Abstract

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is associated with germline deleterious variants in CDH1 and CTNNA1. The majority of HDGC-suspected patients are still genetically unresolved, raising the need for identification of novel HDGC predisposing genes. Under the collaborative environment of the SOLVE-RD consortium, re-analysis of whole-exome sequencing data from unresolved gastric cancer cases (n = 83) identified a mosaic missense variant in PIK3CA in a 25-year-old female with diffuse gastric cancer (DGC) without familial history for cancer. The variant, c.3140A>G p.(His1047Arg), a known cancer-related somatic hotspot, was present at a low variant allele frequency (18%) in leukocyte-derived DNA. Somatic variants in PIK3CA are usually associated with overgrowth, a phenotype that was not observed in this patient. This report highlights mosaicism as a potential, and understudied, mechanism in the etiology of DGC.

Subject terms: Cancer genomics, Gastric cancer

Introduction

In ~10% of the gastric cancer (GC) cases familial aggregation is observed [1]. Two monogenic GC-associated syndromes have been described so far: (i) Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer syndrome (HDGC; MIM 137215) [2], and (ii) Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach syndrome (GAPPS) [3].

HDGC is associated with germline deleterious variants in CDH1 and CTNNA1. However, deleterious variants in CDH1 or CTNNA1 are identified in only 10-40% of families fulfilling HDGC clinical criteria [2, 4, 5]. PALB2 and MYD88 are considered candidate genes for HDGC that need further confirmation [6, 7].

Currently, a large proportion of clinically and pathologically confirmed HDGC families and individuals developing diffuse gastric cancer (DGC) at very young age remain genetically unresolved, raising the need for research on novel inherited predisposing factors. Here, we report the case of a 25-year-old female with DGC, in whom a mosaic PIK3CA variant was identified in leukocyte-derived DNA by re-analysis of whole-exome sequencing (WES) data by the SOLVE-RD consortium.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

Between January 2019 and September 2019 members of the European Reference Network on genetic tumor risk syndromes (ERN-GENTURIS) submitted 294 unresolved germline WES and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) datasets from genetic tumor risk syndrome suspected individuals for re-analysis to SOLVE-RD. From this initial 294 unresolved cases, 83 had a phenotype of non-GAPPS gastric cancer that were reanalyzed in the present study. This study was approved by local ethics committees (local study identification numbers: Ipatimup: 152/18; University of Cambridge: 97/5/032; Radboudumc: 2018-4985, 2018-4986).

Re-analysis of WES data

For each case, sequencing reads were processed using the RD-Connect Genome-Phenome Analysis Platform standardized analysis pipeline based upon GATK3.6 best practices (further information: http://solve-rd.eu/ and http://rd-connect.eu/). Subsequently, all variants with a read-depth ≥8-fold and a genotype quality of ≥20 were selected for downstream processing and interpretation. Each variant was annotated using VEP from Ensembl as described by Matalonga et al. [8]. For re-analysis of WES data submitted by ERN-GENTURIS, variants present in a gene list composed of 229 genes associated with genetic tumor risk syndromes (Supplementary Table 1) were assessed for their pathogenicity as annotated by ClinVar. Variants predicted to be pathogenic or likely pathogenic were followed up for interpretation and validation.

Raw whole-exome data of this patient is available via the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA; accession number EGAZ00001545545). The variant described in this manuscript is submitted to the Leiden Open Variant Database (LOVD; https://databases.lovd.nl/shared, Individual ID number 00327392).

Validation by smMIP sequencing

Genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood was screened in triplicate for hotspot regions (codons 345, 420, 539-554, 1043-1050) of PIK3CA (NM_006218.4) using small molecule molecular inversion probes (smMIP) sequencing as described by Steeghs et al. [9].

Results

Clinical phenotype

A 25-year-old female presented with abdominal discomfort for two months when endoscopic investigation of the stomach revealed a gastric mass. After total gastrectomy a diffuse type gastric adenocarcinoma (T2N1M0) was identified in the antrum of the stomach. The patient tested negative for H. pylori infection and no other coexisting disorders or congenital abnormalities were reported. Immunohistochemical P53 expression in the tumor showed a wild-type pattern. The patient was treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil, etoposide and cisplatin, but she deceased 12 months after diagnosis due to peritoneal metastasis, ileus of the small bowel, ascites and cachexia.

Germline analysis

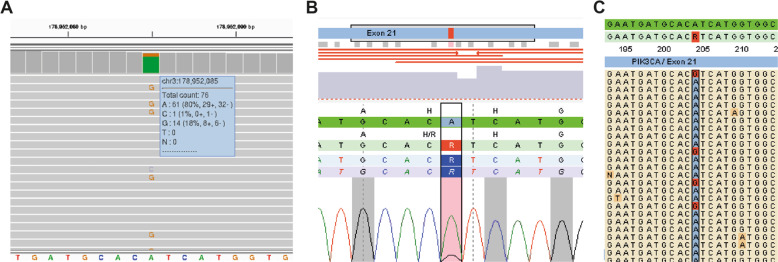

The patient did not have a family history of gastric cancer, but due to her very early-onset of DGC she met the clinical criteria for testing for HDGC [10]. In absence of a germline CDH1 variant that is predicted to impair protein function, the patient was selected for WES analysis, but putative disruptive variants in cancer predisposition genes were not identified [11]. Re-analysis of the generated WES data within the SOLVE-RD consortium revealed one ClinVar-reported missense variant in PIK3CA (NM_006218.4; c.3140A>G; p.(His1047Arg)), a gene associated with somatic overgrowth syndromes, but not previously associated with gastric cancer [12, 13]. This variant was present in blood leukocytes at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 18% (14/76 sequencing reads), suggesting presence in mosaic state (Fig. 1A). Triplicate smMIP sequencing confirmed mosaicism of PIK3CA c.3140A>G, with a VAF ranging from 13% to 16% (Fig. 1B,C). Germline genetic testing was performed on genomic DNA extracted from leukocytes that were taken from the patient prior to chemotherapy. No tumor tissue was available for further histopathological assessment or somatic sequencing.

Fig. 1. Mosaic PIK3CA c.3140A>G variant found in leukocyte DNA of the proband.

A Screenshot of the Integrative Genomics Viewer. Alternative alleles at PIK3CA c.3140 position are marked. Variant details are shown in the panel on the right. B Screenshot of one outcome of the in triplicate smMIP screened leukocyte-derived DNA from the proband. The PIK3CA (c.3140A>G; p.(His1047Arg)) variant is marked in red. C Screenshot of individual reads in smMIP analysis. Alternative alleles at PIK3CA c.3140 position are marked in red.

Variant characteristics

PIK3CA c.3140 is a known somatic hotspot location in many cancer types, including gastric tumors [14]. Variants in PIK3CA are found in 15% of the stomach adenocarcinomas (5 studies; 739 samples) and 18% of these cancers harbor the p.(His1047Arg) missense variant [15, 16]. We investigated the frequency of PIK3CA c.3140A>G p.(His1047Arg) in population datasets not enriched for tumor associated phenotypes. The variant was not found in >13,000 individuals with WES data (inhouse database) or in >2,000 individuals from other (non-cancer) SOLVE-RD cohorts. PIK3CA c.3140A>G was only detected in 1 out of >120,000 gnomAD individuals. While little details are available, the variant was identified in a female non-Finnish European aged 35–40 years, at a VAF of 25–30%, also suggestive of somatic mosaicism [17]. Interestingly, the germline WES data from this female originated from The Cancer Genome Atlas, indicating that this individual too developed cancer at a young age (≤40 years).

Discussion

In this study, we present the case of a woman with early-onset DGC in whom neither targeted CDH1 and CTNNA1 variant screening, nor a previous WES analysis provided a genetic diagnosis. Re-analysis of the WES data revealed a mosaic PIK3CA c.3140A>G p.(His1047Arg) variant, suggestive of a potential role in the patient’s phenotype and early-onset of diffuse type gastric cancer.

Mosaic PIK3CA variants have been described in PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (PROS), syndromes marked by congenital or early-onset of sporadic segmental tissue overgrowth, vascular malformations and mosaic skin lesions [18]. A constitutional heterozygous Pik3caH1047R murine model is embryonically lethal [19], an observation that is consistent with the mosaic status of PIK3CA in PROS and in gnomAD. For PIK3CA somatic mosaicism, the timing and location when a PIK3CA is variant introduced during postzygotic development likely determines the phenotypic presentation of malignancies [13]. For PROS it is reported that mosaic PIK3CA variants arise in ectodermal and mesodermal tissues, whereas the digestive tract, including the stomach, arises from endoderm. Since no clear signs of overgrowth or dysmorphologies were observed, but the variant is detected in leukocyte-derived DNA, the variant may be present in the endoderm and mesoderm layer only. The mosaic state of the variant could be the result of a postzygotic introduction of the variant in the mesendoderm layer [20]. Blood used in the genetic analyses in this study was obtained before chemotherapy, which rules out a scenario of clonal expansion of the variant due to the selective pressure of chemotherapeutic agents.

The initial WES analysis, described by Vogelaar et al., was directed towards the identification of rare high-confidence nonsynonymous germline variants (≥20% variant reads) in known hereditary cancer genes or genes involved in GC development. This approach reduces the chance of identification of mosaicism, as these variants often do not meet the quality threshold of ≥20% variant reads [11]. By decreasing the VAF cut-off, in combination with ClinVar assessment, mosaic disease-causing variants associated with impaired protein function can be identified, a strategy that is not widely applied to WES and WGS studies. However, WES/WGS data alone is not sufficient to confirm etiology, and further evidence for pathogenicity, using a multifactorial approach and other tissue sources is critical for this. Unfortunately, due to the historical age of the case, no additional (tumor) tissue samples could be obtained from the patient to demonstrate the presence of the variant in tissues derived from different embryonic layers and the neoplastic cells of the gastric tumor.

To our knowledge, there is no literature describing mosaic PIK3CA variants in association with DGC. Within the field of unresolved rare disorders, the identification of causative variants and molecular diagnosis is challenging, as an obvious the genotype-phenotype often cannot be found. However, a similar case of early-onset cancer in combination with a mosaic PIK3CA variant is reported in the gnomAD-TCGA database, supporting the increased cancer risk associated with mosaicism for this variant. Our finding suggests that mosaic predisposing variants are potentially understudied in individuals suspected of having a genetic tumor risk syndrome. As such, it will be of interest to investigate the prevalence of mosaic PIK3CA variants in DGC and other cancers diagnosed in young adults. Detection of mosaicism has implications for relatives as well. As heterozygosity for PIK3CA c.3140A>G is considered lethal, relatives do most probably not have an increased risk for cancer.

To conclude, further studies are needed to confirm the potential role of PIK3CA mosaicism in cancer susceptibility. However, this report demonstrates the success of an improved approach for (mosaic) variant discovery. The reported diagnostic value of exome re-analysis should stimulate the field to re-analyze exome data of genetically undiagnosed genetic tumor risk syndrome patients by similar approaches. Furthermore, this report underlines the complexity that rare disease patients may face awaiting their genetic diagnosis. For many disease genes we may not yet know the full phenotypic presentation, which is especially challenging in genes like PIK3CA, where the presentation of the clinical phenotype is dependent on the timing of the postzygotic event.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank SOLVE-RD for the infrastructure and in-depth discussions on strategies for the re-analyses of genomic data for disease gene identification. This research is supported (not financially) by the European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes (ERN GENTURIS)—Project ID No 739547. ERN GENTURIS is partly co-funded by the European Union within the framework of the Third Health Programme ERN-2016—Framework Partnership Agreement 2017–2021.

Solve-RD-GENTURIS group

Laura Valle11, Gabriel Capella11, Stefan Aretz5, Elke Holinski-Feder12, Verena Steinke-Lange12, Andreas Laner12, Evelin Schröck13, Andreas Rump13, Marjolijn Ligtenberg14, Alexander Hoischen15, Nicoline Geverink16, D. Gareth Evans17, Marc Tischkowitz18, Steven Laurie19

Funding

The Solve-RD project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 779257. The research work at i3S/Ipatimup is supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through COMPETE 2020 - Operacional Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation (POCI), Portugal 2020, and by Portuguese funds through FCT/ Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação in the framework of the project “Institute for Research and Innovation in Health Sciences” (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007274) and Project Ref. POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030164. Data was reanalysed using the RD‐Connect Genome‐Phenome Analysis Platform, which received funding from EU projects RD‐Connect, Solve-RD and EJP-RD (grant numbers FP7 305444, H2020 779257, H2020 825575), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant numbers PT13/0001/0044, PT17/0009/0019; Instituto Nacional de Bioinformática, INB) and ELIXIR Implementation Studies.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Members of the Solve-RD-GENTURIS group are listed below Acknowledgements.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Richarda M. de Voer, Email: Richarda.devoer@radboudumc.nl

Solve-RD-GENTURIS group,:

Laura Valle, Gabriel Capella, Stefan Aretz, Elke Holinski-Feder, Verena Steinke-Lange, Andreas Laner, Evelin Schröck, Andreas Rump, Marjolijn Ligtenberg, Alexander Hoischen, Nicoline Geverink, D. Gareth Evans, Marc Tischkowitz, and Steven Laurie

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41431-021-00853-6.

References

- 1.van der Post RS, Oliveira C, Guilford P, Carneiro F. Hereditary gastric cancer: what’s new? Update 2013-2018. Fam Cancer. 2019;18:363–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-019-00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–5. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worthley DL, Phillips KD, Wayte N, Schrader KA, Healey S, Kaurah P, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): a new autosomal dominant syndrome. Gut. 2012;61:774–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira C, Senz J, Kaurah P, Pinheiro H, Sanges R, Haegert A, et al. Germline CDH1 deletions in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1545–55. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majewski IJ, Kluijt I, Cats A, Scerri TS, de Jong D, Kluin RJ, et al. An alpha-E-catenin (CTNNA1) mutation in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2013;229:621–9. doi: 10.1002/path.4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fewings E, Larionov A, Redman J, Goldgraben MA, Scarth J, Richardson S, et al. Germline pathogenic variants in PALB2 and other cancer-predisposing genes in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer without CDH1 mutation: a whole-exome sequencing study. Lancet. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:489–98. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30079-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogelaar IP, Ligtenberg MJ, van der Post RS, de Voer RM, Kets CM, Jansen TJ, et al. Recurrent candidiasis and early-onset gastric cancer in a patient with a genetically defined partial MYD88 defect. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:289–96. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9859-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matalonga L, Hernández-Ferrer C, Piscia D, Group S-RS-iw, Vissers LELM, Schüle R, et al. Solving patients with rare diseases through programmatic reanalysis of genome-phenome data. EJHG. 2021. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Steeghs EMP, Kroeze LI, Tops BBJ, van Kempen LC, Ter Elst A, Kastner-van Raaij AWM, et al. Comprehensive routine diagnostic screening to identify predictive mutations, gene amplifications, and microsatellite instability in FFPE tumor material. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:291. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06785-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair VR, McLeod M, Carneiro F, Coit DG, D’Addario JL, van Dieren JM, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical practice guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e386–e97. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelaar IP, van der Post RS, van Krieken JHJ, Spruijt L, van Zelst-Stams WA, Kets CM, et al. Unraveling genetic predisposition to familial or early onset gastric cancer using germline whole-exome sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:1246–52. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orloff MS, He X, Peterson C, Chen F, Chen JL, Mester JL, et al. Germline PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations in Cowden and Cowden-like syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madsen RR, Vanhaesebroeck B, Semple RK. Cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations in overgrowth disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:856–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alfoldi J, Wang Q, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–43. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuentz P, St-Onge J, Duffourd Y, Courcet JB, Carmignac V, Jouan T, et al. Molecular diagnosis of PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) in 162 patients and recommendations for genetic testing. Genet Med. 2017;19:989–97. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hare LM, Schwarz Q, Wiszniak S, Gurung R, Montgomery KG, Mitchell CA, et al. Heterozygous expression of the oncogenic Pik3ca(H1047R) mutation during murine development results in fatal embryonic and extraembryonic defects. Dev Biol. 2015;404:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tada S, Era T, Furusawa C, Sakurai H, Nishikawa S, Kinoshita M, et al. Characterization of mesendoderm: a diverging point of the definitive endoderm and mesoderm in embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Development. 2005;132:4363–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.02005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.