Abstract

Progress in life-supporting kidney transplantation in the genetically-engineered pig-to-nonhuman primate model has been encouraging, with pig kidneys sometimes supporting life for > 1 year. What steps need to be taken by (i) the laboratory team, and (ii) the clinical team to prepare for the first clinical trial? The major topics include (i) what currently-available genetic modifications are optimal to reduce the possibility of graft rejection, (ii) what immunosuppressive therapeutic regimen is optimal, and (iii) what steps need to be taken to minimize the risk of transfer of an infectious microorganism with the graft. We suggest that patients who are unlikely to live long enough to receive a kidney from a deceased human donor would benefit from the opportunity of a period of dialysis-free support by a pig kidney, and the experience gained would enable xenotransplantation to progress much more rapidly than if we remain in the laboratory.

Keywords: Kidney; Nonhuman primate; Patient selection; Pig, genetically-engineered; Xenotransplantation; Clinical; Preclinical

Abbreviations: CMV, Cytomegalovirus; NHP, Nonhuman primate; TKO, Triple-knockout (i.e., in a pig in which the three known carbohydrate xenoantigens have been deleted)

1. Introduction

Progress in life-supporting kidney and heart transplantation in genetically-engineered pig-to-nonhuman primate (NHP) models has been encouraging, with pig kidneys supporting life for > 1 year [1,2], and pig hearts for > 6 months [3,4]. (Much less progress has been achieved with pig liver and lung xenotransplantation.) As a result, attention is now being directed to planning the initial clinical trials [5].

It is therefore important to consider what steps need to be taken (i) by the laboratory team in preparation for the first clinical trials, and (ii) by the clinical team to prepare for the first trial, e.g., the selection of the first patients who ethically might be offered a pig organ. We suggest that it is unrealistic to anticipate uniformly great prolongation (i.e., several years) of graft and recipient survival after clinical pig kidney or heart transplantation (although this may occur in some patients, as it did after the early kidney and heart allotransplants [6], [7], [8]), but there is every reason to believe that a pig organ could act as an effective relatively long-term bridge to allotransplantation.

Although this approach would not immediately increase the number of ‘donor’ organs available, it would at least maintain life while the patient awaited a suitable allograft (just as dialysis and ventricular assist devices do today). Even if not every patient can be maintained until a suitable allograft becomes available, the experience gained would be valuable in determining the problems that need to be overcome if xenotransplantation is to progress to destination therapy.

For a number of reasons, we suggest that the first clinical trial should be of pig kidney, rather than heart, transplantation [9]. Important considerations include the fact that, if the pig graft fails from rejection, or if the patient develops a life-threatening systemic infection that is resistant to the available therapy, the kidney can be excised, all immunosuppressive therapy discontinued, and dialysis recommenced. Comparable rescue therapy is less easily available to a patient whose pig heart has failed completely. Hereafter, therefore, we shall direct our comments to a first clinical trial of pig kidney transplantation.

The national regulatory authorities are likely to require the demonstration of ‘complication-free’ survival of a life-supporting pig kidney in a NHP for 6 months or longer in a series of at least 6 consecutive experiments before a clinical trial would be considered appropriate. ‘Complication-free’ implies absence of irreversible rejection or life-threatening infection, and without features of severe rejection on graft biopsies or of chronic infection or de novo neoplasia at necropsy. Some may consider 6 months to be too short a period to indicate longer survival in a human patient, but maintaining immunosuppressed NHPs consistently for long periods is much more difficult than managing a patient in a hospital setting. NHPs have unhygienic habits, cannot communicate any symptoms they might be experiencing, and the sophisticated facilities of hospitals, including intensive care units, cannot be replicated in an animal facility.

What do we need to do to provide these relevant experimental data to the regulatory authorities?

2. Search strategy and selection criteria

Data for this Review were identified by searches of MEDLINE, Current Contents, PubMed, and references from relevant articles using the search terms “xenotransplantation”, “kidney”, “pig”, and “nonhuman primate”. With few exceptions, only articles published in English between 1990 and 2021 were included.

3. The preclinical model

3.1. The recipient NHP

Baboons and other Old World monkeys (e.g., rhesus, cynomolgus) are currently being used experimentally as recipients of pig organ grafts. There is no conclusive evidence that one of these species provides any immunological advantage over others.

3.2. The organ-source pig

Two major topics need to be considered, namely (i) what (currently-available) genetic modifications are optimal to reduce the possibility of rejection of the graft, and (ii) what steps need to be taken to minimize the risk of the transfer of an infectious microorganism with the graft to the immunosuppressed recipient, and possibly into the community.

There has been an evolution of techniques for the genetic engineering of pigs during the past 3 decades (Table 1). A wide range of genetically-engineered pigs has been provided or proposed as organ-sources for experimental studies (Table 2), thus making results between studies (or even within a single study) difficult to compare. It is time for the optimal genetically-engineered organ-source pig (given our present knowledge) to be identified, and only organs from these specific pigs transplanted. The exact phenotype of the pig should be confirmed in vitro before an in vivo study is carried out [10].

Table 1.

Timeline for application of evolving techniques for genetic engineering of pigs employed in xenotransplantation.

| Year | Technique |

|---|---|

| 1992 | Microinjection of randomly-integrating transgenes |

| 2000 | Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) |

| 2002 | Homologous recombination |

| 2011 | Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) |

| 2013 | Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) |

| 2014 | CRISPR/Cas9* |

*CRISPR/Cas9 = clustered randomly interspaced short palindromic repeats and the associated protein 9.

Table 2.

Selected genetically-modified pigs produced for xenotransplantation research*.

| Antigen (omit 'or')deletion or ‘masking’ |

|---|

| human H-transferase gene expression (expression of blood type O antigen) |

| endo-beta-galactosidase C (reduction of Gal antigen expression) |

| α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GTKO) |

| cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) gene-knockout (NeuGc-KO) |

| β4GalNT2 (β1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase) gene-knockout (β4GalNT2-KO) |

| Complement regulation by human complement-regulatory gene expression |

| CD46 (membrane cofactor protein) |

| CD55 (decay-accelerating factor) |

| CD59 (protectin or membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis) |

| Anticoagulation and anti-inflammatory gene expression or deletion |

| von Willebrand factor (vWF)-deficient (natural mutant) |

| human tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) |

| human thrombomodulin |

| human endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) |

| human CD39 (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1) |

| Anticoagulation, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic gene expression |

| human A20 (tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 3) |

| human heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) |

| Inhibition of phagocytosis |

| human CD47 (species-specific interaction with SIRPα inhibits phagocytosis) |

| porcine asialoglycoprotein receptor 1 gene-knockout (ASGR1-KO) (decreases platelet phagocytosis) |

| human signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) (decreases platelet phagocytosis by ‘self’ recognition) |

|

Suppression of cellular immune response by gene expression or downregulation |

| CIITA-DN (MHC class II transactivator knockdown, resulting in swine leukocyte antigen class II knockdown) |

| Class I MHC-knockout (MHC-I-KO) |

| HLA-E/human β2-microglobulin (inhibits human natural killer cell cytotoxicity) |

| HLA-G |

| human FAS ligand (CD95L) |

| human GnT-III (N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III) gene |

| porcine CTLA4-Ig (Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 or CD152) |

| human TRAIL (tumor necrosis factor-alpha-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) |

| Programed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) |

| Prevention of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) activation |

| PERV siRNA |

| PERV-KO |

*Based on an original list compiled by Ekser B24.

It needs to be borne in mind that the regulatory authorities will expect a justification for each genetic manipulation included, and it should also be realized that each genetic manipulation brings with it a potential risk of introducing new problems, and thus may be detrimental to progress. For the first clinical trials, therefore, as long as they are effective in protecting the graft from the primate innate immune response, the fewer the number of genetic manipulations maybe the better.

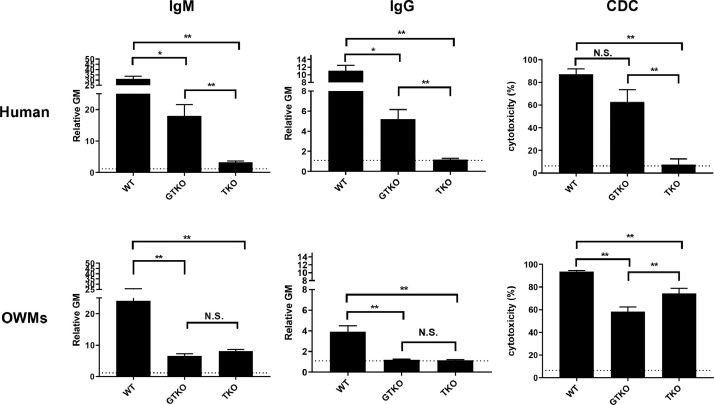

Currently, most groups agree that deletion of expression of the three known carbohydrate xenoantigens expressed in pigs against which humans have natural (preformed) antibodies (Gal, Neu5Gc, Sda, i.e., triple-knockout (TKO) pigs [Table 3]) [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16] will be important for any clinical trial. Human infants do not make natural antibodies against TKO pig cells [17], and even many adults do not have antibodies against these cells (Fig. 1). However, experimental studies are greatly complicated by the fact that all NHPs have natural antibodies to TKO pig cells [16,18]. Furthermore, these antibodies in NHPs are associated with a very high level of complement-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. 1) [18].

Table 3.

Carbohydrate xenoantigens that have been deleted in genetically-engineered pigs.

| Carbohydrate (Abbreviation) | Responsible enzyme | Gene-knockout pig |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Galactose-α1,3-galactose (Gal) |

α1,3-galactosyltransferase | GTKO |

| 2. N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) |

Cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) |

CMAH-KO |

| 3. Sda | β-1,4N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase | β4GalNT2-KO |

Fig. 1.

Human (top) and Old World monkey (OWM) (bottom) IgM (left) and IgG (middle) binding and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC, at 25% serum concentration) (right) to wild-type (WT), GTKO, and TKO pig PBMCs. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; N.S. = not significant). On the y axis, the dotted line represents cut-off value of binding (relative GM: IgM 1.2, IgG 1.1), below which there is no binding. For CDC on the y axis, the dotted line represents cut-off value of cytotoxicity (6.4%), below which there is no cytotoxicity. (Note the difference in scale on the y axis between IgM and IgG.) (Reprinted with permission from Yamamoto T, et al. 202018).

Some investigators believe that organs from TKO pigs may alone be sufficient for the first clinical trial, but we suggest that the graft may still be at risk from complement injury associated with such events as ischaemia-reperfusion or a systemic infection, or other factors, and so it would seem wise for the graft to express one or more human complement-regulatory proteins, e.g., CD46, CD55, CD59, which are largely effective in protecting a pig graft from the effects of human complement [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24].

The well-described incompatibilities in the coagulation systems between pigs and primates, highlighted originally by the groups of Platt [25], Robson [26,27], d'Apice [28,29], and others [30–32], also suggest that expression of at least one human coagulation-regulatory protein (e.g., thrombomodulin [TBM], endothelial protein C receptor [EPCR], tissue factor pathway inhibitor [TFPI]) is beneficial in NHPs in preventing the development of thrombotic microangiopathy in the graft and consumptive coagulopathy in the recipient [33,34].

The increasing evidence for a sustained systemic inflammatory response to the graft [35] suggests that expression of one or more human anti-inflammatory (anti-apoptotic) proteins, e.g., haemeoxygenase-1, A20, may also be advantageous [34]. There is also evidence that inhibition of the human macrophage response to pig cells by the expression of human CD47 in the organ-source pig may be beneficial [34].

There are several other genetic manipulations that could be included (Table 2), but many of these relate to reducing the effect of the adaptive immune response, rather than the innate response. The adaptive response can generally be suppressed by an effective immunosuppressive regimen (see below), and therefore additional genetic-engineering directed to this response may not be essential to demonstrate efficacy in the first clinical trials. Further manipulations could include knockout or knockdown of expression of swine leukocyte antigens (SLA) class I and/or II, and expression of CTLA4-Ig or PD-L1 in the graft, any of which would likely reduce the strength of the adaptive immune response, but may be associated with features of immunodeficiency in the pig [36] or possibly a susceptibility to infectious complications, e.g., of herpesviruses, in the pig organ graft itself.

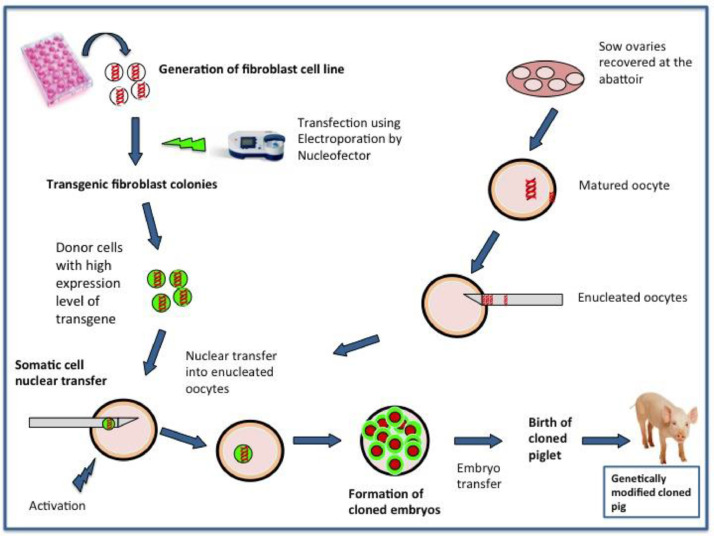

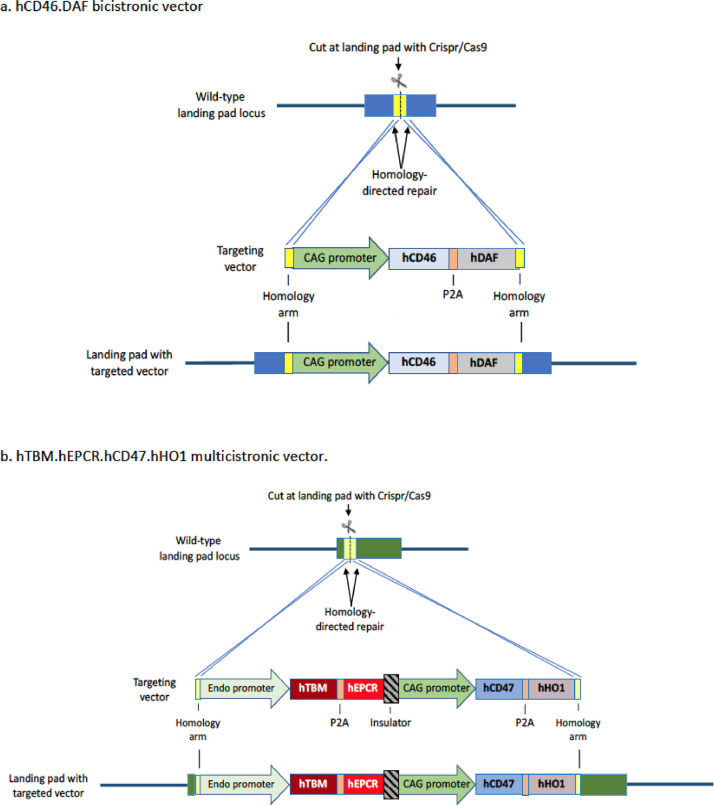

The technique of genetic-engineering of the pigs is obviously very important, e.g., with regard to whether a ubiquitous or endospecific promoter is used, and whether bicistronic or multicistronic vectors are employed [37] (Figs. 2 and 3). It is important that a human transgene should be well-expressed, but over-expression can result in complications, e.g., a bleeding tendency in the pig if expression of human coagulation-regulatory proteins is excessive.

Fig. 2.

Steps involved in somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). (Reprinted with permission from Eyestone W et al, 202037).

Fig. 3.

Design and targeting of multicistronic vectors (MCVs). CRISPR/Cas9 is designed to cut within an expression-permissive landing pad. Homology arms direct vector insertion to the landing pad by homology-directed repair. The CAG promoter is used to drive ubiquitous transgene expression (a and b) while one of several ‘endo promoters’ is used to obtain endothelial-specific expression (b). (Reprinted with permission from Eyestone W et al, 202037).

There are several other areas where genetic engineering of the pig may play a role. Two of these are of particular interest.

As the potential risks of the presence of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) in the pig remain unknown (though likely low), inactivation of these viruses [38,39], or inhibition of expression of PERV [40,41], is clearly an advantage. Such a genetic manipulation would remove the long-standing concern that PERVs may be pathogenic in humans, or may combine with fragments of human endogenous retroviruses to form new viruses. To our knowledge, to date only one group is combining PERV-knockout with the genetic manipulations required to resist the innate immune response [38].

After life-supporting pig kidney (or heart) transplantation in baboons, rapid growth of the organ has been documented within the first few months, suggesting that innate factors, e.g., a persistence of pig growth hormone, remain functioning in the graft during this period of time. After approximately 3 months, this rapid growth declines and subsequent growth of the organ is comparable to that of the native baboon organs [3,33,42–44]. Although in our experience a rapidly-growing pig kidney can be accommodated within the flexible confines of the recipient abdomen (possibly because rapamycin, which inhibits growth, is a constituent of the immunosuppressive regimen we administer) [33,43], one group has reported ischaemic injury associated with compression of the kidney graft within the abdomen [45,46].

The experiments in which this problem has been observed have used genetically-engineered domestic pigs, e.g., Large White/Landrace, as the source of the organs. If a breed of miniature swine, e.g., Yucatan, were the source, the problem might be prevented or minimized. However, minipigs, and especially Yucatan, may be characterized by high expression of PERV in different organs [47,48]. An alternative approach, suggested by Hinrichs et al. [49], [50], [51], is to delete expression of growth hormone receptors in the pig. This has been carried out [51].

4. The immunosuppressive regimen

It is important that forthcoming preclinical experience is directly relevant to the first clinical trials. Most groups have followed the lead set by Buhler et al by combining T cell depletion with blockade of the CD40/CD154 costimulation pathway (Table 4) [52,53]. Conventional maintenance immunosuppressive therapy, e.g., tacrolimus-based, has proven insufficient in pig organ xenotransplantation [52,54], and blockade of the CD28/B7 costimulation pathway has also been unsuccessful [54,55]. The current evidence is that CD40/CD154 costimulation pathway blockade is not associated with a greater incidence of drug-related complications than conventional immunosuppressive therapy.

Table 4.

A representative immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, and adjunctive drug regimen used in pig-to-baboon kidney transplantation experiments at our center.

| Agent | Dose (duration) |

|---|---|

| Induction | |

| Thymoglobulin (ATG) (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) | 5 mg/kg i.v. (days -3 and -1) (to reduce the CD3+T cell count to <500/mm3) |

|

Anti-CD20mAb (rituximab) (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) |

10 mg/kg i.v. (day -2) |

|

C1-esterase inhibitor (Berinert, CSL Behring, King of Prussia, PA) |

17.5 U/kg i.v. (days 0, 1, 7 and 14) |

| Maintenance | |

|

Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (2C10R4, a chimeric rhesus IgG4) (NIH NHP Resource Center, Boston, MA) |

50 mg/kg (days -1, 0, 4, 7, 14, and weekly) |

| Rapamycin (Rapa) (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) | 0.01-0.04 mg/kg i.m. × 2/d (target trough 6-10 ng/ml), beginning on day -4. |

|

Methylprednisolone (Astellas, Deerfield, IL) |

5 mg/kg/d on day 0, tapering to 0.125 mg/kg/d by day 7. |

| Anti-inflammatory | |

|

Etanercept (TNF-α antagonist) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) |

1 mg/kg (day 0), 0.5 mg/kg i.v. (days 3, 7, 10) |

| Adjunctive | |

| Aspirin (Bayer, Deland, FL) |

40 mg p.o. (alternate days), beginning on day 4. |

|

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Eisai, Woodcliff Lake, NJ) |

700 IU/d s.c., beginning of day 1. |

| Erythropoietin (Amgen) | 500 U i.v. weekly, beginning on day -4 |

| Ganciclovir (Genentech) | 5 mg/kg/d i.v., from day -4 to day 14 and when the baboon is sedated for blood draws (x2 weekly). |

|

Valganciclovir (Genentech) |

15 mg/kg/d p.o., beginning on day 15 |

|

Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (Teva, North Wales, PA) |

10 mg/kg i.v. daily, on days 4-14 |

| Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim oral suspension (Akorn, Lake Forest, IL) |

75 mg/m2 p.o x2/day. x3 weekly, beginning on day 15. |

However, the choice and sources of the agents and/or the dosages have varied [56]. Despite the expression of one or more human complement-regulatory proteins on the vascular endothelium of the pig organ, a case can be made for induction therapy with a complement inhibitor, e.g., a C1-esterase inhibitor, as initial systemic complement activation, possibly associated with ischaemia-reperfusion injury, may prove detrimental to graft outcome. There is evidence that blockade by an anti-CD154 agent (if non-thrombogenic) is associated with a better outcome than blockade by an anti-CD40 agent [57,58], but progress has been limited until recently by the unavailability of such agents. To our knowledge, though several anti-CD154 agents are currently in clinical trials for autoimmune disease [56], none of them is yet approved by the regulatory authorities. It remains uncertain whether they will be approved for clinical trials of xenotransplantation, but we suggest that preclinical studies should progress with the anticipation that one or more of the anti-CD154 agents will become approved.

This therapy is usually combined with a conventional immunosuppressive drug, e.g., mycophenolate mofetil, rapamycin, or tacrolimus, and a corticosteroid, but there is some evidence that corticosteroids may be unnecessary [59], particularly as they do not suppress the inflammatory response to a xenograft (see below) [35]. Furthermore, there is no conclusive evidence that even the secondary immunosuppressive agent, e.g., mycophenolate mofetil, is essential, as no group has hitherto relied on CD40/CD154 pathway blockade alone.

Just as each group involved in this field of research is using slightly different organ-source pigs for their studies, so are they also using slightly different immunosuppressive regimens. Comparison of the results of the studies between various investigators is therefore difficult or impossible, as there are so many variables. If satisfactory data are to be obtained for the regulatory authorities, future studies need to be more consistently focused on a specific genetically-engineered pig and a specific immunosuppressive regimen.

5. Anti-inflammatory therapy

There is convincing evidence of a systemic inflammatory response that follows pig organ transplantation in a NHP [35], and this is another topic that requires decisions. Is anti-inflammatory therapy necessary? There is no definite answer to this question as yet, in part because this therapy has been added to various immunosuppressive regimens and administered to NHPs receiving grafts from different genetically-engineered pigs. Without confirmatory evidence of benefit, agents such as TNF inhibitors, e.g., etanercept, and IL-6 inhibitors, e.g., tocilizumab (that prevents IL-6 binding to baboon tissues, but not to pig tissues [60]) have sometimes been included in the regimen. Conclusive evidence for their benefit needs to be provided.

6. Adjunctive therapy

Because of the high risk of the development of thrombotic microangiopathy and consumptive coagulopathy seen in the early days of research into xenotransplantation [31,32], some groups administer anti-platelet therapy and/or systemic anticoagulation to the recipient throughout part or all of the post-transplant period. Whether this is necessary if the graft expresses one or more human coagulation-regulatory proteins remains unknown, although probably neither therapy is detrimental.

7. The potential risk of infectious complications

Before a clinical trial can be undertaken, it will be necessary to determine how the risk of transfer of an exogenous infectious agent with the pig organ can be minimized. This will largely be achieved by breeding and maintaining ‘designated pathogen-free’ pigs [61] in a biosecure ‘super-clean’ facility [62]. Based on experience in immunosuppressed humans undergoing organ allotransplantation, in some pig-to-NHP organ transplant studies, prophylaxis is administered to prevent NHP cytomegalovirus (CMV) activation and infection by pneumocystis (Table 4). It should be noted, however, that ganciclovir and valganciclovir are relatively ineffective against porcine CMV [63].

In our recent studies, both the recipient baboons (Michale E. Keeling Center, Bastrop, TX) and the organ-source pigs (Revivicor, Blacksburg, VA) have been bred and raised to be CMV-negative, and a strong case could be made that prophylaxis for CMV is no longer required. In clinical trials, however, the patient may be CMV-positive, and so prophylaxis to prevent activation of human CMV will probably follow current clinical practice in this respect.

8. Diagnosis of pig kidney graft rejection

Until pigs became available that expressed human coagulation-regulatory proteins, rejection of pig kidney (and heart) grafts in NHPs could be clearly diagnosed by rapid reductions in platelet count and plasma fibrinogen as thrombotic microangiopathy developed in the graft [31–34,64]. With the availability of more advanced genetically-engineered pigs as sources of the grafts, these markers of rejection are no longer valid.

Today, the clinical features of rejection of a pig kidney are similar to those seen in clinical kidney allotransplantation, namely a rise in serum creatinine, increased proteinuria, and decreased renal blood flow on ultrasound examination. This is an important advance because physicians with experience in caring for patients with a kidney allotransplant will now be able to use that experience in the management of patients with a pig kidney xenotransplant. Both episodes of rejection and hypovolemia (see below) [65] are associated with a rise in serum creatinine, but can be differentiated because, in our experience, proteinuria only increases when rejection is occurring. Changes in urine output have not proven informative.

Immunological markers are not of great value in detecting rejection after pig kidney (or heart) xenotransplantation. Increases in serum anti-pig antibodies are usually not detectable because they bind to the graft, and only become obvious when it is possible for the graft to be excised, e.g., in the case of a heterotopic (non-life-supporting) pig heart. In our experience, when an immunosuppressive regimen based on blockade of the CD40/CD154 costimulation pathway has been administered (Table 4), post-transplantation T and B cell numbers remain at 30–40% of their baseline numbers, and are non-informative with regard to the development of rejection. There is hope, however, that methods such as the detection of cell-free pig DNA using integrated PERV sequences may prove useful in monitoring graft damage/rejection [66].

There are currently no data to determine whether changes in glomerular filtration rate correlate with the onset of rejection. Because of the relative absence of good markers of rejection, needle biopsies of the graft may need to be carried out more frequently after kidney xenotransplantation than is currently necessary after allotransplantation. Histopathological features of rejection include glomerular injury and some thrombotic microangiopathy (Foote JB, et al, submitted).

9. Functional aspects of life-supporting pig kidneys in nonhuman primates

To our knowledge there have been no detailed studies of pig kidney function in a NHP recipient, but those NHPs that have survived for several months or longer have not provided evidence of major deficiencies in this respect [1,2,33,43,44]. Furthermore, as the availability of pig kidneys will ultimately be limitless, there is no reason why a patient should not be provided with two kidneys, rather than one as in allotransplantation. With two kidneys, good renal function may be sustained over a longer period of time.

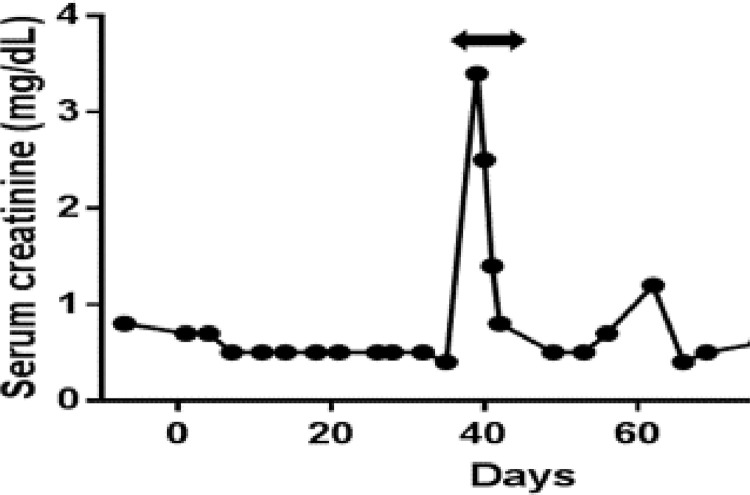

An impaired renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is one explanation for the episodes of hypovolemia that have been reported in baboons [44,65] (Fig. 4). Since decreased renin activity may be a factor, if porcine renin is confirmed not to cleave human or NHP angiotensinogen at a clinically significant rate, consideration may need to be given to generating pigs that express human renin. If other significant functional differences are identified, these could possibly also be resolved by judicious genetic engineering of the pig.

Fig. 4.

Example of a spontaneous increase in serum creatinine in a baboon with a life-supporting pig kidney transplant (with nephrectomy of the native kidneys at the time of pig kidney transplantation). The rapid reduction in creatinine to normal (human) levels was associated solely with an i.v. infusion of normal saline (arrow). A renal biospy at the time showed no features of rejection. (Reprinted with permission from Iwase H, et al, 201865).

10. The first clinical trial

Although pig-to-NHP models have provided valuable information, these models have many limitations, one of which is the presence of antibodies to TKO pig cells, as mentioned above. Another is the lack of functional receptors for PERVs in NHPs, negating the value of observations on the potential complications of PERVs in pig-to-NHP models [67]. We firmly believe that progress will advance more rapidly when clinical trials take place.

Our proposal is that the first clinical trial of pig kidney transplantation should be limited to only four carefully-selected patients over the course of one year. If, after the first transplant, the patient remains well for three months with good renal function and an absence of major complications, e.g., infection, then the second patient would be added to the trial. All four patients would be followed for one year, at which time, in collaboration with the regulatory authorities, a decision would be made on expanding the trial.

11. Selection of patients

In the USA, the median waiting time for a deceased human kidney (approximately 4 years) indicates the time it will take for half of the potential recipients to undergo kidney transplantation. Patients removed from the wait-list are not included in the calculation. Importantly, information on median wait-time obscures the fact that, because of death or being removed from the wait-list because they are no longer acceptable recipients, a significant percentage of candidates (approximately 40%) never receive an allograft.

On the basis that the period on the wait-list might be so long that they may die before being allocated a deceased human donor organ, we have suggested that older age patients (55–60 years or possibly 55-65 years), but with good physiology and no serious comorbidities, particularly if of blood group O (as these patients tend to spend longer on the wait-list), should be considered as potential candidates for the first clinical trial [69]. As the anticipated period of pig graft survival remains uncertain, younger patients, who are more likely to survive until a suitable allograft becomes available, should perhaps be excluded from the initial trials.

We suggest that the patients should have been initiated on chronic hemodialysis (and should not undergo pre-emptive kidney xenotransplantation, i.e., before requiring dialysis) because the patient and his/her family should be convinced that kidney failure has progressed to the point where death would have occurred if dialysis had not been initiated. Other factors could also be considered, e.g., patients (i) who no longer have vascular access to enable hemodialysis, or (ii) with recurrent kidney disease after allotransplantation, but we suggest that these patients are less suitable because they have likely been on dialysis for a long period of time (and, therefore, have possibly developed comorbidities) and/or have undergone previous kidney allotransplantation, both of which conditions might complicate the management of the patient in an initial clinical trial. With few differences, exclusion criteria for the first patients should be based on those for selection for allotransplantation, and have been documented elsewhere [68].

12. Immunologic aspects of patient selection

Potential human recipients should be selected who do not have (i) anti-glycan IgM/IgG (i.e., anti-TKO pig) antibodies or evidence of serum cytotoxicity to cells from the organ-source pig, (ii) antibodies directed to human leukocyte antigens (i.e., anti-HLA antibodies) that may cross-react with swine leukocyte antigens [SLA]), and (iii) a particularly strong response on mixed lymphocyte reaction (compared to the median response of a panel of potential recipients) [69].

Patients with high calculated panel-reactive antibodies (cPRA) (i.e., anti-HLA antibodies), for whom it will be difficult to identify an acceptable deceased human donor, will be strong future candidates for xenotransplantation. However, although the majority of HLA-sensitized patients do not appear to have antibodies that cross-react with SLA [70], [71], [72], there is evidence that some do, which would increase the risk of antibody-mediated rejection of the pig organ [73,74]. A very recent study suggested that pig kidney graft survival was shorter in allosensitized monkeys than in non-sensitized monkeys [75].

Studies by Martens, Ladowski, and their colleagues indicated that sera from some sensitized humans may possess cross-reactive anti-HLA antibodies capable of binding to SLA in epitope-restricted patterns [74,76,77]. Importantly, single amino-acid mutagenesis of the HLA-SLA epitope by genetic engineering, for example mutation of an arginine to a proline in the SLA molecule, significantly decreased or completely eliminated antibody binding for a majority of tested samples [76,77]. However, there are exceptions to this approach. For one SLA class II epitope, the antibody binding was limited to the epitope, and was unchanged despite mutations made to the surrounding amino acids [77].

Although HLA-sensitized patients may ultimately benefit most from the availability of pig kidney xenografts, we suggest that they should not be considered for the first clinical trial. However, the novel methods of genetic engineering being explored offer the prospect of overcoming this problem in the future, enabling even HLA-highly-sensitized patients to undergo xenotransplantation with no additional risk of graft rejection.

The current (limited, but increasing) evidence suggests that sensitization to pig antigens, should it develop after pig organ transplantation, would not be detrimental to the outcome of a subsequent allotransplant [78,79]. If confirmed, this is a very important point as it would not preclude subsequent successful allotransplantation after an initial bridging xenotransplant. A patient undergoing pig kidney transplantation could remain on the wait-list for a deceased human allograft and, at least for a period of time (as yet uncertain), avoid the medical and social disadvantages of chronic dialysis, and enjoy the benefits of a functioning kidney graft. The experience gained by such a clinical trial would provide valuable data that would enable progression to pig kidney transplantation as destination therapy.

13. Public opinion

Ethical and social aspects of xenotransplantation also need to be considered. The opinions of patients, health care professionals, and members of the public need to be sought. A number of surveys and focus groups have been organized by Paris and his colleagues during the past three years, which indicate that the public is largely supportive of xenotransplantation [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86]. The influence of religious beliefs has also been explored [87,88].

14. Conclusions

Although data regarding genetically-engineered pig kidney transplantation in NHPs are steadily accumulating, numerous details need to be clarified before the regulatory authorities can be provided with definitive data to support a clinical trial of xenotransplantation. The two most important areas that need attention are (i) what pig genetics are necessary, and (ii) what immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory/adjunctive therapeutic regimen is optimal to offer success. Decisions will be based on current and future experience in the laboratory, but must be applicable to clinical xenotransplantation.

Outstanding questions

The most important are (i) what genetic manipulations in the pig are considered essential or highly beneficial to protect against the innate immune response, and (ii) what drug therapy is necessary for the recipient to prevent the adaptive immune response.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Work on xenotransplantation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham is supported in part by NIH NIAID U19 Grant AI090959, and in part by a Department of Defense Grant W81XWH2010559.

Footnotes

(Quote by Christiaan N. Barnard, MD, the surgeon who carried out the world's first human-to-human heart transplant in 1967).

References

- 1.Adams A.B., Kim S.C., Martens G.R. Xenoantigen deletion and chemical immunosuppression can prolong renal xenograft survival. Ann Surg. 2018;268:564–573. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S.C., Mathews D.V., Breeden C.P. Long-term survival of pig-to-rhesus macaque renal xenografts is dependent on CD4 T cell depletion. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2174–2185. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langin M., Mayr T., Reichart B. Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature. 2018;564:430–433. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0765-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleveland D.C., Jagdale A., Carlo W.F. The genetically engineered heart as a bridge to allotransplantation in infants: just around the corner? Ann Thorac Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.05.025. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper D.K.C. The case for xenotransplantation. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:288–293. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starzl T.E. History of clinical transplantation. World J Surg. 2000;24:759–782. doi: 10.1007/s002680010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins R.C., Barlow C.W., Oyer P.E. Thirty years of cardiac transplantation at Stanford university. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:939–951. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper D.K.C. Christiaan Barnard and his contributions to heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper D.K.C., Cleveland DC. The first clinical trial – kidney or heart? Xenotransplantation. 2020:e12644. doi: 10.1111/xen.12644. Dec18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li P., Walsh J.R., Lopez K. Genetic engineering of porcine endothelial cell lines for evaluation of human-to-pig xeno reactive immune responses. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Good A.H., Cooper D.K.C., Malcolm A.J. Identification of carbohydrate structures that bind human antiporcine antibodies: implications for discordant xenografting in man. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper D.K.C., Koren E., Oriol R. Genetically engineered pigs. Lancet. 1993;342:682–683. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91791-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phelps C.J., Koike C., Vaught T.D. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouhours D., Pourcel C., Bouhours J.E. Simultaneous expression by porcine aorta endothelial cells of glycosphingolipids bearing the major epitope for human xenoreactive antibodies (gal alpha 1-3gal), blood group h determinant and n-glycolylneuraminic acid. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:947–953. doi: 10.1007/BF01053190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrne G.W., Du Z., Stalboerger P., Kogelberg H., McGregor C.G. Cloning and expression of porcine beta1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase encoding a new xenoreactive antigen. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:543–554. doi: 10.1111/xen.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrada J.L., Martens G., Li P., Adams A. Evaluation of human and non-human primate antibody binding to pig cells lacking GGTA1/CMAH/beta4GALNT2 genes. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:194–202. doi: 10.1111/xen.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q., Hara H., Banks C.A. Anti-pig antibody levels in infants: can a genetically-engineered pig heart bridge to allotransplantation? Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:1268–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T., Iwase H., Patel D. Old World monkeys are less than ideal transplantation models for testing pig organs lacking three carbohydrate antigens (triple-knockout) Sci Rep. 2020;10:9771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66311-3. Jun 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson J.P., Oglesby T.J., White D., Adams E.A., Liszewski M.K. Separation of self from non-self in the complement system: a role for membrane cofactor protein and decay accelerating factor. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;86(Suppl 1):27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb06203.x. 19v91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalmasso A.P., Vercellotti G.M., Platt J.L., Bach F.H. Inhibition of complement-mediated endothelial cell cytotoxicity by decay-accelerating factor. Potential for prevention of xenograft hyperacute rejection. Transplantation. 1991;52:530–533. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199109000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White D.J., Oglesby T., Liszewski M.K. Expression of human decay accelerating factor or membrane cofactor protein genes on mouse cells inhibits lysis by human complement. Transpl Int. 1992;5(suppl 1):S648–S650. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77423-2_190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White D.J.G., Langford G.A., Cozzi E. Production of pigs transgenic for human DAF: a strategy for xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 1995;2:213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cozzi E., White D.J. The generation of transgenic pigs as potential organ donors for humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:964–966. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper D.K.C., Ekser B., Ramsoondar J., Phelps C., Ayares D. The role of genetically-engineered pigs in xenotransplantation research. J Pathol. 2015;238:288–299. doi: 10.1002/path.4635. Sep 142016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawson J.H., Daniels L.J., Platt J.L. The evaluation of thrombomodulin activity in porcine to human xenotransplantation. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:884–885. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp C.W., Grey S.T., Siegel J.B. Expression of human thrombomodulin cofactor activity in porcine endothelial cells. Transplantation. 1998;66:244–251. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199807270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robson S.C., Cooper D.K.C., d'Apice A.J. Disordered regulation of coagulation and platelet activation in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:166–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.d'Apice A.J., Cowan P.J. Profound coagulopathy associated with pig-to-primate xenotransplants: how many transgenes will be required to overcome this new barrier? Transplantation. 2000;70:1273–1274. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowan P.J., Aminian A., Barlow H. Renal xenografts from triple-transgenic pigs are not hyperacutely rejected but cause coagulopathy in non-immunosuppressed baboons. Transplantation. 2000;69:2504–2515. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozlowski T., Shimizu A., Lambrigts D. Porcine kidney and heart transplantation in baboons undergoing a tolerance induction regimen and antibody adsorption. Transplantation. 1999;67:18–30. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bühler L., Basker M., Alwayn I.P.J. Coagulation and thrombotic disorders associated with pig organ and hematopoietic cell transplantation in nonhuman primates. Transplantation. 2000;70:1323–1331. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knosalla C., Gollackner B., Bühler L. Correlation of biochemical and hematological changes with graft failure following pig heart and kidney transplantation in baboons. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1510–1519. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwase H., Hara H., Ezzelarab M. Immunological and physiologic observations in baboons with life-supporting genetically-engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24 doi: 10.1111/xen.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper D.K.C., Hara H., Iwase H. Justification of specific genetic modifications in pigs for clinical kidney or heart xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2019:e12516. doi: 10.1111/xen.12516. Apr 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ezzelarab M.B., Ekser B., Azimzadeh A. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients precedes activation of coagulation. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:32–47. doi: 10.1111/xen.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phelps C.J., Ball S.F., Vaught T.D. Production and characterization of transgenic pigs expressing porcine CTLA4-Ig. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:477–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyestone W., Adams K., Ball S. In: Clinical xenotransplantation: pathways and progress in the transplantation of organs and tissues between species. Cooper DKC, Byrne GW, editors. Springer; New York: 2020. Gene-edited pigs for xenotransplantation; pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu D., Wei H.J., Lin L. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2017;357:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godehardt A.W., Fischer N., Rauch P. Characterization of porcine endogenous retrovirus particles released by the CRISPR/Cas9 inactivated cell line PK15 clone 15. Xenotransplantation. 2020;27(2):e12563. doi: 10.1111/xen.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dieckhoff B., Petersen B., Kues W.A. Knockdown of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) expression by PERV-specific shRNA in transgenic pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsoondar J., Vaught T., Ball S. Production of transgenic pigs that express porcine endogenous retrovirus small interfering RNAs. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soin B., Ostlie D., Cozzi E. Growth of porcine kidneys in their native and xenograft environment. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:96–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwase H., Liu H., Wijkstrom M. Pig kidney graft survival in a baboon for 136 days: longest life-supporting organ graft survival to date. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:302–309. doi: 10.1111/xen.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwase H., Klein E., Cooper DKC. Physiologic aspects of pig kidney transplantation in nonhuman primates. Comp Med. 2018;68:332–340. doi: 10.30802/AALAS-CM-17-000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah J.A., Tanabe T., Yamada K. Role of intrinsic factors in the growth of transplanted organs following transplantation. J Immunobiol. 2017;2:122. doi: 10.4172/2476-1966. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanabe T., Watanabe H., Shah J.A. Role of intrinsic (graft) versus extrinsic (host) factors in the growth of transplanted organs following allogeneic and xenogeneic transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1778–1790. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dieckhoff B., Kessler B., Jobst D. Distribution and expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses in multi-transgenic pigs generated for xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bittmann I., Mihica D., Plesker R., Denner J. Expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) in different organs of a pig. Virology. 2012;433:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinrichs A., Kessler B., Kurome M. Growth hormone receptor-deficient pigs resemble the pathophysiology of human Laron syndrome and reveal altered activation of signaling cascades in the liver. Mol Metab. 2018;11:113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hinrichs A., Klymiuk N., Dahlhoff M. Growth hormone receptor knockout in GTKO/hCD46/hTM pigs as a strategy to prevent overgrowth of orthotopic xeno- hearts in baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2019;26:e12553. Abstract 225.3. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iwase H., Ball S., Adams W.T., Eyestone W., Walter A., Cooper DKC. Growth hormone receptor knockout: relevance to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2020 Oct 14:e12652. doi: 10.1111/xen.12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bühler L., Awwad M., Basker M. High-dose porcine hematopoietic cell transplantation combined with CD40 ligand blockade in baboons prevents an induced anti-pig humoral response. Transplantation. 2000;69:2296–2304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samy K., Butler J., Li P., Cooper D.K.C., Ekser B. The role of costimulation blockade in solid organ and islet xenotransplantation. J Immunol Res. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/8415205. Corrigendum J Immunol Res 2018;2018: doi.org/10.1155/2018/6343608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto T., Hara H., Foote J. Life-supporting kidney xenotransplantation from genetically-engineered pigs in baboons: a comparison of two immunosuppressive regimens. Transplantation. 2019;103:2090–2104. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwase H., Ekser B., Satyananda V. Pig-to-baboon heterotopic heart transplantation-exploratory preliminary experience with pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin and comparison of three costimulation blockade-based regimens. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:211–220. doi: 10.1111/xen.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bikhet M.H., Iwase H., Yamamoto T. What therapeutic regimen will be optimal for initial clinical trials of pig organ transplantation? Transplantation. 2021 Jan 27 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003622. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin J.S., Kim J.M., Kim J.S. Long-term control of diabetes in immunosuppressed nonhuman primates (NHP) by the transplantation of adult porcine islets. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2837–2858. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin J.S., Kim J.M., Min B.H. Pre-clinical results in pig-to-non-human primate islet xenotransplantation using anti-CD40 antibody (2C10R4)-based immunosuppression. Xenotransplantation. 2018;25(1) doi: 10.1111/xen.12356. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada K., Yazawa K., Shimizu A. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of α1,3- galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2005;11:32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang G., Iwase H., Wang L. Is interleukin-6 receptor blockade (tocilizumab) beneficial or detrimental to pig-to-baboon organ xenotransplantation? Am J Transplant. 2020;20:999–1013. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fishman J.A. Prevention of infection in xenotransplantation: designated pathogen-free swine in the safety equation. Xenotransplantation. 2020;27:e12595. doi: 10.1111/xen.12595. doc:10/1111/xen.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kraebber K., Gray E. In: Clinical xenotransplantation: pathways and progress in the transplantation of organs and tissues between species. Cooper DKC, Byrne GW, editors. Springer; New York: 2020. Addressing regulatory requirements for the organ-source pig – a pragmatic approach to facility design and pathogen prevention; pp. 144–153. pp. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mueller N.J., Sulling K., Gollackner B. Reduced efficacy of ganciclovir against porcine and baboon cytomegalovirus in pig-to-baboon xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1057–1064. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper D.K.C., Ezzelarab M.B., Hara H. The pathobiology of pig-to-primate xenotransplantation: a historical review. Xenotransplantation. 2016;23:83–105. doi: 10.1111/xen.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iwase H., Yamamoto T., Cooper D.K.C. Episodes of hypovolemia/dehydration in baboons with pig kidney transplants: a new syndrome of clinical importance? Xenotransplantation. 2018:e12472. doi: 10.1111/xen.12472. Nov 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Denner J. Detection of cell-free pig DNA using integrated PERV sequences to monitor xenotransplant tissue damage and rejection. Xenotransplantation. 2021:e12688. doi: 10.1111/xen.12688. Mar 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Denner J. Why was PERV not transmitted during preclinical and clinical xenotransplantation trials and after inoculation of animals? Retrovirology. 2018;15(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12977-018-0411-8. Apr 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jagdale A., Kumar V., Anderson D.J. Suggested patient selection criteria for initial clinical trials of pig kidney xenotransplantation in the USA. Transplantation. 2021 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003622. Jan 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucander A.C.K., Hara H., Nguyen H.Q., Foote J.B., Cooper DKC. Immunological selection and monitoring of patients undergoing pig kidney transplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2021 doi: 10.1111/xen.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hara H., Ezzelarab M., Rood P.P. Allosensitized humans are at no greater risk of humoral rejection of GT-KO pig organs than other humans. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong B.S., Yamada K., Okumi M. Allosensitization does not increase the risk of xenoreactivity to α1,3-Galactosyltransferase gene-knockout miniature swine in patients on transplantation waiting lists. Transplantation. 2006;82:314–319. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000228907.12073.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Z., Hara H., Long C. Immune responses of HLA-highly-sensitized and non-sensitized patients to genetically engineered pig cells. Transplantation. 2018;102:e195–e204. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martens G.R., Reyes L.M., Li P. Humoral reactivity of renal transplant-waitlisted patients to cells from GGTA1/CMAH/B4GalNT2, and SLA class I knockout pigs. Transplantation. 2017;101:e86–e92. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martens G.R., Ladowski J.M., Estrada J. HLA class I-sensitized renal transplant patients have antibody binding to SLA class I epitopes. Transplantation. 2019;103:1620–1629. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Olaso D., Manook M., Yoon J. Impact of allosensitization on xenosensitization. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(suppl 3) https://atcmeetingabstracts.com/abstract/impact-of-allsensitization-on-xenotransplantation/ abstract Accessed June 292021. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ladowski J.M., Martens G.R., Reyes L.M. Examining the biosynthesis and xenoantigenicity of class II swine leukocyte antigen proteins. J Immunol. 2018;200:2957–2964. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ladowski J.M., Martens G.R., Reyes L.M. Examining epitope mutagenesis as a strategy to reduce and eliminate human antibody binding to class II swine leukocyte antigens. Immunogenetics. 2019;71:479–487. doi: 10.1007/s00251-019-01123-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Q., Hara H., Zhang Z., Breimer M.E., Wang Y., Cooper D.K.C. Is sensitization to pig antigens detrimental to subsequent allotransplantation? Xenotransplantation. 2018;25:e12393. doi: 10.1111/xen.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hara H., Nguyen H.Q., Wang Z.Y. Evidence that sensitization to triple-knockout pig cells will not be detrimental to subsequent allotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2021;30:e12701. doi: 10.1111/xen.12701. May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paris W., Mitchell C., Werkheiser Z., Lipps A., Cooper D.K.C., Padilla L. In: Clinical xenotransplantation: pathways and progress in the transplantation of organs and tissues between species. Cooper DKC, Byrne GW, editors. Springer; New York: 2020. Public perspectives towards clinical trials of organ xenotransplantation; pp. 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Padilla L.A., Hurst D., Lopez R., Kumar V., Cooper D.K.C., Paris W. Attitudes to clinical pig kidney xenotransplantation among medical providers and patients. Kidney360. 2020;1:657–662. doi: 10.34067/KID.0002082020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Padilla L.A., Hurst D.J., Jang K. Racial differences in attitudes to clinical pig organ xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2021;28(2):e12656. doi: 10.1111/xen.12656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Padilla L.A., Hurst D.J., Jang K., Bargainer R., Cooper D.K.C., Paris W. Acceptance of xenotransplantation among nursing students. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2021 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mitchell C., Lipps A., Padilla L., Werkheiser Z., Cooper D.K.C., Paris W. Meta-analysis of public perception toward xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2020;27(4):e12583. doi: 10.1111/xen.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hurst D.J., Padilla L.A., Cooper D.K.C., Paris W. Factors influencing attitudes toward xenotransplantation clinical trials: a report of focus group studies. Xenotransplantation. 2021:e12684. doi: 10.1111/xen.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hurst D.J., Padilla L., Pollio D., Cooper D.K.C., Paris W. The attitudes of religious group leaders towards xenotransplantation: a focus group study. Submitted. 2021 doi: 10.1111/xen.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paris W., Seidler R.J.H., FitzGerald K., Padela A.I., Cozzi E., Jewish C.D.K.C. Christian and Muslim theological perspectives about xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2018;25(3):e12400. doi: 10.1111/xen.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ebner K., Ostheimer J., Sautermeister J. The role of religious beliefs for the acceptance of xenotransplantation. Exploring dimensions of xenotransplantation in the field of hospital chaplaincy. Xenotransplantation. 2020;27(4):e12579. doi: 10.1111/xen.12579. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]