Abstract

Objectives

The Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has imposed restrictions on people’s social behavior. However, there is limited evidence regarding the relationship between changes in social participation and depressive symptom onset among older adults during the pandemic. We examined the association between changes in social participation and the onset of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

This was a longitudinal study.

Setting

Communities in Minokamo City, a semi-urban area in Japan.

Participants

We recruited community-dwelling older adults aged ≥ 65 years using random sampling. Participants completed a questionnaire survey at baseline (March 2020) and follow-up (October 2020).

Measurements

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Two-Question Screen. Based on their social participation status in March and October 2020, participants were classified into four groups: “continued participation,” “decreased participation,” “increased participation,” and “consistent non-participation.”

Results

A total of 597 older adults without depressive symptoms at baseline were analyzed (mean age = 79.8 years; 50.4% females). Depressive symptoms occurred in 20.1% of the participants during the observation period. Multivariable Poisson regression analysis showed that decreased social participation was significantly associated with the onset of the depressive symptoms, compared to continued participation, after adjusting for all covariates (incidence rate ratio = 1.59, 95% confidence interval = 1.01–2.50, p = 0.045).

Conclusion

Older adults with decreased social participation during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated a high risk of developing depressive symptoms. We recommend that resuming community activities and promoting the participation of older adults, with sufficient consideration for infection prevention, are needed to maintain mental health among older adults.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available for this article at 10.1007/s12603-021-1674-7 and is accessible for authorized users.

Key words: COVID-19, depressive symptoms, longitudinal study, novel coronavirus disease infection, social participation

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has caused an adverse global impact, with a high morbidity and mortality rate; moreover, it is significant in older adults (1, 2). In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic (3). While effective pharmacological interventions have not been fully established, COVID-19 management largely depends on public health measures to mitigate infection spread and flatten the pandemic curve; these measures include bans on public gatherings, stay-at-home policies, and physical distancing strategies (4).

Although these measures have helped to stop the spread of the infectious disease (5), COVID-19 management policies have led to severe restrictions on people’s social behaviors. For instance, a significant decline in social interactions with friends has been observed (6, 7). These social and behavioral restrictions could have unintended secondary effects. Several previous studies have revealed the adverse mental health effects of the pandemic due to social disconnectedness (8–10). Therefore, it is necessary to understand the factors influencing people’s mental health deterioration.

In Japan, during the first wave of COVID-19, the government declared a nationwide state of emergency on April 16, 2020, and individuals were required to maintain social distancing, while refraining from non-essential activities (lifted on May 31, 2020). These measures have actually limited people’s social interaction and social activity (11). As a response to the second wave, a local-prefectural-level emergency declaration was established to declare self-restraint at restaurants at night (lifted in early September 2020) (12, 13). Furthermore, the state of emergency was repeatedly declared from January–February and from April–June 2021, along with restrictions on people’s social activities (14). Japan has not implemented a “lockdown” as introduced by other countries; however, people’s social behaviors continue to be restricted (15).

In response to the rapidly increasing rate of aging, the Japanese government has been implementing policies with community-based population strategies since 2015 to extend healthy life expectancy and prevent long-term care (LTC) for older adults (16). This strategy has begun to promote community activities, such as senior salons, initiated by central and local governments, to facilitate older adults’ social participation (16). Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has radically restricted the social activities of community-dwelling older adults, and decreased their opportunities for social participation, leading to a loss of social connections. These circumstances may result in depressive symptoms among older adults. However, there is insufficient empirical evidence regarding the association between reduced social participation and depressive symptom onset among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the changes in social participation among older adults in the first and second waves of COVID-19 in Japan; moreover, we aimed to clarify the association between social participation changes and depressive symptom onset during the pandemic. Specifically, we used seven-month longitudinal data, with the baseline data collected just before Japan declared a state of emergency (March 2020) that severely restricted people’s social behaviors.

Methods

Study population

In this longitudinal study, mailed questionnaire surveys were conducted before and after the two emergency declarations in response to the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in the target municipality. The baseline survey was conducted from March 3–16, 2020, just before the nationwide state of emergency declaration in response to the pandemic’s first wave (11). The follow-up survey was conducted from October 16–30, 2020, after the emergency declaration at the local prefecture level in the target survey area, in response to the pandemic’s second wave (from July 31–August 31, 2020) (12). At baseline, non-institutionalized older adults aged ≥ 65 years who lived in Minokamo City, Gifu, a semi-urban area in Japan, were recruited using random sampling. The inclusion criteria were: participants not eligible for public LTC insurance benefits or those with “support need levels” one or two in the public LTC insurance system (the Japanese public LTC insurance system classifies frail older adults into seven levels: “support need levels” one and two and “care need levels” one to five; higher numbers indicate increased need) (17).

Then, 2,000 older adults were surveyed using a mailed questionnaire, of which 1,350 individuals responded to the baseline survey (response rate: 67.5%). Of these, 1,106 individuals completed the follow-up survey and were included in this study (follow-up rate: 81.9%). The following individuals were eliminated from the analysis at baseline: those with an invalid age and/or sex (n = 3), those with self-reported dementia or depression (n = 17), those with missing data for the items on present illness (n = 3), those with depressive symptoms at baseline (n = 435), as assessed by the Two-Question Screen (18, 19), and those with missing data for the items on depressive symptoms (n = 68). Subsequently, 597 participants were included in the final analysis.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed in the baseline and follow-up, using the Two-Question Screen, consisting of the following questions: (1) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and (2) “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” Each of these questions had possible responses of “Yes” or “No” (18, 19). We identified those who answered “Yes” to either or both questions as showing depressive symptoms. The Two-Question Screen has been previously validated and shows comparable performance with other measurements: for major depression, 96% and 57% sensitivity and specificity, respectively; for depression, 91.8% and 67.7% sensitivity and specificity, respectively (18, 19). We excluded participants with depressive symptoms at baseline from the analysis and followed up for the onset of new depressive symptoms during the observation period.

Changes in social participation status

At the baseline and follow-up, participants were assessed for participation in six community-based activities: volunteer groups, sports groups or clubs, hobby activity groups, senior citizen clubs, study or cultural groups, and LTC prevention activities. For each group, the frequency of participation was assessed. Those who had participated in any group less than once a month were defined as “non-participation,” whereas others were defined as “participation” (20). Based on the social participation status at baseline and follow-up, we divided participants into four groups: “continued participation” (“participation” at both times), “decreased participation” (“participation” in the baseline, and “non-participation” in the follow-up), “increased participation” (“non-participation” in the baseline and “participation” in the follow-up), and “consistent non-participation” (“non-participation” at both times).

Covariates

The covariates included age, sex, living arrangement, educational attainment, subjective economic status, basic activities of daily living (BADL), present illness, motor function, subjective cognitive function, frequency of going out, and frequency of meeting with friends. Living arrangement was dichotomized as “living with others” or “living alone.” Educational attainment was dichotomized as “low” (< 10 years) or “high” (≥ 10). Subjective economic status was dichotomized from five responses as “severe” (“very severe” or “slightly severe”) or “rich” (“normal,” “slightly rich,” or “very rich”). BADL was assessed using the question, “Do you need someone’s care or assistance in your daily life?” This variable was dichotomized into “no difficulty” (answer: “no need for care or assistance”) or “difficulty” (answer: “need some care or assistance but do not currently receive any” or “currently receive some care”). Regarding present illness, participants selected those illnesses that they received treatment for, from a list of 16, the number of selected illnesses was then added. Motor function was assessed using a 5-point subitem of the Kihon Check List (KCL), widely used for frailty screening in Japan (21). These responses were classified as “not impaired” (< three points) or “impaired” (≥ three points). Subjective cognitive function was assessed by a 3-point subitem of the KCL, and dichotomized as “not impaired” (zero points) or “impaired” (≥ one point) (22). The frequency of going out (days/week) was categorized as “≥ five/week,” “two to four/week,” or “≤ one/week”. The frequency of meeting with friends was categorized as “≥ once/week,” “once/month to once/week,” or “< once/month.”

Statistical analysis

First, descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the participants’ characteristics according to depressive symptom onset. Second, the prevalence of those with no social participation at baseline and follow-up was described. Third, to examine the association between the changes in social participation and depressive symptom onset, we conducted multivariable Poisson regression analysis with robust standard errors and obtained incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for depressive symptom onset. Because the percentage of individuals who experienced depressive symptoms was more than 10%, the adjusted odds ratios derived from logistic regression analysis could no longer approximate the IRR (23). As an explanatory variable, changes in social participation status were included in the analytical model. Two analytical models were created using crude and all-covariate-adjusted models.

For the sensitivity analysis, we conducted a similar analysis by changing the cut-off point of frequency of participation; we redefined “participation” as participation more than a few times a year, while “non-participation” as no participation at all in a year.

To mitigate the potential bias caused by missing information, we applied the multiple imputation approach under the missing at random (MAR) assumption (i.e., the missing data mechanism depended only on observed variables). We generated 10 imputed datasets using the multiple imputations by chained equations (MICE) procedure and pooled the results using the standard Rubin’s rule (24).

The significance level was set at p < 0.05. We used R software Version 3.6.3. for Windows (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) for all statistical analyses. For the multiple imputation approach, we used the MICE function (MICE package).

Results

Overall, 597 participants were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows participant characteristics according to depressive symptom onset. The participants’ mean age was 79.8 years (standard deviation = 4.7), and 301 participants (50.4%) were female. Those who developed depressive symptoms at follow-up were more likely to be living alone, have low education, severe economic status, impaired BADL, subjective cognitive impairment, and a lower frequency of going out.

Table 1.

Participants’ baseline characteristics according to depressive symptom onset

| Overall | Depressive symptoms at follow-up† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No onset | Onset | ||||

| n = 597 | n = 434 | n = 130 | p-value‡ | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 79.8 (4.7) | 79.7 (4.6) | 80.1 (5.1) | 0.471 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Men | 296 (49.6) | 221 (50.9) | 61 (46.9) | 0.484 |

| Women | 301 (50.4) | 213 (49.1) | 69 (53.1) | ||

| Living arrangement, n (%) | Living with others | 490 (82.1) | 370 (85.3) | 97 (74.6) | 0.021 |

| Living alone | 77 (12.9) | 47 (10.8) | 24 (18.5) | ||

| Missing | 30 (5.0) | 17 (3.9) | 9 (6.9) | ||

| Educational attainment, n (%) | High | 389 (65.2) | 294 (67.7) | 76 (58.5) | 0.107 |

| Low | 199 (33.3) | 136 (31.3) | 50 (38.5) | ||

| Missing | 9 (1.5) | 4 (0.9) | 4 (3.1) | ||

| Subjective economic status, n (%) | Severe | 105 (17.6) | 67 (15.4) | 32 (24.6) | |

| Rich | 472 (79.1) | 353 (81.3) | 94 (72.3) | 0.018 | |

| Missing | 20 (3.4) | 14 (3.2) | 4 (3.1) | ||

| BADL performance, n (%) | Not difficulty | 539 (90.3) | 399 (91.9) | 111 (85.4) | 0.041 |

| Difficulty | 31 (5.2) | 18 (4.1) | 12 (9.2) | ||

| Missing | 27 (4.5) | 17 (3.9) | 7 (5.4) | ||

| Number of present illnesses, mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.2) | 0.178 | |

| Motor function, n (%) | Not impaired | 536 (89.8) | 390 (89.9) | 117 (90.0) | 0.708 |

| Impaired | 44 (7.4) | 32 (7.4) | 11 (8.5) | ||

| Missing | 17 (2.8) | 12 (2.8) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Subjective cognitive function, n (%) | Not impaired | 327 (54.8) | 253 (58.3) | 58 (44.6) | 0.024 |

| Impaired | 261 (43.7) | 178 (41.0) | 66 (50.8) | ||

| Missing | 9 (1.5) | 3 (0.7) | 6 (4.6) | ||

| Frequency of going out, n (%) | ≥ 5 days/week | 242 (40.5) | 177 (40.8) | 48 (36.9) | 0.099 |

| 2 to 4 days/week | 252 (42.2) | 190 (43.8) | 51 (39.2) | ||

| ≤ 1 days/week | 87 (14.6) | 57 (13.1) | 27 (20.8) | ||

| Missing | 16 (2.7) | 10 (2.3) | 4 (3.1) | ||

| Frequent of meeting with friends, n (%) | ≥ once/week | 248 (41.5) | 182 (41.9) | 51 (39.2) | 0.825 |

| Once/month to once /week | 195 (32.7) | 141 (32.5) | 44 (33.8) | ||

| < once/month | 139 (23.3) | 99 (22.8) | 32 (24.6) | ||

| Missing | 15 (2.5) | 12 (2.8) | 3 (2.3) | ||

| Social participation, n (%) | ≥ once/month | 320 (53.6) | 240 (55.3) | 64 (49.2) | 0.384 |

| < once/month | 139 (23.3) | 100 (23.0) | 33 (25.4) | ||

| Missing | 138 (23.1) | 94 (21.7) | 33 (25.4) | ||

BADL, basic activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation; †Missing data: n = 33; ‡Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests (p-value when the missing data were excluded).

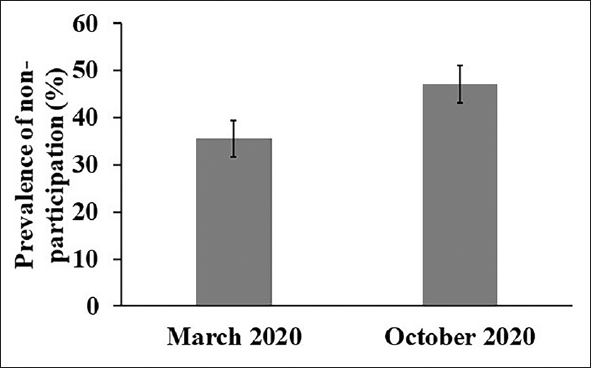

Figure 1 shows the changes in the prevalence of non-participation from March–October 2020. Overall, 35.5% (95%CI = 32.7–39.4) and 47.1% (95%CI = 43.1–51.1) older adults did not participate in community groups more than once a month in March and October, respectively.

Figure 1.

Changes in prevalence of non-social participation in March and October 2020

The error bar indicates 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The values were imputed by the multiple imputation approach. The prevalence of non-participation was 35.5% (95% CI = 32.7–39.4) in March and 47.1% (95%CI = 43.1–51.1) in October 2020.

Table 2 shows the association between the changes in social participation status and depressive symptom onset. The number of depressive symptom onset in each group was 58 (20.1%) for those with continued participation, 32 (31.7%) for those with decreased participation, 5 (17.9%) for those with increased participation, and 50 (27.8%) for those with consistent non-participation. The multivariable Poisson regression analysis revealed that, compared to the continued participation group, decreased participation group was significantly associated with the onset of depressive symptoms, after adjusting for all covariates in this study (all information about the results is presented in Supplementary Table 1); IRRs (95% CIs) on depressive symptom onset were 1.59 (1.01–2.50) for decreased participation (p = 0.045), 0.84 (0.28–2.55) for increased participation (p = 0.757), and 1.29 (0.86–1.95) for consistent non-participation (p = 0.244). Similar trends were confirmed in the sensitivity analysis in which the definition of social participation was changed to participation more than a few times a year (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between changes in social participation status and depressive symptom onset, multivariable Poisson regression analysis with multiple imputation approach

| Changes in social participation status† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continued participation | Decreased participation | Increased participation | Consistent non-participation | |

| n = 288 | n = 101 | n = 28 | n = 180 | |

| Depressive symptom onset, n (%) | 58 (20.1) | 32 (31.7) | 5 (17.9) | 50 (27.8) |

| Crude IRR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.57 (1.02–2.41), p = 0.041* | 0.88 (0.28–2.71), p = 0.822 | 1.37 (0.95–1.97), p = 0.095 |

| Adjusted IRR (95% CI‡ | Reference | 1.59 (1.01–2.50), p = 0.045* | 0.84 (0.28–2.55). p = 0.757 | 1.29 (0.86–1.95), p = 0.244 |

CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio; *, p < 0.05; †Missing data were imputed by the multiple imputation approach; ‡Adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment, subjective economic status, basic activities of daily living (BADL) performance, present illness, motor function, subjective cognitive function, frequency of going out, and frequency of meeting with friends at baseline; The full results are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

This longitudinal study demonstrated that decreased participation in community activities was associated with depressive symptom onset among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings suggest that pandemic-related restrictions on community activities and reduced social participation opportunities may result in the development of depressive symptoms among older adults.

Our results revealed that the number of older adults who did not participate in community activities increased approximately 1.3-fold from March–October 2020, in response to the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has severely restricted people’s social activities, including outdoor events and face-to-face interactions to mitigate infection risk (6, 7). Particularly, the risk of infection and its fatality is more noticeable among older adults, resulting in increased anxiety and reduced participation in community social activities (2). Recently in Japan, population strategies based on the development of community activities for older adults have been positioned as an essential policy to prevent LTC (16). However, external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can cause a sudden interruption of participation in community activities that were being fostered, and thus strategies for the prevention of LTC among older adults might face challenges.

The present study indicated a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms among older adults with reduced social participation during the pandemic. While there were no comparisons drawn with a non-pandemic period, sudden restrictions on social activities due to the pandemic may result in depressive symptom onset in older adults. Prior studies have shown that engaging in community social activities can lead to improved mental health for older adults by enhancing social support and self-esteem, providing social roles, and promoting physical activities through group exercise (25–27). However, a sudden decrease in opportunities for social participation due to the external shock of the pandemic may deprive them of these functions, thus increasing the risk of depressive symptoms. Meanwhile, our results showed that those with consistent non-participation did not have a significant risk of depressive symptom onset. While the possibility of long-term negative impact on mental health due to a lack of social participation cannot be disregarded, our short observation period of seven months may not have detected a strong negative impact. Therefore, although consideration for those who continue to lack social participation may be necessary depending on the duration of the pandemic, we believe that addressing mental health issues for those who have suddenly lost opportunities for social participation is urgently needed.

Although there are country-wise differences in infection rates, in the prevalence of vaccinated persons, and infection control measures, maintaining social connections and participating in community activities are crucial to prevent depressive symptoms among older adults. Particularly, Japan has not introduced lockdown measures, unlike other countries; thus, it is recommended that resuming community activities of older adults with due consideration for infection control is warranted to minimize secondary health damage. Additionally, social connections can be maintained in various ways. For instance, online communication and remote social interactions through telephone and video chatting could be helpful (28, 29).

Although this study provided important insights into the effects of restricted social behavior in older adults using longitudinal data from the COVID-19 pandemic, there are several limitations. First, our baseline survey (March 2020) was conducted when the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning in Japan (13). Thus, changes in an individual’s psychological and social behavior status may have already begun to occur. However, our baseline survey was conducted just before the declaration of the state of emergency, which imposed strong behavioral restrictions (30). Therefore, the baseline was relatively close to normal times, and the effects may not be immense. Second, the variables used in this study were assessed using a self-reported questionnaire, which can lead to information bias. Particularly, the assessment of depressive symptoms using two simple items may have resulted in misclassifications. However, the depressive symptom indicator used in this study was validated (18, 19). Moreover, we believe that our longitudinal investigation of depressive symptoms during the pandemic has some meaning. Third, in this study, some participants dropped out from the follow-up survey, which might have led to an underestimation of the prevalence of consistent non-participation in community activities. Additionally, selection bias due to dropouts in the follow-up may have reduced the internal validity of the results. However, the effect could not be substantial because the follow-up rate was relatively high at 81.9%. Finally, although our survey had area-level representation based on random sampling, it only involved a single municipality in a semi-urban area in Japan. That may reduce the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

The present study indicated that decreased social participation during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a risk of new depressive symptom onset. Restrictions on community activities due to the pandemic may reduce older adults’ social participation opportunities, thus resulting in a mental health crisis. Resumption of community activities and promotion of participation, with due consideration for infection control, is required to maintain mental health among older adults.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material, approximately 28 KB.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the staff of the Minokamo City office and all the participants of this study.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, grant numbers 21K17322 and 19K02200. This study was also supported by a research grant from the Health Science Center Foundation (2019–2020), the Japan Full-Hap Survey Research Grant from the Japan Small Business Welfare Foundation (2020), the Lotte Research Promotion Grant (2021), a grant from the Tanuma Green House Foundation (2021), the Yuumi Memorial Foundation for Home Health Care, and the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (21–17).

Ethical standards

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (No. 20TB4) and Seijoh University (No. 2020C0013). The mailed questionnaire was accompanied by an explanation of the study purpose; participants were informed that they were no consequences to withdrawing from the study at any point. Informed consent was obtained when participants agreed to complete the questionnaire and returned the completed survey. All procedures conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 2.World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western: Pacific. Guidance on COVID-19 for the care of older people and people living in long-term care facilities, other nonacute care facilities and home care Manila; 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization: Archived: WHO timeline — COVID-19; 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19 (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 4.Hartley DM, Perencevich EN. Public health interventions for COVID-19: Emerging evidence and implications for an evolving public health crisis. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1908–1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islam N, Sharp SJ, Chowell G, Shabnam S, Kawachi I, Lacey B, et al. Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus disease 2019: Natural experiment in 149 countries. BMJ. 2020;370:m2743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabinet Secretariat: Basic data on new social security issues in view of the spread of the novel coronavirus infection. Cabinet Secretariat; 2020. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/zensedaigata_shakaihoshou/dai7/siryou2.pdf (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 7.Philpot LM, Ramar P, Roellinger DL, Barry BA, Sharma P, Ebbert JO. Changes in social relationships during an initial “stay-at-home” phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal survey study in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2021;274:113779. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stickley A, Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. Loneliness and COVID-19 preventive behaviours among Japanese adults. J Public Health (Oxf) 2021;43(1):53–60. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Violant-Holz V, Gallego-Jiménez MG, González-González CS, Muñoz-Violant S, Rodríguez MJ, Sansano-Nadal O, et al. Psychological health and physical activity levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(24). doi:10.3390/ijerph17249419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Sommerlad A, Marston L, Huntley J, Livingston G, Lewis G, Steptoe A, et al. Social relationships and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal analysis of the COVID-19 Social Study. Psychol Med. 2021;13:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prime minister of Japan and His cabinet. [COVID-19] Press Conference by the Prime Minister Regarding the Declaration of a State of Emergency. 2020. https://japan.kantei.go.jp/98_abe/statement/202004/_00001.html (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 12.Gifu Prefectural Office: Information on a new type of coronavirus infection in Gifu Prefecture. Emergency Measures for “second wave emergency” (Governor’s Message); 2020. https://www.pref.gifu.lg.jp/site/covid19/62123.html (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 13.Karako K, Song P, Chen Y, Tang W, Kokudo N. Overview of the characteristics of and responses to the three waves of COVID-19 in Japan during 2020–2021. BioSci Trends. 2021;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.5582/bst.2021.01019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabinet Secretariat, Government of Japan. Measures against novel coronavirus infections; 2021. https://corona.go.jp/emergency/ (Accessed July 10, 2021)

- 15.Inoue H. Japanese strategy to COVID-19: How does it work? Glob Health Med. 2020;2(2):131–132. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito J, Haseda M, Amemiya A, Takagi D, Kondo K, Kondo N. Community-based care for healthy ageing: Lessons from Japan. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(8):570–574. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.223057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):522–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY. Comparison of diagnostic performance of two-Question Screen and 15 depression screening instruments for older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):255–260. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.186932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito M, Kondo N, Aida J, Kawachi I, Koyama S, Ojima T, et al. Development of an instrument for community-level health related social capital among Japanese older people: The JAGES Project. J Epidemiol. 2017;27(5):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satake S, Kinoshita K, Matsui Y, Arai H. Physical domain of the Kihon Checklist: A possible surrogate for physical function tests. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(6):644–646. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomata Y, Sugiyama K, Kaiho Y, Sugawara Y, Hozawa A, Tsuji I. Predictive ability of a simple subjective memory complaints scale for incident dementia: Evaluation of Japan’s national checklist, the “Kihon Checklist”. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(9):1300–1305. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thoits PA. Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Soc Psychol Q. 2012;75(4):360–384. doi: 10.1177/0190272512459662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanamori S, Takamiya T, Inoue S. Group exercise for adults and elderly: Determinants of participation in group exercise and its associations with health outcome. J Phys Fit Sports Med. 2015;4(4):315–320. doi: 10.7600/jpfsm.4.315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arpino B, Pasqualini M, Bordone V, Solé-Auró A. Older people’s non-physical contacts and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown. Gerontologist. 2020;61(2):176–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakagomi A, Shiba K, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Can online communication prevent depression among older people? A longitudinal analysis. J Appl Gerontol 2020:733464820982147. doi:10.1177/0733464820982147 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Kuniya T. Evaluation of the effect of the state of emergency for the first wave of COVID-19 in Japan. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material, approximately 28 KB.