Background

Since the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, our colleagues working at eight different Tourette syndrome (TS) clinics globally have witnessed a parallel pandemic of young people aged 12 to 25 years (almost exclusively girls and women) presenting with the rapid onset of complex motor and vocal tic‐like behaviors. 1 In most cases, these behavioral patterns are consistent with a functional neurological disorder. There have been striking commonalities in the phenomenology of these tic‐like behaviors observed across our centers in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Australia. The aim of this viewpoint is to help clinicians recognize patients with this disorder and distinguish them from patients with TS. We begin by describing the clinical phenomenology and demographic characteristics of youth with rapid onset functional tic‐like behaviors (FTLBs) using illustrative data from the Tic Disorders Clinical Registry at the Calgary Tourette and Pediatric Movement Disorders Clinic. We then discuss our shared experiences across our eight centers and provide preliminary viewpoints on the pathophysiology and treatment of this complex disorder.

The Calgary Tic Disorders Clinical Registry

This registry enrolls participants at their first clinic visit into a prospective cohort study assessing long‐term outcomes in youth with tics. The registry is approved by the Calgary Health Research Ethics Board, and all participants provide informed consent. Baseline data elements include age, sex, age at tic onset, current medication use, tic disorder diagnosis, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score, presence of comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and symptom severity on the Conners 3, obsessive‐compulsive disorder and symptom severity on the Children's Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CYBOCS), anxiety disorder (including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, or panic disorder) and symptom severity on the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children version 2 (MASC2), major depressive disorder and symptom severity on the Child Depression Inventory version 2 (CDI2), and autism. Possible tic disorder diagnoses recorded in the registry included TS, persistent motor tic disorder (PMTD), persistent vocal tic disorder (PVTD), and provisional tic disorder (PTD). The diagnosis of FTLBs was added to the registry in 2020. Using this registry data, we contrasted clinical features present at the first clinical visit of participants diagnosed with primary tic disorders and those diagnosed with FTLBs. Children categorized with primary tic disorders met DSM‐V criteria for TS, PMTD, PVTD, or PTD. Children categorized with FTLBs had rapid onset of complex tic‐like behaviors, with escalation to peak severity within hours to days. All diagnoses were performed by movement disorders specialists with expertise in tic disorders. Continuous variables were compared between groups using a 2‐sample t test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test.

Data from 290 registry participants collected between 2012 and June 30, 2021, were analyzed, comprising 270 with a primary tic disorder (215 TS, 28 PMTD, 4 PVTD, and 23 PTD) and 20 with FTLBs. Of the 20 patients with FTLBs, 17 had no history of previous tics, whereas 3 had mild simple tics earlier in childhood that were never detected. Rapid onset of FTLBs occurred in all participants during the pandemic period (after March 1, 2020), and all endorsed exposure to influencers on social media (mainly TikTok) with tics or TS. With respect to the phenomenology of tic‐like behaviors, 18 of 20 had complex vocalizations consisting of the repetition of random words or phrases (eg, knock knock, woo hoo, beans); 11 of 20 engaged in the repetition of curse words, or obscene, offensive, or derogatory statements; 13 of 20 had complex arm/hand movements (clapping, pointing, sign language, or throwing objects); and 14 of 20 had complex behaviors in which they would hit or bang part of their body, other people (typically parents), or objects.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical features of registry participants. Participants with FTLBs were more likely to be female, were older at first visit, were older at symptom onset, had higher YGTSS total tic and impairment scores, were more likely to have an anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder diagnosis, and had significantly higher total symptom scores on the MASC2 and CDI2 (all P < 0.0001). Logistic regression controlling for age and sex demonstrated a significant association between the diagnosis of FTLBs and the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder (odds ratio [OR] 4.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.22, 16.00, P = 0.02) or major depressive disorder (OR 4.92, 95% CI 1.29, 18.83, P = 0.02). Linear regression controlling for age and sex demonstrated a significant relationship between the diagnosis of FTLBs and total tic severity on the YGTSS, with a coefficient of 10.60, 95% CI 5.89, 15.30, P < 0.0001.

TABLE 1.

Calgary tic disorders registry comparison of clinical and demographic features

| Variable | Primary tic disorder N = 270 | Rapid onset functional tic‐like behaviors N = 20 | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, proportion | 58 (21%) | 19 (95%) | <0.0001 |

| Age at first clinical visit (mean and 95% CI) | 10.5 y (10.1, 10.9) | 14.3 y (13.5, 15.0) | <0.0001 |

| Age at tic onset (mean and 95% CI) | 6.4 y (6.1, 6.8) | 13.9 y (13.1, 14.7) | <0.0001 |

| YGTSS total tic score | 18.4 (17.4, 19.5) | 33.3 (28.7, 38.0) | <0.0001 |

| YGTSS impairment score | 15.8 (14.2, 17.3) | 28.6 (23.1, 34.1) | 0.0001 |

| ADHD diagnosis, proportion | 120 (44%) | 5 (25%) | 0.09 |

| Conners 3 Inattention Subscale T score | 65.2 (63.3, 67.1) | 68.9 (61.1, 76.8) | 0.16 |

| Conners 3 Hyperactivity Subscale T score | 67.9 (66.0, 69.9) | 64.8 (57.3, 72.3) | 0.21 |

| OCD diagnosis, proportion | 51 (19%) | 1 (5%) | 0.12 |

| CYBOCS score | 5.1 (4.1, 6.1) | 2.7 (0.9, 13.1) | 0.22 |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis, proportion | 51 (19%) | 15 (75%) | <0.0001 |

| MASC2 total T score | 57.4 (55.3, 59.5) | 71.0 (64.6, 77.4) | <0.0001 |

| Depression diagnosis, proportion | 11 (4%) | 11 (55%) | <0.0001 |

| CDI2 total T score | 58.0 (55.5, 60.4) | 74.3 (68.2, 80.5) | <0.0001 |

| Autism diagnosis, proportion | 16 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.26 |

| α‐Agonist treatment, proportion | 55 (21%) | 7 (35%) | 0.13 |

| Antipsychotic treatment, proportion | 40 (15%) | 3 (15%) | 0.99 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, proportion | 44 (16%) | 9 (45%) | 0.002 |

| Stimulant treatment, proportion | 56 (21%) | 3 (15%) | 0.53 |

Calgary Tic Disorders Clinical Registry comparison of clinical and demographic features of primary tic disorder cases with rapid onset functional tic‐like behaviors.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive‐compulsive disorder; CYBOCS, Children's Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; MASC2, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children version 2; CDI2, Child Depression Inventory version 2.

Viewpoint

Although FTLBs have certainly been described by others in the past, 2 , 3 , 4 until now these cases have represented a small fraction of referrals to TS/tic disorder clinics. 2 , 3 , 5 Table 2 provides the estimates on the percentage of new referrals for which functional tics were the primary problem both before the pandemic and in the first half of 2021, and the average annual number of referrals for tics or movement disorders, across five of our centers. Although after the pandemic started referral volumes increased in three centers, remained the same in one center, and decreased in one center, all centers experienced a dramatic increase in the proportion of referrals for FTLBs. Although in the past we have managed children with TS with functional tics in addition to tics related to TS, and observed a small number of functional tic patients each year as the primary diagnosis, it is the unprecedented increase in new referrals of young females with the rapid onset of tic‐like behaviors since the pandemic started that has been so unusual. This has allowed us to record new observations and gather insights into this specific presentation. Many of these rapid onset patients have no definite history of previous tics. They experience the rapid onset of complex tic‐like behaviors that escalate in frequency and severity over a period of hours to days, prompting emergency department visits and even hospital admission. Their presentation is notable for complex motor tic‐like behaviors and vocalizations, with a relative lack of classic simple motor and/or phonic tics and the absence of the expected rostrocaudal progression at onset, 6 characteristic of primary tic disorders. Common manifestations include large‐amplitude arm movements, hitting objects, hitting/punching self or family members, clicking, whistling, repeating a wide range of random and/or bizarre words or phrases, and blurting out obscenities or offensive statements. In many cases, a premonitory urge before these tic‐like behaviors is endorsed, as are distractibility and suggestibility. However, suppressibility of tic‐like behaviors is more limited and variable between individuals. The magnitude of functional disability and level of parental distress caused by the tic‐like behaviors are extreme. Family functioning is often dramatically affected and disrupted. Moreover, many of these young people can no longer attend school or work due to symptom manifestation but are able to perform some activities of daily living (eg, utilization of smartphones, computers, creative projects).

TABLE 2.

Estimated proportion of referrals for FTLBs and average annual new patient referrals for tics/movement disorders, pre‐ and post‐COVID‐19 pandemic

| Center | Pre‐pandemic: estimated percentage of referrals for FTLBs as the primary problem | January–June 2021: estimated percentage of referrals with FTLBs as the primary problem | Pre‐pandemic: average number of referrals received per year for tics/movement disorders | 2020–2021: average number of referrals received per year for tics/movement disorders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary Alberta Children's Hospital Tourette Clinic | 1–2 | 30 | 186 | 290 |

| Sydney Children's Hospital at Westmead Tic Clinic | 2–5 | 35 | 82 | 116 |

| Tic and Neurodevelopmental Movements (TANDeM) Evelina London Children's Hospital Guy's and St. Thomas' (GSTT) MD | 2 | 30 | 300 | 600 |

| Cincinnati Children's Movement Disorders Clinic | 1 | 20 | 600 | 600 |

| UCLA Child OCD, Anxiety and Tic Disorders Program | 2 | 20 | 92 | 71 |

Abbreviations: FTLBs, functional tic‐like behaviors; OCD, obsessive‐compulsive disorder.

The phenomenology of these rapid onset cases represents a noticeable departure from the usual demographic and natural history of TS (see Table 3). Tic onset in TS typically occurs between ages 4 and 7 years. Boys are disproportionately affected, by a ratio of over three to one. 7 Tics typically begin insidiously, with young children usually having a few different tics at a time that wax and wane and evolve in character. In early years, tics are mostly simple, for example, eye blinking, nose wrinkling, facial grimacing, sniffing, throat clearing, or coughing. Complex tics may emerge later, over a period of months to years, but typically after simple tics have been present for some time. Tics often worsen in preadolescence (ages 10–12 years) and improve in late adolescence. 8 Other typical characteristics of tic disorders, such as the report of premonitory sensations or urges to perform tics, subsequent relief of urges after the tic, suggestibility, and distractibility, can be present in association with both tics (more so in adolescents than in children 9 , 10 ) and FTLBs and may therefore be less useful in differentiating between these two groups of patients. At difference, an ability to suppress or postpone tics at least briefly is usually demonstrated in older children with “typical” tics, whereas suppressibility of FTLBs appears to be less efficient. The associated psychiatric comorbidity pattern in these rapid onset cases also differs from TS. The most common comorbid disorders in children diagnosed with TS are ADHD and OCD. 11 In the rapid onset cases, there is a higher representation of anxiety disorders and major depression.

TABLE 3.

Side‐by‐side comparison of phenomenological presentation of tics and rapid onset FTLBs

| Typical TS tics | Rapid onset FTLBs | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | Childhood | Adolescence or early adulthood |

| Symptom onset | Gradual | Abrupt/acute |

| Initial type of tic | Simple motor | Complex motor or complex vocal |

| Sex | Male predominance | Female predominance |

| Most common tics |

Eye blinking Head movements Sniffing Throat clearing |

Large‐amplitude arm movements Self‐injurious movements (eg, hitting self or family members) Wide range of odd words or phrases Obscene words or phrases |

| Most common comorbidities |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Obsessive‐compulsive disorder |

Anxiety disorders Depressive disorders |

| First‐line treatment approach |

CBIT Exposure and response prevention α‐Adrenergic agonists |

Psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, CBIT, with particular emphasis on the functional interventions—identification and management of antecedents and consequences of FTLBs |

Abbreviations: FTLBs, functional tic‐like behaviors; TS, Tourette syndrome; CBIT, Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics.

Although most young people with this rapid onset of tic‐like behaviors have not reported any history of previous tics, we have witnessed several young patients with a history of mild simple tics who reported an explosive onset of complex tic‐like behaviors during the same period. Age, sex distribution, phenomenology, and type of onset in this less‐represented subgroup are similar to the majority of youth with rapid onset of complex tic‐like behaviors without previous history of tics. This similarity intriguingly suggests the possibility of shared predisposing factors in these two subgroups. This presentation differs substantially also from other acute syndromes in which tics or tic‐like movements are predominant. In particular, we did not notice any association with recent upper‐respiratory/pharyngeal infections or acute obsessive‐compulsive spectrum symptoms (eg, those observed in pediatric acute onset neuropsychiatric syndromes), and the phenomenology was not consistent with acute drug‐induced movement disorders.

Another relevant characteristic of this new clinical presentation is the association with specific psychosocial stressors, the exposure to which may have increased substantially during the COVID‐19 pandemic in this age group. A proportion of these patients reported family‐related emotional distress linked to tensions between parents or other family members, which may have been exacerbated by the lockdown. Other patients have described a temporal association between symptom onset and increased stress levels related to “virtual schooling,” meeting academic expectations, and navigating school–home transitions that are accompanied by several academic challenges.

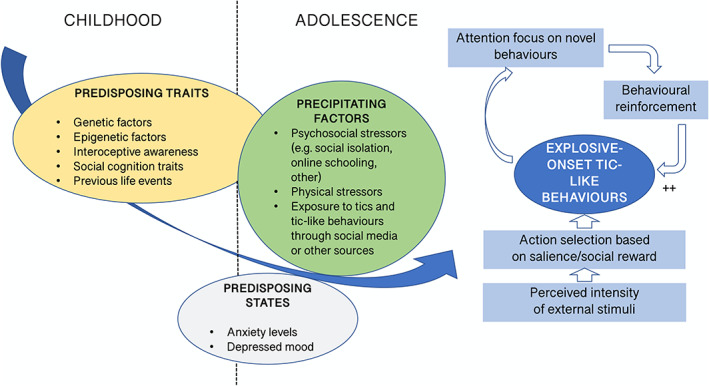

What could be at the origin of this specific, explosive presentation of tic‐like behaviors, and why is it occurring now? Recently, there has been a growth in online video material of youth manifesting tic disorders, shared on social networks. In some cases, these videos were pooled under thematic hashtags focused on TS and yielded exponentially increasing popularity at the beginning of 2021. Interestingly, we and others 1 , 12 , 13 have noticed a phenomenological similarity between the tics or tic‐like behaviors shown on social media and the tic‐like behaviors of this group of patients. In some cases, the patients specifically identified an association between these media exposures and the onset of symptoms, although, with some of the younger children, the social media use was disclosed only after careful questioning. The COVID‐19 pandemic has been a major source of stress and anxiety for people globally, resulting in increased mental health symptoms and demand for mental health services. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Increased social isolation and the widespread utilization of social media may have contributed as precipitating factors in a relevant proportion of these patients. External factors like watching popular social media personalities' videos portraying tics or tic‐like behaviors may have instilled a belief that “tics” may catalyze peer acceptance or even popularity. This exposure to tics or tic‐like behaviors is a plausible trigger for the behaviors observed in at least some of these patients, based on a disease modeling mechanism. However, this specific social media exposure to tic‐related videos, although reported in all patients in the Calgary series, was not reported in every patient treated at all the other centers, suggesting that it cannot be considered a prerequisite or necessary causative factor. There is a need for systematic investigation of the relationship between symptom onset, severity, and amount of social media exposure. The explosive behavioral pattern exhibited by these young people could also share pathophysiological mechanisms with the general population of people with FTLBs, as proposed in greater detail in Figure 1.

FIG 1.

Possible pathophysiological mechanisms for the functional tic‐like behaviors (FTLBs) exhibited by this group of patients. As recently proposed in the context of FTLBs, 19 a combination of predisposing traits (encompassing, among others, genetic and epigenetic factors and previous life events), predisposing states (eg, raised anxiety levels and related low mood), and environmental precipitating factors (increase in media exposure to tic‐like behaviors, different stressors driven by the pandemic) may prompt an excess of behavioral alterations, such as recurrent tic‐like behaviors. In specific groups of people like those whom this viewpoint is focusing on, the environment might be providing the individual with overabundant external stimuli that may be discerned as highly salient (ie, attractive and “popular” tics or tic‐like behaviors). Such behaviors will be selected and reinforced, and the individual will, particularly at an initial learning stage, allocate an excess of attention to them, thereby enhancing their probability of recurrence reinforcement. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A comprehensive interview of patients, families, and relevant informants is a first, necessary step to understand the antecedents and triggering factors involved, which will allow deeper understanding of this clinical picture and guide personalized management decisions. Comparisons to historical precedents of similar outbreaks at a more local level are also useful. For example, a regional outbreak of tic‐like behaviors was documented in adolescent girls in 2012 in Le Roy, New York, which was attributed to a combination of conversion disorder and mass psychogenic illness. 19

As our familiarity with this behavioral pattern increases through clinical experience, we need to explore in depth the psychopathological profile of these patients, as well as identify recurrent predisposing family‐ and peer‐related stressors. It would also be relevant to investigate social and adaptive functioning as well as social cognition domains, particularly the processing of socially salient stimuli, their perception, and integration of reward mechanisms related to social cues. Finally, a striking characteristic of this behavioral pattern is its “epidemic” diffusion over a relatively short time, which differs from the slower pace of referral to specialists' attention of FTLBs and indicates the involvement of suggestibility and behavioral modeling. In this respect, it would be useful to explore whether abnormalities in sense of agency and action monitoring, similar to those observed in people with other functional neurological disorders, are a consistent trait also in these patients or whether performance on these domains is more variable.

We wish to bring neurologists' attention to this emerging disorder and highlight the important phenotypic differences these cases have from typical cases of TS. A prompt diagnosis and expert review to clarify the phenomenology when necessary is recommended. We also acknowledge that diagnostic labeling may be difficult when childhood onset simple tics and the more complex types of rapid onset FTLBs, coexist in the same patient. 20 Our initial, anecdotal experience is that these patients do not respond typically to conventional pharmacotherapies for tics, either showing dramatic improvement within hours or days of starting an α‐agonist (suggestive of a placebo response) or having no response whatsoever to antipsychotic medications with demonstrated high efficacy for tics. 21 Behavioral treatment approaches, including personalized psychoeducation, seem more appropriate to initiate a therapeutic process. Intuitively, function‐based therapeutic strategies, 22 , 23 , 24 including mitigating potential triggering exposures, particularly social media content associated with tics, initiating stress management interventions related to other identifiable psychosocial stressors, reducing social reactions to symptom expression, and addressing comorbid anxiety and depression, could be confirmed as high‐yield strategies by future observations. Our prediction is that cognitive behavioral therapies, particularly when including components of the Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics, 25 might have a considerable chance of success to treat this type of repetitive behavior.

Author Roles

(1) Tamara Pringsheim: conception and design, data acquisition or analysis, drafting, editing, revising text; (2) Christos Ganos: conception, drafting, editing, revising; (3) Joseph McGuire: drafting, editing, revising; (4) Tammy Hedderly: drafting, editing, revising; Doug Woods: drafting, editing, revising; (5) Donald Gilbert: drafting, editing, revising; (6) John Piacentini: drafting, editing, revising; (7) Russell Dale: drafting, editing, revising; (8) Davide Martino: conception and design, data acquisition, drafting, editing, revising.

Full financial disclosure for the previous 12 months

Tamara Pringsheim has received grant funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada and Alberta Health.

Christos Ganos holds a research grant from the VolkswagenStiftung (Freigeist Fellowship) and has received honoraria from the Movement Disorder Society for educational activities.

Joseph F. McGuire reports receiving research support from the Tourette Association of American (TAA), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), the American Psychological Foundation (APF), and the Hilda and Davis Preston Foundation. He has served as consultant to Bracket Global, Syneos Health, and Luminopia and has also received royalties from Elsevier.

Tammy Hedderly has no financial disclosures.

Douglas Woods has received book royalties from the Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Springer Press and has received speaker's fees from the Tourette Association of America.

Donald L. Gilbert has received honoraria and/or travel support from the Tourette Association of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Child Neurology Society, and the American Academy of Neurology. He has received compensation for expert testimony for the U.S. National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, through the Department of Health and Human Services. He has received payment for medical expert opinions through Advanced Medical/Teladoc. He has served as consultant for Applied Therapeutics and Eumentics Therapeutics. He has received research support from the NIH (NIMH) and the DOD. He has received salary compensation through Cincinnati Children's for work as a clinical trial site investigator from Emalex (clinical trial, Tourette Syndrome) and EryDel (clinical trial, ataxia telangiectasia). He has received book/publication royalties from Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer, and the Massachusetts Medical Society.

John Piacentini has no financial disclosures.

Russell C. Dale has National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator fellowship and Cerebral Palsy Alliance funding.

Davide Martino has no conflicts of interest to report. Davide Martino has received compensation for consultancies for Sunovion; honoraria from Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada; royalties from Springer‐Verlag; research support from Ipsen Corporate; and funding grants from Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada, Parkinson Canada, The Owerko Foundation, and the Michael P. Smith Family.

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report in relation to research covered in this article.

Funding agency: None.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Heyman I, Liang H, Hedderly T. COVID‐19 related increase in childhood tics and tic‐like attacks. Arch Dis Child 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-321748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganos C, Edwards MJ, Müller‐Vahl K. "I swear it is Tourette's!": on functional coprolalia and other tic‐like vocalizations. Psychiatry Res 2016;246:821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Demartini B, Ricciardi L, Parees I, Ganos C, Bhatia KP, Edwards MJ. A positive diagnosis of functional (psychogenic) tics. Eur J Neurol 2015;22(3):527–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baizabal‐Carvallo JF, Jankovic J. The clinical features of psychogenic movement disorders resembling tics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85(5):573–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rakesh K, Kamble N, Yadav R, Bhattacharya A, Holla VV, Netravathi M, et al. Pediatric functional movement disorders: experience from a tertiary care Centre. Can J Neurol Sci 2021;48(4):518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ganos C, Bongert J, Asmuss L, Martino D, Haggard P, Münchau A. The somatotopy of tic inhibition: where and how much? Mov Disord 2015;30(9):1184–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pediatr Neurol 2012;47(2):77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, Lahnin F, Lynch K, Bondi C, et al. Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. Pediatrics 1998;102(1 Pt 1):14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sambrani T, Jakubovski E, Müller‐Vahl KR. New insights into clinical characteristics of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: findings in 1032 patients from a single German center. Front Neurosci 2016;10:415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banaschewski T, Woerner W, Rothenberger A. Premonitory sensory phenomena and suppressibility of tics in Tourette syndrome: developmental aspects in children and adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol 2003;45(10):700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, Dion Y, Grados MA, Illmann C, et al. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiat 2015;72(4):325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hull M, Parnes M. Tics and TikTok: functional tics spread through social media. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 10.1002/mdc3.13267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hull M, Parnes M, Jankovic J. Increased incidence of functional (psychogenic) movement disorders in children and adults amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study. Neurology 2021. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daly M, Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in psychological distress in the UKfrom 2019 to September 2020 during the COVID‐19 pandemic: evidence from a large nationally representative study. Psychiatry Res 2021;300:113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daly M, Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic: population‐based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord 2021;286:296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rossi R, Jannini TB, Socci V, Pacitti F, Lorenzo GD. Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID‐19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psych 2021;12:635832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vigo D, Jones L, Munthali R, Pei J, Westenberg J, Munro L, et al. Investigating the effect of COVID‐19 dissemination on symptoms of anxiety and depression among university students. BJPsych Open 2021;7(2):e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wong LP, Alias H, Md Fuzi AA, Omar IS, Mohamad Nor A, Tan MP, et al. Escalating progression of mental health disorders during the COVID‐19 pandemic: evidence from a nationwide survey. PLoS One 2021;16(3):e0248916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dominus S. What happened to the girls in Le Roy. New York Times Magazine, March 11, 2012.

- 20. Ganos C, Martino D, Espay AJ, Lang AE, Bhatia KP, Edwards MJ. Tics and functional tic‐like movements: can we tell them apart? Neurology 2019;93(17):750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pringsheim T, Holler‐Managan Y, Okun MS, Jankovic J, Piacentini J, Cavanna AE, et al. Comprehensive systematic review summary: treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology 2019;92(19):907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woods DW, Piacentini J, Chang S, Deckersbach T, Ginsburg GS, Peterson AL, et al. Managing Tourette Syndrome. A Behavioral Intervention for Children and Adults. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chouksey A, Pandey S. Functional movement disorders in children. Front Neurol 2020;11:570151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. LaFaver K. Treatment of functional movement disorders. Neurol Clin 2020;38(2):469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Chang S, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303(19):1929–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.