Dear Editors,

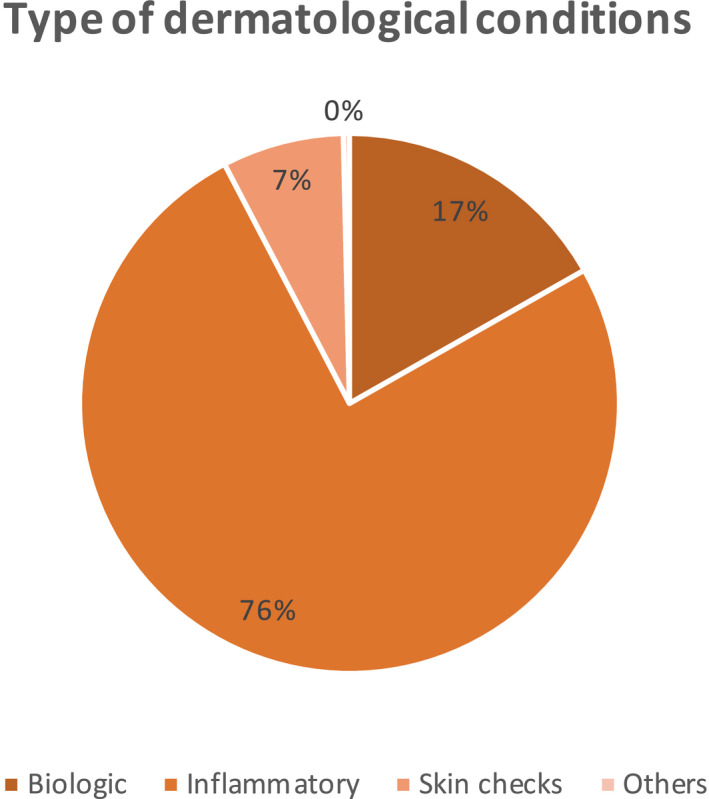

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID‐19 outbreak a pandemic [1]. Victoria declared a ‘state of emergency’, restrictions including a lockdown were put in place. These lasted for 2.5 months [2]. This study analyses the dermatology telehealth experience at the Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) during this period and compares it to the experience of dermatologists Australia wide. RMH runs 5 medical and 2 surgical dermatology sessions a week, serving on average 133 patients. During the pandemic teledermatology became the normal, surgical dermatology was reduced to 1 session of category 1 and 2 cases. During this 2.5‐month period, 554 telehealth encounters and 433 face‐to‐face consultations were conducted. The largest group of cases were inflammatory conditions (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Type of dermatological conditions during RMH 2.5‐month teledermatology period.

We carried out a local audit after each clinic to assess clinicians’ impression on telehealth consultations for one month. There were 267 telehealth consultations and 124 face‐to‐face consultations. Most clinicians found that telehealth consultations were inadequate or inferior to face‐to‐face consultations. Only 27% of the telehealth encounters were found to be equal to face‐to‐face consultations.

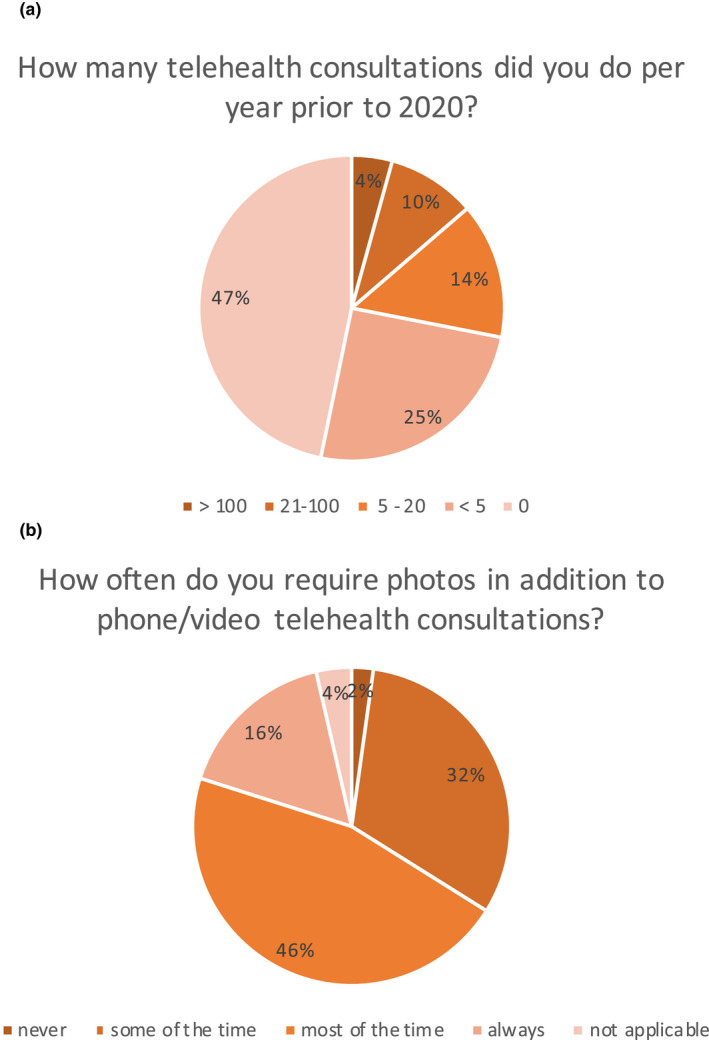

To put this local experience into broader context, we evaluated the telehealth experience of Australian dermatologists via a 22‐question online survey on June 29, 2020 [RMH HREC QA 2020060]. 137 of 559 dermatologists completed the survey, 50% women and 87.1% working in metropolitan area. The largest group (34.5%) had been practicing for over 20 years. 53.24% reported that they had utilized telehealth consultation prior to 2020 (Fig 2). During the pandemic, 79 of the 89 dermatologists in public hospitals started using telehealth via hospital telehealth platform or telephone. 92.6% of the 136 dermatologists in private practice, started telehealth, frequently using informal software such as WhatsApp, Facetime and Skype. There are four main teledermatology care delivery methods – store‐and‐forward, video conferencing, mobile teledermatology and hybrid teledermatology [3]. Hybrid teledermatology – where photographs are used in combination with videoconferencing – was the most popular amongst dermatologists, with 92% preferring photos prior to consultation. Only 3 dermatologists (2.2%) did not require photos in addition to telehealth consultation (Fig 2). 63.8% reported that telehealth consultations were more time consuming than face‐to‐face consultations.

Figure 2.

Findings of 22‐question survey on telehealth experience by 137 Australian dermatologists. (a) Telehealth consultations prior to 2020. (b) Photos in addition to phone/video telehealth consultations.

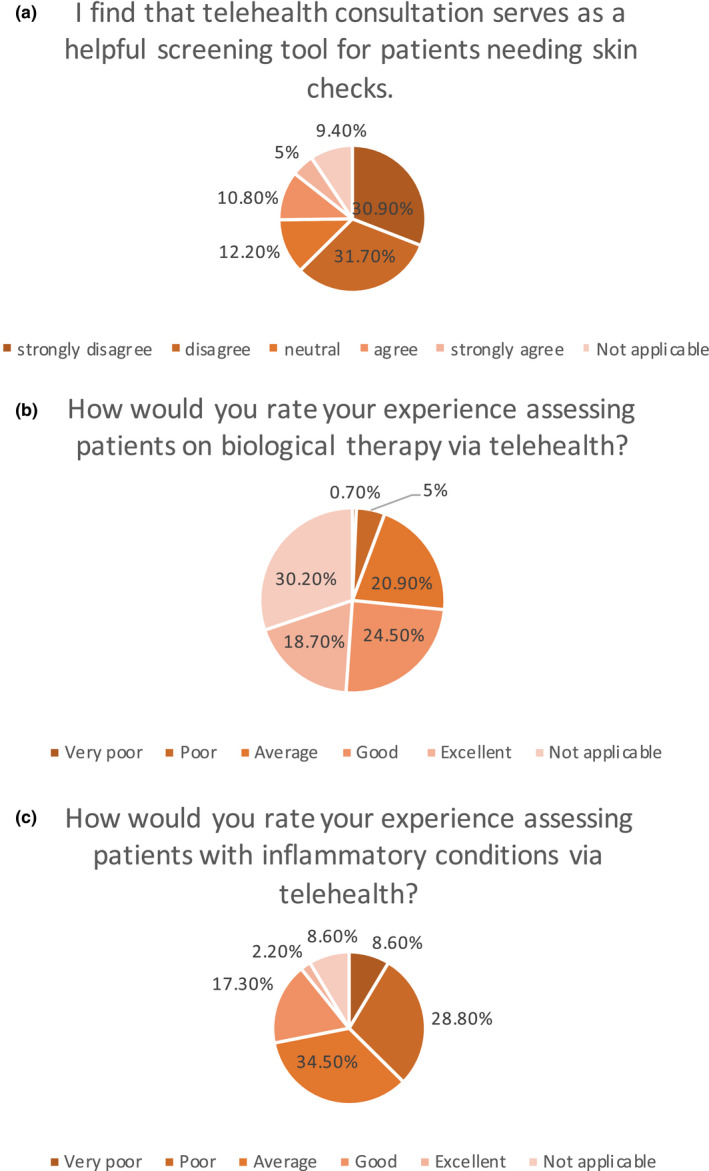

The use of teledermatology for different conditions had varying acceptance (Fig 3). Only 4 of the 139 responses found skin checks via telehealth ‘good’ or ‘average’. 78.4% found that skin checks via telehealth were inappropriate. In our audit finding, all skin check telehealth consultations were deemed inappropriate or inferior. Interestingly, 62.6% of survey respondents did not think that telehealth consultation should be used as a screening tool for skin checks. 64.3% reported that telehealth was an appropriate method in providing care for patients on biologic therapy. Our audit found that 76% of telehealth consultations for biologic patients were superior or equal to face‐to‐face consultations. For inflammatory conditions, 54% reported that telehealth was reasonable, 2.2% that it was excellent. Overall, Australian dermatologists found that their experience with telehealth was as expected [median of 50 (25‐63)] with 64.8% reporting that they would continue using telehealth after the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Figure 3.

Findings of 22‐question survey on telehealth experience by 137 Australian dermatologists. (a) Skin examination and telehealth. (b) Patients on biologic therapy and telehealth. (c) Patients with inflammatory conditions and telehealth.

Teledermatology is often perceived to be more challenging than face‐to‐face consultations [4]. Prior to COVID‐19, the evaluation of healthcare provider telehealth experience was limited. The European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) conducted an online survey early in the pandemic with 444 European dermatologists completing the survey [5]. The Indian group of Sharma et al. conducted an online survey and 184 dermatologists completed the survey [4]. Both papers showed that there was a positive change in attitude with the increased use of teledermatology during the pandemic. Our results confirm these findings. In our study, the percentage of telehealth consultations that were found to be equal to face‐to‐face consultations and the percentage reported as reasonable for inflammatory conditions were lower than published in the literature [6]. This may be in part because a substantial group of dermatologists represented here had not used teledermatology prior. Future research would be valuable to address why this was the case and how it could be best approached, for example, with appropriate training.

Conclusion

The COVID‐19 pandemic has led to most dermatologists in Australia gaining first‐hand experience in teledermatology. Moving forward, hybrid teledermatology seems to be the preferred delivery method, using practical telehealth guidelines created for the Australian context [7]. The results presented here include responses from a significant number of dermatologists who had not used telehealth before. They indicate that teledermatology may be most suited for ongoing care of patients on biologic therapy and with certain inflammatory conditions. For skin checks, specific set ups may be required.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

The Royal Melbourne Hospital HREC approval number QA2020060.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank their colleagues who participated in the national Dermatology Telehealth survey.

Funding source: None.

Conflict of interest: The Royal Melbourne Hospital Foundation received an unrestricted grant for Fellowship support for a Dermatology Rural Outreach Registrar from Janssen‐Cilag Pty Ltd. Janssen‐Cilag Pty Ltd had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript or publication decisions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghebreyesus T. WHO Director ‐ General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19 ‐ 11 March 2020 . 2020 [cited 2020 20 September 2020]; Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐media‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19‐‐‐11‐march‐2020.

- 2. Mclean HH, Ben. Emergency Powers, Public Health and COVID‐19 . 2020, Parliamentary Library & Information Service: Department of Parliamentary Services.

- 3. Armstrong AW, Kwong MW, Ledo L et al. Practice models and challenges in teledermatology: a study of collective experiences from teledermatologists. PLoS One 2011; 6: e28687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharma A, Jindal V, Singla P et al. Will Teledermatology be the silver lining during and after COVID‐19? Dermatol Ther 2020; e13643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moscarella E, Pasquali P, Cinotti E et al. A survey on teledermatology use and doctors' perception in times of COVID‐19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: e772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winters JM. A telehomecare model for optimizing rehabilitation outcomes. Telemed J E Health 2004; 10: 200–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abbott LM, Miller R, Janda M et al. Practice guidelines for teledermatology in Australia. Australas J Dermatol 2020; 61: e293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]