interpretations. Throughout, disagreements were resolved by discussion and evaluation by a third reviewer, where required. Cohen’s kappa ranged κ=0.02–0.44 for title/abstract screening and κ=0.10–0.79 for full text screening. Full details of inter-relater reliability are in Supplementary File.

2.4. Appraisal of Methodological Quality

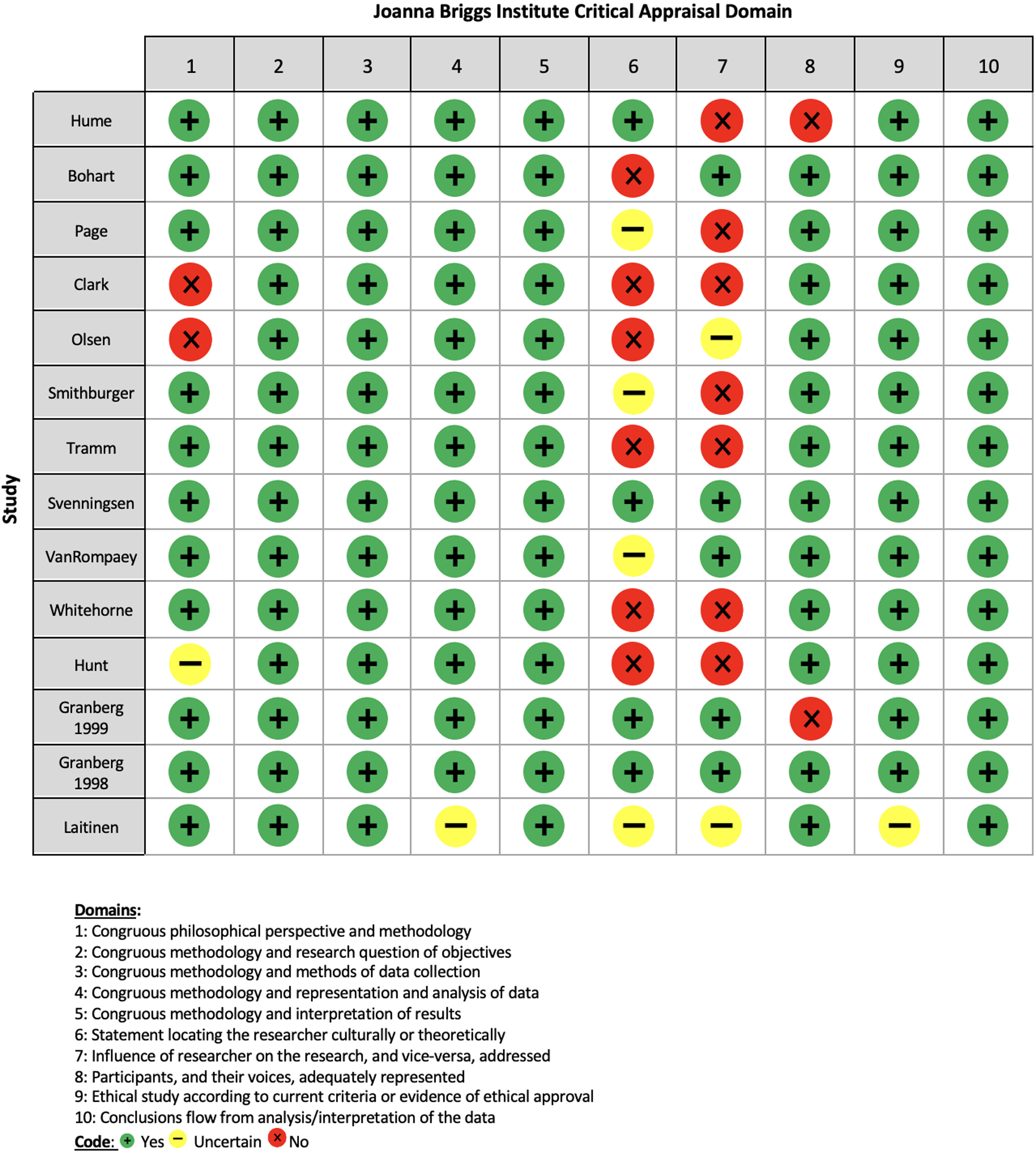

The 10-item Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research guided evaluation of the quality of included articles (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). Two researchers independently evaluated each article. Disagreements were also resolved by discussion and additional evaluation. A predetermined minimum of ‘yes’ for six domains was required for inclusion.

2.5. Data Synthesis

We used Thomas and Hardens’ three stage thematic synthesis approach: i) line-by-line coding of relevant texts; ii) organisation of codes into descriptive themes; and iii) development of analytical themes (Thomas and Harden, 2008). Initial deductive coding of quotes relevant to patients’ delirium experience were framed against the five core domains articulated by Maldonado (2018) (i.e., cognitive, psychomotor, emotional, circadian rhythm, and consciousness/attentional disturbances). Quotes not fitting into Maldonado’s domains were then inductively coded (i.e., informed by raw data, not an a priori theory or framework). Coding for mediators during delirium was inductive, as was development of descriptive and analytical themes. Microsoft Excel was used to organise data during analysis.

2.6. Rigor, trustworthiness, and reflexivity

Our study prioritized patient and family member perspectives and experiences by only analyzing participants’ quotes, not authors’ themes or interpretations. Patient and family member quotes were separately analyzed to elucidate distinct themes for each group. The international and multidisciplinary team included academic nurses, research assistants, a physician (role: concept/aim development, interpretation, and dissemination), and a university librarian (role: key words and search), who collectively have expertise in research, critical care, palliative care, and delirium. The nursing and assistant researchers were all trained in qualitative methods and conducted study selection (AH, LMB, ACJ), extraction (ACJ, CFG), appraisal (LMB, AAS, CV, AH), and synthesis (patient quotes: AAS, CV, AH; family quotes: LMB, ACJ, CFG). After study selection, team members communicated regularly via email and Zoom meetings to perform the meta-synthesis and interpret the findings. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and evaluation by a third reviewer, where required. We presented our preliminary analytical themes to five people (two patients and three family members) who experienced delirium during critical illness and incorporated their suggestions in the final analytical themes.

3. RESULTS

Our systematic search of the published qualitative literature yielded 3238 identified articles, of which 14 articles reporting 13 studies were included (Figure 1; Table 1). The studies (1996–2020) were conducted in Europe (n=8, 57%) (Bohart et al., 2019; Granberg et al., 1999,;Granberg et al., 1998; Laitinen, 1996; Olsen et al., 2017; Page et al., 2019; Svenningsen et al., 2016; Van Rompaey et al., 2016), North America (n=3, 22%) (Clark et al., 2017; Smithburger et al., 2017; Whitehorne et al., 2015), Australia (n=2, 14%) (Hunt, 1999; Tramm et al., 2017), and South Africa (n=1, 7%) (Hume, 2020). Various qualitative methodologies were used, most commonly hermeneutics and/or phenomenology (n=7, 54%). Quality assessment revealed that most studies met most Joanna Briggs Institute criteria, except that reporting of the position of the researchers and reflexivity was rarely present (Figure 2; Supplementary File). Three studies were situated within larger observational or interventional studies (Smithburger et al., 2017; Svenningsen et al., 2016; Tramm et al., 2017). No study used a theoretical or conceptual framework. Twelve articles (86%) reported interview methods, ranging from no pre-established questions to being highly structured; only three reported questions about what helped participants during delirium (Bohart et al., 2019), confusion (Smithburger et al., 2017), or admission to an ICU (Tramm et al., 2017) (Supplementary File). Half of authorship teams were nurses only (n=7, 50%); the remainder were multidisciplinary or single author.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow chart of initial searches and inclusion (1980 - Feb 2021)

Table 1:

Summary of included studies

| Author (first), year, author disciplines | Country | Aim | Setting | Participants | Methods | Findings (Themes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hume, 2020 Master of Music and Health Communication student |

South Africa | To understand the experience of ICU delirium perspectives of patients, healthcare professionals, and families; explore relationships between delirium and working cultures/environment of the ICU; and assess potential for music composition to contribute to understanding of delirium | Private teaching hospital, ICU, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: Patients who experienced delirium in the ICU, without dementia or other pre-existing neurocognitive disorders, three or more months after the delirious episode; their family members; and health care professionals Participated: N=11 (3 patients, 2 family members, 10 health care professionals), 27% male Delirium status not reported |

Phenomenological and narrative approach to semi-structured interviews, unstructured observation and focus groups; qualitative content analysis; and musical composition of findings |

|

|

Bohart, 2019 [29] Nurse (1), Medical Doctor (1), Health Scientist (1) |

Denmark | To explore relatives’ experiences of ICU delirium in critically ill patients | Level II ICU medical/surgical 11-bed ICU; 24-hour open visiting policy, single patient rooms |

Eligible: Caregivers aged ≥18 of patients with ≥48hour ICU stay and delirium Participated: n=11, 27% male, mean age 64 |

10 question semi-structured interview; phenomenological approach followed by Malterud’s four-step systematic text condensation. |

|

|

Page, 2019 [34] Nurse (3) |

United Kingdom | To understand and form a substantive theory about the critical illness trajectory from patient and relative perspectives. | 14-bed critical care unit in 800 bed district hospital, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: survivors of critical illness and their family members Participated: 16 survivors, mean age 61, 63% male 4–40 days in unit and 15 family members, 20% male Delirium ascertainment process/status not reported |

In-depth interviews 4–11 months post discharge. Constructivist grounded theory coding using constant comparative method. |

|

|

Clark, 2017 [35] Medical Doctor (5), Nurse (1), Social Work (1), Research (1) |

United States | To understand experiences of ICU survivors with alcohol misuse during transition from hospital to home | Two 44-bed medical ICUs and a mixed medical/surgical ICU across three hospitals, visitation policies not reported |

Eligible: ICU survivors with an alcohol use score of ≥ 5 (women) or ≥ 8 (men), ≥18 and their family/friends Participated: 50 survivors mean age 50, 80% male and 22 family/friends, mean age 50, 38% male |

Semi-structured interviews 3-months post discharge; collected baseline demographic and clinical information. Team-based general inductive approach to analysis. |

|

|

Olsen, 2017 [31] Nurse (3) |

Norway | To investigate how adult patients experienced the ICU stay and their recovery period. Usefulness of an information pamphlet about what to expect and how to survive after an ICU stay | 14-bed ICU, visiting hours 11.00–19.00, ICU nurses offer visit exceptions on individual basis |

Eligible: ICU patients aged ≥18, mechanically ventilated for ≥48hrs, Norwegian speaking and home dwelling with no prior nursing services or cognitive impairment Participated: n=30; 67% male, aged 20–80 Delirium ascertainment process/status not reported |

Two semi-structured interviews. First interview on ward after ICU discharge and second interview by telephone three months after hospital discharge. Qualitative content analysis. |

|

|

Smithburger, 2017 [36] Pharmacist (3), Nurse (1) |

United States | To gain insight into patients’ families’ opinions on active participation in delirium-prevention activities | 24-bed medical ICU at an academic medical center, open visitation |

Eligible: ICU patients’ family members who previously participated in a delirium survey Participated: n=10, median age 55, 20% male, 40% spouse, 40% child, 20% sibling or parent Patient characteristics not reported |

In-depth semi-structured interviews until thematic saturation using grounded theory. |

|

|

Tramm, 2017 [26] Medical Doctor (1), Nurse (2), Health Scientist (3) |

Australia | To explore experiences of family members of patients treated with ECMO | ICU, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: Family caregivers of ICU patients treated with ECMO who had participated in a larger cohort study, English speaking and without a cognitive, neurological or terminal condition Participated: n=10, 40% male, aged 31–65, 80% spouse, 20% mother, 80% working, 10% retired, 10% household duties, 100% lived with patient Patient characteristics: mean age 38, 70% male, ventilated median 11 days; 5 had delirium during median 21 days in ICU Delirium status not reported |

Qualitative descriptive methodology guided by naturalist enquiry. Open-ended semi-structured interviews 12–15 months after ECMO treatment. Six-step thematic analysis process incorporating deduction and induction. |

|

|

Svenningsen, 2016 [28] Nursing (3) |

Denmark | To describe former ICU patients’ memories of delusions | Three medical-surgical ICUs, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: Patients admitted >48hrs to ICU who were sedated and had delirium Participated: n=114, mean age 61, 57% male, 59% surgical, 56% delirious at least once in the ICU |

Qualitative explorative, phenomenological hermeneutics approach to text analysis inspired by Ricoeur’s interpretation theory. Interviews at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 6 months after ICU discharge. Naïve reading and structural analysis on three levels: quotes, meaning, and theme identification. |

|

|

van Rompaey, 2016 [27] Nursing (5) |

Belgium | To describe ICU patients’ perception of delirium | Public hospital surgical ICU and medical ICU, each with 12 beds, visitation policies not reported |

Eligible: Adult patients who experienced delirium in the ICU, English or Dutch speaking, glasgow coma scale ≥13 time of interview, ICU stay ≥24hrs Participated: n=30, 57% male, mean age 65, delirium duration mean 73 hours (n=25), delirium onset mean 7 days (n = 27) |

Two independent researchers analyzed data using hermeneutic spiral based on text, followed by interpretation of researchers, association with patient’s world, and reflection and revision of text. |

|

|

Whitehorne, 2015 [37] Nursing (4) |

Canada | To understand the experience patients in the ICU who experienced delirium | ICUs of two acute care hospitals, visitation policies not reported |

Eligible: delirious adult ICU patients without dementia and able to read and speak English Participated: n=10, 70% male, aged 46–70 |

Qualitative Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology. Semi-structured interview after patient was no longer delirious and willing to participate. Four existentials (space, body, time, human relations) guided analysis. Themes identified by researchers focusing on whole experience, identifying meaningful phrases, and engaging in interpretation. |

|

|

Hunt, 1999 [25] Nurse (1) |

Australia | To understand the experience of nursing care in the ICU from patients’ points of view and determine what nursing care behaviors are important to them and why | ICU, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: Adult ICU patients, English speaking, legally competent and admitted for elective cardiac bypass Participated: n=12, demographic characteristics not reported Delirium status not reported |

2 semi-structured interviews. Interview 1: participants described their preconceptions, assumptions, beliefs, and knowledge of nursing care; Interview 2: described their experiences of nursing care in the ICU. First and second interview data separately analyzed using thematic extraction. |

|

|

Granberg, 1999 [32] Nurse (2) Medical Doctor (1) |

Sweden | To describe and illuminate patients’ experiences of acute confusion, disorientation, dreams and nightmares, or so-called ‘unreal’ experiences during and after their ICU stay | 10-bed medical/surgical ICU, visitation policy not reported, but previously reported in Granberg 1998 (below) |

Eligible: Patients who had been ventilated and in ICU ≥36hrs, without addiction to alcohol and/or narcotics, severe psychiatric conditions, cardiopulmonary resuscitation that was not wholly successful, or primary unconsciousness Participated: n= 19 mean age 50, 68% male Delirium status not reported |

Semi-structured interview 6–10 days after ICU discharge, second interview 4–8 weeks later, using a hermeneutic approach to collection, analysis and interpretation. |

|

|

Granberg, 1998 [33] Nurse (2) Medical Doctor (1) |

Sweden | To describe and analyze patients’ experiences in order to gain knowledge and understanding about ICU syndrome | 10-bed medical/surgical ICU, visitation policy: close relatives allowed to visit patients, encouraged to carry out basic care | As per Granberg 1999 above | As per Granberg 1999 above |

|

|

Laitinen, 1996 [30] Nurse (1) |

Finland | To describe and reflect upon the confusion experienced by patients in the ICU after a cardiac bypass | ICU, visitation policy not reported |

Eligible: Patients ≥ 2 days in the ICU post cardiac bypass Participated: n=10, demographic characteristics not reported Delirium status not reported |

Phenomenological hermeneutic approach to free discussion between researcher and participant 4–8 days following cardiac bypass. Thematic and pattern analysis. |

|

Abbreviations:ECMO=Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU=Intensive Care Unit

Feelings reported in this study were: fear, anger, frustration, guilt, shame, incomprehension, loneliness, restlessness, tired, joy (after delirium). Bolded = no exemplar quotes provided

Figure 2:

Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal of Included Studies

There were 364 participants (294 patients, 70 family members). When reported, most patients were male (59%), and most family members were female (71%). The average age of patient and family members was 58 and 55 years, respectively.

The nine studies that explicitly focused on participants’ experiences of delirium (Bohart et al., 2019; Hume, 2020; Smithburger et al., 2017; Van Rompaey et al., 2016; Whitehorne et al., 2015), delusions (Svenningsen et al., 2016), confusion (Laitinen, 1996), “acute confusion, disorientation, dreams and nightmares” (Granberg et al., 1999), and “ICU syndrome” (Granberg et al., 1998) provided 237 of the overall 255 quotes included in the meta-synthesis (93%). Of note, only five articles confirmed patient participants’ delirium via structured assessment, using either the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (Ely, 2016) or the Neelon and Champagne Confusion Assessment Scale (Neelon et al., 1996).

3.1. Qualitative meta-synthesis

Data extraction yielded 164 quotes by patients and 91 quotes by family members for qualitative meta-synthesis (n=255). Initial categorisation of data relevant to patients’ experience of delirium found almost all aligned with Maldonado’s conceptual model of the core domains of delirium, except for feelings of impending death, recovery, and one recount of a flashback. Review of preliminary analytical themes by the additional patients and family members we consulted with elucidated the need for distinction between patient experience during delirium versus after delirium. Meta-synthesis ultimately resulted in four major themes. Themes with key exemplary quotations are presented below and in Table 2.

Table 2:

Key supporting quotes per theme

| Themes | Supporting quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| The nature of the ICU delirium experience | ||

| 1. Patients’ ICU delirium-related distress was experienced by the whole person | a. Patients with ICU delirium felt frightened, angry, misunderstood, empty, frustrated and overwhelmed, and afterwards ashamed, embarrassed and guilty |

|

| b. In addition to emotional distress, patients experienced cognitive, physical, relational, and spiritual suffering during ICU delirium |

|

|

| 2. Family members felt compassion, uncertainty, and anxiety during ICU delirium, as well as apprehension about the future |

|

|

| Mediators of ICU delirium-related distress | ||

| 3. During ICU delirium, patients valued nurses’ presence, kindness, and explanations; and thoughts of family and home |

|

|

| 4. During ICU delirium, family members valued communication with the ICU team, being involved in the patient’s care, and signs of their recovery |

|

|

3.1.1. The nature of the acute ICU delirium experience (179/255 quotes, 70%)

3.1.1a. Theme 1: ICU patient’s delirium-related distress was experienced by the whole person (149/255 quotes, 58%)

Patients experienced distress during and after delirium in all aspects of their being, encompassing emotional, cognitive, physical, relational, and spiritual suffering. Theme 1 therefore explicitly acknowledges the ‘whole person’ experience of delirium (Maldonado, 2018; Rose et al., 2017). During delirium, patients felt frightened, angry, misunderstood, empty, frustrated, and overwhelmed. The predominantly reported emotion was fear (14/35 40% patient quotes), as exemplified by this patient describing being “scared, really scared” during delirium. Fear was often coupled with delusions and incomprehension:

“I climbed around in the mountains and had to kill a lot of people to return. It felt so real and frightening. I couldn’t get away and I couldn’t find the solution.”

Patients also described being misunderstood, “angry”, “upset”, “frustrated”, “emptied of feelings”, and that “the delirium was so overwhelming.” In contrast, after ICU delirium patients felt ashamed, embarrassed, and guilty about succumbing to it and their “bad” behavior, along with the need to apologize:

“…I hit one of the nurses right on the chest, like this. I remembered that when she came into the room … and I asked her if she was the one I’d hit. She said ‘Yes’, and I apologized. I felt horrible about it … When I think about it I feel awful [starts to cry]. I’ve thought about this a few times, how I could possibly do such a thing [pauses]. But it’s over and forgotten, I hope.”

In addition to emotional distress, patients experienced cognitive, physical, relational, and spiritual suffering during delirium. Perceptual distortions, disorientation, and impaired comprehension caused patients to misunderstand their sensations and the environment, describing it as “very disorienting. I didn’t know if it was night or day. I had all these scenarios going on in my mind…” Patients described being physically “tied down” and “put in straps”, suggesting distressing experiences of being physically restrained. They felt frightened and overwhelmed by other interventions describing “…lay[ing] there completely still. I did not dare to move.” Patients also misunderstood the actions and intentions of ICU staff:

“I was restrained and forced to be treated. A mask with too much air was forced on me - like holding the head out the car door - panic! The nurse got suspicious because I wasn’t supposed to touch my throat.”

Patients found it hard to connect and communicate with others, such as this patient’s description of attempts to communicate, “I could and wanted to ask something to the nurse … but I had no idea how to start a conversation.” The nearness of death was described by some: “I thought I was going to die” and “I couldn’t breathe”. Others believed that staff were trying to “abduct” or “kill” them. Patients also remembered dreams of crossing borders and being in other worlds:

“I was dreaming I passed the border; it was the end, and everything turned dark.”

3.1.1b. Theme 2: During delirium, family members felt compassion, uncertainty, and anxiety, as well as apprehension about the future (30/255 quotes, 12%)

Family members were acutely aware of the patient’s fear and agitation:

“He was so agitated that he just kept screaming my name.”

Many described patients’ disorientation and perceptual distortions:

“He has been confused about where he was and what had happened…”

(Ex sister-in-law)

“Because he accused one of the boys of putting bananas down his tube and trying to kill him, and this particular lad was special, he was lovely, he did an awful lot for you, and, yeah, ‘He’s trying to kill me! He’s trying to kill me’.”

(Spouse)

Despite compassionate recognition of what the patient was experiencing, they were uncertain and puzzled by it:

“I thought she was very restless, and I thought it was strange that she pulled the lines. I thought, why is she doing that? And I said, ‘You must not pull all the lines’.”

(Daughter)

Anxiety made it difficult to take in information:

“…but you can’t retain everything because you’re so—how do I want to say? Nervous, anxious, scared yourself for your loved one.”

Family members were also apprehensive about the future, wondering if the patient would fully recover from the delirium and the critical illness:

“Things are difficult, but … but I wonder a lot about how it’s going to be at the end.”

(Spouse)

3.1.2. Mediators of delirium-related distress (76/255 quotes, 30%)

3.1.2a. Theme 3: During ICU delirium, patients valued nurses’ presence, kindness, and explanations; and thoughts of family and home (15/255 quotes, 6%)

The relatively few patient quotes about what helped them during delirium indicated nurses’ presence, words, and actions that conveyed kindness and safety were appreciated:

“Uneasiness, coldness -- that was what I felt. Not all the time … it always stopped when the nurse came near me…The presence of this nurse was quite … quite important.”

One patient described eye contact with the nurse as “the one most important thing”. Patients also felt relieved when nurses’ conveyed understanding, forgiveness, and provided explanations:

“I cursed, but they understood. They are used to it. Some of the nurses even forgave me.”

“When something crossed my mind, I called for the nurse and asked for an explanation.”

Thoughts of home bolstered patience and hope, as one patient described, “The feeling of being at home for a while gave me more patience; now I knew that I would return home.” Importantly, patients spoke about the comfort, protection and guidance provided by family members, including those who were not physically present, or even alive:

“There were two paths to follow: One was a tunnel, and the light at the end of the tunnel was shiny and bright; it almost whispered to me: ‘stop breathing and you will get there’. But fortunately, my daughter was at the end of the other path. She was pregnant and I had to survive to see my grandchild. Perhaps this is why I was still breathing after so many weeks. In a strange way my kids and grandkids were always with me, and there were even some of my deceased relatives hanging from the ceiling. It wasn’t even scary; they didn’t do any harm. I don’t think they wanted to bother me, and somehow it was even comforting.”

3.1.2b. Theme 4: During ICU delirium, family members valued communication with the team, being involved in the patient’s care, and signs of their recovery (61/255 quotes, 24%)

Communication with the team about delirium helped family members to make sense of the situation. When staff explained delirium, this helped to allay families’ fears and doubts. As one spouse described, “I was relieved when I heard about delirium because it explained what I have been seeing.” However, some family members recounted vague descriptions of delirium by clinicians. When describing interactions with the nurse about delirium, a patient’s spouse recalled being told, “‘he is a bit sad today’, ‘he is a little confused today’, ‘he is very tired today’.” Families want to be better informed about delirium, preferring“…to get information, and as much information as I could from the health care provider, and to know the status.” Many wanted to be informed and prepared for delirium early in the ICU admission:

“[Y]ou had this fine, perfectly healthy parent and all of a sudden you’re in the ICU. So, I think as soon as you get there, or close, somebody just might want to pull you aside and say, ‘Hey, here are some helpful hints while you’re in here. You might want to review this, just because we’ve talked to people, we see this all the time, and this could help’.”

Family involvement in care benefitted both the family and the patient. Family members described engaging with and comforting the delirious patient using phrases like “You just go to sleep. I’ll be here; I’ll keep you safe.” recalling that “it seemed to help a little bit.” Being with the patient was perceived as beneficial for them because family members could engage the patient in ways that were more familiar and meaningful. For example, family members brought items that were part of the patient’s usual life.

“I mean, she’s like a real news person, and so even though the TV was on the whole time, I brought the newspaper in and I read the headlines and stuff that she’d be interested in hearing about.”

“I would just say have them bring books, or cards, or something and like in a normal routine. You know what I mean? Well, like if it’s an older person and like they enjoy doing puzzles, or puzzle books and stuff like that. Bring the puzzles, or the cards, or whatever they’re used to doing.”

Families valued being engaged and included in efforts to orient the patient. When the clinical team included the family in basic care, it gave them a sense of purpose and usefulness to both the patient and staff.

“We tried getting our own whiteboard and putting a calendar on it so that she knew what day of the week it was. Because, you know, the whiteboards don’t always get updated by the nurses.”

“And, like a list as a reminder, things that I can do, to help the patient or—and even help the nurse … I know they’re strapped on their time.”

Furthermore, families felt relieved when delirious patients showed signs of recovery:

“Now he’s much more clear about his thinking. I mean we can see it. He is different from then to now.”

4. DISCUSSION

This study systematically identified, reviewed, and synthesized 14 qualitative articles to explore the delirium experience and mediators of delirium for patients and their families in the ICU. Key patient and family-centric insights regarding ICU delirium-related distress include: articulation of the distinct emotions experienced during and directly after delirium (e.g., fear, anger, shame, uncertainty); its ‘whole person’ nature (e.g., emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual); and the value that patients and family members placed on clinician compassion, communication, and connectedness. Our findings highlight the need for humane environments, practices, and interactions as the primary means to address ICU delirium-related distress for both patients and their families. We propose an approach to critical care that values and addresses more than just patients’ urgent physiological needs. Future research testing interventions for ICU delirium-related distress would be enhanced by a consensus definition of delirium-related distress and the use of specific measures of predominant emotions.

Our findings of the emotional aspects of delirium align with those from studies in other settings, where patients who experienced delirium similarly reported fear, anger, confusion, disconnection and humiliation, and family members experienced concern and uncertainty in the face of inadequate information - both preparatory and explanatory - from clinicians (Bélanger and Ducharme, 2011; Finucane et al., 2017; O’Malley et al., 2008). Current findings build upon a recent narrative review of distress in delirium which, while it flagged that patients experience longer-term psychological distress, did not distinguish between emotions experienced in the acute episode from those felt in its immediate aftermath (Williams et al., 2020). This meta-synthesis identified that directly after delirium (as distinct from during or longer-term), the nature of patient’s emotional distress shifts from being predominantly fear, to feelings of shame, embarrassment, and guilt. This nuance is important, because it refines understanding of the trajectory of delirium-related distress and illuminates specific targets and time points for its assessment and intervention, both in clinical practice and future studies. Relevant measures of specific emotions in future delirium studies include the short forms for anxiety, anger, and emotional and behavioral dyscontrol, within the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) (HealthMeasures, 2020).

However, patients described not just emotional distress, but also that which was cognitive, physical, relational, and spiritual in nature. It was also situational, as distress during delirium was intensified by the ICU environment (e.g., noise leading to lack of sleep), interventions (e.g., intubation, oxygen mask, restraints), and the proximity of death. This finding aligns with previous studies where patients recalled distress in delirium to be interrelated with many factors; namely, longer duration and greater severity of delirium (overall, and of its cognitive/behavioral symptoms), poorer functional status, and the circumstances of the underlying illness and treatment (Williams et al., 2020). The latter hints at the proposed role of repeated or prolonged exposure to stress in the pathophysiology of delirium, underscoring why humane ICU environments and interventions are essential (Maldonado, 2018; Wilson et al., 2019).

The findings of this qualitative meta-synthesis indicate that patients and family members value simple, compassionate interpersonal communication and actions by clinicians before, during, and after delirium as a means for relieving distress. While this finding was based on relatively fewer quotes, it again speaks to the necessity for humane intensive care (Hume, 2020). We therefore propose that person-centered, multicomponent approaches are required to relieve delirium-related distress for patients and their families. An envisaged patient intervention would incorporate timely identification and treatment of the causes of the delirium to reduce its duration, early mobility to optimize function, and modifying the ICU environment (e.g., reducing noise at night, promoting natural light) (Ely, 2017). Additional measures to reduce distress are to address physical comfort (e.g., management of pain/dyspnea), minimize (or cease) restraint use, and reassure the patient of their safety (Davidson et al., 2017). Immediately after delirium resolves, interventions could shift to compassionate inquiry of the patient about their experience, followed by explanation and education to help allay feelings of shame, humiliation, and guilt associated with actions during a delirium episode.

Findings regarding the whole person nature of delirium-related distress from both this meta-synthesis and other literature could inform development of a consensus definition of the construct (Williams et al., 2020). A consensus definition of delirium-related distress would be pivotal, as greater conceptual clarity would lead to standardized measures and targeted interventions. An exemplar is the National Comprehensive Cancer Network definition for cancer-related distress, which delineates its multifactorial and holistic nature that extends along a continuum from common (i.e., ‘normal’) and mildly unpleasant feelings to crisis (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020). Based on this definition, the developed clinician and patient guidance in early recognition of (e.g., screening using the Distress Thermometer and intervention for cancer-related distress) (Partridge et al., 2019; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020). Developing a similar consensus definition for delirium-related distress and subsequent initiatives would ideally be a shared enterprise by the international delirium societies.

4.1. Implications for Nursing Practice

Nurses are well placed and suited to communicating human kindness and empathy towards patients who are frightened and ashamed from delirium in the ICU. Furthermore, our study highlights the importance and potential benefits of nurses involving family members in patient care, especially considering their knowledge of the patient as a person (e.g., likes, dislikes, stressors) is key information for the critical care team (Wilson et al., 2019). Nurses can also encourage family members to provide physical touch (e.g., holding hands), personal hygiene (e.g., oral care, hair brushing), and communication (e.g., news, family updates) to the patient (Wilson et al., 2019). Engaging family in clinical decision-making and involving them in interdisciplinary rounds is similarly vital to providing patient- and family-centered care (Burns et al., 2018; Davidson et al., 2017). In these ways, nurses can enlist family members in personalized critical care that better meets individual patients’ fundamental human needs.

4.2. Limitations

Strengths of this study include the systematic approach to study retrieval and data synthesis; international representation of included studies; and prioritization of patient and family voices, including our incorporation of additional feedback from persons with experience of delirium in the ICU. Limitations include that we only accessed, included, and analyzed published quotes and not the full range obtained in the original studies; inclusion of only English language studies; included studies being predominantly conducted in Western countries; and only five studies reporting confirmed delirium as an inclusion criterion. Lastly, the Cohen’s kappa for our title/abstract and full text screening was very low across reviewers; despite this, consensus was agreed for all included studies. These limitations may have contributed to selection, measurement, and cultural biases; however, these biases were moderated by the research team’s cultural and discipline diversity and expertise in delirium.

5. CONCLUSION

This study found ample qualitative data indicating that the delirium experience has emotional, cognitive, physical, relational, spiritual, and situational dimensions for patients and family members. In contrast, there has been less attention to what patients and their families perceive as beneficial in relieving this distress, which should be the focus of future exploratory studies. Qualitative studies in this field should address researcher bias by improved reporting of reflexivity, along with interdisciplinary study teams that include persons with experience of delirium. Development of a consensus definition for delirium-related distress would provide a standardized description of its nature and dimensions, in turn informing subjective and consistent outcome measures in future delirium intervention studies in critical care, and other settings.

Supplementary Material

CONTRIBUTION OF THE PAPER.

What is already known about the topic?

Delirium is common, debilitating and distressing for patients with critical illness.

A 2020 narrative review characterized delirium-related distress as a primarily emotional experience and concluded that improved understanding of the psychological experience of delirium would enable supportive interventions for patients and their families to be developed.

A 2021 core outcome set for research evaluating interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium in critically ill adults included emotional distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, acute and posttraumatic stress) as a core outcome in delirium research.

What this paper adds?

Patients with delirium in the Intensive Care Unit experienced distress with their whole person, not just emotionally.

The numerous qualitative studies of patients’ and family members’ perspectives and experiences of delirium in the Intensive Care Unit have largely neglected to investigate patient-reported mediators of delirium.

Mediators of delirium-related distress that were reported included humane interpersonal approaches to care (patients); and communication, and information from clinicians and involvement in the patient’s care (family members).

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the patient and family caregivers who reviewed the preliminary themes and provided valuable feedback.

Funding Sources:

LMB is currently receiving grant funding from NHLBI (#K12HL137943-01). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health or Vanderbilt University.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association, 1980. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publisher, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Geélinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM, Coursin DB, Herr DL, Tung A, Robinson BRH, Fontaine DK, Ramsay MA, Riker RR, Sessler CN, Pun B, Skrobik Y, Jaeschke R, 2013. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine 41 (1), 263–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger L, Ducharme F, 2011. Patients’ and nurses’ experiences of delirium: a review of qualitative studies. Nursing in Critical Care 16 (6), 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohart S, Merete Møller A, Forsyth Herling S, 2019. Do health care professionals worry about delirium? Relatives’ experience of delirium in the intensive care unit: A qualitative interview study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, Dittus RS, Gill TM, Bernard GR, Ely EW, Girard TD, 2014. Delirium in the ICU and subsequent long-term disability among survivors of mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Medicine 42 (2), 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KEA, Misak C, Herridge M, Meade MO, Oczkowski S, 2018. Patient and Family Engagement in the ICU. Untapped Opportunities and Underrecognized Challenges. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 198 (3), 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BJ, Jones J, Reed KD, Hodapp R, Douglas IS, Van Pelt D, Burnham EL, Moss M, 2017. The Experience of Patients with Alcohol Misuse after Surviving a Critical Illness. A Qualitative Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 14 (7), 1154–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino A, Covanti S, Rossi Monti M, Starcevic V, 2016. Emotion dysregulation: A review of the concept and implications for clinical practice. European Psychiatry 33, S528–S529. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung CL, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon AA, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy MM, Azoulay E, Curtis JR, 2017. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med 45 (1), 103–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, 2008. End of Life Care Strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, Watson PL, Weinhouse GL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, Balas MC, van den Boogaard M, Bosma KJ, Brummel NE, Chanques G, Denehy L, Drouot X, Fraser GL, Harris JE, Joffe AM, Kho ME, Kress JP, Lanphere JA, McKinley S, Neufeld KJ, Pisani MA, Payen J-F, Pun BT, Puntillo KA, Riker RR, Robinson BRH, Shehabi Y, Szumita PM, Winkelman C, Centofanti JE, Price C, Nikayin S, Misak CJ, Flood PD, Kiedrowski K, Alhazzani W, 2018. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 46 (9), e825–e873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, 2016. Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU), The Complete Training Manual. Vanderbilt University, Nashville, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, 2017. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Critical Care Medicine 45 (2), 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane AM, Lugton J, Kennedy C, Spiller JA, 2017. The experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium, and their role in its management in palliative care settings: an integrative literature review. Psycho-Oncology 26 (3), 291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg A, B. EI, Lundberg D, 1999. Acute confusion and unreal experiences in intensive care patients in relation to the ICU syndrome. Part II. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 15 (1), 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granberg A, Bergbom Engberg I Fau - Lundberg D, Lundberg D, 1998. Patients’ experience of being critically ill or severely injured and cared for in an intensive care unit in relation to the ICU syndrome. Part I. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 14 (6), 294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthMeasures, 2020. Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Hume VJ, 2020. Delirium in intensive care: violence, loss and humanity. Medical Humanities, medhum-2020–011908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JM, 1999. The cardiac surgical patient’s expectations and experiences of nursing care in the intensive care unit. Australian Critical Care 12 (2), 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak KD, Stelfox HT, Leigh JP, Ely EW, Fiest KM, 2018. Incidence and Prevalence of Delirium Subtypes in an Adult ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis*. Critical Care Medicine 46 (12), 2029–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen H, 1996. Patients’ experience of confusion in the intensive care unit following cardiac surgery. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 12 (2), 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Sweeney R, Barber V, Page V, Ely EW, Perkins GD, Young JD, McAuley DF, on behalf of the Intensive Care, F., 2010. A national survey of the management of delirium in UK intensive care units. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 103 (4), 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado JR, 2018. Delirium pathophysiology: An updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 33 (11), 1428–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG, 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6 (7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, Myatra SN, Salluh JIF, Amare D, Azoulay E, Bellelli G, Csomos A, Fan E, Fagoni N, Girard TD, Heras La Calle G, Inoue S, Lim CM, Kaps R, Kotfis K, Koh Y, Misango D, Pandharipande PP, Permpikul C, Cheng Tan C, Wang DX, Sharshar T, Shehabi Y, Skrobik Y, Singh JM, Slooter A, Smith M, Tsuruta R, Latronico N, 2017. Worldwide Survey of the “Assessing Pain, Both Spontaneous Awakening and Breathing Trials, Choice of Drugs, Delirium Monitoring/Management, Early Exercise/Mobility, and Family Empowerment” (ABCDEF) Bundle. Critical Care Medicine 45 (11), e1111–e1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Distress Management.

- Neelon VJ, Champagne MT, Carlson JR, Funk SG, 1996. The NEECHAM Confusion Scale: construction, validation, and clinical testing. Nursing Research 45 (6), 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley G, Leonard M, Meagher D, O’Keeffe ST, 2008. The delirium experience: a review. Journal of Psychsomatic Research 65 (3), 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen KD, Nester M, Hansen BS, 2017. Evaluating the past to improve the future - A qualitative study of ICU patients’ experiences. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 43, 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page P, Simpson A, Reynolds L, 2019. Constructing a grounded theory of critical illness survivorship: The dualistic worlds of survivors and family members. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28 (3–4), 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge JSL, Crichton S, Biswell E, Harari D, Martin FC, Dhesi JK, 2019. Measuring the distress related to delirium in older surgical patients and their relatives. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 34 (7), 1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, Scott TA, Pun BT, Okahashi J, Strength C, Pandharipande P, Girard TD, Burgess H, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW, 2009. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Critical Care Medicine 37 (3), 825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose L, Agar M, Burry LD, Campbell N, Clarke M, Lee J, Siddiqi N, Page VJ, 2017. Development of core outcome sets for effectiveness trials of interventions to prevent and/or treat delirium (Del-COrS): study protocol. BMJ Open 7 (9), e016371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose L, Burry L, Agar M, Campbell NL, Clarke M, Lee J, … & Page V (2021). A Core Outcome Set for Research Evaluating Interventions to Prevent and/or Treat Delirium in Critically Ill Adults: An International Consensus Study (Del-COrS). Critical Care Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim AA, Ely EW, 2017. Delirium the under-recognised syndrome: survey of healthcare professionals’ awareness and practice in the intensive care units. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26 (5–6), 813–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithburger PL, Korenoski AS, Alexander SA, Kane-Gill SL, 2017. Perceptions of Families of Intensive Care Unit Patients Regarding Involvement in Delirium-Prevention Activities: A Qualitative Study. Critical Care Nurse 37 (6), e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsen H, Egerod I, Dreyer P, 2016. Strange and scary memories of the intensive care unit: a qualitative, longitudinal study inspired by Ricoeur’s interpretation theory. Journal of Clinical Nursing 25 (19–20), 2807–2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Qualitative Research.

- Thomas J, Harden A, 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research 8 (45). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J, 2012. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12 (1), 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramm R, Ilic D, Murphy K, Sheldrake J, Pellegrino V, Hodgson C, 2017. Experience and needs of family members of patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26 (11–12), 1657–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rompaey B, Van Hoof A, van Bogaert P, Timmermans O, Dilles T, 2016. The patient’s perception of a delirium: A qualitative research in a Belgian intensive care unit. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 32, 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehorne K, Gaudine A, Meadus R, Solberg S, 2015. Lived experience of the intensive care unit for patients who experienced delirium. American Journal of Critical Care 24 (6), 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ST, Dhesi JK, Partridge JSL, 2020. Distress in delirium: causes, assessment and management. European Geriatric Medicine 11 (1), 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ME, Beesley S, Grow A, Rubin E, Hopkins RO, Hajizadeh N, Brown SM, 2019. Humanizing the intensive care unit. Critical Care 23 (1), 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.