Abstract

Background:

There remains a lack of awareness around the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) procedural criteria for brain death and the surrounding controversies, leading to significant practice variability. This survey study assessed for existing knowledge and attitude among healthcare professionals regarding procedural criteria and potential change after an educational intervention.

Methods:

Healthcare professionals with increased exposure to brain injury at Mayo Clinic hospitals in Arizona and Florida were invited to complete an online survey consisting of 2 iterations of a 14-item questionnaire, taken before and after a 30-minute video educational intervention. The questionnaire gathered participants’ opinion of (1) their knowledge of the AAN procedural criteria, (2) whether these criteria determine complete, irreversible cessation of brain function, and (3) on what concept of death they base the equivalence of brain death to biological death.

Results:

Of the 928 people contacted, a total of 118 and 62 participants completed the pre-intervention and post-intervention questionnaire, respectively. The results show broad, unchanging support for the concept of brain death (86.8%) and that current criteria constitute best practice. While 64.9% agree further that the loss of consciousness and spontaneous breathing is sufficient for death, contradictorily, 37.6% believe the loss of additional integrated bodily functions such as fighting infection is necessary for death. A plurality trusts these criteria to demonstrate loss of brain function that is irreversible (67.6%) and complete (43.6%) at baseline, but there is significantly less agreement on both at post-intervention.

Conclusion:

Although there is consistent support that AAN procedural criteria are best for clinical practice, results show a tenuous belief that these criteria determine irreversible and complete loss of all brain function. Despite support for the concept of brain death first developed by the President’s Council, participants demonstrate confusion over whether the loss of consciousness and spontaneous breath are truly sufficient for death.

Keywords: American Academy of Neurology, brain death, coma depassé, irreversible coma, practice guidelines, World Brain Death Project

Introduction

The notion of brain death was first introduced by 2 French neurologists, Mollaret and Goulon, in 1959,1 but they did not equate this to the death of the whole person. Death of the whole person by neurologic criteria, was first introduced into the medical community in the United States by the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death in 1968 and written into law in the 1981 Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA).2,3 The UDDA defines that a person can be declared dead either by meeting the neurologic criteria or traditional cardiopulmonary death, and this definition has since been adopted by every state in the United States and many jurisdictions throughout the world.4,5 The 2010 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) procedural criteria in brain death determination presumably is the accepted medical standard for determining death by neurologic criteria in the United States, which is a revised elaboration of the same main steps originally provided in the Harvard ad-hoc committee report: essential preconditions, irreversible coma demonstrated by behavioral unresponsiveness, absent brainstem (pupillary, corneal, vestibule-ocular, ocular-cephalic, motor response to pain stimuli of sensory trigeminal nerve, gag, and cough) reflexes, and loss of spontaneous drive to breathe.6,7

There has been controversy around the issue of brain death being equivalent with biological death since its inception, but it has garnered new attention following the high-profile case of Jahi McMath, whose family chose not to accept the notion of death by neurologic criteria.8 Ethical concerns around the notion of brain death predated this case, however, and were addressed in a President’s Council on Bioethics in 2008. The Council provided a new philosophical rationale for death by neurologic criteria,9 whereby consciousness and spontaneous breath compose the fundamental vital works of a human being and the cessation of these activities define death, however significant disagreement with this rationale continues among bioethicists.10–14 Even if the notion of brain death according to this rationale of death by neurologic criteria were accepted, recent neuroscientific findings have raised the question whether the current AAN procedural criteria satisfactorily determine brain death as defined by the UDDA.15 This related but separate, scientific matter of whether these procedural criteria are valid was the subject of a 2015 Nevada Supreme Court case.16,17 The scientific and ethical controversies around the AAN procedural criteria for brain death determination continues to the present, as marked by Lewis et al recent call for the Uniform Law Commission to revise the UDDA.18 Advocates propose a firmer commitment to the current version of the AAN procedural criteria, including revising UDDA to align with the AAN criteria,18 disallowing objection to brain death protocol,19 and encouraging adoption of the AAN criteria around the world.20 On the other hand, critics urge caution and reconsideration of the current criteria and its underlying rationale, since erroneous declaration of death in medical practice has catastrophic consequences on patients and families.21,22

This academic controversy is reflected in clinical practice. It is relatively common for neurologists to encounter families who object to discontinuation of organ support after brain death23 and yet survey studies have shown that neurologists do not have a consistent rationale for accepting brain death as death, nor a clear understanding of diagnostic tests for brain death.23–26 This inconsistent understanding of the ethical and scientific basis of brain death begins to explain the wide variability seen in how brain death protocol is performed around the country.27 Similar studies demonstrate a lack of consensus in attitude and protocol outside the US as well28–31

There have been studies that assess for knowledge and attitudes about brain death among healthcare trainees in the United States and abroad.32,33 There have been efforts to assess improvement in knowledge regarding brain death following an educational intervention focused on the criteria themselves.34,35 There has not, however, been an effort to assess for both knowledge and attitude regarding brain death at baseline, and then also the potential for change upon receiving an educational intervention. Our project assessed initial level of awareness and attitudes toward brain death criteria across multiple types of healthcare professionals, which were then reassessed after showing a video presentation that reviewed (1) the criteria themselves and (2) details of both the neuroscientific and ethical debate surrounding the criteria. The purpose was to stimulate dialogue that ultimately brings our hospital system and others closer toward a wider and more informed agreement on either revision or adherence to the current brain death protocol per AAN.

Methods

Survey Creation

A 14-item questionnaire assessing knowledge and attitudes toward the notion of brain death and the AAN procedural criteria for determining brain death was developed for the purposes of this study (Online Supplemental Methods), with consultation from similar surveys in previous literature.24–26 Participants answered categorically from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree with the option to Choose Not to Answer. Specifically, the questionnaire items were designed to evaluate participants’ perception of the following:

the depth of their own knowledge of the current AAN criteria (#2, 3, 4)

whether the AAN criteria successfully determine irreversible loss of all brain functions (#5,6)

which physiologic functions are necessarily lost in death, that is, concept of death (#7, 8, 9)

whether the AAN criteria constitute best possible clinical practice (#11, 12)

whether patients might object to declaration of brain death by the AAN criteria (#10)

whether to relax the dead donor rule (#13)

whether more education and discussion around the topic of brain death is necessary (#1, 14)

Educational Intervention

This questionnaire was given to participants both before and after an educational intervention in the form of an online video presentation titled “A Framework for Revisiting Brain Death” (Online Supplemental Methods). This video presentation was curated and reviewed for the purposes of this study, and meant to accord with the questionnaire items. Specifically, the 30-minute video with accompanying transcript reviews the AAN criteria for determining brain death, distinguishes coma from other disorders of consciousness, gives a brief history on the topic of brain death, outlines the most salient scientific and then philosophical challenges to the AAN criteria, and concludes with a discussion reconciling these challenges with the realities of managing severe neurologic injury.

Survey Distribution

Participation in this study occurred entirely on a survey form hosted on the Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) software program, with a link to the survey emailed individually to participants.36 This survey form began on a page asking for 2 demographic identifiers (affiliated department and level of training), followed by the first iteration of the 14 item questionnaire. Participants were then instructed to access the video presentation by following a link to the host website of “Prezi,” a presentation platform (Online Supplemental Methods). A transcript of the presentation was made available to guide the viewing and future study (Online Supplemental Methods). Lastly, participants were asked to complete a second iteration of the identical 14-item questionnaire. Participants were advised that their participation will take around 40 minutes, should be completed in one sitting but can be interrupted and resumed, and that there is no compensation.

Participant Recruitment

A total of 578 participants were recruited at Mayo Clinic Arizona and 350 were recruited at Mayo Clinic Florida. At both sites, participants were recruited from departments with increased exposure to severely neurologically injured patients, specifically: Anesthesiology, Critical Care, Hospital Internal Medicine, Neurology, Neurosurgery, Transplant Surgery, and Palliative Medicine. An effort was made to recruit several types of health professions across these departments, including medical doctors and trainees (physicians, fellows, residents, medical students), advanced practitioners (nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants), as well as Respiratory Therapists. Recruitment emails were sent out between December 2019 and April 2020, with 3 reminder emails sent in that period. In-person solicitation was done in December 2019 at departmental meetings at Mayo Clinic Arizona.

Data Analysis

Pre-intervention questionnaire results were analyzed in total and in groups according to training type. Responses were further simplified by grouping regardless of the degree of agreement or disagreement. Fisher’s exact p-values < 0.05 were used to determine significant dissociation in response between training types. Participants who completed both iterations of the questionnaire were selected and their change in responses, including change in degree of agreement, were compiled. Sign rank test was used to calculate significance in change for all participants irrespective of training type for each questionnaire item. All hypotheses were 2-sided with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics

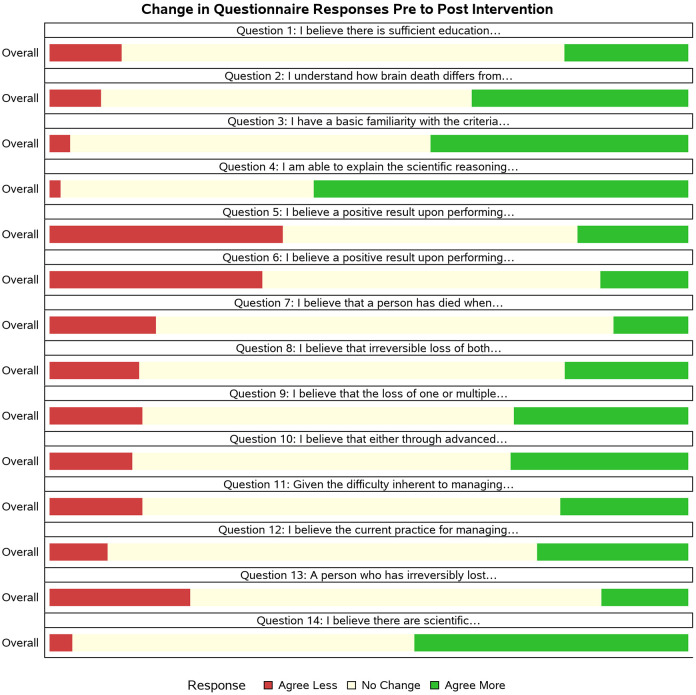

Of the 928 people contacted, 118 (13%) chose to participate and completed the pre-intervention questionnaire (see Table 1). The preintervention responses to the survey questionnaire for all participants and grouped by training type are displayed in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The change in responses to the survey questionnaire after the educational intervention for all participants and grouped by training type are displayed in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Detailed responses to the survey questionnaires are reported before and after the educational intervention for all participants (Table 2) and pre-intervention by training type (Table 3) and the changes in responses by training type (Table 4). The 2 most represented groups were respiratory therapists (N = 37) and nurses/nurse practitioners in the critical care department (N = 42). The latter accounted for all of the Critical Care department respondents except for 1 critical care physician. Due to the wider participation between these 2 groups, data was regrouped more broadly on the basis of type of training rather than smaller categories of department or level of training. Participants were therefore grouped into 3 training type categories: “Medical Doctor” referring to physicians, fellows, residents, and medical students with completed or eventual MD degree, “Advanced Practice” referring to nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, and “Respiratory Therapists.” The majority of respondents in the “Medical Doctor” training type were physicians (N = 25). The most represented specialty department for medical doctors was Hospital Internal Medicine (N = 10) followed by Neurology (N = 7).

Table 1.

Demographics of All Participants on Basis of Affiliated Department and Type/Level of Training.

| N = 118 | |

|---|---|

| Department, n (%) | |

| Anesthesiology | 5 (4.4%) |

| Hospital Internal Medicine | 10 (8.8%) |

| Critical Care | 43 (38.1%) |

| Neurology | 7 (6.2%) |

| Neurosurgery | 1 (0.9%) |

| Respiratory Support | 37 (32.7%) |

| Other | 3 (2.7%) |

| Palliative Care | 2 (1.8%) |

| Transplant Surgery | 5 (4.4%) |

| Level, n (%) | |

| Medical Student | 5 (4.2%) |

| Resident | 7 (5.9%) |

| Fellow | 1 (0.8%) |

| Physician | 25 (21.2%) |

| Physician Assistant | 1 (0.8%) |

| Nurse or Nurse Practitioner | 42 (35.6%) |

| Respiratory Therapist | 37 (31.4%) |

Figure 1.

Pre-interview questionnaire responses overall.

Figure 2.

Pre-intervention responses displayed by training type.

Figure 3.

Overall change in response from pre-intervention to post-intervention questionnaire.

Figure 4.

Change in response from pre-intervention to post-intervention questionnaire by training type.

Table 2.

Overall Responses on Brain Death Survey Before and After the Educational Intervention.

| Pre-intervention, N = 118 | Pre-intervention completed, N = 62 | Post-intervention, N = 62 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I believe there is sufficient education regarding brain death in U.S. medical training | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 8 (7.1%) | 5 (8.1%) | 5 (8.1%) |

| Disagree | 60 (53.1%) | 37 (59.7%) | 27 (43.5%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 21 (18.6%) | 10 (16.1%) | 7 (11.3%) |

| Agree | 19 (16.8%) | 8 (12.9%) | 18 (29.0%) |

| Strongly Agree | 5 (4.4%) | 2 (3.2%) | 5 (8.1%) |

| 2. I understand how brain death differs from other neurologically impaired states including minimally conscious state, persistent vegetative state, and coma | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 25 (21.4%) | 11 (17.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 11 (9.4%) | 7 (11.3%) | 8 (12.9%) |

| Agree | 52 (44.4%) | 29 (46.8%) | 33 (53.2%) |

| Strongly Agree | 28 (23.9%) | 15 (24.2%) | 21 (33.9%) |

| 3. I have a basic familiarity with the criteria stated in the AAN protocol for deeming a patient to be brain dead | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 6 (5.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 22 (18.6%) | 10 (16.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 11 (9.3%) | 9 (14.5%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| Agree | 63 (53.4%) | 33 (53.2%) | 39 (62.9%) |

| Strongly Agree | 16 (13.6%) | 8 (12.9%) | 20 (32.3%) |

| 4. I am able to explain the scientific reasoning that supports the criteria stated in the AAN protocol | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 10 (8.8%) | 3 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 51 (44.7%) | 27 (45.0%) | 3 (5.0%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 25 (21.9%) | 16 (26.7%) | 11 (18.3%) |

| Agree | 21 (18.4%) | 10 (16.7%) | 35 (58.3%) |

| Strongly Agree | 7 (6.1%) | 4 (6.7%) | 11 (18.3%) |

| 5. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates irreversible loss of brain function | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Disagree | 5 (4.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | 9 (15.5%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 27 (25.7%) | 12 (22.6%) | 15 (25.9%) |

| Agree | 51 (48.6%) | 27 (50.9%) | 22 (37.9%) |

| Strongly Agree | 20 (19.0%) | 11 (20.8%) | 11 (19.0%) |

| 6. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates loss of all functions of the entire brain | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 4 (4.0%) | 2 (3.9%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| Disagree | 23 (22.8%) | 14 (27.5%) | 28 (46.7%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 30 (29.7%) | 14 (27.5%) | 11 (18.3%) |

| Agree | 30 (29.7%) | 16 (31.4%) | 11 (18.3%) |

| Strongly Agree | 14 (13.9%) | 5 (9.8%) | 6 (10.0%) |

| 7. I believe that a person has died when there is irreversible loss of function of the entire brain including brainstem | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.6%) |

| Disagree | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (8.3%) | 7 (11.3%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 8 (7.0%) | 3 (5.0%) | 5 (8.1%) |

| Agree | 56 (49.1%) | 29 (48.3%) | 28 (45.2%) |

| Strongly Agree | 43 (37.7%) | 22 (36.7%) | 21 (33.9%) |

| 8. I believe that irreversible loss of both consciousness and internal drive to breathe without machine are together sufficient to declare death | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 6 (5.3%) | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Disagree | 22 (19.3%) | 13 (22.0%) | 10 (16.7%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 12 (10.5%) | 5 (8.5%) | 7 (11.7%) |

| Agree | 48 (42.1%) | 25 (42.4%) | 27 (45.0%) |

| Strongly Agree | 26 (22.8%) | 14 (23.7%) | 15 (25.0%) |

| 9. I believe that the loss of one or multiple of the following bodily functions is necessary to declare death: autonomic responses in heart rate, maintenance of fluid balance, stable body temperature, healing wounds, fighting infections | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 6 (5.5%) | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Disagree | 36 (33.0%) | 19 (34.5%) | 23 (39.0%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 26 (23.9%) | 12 (21.8%) | 11 (18.6%) |

| Agree | 34 (31.2%) | 19 (34.5%) | 18 (30.5%) |

| Strongly Agree | 7 (6.4%) | 2 (3.6%) | 6 (10.2%) |

| 10. I believe that either through advanced directive or medical power of attorney, patients should be allowed to decline having the AAN protocol performed (i.e. that patients should be allowed to reject the concept of brain death) | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 14 (13.1%) | 6 (10.7%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Disagree | 36 (33.6%) | 19 (33.9%) | 17 (29.8%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 24 (22.4%) | 12 (21.4%) | 9 (15.8%) |

| Agree | 25 (23.4%) | 16 (28.6%) | 18 (31.6%) |

| Strongly Agree | 8 (7.5%) | 3 (5.4%) | 6 (10.5%) |

| 11. Given the difficulty inherent to managing severe neurologic injury, I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcome for the patient | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Disagree | 8 (7.5%) | 2 (3.6%) | 5 (8.5%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 41 (38.3%) | 23 (41.1%) | 19 (32.2%) |

| Agree | 41 (38.3%) | 22 (39.3%) | 23 (39.0%) |

| Strongly Agree | 16 (15.0%) | 8 (14.3%) | 11 (18.6%) |

| 12. I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcomes for the patient’s loved ones, care providers, and the healthcare system at large | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disagree | 17 (15.2%) | 9 (15.3%) | 5 (8.9%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 36 (32.1%) | 17 (28.8%) | 19 (33.9%) |

| Agree | 41 (36.6%) | 23 (39.0%) | 21 (37.5%) |

| Strongly Agree | 18 (16.1%) | 10 (16.9%) | 11 (19.6%) |

| 13. A person who has irreversibly lost consciousness, but continues other bodily functions, should be eligible for organ donation | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 6 (5.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (6.6%) |

| Disagree | 10 (8.9%) | 6 (10.0%) | 7 (11.5%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 16 (14.3%) | 10 (16.7%) | 12 (19.7%) |

| Agree | 51 (45.5%) | 25 (41.7%) | 22 (36.1%) |

| Strongly Agree | 29 (25.9%) | 17 (28.3%) | 16 (26.2%) |

| 14. I believe there are scientific and/or ethical issues surrounding the current AAN brain death determination protocol that should be further examined | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 7 (6.6%) | 3 (5.2%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Disagree | 18 (17.0%) | 7 (12.1%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 33 (31.1%) | 19 (32.8%) | 15 (25.0%) |

| Agree | 33 (31.1%) | 23 (39.7%) | 31 (51.7%) |

| Strongly Agree | 15 (14.2%) | 6 (10.3%) | 11 (18.3%) |

First column for all responses to the first survey regardless of completion status, second column are for results of the first survey only among those who completed the second survey, and third column is the second survey results.

Table 3.

Pre-Intervention Questionnaire Results in Total and by Training Type With Agreement Levels Grouped.

| Training type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (physician, fellow, resident, and medical student) (N = 38) | Advanced practice (nurse, nurse practitioner, and

physician’s assistant) (N = 43) |

Respiratory therapist (N = 37) | Total (N = 118) | P-value | |

| 1. I believe there is sufficient education regarding brain death in U.S. medical training. | 0.00261 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 23 (60.5%) | 30 (75.0%) | 15 (42.9%) | 68 (60.2%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 5 (13.2%) | 2 (5.0%) | 14 (40.0%) | 21 (18.6%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 10 (26.3%) | 8 (20.0%) | 6 (17.1%) | 24 (21.2%) | |

| 2. I understand how brain death differs from other neurologically impaired states including minimally conscious state, persistent vegetative state, and coma | 0.01511 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 6 (15.8%) | 10 (23.3%) | 10 (27.8%) | 26 (22.2%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 8 (22.2%) | 11 (9.4%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 30 (78.9%) | 32 (74.4%) | 18 (50.0%) | 80 (68.4%) | |

| 3. I have a basic familiarity with the criteria stated in the AAN protocol for deeming a patient to be brain dead | 0.15971 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 4 (10.5%) | 13 (30.2%) | 11 (29.7%) | 28 (23.7%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 3 (7.9%) | 4 (9.3%) | 4 (10.8%) | 11 (9.3%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 31 (81.6%) | 26 (60.5%) | 22 (59.5%) | 79 (66.9%) | |

| 4. I am able to explain the scientific reasoning that supports the criteria stated in the AAN protocol | 0.00221 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 16 (42.1%) | 28 (68.3%) | 17 (48.6%) | 61 (53.5%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 6 (15.8%) | 5 (12.2%) | 14 (40.0%) | 25 (21.9%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 16 (42.1%) | 8 (19.5%) | 4 (11.4%) | 28 (24.6%) | |

| 5. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates irreversible loss of brain function | 0.28161 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 2 (5.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 2 (6.1%) | 7 (6.7%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 7 (18.4%) | 7 (20.6%) | 13 (39.4%) | 27 (25.7%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 29 (76.3%) | 24 (70.6%) | 18 (54.5%) | 71 (67.6%) | |

| 6. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates loss of all functions of the entire brain | 0.12891 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 15 (40.5%) | 7 (21.9%) | 5 (15.6%) | 27 (26.7%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 9 (24.3%) | 8 (25.0%) | 13 (40.6%) | 30 (29.7%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 13 (35.1%) | 17 (53.1%) | 14 (43.8%) | 44 (43.6%) | |

| 7. I believe that a person has died when there is irreversible loss of function of the entire brain including brainstem | 0.37671 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 4 (10.8%) | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (5.7%) | 7 (6.1%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 1 (2.7%) | 3 (7.1%) | 4 (11.4%) | 8 (7.0%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 32 (86.5%) | 38 (90.5%) | 29 (82.9%) | 99 (86.8%) | |

| 8. I believe that irreversible loss of both consciousness and internal drive to breathe without machine are together sufficient to declare death | 0.13921 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 13 (34.2%) | 8 (19.0%) | 7 (20.6%) | 28 (24.6%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 2 (5.3%) | 3 (7.1%) | 7 (20.6%) | 12 (10.5%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 23 (60.5%) | 31 (73.8%) | 20 (58.8%) | 74 (64.9%) | |

| 9. I believe that the loss of one or multiple of the following bodily functions is necessary to declare death: autonomic responses in heart rate, maintenance of fluid balance, stable body temperature, healing wounds, fighting infections | 0.00041 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 22 (61.1%) | 15 (36.6%) | 5 (15.6%) | 42 (38.5%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 8 (22.2%) | 6 (14.6%) | 12 (37.5%) | 26 (23.9%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 6 (16.7%) | 20 (48.8%) | 15 (46.9%) | 41 (37.6%) | |

| 10. I believe that either through advanced directive or medical power of attorney, patients should be allowed to decline having the AAN protocol performed (i.e. that patients should be allowed to reject the concept of brain death) | 0.03061 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 23 (60.5%) | 19 (51.4%) | 8 (25.0%) | 50 (46.7%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 6 (15.8%) | 6 (16.2%) | 12 (37.5%) | 24 (22.4%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 9 (23.7%) | 12 (32.4%) | 12 (37.5%) | 33 (30.8%) | |

| 11. Given the difficulty inherent to managing severe neurologic injury, I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcome for the patient | 0.17111 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (10.8%) | 5 (15.2%) | 9 (8.4%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 15 (40.5%) | 14 (37.8%) | 12 (36.4%) | 41 (38.3%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 22 (59.5%) | 19 (51.4%) | 16 (48.5%) | 57 (53.3%) | |

| 12. I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcomes for the patient s loved ones, care providers, and the healthcare system at large | 0.33251 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 5 (13.5%) | 8 (20.0%) | 4 (11.4%) | 17 (15.2%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 8 (21.6%) | 14 (35.0%) | 14 (40.0%) | 36 (32.1%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 24 (64.9%) | 18 (45.0%) | 17 (48.6%) | 59 (52.7%) | |

| 13. A person who has irreversibly lost consciousness, but continues other bodily functions, should be eligible for organ donation | 0.17381 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 3 (8.6%) | 5 (11.9%) | 8 (22.9%) | 16 (14.3%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 7 (20.0%) | 3 (7.1%) | 6 (17.1%) | 16 (14.3%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 25 (71.4%) | 34 (81.0%) | 21 (60.0%) | 80 (71.4%) | |

| 14. I believe there are scientific and/or ethical issues surrounding the current AAN brain death determination protocol that should be further examined | 0.83711 | ||||

| Disagree or Strongly Disagree | 9 (23.7%) | 10 (29.4%) | 6 (17.6%) | 25 (23.6%) | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 11 (28.9%) | 10 (29.4%) | 12 (35.3%) | 33 (31.1%) | |

| Agree or Strongly Agree | 18 (47.4%) | 14 (41.2%) | 16 (47.1%) | 48 (45.3%) | |

1Fisher Exact p-value for degree of dissociation between training types.

Table 4.

Change in Direction and Degree of Opinion Between Pre-Intervention and Post-Intervention Responses for Participants Who Completed Both Surveys.

| Total (N = 62) | Training type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (physician, fellow, resident, and medical student) (N = 25) |

Advanced practice (nurse, nurse practitioner,

and physician’s assistant) (N=15) |

Respiratory therapist (N = 22) | ||

| 1. I believe there is sufficient education regarding brain death in U.S. medical training | ||||

| Agree Less | 7 (11.3%) | 4 (16.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| No Change | 43 (69.4%) | 20 (80.0%) | 10 (66.7%) | 13 (59.1%) |

| Agree More | 12 (19.4%) | 1 (4.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| P= 0.2200 | ||||

| 2. I understand how brain death differs from other neurologically impaired states including minimally conscious state, persistent vegetative state, and coma | ||||

| Agree Less | 5 (8.1%) | 1 (4.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| No Change | 36 (58.1%) | 17 (68.0%) | 10 (66.7%) | 9 (40.9%) |

| Agree More | 21 (33.9%) | 7 (28.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 10 (45.5%) |

| P= 0.0002 | ||||

| 3. I have a basic familiarity with the criteria stated in the AAN protocol for deeming a patient to be brain dead | ||||

| Agree Less | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| No Change | 35 (56.5%) | 14 (56.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 13 (59.1%) |

| Agree More | 25 (40.3%) | 9 (36.0%) | 7 (46.7%) | 9 (40.9%) |

| P <0.0001 | ||||

| 4. I am able to explain the scientific reasoning that supports the criteria stated in the AAN protocol | ||||

| Missing | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Agree Less | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| No Change | 23 (39.7%) | 10 (40.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| Agree More | 34 (58.6%) | 15 (60.0%) | 9 (81.8%) | 10 (45.5%) |

| P <0.0001 | ||||

| 5. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates irreversible loss of brain function | ||||

| Missing | 10 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Agree Less | 19 (36.5%) | 10 (40.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| No Change | 24 (46.2%) | 11 (44.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 9 (47.4%) |

| Agree More | 9 (17.3%) | 4 (16.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| P = 0.0357 | ||||

| 6. I believe a positive result upon performing the AAN protocol demonstrates loss of all functions of the entire brain | ||||

| Missing | 11 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| Agree Less | 17 (33.3%) | 7 (28.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| No Change | 27 (52.9%) | 14 (56.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 10 (55.6%) |

| Agree More | 7 (13.7%) | 4 (16.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| P = 0.0184 | ||||

| 7. I believe that a person has died when there is irreversible loss of function of the entire brain including brainstem | ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Agree Less | 10 (16.7%) | 4 (16.0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (23.8%) |

| No Change | 43 (71.7%) | 16 (64.0%) | 12 (85.7%) | 15 (71.4%) |

| Agree More | 7 (11.7%) | 5 (20.0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| P = 0.3424 | ||||

| 8. I believe that irreversible loss of both consciousness and internal drive to breathe without machine are together sufficient to declare death | ||||

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Agree Less | 8 (14.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (14.3%) | 5 (25.0%) |

| No Change | 38 (66.7%) | 17 (73.9%) | 11 (78.6%) | 10 (50.0%) |

| Agree More | 11 (19.3%) | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (25.0%) |

| P = 0.3840 | ||||

| 9. I believe that the loss of one or multiple of the following bodily functions is necessary to declare death: autonomic responses in heart rate, maintenance of fluid balance, stable body temperature, healing wounds, fighting infections | ||||

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Agree Less | 8 (14.5%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| No Change | 32 (58.2%) | 14 (58.3%) | 8 (61.5%) | 10 (55.6%) |

| Agree More | 15 (27.3%) | 9 (37.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| P = 0.4823 | ||||

| 10. I believe that either through advanced directive or medical power of attorney, patients should be allowed to decline having the AAN protocol performed (i.e. that patients should be allowed to reject the concept of brain death) | ||||

| Missing | 8 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Agree Less | 7 (13.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| No Change | 32 (59.3%) | 16 (66.7%) | 5 (45.5%) | 11 (57.9%) |

| Agree More | 15 (27.8%) | 6 (25.0%) | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| P = 0.2053 | ||||

| 11. Given the difficulty inherent to managing severe neurologic injury, I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcome for the patient | ||||

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Agree Less | 8 (14.5%) | 2 (8.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | 4 (20.0%) |

| No Change | 36 (65.5%) | 18 (75.0%) | 5 (45.5%) | 13 (65.0%) |

| Agree More | 11 (20.0%) | 4 (16.7%) | 4 (36.4%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| P = 0.5722 | ||||

| 12. I believe the current practice for managing brain death ensures the best possible outcomes for the patient’s loved ones, care providers, and the healthcare system at large | ||||

| Missing | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Agree Less | 5 (9.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| No Change | 37 (67.3%) | 16 (69.6%) | 7 (58.3%) | 14 (70.0%) |

| Agree More | 13 (23.6%) | 6 (26.1%) | 3 (25.0%) | 4 (20.0%) |

| P = 0.2514 | ||||

| 13. A person who has irreversibly lost consciousness, but continues other bodily functions, should be eligible for organ donation | ||||

| Missing | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Agree Less | 13 (22.0%) | 6 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (33.3%) |

| No Change | 38 (64.4%) | 14 (58.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 12 (57.1%) |

| Agree More | 8 (13.6%) | 4 (16.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| P = 0.1611 | ||||

| 14. I believe there are scientific and/or ethical issues surrounding the current AAN brain death determination protocol that should be further examined | ||||

| Missing | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Agree Less | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| No Change | 30 (53.6%) | 13 (52.0%) | 7 (58.3%) | 10 (52.6%) |

| Agree More | 24 (42.9%) | 12 (48.0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 7 (36.8%) |

| P <0.0001 | ||||

Overall results shown on the left with Sign rank p-value boxed and italicized underneath to show significance of the change among participants overall. Change in opinion is then shown by training type to the right of the solid line.

Around half of these participants (N = 62) went on to complete the educational intervention and post-intervention questionnaire. A larger proportion of Advanced Practice respondents chose not to complete the study past the pre-intervention questionnaire than the remaining 2 training types. There were also multiple missing responses to several questionnaire items (up to 11 missing for question 6) at post-intervention.

i) Depth of knowledge of the AAN criteria

On questions regarding participants’ knowledge on the current AAN procedural criteria for determining brain death, at baseline most reported agreeing or strongly agreeing that they could distinguish brain death from other neurologically impaired states (Tables 2 and 3: 68.4%, Question 2) and that they had a basic familiarity with the AAN criteria (66.9%, Question 3), but far fewer endorsed being able to explain the scientific reasoning behind the criteria (24.6%, Question 4). When assessing by type of training, respiratory therapists were less likely to agree that they understand the difference between brain death and other impaired states of consciousness (Table 3: p = 0.0151) and MDs were more likely to report having an understanding of the scientific reasoning behind the criteria (p = 0.0022).

Notably, there was statistically significant improvement in participants’ knowledge on the AAN criteria for all 3 questions after the educational intervention, (Table 4: p-value = 0.0002, <0.0001, <0.0001 for Questions 2, 3, and 4, respectively), without there being an appreciable difference at baseline among those who completed the study in entirety.

ii) Scientific validity of the AAN criteria

Agreement over whether the AAN procedural criteria in fact demonstrate irreversible loss of brain function, and separately whether they in fact demonstrates loss of all functions of the entire brain were assessed in question 5 and 6, respectively. At baseline there was broad affirmative agreement for both questions overall, although notably there was less agreement that the AAN procedural criteria assess all brain functions (Tables 2 and 3: Question 5: 67.6% vs. Question 6: 43.6%). This rupture is widest for medical doctors (Table 3: Question 5: 76.3% vs. Question 6: 35.1%).

At post-intervention, there was statistically significant less agreement with both questions (Table 4: Question 5: p = 0.03571, Question 6: p = 0.0184) for participants overall. Notably however, these 2 questions did also have the highest number of missing responses at post-intervention (Question 5: 10, Question 6: 11). None of these missing responses were from MDs, and only 4 of 25 MDs responded with more agreement that the AAN procedural criteria satisfy the UDDA brain death definition for both questions 5 and 6.

iii) Concepts of death

Questions 7 through 9 assess participants’ beliefs around what constitutes the death of a human being, that is, which physiologic functions must cease for death to be declared. Results from Question 7 demonstrate overwhelming agreement with the notion of brain death itself, specifically that the death of the brain as defined by the UDDA indeed constitutes death of the entire human being (Tables 3 and 4: 86.8% agreement at baseline with no significant change at post-intervention). There was similarly wide agreement both before and after intervention with Question 8 (Table 2: pre: 64.9%, post: 70.0%), which asks whether the loss of 2 physiologic functions: consciousness and spontaneous breathing, are sufficient to declare death.

In a logically inconsistent pattern, there was relatively less agreement over whether the cessation of an additional integrated bodily function such as fighting infection is necessary to declare death, with participants divided almost evenly at baseline (Tables 2 and 3: 38.5% disagree and 37.6% agree with Question 9). Although again there was no change in opinion whether the loss of consciousness and spontaneous breathing is sufficient for death after the educational intervention, at post-intervention 15 participants agreed more that another bodily function is necessary while only 8 agreed less and 7 chose not to answer (Table 4).

On analysis by training type, at baseline MDs were significantly more likely to disagree that another function might be necessary compared to other training types (Table 3: p = 0.004), consistent with their broad agreement with Question 8. At post-intervention, many more medical doctors agreed, contradictorily, with both question 8 (Table 4: 5 agree more vs 1 agrees less) and question 9 (9 agree more vs. 1 agrees less).

iv) Best possible practice

Questions 11 and 12 gauge whether participants believe, given the difficulty inherent to managing severe neurologic injury, that the current practice ensures the best outcomes for the patient and separately for other parties involved (patient’s loved ones, care providers, the health system at large). The majority of respondents agreed that the current practice is best for all involved (Tables 2 and 3: 53.3%, 52.7%) with no significant differences between training types. After the educational intervention which discussed several scientific and philosophical objections to continuing the current practice, in fact a higher number of participants agreed more for questions 11 and 12, (Table 4: 11, 13) than agreed less (8, 5) that the current practice is best for both the patient and all other stakeholders. This change, however, is not statistically significant and 7 of 62 participants did not answer for both these questions.

v) Conscientious objection

Currently, only the state of New Jersey has a statute for allowing refusal to having the brain death protocol performed on the severely brain injured patient. Question 10 gauges opinion whether either through advanced directive or medical power of attorney patients may decline to having brain death protocol performed on them. At baseline, more participants disagreed with giving this option to patients (Tables 2 and 3: 46.7%) than those who agreed or were neutral. MDs were even more likely to disagree with allowing this option for patients than other training types (Table 3: p = 0.0306). After the educational intervention, a higher number of participants agreed more with giving patients this option than agreed less (Table 4: 15 vs 7) although this was not a statistically significant change and 8 participants chose not to answer.

vi) The dead donor rule

Question 13 assesses attitudes toward the dead donor rule, which mandates that patients are declared dead either by neurologic or cardiopulmonary criteria before they are eligible to become organ donors. A large majority (Tables 2 and 3: 71.4%) of participants believe that a person who has irreversibly lost consciousness but continues other bodily functions should be eligible for organ donation and thereby support relaxing the dead donor rule. This did not change after the educational intervention and there was no difference by training type.

vii) Further discussion

Together the first and last question of the survey gauge participants’ belief whether more education (Question 1) and critical discussion around the current practice (Question 14) is necessary. The majority of participants (60.9%) disagreed that there is sufficient education about brain death and this did not change after intervention (Tables 2, 3, 4). Those who disagreed are the most represented group across all training types but there was significant variation among training types (Table 3: p = 0.0026), as critical care nurses who compose the training type “Advanced Practice” were the most likely to disagree that there is sufficient education (75.0%). Those who agreed that there are scientific and ethical issues around the AAN criteria that need examination were the most represented group at baseline (Tables 2 and 3: 45.3%) and then at post-intervention there was a statistically significant increase in agreement (Table 4: p <0.0001).

Discussion

While not universally accepted,22,37,38 the notion of brain death, specifically the whole-brain concept of brain death given in the UDDA,39 is found to be broadly accepted by the participants in this study. In fact, the question (#7) gauging belief in the whole-brain concept of death is the most agreed-to item on the questionnaire with the least amount of change after the educational intervention. This baseline support for the notion of brain death is moreover held strongly enough that a plurality of participants disagree with allowing patients to conscientiously object to brain death determination protocol through advanced directive.

A similarly high degree of agreement is seen in Question 13, which asks whether those who have irreversibly lost consciousness should be eligible for organ donation, suggesting that participants may either want to relax the dead donor rule or they believe in an even narrower, higher-brain concept of brain death. Nair-Collins et al reported a similar attitude toward relaxing the dead donor rule for organ donation in irreversible coma among the general public.40 The practices of brain death declaration and organ donation arose together and remain interdependent, and it is unclear how strongly the need for viable organs strengthens belief in the notion of brain death or the concept of brain death as higher brain.4,41 Regardless, support behind a higher brain concept of death among neurologists has been shown in similar studies.24,25,26 Consistent with this emphasis on consciousness, participants in this study widely agree with the 2008 President Council conclusion that an irreversible loss of consciousness along with loss of an internal drive to breathe (without machine) are together sufficient for death (Question 8). As aforementioned, the Council identifies these 2 functions as the “fundamental vital works” of the human being, signaling his or her ability to engage with the world, although earlier studies have shown that few designate a lack of “vital work” as part of their concept of death that is met in brain death.24

Yet despite this wide agreement that the irreversible loss of consciousness and spontaneous breathing is together sufficient for death (and apparent support that the loss of consciousness alone may be sufficient), the results show a contradictory division in opinion at baseline as to whether the loss of an additional integrated bodily function such as fighting infection may be necessary for death. After an educational intervention that reviews both the President’s Council rationale for selecting these 2 functions as definitive of life as well as popular objections that other bodily functions continuing past the declaration of brain death exhibit evidence of somatic integration,10,11,12 the confusion grows only further as more participants agree to both questions 8 and 9. This increased confusion at post-intervention is seen even among medical doctors, who were at baseline the only training type to coherently agree with Question 8 while disagreeing with Question 9. Altogether these findings reveal an existing hesitation (which can be drawn out even for physicians) over whether the loss of at least 1 additional bodily function displaying somatic integration is necessary for death, which stands in contradiction with thorough support for the President’s Council decision that it is not necessary. This hesitation, identified by the Council itself as a serious objection to the current brain death protocol, should be taken into account amid current conversation around revising the UDDA to further align with the President’s Council conclusion.18,19,20

At present, however, the UDDA continues to define brain death as irreversible loss of all functions of the entire brain, and the 2010 AAN procedural criteria are being trusted to determine this. Whether these criteria in fact succeed in demonstrating whole-brain death per UDDA, or even true brainstem death, is a matter of scientific and legal debate.21 Although there is a definite lack of understanding for the scientific reasoning behind the AAN procedural criteria even on the part of MDs, at baseline there is a high degree of trust across training types that these criteria demonstrate loss of brain function that is irreversible. Even prior to the educational intervention that reviews scientific criticisms, there is remarkably less agreement, especially among MDs, that the AAN criteria determine complete loss of brain function. At baseline then, the prevailing opinion that the tested brain functions of consciousness and spontaneous breathing are lost irreversibly upon a positive result does indeed satisfy the concept of death articulated by the President’s Council, but there is more doubt over whether this further entails a complete loss of all brain function as the UDDA demands.

After the educational intervention wherein the potential for remaining viable brain tissue and brain function like hypothalamic-pituitary ADH secretion is reviewed, there is a statistically significant change in opinion on both questions. While the majority continues to agree that the AAN criteria determine irreversible loss, only about a quarter of respondents were left agreeing that the AAN criteria determine complete loss of brain function. Therefore, both aspects of the AAN procedural criteria’s satisfaction of the totality and irreversibility of ceased brain function stipulated in the UDDA have been questioned by recent neuroscientific findings, with a particular preexisting and illuminable doubt regarding its determination of complete loss of brain function. When taken alongside the hesitation over whether the loss of an additional integrated bodily function might be necessary to declare death, this perceived failure of the AAN procedural criteria to demonstrate complete loss of all brain function may urge some to question whether all essential functions of human life have been correctly deemed lost upon a positive result on the these criteria.

Although after the educational intervention confusion only increased around the definition of death underlying brain death, and although there was significantly less agreement that the AAN procedural criteria demonstrates irreversible, complete loss of brain function, at post-intervention there is actually even more agreement that the current practice is best clinical practice. While not a statistically significant change, it is telling that despite twice completing a questionnaire that by nature raises doubts around the current practice and engaging in a half-hour presentation of the issue replete with philosophical and scientific objections to the current practice, the majority of participants continue to agree that the current practice ensures the best possible outcomes for all involved. This speaks to the deeply understood clinical utility of the AAN procedural criteria and a resistance to adapting the standard of care in response to ethical and scientific objections. Any combination of reasons, mentioned and not mentioned, underlie this commitment to the current practice, including: the plausible albeit debatable belief of the brain as the exclusive locus of integration, the utility of brain death for organ procurement, and the frequently argued futility of continuation of care for severely neurologically injured patients.

Despite this widely-held and resilient belief in the current practice as best practice, however, after these considerations are discussed in the educational intervention, there is more openness toward letting patients make the decision of brain death declaration for themselves. This change, alongside broad agreement that more education and discussion around the issue is necessary, together reflect an acknowledgment that the current brain death criteria fail to unequivocally (with full scientific validity and philosophical unanimity) justify death of the human being.42 This is implied by the other discussed findings already, which show confusion around the concept of death honored in brain death, a lack of scientific understanding of the AAN procedural criteria even on the part of MDs, and marked disagreement that the AAN criteria satisfies the UDDA as they currently (and legally) purport to. Educational interventions similar to the one developed for the purposes of this study, disseminated across healthcare professions, may be crucial to generating a more informed agreement on this critical matter.

As an additional practical and procedural consideration, given the wide agreement on consciousness as a definitive feature of life necessarily lost in death and appreciable doubt both before and after the intervention as to whether the AAN procedural criteria determine irreversible loss of consciousness, it follows that further discussion is warranted around the amount of time being used to determine irreversible coma and whether organ procurement needs to take place with administration of full anesthesia.43,44 Since the real-life cases of Zack Dunlap45 and Jahi McMath46,47 illustrate that unresponsiveness does not ascertain the absence of consciousness, it follows that the AAN procedural criteria (even when applied correctly) do not necessarily exclude the capacity for conscious awareness or response to noxious stimuli. The prevalence of these false positive cases with continued conscious awareness is unknown, because patients are either surgically procured or have life support withdrawn shortly after brain death declaration. Donors who are declared brain dead by the AAN procedural criteria have been shown to react to the surgical procedure with increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, and movement of limbs (in those who have not been give neuromuscular blocking drugs), just as a living organism would respond to nociceptive stimuli.48–50 This may also be suggestive of enduring conscious awareness in donors and thus the need for general anesthesia in addition to analgesics.43,44 Heart rate variability and blood pressure responses to external stimuli are autonomic nervous system functions that are mediated by the brainstem and higher brain structures. However, the preservation of these autonomic nervous system responses to external stimuli indicate that not all brainstem functions have ceased.48,49 Furthermore, Aubinet et al have demonstrated that heart rate variability correlated with functional neuroimaging of brain connectivity in the minimally conscious state and is a more reliable indicator of conscious awareness than behavioral responses in patients with disorders of consciousness.51 Heart rate variability to external stimuli was demonstrated in the case of Jahi McMath and, although she satisfied the AAN brain death criteria, Shewmon recently postulated that she was in a minimally conscious state.47 Neuroimaging studies have indicated functional interactions between the autonomic nervous system and the higher brain structures that mediate attention and conscious processes and that heart rate variability can be useful clinically to assess the capacity for conscious awareness and residual responsiveness in disorders of consciousness.52

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the diversity in training type, level, and department that was recruited for this study, across 2 hospital campuses at the Mayo Clinic. This will perhaps add generalizability to the results and further demonstrate the need to extend the discussion around brain death to all professionals involved in the care of severely neurologically injured patients. As the World Brain Death Project aims to implement the AAN brain death procedural criteria globally, this study provides the platform for future research that should focus on surveying physicians and healthcare providers in other countries before and after this educational intervention to elucidate the generalizability of our study findings and promote this as a future direction of research.

The study findings must be interpreted upon recognizing several limitations. Most evidently, there is a low response rate, where of the 928 people contacted, 118 (13%) chose to participate. Nearly half of participants (62) did not complete both iterations of the questionnaire due to the time-intensive nature of the study. This introduces the possibility of selection bias for post-intervention responses and a smaller sample size to draw conclusions, especially on the basis of training type. In recognition and anticipation of this issue, we included the pre-intervention responses for only those who completed the study which did not show appreciable difference from the overall pre-intervention responses. This study is also marked by a failure to recruit the health professionals most closely engaged in brain death determination, as there were only 18 MDs from Critical Care, Hospital Internal Medicine, and Neurology departments.

It should also be noted that the educational intervention used in this study was curated solely by the authors. All information provided in the video presentation, however, were extracted from peer-reviewed publications and cited appropriately at the end of the presentation transcript. Given the need for brevity and the background of brain death being presented in the media and professional education as factually equivalent to biological death, the intervention was focused on the major philosophical and neuroscientific challenges to the AAN procedural criteria. A significant amount of time was spent reviewing scientific evidence against the irreversibility and completeness of brain death upon performing the AAN procedural criteria, as there is an ongoing effort to remove these conditions from the UDDA18 and, as outlined in the World Brain Death Project, to implement these revised procedural criteria globally as the universal medical standard.20 Furthermore, the authors were unable to locate further scientific evidence in defense of irreversible and complete cessation of brain function as currently mandated by the UDDA, and this is thought to be a major driving force for the attempt to realign the UDDA with the current AAN procedural criteria. Similarly, a coherent philosophical rationale that addresses concerns left over from the President’s Council in 2008 has yet to be formulated.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the existing knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals with increased exposure to severe neurologic injury toward the concept and the AAN procedural criteria for brain death, and then showed the potential for change after a thorough reintroduction to the issue. There is familiarity around the AAN criteria for brain death but deeper understanding is lacking across training type. Results show a tenuous belief that a positive result upon AAN procedural criteria marks irreversible whole-brain death as defined by the UDDA, with particular doubt that complete loss of all functions of the brain is demonstrated. Participants are clear in their support for the concept of brain death, but when answering why brain death is death, they contradictorily hold their agreement that the loss of consciousness and spontaneous breathing is sufficient for death while often agreeing that the loss of another bodily function is necessary for death. Despite all this, broad agreement behind the current practice as best clinical practice exists at baseline and remains. The lack of coherent and consistent agreement around central questions alongside an increased desire for further discussion show that this endorsement of the current practice, though widely-held and resilient, is at the same time tenuous and questionable.

Future Directions

Again citing the ongoing effort by the World Brain Death Project to implement the AAN brain death procedural criteria globally, we will end by sharing that the next step of this research is to conduct a worldwide extension with the same study design. This would entail distributing the developed educational intervention that outlines contemporary philosophical and neuroscientific challenges to the validity of the AAN procedural criteria to healthcare professionals involved in brain death in other countries with a pre- and post-intervention survey to see if this influences the acceptance of the AAN procedural criteria as the valid standard of irreversible and complete brain death determination.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author’s Note: KC, MYR, JVL, RJB authorship credit, based on: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published. Final Manuscript approved by all authors. Manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal. Project approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Protocol #19-009911) and adherent to ethical guidelines including use of informed consent for questionnaire data. Permission is hereby granted to reproduce all submitted materials, including tables and figures.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Krishanu Chatterjee, BA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7824-7957

Mohamed Y. Rady, BChir, MB (Cantab), MA, MD (Cantab) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4838-2242

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Mollaret P, Goulon M. ‘Le coma dépassé’. Rev Neurol(Paris). 1955;101(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvard Medical School, Ad Hoc Committee. A definition of irreversible Coma. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1968;205:337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Uniform Determination of Death Act: An Effective Solution to the Problem of Defining Death. Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1982;39:1511. Accessed 19 January 2021. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol39/iss4/14 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijdicks EFM. How Harvard defined irreversible coma. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(1):136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truog R, Pope T, Jones D. The 50-year legacy of the Harvard report on brain death. JAMA. 2018;320(4):335–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wijdicks E, Varelas P, Gronseth G, Greer D, American academy of neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults. Neurology. 2010;74(23):1911–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkle C, Sharp RR, Wijdicks EF. Why brain death is considered death and why there should be no confusion. Neurology. 2014;83(16):1464–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aviv R. What does it mean to die. The New Yorker, Published in the print edition of the February 5, 2018, issue, with the headline “The Death Debate.”.Accessed 19 January 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/02/05/what-does-it-mean-to-die

- 9.The President’s Council on Bioethics. Controversies in the determination of death: a White Paper by the President’s Council on Bioethics. 2008. Accessed 19 January 2021. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/reports/death/

- 10.Bernat JL, Culver CM, Gert B. On the definition and criterion of death. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94(3):389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shewmon DA. Chronic “brain death”: meta-analysis and conceptual consequences. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shewmon DA. Brain death: a conclusion in search of a justification. Hastings Cent Rep. 2018;48(6):S22–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanke G., Rady MY, Verheijde JL. When brain death belies belief. J Relig Health. 2016;55(6):2199–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer P. The challenge of brain death for the sanctity of life ethic. Ethics and Bioethics (in Central Europe). 2018;8(3-4):153–165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verheijde J, Rady MY, Potts M. Neuroscience and brain death controversies: the elephant in the room. J Relig Health. 2018;57(5):1745–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanke G, Rady MY, Verheijde JL. Ethical and legal concerns with Nevada’s brain death amendments. J Bioeth Inq. 2018;15(2):193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanke G, Rady MY, Verheijde JL. In re guardianship of Hailu: the Nevada Supreme Court casts doubt on the standard for brain death diagnosis. Med, Sci, Law. 2017;57(2):100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis A, Bonnie RJ, Pope T. It’s time to revise the uniform determination of death act. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):143–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis A, Bernat JL, Blosser S, et al. An interdisciplinary response to contemporary concerns about brain death determination. Neurology. 2018;90(9):423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greer DM, Shemie SD, Lewis A, et al. Determination of brain death/death by neurologic criteria: The world brain death project. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1078–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen D. Does the uniform determination of death act need to be revised? The Linacre Q. 2020;7(3):317–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veatch RM, Ross LF. Defining Death a Case for Choice. Georgetown University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis A, Adams N, Varelas P, Greer D, Caplan A. Organ support after death by neurologic criteria: results of a survey of US neurologists. Neurology. 2016;87(8):827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joffe AR, Anton NR, Duff JP, Decaen A. A survey of American neurologists about brain death: understanding the conceptual basis and diagnostic tests for brain death. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joffe AR, Anton N. Brain death: understanding of the conceptual basis by pediatric intensivists in Canada. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joffe AR, Anton N, Mehta V. A Survey to determine the understanding of the conceptual basis and diagnostic tests used for brain death by neurosurgeons in Canada. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(5):1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greer DM, Wang HH, Robinson JD, Varelas PN, Henderson GV, Wijdicks EF. Variability of brain death policies in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(2):213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hejazi SS, Jouybari L, Nikbakht S, et al. Knowledge and attitudes toward brain death and organ donation in Bojnurd. Electron Physician. 2017;9(7):4746–4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeon K, Kim B, Kim H, et al. A study on knowledge and attitude toward brain death and organ retrieval among health care professionals in Korea. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(4):859–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Bshabshe AA, Wani JI, Rangreze I, et al. Orientation of university students about brain-death and organ donation: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(5):966–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis A, Kreiger-Benson E, Kumpfbeck A, et al. Determination of death by neurologic criteria in Latin American and Caribbean countries Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;16(3):480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tawil I, Gonzales SM, Marinaro J, Timm TC, Kalishman S, Crandall CS. Do medical students understand brain death? A survey study. J Surg Edu. 2012;69(3):320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohod V, Kondwilkar B, Jadoun R. An institutional study of awareness of brain-death declaration among resident doctors for cadaver organ donation. Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61(12):957–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis A, Howard J, Watsula-Morley A, Gillespie C. An educational initiative to improve medical student awareness about brain death. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;167:991105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammad S, Alnammourah M, Almahmoud F, Fawzi M, Breizat AH. Questionnaire on brain death and organ procurement. Exp Clin Transplant. 2017;15(Suppl 1):121–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). JMLA. 2018;106(1):142–144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis A, Kitamura E, Padela AI. Allied Muslim healthcare professional perspectives on death by neurologic criteria. Neurocrit Care. 2020;33(2):347–357. doi:10.1007/s12028-020-01019-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rady MY. Objections to brain death determination: religion and neuroscience. Neurocrit Care. 2019;31(2):446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernat JL. A defense of the whole-brain concept of death. The Hastings Cent Rep. 1998;28(2):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nair-Collins M, Green SR, Sutin AR. Abandoning the dead donor rule? A national survey of public views on death and organ donation. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(4):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado C, Kerein J, Ferrer Y, Portela L, de la C García M, Manero JM. The concept of brain death did not evolve to benefit organ transplants. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(4):197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rady MY, Verheijde JL. Advancing neuroscience research in brain death: an ethical obligation to society. J Crit Care. 2017;39:293–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katznelson G, Katznelson G, Clarke H. Revisiting the anaesthesiologist’s role during organ procurement. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2018;50(2):91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez WJ. The trouble with anesthetizing the dead. The Linacre Q. 2019;86(4):271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morales N. ‘Dead’ man recovering after ATV accident. @NBCNews.com. March 23, 2008. Accessed 19 January 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23768436

- 46.Machado C, DeFina PA, Estévez M, et al. A reason for care in the clinical evaluation of function on the spectrum of consciousness. Funct Neurol Rehabil Ergon. 2017;7(4):43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shewmon DA. Truly reconciling the case of Jahi McMath. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(2):165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conci F, Di Rienzo M, Castiglioni P. Blood pressure and heart rate variability and baroreflex sensitivity before and after brain death. J Neurol Neuros & Psych. 2001;71(5):621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Machado C, Estevez M, Perez-Nellar J, Schiavi A. Residual vasomotor activity assessed by heart rate variability in a brain-dead case. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014205677. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riganello F, Chatelle C, Schnakers C, Laureys S. Heart rate variability as an indicator of nociceptive pain in disorders of consciousness? J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riganello F, Larroque SK, Bahri MA, et al. A Heartbeat away from consciousness: heart rate variability entropy can discriminate disorders of consciousness and is correlated with resting-state fMRI brain connectivity of the central autonomic network. Front Neurol. 2018;9:769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riganello F, Larroque SK, Di Perri C, Prada V, Sannita WG, Laureys S. Measures of CNS-autonomic interaction and responsiveness in disorder of consciousness. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.