Abstract

Mammalian cell extracts have been shown to carry out damage-specific DNA repair synthesis induced by a variety of lesions, including those created by UV and cisplatin. Here, we show that a single psoralen interstrand cross-link induces DNA synthesis in both the damaged plasmid and a second homologous unmodified plasmid coincubated in the extract. The presence of the second plasmid strongly stimulates repair synthesis in the cross-linked plasmid. Heterologous DNAs also stimulate repair synthesis to variable extents. Psoralen monoadducts and double-strand breaks do not induce repair synthesis in the unmodified plasmid, indicating that such incorporation is specific to interstrand cross-links. This induced repair synthesis is consistent with previous evidence indicating a recombinational mode of repair for interstrand cross-links. DNA synthesis is compromised in extracts from mutants (deficient in ERCC1, XPF, XRCC2, and XRCC3) which are all sensitive to DNA cross-linking agents but is normal in extracts from mutants (XP-A, XP-C, and XP-G) which are much less sensitive. Extracts from Fanconi anemia cells exhibit an intermediate to wild-type level of activity dependent upon the complementation group. The DNA synthesis deficit in ERCC1- and XPF-deficient extracts is restored by addition of purified ERCC1-XPF heterodimer. This system provides a biochemical assay for investigating mechanisms of interstrand cross-link repair and should also facilitate the identification and functional characterization of cellular proteins involved in repair of these lesions.

DNA interstrand cross-linking agents are among the oldest and yet still most effective anticancer drugs available in the clinic, and the chemotherapeutic use of the early forms of these chemicals, such as mustard gas and nitrogen mustard, extends back to before the Second World War. The alkylation chemistry of these drugs was also elucidated shortly after that war, and their cellular pharmacology was extensively studied during the 1970s and 1980s (27). In contemporary chemotherapy, interstrand cross-linking agents such as cyclophosamide, melphalan, and cisplatin are among the most potent antitumor agents. Despite this lengthy history of clinical use and pharmacologic investigation, the mechanisms of repair of the lesions produced in DNA by interstrand cross-linking agents have not been extensively studied. This situation of relative neglect of biochemical pathways of cross-link repair contrasts with the striking advances that have been accomplished in the past decade in other DNA damage processing pathways, such as nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair, and mismatch repair (18).

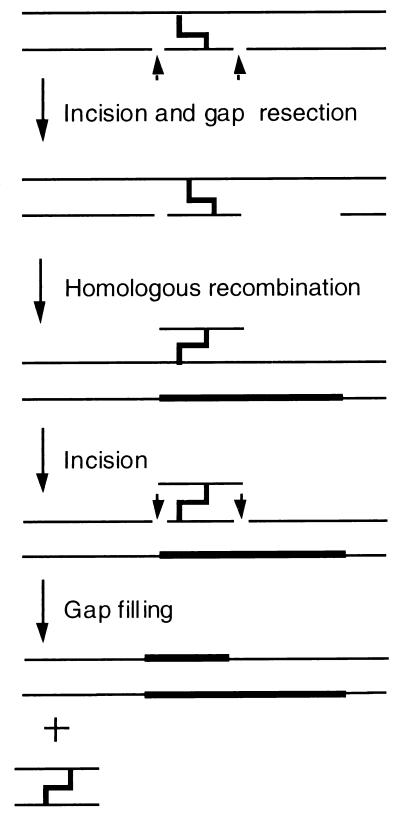

Current evidence (44) indicates that the error-free repair of both interstrand cross-links and double-strand breaks involves a recombinational mechanism in which an undamaged donor chromosome provides a homologous copy for the repair of the damaged template. Both of these lesions are highly deleterious, and it has been shown in certain yeast genetic backgrounds in which particular DNA repair pathways have been abolished that a single occurrence of either lesion in the genome is lethal (17, 34). The most extensive studies of cross-link repair have been carried out in Escherichia coli. Cole and his coworkers were the first to show that the repair of cross-link damage in E. coli depends upon the products of the uvrA, uvrB, uvrC, uvrD, recA, and polA genes (11, 12). These findings indicated that components of both NER and recombination pathways of E. coli were required for cross-link repair, and Cole et al. (12) proposed a model for the recombinational repair of interstrand cross-links in E. coli (Fig. 1). Elements of this model as well as additional insights into this pathway have been demonstrated by subsequent investigators as well. Using photoactivated psoralen as a model cross-linking agent, Sancar, Hearst, and their colleagues determined that the initial incisions made at the site of the lesion are located 9 nucleotides to the 5′ side and three nucleotides to the 3′ side (45). This same group also showed that the (A)BC exinuclease will cleave a triple-stranded cross-linked substrate which mimics the proposed intermediate shown in Fig. 1 (8, 9). Sladek et al. (40) showed that a substrate with dual incisions on either side of the cross-link did not stimulate strand exchange by RecA. However, if the nick is processed into a gap, RecA-mediated strand exchange is stimulated, suggesting that an exonucleolytic step, possibly carried out by PolI, is required prior to recombination. Taken together, these findings are strong support for a recombinational mode of interstrand cross-link repair and are consistent with Cole’s model.

FIG. 1.

Cole’s model for the recombinational repair of interstrand cross-links in E. coli.

The genetics of recombinational repair in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been well characterized (18). There are three DNA repair epistasis groups in yeast, and the RAD52 group represents recombinational repair pathways as indicated by the sensitivity of mutants within this group to ionizing radiation and/or cross-linking agents. Many members of this group are also required for both mitotic and meiotic recombination. In addition to the members of the RAD52 group, members of the RAD3 group (NER pathway) are also apparently required for interstrand cross-link repair (21, 38). However, other than RAD1 and RAD10, members of the RAD3 group are not required for double-strand break repair (20). In addition, elements of the replicative apparatus, such as RPA, RFC, PCNA, and DNA polymerases, may also be necessary for various stages of repair of interstrand cross-links.

The extensive studies in yeast have yielded a reliable genetic framework for recombinational repair pathways in eucaryotes. In mammalian systems, however, these studies are far less advanced. There are basically two series of mammalian mutants that have exhibited hypersensitivity to cross-linking agents. These are laboratory-derived mutant rodent cell lines (13) and cell lines derived from patients with the highly cancer-prone genetic disease Fanconi anemia (FA) (18). Members of both of these groups exhibit a general but varied sensitivity to cross-linking agents (2, 13). The cloning of some genes that complement these mammalian mutants has been achieved (16, 32, 33, 41); however, the biochemical mechanisms of recombinational repair of interstrand cross-links in eucaryotic systems are largely unknown. As an approach to elucidate these mechanisms, we report here our results on the development of a mammalian cell-free assay that specifically responds to the presence of interstrand cross-links in DNA. We show that a single cross-link stimulates synthesis into a damaged plasmid and into an unmodified plasmid as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and biochemicals.

Lymphoid cell lines were obtained from the Human Genetic Mutant Cell Repository (Camden, N.J.) and cultured in suspension in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. V-H4 and V-C8 cell lines and the irs1 and irs1SF cell lines were generously provided by M. Zdzienicka and N. Jones, respectively. HeLa and rodent cell lines were cultured in Joklit medium and minimal essential medium (MEM), respectively, plus 10% fetal calf serum. ERCC1-XPF protein complex was a generous gift of A. Sancar, and RPA and PCNA were generously supplied by Z.-Q. Pan.

Preparation of substrates.

For the preparation of cross-linked duplex oligonucleotide (BsrGI oligo), two complementary oligonucleotides with the following sequences were synthesized and kinased: 5′ GCTCTCGTCTGTACACCGAAG and 5′ GCTCTTCGGTGTACAGACGAG. Bold letters indicate nucleotide residues involved in the cross-link, and the underlining indicates BsrGI restriction sites. Annealing of these oligonucleotides creates the identical 3-nucleotide sticky end at both ends of the duplex. These ends can be ligated to HindIII sticky ends that have been filled in with a single dATP residue by reaction with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. One hundred micrograms of this substrate was added to 4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen at 5 μg/ml in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–0.5 mM EDTA–25 mM NaCl. The sample was irradiated with 365-nm UV light (10 min at 9 mW/cm2) to effect formation of the interstrand cross-link (10) between the internal thymines of the BsrGI site. The extent of the reaction was minimized in order to maintain an average of one adduct or less per duplex oligonucleotide. The cross-linked oligonucleotide was purified from un-cross-linked DNA by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

To begin the construction of the cross-linked template (CLT) plasmid, a duplex oligonucleotide containing a NcoI site was inserted between the two SspI sites in pBSII, and the resulting plasmid was designated pBS-Nco. To insert the cross-linked oligonucleotide, an aliquot of pBS-Nco was digested with HindIII, and a single deoxyadenine residue was added to the 3′ ends of the cleavage site by incubation with Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. This latter step which prevents self-ligation of the plasmid or the cross-linked oligonucleotide increases the efficiency of the ligation reaction. After ligation, covalently closed CLT plasmid was purified by CsCl-ethidium bromide gradient centrifugation. Ethidium bromide was quantitatively removed by repeated rounds of ion exchange chromatography. For construction of the control template (CT) and the donor template (DT) plasmids, an un-cross-linked version of the duplex oligonucleotide was cloned into the HindIII sites of the CLT plasmid and pBSII, respectively. Since the CLT contains both orientations of the duplex oligonucleotide, both orientations were also obtained in the CT and DT plasmids. These latter plasmids represent permanent constructs that were prepared in bulk quantities from host cells.

Modification of the CT plasmid with either angelicin or N-acetoxy-N-2-acetyl aminofluorene (AAAF) was performed as previously described (30, 46).

CRS assay.

Mammalian whole-cell (WC) extracts were prepared by the method of Manley et al. (36). Before being used in the cross-link repair synthesis (CRS) assay, each extract was tested for competency in the NER assay (48). Extracts that were defective in the NER assay were discarded with the exception of UV20 or xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) extracts, which are constitutively deficient in this assay. The repair reaction buffer is essentially that previously described (48). Standard 50-μl reaction mixtures contained (final concentration) 100 μg of extract, 20 to 40 ng of the CLT or CT, 100 to 150 ng of the DT, 45 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8), 75 mM KCl, 7.4 mM MgCl2, 0.9 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 mM EDTA, 2 mM ATP, 20 μM each of dATP, dGTP, and TTP, 8 μM dCTP, 2 μCi [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), 40 mM phosphocreatine, 2.5 μg of creatine phosphokinase, approximately 3% glycerol, and 18 μg of bovine serum albumin. The reaction mixtures were usually incubated for 3 h at 22°C.

After incubation, the reactions were stopped by the addition of EDTA to 20 mM. One microgram of DNase-free RNase (Boehringer Mannheim) was added, and the sample was incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added to 0.5% and proteinase K to 190 μg/ml, and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The DNA was subsequently extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with 95% ethanol–2% KAc on ice. Plasmids were then sequentially digested with BsaI (or AvaII) and NcoI under conditions recommended by the manufacturers. After gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide, the gels were photographed and subsequently dried down for autoradiography. Using intensifying screens, gels were typically exposed for 4 to 16 h at −80°C. Quantification of autoradiograms was performed by scanning autoradiograms with Adobe Photoshop software and determining band intensities with Intelligent Quantifier software (Bio Image). Each assay reported in this publication was performed a minimum of two times, and representative results are shown.

Immunodepletion of HeLa extracts.

Anti-hRad51 sera or preimmune (control) sera were adjusted to 1× TBS buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]–100 mM NaCl) and then incubated with preswollen protein A-sepharose beads for 45 min at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with TBS buffer and then incubated with 100 μg of HeLa WC extract for 2 h on ice with gentle rotation. The supernatant (hRad51-depleted extract) was recovered and subsequently examined in the CRS assay.

RESULTS

Substrates for the CRS assay.

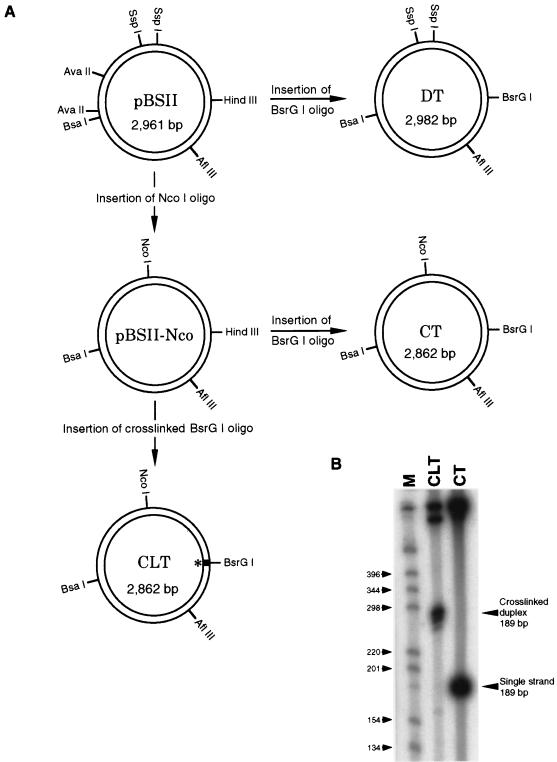

Our approach to the development of an in vitro assay for interstrand cross-link repair was to monitor damage-induced repair synthesis. Since we anticipated a recombinational mode of DNA repair, the assay required a damaged plasmid and a homologous donor plasmid that could, however, be distinguished from each other upon gel electrophoresis. With these constraints in mind, we constructed the plasmid substrates illustrated in Fig. 2A for the CRS assay. The starting material for each of the three constructs, which are referred to as the CLT, the DT, and the CT, was the pBluescriptII (pBSII) plasmid. The salient features of the CLT are the placement of a single psoralen cross-link at a unique site by the insertion of a cross-linked oligonucleotide and the addition of a restriction site (NcoI) that allows the CLT plasmid to be distinguished from the DT plasmid. The cross-linked oligonucleotide was prepared by reaction with 4,5′,8-trimethylpsoralen plus near-UV light (10) and subsequent gel purification. As shown (Fig. 2B), the typical CLT preparation contains essentially 100% cross-linked DNA with no detectable uncross-linked material. We estimate that approximately 10 to 20% of the CLT also contains psoralen monoadducts. However, as shown below, these lesions do not stimulate repair synthesis in undamaged donor plasmids. The DT plasmid is identical to the CLT plasmid except that it lacks the NcoI site and the psoralan cross-link (Fig. 2A). The CT plasmid is identical to the CLT plasmid except that it lacks the psoralen cross-link (Fig. 2A). Further details of the preparation of these substrates can be found in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 2.

Construction of plasmid substrates for the CRS assay. (A) CLT, CT, and DT represent cross-linked template, control template, and donor template, respectively. ∗, site of interstrand cross-link; oligo, oligonucleotide. (B) Purity of the CLT. An aliquot of the CLT and CT was digested with BssHII, radiolabeled, and electrophoresed through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Digestion with BssHII excises a fragment of 189 bp containing the cross-link.

CRS assay with mammalian cell extracts.

Employing the substrates described above, we evaluated various mammalian cell extracts for DNA synthesis induced by the presence of photoactivated psoralen interstrand cross-links by using incorporation of radiolabeled nucleotides as a measure of activity. We used the buffer, which includes an ATP regenerating system, that was previously described for the NER cell-free assay (48). To briefly summarize these results, both WC (37) and nuclear (14) extracts yielded results indicating that DNA synthesis induced by interstrand cross-links occurred in these extracts. However, more consistent results were obtained with WC extracts, and all the experiments reported here were carried out with these extracts. Cytoplasmic extracts, prepared as described previously (31), exhibited little evidence of damage-specific DNA synthesis.

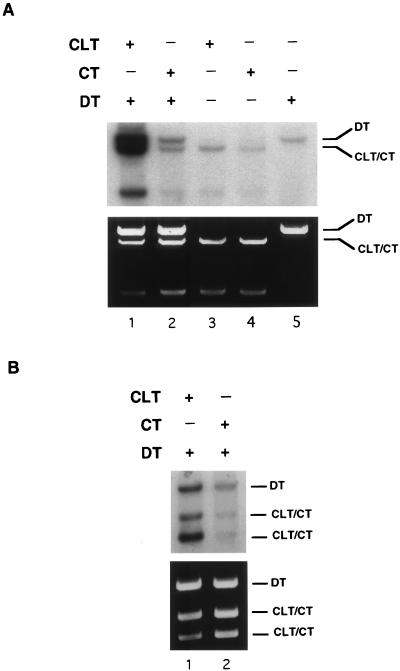

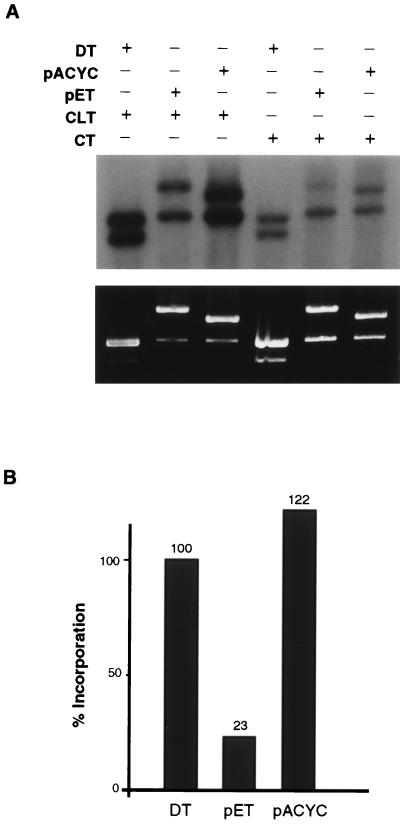

Shown in Fig. 3A is an example of CRS assay results obtained with HeLa WC extracts. After incubation in the extract, the DNAs were extracted and subsequently digested with NcoI and BsaI. Since the NcoI site is unique to the CLT and CT plasmids, this digestion allowed the CLT-CT and DT plasmids to be resolved by gel electrophoresis. As shown (Fig. 3A, lane 1), coincubation of the CLT and DT resulted in an approximately 20- to 30-fold increase in the level of incorporation compared to the coincubation of the CT and DT plasmids (Fig. 3A, lane 2) or compared to when the substrates were incubated separately (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 to 5). Both the CLT and the DT exhibited higher levels of incorporation when incubated together compared to the control experiments, although the degree of incorporation in the CLT was typically about three to four times greater than that in the DT when normalized to the relative mass of the plasmids in the experiment. These results indicate that a single psoralen cross-link induces DNA synthesis in the modified plasmid as well as in an undamaged homologous plasmid. That the observed synthesis is not due to an NER mechanism was shown by the induction of incorporation into the undamaged plasmid. The latter finding is the hallmark of the assay.

FIG. 3.

CRS assay with HeLa WC extract. Details of the assay are given in Materials and Methods. After incubation in the extract and processing of samples, the DNAs were codigested with (A) NcoI and BsaI or (B) NcoI and AflIII and examined by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fragments from the CLT indicated by CLT/CT contain the psoralen cross-link. The faster-migrating band in (A) is the smaller NcoI-BsaI fragment from the CLT. The upper panel represents the autoradiogram of the ethidium bromide-stained gel shown in the lower panel.

To make an initial determination of the pattern of incorporation in the CLT, the CRS assay was repeated; however, the subsequent enzyme digestions were performed with NcoI and AflIII. Use of these enzymes caused the CLT to be cleaved into two fragments, the smaller of which contained the cross-link. As shown (Fig. 3B, lane 1), even though the fragment containing the cross-link is about 1.5 times smaller than the larger of the CLT fragments, quantification of the band intensity indicated that it had approximately five times the amount of incorporation, suggesting that the observed DNA synthesis was centered around the site of the lesion. In addition, the level of incorporation observed in the larger CLT fragment was above the background level, suggesting that DNA synthesis in the CRS assay can occur over large regions of the damaged plasmid.

We next characterized the parameters of the assay in order to optimize its efficiency. To summarize these findings, we found that incubation at 22°C yielded slightly more activity (10 to 20%) than that at 30°C. The assay was strongly inhibited at 37°C. In previous work by others, it was shown that both spermidine and ammonium sulfate stimulated an in vitro recombinational assay for double-strand break repair (23). The CRS assay was not stimulated by either of these reagents. The optimum amount of salt (KCl) was determined, and the assay exhibited a broad maximum between 20 and 100 mM. With 200 mM KCl, all activity was abolished. This salt profile is similar to that observed for the NER cell-free assay (48). Both ATP and an ATP-regenerating system are required for damage-specific incorporation in the CRS assay. In the absence of ATP, only high levels of nonspecific background incorporation are observed. Kumaresan et al. (28), however, have reported site-specific incision at the site of a psoralen cross-link in the absence of ATP with mammalian cell extracts. An initial kinetic analysis of the assay indicated that incorporation was essentially linear for at least 6 h of incubation. Our typical incubation conditions for experiments reported here, unless otherwise indicated, were 3 h at 22°C in the buffer described in Materials and Methods.

Incorporation in the unmodified plasmid is dependent upon an interstrand cross-link in the CLT.

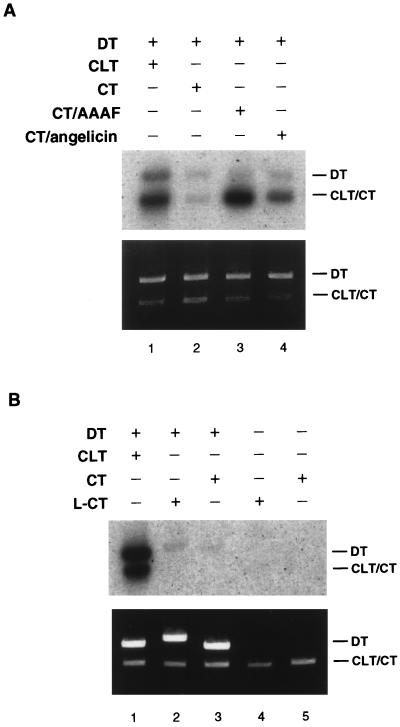

To demonstrate that the observed synthesis in the DT plasmid was dependent upon the presence of a cross-link in the CLT, we modified the CT plasmid with either AAAF or angelicin and used these substrates in place of the CLT in the CRS assay. Angelicin is a psoralen derivative that forms only monoadducts (26) and is therefore subject to repair by the NER pathway. Likewise, the AAAF-induced lesions strongly stimulate the NER pathway. As shown (Fig. 4A), neither of these adducts resulted in stimulation of incorporation into the DT above background levels. These results indicate that the presence of the interstrand cross-link is required to induce synthesis into the undamaged plasmid and therefore that the repair of this lesion occurs by a fundamentally different mechanism than that for the repair of monoadducts.

FIG. 4.

Incorporation into the donor plasmid is dependent upon the cross-link. (A) Neither AAAF or angelicin induce repair synthesis in the DT plasmid. After incubation in HeLa WC extract, the samples were processed and digested with NcoI and AvaII. (B) A double-strand break does not substitute for the interstrand cross-link. The CT plasmid was digested with SmaI to create a single blunt-ended double-strand break (L-CT). After incubation in the extract samples in lanes 1, 3, and 5 were digested with NcoI and AvaII. Samples in lanes 2 and 4 were digested with NcoI.

We also determined whether a double-strand break introduced into the CT plasmid near to the same site as the cross-link in the CLT would induce DNA synthesis. No incorporation was observed in either the CT or DT plasmids in the presence of this lesion (Fig. 4B, lane 2). Thus, a double-strand break does not mimic the pattern of incorporation observed in the presence of an interstrand cross-link. Interestingly, linearization of the DT or CLT plasmids prior to the assay does not alter the pattern of incorporation observed with the covalently closed substrates (results not shown).

Heterologous DNAs can substitute for the homologous DT plasmid.

To determine if the unmodified donor plasmid had to be completely or highly homologous to the CLT, we substituted other DNAs for the DT plasmid. A surprising pattern emerged from these experiments. The pET28 plasmid (5,369 bp), which contains regions (f1 and ColE1 origins) of exact homology to the CLT, exhibited only a modest increase in stimulation of synthesis, while the pACYC184 plasmid (4,244 bp), which contains only a small region (120 bp) of partial homology (about 70%), stimulates incorporation as efficiently as does the DT plasmid (Fig. 5). We also tested whether øx174 and simian virus 40 (SV-40) DNAs could function as donors and found that they stimulated incorporation to an intermediate level between those of pET and pACYC184 (results not shown). Neither of these DNAs has any extensive homology with the CLT. These results indicate that extensive regions of homology are not required between the damaged plasmid and the donor DNA; however, not all DNAs are equivalent as donors. The requirements for an efficient donor DNA are not apparent from these experiments.

FIG. 5.

Heterologous DNAs stimulate repair synthesis to variable extents. (A) After incubation in HeLa WC extract, the samples were digested as follows: lanes 1 and 4, NcoI and BsaI; lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6, BamHI. Digestion with BamHI caused linearization of all DNAs. (B) Histogram showing quantification of results shown in panel A. Each bar represents the sum of the band intensities of the CLT plus the DT/pET28/pACYC184 minus the sum of the band intensities of the CT plus DT/pET28/pACYC184 representing the background. The absolute incorporation was then normalized by setting the value for the DT/CLT at 100%.

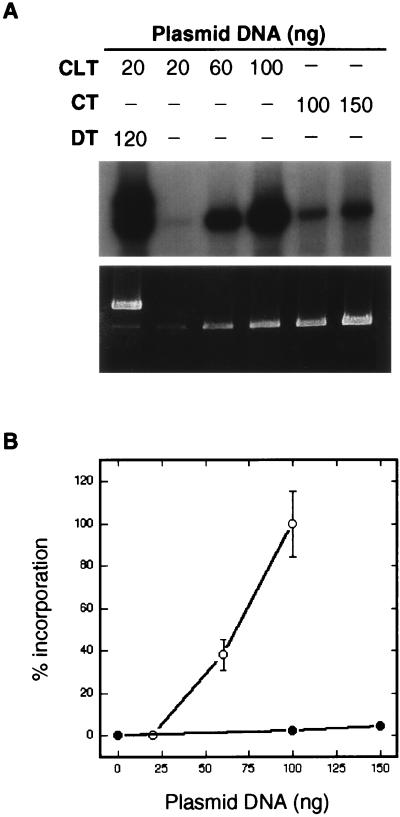

If these various DNAs can act as donors, the question arises as to why the CLT does not appear to act as its own donor. To investigate this question further, we incubated increasing amounts of the CLT in the absence of any other plasmid in the CRS assay. Interestingly, a second-order increase was observed in incorporation in the CLT (Fig. 6). Thus, the CLT may be able to act as its own donor. The second-order nature of the reaction may indicate an intermolecular reaction, or also possibly that inhibitory DNA binding proteins are being titrated out.

FIG. 6.

Incorporation into the CLT as a function of plasmid concentration. (A) After incubation in HeLa WC extract, DNAs were digested with NcoI and BsaI. (B) Quantification and graphical display of the results shown in panel A. ●, CT; ○, CLT. All values were normalized by setting the band intensity of the CLT at 100 ng to 100%.

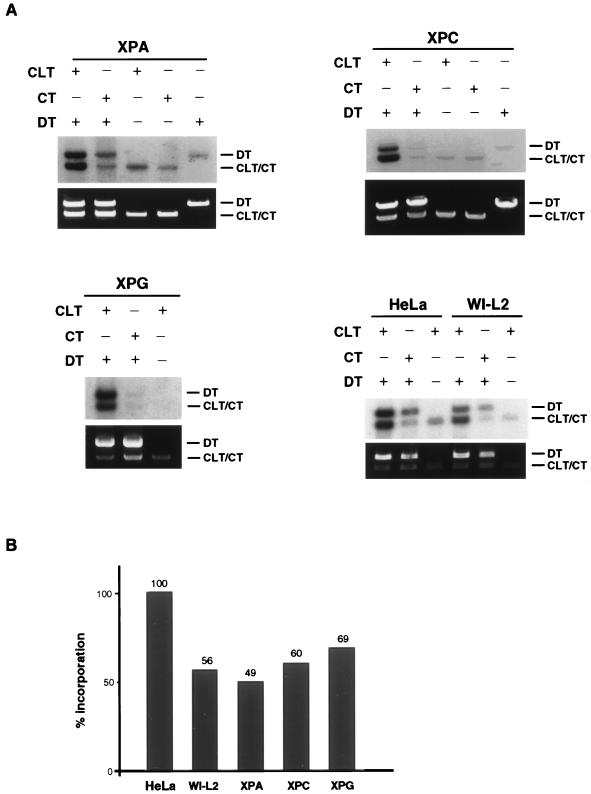

The CRS assay is not deficient in extracts from XP groups A, C, and G.

XP cell lines are highly deficient in NER as determined by both in vivo and in vitro assays (18). To determine whether or not extracts prepared from XP cell lines are also deficient in the CRS assay, we examined extracts from three XP groups. In yeast, mutations in genes (RAD14, RAD4, and RAD2) that are homologous to these XP genes have not been found to be required for recombinational repair of double-strand breaks (20), but they have been implicated in the repair of interstrand cross-links (21, 38). In the mammalian ERCC series, however, only mutant cell lines with defects in the ERCC1 or XPF-ERCC4 genes exhibit extreme hypersensitivity to cross-linking agents, while ERCC groups 2, 3, 5, and 6 exhibit only a modest sensitivity that is reasonably explained by the induction of monoadducts (1, 19). ERCC groups 2, 3, 5, and 6 are equivalent to XP groups D, B, G, and Cockayne’s syndrome group B, respectively. Shown in Fig. 7 are the results of the CRS assay performed with WC extracts prepared from cells from XP groups A, C, and G. Since these extracts were prepared from lymphoid cell lines, results with a normal human lymphoid extract (WI-L2) are also shown as a control. Typically, HeLa extracts exhibit an approximately twofold higher level of activity in the CRS assay than do extracts from lymphoid cells. All three of the XP extracts exhibited levels of activity in the CRS assay quantitatively similar to the normal lymphoid control, indicating that these extracts were competent for cross-link-induced DNA synthesis. These results are consistent with the cellular findings and indicate that these XP proteins do not play a major role in the repair of interstrand cross-links as determined by the CRS assay. These findings also strengthen our conclusion that the CRS assay is distinct from the cell-free assay for NER.

FIG. 7.

CRS assay with XP cell lines. The CRS assay was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (A) Results of the CRS assay for extracts from XP cells representing groups A (GM02345C), C (GM02246B), and G (XPG83). (B) Histogram showing quantification of the results shown in panel A. Each bar represents the sum of the band intensities of the CLT plus the DT minus the sum of the band intensities of the CT plus DT. The absolute incorporation was then normalized by setting the value for HeLa cells at 100%.

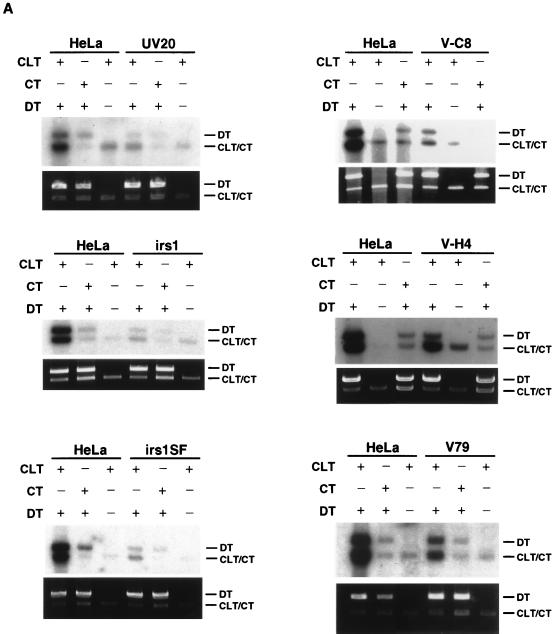

The CRS assay in rodent mutants hypersensitive to cross-linking agents.

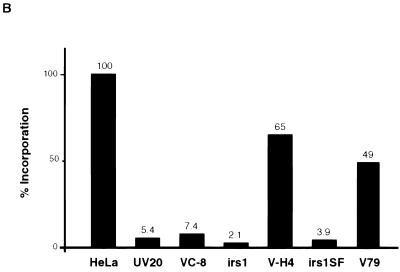

A number of rodent mutants (Table 1) that are highly sensitive to the cross-linking agent mitomycin C have been identified (13). We have evaluated extracts prepared from several of these mutant cell lines for activity in the CRS assay. As was found for human lymphoid cell lines, extracts from a wild-type hamster cell line (V79) generally exhibited 1.5- to 2-fold lower activity than did HeLa cell extracts (Fig. 8). Extracts from UV20, V-C8, irs1, and irs1SF mutant cell lines were all highly deficient in the CRS assay. Extracts from UV41 cells representing complementation group 4 were also highly negative in the assay (see below). Extracts from the cell line V-H4 exhibited a wild-type level of activity. The finding that irs1 and irs1SF mutant cells are deficient in the assay is of particular interest since the genes that complement these cells, XRCC2 and XRCC3, have recently been cloned and both are members of the RecA gene family (32).

TABLE 1.

Rodent mutants hypersensitive to cross-linking agentsa

| Mutant | MMC sensitivityb | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| UV20 | 90× | ERCC1 |

| UV41 | 90× | XPF-ERCC4 |

| irs1 | 60× | XRCC2 |

| irs1SF | 100× | XRCC3 |

| V-C8 | 110× | ? |

| V-H4 | 33× | FAA? |

Adapted from Collins (13).

Compared to the value (1×) in the parental strain. MMC, mitomycin C.

FIG. 8.

CRS assay with rodent mutants hypersensitive to cross-linking agents. (A) The CRS assay was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (A) Results of the CRS assay for extracts from rodent cell lines UV20, V-C8, irs1, irs1SF, V-H4, and V79. (B) Histogram showing quantification of the results shown in panel A. Bar values were arrived at as described in the legend to Fig. 7.

The V-H4, V-C8, irs1, and irs1SF cell lines have no known defect in NER. To ensure that extracts from each cell line were prepared properly, each extract was analyzed in the NER cell-free assay and was found competent by this measure (results not shown). UV20 mutants are, however, defective in NER due to a mutation in ERCC1. Thus, to demonstrate the quality of the extracts prepared from this cell line, we performed a complementation assay by addition of purified ERCC1-XPF protein complex. Complementation was observed in the NER assay, indicating that the UV20 extracts were properly prepared (results not shown).

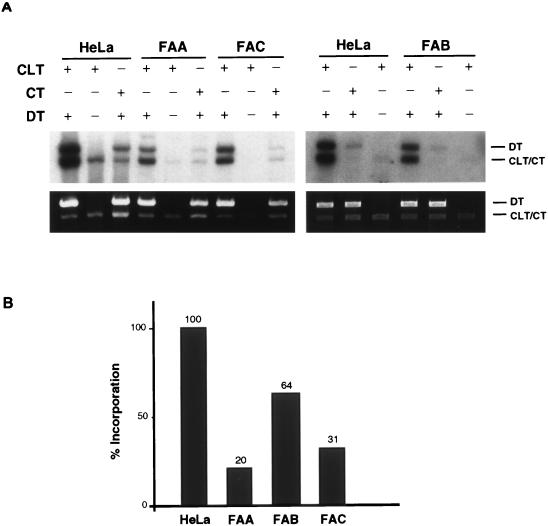

The CRS assay in FA cell lines.

FA is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by congenital abnormalities, progressive bone marrow failure, and a marked predisposition to leukemia (6). Cells from FA patients exhibit a hypersensitivity to DNA bifunctional cross-linking agents, such as diepoxybutane and mitomycin C, but not to monofunctional agents (2). FA is genetically heterogeneous in that at least eight complementation groups (A to H) have been identified (24, 25, 41). We assayed extracts from lymphoid cell lines representing three of these groups, A, B, and C, in the CRS assay (Fig. 9). Extracts from groups A and C exhibited approximately half the activity found in a normal lymphoid cell line, while an extract from group B cells showed normal levels of activity. These results indicate that, in general, extracts from FA cells are not highly defective in the CRS assay, as was found for the rodent mutants, but may have a partial reduction in the stimulation of DNA synthesis in response to an interstrand cross-link.

FIG. 9.

CRS assay with FA cell lines. The CRS assay was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (A) Results of the CRS assay for extracts from FA cells representing groups A (GM13022), B (GM13071), and C (GM13020). (B) Histogram showing quantification of the results shown in panel A. Bar values were arrived at as described in the legend to Fig. 7.

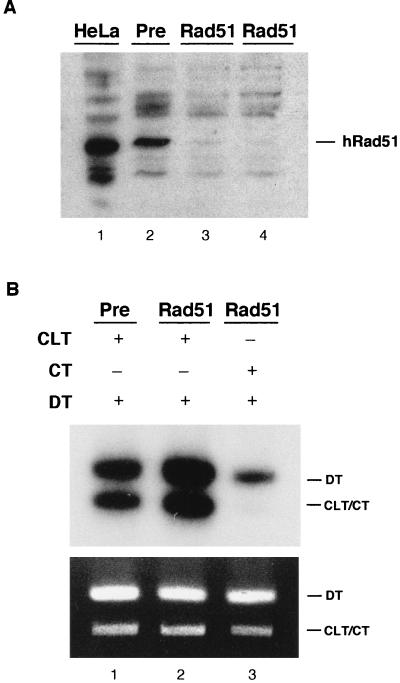

hRad51 is not required for the CRS assay.

Rad51 is a eucaryotic homologue of the E. coli homologous recombination protein RecA, and both the human and yeast proteins have been shown to mediate strand transfer reactions in vitro (3, 43). Experiments described above (Fig. 5) indicated that nonhomologous plasmids could act as donors in the CRS assay and therefore suggested that Rad51 may not be required for cross-link repair in vitro. To determine if hRad51 is required in cross-link repair, HeLa extracts were immunodepleted of the protein, and subsequently examined in the CRS assay. As shown (Fig. 10A), greater than 95% removal of hRad51 was obtained by immunodepletion with antiserum as compared to preimmune serum. Examination of the hRad51-depleted extracts in the CRS assay showed no loss of activity compared to extracts depleted with preimmune serum (Fig. 10B). In fact, a moderate and reproducible increase in activity was observed in the hRad51-depleted extracts.

FIG. 10.

CRS assay with hRad51-depleted extracts. (A) Western analysis of HeLa cell extracts immunodepleted with a polyclonal rabbit serum raised against hRad51. Lane 1, untreated HeLa cell extract; lane 2, extract treated with preimmune serum; lanes 3 and 4, extracts treated with hRad51 antiserum. (B) CRS assay of treated extracts. Lane 1, extract treated with preimmune serum; lanes 2 and 3, extract treated with hRad51 antiserum.

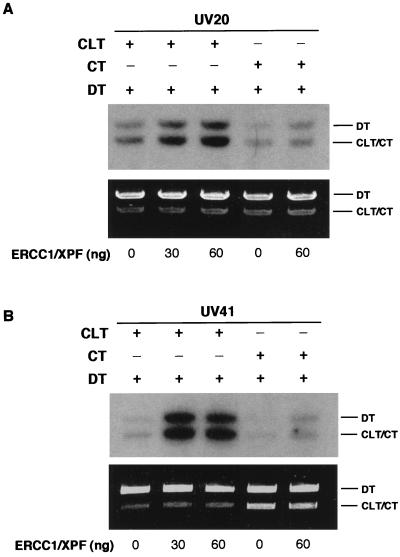

Complementation of defective extracts in the CRS assay.

Complementation of defective extracts is an established biochemical method for verifying the validity of an assay. As described above, extracts prepared from UV20 and UV41 cells are highly deficient in the CRS assay. These two mutant cell lines are defective in ERCC1 and XPF function, respectively. We obtained purified samples of the ERCC1-XPF complex and determined whether this complex could complement either of these extracts. For both cell lines, robust complementation was observed with the addition of the ERCC1-XPF complex (Fig. 11A and B). These results demonstrate that extracts deficient in the CRS assay can be rescued specifically by purified proteins, although complementation of the XRCC2- XRCC3- and V-C8-deficient extracts must also be obtained in order to confirm the role of these proteins in the CRS assay.

FIG. 11.

Complementation of UV20 and UV41 mutant extracts with purified ERCC1-XPF protein.

DISCUSSION

Great progress has been made in recent years on the elucidation in eucaryotic cells of the multiple mechanisms of repair of double-strand breaks (22). However, little is known about the mechanisms of repair of interstrand cross-links in these systems. In both yeast and mammals it is clear that genes that are involved in recombinational processes are also components of cross-link repair (44). Here, we describe the development of a mammalian cell-free assay which is based upon the measurement of DNA synthesis induced by the presence of a single psoralen interstrand cross-link. Under the conditions employed, the damage-induced DNA synthesis is dependent upon the presence of the cross-link and is stimulated by the presence of an undamaged donor plasmid. Some degree of this stimulation may be due to titration of inhibitory factors; however, the most intriguing finding is that the damage-induced DNA synthesis is observed in both the plasmid containing the cross-link and the undamaged plasmid. The latter finding is the hallmark of the assay since it has not been observed previously in the repair of UV-induced photoproducts, psoralen monoadducts, or other lesions susceptible to repair by the NER pathway (39, 48). We also showed that psoralen monoadducts, AAAF-induced lesions, and double-strand breaks do not induce DNA synthesis in an undamaged plasmid. The stimulation of incorporation by an undamaged plasmid and the finding of DNA synthesis in this plasmid suggest that a recombinational mode of DNA repair is occurring. Importantly, we also found that the undamaged plasmid does not have to be homologous to the damaged plasmid in order to stimulate DNA synthesis, although why some DNAs stimulate synthesis to a greater degree than others is not clear since it does appear to be based on overall homology. Nevertheless, this observation seems to suggest that Cole’s model involving homologous recombination is not the operative pathway for repair of cross-links in the CRS assay. This conclusion is further supported by our finding that hRad51 is not required for the CRS assay.

That the observed incorporation is unlikely to be due to damage-induced aberrant DNA synthesis is indicated by the following reasons. (i) The incorporation into the undamaged DNA is cross-link specific and is not observed in the presence of monoadducts or double-strand breaks. (ii) Mutant cell lines that are sensitive to cross-linking reagents in vivo are for the most part deficient in the CRS assay. (iii) Incorporation of nucleotides into the undamaged plasmid suggests that we are observing a type of damage processing that involves some form of recombination. This finding is not observed in the in vitro assay for repair of photoproducts by NER (39, 48).

In E. coli, it is clear that the uvr pathway plays an essential role in the repair of interstrand cross-links (11, 12). In yeast as well, components of the incision stage of the NER pathway have been implicated in the repair of interstrand cross-links (21, 38). However, the role of mammalian NER genes in the repair of interstrand cross-links has proven to be controversial. One reason for this situation is that many, if not most, interstrand cross-linking agents also produce monoadducts which are typically repaired by the NER pathway. Thus, it is often difficult to determine whether the sensitivity of mutants is due to the monoadduct or to the interstrand cross-link. The study by Hoy et al. (19) found, however, that of the first five ERCC complementation groups, only groups 1 and 4 were extremely hypersensitive to cross-linking agents. A more recent study by Andersson et al. (1) have noted similar results using cyclophosamide analogs as the cross-linking agent. They showed that groups 1 and 4 were approximately 30-fold more sensitive to these drugs than groups 2, 3, 5, and 6. The CRS assay allows for a biochemical determination of the role of NER proteins in interstrand cross-link repair. As we showed above, XP groups A, C, and G were all proficient in DNA synthesis, indicating that these NER proteins are not involved in cross-link repair as measured by the CRS assay. Moreover, consistent with the previously reported in vivo studies, we have found that extracts from the rodent mutants mutated in ERCC1 or XPF-ERCC4 are highly defective in the CRS assay. However, it must be noted that NER proteins could play a role in the second incision step (Fig. 1) which might occur after the bulk of the DNA synthesis has taken place as measured in the CRS assay. Somewhat in contrast with our results, Bessho et al. (4) have recently reported that reconstituted NER incision proteins can perform dual incisions near the site of cross-links. Curiously, however, the incisions do not flank the cross-link as proposed in E. coli (11, 12), but are found slightly 5′ to the cross-linked base. It is therefore possible that NER proteins are involved in a second, but most likely minor, pathway of cross-link repair.

As described above (Table 1), a number of rodent cell lines, in addition to the ERCC group 1 and 4 mutants, that are hypersensitive to cross-linking agents have been identified (13). We have analyzed extracts from a number of these cell lines and found, consistent with their in vivo phenotype, that they are highly defective in the CRS assay. The only exception was the cell line V-H4. V-H4 and FA-A may represent the same molecular defect since there is evidence from cell fusion studies to indicate that FA-A and V-H4 cell lines belong to the same complementation group (52). It is also possible that the V-H4 gene product participates in a step of the repair reaction subsequent to DNA synthesis. The human genes that complement UV20 (47) and the irs1 and irs1SF mutants (32) have been isolated, but the cloning of the gene for V-C8 has not been reported. The finding that these mutants are deficient in the CRS assay is consistent with the in vivo results showing extreme hypersensitivity of these mutants to cross-linking reagents (13). This overall correlation between our in vitro results and the previous cellular findings strongly validates the CRS assay as a measure of cross-link repair. In addition, the finding that extracts deficient in XRCC2 and XRCC3, both of which are related to the RecA-hRad51 family (32), suggests that the CRS assay may be reflective of recombinational repair processes. Furthermore, it should be noted that the CRS assay does not distinguish as to whether the defects in these hamster cells is reflective of a deficiency in an incision step or a synthesis step of cross-link repair.

In contrast to their in vivo hypersensitivity to interstrand cross-linking agents, FA complementation groups A, B and C showed significant activity in the CRS assay, although groups A and C exhibited approximately half the activity observed in extracts from control lymphoid cells. Both the FAA (14, 33) and FAC (42) genes have been cloned, and both polypeptides predicted from their sequences represent novel proteins of unknown function. It has been reported that the FAC protein is localized entirely in the cytoplasm (49, 51) and further that the cytoplasmic location of FAC is essential for its function since when it is targeted to the nucleus it fails to correct the defect in FAC cells (50). These results and others suggest that FA proteins may be involved in a cytoplasmic defense mechanism, such as prevention of oxidative damage, rather than having a direct role in DNA repair processing. However, more recent findings indicate an interaction between FAA and FAC that results in translocation of the complex into the nucleus (29). Consistent with these results is a recent model that proposes that FA proteins are involved in a pathway of feedback control of DNA replication during S phase of the cell cycle (16). Other studies have suggested that FA proteins may be involved in regulating apoptosis and/or the cell cycle after exposure to cross-linking agents (5). Our in vitro results are somewhat ambiguous in regard to a direct role for FA proteins in DNA repair in that FA groups A and C are subnormal but not highly deficient as was found for the crosslink-sensitive rodent mutants, while group B cells exhibited a wild-type level of activity.

There is substantial evidence to indicate that Cole’s model (Fig. 1) is the likely mechanism for repair of interstrand cross-links in E. coli (12). However, the applicability of this pathway in mammalian cells is questionable since we have shown that elements of the NER machinery other than ERCC1-XPF are not required for steps preceding DNA synthesis and that there is no absolute requirement for extensive homology between damaged and undamaged plasmids in the CRS assay. There are four identified pathways of double-strand break repair that have been identified in eukaryotic cells. These are (i) homologous recombination (HR), (ii) nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), (iii) single-strand annealing (SSA), and (iv) break-induced replication (BIR). It is a distinct possibility that a modification of one of these pathways represents the mechanism of interstrand cross-link repair that is observed in the CRS assay. Both NHEJ and SSA can be eliminated as candidates on the basis that there is no obvious requirement for a donor plasmid in these mechanisms. Both HR and BIR require short segments of homology to initiate the strand transfer reaction; however, HR also requires extensive homology for branch migration of the Holliday junction, whereas, BIR requires no further homology because the resulting D loop is extended by DNA synthesis (35). Thus, the BIR mechanism is consistent with our finding that extensive homology between the damaged and donor plasmids is not required. HR and BIR have also been distinguished in yeast by their genetic requirements. HR is RAD51 dependent but RAD1 independent, while BIR has been shown to be RAD51 independent and RAD1 dependent (7, 35). We have shown here that the CRS assay is dependent upon the mammalian homologue of Rad1, XPF, and also the protein with which it is complexed, ERCC1. In addition, we demonstrated that immunodepletion of hRad51 from HeLa extracts did not reduce activity in the CRS assay, indicating that it is Rad51 independent. It should be noted, however, that the lack of involvement of Rad51 in the CRS assay does not necessarily indicate that it is not involved in cross-link repair. It may be involved in a step subsequent to the DNA synthesis. Nevertheless, the BIR model, presumably in some modified form, is most consistent with the results that we have obtained from the CRS assay. Finally, it is also clear that cross-links are not simply processed into double-strand breaks and subsequently repaired as such, since our in vitro results show that cross-links elicit extensive DNA synthesis while double-strand breaks do not.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Sancar and Z.-Q. Pan for providing purified proteins and M. Zdzienicka and N. Jones for providing cell lines.

This work was supported by American Federation of Aging Research grant A95035 and National Institutes of Health grants CA52461, CA75160 and CA76172.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson B S, Sadeghi T, Sicilano M J, Legerski R J, Murray D. Nucleotide excision repair genes as determinants of cellular sensitivity to cyclophosphamide analogs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996;38:406–416. doi: 10.1007/s002800050504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach A D. Fanconi anaemia diagnosis and the diepoxybutane (DEB) test. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:731–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann P, Benson F E, West S C. Human Rad51 protein promotes ATP-dependent homologous pairing and strand transfer reactions in vitro. Cell. 1996;87:757–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessho T, Mu D, Sancar A. Initiation of DNA interstrand cross-link repair in humans: the nucleotide excision repair system makes dual incisions 5′ to the cross-linked base and removes a 22- to 28-nucleotide-long damage-free strand. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald M, Moustacchi E. Is Fanconi anaemia caused by a defect in the processing of DNA damage? Mutat Res. 1998;408:75–90. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(98)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butturini A, Gale R P, Verlander P C, Adler-Brecher B, Gillio A P, Auerbach A D. Hematologic abnormalities in Fanconi anaemia: an international Fanconi anaemia registry study. Blood. 1994;84:1650–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Umezu K, Kolodner R D. Chromosomal rearrangements occur in S. cerevisiae rfa1 mutator mutants due to mutagenic lesions processed by double-strand-break repair. Mol Cell. 1998;2:9–22. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng S, Sancar A, Hearst J E. RecA-dependent incision of psoralen-crosslinked DNA by (A)BC exinuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:657–663. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng S, Van Houten B, Gamper H B, Sancar A, Hearst J E. Use of psoralen-modified oligonucleotides to trap three-stranded RecA-DNA complexes and repair of these cross-linked complexes by ABC exinuclease. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15110–15117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimino G D, Gamper H B, Isaacs S T, Hearst J E. Psoralens as photoactive probes of nucleic acid structure and function: organic chemistry, photochemistry, and biochemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:1151–1193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole R S. Repair of DNA containing interstrand crosslinks in Escherichia coli: sequential excision and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:1064–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole R, Levitan S D, Sinden R R. Removal of psoralen interstrand crosslinks from DNA of Escherichia coli: mechanism and genetic control. J Mol Biol. 1976;103:39–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins A R. Mutant rodent cell lines sensitive to ultraviolet light, ionizing radiation and cross-linking agents: a comprehensive survey of genetic and biochemical characteristics. Mutat Res. 1993;293:99–118. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(93)90062-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:579–585. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Digweed M, Sperling K. Molecular analysis of Fanconi anaemia. BioEssays. 1996;18:579–585. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanconi Anaemia/Breast Cancer Consortium. Positional cloning of the Fanconi anaemia group A gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:324–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankenburg D M, Frankenburg-Schwager M, Blocher D, Harbich R. Evidence for DNA double-strand breaks as the critical lesions in yeast cells irradiated with sparsely or densely ionizing radiation under oxic and anoxic conditions. Radiat Res. 1981;88:524–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoy C A, Thompson L H, Mooney C L, Salazar E P. Defective DNA cross-link removal in Chinese hamster cell mutants hypersensitive to bifunctional alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1737–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanov E L, Haber J E. RAD1 and RAD10, but not other excision repair genes, are required for double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2245–2251. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jachymczyk W J, Von Borstel R C, Mowat M R A, Hastings P J. Repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires two systems of DNA repair: the RAD3 system and the RAD51 system. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:196–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00269658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeggo P A. DNA-PK: at the cross-roads of biochemistry and genetics. Mutat Res. 1997;384:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jessberger R, Podust V, Hubscher U, Berg P. A mammalian complex that repairs double-strand breaks and deletions by recombination. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15070–15079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joenje H, Lo Ten Foe F J R, Oostra A B, van Berkel C G, Rooimans M A, Schroeder-Kurth T, Wegner R D, Gille J J, Buchwald M, Arwert F. Classification of Fanconi anaemia patients by complementation analysis: evidence for a fifth genetic subtype. Blood. 1995;86:2156–2160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joenje H, Oostra A B, Wijker M, di Summa F M, van Berkel C G M, Rooimans M A, Ebell W, van Weel M, Pronk J C, Buchwald M, Arwert F. Evidence for at least eight Fanconi anaemia genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:940–944. doi: 10.1086/514881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kittler L, Hradecna Z, Suhnel J. Cross-link formation of phage lambda DNA in situ photochemically induced by the furocoumarin derivative angelicin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;607:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(80)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohn K W. Beyond DNA cross-linking: history and prospects of DNA-targeted cancer treatment—Fifteenth Bruce F. Cain Memorial Award Lecture. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5533–5546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumaresan K R, Hang B, Lambert M W. Human endonucleolytic incision of DNA 3′ and 5′ to a site-directed psoralen monoadduct and interstrand cross-link. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30709–30716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupfer G M, Naf D, Suliman A, Pulsipher M, D’Andrea A D. The Fanconi anaemia proteins, FAA and FAC, interact to form a nuclear complex. Nat Genet. 1997;17:487–490. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legerski R J, Gray H B, Jr, Robberson D L. A sensitive endonuclease probe for lesions in deoxyribonucleic acid helix structure produced by carcinogenic or mutagenic agents. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:8740–8746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J J, Kely T J. Simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6973–6977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu N, Lamerdin J E, Tebbs R S, Schild D, Tucker J D, Shen M R, Brookman K W, Siciliano M J, Walter C A, Fan W, Narayana L S, Zhou Z Q, Adamson A W, Sorensen K J, Chen D J, Jones N J, Thompson L H. XRCC2 and XRCC3, new human Rad51-family members, promote chromosome stability and protect against DNA crosslinks and other damages. Mol Cell. 1998;1:783–793. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo Ten Foe J R, Rooimans M A, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Alon N, Wijker M, Parker L, Lightfoot J, Carreau M, Callen D F, Savoia A, Cheng N C, van Berkel C G M, Strunk H P, Gille H J P, Pals G, Kruyt F A E, Pronk J C, Arwert F, Buchwald M, Joenje H. Expression cloning of a cDNA for the major Fanconi anaemia gene, FAA. Nat Genet. 1996;14:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magana-Schwencke N, Henriques J A, Chanet R, Moustacchi E. The fate of 8-methozypsoralen photoinduced crosslinks in nuclear and mitochondrial yeast DNA: comparison of wild-type and repair-deficient strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1722–1726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malkova A, Ivanov E L, Haber J E. Double-strand break repair in the absence of RAD51 in yeast: a possible role for break-induced replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7131–7136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manley J L, Fire A, Cano A, Sharp P A, Gefter M L. DNA-dependent transcription of adenovirus genes in a soluble whole-cell extract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3855–3859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBlane J F, van Gent D C, Ramsden D A, Romeo C, Cuomo C A, Gellert M, Oettinger M A. Cleavage at a V(D)J recombination signal requires only RAG1 and RAG2 proteins and occurs in two steps. Cell. 1995;83:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller R D, Prakash L, Prakash S. Genetical control of excision of Saccharoymyces cerevisiae interstrand DNA cross-links induced by psoralen plus near-UV light. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:939–948. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.8.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sibghat-Ullah S, Husain I, Carlton W, Sancar A. Human nucleotide excision repair in vitro: repair of pyridine dimers, psoralen and cisplatin adducts by HeLa cell-free extract. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4471–4484. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sladek F M, Munn M M, Rupp W D, Howard-Flanders P. In vitro repair of psoralen-DNA cross-links by RecA, UvrABC, and the 5′-exonuclease of DNA polymerase I. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6755–6765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strathdee C A, Duncan A M V, Buchwald M. Evidence for at least four Fanconi anaemia genes including FACC on chromosome 9. Nat Genet. 1992;1:196–198. doi: 10.1038/ng0692-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strathdee C A, Gavish H, Shannon W R, Buchwald M. Cloning of cDNAs for Fanconi’s anaemia by functional complementation. Nature. 1992;356:763–767. doi: 10.1038/356763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sung P, Robberson D L. DNA strand exchange mediated by a RAD51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament with polarity opposite to that of RecA. Cell. 1995;82:453–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson L H. Evidence that mammalian cells possess homologous recombinational repair pathways. Mutat Res. 1996;363:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Houten B, Gamper H, Holbrook S R, Hearst J E, Sancar A. Action mechanism of ABC excision nuclease on a DNA substrate containing a psoralen crosslink at a defined position. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8077–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warmer W G, Timmer W C, Wei R R, Miller S A, Kornhauser A. Furocoumarin-photosensitized hydroxylation of guanosine in RNA and DNA. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;61:336–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb08618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westerveld A, Hoeijmakers J H, van Duin M, de Wit J, Odijk H, Pastink A, Wood R D, Bootsma D. Molecular cloning of a human DNA repair gene. Nature. 1984;310:425–429. doi: 10.1038/310425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wood R D, Robins P, Lindahl T. Complementation of the xeroderma pigmentosum DNA repair defect in cell-free extracts. Cell. 1988;53:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamashita T, Barber D L, Zhu Y, Wu N, D’Andrea A D. The Fanconi anaemia polypeptide FACC is localized to the cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6712–6716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youssoufian H. Localization of Fanconi anaemia C protein to the cytoplasm of mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7975–7979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Youssoufian H. Cytoplasmic location of FAC is essential for the correction of a prerepair defect in Fanconi anaemia group C cells. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:2003–2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI118635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zdzienicka M Z, Arwert F, Neuteboom I, Rooimans M, Simons J W. The Chinese hamster V79 cell mutant V-H4 is phenotypically like Fanconi anaemia cells. Cell Mol Genet. 1990;16:575–581. doi: 10.1007/BF01233098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]