Abstract

The substantial literature in political economy and sociology has shown that the increasing importance of financial activities (financialisation) exhibits significant effects on many socioeconomic conditions. While these conditions are relevant to public health, the dominant focus of the literature has been centred on the impact of financial markets on health services and health‐care systems. This paper analyses how the financialisation of non‐financial corporations, real estate and pensions can worsen public health through the transformation of workplace and living conditions as well as financially dependent social groups' perception of health risk. Our analysis raises several questions which aim to provide the basis of a future research agenda on the effects of financialisation on public and global health.

Keywords: financialisation, inequalities, public health

Abbreviations

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- FRED

federal reserve economic data

- MER

middle east respiratory syndrome

- OECD

organisation for economic co‐operation and development

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

The financialisation of the society and the economy, that is ‘…the increasing importance of finance, financial markets, and financial institutions to the workings of the economy’ (Davis & Kim, 2015), and its socioeconomic effects have gained significant attention during the last decade. More specifically, financialisation can be defined as the increased dominance of financial institutions and motives over the scope and priorities of traditional non‐financial sectors of the economy as well as ordinary people (Martin, 2002). Sociologists (e.g. Carruthers & Kim, 2011; Dwyer, 2018; Keister, 2002; Krippner, 2005; Volscho & Kelly, 2012), as well as political economists (e.g. Epstein, 2005; Orhangazi, 2008; Stockhammer, 2017; van der Zwan, 2014), explore how financialisation influences different aspects of social and economic life, including employment relations and income inequality. Nonetheless, as Hunter and Murray (2019) claim, financialisation affects broader social conditions through shaping social institutions and subjectivities, which lead to new forms of social regulation.

It is well known that health and illnesses are affected significantly by social conditions, which vary across space and time (e.g. Galanis & Hanieh, 2021; Marmot et al., 2008; Weitz, 2001). Over the last 40 years, social conditions across the globe have been greatly influenced by different aspects of globalisation, neoliberalism and financialisation. While recent sociological research has studied several of the effects of neoliberalism – broadly speaking – and globalisation (e.g. Navarro, 2007; Schrecker, 2016; Sparke, 2017), the potential effects of financialisation on public health have been studied almost exclusively in terms of the financialisation of health‐care system. Recent literature focuses on how global private equity funds' investments in health‐care systems and the rise of various health‐care‐related financial instruments have induced the marketisation of the sector, leading to worsening and more unequal health‐care provision (Bailey et al., 2019; Hunter & Murray, 2019; Llewellyn et al., 2020; Rowe & Stephenson, 2016; Stein & Sridhar, 2018; Vural, 2017). The purpose of this article is to propose general research questions on the relationship between financialisation and public health outcomes by identifying key mechanisms related to the financialisation of non‐financial corporations (NFCs), real estate, consumption and pensions.

FINANCIALISATION AND INEQUALITIES

A growing sociological and political economy literature has shown that financialisation exhibits significant effects on many aspects of everyday life, like consumption patterns and housing affordability (Martin, 2002). Furthermore, these aspects affect social conditions which are relevant to health. Identifying and investigating these effects can provide new insights with regard to social determinants of health and, as a result, ways to improve public and global health. First, we show how the different dimensions of financialisation affect social and economic outcomes related to inequalities as well as subjectivities relevant to public health.

The first dimension of financialisation is the financialisation of NFCs. The financial liberalisation of the post‐1980s period has induced NFCs either to finance real investment through private credit or rely heavily on market finance and external shareholders. Therefore, corporate debt ratios have increased significantly mainly to fund share repurchases to boost dividend payment under the pressure of shareholders. Most firms decrease other costs – mainly wages – to counterbalance the increases in overhead financial costs (Lazonick & O'Sullivan, 2000; Lin & Tomaskovic‐Devey, 2013).

The second dimension of financialisation is the financialisation of real estate. Since the early 1980s, financial institutions have shifted their focus on financing assets and especially real estate (Aalbers et al., 2020). Consequently, many countries have experienced mortgage debt‐fuelled real estate bubbles and major affordability crises, since private debt has financed purchasing existing real estate rather than building new (Kohl, 2020). Signing a household debt agreement entails a commitment to repay the debt plus interest within a predefined term. Consequently, over this period, individuals prioritise maintaining their employment to secure a steady flow of income rather than be more demanding in their negotiations over wages and working conditions. As reported by Sweet (2018), neoliberal narratives have reinforced the new subjectivity of indebtedness being associated with personal failure and risk averseness. Hence, the fear of private debt default has been identified as a key driver of wage reductions and declining labour militancy (Gouzoulis, 2020; Lazzarato, 2012).

Beyond mortgage debt, consumer debt is a third key dimension of financialisation, especially in advanced economies. Yet, since consumer debt is typically a very small proportion of total household debt (given that real estate is one of the most expensive purchases), its impact on the behaviour of indebted households will likely be less prominent.

Further, the fourth dimension of financialisation is the privatisation and financialisation of pension funds. The growing age of the population and several other factors have created concerns about the viability of pension funds over the last decades. One of the main responses to this potential crisis has been a notable change in the public and private pension mix, with pension funds investing in risky financial instruments (Ebbinghaus, 2011). Yet, the impact of this development on the behaviour of those effects has not been studied. Given the uncertainty that comes with pension funds investing in risky assets, one possible implication is that employees close to retirement will delay their retirement and retirees might have incentives to return to work to counterbalance a potential or expected loss of income.

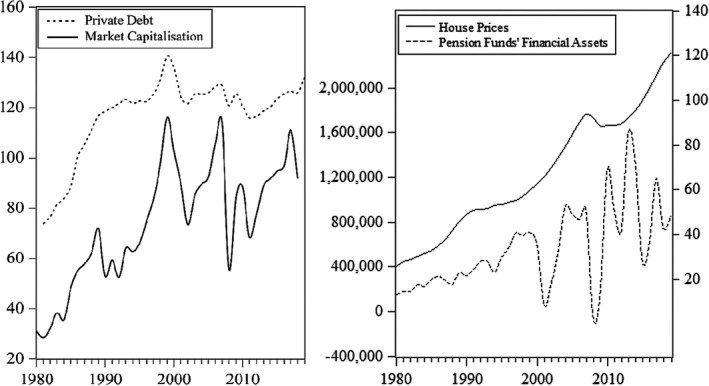

Figure 1 presents key global trends of financialisation, using measures related to the discussion above. The trends demonstrate a steep increase in all four indicators since 1980, highlighting the extent of this structural shift.1

FIGURE 1.

Global trends of financialisation. Sources & Definitions: Private Debt to the Non‐Financial Sector (% GDP; World), Market Capitalisation (% GDP; World) – World Bank; House Prices (Index [2015 = 100]; Right Axis; OECD average) – OECD; Pension Funds' Financial Assets (Total, Level; Left Axis; Annual Change, Million USD) – FRED

All things considered, there is evidence that financialisation has contributed to rising income inequalities through different channels. Given that rising inequality worsens health (Pickett & Wilson, 2015; Subramanian & Kawachi, 2004), redistributive policies can improve public health and wellbeing. Therefore, the financialisation–inequality–public health link leads to the broad question of whether ‘de‐financialisation’ policies are likely to ameliorate public health. Understanding better this nexus requires a more nuanced understanding of how financialisation not only affects income inequalities but also working and living conditions, as well as social behaviour and risk perception.

FINANCIALISATION, TRANSMISSIBLE DISEASES AND PUBLIC HEALTH – TOWARDS A NEW AGENDA

Despite the world has experienced various outbreaks of transmissible diseases over the last century, the COVID‐19 pandemic is the most significant public health crisis since the 1918 influenza. Contrary to SARS and MERS, the first COVID‐19 vaccines have already been developed, but their roll‐out remains slow with significant inequalities in their distribution, especially between the Global North and South. Thus, contagion dynamics and public health outcomes still depend crucially on the possibilities of non‐pharmaceutical interventions, such as physical distancing. These, in turn, depend on social and economic conditions that are influenced by financialisation. This leads to several questions related to a country's ability to implement physical distancing measures and individuals' ability to comply. Following this intuition, the question that arises is to what extend financialisation affects physical distancing decisions and abilities across the society? If this is the case, are contagious diseases more likely to spread easier and more difficult to make the public adhere to social distancing rules in more financialised societies? Below, we highlight three key channels through which financialisation can affect social conditions related to social distancing and underline a set of open questions that emerge for public health sociologists:

First, does the mortgage debt‐fuelled real estate affordability crisis lead firms and households to rent/purchase smaller workplaces and residencies? Since smaller places limit the possibilities of social distancing, do regions and cities that face such real estate crises also experience disease outbreaks that are more severe and occur more often? Regarding households, how does the rise of house/flat sharing as a form of renting affect contagious disease outbreaks, given that people who work in different workplaces live in multiple occupation properties with a common kitchen and/or bathroom? Does the fact that residencies in city centres have become unaffordable lead people to live the outskirts, thus, commute via crowded public transport that allows easier transmission of diseases? While there is a well‐established literature on the housing‐health nexus (Shaw, 2004; Swope & Hernández, 2019), our questions link more explicitly worsening housing conditions to the financialisation of the real estate, thus the improvement of public health to financial regulation. Utilising survey data that include information on housing conditions can offer interesting cross‐regional insights into the casual relationships described above.

Second, are the effects of the fear of private debt default only limited to wage reductions or they also induce people to do extra temporary/part‐time jobs while they are indebted to cover their increased financial commitments? If that is the case, how much does the fact that different people having contact with different workplaces during the day contributes to the spread of infectious diseases? Further, there is evidence that the emerging neoliberal subjectivity around private indebtedness leads to poorer subjective health behaviour and assessments as well as to stress‐related mental and physical health issues (Sweet, 2018; Turunen & Hiilamo, 2014). Accordingly, do indebted employees value income more than their health and return to work while public health conditions are not appropriate yet? Given the behavioural nature of these arguments, survey data analysis and semi‐structured interviews have the potential to provide fruitful insights regarding behavioural interventions.

Third, given the increased financial insecurity for older people due to pension funds' investments in risky financial assets, do we observe more people delaying their retirement or returning to work due to actual or expected loss of income as a consequence of these investments? If yes, and given that people over 60 years old are more vulnerable, do we observe more severe infectious disease outbreaks in societies whose pension funds are more financialised? Given that such data on employment dynamics are available for several economies (e.g. see OECD), time series and panel regression analysis would be an appropriate approach to assess this causal link.

In closing, while the study of financialisation and its social and economic implications has been a research focus across social sciences, it has been studied less in the fields focusing on the social aspects of public health. We believe that the broad questions outlined above underline links between financialisation and public health via the transformation of working, living and social conditions. Therefore, they set the research agenda for a new strand within the sociology of public health and illnesses that has the potential to offer critical policy insights. The answers to these questions would vary across countries and would be also influenced by other social, cultural and economic factors; hence, this question is the starting point for a variety of more specific questions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Giorgos Gouzoulis: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Giorgos Galanis: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Antonio Andreoni, Adam Hanieh, Stefanos Ioannou and participants of the Open University Business School's History and Political Economy of Business and Finance (HYPE) webinar series for their valuable feedback on earlier versions. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that substantially improved the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Gouzoulis, G., & Galanis, G. The impact of financialisation on public health in times of COVID‐19 and beyond. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2021;43:1328–1334. 10.1111/1467-9566.13305

Funding information

We have not received any funding for this work.

Additional COVID19‐related content is available online at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)1467-9566.covid-19-content

ENDNOTE

Pension funds' financial assets series are reported only for the US due to data availability.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study are openly available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FS.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS; https://data.oecd.org/price/housing‐prices.htm; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL594090005Q.

REFERENCES

- Aalbers, M. B., Fernandez, R., & Wijburg, G. (2020). The financialization of real estate. In Mader P., Mertens D., & van der Zwan N. (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of financialization (pp. 200–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, S., Pierides, D., Brisley, A., Weisshaar, C., & Blakeman, T. (2019). Financialising acute kidney injury: From the practices of care to the numbers of improvement. Sociology of Health and Illness, 41(5), 882–899. 10.1111/1467-9566.12868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, B. G., & Kim, J. C. (2011). The sociology of finance. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 239–259. 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, G. F., & Kim, S. (2015). Financialization of the economy. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 203–221. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, R. E. (2018). Credit, debt, and inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 237–261. 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus, B. (Ed.) (2011). The varieties of pension governance. OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, G. A. (2005). Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Galanis, G., & Hanieh, A. (2021). Incorporating social determinants of health into modelling of COVID‐19 and other infectious diseases: A baseline socio‐economic compartmental model. Social Science & Medicine, 274, 113794. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzoulis, G. (2020). Finance, discipline, and the labour share in the long‐run: France (1911–2010) and Sweden (1891–2000). British Journal of Industrial Relations. 10.1111/bjir.12576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, B. M., & Murray, S. F. (2019). Deconstructing the financialization of healthcare. Development and Change, 50(5), 1263–1287. 10.1111/dech.12517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keister, L. A. (2002). Financial markets, money, and banking. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 39–61. 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.140836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, S. (2020). Too much mortgage debt? The effect of housing financialization on housing supply and residential capital formation. Socio‐Economic Review. 10.1093/ser/mwaa030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio‐Economic Review, 3, 173–208. 10.1093/SER/mwi008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazonick, W., & O'Sullivan, M. (2000). Maximizing shareholder value, a new ideology for corporate governance. Economy and Society, 29(1), 13–35. 10.1080/030851400360541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarato, M. (2012). The making of the indebted man. Semiotext(e). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K. H., & Tomaskovic‐Devey, D. (2013). Financialization and US income inequality, 1970–2008. American Journal of Sociology, 118(5), 1284–1329. 10.1086/669499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, S., Begkos, C., Ellwood, S., & Mellingwood, C. (2020). Public value and pricing in English hospitals: Value creation or value extraction? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 102247. 10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. A., & Taylor, S. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. (2002). Financialization of daily life. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, V. (2007). Neoliberalism, globalization, and inequalities: Consequences for health and quality of life. Baywood Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Orhangazi, Ö. (2008). Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non‐financial corporate sector: A theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973–2003. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(6), 863–886. 10.1093/cje/ben009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, K. E., & Wilson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R., & Stephenson, N. (2016). Speculating on health: Public health meets finance in ‘health impact bonds’. Sociology of Health and Illness, 38, 1203–1216. 10.1111/1467-9566.12450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrecker, T. (2016). Neoliberalism and health: The linkages and the dangers. Sociology Compass, 10, 952–971. 10.1111/soc4.12408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 397–418. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparke, M. (2017). Austerity and the embodiment of neoliberalism as ill‐health: Towards a theory of biological sub‐citizenship. Social Science and Medicine, 187, 287–295. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, F., & Sridhar, D. (2018). The financialisation of global health. Wellcome Open Research, 3, 17. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.13885.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhammer, E. (2017). Determinants of the wage share: A panel analysis of advanced and developing economies. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 55, 3–33. 10.1111/bjir.12165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S. V., & Kawachi, I. (2004). Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiologic Review, 26(1), 78–91. 10.1093/epirev/mxh003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, E. (2018). “Like you failed at life”: Debt, health and neoliberal subjectivity. Social Science & Medicine, 212, 86–93. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swope, C. B., & Hernández, D. (2019). Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 243, 112571. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, E., & Hiilamo, H. (2014). Health effects of indebtedness: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwan, N. (2014). Making sense of financialization. Socio‐Economic Review, 12, 99–129. 10.1093/ser/mwt020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volscho, T. W., & Kelly, N. J. (2012). The rise of the superrich: Power resources, taxes, financial markets, and the dynamics of the top 1 percent, 1949 to 2008. American Sociological Review, 77(5), 679–699. 10.1177/0003122412458508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vural, I. (2017). Financialisation in health care: An analysis of private equity fund investments in Turkey. Social Science & Medicine, 187, 276–286. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz, R. (2001). The Sociology of health, illness and healthcare (2nd ed.). Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are openly available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FS.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS; https://data.oecd.org/price/housing‐prices.htm; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL594090005Q.