Abstract

Lyme disease is a tick-borne infectious disease caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex. However, the distribution of Borrelia genospecies and the tissue detection rate of Borrelia in wild rodents have rarely been investigated. Here, we studied 27 wild rodents (Apodemus agrarius) captured in October and November 2016 in Gwangju, South Korea, and performed nested polymerase chain reaction targeting pyrG and ospA to confirm Borrelia infection. Eight rodents (29.6%) tested positive for Borrelia infection. The heart showed the highest infection rate (7/27; 25.9%), followed by the spleen (4/27; 14.8%), kidney (2/27; 7.4%), and lungs (1/27; 3.7%). The B. afzelii infection rate was 25.9%, with the highest rate observed in the heart (7/27; 25.9%), followed by that in the kidney and spleen (both 2/27; 7.4%). B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto were detected only in the spleen (1/27; 3.7%). This is the first report of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto infection in wild rodents in South Korea. The rodent hearts showed a high B. afzelii infection rate, whereas the rodent spleens showed high B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto infection rates. Besides B. garinii and B. afzelii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto may cause Lyme disease in South Korea.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Diseases, Molecular medicine

Introduction

Lyme borreliosis is a vector-borne disease characterized by polymorphic clinical manifestations (cutaneous, rheumatological, and neurological) that is mostly reported in North America, Europe, and Asia. The spirochetes that cause Lyme borreliosis can spread to other tissues and organs and cause serious multisystem infection involving the skin, nervous system, joints, or heart1–4. In the United States, changes in land use practices and a marked increase in the deer population have increased the risk of exposure to ticks infected with Lyme disease-causing spirochetes5. James et al. reported the need for environmental studies on tick abundance and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection in ticks for reducing exposure risk and predicting future trends in pathogen prevalence and distribution patterns in response to environmental changes6.

The Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex (comprising Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii, among others) causes Lyme disease. The genospecies of this complex are transmitted by different species of ticks (e.g., Ixodes scapularis and I. persulcatus) and are responsible for causing Lyme borreliosis in humans in different geographical regions4,7,8. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is known to cause Lyme disease in North America, and, less extensively, in Europe. At least five Borrelia species (B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. spielmanii, and B. bavariensis) have been identified that cause Lyme disease in Europe. B. afzelii and B. garinii are the predominant species in Europe, whereas B. garinii is predominant in Asia. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only species known to cause Lyme borreliosis in northern America, but has rarely been detected in Asia3,4. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was isolated for the first time from a human skin biopsy sample in Taiwan9. However, to our knowledge, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto has not been isolated in Japan or South Korea to date10.

In South Korea, B. burgdorferi sensu lato was first isolated from Ixodes ticks and the rodent species Apodemus agrarius in 199211. In 2002, nine B. afzelii strains were isolated from Ixodes nipponensis and A. agrarius in Chungju, South Korea, and their heterogeneous characteristics, which were different from those of previously reported B. afzelii strains, were identified using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) of the ospC gene and rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic space12. Moreover, in 2020, the prevalence and distribution of five B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies (B. afzelii, B. valaisiana, B. yangtzensis, B. garinii, and B. tanukii) were reported based on the results of nested PCR targeting partial flagellin B gene sequences and sequencing in ticks isolated from wild rodents in South Korea13.

Lyme disease is a Group 3 infectious disease in South Korea, and the number of cases reported to the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency has gradually increased from 2011 to 2020, with an average of 15.4 cases reported per year, and 31, 23, 23, and 12 cases reported each year from 2017 to 2020, respectively14.

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is confirmed based on positive results in an indirect immunofluorescence assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay via western blot analysis or by isolating and identifying the pathogen from clinical specimens from patients, including blood samples. In addition, the molecular techniques used for classifying and identifying Borrelia spp. and B. burgdorferi include PCR targeting rRNA genes, flaB, recA, p66, and the plasmid-encoded gene ospA; DNA-DNA homology analysis, ribotyping, PCR-RFLP analysis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting, multilocus sequence typing/multilocus sequence analysis, and whole genome sequencing2,15–21. The process of culturing clinical specimens to detect B. burgdorferi is labor-intensive, expensive, and applicable only to untreated patients, and therefore, is not used in clinical practice. However, microorganisms can be directly detected in clinical specimens using PCR, and their genotype can be confirmed through sequencing without isolating the pathogens17. Nested PCR is known to exhibit a sensitivity 100 times greater than that of conventional PCR; hence, nested PCR can be used to increase the diagnostic sensitivity for Lyme disease17,22. Nested PCR targeting the rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer and ospA (encoding the outer surface protein A) gene or the 16S rRNA and pyrG (encoding CTP synthase) genes was performed, along with sequence analysis, to detect Borrelia DNA in clinical samples17,20.

In this study, we investigated the infection rate in 27 wild rodents (A. agrarius) captured in October and November 2016 using nested PCR targeting the Borrelia-specific genes pyrG and ospA and direct DNA sequencing with rodent tissue samples. The distribution and infection rate of Borrelia genospecies in wild rodents, which serve as reservoirs for the pathogens of tick-borne infectious disease, have rarely been investigated. In addition, we reported the rates of Borrelia infection in the different organs of the wild rodents and investigated the differences in the organ-specific detection rate of each Borrelia species.

Results

PCR and tissue detection rates of Borrelia species in captured wild rodents

Twenty-seven wild rodents were captured using Sherman live traps during October and November 2016 in two regions of Gwangju City in South Korea. All captured rodents were identified as A. agrarius. Borrelia-specific pyrG and ospA nested PCR revealed that 8 of the 27 rodents were infected with the pathogens in the spleen, kidney, lungs, and heart (Table 1).

Table 1.

PCR detection of Borrelia species in the organs of wild mice†.

| No. of captured mice | Lung | Spleen | Heart | Kidney | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

pyrG N-PCR |

ospA N-PCR |

pyrG N-PCR |

ospA N-PCR |

pyrG N-PCR |

ospA N-PCR |

pyrG N-PCR |

ospA N-PCR |

|

| 10-1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-3 | − | − | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | − | − |

| 10-4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-5 | − | − | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | − | |

| 10-6 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-8 | − | − | + (B. burgdorferi) | + (B. burgdorferi) | − | − | − | − |

| 10-10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-11 | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. garinii) | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | − |

| 10-12 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10-13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-1 | − | − | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) |

| 11-2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 11-5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-6 | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | − | |

| 11-7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-8 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 11-9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-11 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-12 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-13 | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | − | + (B. afzelii) | − | − | − |

| 11-14 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11-15 | − | − | − | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | + (B. afzelii) | − | − |

†pyrG, CTP synthase gene; ospA, outer surface protein A gene; N-PCR, nested PCR; −, negative; +, positive.

In pyrG nested PCR, the overall rate of positive response to Borrelia species was 29.6% (8/27). Among the studied organs, the detection rate was the highest in the heart (25.9%, 7/27). The kidney and spleen showed positive detection rates of 7.4% (2/27) and 14.8% (4/27), respectively. The B. afzelii infection rate was 25.9% (7/27) in the wild rodents. The heart showed the highest positive detection rate (25.9%, 7/27), and the kidney and spleen had a positive detection rate of 7.4% (2/27), respectively. The infection rate for both B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was 3.7% (1/27), and both bacteria were detected only in the spleens.

In ospA nested PCR, the heart tissues from 6 of 27 wild rodents exhibited a positive response to B. afzelii, with an infection rate of 22.2%. The infection rate was 3.7% (1/27) in the spleen, kidney, and lung tissues. In a wild rodent that showed a Borrelia-positive result in pyrG nested PCR (Chosun M10-8 Sp, which indicates the spleen of wild rodent no. 8 captured in October 2016), B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was also detected by ospA nested PCR in the spleen.

Using pyrG nested PCR, the B. afzelii infection rate was found to be 25% (3/12) in October and 26.7% (4/15) in November, and the hearts of the animals showed the highest infection rate in both months. With respect to B. garinii, a positive response was detected in the spleen of only one animal captured in October (Chosun M10-11 Sp). This animal exhibited co-infection with B. garinii (detected in the spleen) and B. afzelii (detected in the heart, kidney, and lungs). Additionally, infection by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the spleen was confirmed in only one wild rodent captured in October (Chosun M10-8 Sp).

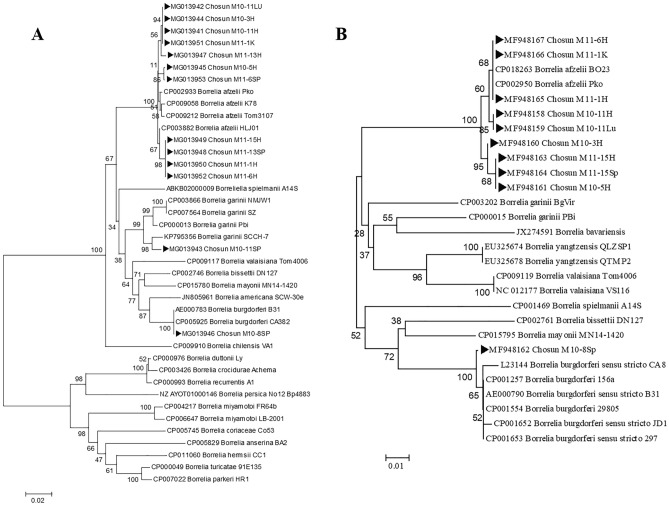

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the partial nucleotide sequences of pyrG (675 bp) and ospA (285 bp) segments obtained from Borrelia-positive tissue specimens and various Borrelia strains, such as B. afzelii HLJ01, B. garinii SCCH-7, and B. burgdorferi B31, among others, from GenBank. The phylogenetic trees generated using the pyrG and ospA gene sequences exhibited similar topologies. All pyrG sequences obtained from the heart, kidneys, spleen, and lungs of the wild rodents (M10-3, M10-5, M10-11, M11-1, M11-6, M11-13, and M11-15) clustered with B. afzelii. Additionally, the pyrG sequences from the spleen of M10-11 (Chosun M10-11Sp) formed a cluster with B. garinii, whereas the pyrG sequences from the spleen of another wild rodent (Chosun M10-8 Sp) formed a cluster with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A phylogenetic tree constructed using the pyrG (A, 675 bp) and ospA (B, 285 bp) sequences retrieved from GenBank and obtained from the tissue DNA of the wild rodents captured (▶). The scale bars indicate 0.02 (A) or 0.01 (B) base substitutions per site. The GenBank accession numbers are shown in the tree.

We evaluated the similarities between Borrelia pyrG (675 bp) and ospA (285 bp) nucleotide sequences obtained from GenBank and Borrelia-positive tissue specimens using LaserGene v6 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Sequence similarity comparison showed that the pyrG sequences obtained from the organs of wild rodents (Chosun M10-3H, M10-5H, M10-11H and 10-11Lu, M11-1H and 11-1K, M11-6H and 11-6Sp, M11-13H and 11-13Sp, and M11-15H) exhibited more than 99% similarity with the pyrG sequences from B. afzelii HLJ01 strains isolated from Chinese patients (GenBank accession number CP003882). Moreover, B. garinii DNA isolated from the spleen of M10-11 (Chosun M10-11 Sp) exhibited more than 98.4% homology with the pyrG gene sequence of B. garinii strain SCCH-7 isolated from rodents in the USA (GenBank accession number KP795356). Lastly, the pyrG DNA of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolated from the spleen of M10-8 (Chosun M10-8 Sp) showed 100% and 99.4% similarity to that of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31_NRZ strain isolated from I. scapularis (GenBank accession number AE000783) and of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 strain isolated from human cerebrospinal fluid in the USA (GenBank accession number KF170281), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Similarity between Borrelia pyrG gene sequences from GenBank and the wild rodents captured in this study†.

| Genospecies of Borrelia | Strains | Origin of Borrelia strain | pyrG accession number | M10-3H | M10-5H | M10-8Sp | M10-11H | M10-11Lu | M10-11Sp | M11-1H | M11-1K | M11-6H | M11-6Sp | M11-13H | M11-13Sp | M11-15H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Geographic | ||||||||||||||||

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | B31 | Ixodes scapularis | USA | AE000783 | 91.9 | 91.9 | 100 | 91.9 | 91.9 | 92.4 | 92 | 91.9 | 92 | 92.1 | 91.7 | 92 | 92 |

| 297 | Human cerebrospinal fluid | USA | KF170281 | 91.4 | 91.6 | 99.4 | 91.4 | 91.4 | 91.8 | 91.6 | 91.4 | 91.6 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 91.6 | 91.6 | |

| B. garinii | 20047 | I. ricinus | France | CP028861 | 92.9 | 92.6 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 98.4 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.7 | 92.6 | 92.9 | 92.9 |

| NP81 | I. persulcatus | Japan | AB555842 | 83 | 83.9 | 83.3 | 83 | 83 | 88.4 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 82.8 | 82.7 | 83 | 83 | |

| SCCH-7 | Peromyscus gossypinus (cotton mouse) | USA | KP795356 | 92.9 | 92.6 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 98.4 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.7 | 92.6 | 92.9 | 92.9 | |

| B. afzelii | BO23 | Human skin | Sweden | CP018262 | 99.1 | 98.9 | 92.1 | 99.1 | 99.1 | 93.3 | 99 | 99.1 | 99 | 98.8 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| HLJ01 | Human | China | CP003882 | 99.4 | 99.2 | 92.1 | 99.4 | 99.4 | 93.2 | 99.6 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.4 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | |

| B. bissettii | DN127 | I. pacificus | USA | CP002746 | 92.6 | 92 | 94.4 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 93.5 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.1 | 92.9 | 92.6 | 92.6 |

| B. spielmanii | A14S | Human skin | Netherlands | ABKB02000009 | 92.9 | 92.6 | 93.3 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 92.1 | 92.6 | 92.9 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 92.6 |

| B. valaisiana | VS116 | I. ricinus | Switzerland | ABCY02000001 | 91.3 | 91.3 | 93.5 | 91.3 | 91.3 | 92.9 | 91.1 | 91.3 | 91.1 | 91.3 | 90.8 | 91.1 | 91.1 |

| B. sinica | CMN3 | Niviventer sp. | China | AB526135 | 82.5 | 83.5 | 81.8 | 82.5 | 82.5 | 82.6 | 82.4 | 82.5 | 82.4 | 82.2 | 82.1 | 82.4 | 82.4 |

†pyrG, CTP synthase gene.

The nucleotide sequence comparison of ospA from Chosun M10-8 Sp infected with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains revealed a high variability in the degree of sequence similarity, ranging from 73.7 to 99.6%. The ospA sequences of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolated from Chosun M10-8 Sp exhibited 99.6% similarity with those of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 strain (GenBank accession number AE000790) and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 strain isolated in the USA (GenBank accession number CP001653) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Similarity between Borrelia ospA gene sequences from GenBank and wild rodents captured in this study†.

| Genospecies of Borrelia | Strains | Origin of Borrelia strain | ospA accession number | M10-3H | M10-5H | M10-8Sp | M10-11H | M10-11Lu | M11-1H | M11-1 K | M11-6H | M11-15H | M11-15Sp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Geographic | |||||||||||||

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | B31 | Ixodes scapularis | USA | AE000790 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 99.6 | 88.8 | 88.8 | 88.4 | 88.4 | 88.4 | 88.8 | 88.8 |

| TWKM5 | Rattus norvegicus | Taiwan | AF369941 | 64.6 | 64.2 | 73.7 | 64.6 | 64.6 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 64.2 | |

| IP1 | Human cerebrospinal fluid | France | DQ111052 | 74.4 | 74 | 83.2 | 74 | 74 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 74 | 74 | |

| Sh-2-82 | I. dammini | USA | DQ393311 | 74.4 | 74 | 83.2 | 74 | 74 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 74 | 74 | |

| 297 | Human CSF | USA | CP001653 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 99.6 | 88.8 | 88.8 | 88.4 | 88.4 | 88.4 | 88.8 | 88.8 | |

| B. garinii | 20047 | I. ricinus | France | CP028862 | 90.9 | 90.5 | 89.1 | 91.9 | 91.9 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 90.5 | 90.5 |

| B. afzelii | VS461 | I. ricinus | Switzerland | Z29087 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 89.1 | 99.3 | 99.3 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.3 | 99.3 |

| BO23 | Human skin | Sweden | CP018263 | 99.3 | 98.9 | 88.8 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.9 | 98.9 | |

| J1 | I. persulcatus | Japan | KM069290 | 84.9 | 84.6 | 75.4 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.9 | 84.9 | 84.9 | 84.6 | 84.6 | |

| B. bissettii | DN127 | I. pacificus | USA | CP002761 | 87.4 | 87 | 90.9 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87 | 87 |

| B. spielmanii | A14S | Human skin | Netherlands | CP001469 | 87.7 | 87.4 | 88.1 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.4 |

| B. valaisiana | VS116 | I. ricinus | Switzerland | NC_012177 | 88.1 | 87.7 | 88.8 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.4 | 87.7 | 87.7 |

†ospA, outer surface protein A.

Discussion

Lyme disease is a zoonotic disease transmitted by ticks and caused by the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex, a group comprising approximately 20 species. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. valaisiana, and B. lusitaniae have been reported to cause the disease23.

In this study, we performed nested PCR targeting the pyrG and ospA genes of Borrelia species and detected infection by Borrelia genospecies, including B. afzelii, B. garinii, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, in A. agrarius, with a 29.6% (8/27) positive detection rate for Borrelia species.

In a study conducted in 2008, conventional PCR targeting ospC, a gene specific to Borrelia, was performed using genomic DNA extracted from 1618 ticks (420 pools) and 369 rodents (A. agrarius) captured close to the demilitarized zone of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Contrary to our results, the positive rate for B. burgdorferi sensu lato infection was found to be 1% (16/420) in ticks; however, the Borrelia infection rate in rodents was not reported24. We attempted to retrieve additional published reports on the detection rate of Borrelia genospecies in wild rodents, including A. agrarius, in South Korea; however, we did not find such reports. Recently, the B. afzelii detection rate was reported in ticks parasitizing domestic and wild animals in South Korea, including ticks from mammals (1.8%), horses (1.4%), wild boar (5.3%), native Korean goats (5.9%), and Korean water deer (0.8%), based on a nested PCR experiment targeting the 5S–23S rRNA of Borrelia25.

Borrelia species are transmitted primarily by Ixodes species, including I. ricinus and I. persulcatus in Europe, I. scapularis in North America, I. nipponensis in Japan, and I. persulcatus in China. Furthermore, in South Korea, I. persulcatus, I. nipponensis, I. granulatus, and I. ovatus have been reported as competent vectors of Borrelia23,26. In South Korea, B. burgdorferi sensu lato was isolated from Ixodes ticks and A. agrarius in 1993, and B. afzelii was isolated from I. nipponensis and A. agrarius in 200211,12. Recently, B. garinii strain 935T was isolated from I. persulcatus ticks in South Korea. However, besides a single report on whole-genome sequencing, no other study has reported the detection of this organism in wild rodents or ticks23.

In the present study, a high positive detection rate for B. afzelii (25.9%) was found in specimens obtained from captured wild rodents, and the highest rate was observed in the heart tissues. While B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto infection was also detected (3.7%), these bacteria only infected the spleen. In 2020, Cadavid et al. reported that when immunosuppressed adult Macaca mulatta were inoculated with B. burgdorferi, B. burgdorferi exhibited tropism for the meninges in the central nervous system and for connective tissues. Additionally, significant inflammation was noted only in the heart, and immunosuppressed animals inoculated with B. burgdorferi exhibited cardiac fiber degeneration and necrosis27. In 2017, Grillon et al., reported that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. afzelii target the skin of mice regardless of the route of inoculation and cause persistent skin infection28. These results differ from ours, probably because we detected Borrelia spirochetes from each organ of the captured wild rodents, whereas Grillon et al. detected Borrelia from each organ after inoculating a susceptible animal.

Lyme disease spirochetes exhibit strain- and species-specific differences in tissue tropism. For example, infection by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii, the three major spirochetes causing Lyme disease, is characterized by distinct but overlapping clinical signs. Infection by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the most common causative agent of Lyme disease in the USA, is closely associated with arthritis, whereas that by B. garinii is related to neuroborreliosis, and that by B. afzelii is related to acrodermatitis (a type of chronic skin lesion). B. burgdorferi and B. garinii isolates were shown to cause severe arthritis in immunocompromised mice in animal studies29,30. The correlation between pancarditis and the marked tropism of B. burgdorferi in cardiac tissues was also reported in studies involving the autopsy of patients with sudden cardiac deaths associated with Lyme carditis31.

Lyme borreliosis spirochetes exhibit a high detection rate in a specific organ depending on the species, which could suggest a certain preference for the organ. These findings suggest that Lyme borreliosis spirochetes infecting rodents can be detected in the heart and spleen tissues, as B. afzelii exhibit a high detection rate in rodent hearts, whereas B. garinii and B. burgdorferi exhibit high detection rates in rodent spleens. According to Matuschka et al., infected Norway rats that served as reservoirs for Lyme disease spirochetes increased the infection risk for visitors to a city park in central Europe32. Based on the relatively high rate of Borrelia infection (29.6%) in the captured rodents in this study, the risk of Lyme disease in the Gwangju city, South Korea is predicted to be high. Therefore, additional research should be conducted to study the causative agents of Lyme disease in South Korea and further elucidate their prevalence and tissue tropism.

In conclusion, this is the first study to show the presence of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in rodents captured in South Korea. B. afzelii, one of the causative agents of Lyme disease, exhibited a high positive detection rate (25.9%) in wild rodents, specifically in the heart tissues, captured in the areas around a metropolitan city in the southwestern region of South Korea, whereas B. garinii and B. burgdorferi exhibited high detection rates in the spleen.

Our findings suggest that along with B. garinii and B. afzelii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto may also act as a causative agent of Lyme disease in South Korea, and different Borrelia species exhibit different tissue detection rates.

Methods

Study site and rodent capture

Wild rodents were captured using Sherman live traps (3″ × 3.5″ × 9″, USA) in two regions of Gwangsan-gu (35°09′19.2″ N, 126°45′05.4″ E) and Buk-gu (35°13′51.7″ N, 126°54′23.8″ E) in Gwangju Metropolitan City, South Korea, in October and November 201633. The two regions in which the mouse traps were placed are located on a boundary that divides the urban and rural areas, and there were five types of locations (fallow ground, a ridge between rice fields, a boundary between a forest and field, area surrounding tombs, and area surrounding water) selected in both regions. For capturing wild rodents, 10 Sherman live traps were placed on a deserted area at each location once a month in October and November. Peanut butter-coated biscuits were used as the bait for the wild rodents, and the traps were set at approximately 10 a.m. and removed at approximately 8 p.m. Twenty-seven rodents were captured (twelve in October and fifteen in November). After capture, the animals were euthanized via inhalation of 5% isoflurane in accordance with an approved animal use protocol, and the spleen, kidneys, lungs, and heart were harvested and stored at − 20 °C33.

DNA isolation

Approximately 25 mg of tissue specimens collected from the wild rodents were ground using a cell strainer (70 μm; Falcon, Corning, NY, USA) and 180 μL of ATL buffer from the QIAamp DNA Blood and Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The tissue suspension was treated with 20 µL of proteinase K and incubated overnight at 56 °C for complete tissue lysis. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood and Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR amplification

To detect Borrelia DNA, nested PCR targeting the pyrG and ospA genes of Borrelia species was performed using genomic DNA extracted from the tissue specimens. For pyrG nested PCR, pyrG-1F/pyrG-1R primers (for the initial PCR step) and pyrG-2F/pyrG-2R primers (for nested PCR) were used20. For ospA nested PCR, Borrel-ospAF1/Borrel-ospAR1 primers (for the initial PCR step) and Borrel-ospAF2/Borrel-ospAR2 primers (for nested PCR) were used17. The primer sequences are listed in Table 4. PCR was performed using the AmpliTaq Gold 360 Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an Applied Biosystems Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler. An enzyme reaction solution of 20 µL was used in the primary PCR; this solution was composed of 1 μL each of the forward and reverse primers (5 μM), 10 μL of Master Mix, 2 μL of a GC enhancer, and 4 μL of distilled water. Nested PCR was performed with the same reaction solution used in the initial PCR step, using the initial PCR product as the template. PCR was performed using gene-specific PCR primers at specific annealing temperatures under the following cycling conditions: 10 min at 94 °C for the pre-denaturation step, 30 cycles of 20 s at 94 °C, 30 s at the different annealing temperatures, 30 s–1 min at 72 °C, and a final extension step of 7 min at 72 °C. In each PCR run, a negative control (reaction mixture without the template DNA) was included. The genomic DNA of B. burgdorferi B31 Clone 5A1 was used as the positive control. The annealing temperatures are listed in Table 4. Upon the completion of PCR, the products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

Table 4.

Oligonucleotide primers and PCR conditions used in this study†.

| PCR | Primer name (sequence) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTP synthase gene (pyrG) (external primer) | pyrG-1F (5′-ATTGCAAGTTCTGAGAATA-3′) | 45 | 801 | 20 |

| pyrG -1R (5′-CAAACATTACGAGCAAATTC-3′) | ||||

| CTP synthase gene (pyrG) (internal primer) | pyrG-2F (5-′GATATGGAAAATATTTTATTTATTG-3′) | 49 | 707 | 20 |

| pyrG-2R (5′-AAACCAAGACAAATTCCAAG-3′) | ||||

| Borrel-ospAF1 (5′-GGGAATAGGTCTAATATTAGC-3′) | 52 | 427 | 17 | |

| Outer surface protein A (ospA) (external primer) | Borrel-ospAR1 (5′-CTGTGTATTCAAGTCTGGTTCC-3′) | |||

| Outer surface protein A (ospA) (internal primer) | Borrel-ospAF2 (5′-CAAAATGTTAGTAGCCTTGAT-3′) | 52 | 314 | 17 |

| Borrel-ospAR2 (5′-TCTGTTGATGACTTGTCTTT-3′) |

†bp, base pair; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Nucleotide sequencing

A QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) was used to purify the PCR products, which were directly sequenced using the PCR primers and an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 3730XL DNA analyzer; Applied Biosystems) at Solgent (Deajeon, South Korea). To identify the bacteria, the sequences were analyzed using the BLAST network service (Ver 2.33; http://www.technelysium.com.au/chromas.html) available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD, USA).

Sequence similarity and phylogenetic analyses

The DNA sequence identity, contig generation, and homology comparison were confirmed using Lasergene v6 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA) and the NCBI BlastN network service. After the sequences were concatenated, LaserGene v6 (DNASTAR) was used for sequence alignment and homology comparison.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the partial sequences of pyrG (675 bp) and ospA (285 bp) obtained from the organ tissues of the wild rodents and from various Borrelia strains (listed in GenBank) using the neighbor joining method. ClustalX (version 2.0; http://www.clustal.org/) and Tree Explorer (DNASTAR) were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. To increase the reliability of the tree, bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates. The sequence data generated in this study were submitted to NCBI GenBank (accession numbers MG013941 to MG013953 and MF948158 to MF948167), and the reference sequences were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chosun University. All rodents were euthanized in accordance with an animal use protocol approved by the Chosun University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CIACUC) under the approval number CIACUC2016-A0003. The study was conducted in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of animal studies.

Author contributions

C.M.K. designed the study, participated in data collection and laboratory analysis (such as molecular analysis), wrote the original manuscript, and revised the draft during the course of submission. D.-M.K. designed and coordinated the study and contributed to the drafting and reviewing of the manuscript during the course of submission. S.Y.P. was responsible for performing the experiments and collecting the data. J.W.P. and J.G.C. captured the wild rodents and helped draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data and materials are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr Updates on Borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public health. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Diagnosis of lyme borreliosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:484–509. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.484-509.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steere AC. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:115–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2012;379:461–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piesman J, Gern L. Lyme borreliosis in Europe and North America. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl):S191–S220. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003004694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James MC, et al. Environmental determinants of Ixodes ricinus ticks and the incidence of Borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme borreliosis, Scotland. Parasitology. 2013;140:237–246. doi: 10.1017/S003118201200145X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picken RN, et al. Identification of three species of Borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii) among isolates from acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans lesions. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998;110:211–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steere AC, et al. Lyme borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16090–214. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao LL, Chen YJ, Shih CM. First isolation and molecular identification of Borreliaburgdorferi sensu stricto and Borreliaafzelii from skin biopsies of patients in Taiwan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;15:E182–E187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyamoto, K., Masuzawa, T. J. L. b. b., epidemiology & control. Ecology of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Japan and East Asia. 201–222 (2002).

- 11.Park KH, Chang WH, Schwan TG. Identification and characterization of Lyme disease spirochetes, Borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato, isolated in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31:1831–1837. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1831-1837.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, et al. Characterization of Borreliaafzelii isolated from Ixodesnipponensis and Apodemusagrarius in Chungju, Korea, by PCR-rFLP analyses of ospC gene and rrf (5S)-rrl (23S) intergenic spacer. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;46:677–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Kim TK, Kim TY, Lee HI. Geographical Distribution of Borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato in ticks collected from wild rodents in the Republic of Korea. Pathogens. 2020 doi: 10.3390/pathogens9110866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Infectious Disease Portal. http://www.kdca.go.kr/npt/biz/npp/ist/bass/bassDissStatsMain.do (accessed on 03 May 2021).

- 15.Asbrink E, Hovmark A, Hederstedt B. Serologic studies of erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans with indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1985;65:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbour AG. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YJ, et al. First molecular detection of Borreliaafzelii in clinical samples in Korea. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;51:1201–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb04015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson BJ, et al. Serodiagnosis of Lyme disease: Accuracy of a two-step approach using a flagella-based ELISA and immunoblotting. J. Infect. Dis. 1996;174:346–353. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma B, Christen B, Leung D, Vigo-Pelfrey C. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by western immunoblot: Reactivity of various significant antibodies against Borreliaburgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:370–376. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.370-376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sapi E, et al. Improved culture conditions for the growth and detection of Borrelia from human serum. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013;10:362–376. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, G. et al. Molecular typing of Borreliaburgdorferi. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol.34, 12C.15.11–12C.15.31 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kim DM, et al. Usefulness of nested PCR for the diagnosis of scrub typhus in clinical practice: A prospective study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;75:542–545. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noh Y, et al. Whole-genome sequence of borrelia garinii strain 935T isolated from Ixodespersulcatus in South Korea. Genome Announc. 2014 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01298-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chae JS, et al. Microbial pathogens in ticks, rodents and a shrew in northern Gyeonggi-do near the DMZ, Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2008;9:285–293. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo MG, Kwon OD, Kwak D. Molecular identification of Borreliaafzelii from ticks parasitizing domestic and wild animals in South Korea. Microorganisms. 2020 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanek G, Reiter M. The expanding Lyme Borrelia complex—Clinical significance of genomic species? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:487–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadavid D, O'Neill T, Schaefer H, Pachner AR. Localization of Borreliaburgdorferi in the nervous system and other organs in a nonhuman primate model of Lyme disease. Lab. Investig. 2000;80:1043–1054. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grillon A, et al. Identification of Borrelia protein candidates in mouse skin for potential diagnosis of disseminated Lyme borreliosis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16719. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16749-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig-Mylius KA, Lee M, Jones KL, Glickstein LJ. Arthritogenicity of Borreliaburgdorferi and Borreliagarinii: Comparison of infection in mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;80:252–258. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin YP, et al. Strain-specific variation of the decorin-binding adhesin DbpA influences the tissue tropism of the Lyme disease spirochete. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004238. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muehlenbachs A, et al. Cardiac tropism of Borreliaburgdorferi: An autopsy study of sudden cardiac death associated with Lyme carditis. Am. J. Pathol. 2016;186:1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matuschka FR, et al. Risk of urban Lyme disease enhanced by the presence of rats. J. Infect. Dis. 1996;174:1108–1111. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park JW, et al. Seroepidemiological survey of zoonotic diseases in small mammals with PCR detection of Orientiatsutsugamushi in chiggers, Gwangju, Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2016;54:307–313. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available upon request to the corresponding author.