Abstract

Outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic is testing governments' capacity. Generally, considerable attention is paid to the capacity and response of the central or national governments; however, COVID‐19 pandemic is local in nature. Although central authorities have important roles to play in COVID‐19 response, local governments, being closer to people, are best‐positioned to form the first line of defense.

Keywords: governance, local public service delivery, municipalities, Nepal

1. INTRODUCTION

In Nepal, the outbreak of coronavirus pandemic has put the fledgling federal system to a test. Nepal's federal system was put in place with the adoption of the 2015 Constitution. After embarking on a full‐fledged federal system after years of conflict, the country has made significant progress in establishing key institutional structures, such as provincial and local governments before the coronavirus pandemic. These newly established subnational governments have joined the efforts of the federal government to contain the spread of the disease and limit the number of causalities.

In Nepal, the crisis highlights glaring weaknesses in the intergovernmental system. Initial research highlights an alarming pattern of high levels of cases and mortality among the younger cohorts of the population (Banerjee et al., 2020). The recent upward trend in the number of COVID‐19 cases is worrisome. However, the uptick in the COVID‐19 cases is in localized clusters and there is a big variation across provinces. For instance, there has been a flattening of cases in Provinces 6 (Karnali) and 7 (Sudupashchim), whereas in Provinces 3 (Bagmati) and 5 there is an upward trend. Interestingly, there is an increase in the number of women who have tested positive compared to the initial period of the pandemic.

2. FEDERAL SYSTEM

Nepal is one of the most diverse countries in the world. There are 126 ethnic groups and castes speaking 123 languages as mother tongue reported in the census 2011. The country is divided into three regions by topography: the Himalayan (mountains), the hills, and the Terai (plain land).1

Nepal was engulfed in a decade‐long insurgency and bloodshed, which led to the removal of the constitutional monarchy in May 2008. The 2007 Interim Constitution identified federalism as a solution to the conflict and emphasized devolution of power to subnational governments. In line with the provisions of the Interim Constitution, the 2015 Constitution established a federal democratic state with three levels of government.

Following the adoption of the Constitution, seven provinces have been established. Upon the recommendations of the Local Level Restructuring Commission, the boundaries of existing 3157 village development committees and 217 municipalities—spread across 77 districts—were consolidated into 753 rural and urban local government units. The first local level elections in 20 years took place in 2017.2 In addition to the local elections, the provincial and federal elections were completed by January 2018. Subnational governments in Nepal play an important role in terms of public service delivery and quality of governance, both of which were critical factors in mitigating conflict in the country.

While public health policy is the main responsibility of federal and provincial governments, local governments are exclusively responsible for primary healthcare and sanitation (Dhrubaraj, 2020). However, the constitution does not specifically mention pandemic management and response in relation to the distribution of powers among the three levels of government. Nonetheless, the constitutional mandate for primary healthcare responsibility gives the legal basis to local governments to enact local healthcare and sanitation act to fight against the pandemic. Many local governments enacted these local laws based on powers enumerated in the constitution and national legislations for primary healthcare service provision. In addition, local governments declared public health emergency and activated their disaster management committees3 to ensure that citizens receive emergency services at any healthcare institution within the municipality.

Notwithstanding the progress in the implementation of federalism, Nepal's federal system is still fragile and incomplete. Although much has been accomplished, there is still much to be done (Government of Nepal, 2019). There are overlapping mandates and coordination failures in addition to weaknesses in institutional capabilities. In order to achieve better coordination across levels of government, the parliament needs to update legislative framework to reflect federalism principles in the assignment responsibilities. In that context, the most pressing issue is updating sector legislations and enactment of a modern pandemic act to improve coordination between levels of government. Currently, an outdated legislation, the Panchayat‐era Infectious Disease Act of 1964, empowers the central government and its deconcentrated structures in an epidemic situation, ignoring provincial and local governments established after transition to federal system. The Supreme Court of Nepal has recently instructed the government to evaluate the existing legislations related to health emergencies and enact a new pandemic act.4 In its ruling, the high court clearly stated that the existing laws are insufficient to address important health and social issues surrounding coronavirus pandemic, different levels of government setting different standards and issuing conflicting orders. A good example of conflict between different levels of governments is mobility restrictions introduced by district authorities and opposed by the municipal government in Kathmandu (Ojha, 2020).

3. CORONAVIRUS RESPONSE

The coronavirus pandemic has presented a defining challenge to the nation's nascent federal system. Although initially the majority of the COVID‐19 cases had been imported from other countries (Chalise, 2020), they began to spread to all seven provinces. The first major community outbreaks were observed in the eastern (Udaypur), western (Banke), and central (Bitguni) regions (Chalise, 2021). Afterward the epicenter of the pandemic shifted to Kathmandu, where half of the national cases are reported (Chalise, 2021).

Initially, the public health measures—social distancing, lockdowns, personal hygiene, and border controls—helped in preventing the spread. However, the effectiveness of these measures has not been observed and the number of cases surged (Dhakal & Karki, 2020). A contributing factor had been the return of daily wage migrant workers from India, where Nepal shares open border with. Nepalese, desperate to return home, evaded border controls by swimming across the Mahakali River (Badu, 2020). All three tiers of government struggled to cope with the influx of people returning home from India. In addition, there was a significant volume of in‐country movement as workers returned to their hometown after employment opportunities dwindled in urban centers due to lockdowns (Dhakal & Karki, 2020). The government came under criticism for its slow response (Koirala et al., 2020; Shakya, 2020).

Under heavy pressure from the public, all levels of government increased their efforts to bring the spread of the disease under control. While national government instituted the nationwide lockdown,5 subnational governments—local governments in particular—have led the country's public health response, providing essential information and distributing relief.

The federal government established a COVID‐19 Crisis Management Center, after the botched attempt of creating an ad hoc mechanism.6 In all seven provinces, a provincial disaster management committee has been activated to coordinate with the federal government. In addition, the federal government established a COVID‐19 Prevention, Control and Treatment Fund (COVID‐19 Fund) at the federal level, which was replicated at the provincial and local levels.7

As the coronavirus began to spread across the country, local governments took the lead in the fight against the virus. According to a recent study, the efforts of subnational governments are decisive factor in keeping COVID‐19 cases under control (Foundation for Development Management and Nepal Institute for Policy Research, 2020). Provincial and local governments are a critical part of the coronavirus response as they play important roles in four areas:

Increasing the level of local public health service delivery: In Nepal, provincial and local governments are directly or indirectly involved in the provision of local public health services. For example, to tackle with the recent uptick in the number COVID‐19 cases, the federal government is working with the provincial governments to expand isolation beds by using the hospitals not currently designated for COVID treatment, existing quarantine sites, and hotels. In Sudurpashchim Province, local governments ordered thermal cycler (also known as polymerase chain reaction testing machine) to increase testing capacity. In addition, they are in the process of establishing a temporary coronavirus hospital in Tikapur.

Preventing transmission and epidemiological investigations and tracking: Provincial and local governments play an important role in preventing transmission of the disease and help the federal government's efforts to conduct epidemiological investigations. Epidemiological investigations teams and health desks have been established at major border checkpoints with India and around cities such as Kathmandu, Lumbini, Chitwan, Pokhara, Bhairahawa, and Ilam (Shrestha et al., 2020). Local governments are particularly proactive in prohibiting public gatherings, establishing information centers, setting up handwashing systems, allocating isolation beds, and instituting quarantine procedures at public and private hospitals. In many localities, local governments launched information campaigns to educate people of preventive measures to fight the virus. The Dhangadhi sub‐metropolitan city, for example, issued a notice calling on the public to avoid large gatherings. In Tikapur municipality, for instance, the municipal government established health desks to provide information and health checkups to migrant workers returning from India. Similarly, in Dhading municipality, local authorities established health desks for the prevention of COVID‐19 and monitored people who came into the municipality from other localities. The volunteers and health workers deployed by the local governments are screening people for fever and other symptoms. In addition, local governments are helping provincial governments by collecting data in terms of number of the people in quarantine/isolation, returned from abroad,8 and needing relief. As provincial and local governments set up isolation and quarantine facilities, the federal government focuses on treatment of patients.

Mitigating the impact of the pandemic on other local public services: Provincial and local governments play an important role in reviewing and adjusting (and in some cases, temporarily suspending) the provision of public services to reduce the spread of the virus. After the federal government decision to close schools, local governments enforced the decision to stop the spread of the virus.

Supporting social and economic relief activities: In order to fund the response activities, both provincial and local governments have established disaster management funds, such as municipalities of Madhyapur, Makwanpur, Kamalamani, and Sailung in Bagmati Province. The provincial governments are also allocating additional funds to local governments to reinforce their efforts. In addition, local governments have been allowed to allocate resources to fight COVID‐19 from their equalization grants.

4. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COVID‐19 CASE FATALITY AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT STRENGTH

As local governments take a prominent role in responding to coronavirus pandemic, we analyze the relationship between COVID‐19 cases, deaths, and local government capacity. In the analysis, we use multiple sources of data. However, reporting of COVID‐19 cases and local government capacity are at two different levels. COVID‐19 data are reported at the district level whereas local government capacity information is at the local government level.8

Local government capacity data are from the Nepal Capacity Assessment for the Transition to Federalism.9 The assessment aimed at identifying the strengths and weaknesses of provincial and local governments to manage the service delivery responsibilities assigned to them under the Constitution.

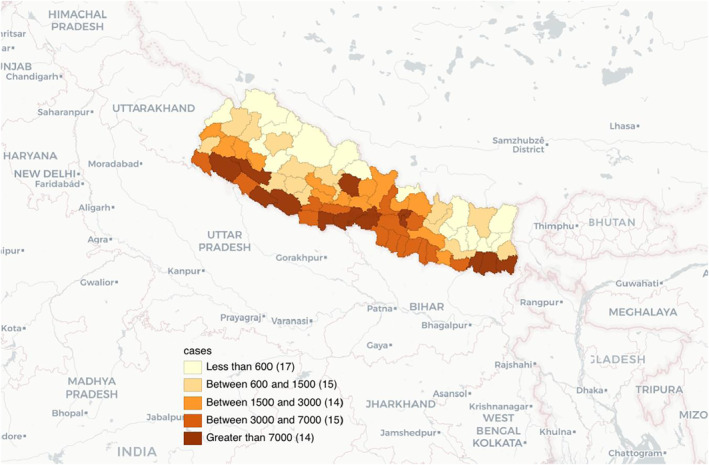

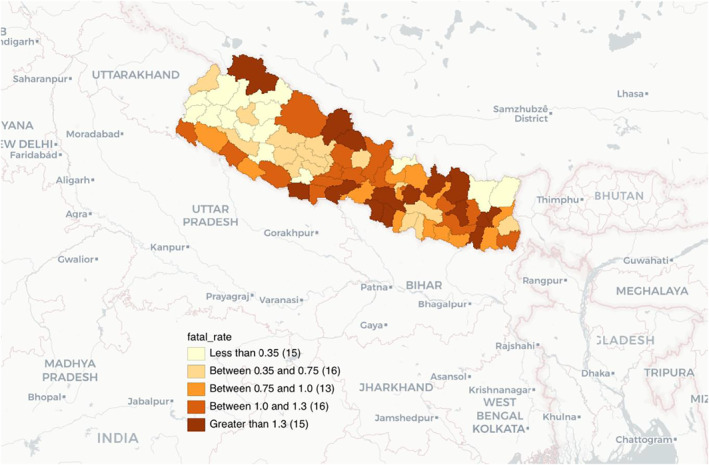

Data for COVID‐19 cases are reported on the Federal Ministry of Health and Population website at the district level.10 Since COVID‐19 data are only available at the district level, we had to adjust the local government capacity indicators to the district level by taking the average of local governments' score in a district. We provide the summary statistics for the variables we use in Table 1, including COVID‐19 cases, case fatality rate, and some of the capacity assessment survey variables for local government planning and social inclusion. We also show total COVID‐19 cases and the COVID‐19 case fatality rate (deaths/total cases) in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows total COVID‐19 cases in the Nepalese districts. We see a clear pattern with cases clustered in those districts in the Plains region that are close to the border with India, which is a country that has so far experienced one of the largest COVID‐19 outbreaks in the world. The map shows that while the majority of the districts don't show any serious virus transmission, there are 49 districts, mainly along the border with India, with more than 1000 cases. Figure 2 shows that the case fatality rate is also high (greater than 1%) in 31 districts, including some along the border with India and others in the Hills region and the Mountain region along the border with China.

TABLE 1.

COVID‐19 and selected local government survey statistics from districts in provinces

| Obs | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 62 districts with LG data | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases (total) | 62 | 7265 | 21,674 | 55 | 167,411 |

| Case fatality rate (%) | 62 | 0.850 | 0.495 | 0 | 2.169 |

| LG economic development plan | 61 | 0.643 | 0.393 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 62 | 0.806 | 0.356 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 62 | 0.378 | 0.044 | 0.2 | 0.431 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 62 | 0.809 | 0.315 | 0 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 62 | 0.816 | 0.328 | 0 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 1 | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases (total) | 13 | 3555 | 6288 | 262 | 20,348 |

| Case fatality rate (%) | 13 | 1.086 | 0.583 | 0 | 2.169 |

| LG economic development plan | 13 | 0.897 | 0.199 | 0.5 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 13 | 0.846 | 0.315 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 13 | 0.366 | 0.065 | 0.2 | 0.421 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 13 | 0.846 | 0.25 | 0.333 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 13 | 0.769 | 0.388 | 0 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 2 | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 8 | 4036 | 1481 | 2901 | 6761 |

| Case fatality rate | 8 | 0.969 | 0.413 | 0.656 | 1.738 |

| LG economic development plan | 8 | 0.885 | 0.16 | 0.667 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 8 | 0.363 | 0.057 | 0.231 | 0.412 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 8 | 0.958 | 0.118 | 0.667 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 8 | 0.927 | 0.137 | 0.667 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 3 (Bagmati) | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 10 | 23,258 | 51,331 | 1173 | 167,411 |

| Case fatality rate | 10 | 1.042 | 0.288 | 0.573 | 1.504 |

| LG economic development plan | 10 | 0.5 | 0.342 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 10 | 0.717 | 0.416 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 10 | 0.374 | 0.045 | 0.281 | 0.429 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 10 | 0.767 | 0.344 | 0 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 10 | 0.883 | 0.193 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 4 (Gandaki) | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 5 | 5560 | 5935 | 972 | 15,296 |

| Case fatality rate | 5 | 0.891 | 0.419 | 0.412 | 1.314 |

| LG economic development plan | 5 | 0.333 | 0.408 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 5 | 0.667 | 0.471 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 5 | 0.401 | 0.024 | 0.374 | 0.424 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 5 | 0.8 | 0.298 | 0.333 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 5 | 0.8 | 0.298 | 0.333 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 5 | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 11 | 6851 | 7451 | 688 | 23,658 |

| Case fatality rate | 11 | 0.828 | 0.381 | 0.315 | 1.459 |

| LG economic development plan | 11 | 0.485 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 11 | 0.727 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 11 | 0.398 | 0.018 | 0.371 | 0.431 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 11 | 0.697 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 11 | 0.864 | 0.323 | 0 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 6 (Karnali) | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 8 | 1424 | 2426 | 55 | 7146 |

| Case fatality rate | 8 | 0.496 | 0.545 | 0 | 1.408 |

| LG economic development plan | 7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 8 | 0.75 | 0.463 | 0 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 8 | 0.367 | 0.024 | 0.333 | 0.396 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 8 | 0.75 | 0.463 | 0 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 8 | 0.688 | 0.458 | 0 | 1 |

| Districts in Province 7 (Sudurpashchim) | |||||

| COVID‐19 cases per 1000 persons | 7 | 3487 | 3895 | 762 | 11,974 |

| Case fatality rate | 7 | 0.406 | 0.407 | 0.054 | 1.068 |

| LG economic development plan | 7 | 0.714 | 0.393 | 0 | 1 |

| LG disaster plan | 7 | 0.929 | 0.189 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Share of female members in the local assembly | 7 | 0.389 | 0.024 | 0.366 | 0.429 |

| LG social inclusion policy for gender | 7 | 0.881 | 0.209 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Framework for women's participation in LG activities | 7 | 0.762 | 0.418 | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviation: LG, local government.

Source: Nepal Ministry of Health and Population (COVID data for May 12, 2021) and Nepal Capacity Assessment for the Transition to Federalism (2019).

FIGURE 1.

Total COVID‐19 cases in Nepalese districts. Source: Nepal Ministry of Health and Population (COVID data for May 12, 2021)

FIGURE 2.

COVID‐19 case fatality rates in Nepalese districts. Source: Nepal Ministry of Health and Population (COVID data for May 12, 2021)

We see in Table 1 that while the case fatality rate is less than 1% for the country, there is significant variation across provinces. There is also a significant variation in the survey variables. We find it interesting that those provinces with higher share of local government development and local disaster plans tend to have lower case fatality rates. For example, about 93% of local governments in the Sudurpashchim Province (Province 7) have a local disaster plan. That province also has so far the lowest average case fatality rate among all provinces. This is in stark contrast with the Bagmati Province (Province 3) which has only about 72% of local governments with local disaster plans and the highest COVID‐19 case number and second highest case fatality rate that is more than twice as high as the one in Sudurpashchim. Sudurpashchim Province also has some of the highest indicators of women's participation in local governance as seen by the share of female members in the local assembly, social inclusion mechanism for gender, and the framework for women's participation in local government activities.

5. CONCLUSION

In Nepal, the response to the COVID‐19 pandemic is impacted by the lack of test kits, medical supplies, personal protective equipment, and well‐trained healthcare personnel. Initial failures in coordination mechanisms among stakeholders and poor reporting and documentation of cases hampered the progress in government's response. The pandemic highlighted the importance of a robust healthcare and the government is preparing a strategy to enhance health service in the country (Pant, 2020).

The case of Nepal highlights the importance of coordination and cooperation across levels of government. All‐of‐government, federal–provincial–local, response is a critical factor in the success of the fight against the COVID‐19 pandemic. Despite the fact that newly established subnational governments face capacity constraints, they are at the forefront of the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. A recent assessment of subnational governments' response highlights that they were able to mobilize resources for localized solutions (Foundation for Development Management and Nepal Institute for Policy Research, 2020). Local governments, for example, rapidly enacted their own local healthcare and sanitation acts even though the national legislation to manage a pandemic is lacking. In fact, local governments with inclusive structures, such as social inclusion mechanism for gender as well as a framework for women's participation in local government activities, handled the pandemic better than others.

A word of caution about data is that the situation on the ground is still changing rapidly as the pandemic rages on in the region, particularly in neighboring India. We would like to note that we are not making any causal claims based on these findings. With more data in the future, we expect more empirical research on COVID‐19 and local government response in Nepal.

Mainali, R., Tosun, M. S., & Yilmaz, S. (2021). Local response to the COVID‐19 pandemic: The case of Nepal. Public Administration and Development, 41(3), 128–134. 10.1002/pad.1953

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions are entirely those of authors and do not represent the views of the World Bank, its executive directors, or countries they represent.

Footnotes

The upper caste people from Himalaya and hill regions dominate the political system, administrative machine, and business society of the country.

The first phase of the local elections in 20 years was held on May 14, 2017, in 34 districts of Nepal. Following this, local elections were carried out in most of the remaining districts on June 28, 2017, while the elections in Province 2 were postponed to September 18, 2017. With the parliament dissolved on October 13, 2017, the general and provincial elections were held on November 26, 2017 (32 districts) and December 7, 2017 (45 districts).

Nepal's Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act was enacted in 2017 but pandemic is defined as a non‐natural disaster.

The federal government imposed a strict lockdown on March 24 until July 21 in order to keep the virus from spreading.

At the outset of the pandemic, the government had established an ad hoc mechanism, COVID‐19 Prevention and Control High Level Coordination Committee (HLCC), by an executive decision to respond to the crisis. Within less than a month of the formation of the HLCC, the Council of Ministers formed another COVID‐19 Crisis Management Center (CCMC) with a detailed and clear terms of reference, which eventually replaced the HLCC. The CCMC is co‐led by the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defense and included five other senior minsters from the Federal Council of Ministers. A Facilitation Committee to support the CCMC's functions is formed under the leadership of the Chief Secretary, which includes the Secretary of the Federal Ministry of Home Affairs and the Chiefs of four security forces (Nepal Army, Nepal Police, Armed Police Force, and National Investigation Department).

The objective of the COVID‐19 Fund is to support prevention, control, and treatment of COVID‐19 patients, provide relief to the poor and vulnerable, and cover the expenses of infrastructure and human resources directed at COVID‐19 responses. A seven‐member committee led by the Vice‐Chair of the National Planning Commission is formed to operate the Federal COVID‐19 Fund, with the Secretaries of relevant ministries as members. The provincial and local level Funds are each operated by a committee led by Chief Minister and Chairs/Mayors, respectively.

The Department of Foreign Employment issued 1473 reentry permits for foreign employment in major labor destinations such as UAE, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Japan, and Qatar since the resumption of reentry permit services on July 2 (see https://thehimalayantimes.com/business/department‐of‐foreign‐employment‐issues‐nearly‐1500‐re‐entry‐permits‐in‐one‐week/).

The assessment was commissioned by the government and conducted by Georgia State University in partnership with the Nepal Administrative Staff College. Available at: https://www.mofaga.gov.np/uploads/notices/Notices‐20200506153437737.pdf

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Badu, M. (2020). Nepalis are swimming across the Mahakali to get home. Katmandhu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/2/2020/03/30/nepalis‐are‐swimming‐across‐the‐mahakali‐to‐get‐home [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, I., Robinson, J., Kashyap, A., Mohabeer, P., Shukla, A., & Leclézio, A. (2020). The changing pattern of COVID‐19 in Nepal: A global concern—A narrative review. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 10(2), 845–855. 10.3126/nje.v10i2.29769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalise, H. M. (2020). COVID‐19 situation and challenges for Nepal. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 32(5), 281–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalise, H. N. (2021). Fears of health catastrophe as Nepal reports increasing deaths from COVID‐19. Archives of Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5, 001–003. 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, S., & Karki, S. (2020). Early epidemiological features of COVID‐19 in Nepal and public health response. Frontiers in Medicine, 7, 524. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhrubaraj, B. K. (2020). In Nepal, federalism, health policy and the pandemic. https://asiafoundation.org/2020/06/10/in‐nepal‐federalism‐health‐policy‐and‐the‐pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Development Management and Nepal Institute for Policy Research . (2020). Assessment of provincial governments’ response to COVID‐19. http://fdm.com.np/wp‐content/uploads/2020/09/Assessment‐of‐Provincial‐Response‐to‐COVID‐19‐Sep‐8.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nepal . (2019). Nepal: Capacity needs assessment for the transition to federalism. https://www.mofaga.gov.np/uploads/notices/Notices‐20200506153437737.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, J., Acharya, S., Neupane, M., Phuyal, M. R., Rijal, N., & Khanal, U. (2020). Government preparedness and response for 2020 pandemic disaster in Nepal: A case study of COVID‐19. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3564214 [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, A. (2020). Kathmandu wants the local administration to roll back decision to allow footpath vending. Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/valley/2020/09/11/kathmandu‐wants‐local‐administration‐to‐roll‐back‐decision‐to‐allow‐footpath‐vending [Google Scholar]

- Pant, L. D. (2020). Nepal secures US$495 million to construct 396 basic hospitals across the country. Development Aid. https://www.developmentaid.org/#!/news‐stream/post/80412/nepal‐secures‐us495‐million‐to‐construct‐396‐basic‐hospitals‐across‐the‐country [Google Scholar]

- Shakya, M. (2020). The politics of border and nation in Nepal in the time of pandemic. Dialectical Anthropology, 44(3), 223–231. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s10624-020-09599-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R., Shrestha, S., Khanal, P., & Bhuvan, K. C. (2020). Nepal's first case of COVID‐19 and public health response. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(3), 1–2. 10.1093/jtm/taaa024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.