Abstract

Access to energy is an important social determinant of health, and expanding the availability of affordable, clean energy is one of the Sustainable Development Goals. It has been argued that climate mitigation policies can, if well-designed in response to contextual factors, also achieve environmental, economic, and social progress, but otherwise pose risks to economic inequity generally and health inequity specifically. Decisions around such policies are hampered by data gaps, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and among vulnerable populations in high-income countries (HICs). The rise of “big data” offers the potential to address some of these gaps. This scoping review sought to explore the literature linking energy, big data, health, and decision-making.

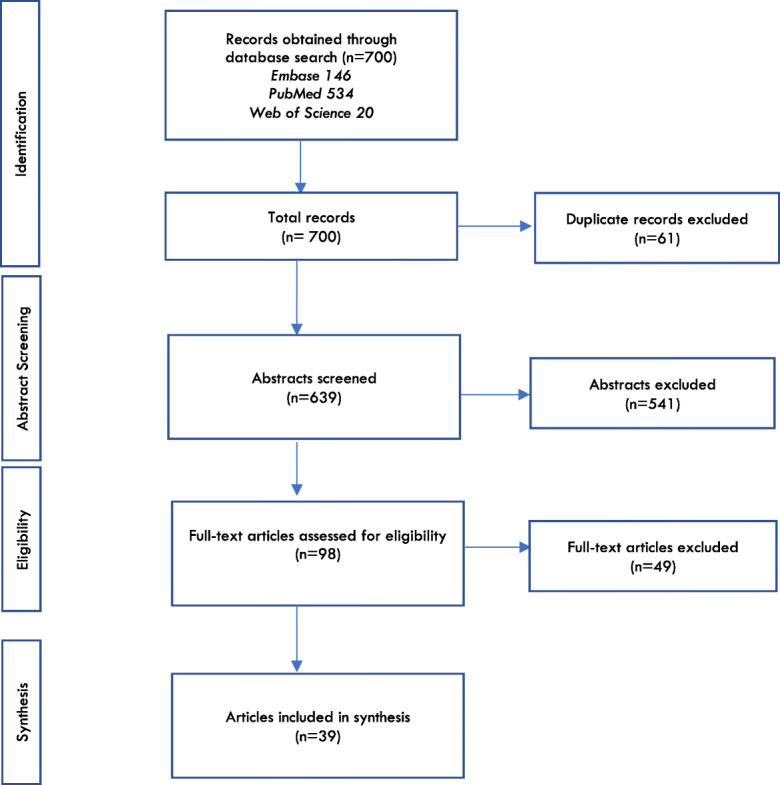

Literature searches in PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were conducted. English language articles up to April 1, 2020, were included. Pre-agreed study characteristics including geographic location, data collected, and study design were extracted and presented descriptively, and a qualitative thematic analysis was performed on the articles using NVivo.

Thirty-nine articles fulfilled eligibility criteria. These included a combination of review articles and research articles using primary or secondary data sources. The articles described health and economic effects of a wide range of energy types and uses, and attempted to model effects of a range of technological and policy innovations, in a variety of geographic contexts. Key themes identified in our analysis included the link between energy consumption and economic development, the role of inequality in understanding and predicting harms and benefits associated with energy production and use, the lack of available data on LMICs in general, and on the local contexts within them in particular. Examples of using “big data,” and areas in which the articles themselves described challenges with data limitations, were identified.

The findings of this scoping review demonstrate the challenges decision-makers face in achieving energy efficiency gains and reducing emissions, while avoiding the exacerbation of existing inequities. Understanding how to maximize gains in energy efficiency and uptake of new technologies requires a deeper understanding of how work and life is shaped by socioeconomic inequalities between and within countries. This is particularly the case for LMICs and in local contexts where few data are currently available, and for whom existing evidence may not be directly applicable. Big data approaches may offer some value in tracking the uptake of new approaches, provide greater data granularity, and help compensate for evidence gaps in low resource settings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11524-021-00563-w.

Keywords: Energy, Inequity, Data, Public health, Global health, Policy

Introduction

Energy usage has been central to human society from its earliest history and is associated with many health benefits through the production of goods and services, transportation, housing, protection from extremes of heat and cold, communications, science and technology, overall increases in economic productivity, and even public safety [1]. Access to energy is regarded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an important social determinant of health [2], and expanding the availability of affordable, clean energy is one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). An estimated 3 billion people still lack access to clean cooking fuels and technology, and 840 million people live without electricity [3]. In parallel, the global challenge of climate change has highlighted the importance of reducing emissions, and inherent in them, the inequalities associated with energy globally, including inequalities in the harm generated through energy production, and in efficiency and consumption levels within and between countries.

Climate change itself has been observed to exacerbate global economic inequality [4], with vulnerable populations and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) disproportionately exposed to extreme weather events, sea-level rises, increased risk of infectious diseases, and food insecurity [5]. Following the science to tackle climate change will require difficult decisions at local, national, and international levels, and likely profound societal changes. These decisions may risk exacerbating existing inequities by preventing affordable energy access to those for whom this is an important health and developmental need, or by transitioning economic activity in ways that disproportionately disadvantages those with more limited wealth, education, and social capital [6–8]. Growing inequity, either due to the worsening effects of climate change or the consequences of climate change mitigation efforts, risks widening attendant health gaps [5, 8].

It has been argued that climate change mitigation policies can, if well-designed in response to contextual factors, achieve environmental, economic, and social progress, but otherwise pose risks to inequality generally and health inequities specifically [9]. The 2020 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Climate Change called for a high priority to be set on further understanding which populations are vulnerable to climate change, the health and environmental consequences of inaction, and potential side-effects of required mitigation efforts [5].

In to that improve public support for these measures, and mitigate their effects on health inequalities, it is important that decision-makers are aware of the role of energy as a social determinant of health, both in the context of its production and its consumption. It has been argued that one way in which upstream determinants of health such as energy production and use can better inform decision-making is through expanding use of “big data” approaches [10]. However, little is currently known about the extent to which such approaches have been applied to energy as a determinant of health and to what extent this has featured in decision-making.

We report the findings of a scoping review that sought to address this gap by identifying and describing the available literature explicitly or implicitly linking energy—including energy production, consumption, conservation, and pollution—with use of data, and the implications for decision-making.

Methodology

Search Strategy

The search strategy was formulated by an experienced Boston University librarian and revised and finalized by a three-person research team (2 researchers GR and SFK, 1 supervisor SMA). All articles available in Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science as of April 1, 2020, uncovered through our search strategy were initially considered.

In Embase, three separate searches returned articles with titles, abstracts, or author keywords (ti,ab,kw) related to data, decision-making, and energy, respectively. These searches were combined resulting in 146 articles. In PubMed, two searches were combined. The first search identified 387 articles related to decision-making, health, and energy based on MeSH Terms and text words ([tw]). The second search identified 147 articles related to energy, decision-making, and data based on MeSH Terms and text words ([tw]). The search field tag [tw] was used to enhance the search strategy; [tw] generated results by searching titles, abstracts, other abstracts, MeSH Terms, MeSH Subheadings, Publication Types, Comment/Correction Notes, non-MeSH Subject Terms (keywords), and other Terms field (including author-supplied keywords). In total, 534 articles were returned from PubMed. In Web of Science, three separate searches returned articles with titles (TI) related to data, decision-making, and energy, respectively. These search results were combined, returning a total 20 articles from Web of Science.

The full search strings for Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science can be found in the Appendix. Articles written in a language other than English, conference proceedings and abstracts, and general reports were excluded.

Screening and Selection of Articles

One researcher (GR) downloaded the 700 articles identified across Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science to the citation manager Zotero [11] and then uploaded the articles to Rayyan, a web application for collaborative systematic reviews developed by Hamad Bin Khalifa University and Qatar computing research institute [12].

Two researchers (GR and SFK) independently used this software to identify and remove 61 duplicates, leaving 639 articles. These abstracts then underwent independent, blinded abstract screening. Two researchers (GR and SFK) used Rayyan to record and indicate their justification for including or excluding articles in the abstract screening stage. Discrepancies were addressed as they emerged through discussion between the researchers (GR and SFK), and disagreements were resolved by supervisor (SMA). Five hundred forty-one articles were excluded, leaving 98 articles which underwent independent and blinded full-text eligibility assessment. The articles were transferred from Rayyan to Excel, and justifications for inclusion and exclusion were noted, with discrepancies subsequently addressed through discussion between researchers (GR and SFK), and disagreements were resolved by supervisor (SMA). Forty-nine articles were excluded through this process, leaving 39 articles eligible for the final synthesis stage.

Analysis

We used a “descriptive-analytical” method within the narrative tradition, as proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [13], presenting our findings in the form of a descriptive numerical summary and including a qualitative thematic analysis as recommended by Levac et al. [14]. For the numerical summary, a common framework was applied for all the papers included to collect standard information on key issues and themes around energy, data, and decision-making. Both researchers (GR and SFK) involved in article screening used the framework independently to review articles apiece in Excel. The two Excel files were later merged and finalized.

The qualitative thematic analysis was performed by an experienced qualitative researcher (NM) (separate to those involved in the abstract and full-text screening steps) who read and iteratively coded [15] all articles using NVivo (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12).

Results

After screening 639 titles and abstracts and 98 full text articles, 39 unique articles were included in this review (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of articles assessed through the different phases of the review

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| First author | Year | Location | Data | Study design | Energy, data, health, decision-making |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mardani | 2019 | Varies | Varies (review) | Systematic review | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Markandya | 2009 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Torres-Duque | 2008 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Review in service of report | Energy, health |

| Chen | 2007 | Shanghai, China | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, data, health, decision-making |

| Courtemanche | 2011 | USA | Secondary | Retrospective and prospective modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Lin | 2019 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Retrospective and prospective modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Chio | 2019 | Taiwan | Secondary | Prospective modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Davis | 1997 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, data, health, decision-making |

| Dockery | 2013 | Ireland | Primary/secondary | Longitudinal cohort study/report | Energy, health |

| Nanaki | 2015 | Greece | Secondary | Cost/benefit analysis and total cost of ownership | Energy, health, data, decision-making |

| Xiao | 2006 | Hong Kong and China | Secondary | Comparative modeling and economic valuation | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Kan | 2012 | China | Secondary | Systematic review | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Staff Mestl | 2007 | China | Secondary | Exposure assessment | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Kyu | 2010 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Cai | 2013 | Beijing | Primary/secondary | Predictive modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Spitzer | 1996 | USA | Secondary | Comparative modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Partridge | 2012 | China | Secondary | Comparative modeling and comparative cost/benefit analysis | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Hays | 2016 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Varying designs | Energy, health |

| Li | 2003 | Shanghai, China | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, data, health, decision-making |

| Gohlke | 2011 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Comparative predictive modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Aunat | 1998 | Hungary | Secondary | Cost/benefit analysis | Energy, health, decision-making |

| De Salvo | 2014 | New Orleans, Louisiana, USA | Primary | Cross-sectional | Data, energy, health, decision-making |

| Chestnut | 2005 | USA | Secondary | Cost/benefit analysis | Energy, health, decision-making |

| He | 2017 | China | Secondary | Panel data analysis | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Bell | 2006 | Mexico, Chile, and Brazil | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Data, energy, health, decision-making |

| Marcus | 2017 | California, USA | Secondary | Cohort study | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Sofiev | 2018 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Comparative prospective modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Liu | 2020 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Panel data analysis | Data, energy |

| Qomi | 2016 | Cambridge, USA | Secondary | Spatial analysis and modeling | Energy, health, data, decision-making |

| Scovronick | 2016 | São Paulo State, Brazil | Secondary | Comparative modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Perera | 2019 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Case-control, cohort studies, and meta-analyses | Energy, health |

| Wang | 2010 | Taiwan | Secondary | Ecological study | Energy, data, health |

| Georges | 2007 | São Paulo, Brazil | Secondary | Mixed methods | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Bonjour | 2013 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, data |

| Penn | 2017 | Continental USA | Secondary | Modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

| Wu | 2010 | Taiwan | Secondary | Mixed methods | Data, energy, decision-making |

| Winebrake | 2009 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, health, data, decision-making |

| 2019 | More than 5 countries | Secondary | Cross-sectional | Energy, data, health | |

| Guo | 2018 | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China | Secondary | Prospective modeling | Energy, health, decision-making |

Topics Covered

The articles identified in this review attempted to estimate the health and economic effects of a range of different energy generation types, energy uses, and emission reduction approaches, such as changes to fuel composition in ships [16, 17] and cars [18, 19], oil price changes [20], transport electrification [21, 22], environmental standards [23], coal power plants [24, 25], and cooking fuels [26, 27]. In doing so, authors examined the health benefits of increasing efficiency and reducing pollution [16, 18, 28–31], and how improvements in pollution control might affect these outcomes [16, 17, 19]. In some articles, this included estimating the non-health benefits of increased energy efficiency and reducing pollution, including cost reductions for consumers [21, 23], improvements to the physical environment [23, 32], economic benefits [32], increased productivity [23], and national security [31, 33]. In others, this included estimating the non-health harms of pollution, such as crop loss [31], and the eutrophication of coastal waters [23].

Several key themes were identified in our analysis of these articles in the intersection of energy, data, and decision-making. These included the relationship between energy consumption and economic development, and linked to this theme, a clear needs to understand the role of inequality in understanding and predicting harms and benefits associated with energy production and use in more granular and nuanced ways. Relatedly, the limitations and foci of these studies emphasize the importance of understanding local contexts and microenvironments in decision-making, be that in reducing health inequities, or monitoring uptake of new approaches and technologies. Through these studies, examples of the potential value of applying “big data” approaches to overcome these challenges were identified, along with areas in which the articles themselves identified a need for more granular data. We expand on each theme below.

Energy and National Economic Development

Energy is an important pillar of economic growth, and the link between CO2 emissions and globalization was described as an inverted U shape, in which countries emissions increased with economic development before declining due to greater environmental awareness, cultural exchange, and improvements in fuel efficiency [34]. By contrast, economic recession was noted to have a retarding effect on the pace of improvements in efficiency [31]. Greater energy usage was associated with improvements in infant mortality in countries with a high baseline infant mortality rate and low life expectancy. However, based on time series data from 41 countries, these health benefits exhibited diminishing returns, and in countries with infant mortality less than 100/1,000 live births, benefits were not observed [35]. At the national level, these correlations reflect the links between economic development, energy use, and health, and the particular needs and exigencies facing developing economies.

Relatedly, as economies change emphasis over time, patterns of energy generation and use, and therefore exposures to environmental pollution, also shift. For example, in Western Europe during the late 1980s and early 1990s, industry emissions declined but were offset by increases in private car and motorbike ownership, even as gross domestic product (GDP) declined [31]. In LMICs, smoke produced during the burning of biofuels remains a significant contributor to poorer health for children and adults [27]. In these settings, economic status is a pivotal factor in a family’s ability to choose to use more expensive but cleaner and less health-harming fuels, described as moving up the household “energy ladder” [36]. This represents one example of the links between energy and inequality both between and within countries. This is a critical consideration for decision-makers seeking to balance improvements in health through economic progress in LMICs on the one hand, and reductions in emissions and other harms associated with greater energy production on the other.

Energy and Social Inequality

Social inequality emerged from the review as a critical consideration in how energy constitutes a determinant of health. Benefits to improvements in energy efficiency and developments towards healthier types of energy generation in general are often patterned unequally between and within countries, with the greatest harm, both in terms of energy production, and consumption patterns, accruing to those of lower socioeconomic status. For example, at the global level, the proportion of households using solid fuels for cooking declined between 1980 and 2010. However, because of population growth, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia, the absolute number of persons using such fuels, and therefore being exposed to indoor air pollution, has remained fairly constant, according to multi-level modeling of national survey data [26]. Exposure to environmental pollution caused by energy production is strongly correlated with geographic location. For example, communities in close proximity to roads [37], or in large urban centers [25, 32, 38], face much higher levels of particulate matter. Coastal communities are more susceptible to pollution by shipping traffic [16, 17], and agricultural and shipping pollutants combine to disrupt local coastal ecosystems and food supplies with economic and health implications that disproportionately affect those who can least afford to migrate inland and are most reliant on locally produced food [16, 17, 23, 39].

The studies identified also show how risks from pollution were patterned in intersectional ways in the context of age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Those with a lower than high school education in China faced greater relative risk of poor health effects from air pollution [38], and women, children, and the elderly were identified as particularly vulnerable [37, 38]. Children have higher baseline ventilation rates, and spend more time outdoors engaged in physical activity than adults, and are thus overexposed to pollution hazards [37].

Women and children in low-income settings are also disproportionately exposed to pollution due to proximity to household cooking and heating fuels during use [27], with such effects exacerbated by poor ventilation. The use of such energy sources is associated with other harms often not included in attempts to model burden of disease from indoor air pollution. For example, the use of such methods in cramped conditions is likely to increase the risk of burns and scalds [26]. The need to seek such fuels, typically by women, combined with poor infrastructure, street lighting, and public safety, leads to an increased risk of experiencing violence [26]. These studies provide examples of the ways in which understanding local exposures, activity patterns and contexts, particularly in low-income settings, and among vulnerable populations, is a critical, technically challenging aspect of modeling the effects of energy use and pollution.

Local Contexts and Microenvironments

A key theme from our review of these studies is the importance of understanding local context and microenvironments in determining the harms associated with energy production and the benefits associated with its use, even though such data are often lacking. Pollution is typically highly geographically patterned, and this characteristic is acknowledged in modeling studies that seek to assess the effects of such pollution, or the likely health improvements associated with reductions in emissions. This is particularly important in the context of urban environments, as they can combine high levels of pollution with high numbers of people exposed [18, 30, 40]. A modeling study found that the health effects of coal powerplants were highly patterned, with New Taipei City, Taipei City, and Taoyuan City alone estimated to account for 68.3% of all pre-mature deaths attributable to PM2.5 in Taiwan [25].

The importance of local context is especially relevant in the context of understanding effects on particularly vulnerable populations. However, much of the original research used to model air pollution mortality harms and benefits is from high-income country (HICs) settings, and so may not reflect the combination of pollutants and other environmental factors arising from energy use and expenditure in lower income settings. These include the role of indoor air pollution [41] or building design differences, such as level of ventilation, height of chimneys, or the health harms associated with specific combinations of atmospheric variables and particulate types.

Beyond modeling challenges, socioeconomic inequality imposes a triple burden and obstructs improvements in emissions and health overall. First, lower socioeconomic status has a constraining effect on the ability to take up more modern, more efficient, and less polluting energy uses, to adapt to energy price changes, or to mitigate extreme exposures through ventilation or air-conditioning. Second, lower socioeconomic status has an overexposing effect in terms of more direct exposure to environmental pollution through patterns of work and daily life for both adults and children. Third, these exposures pattern onto existing inequality along other dimensions, such as access to nutrition, clean water, education, and safe home and work environments that contribute to poorer baseline health and shorter life expectancy, and make these groups more vulnerable to pollution and its consequences [42].

Local context and microenvironments are therefore critical in understanding the mediating pathways by which this burden is perpetuated, and ensuring these are encompassed in data collection and modeling studies that can inform decision-making.

Examples of Big Data Utilization

“Big data” are broadly defined as “digital data of high volume, velocity, and variety passively derived from everyday interactions with digital products or services, including mobile phones, credit cards, and social media” that “require new tools and methods to capture, curate, manage, and process” [43, 44]. The rise of “big data” approaches offers the possibility of improving the granularity of our understanding of local variations in energy use and exposure to energy-related pollution, particularly where data have traditionally been lacking. The rise of “big data” may also aid our understanding of trends in human activity over time, such as uptake of new technologies, travel, and exposure patterns.

Studies included in this review demonstrate the value of big data in identifying vulnerable populations. An analysis of Medicare data in New Orleans, USA, allowed for the identification of individuals especially vulnerable to power outages due to reliance on home ventilator use [45]. Another study used a data analytics approach combining building footprint, gas bills, and climate data in Cambridge, USA, to identify the most efficient type and number of buildings town planners might prioritize for retrofitting [46]. Cai et al. used a data mining approach to individual travel patterns to identify the most common taxi trajectories in Beijing and estimate real-world implications of fleet electrification, and the most cost-effective incentives for plug-in hybrid vehicles [21]. In doing so, this approach helps overcome challenges in estimating common vehicle travel patterns, which can often vary widely by local region [20]. Through the use of high-resolution data from the ship-based Automatic Identification System, in combination with atmospheric model and health risk functions, Sofiev et al. were able to improve the geospatial resolution of ship pollution-related health effects globally and identify those regions likely to experience the largest mortality and morbidity benefits [16].

Challenges That Could Be Overcome through Using Big Data

The studies in this review also highlighted the challenges to be overcome in order to improve the use of big data in energy and decision-making around health. These include the need for better data on the complex interplay between energy affordability and health, particularly for disadvantaged groups, as well as the role of waste products other than air emissions, which may become increasingly prominent as new technologies proliferate [29]. As patterns of activity change in heterogeneous ways over time in response to technological and economic changes, particularly in countries with fast-growing economies, so too does the distribution and nature of pollutants such as sulfur dioxide and volatile organic compounds. These require better monitoring data both in relation to emissions, and in relation to activity patterns, and a greater understanding of the local contexts in which they occur [47], all of which big data could help inform. The use of state or even countywide estimates of population density and health status in countries such as the USA [48], while helpful, likely masks the health damage accruing to local populations that are disproportionately vulnerable due to their physical and social microenvironments. These types of data, including the proportion of citizens living in poverty, are at times not known and therefore not included in modeling estimates [49].

Beyond providing greater data granularity focused solely on exposure or activity, big data may help address challenges along the causal chain between energy generation and health outcomes [50]. This could include providing data on the extent to which new regulations are implemented, the type and nature of emissions in a greater range of locations, levels of ambient air quality, personal and population-level exposures to pollutants, and the extent to which mitigating actions are implemented in ways that minimize harm to those most at risk.

Priorities for Further Research

There are limitations as to how big data approaches could resolve these issues. Many of these challenges require a more conscious prioritization of data collection and research rather than use of existing data repositories. Part of the challenge inherent in several of the studies in this review was the use of exposure-response functions based primarily on US and Western European populations [51], highlighting a need for greater data granularity at the global level to better inform modeling of air pollution and climate change impacts. Critically, in many contexts, the local conditions in LMICs, including the physical and chemical nature of pollutants, their distribution, and the activities of local populations, including health behaviors such as smoking or physical activity, may differ significantly from HIC counterparts [38, 42, 51–53].

Even in HICs, while childhood diseases associated with air pollution were included in studies assessing health impacts, the life-course effects of air pollution and other environmental exposures in energy generation on children in particular were usually not considered [36]. This is concerning as this exposure and therefore effect, may be highest in those contexts for which data is most lacking, and such consequences may represent a significant fraction of overall health and economic harms in the longer term.

Conclusions

This scoping review identified a number of ways in which big data approaches might help to inform decision-making in the context of energy as a determinant of health. It is clear that big data may be able to bridge gaps in understanding and predicting the localized harms and benefits associated with energy production and use. It is also clear that significant data gaps remain, especially in understanding and predicting changes in energy generation and use in LMICs.

This scoping review identifies some of the ways in which there is a need to make data and evidence regarding energy use and pollution widely available to better reflect and serve diverse global contexts. Expanding the use of big data, including those data made available through private providers, could better help decision-makers at global, national, and local levels better determine the nature of their energy challenges, and inform decisions about the most feasible and cost-effective courses of action in mitigating health effects for the most vulnerable.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 42 kb)

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nason Maani, Email: nmaanihe@bu.edu.

Grace Robbins, Email: grobbins@bu.edu.

Shaffi Fazaludeen Koya, Email: fmshaffi@bu.edu.

Opeyemi Babajide, Email: opeyemilatona@gmail.com.

Salma M Abdalla, Email: abdallas@bu.edu.

Sandro Galea, Email: sgalea@bu.edu.

References

- 1.Smith KR, Frumkin H, Balakrishnan K, Butler CD, Chafe ZA, Fairlie I, Kinney P, Kjellstrom T, Mauzerall DL, McKone TE, McMichael AJ, Schneider M. Energy and human health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34(1):159–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Energy: shared interests in sustainable development and energy services. Geneva: World Health Organization;2013.

- 3.United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals overview. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/overview/. Published 2020. Accessed 1/14/2021, 2020.

- 4.Diffenbaugh NS, Burke M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(20):9808–9813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Beagley J, Belesova K, Boykoff M, Byass P, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, Chambers J, Coleman S, Dalin C, Daly M, Dasandi N, Dasgupta S, Davies M, di Napoli C, Dominguez-Salas P, Drummond P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Georgeson L, Golder S, Grace D, Graham H, Haggar P, Hamilton I, Hartinger S, Hess J, Hsu SC, Hughes N, Jankin Mikhaylov S, Jimenez MP, Kelman I, Kennard H, Kiesewetter G, Kinney PL, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lampard P, Lemke B, Liu Y, Liu Z, Lott M, Lowe R, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McGushin A, McMichael C, Milner J, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Munzert S, Murray KA, Neville T, Nilsson M, Sewe MO, Oreszczyn T, Otto M, Owfi F, Pearman O, Pencheon D, Quinn R, Rabbaniha M, Robinson E, Rocklöv J, Romanello M, Semenza JC, Sherman J, Shi L, Springmann M, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Triñanes J, Shumake-Guillemot J, Vu B, Wilkinson P, Winning M, Gong P, Montgomery H, Costello A. The 2020 report of The <em>Lancet</em> Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):129–170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan U, Zhang Y. The global inequalities and climate change. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rao ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. WIREs Climate Change. 2018;9(2):e513. doi: 10.1002/wcc.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessel S, Sawyer S, Hernández D. Energy, poverty, and health in climate change: a comprehensive review of an emerging literature. Front Public Health. 2019;7:357. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markkanen S, Anger-Kraavi A. Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality. Clim Pol. 2019;19(7):827–844. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2019.1596873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea S, Abdalla SM, Sturchio JL. Social determinants of health, data science, and decision-making: Forging a transdisciplinary synthesis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(6):e1003174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coar JT, Sewell JP. Zotero: harnessing the power of a personal bibliographic manager. Nurse Educ. 2010;35(5):205–207. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181ed81e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Research Methodology, Theory and Practice. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;20:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sofiev M, Winebrake JJ, Johansson L, Carr EW, Prank M, Soares J, Vira J, Kouznetsov R, Jalkanen JP, Corbett JJ. Cleaner fuels for ships provide public health benefits with climate tradeoffs. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02774-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winebrake JJ, Corbett JJ, Green EH, Lauer A, Eyring V. Mitigating the health impacts of pollution from oceangoing shipping: an assessment of low-sulfur fuel mandates. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(13):4776–4782. doi: 10.1021/es803224q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scovronick N, França D, Alonso M, et al. Air quality and health impacts of future ethanol production and use in São Paulo State, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Spitzer HL. An analysis of the health benefits associated with the use of MTBE reformulated gasoline and oxygenated fuels in reducing atmospheric concentrations of selected volatile organic compounds. Risk Anal. 1997;17(6):683–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1997.tb01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He L-Y, Yang S, Chang D. Oil price uncertainty, transport fuel demand and public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):245. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai H, Xu M. Greenhouse gas implications of fleet electrification based on big data-informed individual travel patterns. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(16):9035–9043. doi: 10.1021/es401008f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanaki EA, Xydis GA, Koroneos CJ. Electric vehicle deployment in urban areas. Indoor and Built Environment. 2016;25(7):1065–1074. doi: 10.1177/1420326X15623078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chestnut LG, Mills DM. A fresh look at the benefits and costs of the US acid rain program. J Environ Manag. 2005;77(3):252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CK, Lin RT, Chen T, Zigler C, Wei Y, Christiani DC. A global perspective on coal-fired power plants and burden of lung cancer. Environ Health. 2019;18(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12940-019-0448-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chio CP, Lo WC, Tsuang BJ, Hu CC, Ku KC, Chen YJ, Lin HH, Chan CC. Health impact assessment of PM(2.5) from a planned coal-fired power plant in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(11):1494–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonjour S, Adair-Rohani H, Wolf J, Bruce NG, Mehta S, Prüss-Ustün A, Lahiff M, Rehfuess EA, Mishra V, Smith KR. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980-2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(7):784–790. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyu HH, Georgiades K, Boyle MH. Biofuel smoke and child anemia in 29 developing countries: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(11):811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu W-T, Tsai P-J, Yang Y-H, Yang C-Y, Cheng K-F, Wu T-N. Health impacts associated with the implementation of a national petrol-lead phase-out program (PLPOP): evidence from Taiwan between 1981 and 2007. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(5):863–867. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markandya A, Armstrong BG, Hales S, Chiabai A, Criqui P, Mima S, Tonne C, Wilkinson P. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: low-carbon electricity generation. Lancet. 2009;374(9706):2006–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao F, Brajer V, Mead RW. Blowing in the wind: the impact of China’s Pearl River Delta on Hong Kong’s air quality. Sci Total Environ. 2006;367(1):96–111. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aunan K, Pátzay G, Asbjørn Aaheim H, Martin SH. Health and environmental benefits from air pollution reductions in Hungary. Sci Total Environ. 1998;212(2-3):245–268. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo X, Zhao L, Chen D, Jia Y, Zhao N, Liu W, Cheng S. Air quality improvement and health benefit of PM(2.5) reduction from the coal cap policy in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(32):32709–32720. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtemanche C. A silver lining? The connection between gasoline prices and obesity. Econ Inq. 2011;49(3):935–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2009.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M, Ren X, Cheng C, Wang Z. The role of globalization in CO2 emissions: a semi-parametric panel data analysis for G7. Sci Total Environ. 2020;718:137379. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gohlke JM, Thomas R, Woodward A, Campbell-Lendrum D, Prüss-Üstün A, Hales S, Portier CJ. Estimating the global public health implications of electricity and coal consumption. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(6):821–826. doi: 10.1289/ehp.119-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres-Duque C, Maldonado D, Pérez-Padilla R, Ezzati M, Viegi G. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidence. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(5):577–590. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-100RP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcus M. On the road to recovery: gasoline content regulations and child health. J Health Econ. 2017;54:98–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kan H, Chen R, Tong S. Ambient air pollution, climate change, and population health in China. Environ Int. 2012;42:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mbow C, Rosenzweig C, Barioni LG, Benton TG, Herrero M, Krishnapillai M, Liwenga E, Pradhan P, Rivera-Ferre MG, Sapkota T, Tubiello FN, Xu Y Food Security. In: Climate Change and Land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems International Panel on Climate Change; 2019.

- 40.Li J, Guttikunda SK, Carmichael GR, Streets DG, Chang Y-S, Fung V. Quantifying the human health benefits of curbing air pollution in Shanghai. J Environ Manag. 2004;70(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abdollahpour I, Abdulkader RS, Abebe HT, Abebe M, Abebe Z, Abejie AN, Abera SF, Abil OZ, Abraha HN, Abrham AR, Abu-Raddad LJ, Accrombessi MMK, Acharya D, Adamu AA, Adebayo OM, Adedoyin RA, Adekanmbi V, Adetokunboh OO, Adhena BM, Adib MG, Admasie A, Afshin A, Agarwal G, Agesa KM, Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Ahmadi A, Ahmadi M, Ahmed MB, Ahmed S, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aichour MTE, Akbari ME, Akinyemi RO, Akseer N, al-Aly Z, al-Eyadhy A, al-Raddadi RM, Alahdab F, Alam K, Alam T, Alebel A, Alene KA, Alijanzadeh M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Aljunid SM, Alkerwi A', Alla F, Allebeck P, Alonso J, Altirkawi K, Alvis-Guzman N, Amare AT, Aminde LN, Amini E, Ammar W, Amoako YA, Anber NH, Andrei CL, Androudi S, Animut MD, Anjomshoa M, Ansari H, Ansha MG, Antonio CAT, Anwari P, Aremu O, Ärnlöv J, Arora A, Arora M, Artaman A, Aryal KK, Asayesh H, Asfaw ET, Ataro Z, Atique S, Atre SR, Ausloos M, Avokpaho EFGA, Awasthi A, Quintanilla BPA, Ayele Y, Ayer R, Azzopardi PS, Babazadeh A, Bacha U, Badali H, Badawi A, Bali AG, Ballesteros KE, Banach M, Banerjee K, Bannick MS, Banoub JAM, Barboza MA, Barker-Collo SL, Bärnighausen TW, Barquera S, Barrero LH, Bassat Q, Basu S, Baune BT, Baynes HW, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bedi N, Beghi E, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, Béjot Y, Bekele BB, Belachew AB, Belay E, Belay YA, Bell ML, Bello AK, Bennett DA, Bensenor IM, Berman AE, Bernabe E, Bernstein RS, Bertolacci GJ, Beuran M, Beyranvand T, Bhalla A, Bhattarai S, Bhaumik S, Bhutta ZA, Biadgo B, Biehl MH, Bijani A, Bikbov B, Bilano V, Bililign N, Bin Sayeed MS, Bisanzio D, Biswas T, Blacker BF, Basara BB, Borschmann R, Bosetti C, Bozorgmehr K, Brady OJ, Brant LC, Brayne C, Brazinova A, Breitborde NJK, Brenner H, Briant PS, Britton G, Brugha T, Busse R, Butt ZA, Callender CSKH, Campos-Nonato IR, Campuzano Rincon JC, Cano J, Car M, Cárdenas R, Carreras G, Carrero JJ, Carter A, Carvalho F, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castillo Rivas J, Castle CD, Castro C, Castro F, Catalá-López F, Cerin E, Chaiah Y, Chang JC, Charlson FJ, Chaturvedi P, Chiang PPC, Chimed-Ochir O, Chisumpa VH, Chitheer A, Chowdhury R, Christensen H, Christopher DJ, Chung SC, Cicuttini FM, Ciobanu LG, Cirillo M, Cohen AJ, Cooper LT, Cortesi PA, Cortinovis M, Cousin E, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cromwell EA, Crowe CS, Crump JA, Cunningham M, Daba AK, Dadi AF, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dang AK, Dargan PI, Daryani A, Das SK, Gupta RD, Neves JD, Dasa TT, Dash AP, Davis AC, Davis Weaver N, Davitoiu DV, Davletov K, de la Hoz FP, de Neve JW, Degefa MG, Degenhardt L, Degfie TT, Deiparine S, Demoz GT, Demtsu BB, Denova-Gutiérrez E, Deribe K, Dervenis N, Des Jarlais DC, Dessie GA, Dey S, Dharmaratne SD, Dicker D, Dinberu MT, Ding EL, Dirac MA, Djalalinia S, Dokova K, Doku DT, Donnelly CA, Dorsey ER, Doshi PP, Douwes-Schultz D, Doyle KE, Driscoll TR, Dubey M, Dubljanin E, Duken EE, Duncan BB, Duraes AR, Ebrahimi H, Ebrahimpour S, Edessa D, Edvardsson D, Eggen AE, el Bcheraoui C, el Sayed Zaki M, el-Khatib Z, Elkout H, Ellingsen CL, Endres M, Endries AY, Er B, Erskine HE, Eshrati B, Eskandarieh S, Esmaeili R, Esteghamati A, Fakhar M, Fakhim H, Faramarzi M, Fareed M, Farhadi F, Farinha CSE, Faro A, Farvid MS, Farzadfar F, Farzaei MH, Feigin VL, Feigl AB, Fentahun N, Fereshtehnejad SM, Fernandes E, Fernandes JC, Ferrari AJ, Feyissa GT, Filip I, Finegold S, Fischer F, Fitzmaurice C, Foigt NA, Foreman KJ, Fornari C, Frank TD, Fukumoto T, Fuller JE, Fullman N, Fürst T, Furtado JM, Futran ND, Gallus S, Garcia-Basteiro AL, Garcia-Gordillo MA, Gardner WM, Gebre AK, Gebrehiwot TT, Gebremedhin AT, Gebremichael B, Gebremichael TG, Gelano TF, Geleijnse JM, Genova-Maleras R, Geramo YCD, Gething PW, Gezae KE, Ghadami MR, Ghadimi R, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Ghasemi-Kasman M, Ghimire M, Gibney KB, Gill PS, Gill TK, Gillum RF, Ginawi IA, Giroud M, Giussani G, Goenka S, Goldberg EM, Goli S, Gómez-Dantés H, Gona PN, Gopalani SV, Gorman TM, Goto A, Goulart AC, Gnedovskaya EV, Grada A, Grosso G, Gugnani HC, Guimaraes ALS, Guo Y, Gupta PC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gupta T, Gutiérrez RA, Gyawali B, Haagsma JA, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hagos TB, Hailegiyorgis TT, Hailu GB, Haj-Mirzaian A, Haj-Mirzaian A, Hamadeh RR, Hamidi S, Handal AJ, Hankey GJ, Harb HL, Harikrishnan S, Haro JM, Hasan M, Hassankhani H, Hassen HY, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hay SI, He Y, Hedayatizadeh-Omran A, Hegazy MI, Heibati B, Heidari M, Hendrie D, Henok A, Henry NJ, Herteliu C, Heydarpour F, Heydarpour P, Heydarpour S, Hibstu DT, Hoek HW, Hole MK, Homaie Rad E, Hoogar P, Hosgood HD, Hosseini SM, Hosseinzadeh M, Hostiuc M, Hostiuc S, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Hsiao T, Hu G, Huang JJ, Husseini A, Hussen MM, Hutfless S, Idrisov B, Ilesanmi OS, Iqbal U, Irvani SSN, Irvine CMS, Islam N, Islam SMS, Islami F, Jacobsen KH, Jahangiry L, Jahanmehr N, Jain SK, Jakovljevic M, Jalu MT, James SL, Javanbakht M, Jayatilleke AU, Jeemon P, Jenkins KJ, Jha RP, Jha V, Johnson CO, Johnson SC, Jonas JB, Joshi A, Jozwiak JJ, Jungari SB, Jürisson M, Kabir Z, Kadel R, Kahsay A, Kalani R, Karami M, Karami Matin B, Karch A, Karema C, Karimi-Sari H, Kasaeian A, Kassa DH, Kassa GM, Kassa TD, Kassebaum NJ, Katikireddi SV, Kaul A, Kazemi Z, Karyani AK, Kazi DS, Kefale AT, Keiyoro PN, Kemp GR, Kengne AP, Keren A, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khafaei B, Khafaie MA, Khajavi A, Khalid N, Khalil IA, Khan EA, Khan MS, Khan MA, Khang YH, Khater MM, Khoja AT, Khosravi A, Khosravi MH, Khubchandani J, Kiadaliri AA, Kibret GD, Kidanemariam ZT, Kiirithio DN, Kim D, Kim YE, Kim YJ, Kimokoti RW, Kinfu Y, Kisa A, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Kivimäki M, Knudsen AKS, Kocarnik JM, Kochhar S, Kokubo Y, Kolola T, Kopec JA, Koul PA, Koyanagi A, Kravchenko MA, Krishan K, Kuate Defo B, Kucuk Bicer B, Kumar GA, Kumar M, Kumar P, Kutz MJ, Kuzin I, Kyu HH, Lad DP, Lad SD, Lafranconi A, Lal DK, Lalloo R, Lallukka T, Lam JO, Lami FH, Lansingh VC, Lansky S, Larson HJ, Latifi A, Lau KMM, Lazarus JV, Lebedev G, Lee PH, Leigh J, Leili M, Leshargie CT, Li S, Li Y, Liang J, Lim LL, Lim SS, Limenih MA, Linn S, Liu S, Liu Y, Lodha R, Lonsdale C, Lopez AD, Lorkowski S, Lotufo PA, Lozano R, Lunevicius R, Ma S, Macarayan ERK, Mackay MT, MacLachlan JH, Maddison ER, Madotto F, Magdy Abd el Razek H, Magdy Abd el Razek M, Maghavani DP, Majdan M, Majdzadeh R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Manda AL, Mandarano-Filho LG, Manguerra H, Mansournia MA, Mapoma CC, Marami D, Maravilla JC, Marcenes W, Marczak L, Marks A, Marks GB, Martinez G, Martins-Melo FR, Martopullo I, März W, Marzan MB, Masci JR, Massenburg BB, Mathur MR, Mathur P, Matzopoulos R, Maulik PK, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGrath JJ, McKee M, McMahon BJ, Mehata S, Mehndiratta MM, Mehrotra R, Mehta KM, Mehta V, Mekonnen TC, Melese A, Melku M, Memiah PTN, Memish ZA, Mendoza W, Mengistu DT, Mengistu G, Mensah GA, Mereta ST, Meretoja A, Meretoja TJ, Mestrovic T, Mezgebe HB, Miazgowski B, Miazgowski T, Millear AI, Miller TR, Miller-Petrie MK, Mini GK, Mirabi P, Mirarefin M, Mirica A, Mirrakhimov EM, Misganaw AT, Mitiku H, Moazen B, Mohammad KA, Mohammadi M, Mohammadifard N, Mohammed MA, Mohammed S, Mohan V, Mokdad AH, Molokhia M, Monasta L, Moradi G, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moradinazar M, Moraga P, Morawska L, Moreno Velásquez I, Morgado-da-Costa J, Morrison SD, Moschos MM, Mouodi S, Mousavi SM, Muchie KF, Mueller UO, Mukhopadhyay S, Muller K, Mumford JE, Musa J, Musa KI, Mustafa G, Muthupandian S, Nachega JB, Nagel G, Naheed A, Nahvijou A, Naik G, Nair S, Najafi F, Naldi L, Nam HS, Nangia V, Nansseu JR, Nascimento BR, Natarajan G, Neamati N, Negoi I, Negoi RI, Neupane S, Newton CRJ, Ngalesoni FN, Ngunjiri JW, Nguyen AQ, Nguyen G, Nguyen HT, Nguyen HT, Nguyen LH, Nguyen M, Nguyen TH, Nichols E, Ningrum DNA, Nirayo YL, Nixon MR, Nolutshungu N, Nomura S, Norheim OF, Noroozi M, Norrving B, Noubiap JJ, Nouri HR, Nourollahpour Shiadeh M, Nowroozi MR, Nyasulu PS, Odell CM, Ofori-Asenso R, Ogbo FA, Oh IH, Oladimeji O, Olagunju AT, Olivares PR, Olsen HE, Olusanya BO, Olusanya JO, Ong KL, Ong SKS, Oren E, Orpana HM, Ortiz A, Ortiz JR, Otstavnov SS, Øverland S, Owolabi MO, Özdemir R, P A M, Pacella R, Pakhale S, Pakhare AP, Pakpour AH, Pana A, Panda-Jonas S, Pandian JD, Parisi A, Park EK, Parry CDH, Parsian H, Patel S, Pati S, Patton GC, Paturi VR, Paulson KR, Pereira A, Pereira DM, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Piel FB, Pigott DM, Pillay JD, Pirsaheb M, Pishgar F, Polinder S, Postma MJ, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Pujar A, Prakash S, Prasad N, Purcell CA, Qorbani M, Quintana H, Quistberg DA, Rade KW, Radfar A, Rafay A, Rafiei A, Rahim F, Rahimi K, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Rahman M, Rahman MHU, Rahman MA, Rai RK, Rajsic S, Ram U, Ranabhat CL, Ranjan P, Rao PC, Rawaf DL, Rawaf S, Razo-García C, Reddy KS, Reiner RC, Reitsma MB, Remuzzi G, Renzaho AMN, Resnikoff S, Rezaei S, Rezaeian S, Rezai MS, Riahi SM, Ribeiro ALP, Rios-Blancas MJ, Roba KT, Roberts NLS, Robinson SR, Roever L, Ronfani L, Roshandel G, Rostami A, Rothenbacher D, Roy A, Rubagotti E, Sachdev PS, Saddik B, Sadeghi E, Safari H, Safdarian M, Safi S, Safiri S, Sagar R, Sahebkar A, Sahraian MA, Salam N, Salama JS, Salamati P, Saldanha RDF, Saleem Z, Salimi Y, Salvi SS, Salz I, Sambala EZ, Samy AM, Sanabria J, Sanchez-Niño MD, Santomauro DF, Santos IS, Santos JV, Milicevic MMS, Sao Jose BP, Sarker AR, Sarmiento-Suárez R, Sarrafzadegan N, Sartorius B, Sarvi S, Sathian B, Satpathy M, Sawant AR, Sawhney M, Saxena S, Sayyah M, Schaeffner E, Schmidt MI, Schneider IJC, Schöttker B, Schutte AE, Schwebel DC, Schwendicke F, Scott JG, Sekerija M, Sepanlou SG, Serván-Mori E, Seyedmousavi S, Shabaninejad H, Shackelford KA, Shafieesabet A, Shahbazi M, Shaheen AA, Shaikh MA, Shams-Beyranvand M, Shamsi M, Shamsizadeh M, Sharafi K, Sharif M, Sharif-Alhoseini M, Sharma R, She J, Sheikh A, Shi P, Shiferaw MS, Shigematsu M, Shiri R, Shirkoohi R, Shiue I, Shokraneh F, Shrime MG, Si S, Siabani S, Siddiqi TJ, Sigfusdottir ID, Sigurvinsdottir R, Silberberg DH, Silva DAS, Silva JP, Silva NTD, Silveira DGA, Singh JA, Singh NP, Singh PK, Singh V, Sinha DN, Sliwa K, Smith M, Sobaih BH, Sobhani S, Sobngwi E, Soneji SS, Soofi M, Sorensen RJD, Soriano JB, Soyiri IN, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Srinivasan V, Stanaway JD, Starodubov VI, Stathopoulou V, Stein DJ, Steiner C, Stewart LG, Stokes MA, Subart ML, Sudaryanto A, Sufiyan M'B, Sur PJ, Sutradhar I, Sykes BL, Sylaja PN, Sylte DO, Szoeke CEI, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tabuchi T, Tadakamadla SK, Takahashi K, Tandon N, Tassew SG, Taveira N, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Tekalign TG, Tekle MG, Temsah MH, Temsah O, Terkawi AS, Teshale MY, Tessema B, Tessema GA, Thankappan KR, Thirunavukkarasu S, Thomas N, Thrift AG, Thurston GD, Tilahun B, To QG, Tobe-Gai R, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Torre AE, Tortajada-Girbés M, Touvier M, Tovani-Palone MR, Tran BX, Tran KB, Tripathi S, Troeger CE, Truelsen TC, Truong NT, Tsadik AG, Tsoi D, Tudor Car L, Tuzcu EM, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Ullah I, Undurraga EA, Updike RL, Usman MS, Uthman OA, Uzun SB, Vaduganathan M, Vaezi A, Vaidya G, Valdez PR, Varavikova E, Vasankari TJ, Venketasubramanian N, Villafaina S, Violante FS, Vladimirov SK, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wagner GR, Wagnew FS, Waheed Y, Wallin MT, Walson JL, Wang Y, Wang YP, Wassie MM, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Weldegebreal F, Weldegwergs KG, Werdecker A, Werkneh AA, West TE, Westerman R, Whiteford HA, Widecka J, Wilner LB, Wilson S, Winkler AS, Wiysonge CS, Wolfe CDA, Wu S, Wu YC, Wyper GMA, Xavier D, Xu G, Yadgir S, Yadollahpour A, Yahyazadeh Jabbari SH, Yakob B, Yan LL, Yano Y, Yaseri M, Yasin YJ, Yentür GK, Yeshaneh A, Yimer EM, Yip P, Yirsaw BD, Yisma E, Yonemoto N, Yonga G, Yoon SJ, Yotebieng M, Younis MZ, Yousefifard M, Yu C, Zadnik V, Zaidi Z, Zaman SB, Zamani M, Zare Z, Zeleke AJ, Zenebe ZM, Zhang AL, Zhang K, Zhou M, Zodpey S, Zuhlke LJ, Naghavi M, Murray CJL. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis DL. Short-term improvements in public health from global-climate policies on fossil-fuel combustion: an interim report. Lancet. 1997;350(9088):1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United Nations. Big data for sustainable development. United Nations. Global Issues Web site. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/big-data-for-sustainable-development. Published 2021. Accessed 4/5/2021, 2021.

- 44.Snyder N. UN global working group on big data. Washington DC: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeSalvo K, Lurie N, Finne K, Worrall C, Bogdanov A, Dinkler A, Babcock S, Kelman J. Using Medicare data to identify individuals who are electricity dependent to improve disaster preparedness and response. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1160–1164. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdolhosseini Qomi MJ, Noshadravan A, Sobstyl JM, et al. Data analytics for simplifying thermal efficiency planning in cities. J R Soc Interface. 2016;13(117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Partridge I, Gamkhar S. A methodology for estimating health benefits of electricity generation using renewable technologies. Environ Int. 2012;39(1):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Penn SL, Arunachalam S, Woody M, Heiger-Bernays W, Tripodis Y, Levy JI. Estimating state-specific contributions to PM2.5- and O3-related health burden from residential combustion and electricity generating unit emissions in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(3):324–332. doi: 10.1289/EHP550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xing X, Wang J, Liu T, Liu H, Zhu Y. How energy consumption and pollutant emissions affect the disparity of public health in countries with high fossil energy consumption. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4678. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dockery DW, Rich DQ, Goodman PG, et al. Effect of air pollution control on mortality and hospital admissions in Ireland. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2013;176:3–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen C, Chen B, Wang B, Huang C, Zhao J, Dai Y, Kan H. Low-carbon energy policy and ambient air pollution in Shanghai, China: a health-based economic assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2007;373(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mestl HE, Aunan K, Seip HM. Health benefits from reducing indoor air pollution from household solid fuel use in China--three abatement scenarios. Environ Int. 2007;33(6):831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S-I, Lee L-T, Zou M-L, Fan C-W, Yaung C-L. Pregnancy outcome of women in the vicinity of nuclear power plants in Taiwan. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2010;49(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00411-009-0246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 42 kb)