Abstract

There is surprisingly little empirical research examining issues of fidelity of implementation within the early childhood education literature. In the MyTeachingPartner project, 154 teachers were provided with materials to implement a supplemental classroom curriculum addressing six aspects of literacy and language development. The present study examines the degree of variability in three aspects of implementation fidelity – dosage, adherence, and quality of delivery – and whether these components of fidelity were associated with children’s growth in language and literacy skills across the preschool year. Findings indicate that teachers reported using the curriculum fairly often (dosage) and that they were observed to generally follow curricular lesson plans (adherence). In contrast, the quality of delivery, defined as the use of evidence-based teacher-child interactions for teaching literacy and language, was much lower. Children in classrooms in which activities were observed to last for longer (dosage) and in which teachers exhibited higher quality of delivery of literacy lessons made significantly greater gains in early literacy skills across the preschool year. Also, teachers’ use of higher quality language interactions was associated with gains for children who did not speak English at home. Results have implications for teacher professional development and the supports provided to ensure that curricula are delivered most effectively.

Teachers in early childhood settings are increasingly required to implement content-specific curricula that systematically address children’s learning in literacy and language, math, and social development. New pressure to implement content-oriented curricula stems from an increasing focus on improving children’s academic achievements as well as evidence that exposure to explicit learning opportunities may enhance the effectiveness of early childhood programs (Clements & Sarama, 2007; Hamre, Downer, Kilday, & McGuire, 2008; Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research Consortium, 2008). Unfortunately, teachers often have difficulty implementing curricula in the ways that developers intend (Ginsburg et al., 2005; Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, & Pianta, 2008).

Studies from K-12 curricular research (see O’Donnell, 2008, for review) as well as school-based prevention (Greenberg, Domitrovich, Graczyk, & Zins, 2005) suggest that curricula implemented without a high degree of fidelity will fail to produce the intended benefits. The importance of examining implementation fidelity during the evaluation of interventions has been recognized for decades (Carroll, Patterson, Wood et al., 2007; Moncher & Prinz, 1991; Sechrest, West, Phillips, Redner, & Yeaton, 1979). There is, however, surprisingly little empirical research examining issues of fidelity of implementation within the early childhood education literature (see Clements & Sarama, 2008; Mishara & Ystgaard, 2006; Zvoch, Letourneau, & Parker, 2007). As an example of the field’s relative inattention to fidelity as a potentially influential factor governing the impacts of curricula on child outcomes, the recent comprehensive study of the effectiveness of 14 preschool curricula led by the U.S. Department of Education (Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research [PCER], 2008) did not include measures of teacher implementation fidelity in its consideration of moderators of child outcomes.

The current study examines implementation fidelity within the context of the MyTeachingPartner project (MTP: Pianta, Mashburn, Downer, Hamre, & Justice, 2008). Teachers were provided with materials to implement a supplemental classroom curriculum addressing six aspects of literacy and language development – the MyTeachingPartner – Language and Literacy Curriculum (MTP-LL; Justice, Mashburn, Hamre et al., 2008; Justice, Pullen, Hall, & Pianta, 2003) - and we examined the degree to which three aspects of implementation fidelity – dosage, adherence, and quality of delivery – were associated with children’s growth in specific language and literacy skills across the preschool year. The MTP study design focused on variations in levels of professional development support and thus did not allow for an overall test of the efficacy of the MTP-LL curriculum. Thus to assess the potential impact of the curriculum on children’s development of early literacy and language skills, this paper focuses on the extent to which teachers who implemented the curriculum more often and with higher quality had students who made greater gains in literacy and language across the preschool year. Below we provide an overview of the MTP-LL curriculum followed by a summary of research on implementation fidelity and a description of the current study.

MyTeachingPartner—Language and Literacy Curriculum

MTP-LL includes a comprehensive set of explicit instructional activities encompassing six language and literacy domains. These activities were designed to focus on (1) “high-priority” instructional targets in preschool language and literacy, and (2) effective approaches to translating these instructional targets into high-quality, sustainable classroom instruction. A high priority target for preschool language and literacy instruction is one that (a) is consistently and moderately to strongly linked to later achievements in word recognition and/or reading comprehension, (b) is amenable to change through intervention, and (c) is likely to be underdeveloped among pupils experiencing risk (Lonigan, 2004). The six targets for MTP-LL were based on the conclusions of several meta-analyses (e.g., Hammill, 2004; National Early Literacy Panel [NELP], 2004) and longitudinal studies identifying specific early language and literacy skills predictive of later reading skills (e.g., Bryant, MacLean, & Bradley, 1990; Chaney, 1998; Christensen, 1997; Gallagher, Frith, & Snowling, 2000; Schatschneider, Fletcher, Francis, Carlson, & Foorman, 2004; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002).

The first three targets (phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, print awareness) are conceptualized as “code-based” literacy skills that tend to be predictive of later skills in word recognition, can be directly affected through targeted classroom-based interventions (e.g., Justice & Ezell, 2002; Ukrainetz, Cooney, Dyer, Kysar, & Harris, 2000; van Kleeck, Gillam, & McFadden, 1998; Whitehurst, Epstein, Angell, Crone, & Fischel, 1994), and are typically underdeveloped in pupils experiencing risk (e.g., Bowey, 1995; Lonigan, Bloomfield et al., 1999; Snowling, Gallagher, & Frith, 2003). The latter three targets (vocabulary/linguistic concepts, narrative, social communication/pragmatics) are conceptualized as “meaning-based” language skills also associated with later reading and academic success, with particular associations to outcomes in reading comprehension for the former two (Pankratz, Plante, Vance, & Insalaco, 2007; Storch & Whitehurst, 2002) and social/behavioral competencies for the latter (e.g., Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, & Cox, 2000). These three aspects of early development tend to be areas of relative disadvantage for children reared in poverty (e.g., Fazio, 1994; Justice, Bowles, & Skibbe, 2006) that can be readily improved through targeted interventions (Lonigan, Anthony, et al. 1999; Penno, Wilkinson, & Moore, 2002; Reese & Cox, 1999; Whitehurst et al., 1988). By addressing all six targets within a single curriculum, the MTP-LL offered a relatively more comprehensive approach to early language and literacy instruction than has been typical (e.g. Aram & Biron, 2004; Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1991; van Kleeck et al., 1998), although an increasing number of targeted curricula are available that address these or similar sets of language and literacy objectives in an explicit and systematic manner (e.g., see PCER, 2008).

Implementation Fidelity

In this study, we examined three aspects of MTP-LL implementation fidelity anticipated to impact the extent to which the curriculum produced intended effects on children’s literacy and language skill development: dosage, adherence, and quality of delivery. Dosage is typically defined as the frequency and duration of an intervention. Measures of dosage of a curriculum typically take into account the number, length, or frequency of curricular activities to which children are exposed (O’Donnell, 2008). In this study dosage was assessed through teacher reports of the frequency with which they used MTP-LL activities as well as the observed length of those activities. Adherence is defined as the “degree to which program components were delivered as prescribed” (Greenberg et al., 2005). For the purpose of curricular research, adherence generally assesses the extent to which teachers stay true to lesson guides or scripts in their delivery of content. Adherence is typically measured through teacher report, though occasionally it may be rated by observers. Within this study, adherence was assessed through an observational rating of the extent to which teachers followed the lesson scripts, used materials as intended, and completed all aspects of an activity.

In contrast to these two aspects of fidelity of implementation, which are fairly consistent in their conceptualization and measurement across studies and even disciplines, there is little consensus in either educational or school-based prevention work about how to actually conceptualize and measure quality of delivery (Domitrovich & Greenberg, 2000; Dusenbury et al., 2003; Greenberg et al., 2005; O’Donnell, 2008). Definitions range from “the quality of interaction and the degree to which interactive activities focus attention on desired elements” (Dusenbury et al., 2003, p. 244) to “the affective nature or degree of engagement of the implementers when delivering the program” (Greenberg et al., 2005, p. 30). Researchers from the field of education have suggested that quality of delivery is synonymous with good teaching (O’Donnell, 2008). Yet, very few studies on early childhood teaching have included measures of quality of delivery, and when they do these measures are often developed for use with only one curriculum or intervention. This has made generalizing findings about quality of delivery challenging. In this study, we tested the degree to which conceptualizing (and measuring) quality of delivery through the lens of observed teacher-child interactions may enhance our understanding of the variability inherent in curricular implementation and help explain variance in child outcomes.

Teacher-Child Interactions as a Measure of Quality of Delivery

Hamre and Pianta (2007) recently provided a framework for effective teaching referred to as the CLASS Framework. The CLASS Framework is based on developmental theory suggesting that children are most directly influenced through proximal processes, namely, their daily interactions with adults and peers (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). These interactions may be social-emotional, managerial and organizational, or instructional in nature (Hamre & Pianta, 2007). Of relevance to the present study, Hamre and Pianta (2007) suggested that there are two aspects of high-quality instruction, both focused on the quality of teacher-child interactions. The first, referred to as generalized teaching strategies, focuses on the types of teacher-child interactions that are relevant across content areas and grades. This includes aspects of teaching such as classroom climate, behavior management, and the quality of feedback provided to children. The second, referred to as content-specific teaching strategies, encompass the types of interactions that are most salient to the specific curriculum being implemented. In this study we examine the extent to which quality of delivery, as defined by the teachers’ use of empirically-supported literacy- and language-specific teaching strategies during the implementation of the MTP-LL curriculum, predicts gains in children’s literacy and language skills across the preschool year.

There is a growing body of work suggesting the importance of content-specific literacy and language interactions in early childhood settings. Social–interactionist theories of language acquisition (e.g., Baumwell, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 1997; Chapman, 2000; Landry, Miller-Loncar, Smith, & Swank, 1997) provide evidence that linguistically responsive facilitation strategies such as the use of open-ended questions, expansions, advanced linguistic models, and recasts are associated with positive language achievements in young children (e.g., Baker & Nelson, 1984; Nelson, 1977; Vasilyeva, Huttenlocher, & Waterfall, 2006; Wasik, Bond, & Hindman, 2006; Yoder, Spruytenburg, Edwards, & Davies, 1995). These strategies have been embedded in interventions and curricula that have direct associations with children’s language development in preschool classrooms (e.g., Dickinson, 2006; Girolametto &Weitzman, 2002; Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman, & Levine, 2002; McKeown & Beck, 2006; Wasik et al., 2006).

Similar work has defined, measured, and tested the characteristics of high-quality literacy instruction in the preschool classroom. High-quality literacy instruction features instruction that explicitly teaches children about the code-based characteristics of written language, to include both phonological and print structures (Justice, Mashburn, Hamre et al., 2008). Although this instruction may be embedded within purposeful and contextualized routines and activities (e.g., dramatic play, arts and crafts, writing), it frequently features a relatively teacher-directed orientation so as to ensure the systematicity and explicitness of literacy instruction (Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1989; Justice, Chow, Capellini, Flanigan, & Colton, 2003; van Kleeck, Gillam, & McFadden, 1998). Intervention studies indicate that children’s exposure to these types of interactions can accelerate emergent literacy development (e.g., Justice et al., 2003; van Kleeck et al., 1998; Whitehurst et al., 1988).

Many of the newer literacy and language curricula for early childhood classroom rely in large part on facilitating teacher use of these practices (see PCER, 2008 for review). However, the interpersonal nature of these practices makes them challenging to effectively script into activities. MTP-LL encouraged the use of these practices in the scripted activities and thus, to some extent we expect that they are assessed through the observational measure of adherence (i.e., did the teacher follow the script?). Yet, we anticipate that much of the success of the curriculum will depend on teachers’ abilities to pick up on these instructional strategies and use them to enhance activity beyond what is provided in the scripted lesson – it is this aspect we define as quality of delivery.

Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, et al. (2008) reported on a new measure for observing these content-specific teaching practices in early childhood classrooms. Two new scales were added to the existing Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS: Pianta, LaParo, et al., 2008) – Language Modeling and Literacy Focus. Although observations of these instructional practices during the implementation of the first two months of MTP-LL activities were relatively low (between 2.19 to 3.06 on a seven point scale), there was evidence that the MTP-LL activities led to increases in the use of specific practices. Language Modeling scores were significantly higher during the implementation of language activities while Literacy Focus scores were significantly higher during the implementation of literacy activities. The current paper extends previous work by assessing the extent to which these aspects of instruction during MTP-LL activities are associated with gains in children’s skills.

Implementation Fidelity and Student Outcomes

Given the inconsistent definition and measurement of implementation fidelity as applied to early childhood curricula and instruction, it is not surprising to find few examples linking implementation fidelity to student outcomes. Several meta-analyses of school-based interventions conducted in the 1990s indicated that only 15–59% of reviewed studies measured and reported implementation fidelity (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger,1999), and these measurements often covered only one element of implementation (e.g., exposure). In a recent review of research concerning K-12 curriculum interventions, O’Donnell (2008) indicated that assessments of implementation are even less common in research on specific curricula. Those studies that did examine links between implementation fidelity and pupil outcomes tended to focus on adherence or dosage with very few including any measures of quality of delivery.

Examples of links between implementation fidelity and pupil outcomes in early childhood settings are particularly rare. One notable exception is recent work by Clements and Sarama (2008), which included extensive classroom observations collected during a randomized control trial of two math curricula – Building Blocks and Preschool Mathematics Curriculum (PMC, Klein, Starkey, & Ramirez, 2002) – and a control condition. Three of the items on the observational measure of implementation fidelity significantly predicted gains in children’s math knowledge over the course of the year: the percentage of time the teacher was actively engaged in activities; the degree to which the teacher built on and elaborated children’s mathematical ideas and strategies; and the degree to which the teacher facilitated children’s responding. Another recent study focused on a comprehensive language development curriculum (Justice, Mashburn, Pence, & Wiggins, 2008) suggests links between teachers’ use of the curriculum’s language facilitation strategies and greater growth in children’s language over the year.

Various components of implementation may also be more or less important for certain subsets of children. In the case of literacy and language development, for instance, there are two child characteristics that we expect may moderate associations between implementation fidelity and children’s gains in literacy and language skills across the preschool year. First, there is evidence that children entering preschool with very low levels of literacy skill may respond quite differently to different types of instructional strategies than children with higher levels of skill (Justice et al., in press). Work by Connor, Morrison, and colleagues (Connor, Morrison, & Petrella, 2004; Morrison & Connor, 2002) suggests that children with low skill levels may benefit most from high levels of teacher-managed explicit language and literacy instruction, whereas highly skilled children benefit more from child-managed activities. Given that the MTP-LL activities largely center about explicit, teacher-managed instruction, we anticipated that implementation fidelity would be most closely associated with outcomes for children entering preschool with the lowest level of skills in early literacy.

Another potential moderator of links between implementation fidelity and child outcomes is the language ability of the child. There is very little empirical evidence yet to suggest how native and non-native English speakers may differentially respond to specific types of literacy and language instruction within early childhood classrooms (Downer, Lopez, Hamagami, Howes, & Pianta, 2009). In general, however, work on child-level moderators of the effects of classroom interactions suggest that children at-risk are more likely to benefit from high-quality instruction (e.g., Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Connor et al., 2004). Thus, we hypothesized that implementation fidelity would be most closely associated with gains in literacy and language outcomes for non-native English speakers.

Current Study

In this study, we examined the extent to which the fidelity with which teachers implemented an explicit and systematic language and literacy supplemental curriculum – MTP-LL -- was associated with children’s growth in language and literacy skills during preschool. We examined three components of fidelity of implementation of MTP-LL: dosage, adherence, and quality of delivery. Four research questions were addressed: (a) what is the range of implementation fidelity among teachers implementing MTP-LL?; (b) to what extent are there interrelations among the three components of implementation fidelity and to what extent do each of these relate to generalized teaching strategies?; (c) to what extent are dosage, adherence, and quality of implementation associated with preschool children’s growth in language and literacy skills across the preschool year, above and beyond generalized teaching strategies?; and (d) to what extent are relations between implementation fidelity and child outcomes moderated by child characteristics?

Method

Participants

Participants in this study included 154 preschool teachers and 680 children enrolled in their classrooms. The teachers represented a subset of those involved in a larger study of teacher and child impacts associated with implementation of the MTP-LL curriculum in conjunction with a social/emotional development curriculum [Preschool PATHS (Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies); Domitrovich, Greenberg, Kusche, & Cortes, 2004)] conducted in state-funded preschools in a mid-Atlantic state. As part of the larger study, teachers were randomly assigned to conditions representing planned variations in professional development. For the present study, teachers were included for analysis based on whether they submitted at least one videotaped lesson over the course of the 2004–2005 school year. Although at the low end (one tape) this is a small sampling of teacher behavior, other studies suggest relatively high stability in teaching practice across various time sampling (Chomat-Mooney, Pianta, Hamre, et al. 2008). This led to a sample of 154 of the 171 teachers who participated in the first year of the study, or 90% of teachers.

The teachers involved in this study all taught in classrooms that prioritized entry for four-year-old children who exhibited some degree of specific risk factors, including poverty, homelessness, developmental delays, limited English proficiency, or a variety of family and social stressors (e.g., parents are school drop-outs or are chronically ill). The teachers had an average of 9.2 years of experience (SD = 7.81), with a range of zero to 33 years. Due to program requirements, all teachers held at least a bachelor’s degree (37% had a degree in Early Childhood Education), and 34% held an advanced degree. Classroom composition was, on average, 48% male and 27% White. The percentage of students in a given class that were classified as being Limited English Proficient was 12%, although there was considerable variability (0 to 100%). There were not significant differences in teacher or classroom characteristics between the selected teachers and all teachers in the study.

The child participants in this study were selected from among all the children in their classrooms at the beginning of the school year based on the following procedures. First, parental consent agreements were mailed home to all children within a class and were collected by the children’s teachers. Second, four to five children whose parents provided consent were randomly selected from each classroom. In addition, if a selected child was no longer enrolled in the classroom at the end of the year, a new child from within the classroom was randomly selected to participate.

Demographic characteristics for the 680 randomly selected children who participated in the study are presented in Table 1. The sample was approximately half (51%) girls. Nineteen percent of the children spoke a language other than English in the home and their mothers had, on average, just over a high school education (12.8 years).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Child Participants (n=680)

| n | % | Missing | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child and Family Characteristics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Boy | 326 | 49% | 14 | ||

| Girl | 340 | 51% | |||

| Language(s) spoken at home | |||||

| English only | 545 | 81% | 12 | ||

| Other language | 125 | 19% | |||

| Age at Entry | 668 | 12 | 4.38 | 0.31 | |

| Maternal education (years) | 660 | 20 | 12.8 | 2.08 | |

| Language and Literacy Assessments | |||||

| Fall Receptive Vocabulary | 615 | 65 | 30.3 | 4.0 | |

| Spring Receptive Vocabulary | 583 | 97 | 33.7 | 3.5 | |

| Fall Phonological Awareness | 588 | 92 | 26.2 | 5.4 | |

| Spring Phonological Awareness | 576 | 104 | 30.6 | 5.3 | |

| Fall Print Awareness | 607 | 73 | 16.7 | 9.1 | |

| Spring Print Awareness | 583 | 97 | 28.6 | 7.5 | |

| Fall Emergent Literacy Composite | 549 | 131 | 34.4 | 16.7 | |

| Spring Emergent Literacy Composite | 555 | 125 | 59.4 | 12.6 | |

Note: Receptive Vocabulary, Phonological Awareness, and Print Awareness scores from the Pre-CTOPPP (Lonigan et al., 2003); Emergent Literacy Composite from the PALS-PreK (Invernizzi et al., 2004).

Procedures

Curriculum.

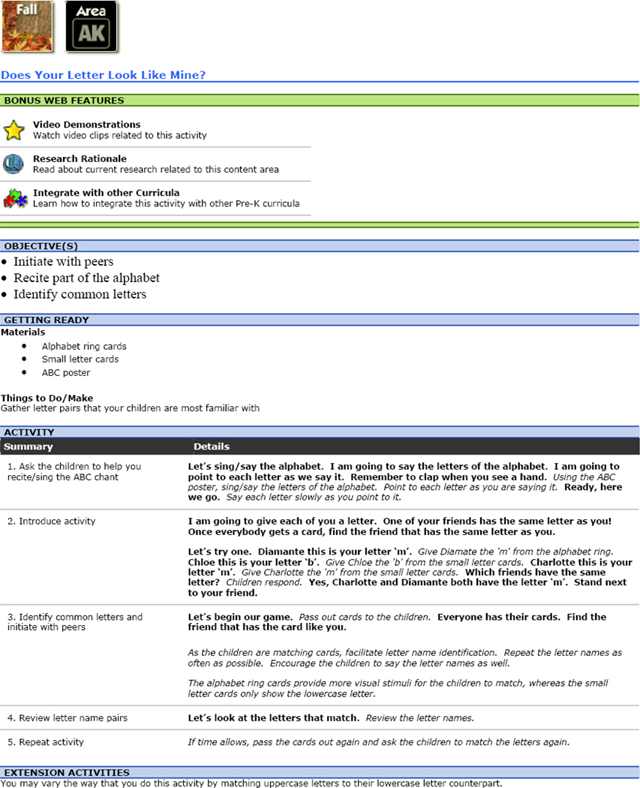

The curriculum implemented in this study was the 36-week MyTeachingPartner-Literacy & Language (MTP-LL). MTP-LL addresses six domains of language and literacy development (phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, print awareness, vocabulary/linguistic concepts, narrative, social communication/pragmatics) and provides teachers with numerous activities to implement within their classroom each day to address these domains and associated instructional objectives. Teachers were asked to implement at least six of the MTP-LL language and literacy activities each week (one from each area) as a supplement to their usual curriculum. Teachers were provided with a suggested set of activities each week, but were given flexibility to pick and choose activities from a larger pool. Each activity consisted of an instructional objective, scripted activity sequence, materials, and extension activities (see Appendix A for a sample activity). Although the activities were designed to be conducted as a part of whole or small groups, the majority of teachers choose to implement activities in whole group.

To prepare teachers for use of the curriculum, teachers in the study attended a two-day professional development workshop near the beginning of the academic year that provided an overview of MTP-LL and modeled effective implementation of curricular activities. At this time, teachers were also familiarized with the MTP website, including exemplary video clips of activities.

Coding of videotapes.

As part of their participation in the study, teachers were asked to videotape themselves implementing MTP-LL language and literacy activities once each month (nine for the year) and to submit these videotapes to the research site by mail. In collecting these videos, teachers were asked to film a few minutes prior to the start of the activity, the full activity, and the time following the activity up to at least 30 minutes. Tapes were selected for coding based on obtaining an adequate sampling of teaching across the school year – thus all tapes available within three windows (September/October, January/February, April/May) were selected for coding. On average, 4.5 tapes that included an MTP-LL activity were coded per teacher (range 1 to 9). The vast majority of teachers (88%) had at least three tapes coded.

Selected tapes were coded twice. The first coding comprised a single 30-minute viewing of the videotape, from the first moment in which teachers and children were visible to 30 minutes or when the tape ended, whichever came first. This coding session was used to assess the overall quality of the interactions, representing generalized teaching strategies (described below). Typically this coding included the MTP-LL activity in addition to some introductory activities and/or transition activities. Because teachers were filming themselves, very little of the footage was center-based or free play. The second coding was based on viewing only the MTP-LL activity; this coding focused on documentation of implementation fidelity, including an adherence checklist and application of quality of delivery codes (described below). The second coder watched until the MTP-LL was completed – at times this extended beyond the 30-minutes coded by the first coder.

Measures

Teacher, child, and family characteristics.

Teachers completed a demographic survey reporting information on their degree, their major area of study, years of experience in pre-k education, and professional development experiences. Parents of each child in the study completed a brief family questionnaire that assessed the following child and family characteristics: gender, language spoken in the home, and years of maternal education.

Generalized teaching strategies.

Measurement of teachers’ generalized teaching strategies was coded for the first 30-min of each videotaped activity using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System- Pre-K (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, et al., 2008) by a team of trained and reliable coders. The CLASS is an observational measure used to quantify the quality of teacher-child interactions in classroom settings. The CLASS assesses 10 dimensions representing three domains: Emotional Support [Positive Climate, Negative Climate (reverse scored), Teacher Sensitivity, and Regard for Student Perspectives]; Classroom Organization, [Behavior Management, Instructional Learning Formats, and Productivity]; and Instructional Climate, [Concept Development, Quality of Feedback, and Language Modeling]. Each dimension is scored on a seven-point scale that encompasses low (1, 2 points), mid (3, 4, 5 points), and high (6, 7 points) ratings of quality. Higher scores on these dimensions of teacher-child interactions have predicted growth in pre-k children’s achievement and social adjustment (Howes et al., 2008; Mashburn, et al., 2008).

For the present paper, we were interested in generating an overall summary of teaching performance. Thus, for each teacher, an aggregate score for each dimension was created by averaging the eight average dimension scores (Positive Climate, Negative Climate (reverse scored), Teacher Sensitivity, Behavior Management, Instructional Learning Formats, Productivity; Concept Development, and Quality of Feedback). Two CLASS scales were not used for this study. Regard for Student Perspectives was revised during the middle of this study (from a previous version called Overcontrol) and was thus omitted from analysis. One other CLASS dimension, Language Modeling, was not included in the composite for this study because it was used as a measure of quality of delivery. Cronbach’s alpha for the Overall Teaching Quality score was .91 for this sample.

All CLASS coding was conducted by a team of trained and reliable CLASS coders. Prior to coding videotapes for this study, reliability was determined by a test in which coders scored three videos and had to score within one point of each dimension on at least 80% of the codes to be considered reliable. During the coding process, inter-rater reliability for each CLASS dimension was computed by comparing the scores provided by two independent coders for 33 randomly-selected tapes (5%). Codes were considered to be in agreement if they were within one point of each other on the seven-point scale; agreement ranged from 79% for Instructional Learning Formats to 97% for Productivity. These levels of inter-rater reliability are comparable to that reported for the CLASS (both Pre-K and Elementary versions) when used for live observation in large scale observational studies (La Paro, Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004; NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2005; Pianta, Downer, et al., 2008). In addition, coders met once a week to code a videotape together, to check for coder accuracy and provide feedback.

Implementation fidelity: Dosage.

Two dosage variables were included. At the end of the school year, teachers were asked to report on the typical number of days per week, in a typical week, that they completed MTP activities. They were also asked to report on how many minutes each activity typically took to complete. These two items were multiplied to create an average number of minutes per week that teachers reporting using MTP-LL activities. The second measure of dosage was the average observed length of MTP-LL activities across all coded videotapes.

Implementation fidelity: Adherence.

A nine-item MTP – Implementation Checklist was completed for portions of the videos in which teacher were implementing MTP-LL activities. Each item was scored as either present (1) or not present (0). The portions of the checklist used for this study include the four items that most directly assessed adherence: (1) teacher language is in general accordance to the script in the activity plan; (2) teacher has all listed materials available and easily accessible; (3) all listed materials are used in general accordance with the activity plan; and (4) all components of the lesson are completed. Scores for individual items were summed to create an overall adherence score, which was then averaged across the year, with a possible score range of zero to four points. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .73.

Coders were trained on the MTP Implementation Checklist and took a reliability test that consisted of watching and coding four videos. Coders had to obtain 80% exact agreement on these master coded videos to begin coding tapes for this study. To assess reliability of coding procedures as implemented by these trained coders, a subset of tapes (approximately 10%) was double coded; coders assigned the same binary rating for 89% of the items.

Implementation fidelity:

Quality of delivery was assessed using two new scales for the CLASS that focus on these aspects of classroom interactions – Language Modeling and Literacy Focus. These codes were obtained during the second coding, in which observers only watched the portion of tape in which teachers were delivering an MTP-LL activity. Language Modeling assesses the degree to which teachers use strategies which facilitate discussion and increasingly complex language use by children (e.g., repetition, extension, self-talk, advanced vocabulary). Literacy Focus assesses the degree to which teachers explicitly direct children’s attention to code-based aspects of oral and written language, as well as the degree to which teachers make the connection between code-based activities and the broader, more functional, purposes of written or spoken language. For example, as a teacher is introducing an alphabet poster that features capital letters, the teacher may state, “These are capital letters. Your name starts with a capital letter. Grace, your name would start with this letter (points to letter). Capital ‘G’ is the first letter in your name.” She is explicitly drawing attention to letters and has clearly connected the value of capital letters to something of meaning in the children’s lives, their name. At the high end of the scale these types of interaction are observed consistently. Composite scores for Literacy Focus and Language Modeling were created using the same method described above for the overall CLASS score. On segments that were double coded, Language Modeling and Literacy Focus scales were within one point of each other for 83% and 88% of observations, respectively.

Child direct assessments.

The study included administration of subtests from two direct assessments of children’s language and literacy skills: the Phonological Awareness and Literacy Screening-PreKindergarten (PALS; Invernizzi, Sullivan, Meier, & Swank, 2004) and the Preschool Comprehensive Test of Phonological and Print Processing (Pre-CTOPPP; Lonigan, Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 2002). Teachers administered both assessments to the children in their classrooms who were enrolled in this study. Small-scale pilot tests have demonstrated the reliability and validity of data collected by assessments administered by teachers in Head Start classrooms (e.g., Head Start National Reporting System). In addition, because PALS is the statewide preschool literacy screening used across the state in which the study was conducted, most teachers had administered PALS to children in their classrooms in the past and were very familiar with its testing procedures. At the beginning of the project, all teachers completed training focused on administration of the language and literacy battery. Teachers videotaped all of these assessments and submitted these to research staff at the same time they submitted children’s score forms. Fidelity of teachers’ administration was checked via videotape for a randomly selected 20% of teachers. Teachers accurately administered standardized items over 90% of the time and reported that for 96% of the assessments children’s performances were “most typical” or “very typical” of their usual classroom functioning.

The PALS-PreK is a standardized, criterion-referenced assessment of children’s emergent literacy skills that includes measurement of phonological awareness (Rhyme and Beginning Sounds subtests), print knowledge (Alphabet Knowledge, Print and Word Awareness, and Concept of Word subtests), emergent writing (Name Writing subtest), and verbal memory (Verbal Memory subtest). It is designed for use with children who are three- to five-years of age. Raw scores for each of the individual subtests are summed to create an emergent literacy composite score that was used for analyses in the present study as an index of children’s general emergent literacy abilities. Psychometric qualities include acceptable levels of test-retest and inter-rater reliability, and concurrent validity (Invernizzi, 2000).

The Pre-CTOPPP (Lonigan et al., 2002) is a standardized norm-referenced test designed for use with children from three to five years of age, and is the precursor to the slightly revised and recently published Test of Preschool Early Literacy (Lonigan, Wagner, & Torgesen, 2007). The Pre-CTOPPP provides an assessment of children’s phonological awareness, print awareness, and receptive vocabulary. Standard scores for the test version utilized are not available, because national norms for these versions of the subtests were not disseminated; therefore, for our purposes, raw scores are reported and used in analyses. Phonological awareness is assessed through the Blending and Elision subtests. The Blending subtest includes items that measure whether children can blend initial phonemes onto one-syllable words, initial syllables onto two-syllable words, and ending phonemes onto one-syllable words. The Elision subtest measures whether children can break apart initial and ending phonemes, as well as initial syllables, from one- and two-syllable words. Print Awareness items measure whether children recognize individual letters and letter-sound correspondences, and whether they differentiate words in print from pictures and other symbols. Receptive Vocabulary items measure children’s single-word vocabulary knowledge. The Pre-CTOPPP subtests exhibit adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and concurrent validity(Lonigan, McDowell, & Phillips, 2004). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the fall and spring language and literacy assessments.

Analysis

The measures collected for this study were hierarchically nested, with approximately four children nested within each teacher’s classroom. The first two research questions, assessing the degree of variability in fidelity of implementation among teachers and the associations among the three measures of implementation fidelity, involved only classroom-level data and were descriptive in nature. The final two questions, assessing associations between measures of fidelity of implementation and child outcomes as well as the extent to which these associations were moderated by characteristics of the child, involved both classroom- and child-level data. To account for the nested structure of our measures, we conducted 2-level hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) in analysis of research questions three and four (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Specifically, to address the third research question, we examined the extent to which implementation fidelity was uniquely associated with children’s growth in language and literacy skills during pre-kindergarten, controlling for child (level-1) and teacher and classroom characteristics (level-2). The fourth research question examined the extent to which associations between implementation fidelity and children’s growth in language and literacy skills depended upon children’s home language and fall achievement scores. To test these potential moderating effects we entered an interaction term for each measure of fidelity of implementation and these two child characteristics.

Analyses that included child-level data were conducted using the PROC Mixed procedure in SAS (Singer, 1998), and missing data were estimated using multiple imputation procedures that created 20 complete data files (refer to Tables 1 and 2 for a summary of amount of missing data). The multi-level analyses were conducted for each of the 20 imputed data files, and coefficients and standard errors resulting from each analysis were aggregated. Analyses were also run on non-imputed data and all of the significant effects remained the same – thus, to best enable generalization to the entire sample, only results from imputed analyses are presented.

Table 2.

Classroom and Teacher Characteristics and Use of Intervention Components (n=154)

| n | % | Missing | Mean | Sd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom Characteristics | |||||

| Proportion Non-English at Home | 154 | 0 | .19 | .30 | |

| Mean Maternal Education (years) | 154 | 0 | 12.70 | 1.03 | |

| Teacher Characteristics | |||||

| Level of Education | 2 | ||||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 100 | 66% | |||

| Advanced Degree | 52 | 34% | |||

| Field of Study | 2 | ||||

| Early Childhood Education | 56 | 37% | |||

| Other | 96 | 63% | |||

| Years Teaching PK | |||||

| Generalized Teaching Quality | 154 | 0 | 4.43 | 0.56 | |

| Implementation Fidelity | |||||

| Dosage – Teacher Reported Minutes per Week | 142 | 12 | 100.53 | 58.11 | |

| Dosage – Observed Minutes per Activity | 154 | 0 | 24.6 | 5.0 | |

| Adherence - Observed | 154 | 0 | 3.25 | 0.70 | |

| Quality of Delivery - Language Modeling | 154 | 0 | 2.73 | 0.71 | |

| Quality of Delivery - Literary Focus | 154 | 0 | 2.46 | 0.86 | |

Results

Teachers’ Implementation Fidelity

Table 2 provides an overview of descriptive findings concerning implementation fidelity of MTP-LL. In terms of dosage, teachers reported using MTP-LL activities an average of 100 minutes per week (SD = 58), with a range of 15 to 300 minutes. Very few teachers (3.5 %) reported using the activities for 30 minutes or less. Almost half (42%) reported using the activities for over 90 minutes a week, which is approximately the length we would anticipate for full implementation (six activities, 15 minutes each). Observed activity length, a second measure of dosage, suggests than activities typically lasted somewhat longer than the suggested 15 minutes. Observed length ranged from 10.1 to 39.7 minutes, with an average length of 24.6 minutes (SD = 5.0).

Adherence also occurred at fairly high levels, as assessed by four items of the observational MTP Implementation Checklist. On the four-point scale, teachers averaged 3.25 points across the year, with a range from one to four. The mean scores for individual adherence items represent the average percent of times in which an item was scored as present across all the videos coded for a teacher across the year. Teachers language was generally observed to be in accordance with the lesson plan (M = .93). The other items were also typically observed as present, but mean scores were slightly lower: teacher has all listed materials available and easily accessible (M = .81); all listed materials are used in general accordance with the activity plan (M = .79); and all components of the lesson are completed (M = .79).

Quality of delivery, as assessed by Language Modeling and Literacy Focus scores, was much lower. Recall that these quality scores can range from one (low) to seven (high). The average Language Modeling score was 2.73 (SD = .71) and the average Literacy Focus score was 2.46 (SD = .86). Regarding the Language Modeling scores, 20% of teachers received scores of under two points, 54% of teachers received scores between two and three points, and 26% had Language Modeling above a three. Almost half of teachers (43%) received scores of less than two points on Literacy Focus, 32% of teachers received scores between two and three, and 25% scored above a three.

Associations among Implementation Fidelity Measures and Generalized Teaching Quality

The second research question concerned the interrelations among measures of implementation fidelity as well as the relations of implementation fidelity measures to an index of generalized teaching quality (see Table 3). The implementation fidelity measures were not associated with one another. Even within types of implementation fidelity, associations were low. The two dosage measures, teachers reported minutes per week and observed number of minutes per coded activity were unrelated to one another (r = .03, p = .69). Similarly, the two measures of quality of delivery, Language Modeling and Literacy Focus, showed very weak associations with one another (r = .10, p = .19), suggesting that they capture unique features of instruction. Due to the potential overlap between measures of quality of delivery and the classroom-level control variable of generalized teaching quality, we also assessed the degree of association between classrooms’ overall CLASS scores and all measures of implementation fidelity. The only significant association was that classrooms displaying higher overall generalized teaching quality, as observed during the full 30 minutes of teaching, had higher Language Modeling scores during the delivery of activities (r = .32, p < .01).

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations among Implementation Fidelity Measures (n=154).

| Dosage – Teacher Reported Minutes per Week | Dosage – Observed Minutes per Activity | Adherence - Observed | Quality of Delivery - Language Modeling | Quality of Delivery - Literary Focus | Generalized Teaching Quality (CLASS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage – Teacher Reported Minutes per Week | ||||||

| Dosage – Observed Minutes per Activity | .03 | |||||

| Adherence - Observed | .01 | −.10 | ||||

| Quality of Delivery - Language Modeling | .11 | .04 | .08 | |||

| Quality of Delivery - Literary Focus | .13 | .02 | .12 | .11 | ||

| Generalized Teaching Quality (CLASS) | .04 | .01 | .08 | .32** | .08 |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Relations between Implementation Fidelity and Gains in Children’s Literacy and Language Skills

Results of hierarchical linear models are presented in Table 4, including unstandardized coefficients (B) and standard errors (SE) that identify the magnitudes and directions of the associations between each level 1 and level 2 predictor and the four measures of children’s language and literacy skills. Considering first the level 1 predictors, in the case of all four outcomes, children’s fall scores were strongly associated with spring test performance. Children who were absent more days also displayed less growth in all assessed skills over the course of the preschool year. Children who were older at the beginning of the school year made greater gains on the measure of phonological awareness than did their younger peers. Girls made more gains in print concepts. Finally, children whose mothers had higher levels of education displayed greater growth in receptive vocabulary and phonological awareness.

Table 4.

Associations between Implementation Fidelity of MTP-LL Activities and Children’s Language and Literacy Growth

| Receptive Vocabulary | Phonological Awareness | Print Awareness | Emergent Literacy Composite | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Level-1 Child Characteristics | ||||||||

| Pre-test | .53*** | .03 | .53*** | .03 | .46*** | .03 | .41*** | .03 |

| Days between testing | −.00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 | −.02 | .02 |

| Days Absent | −.04* | .02 | −.05* | .03 | −.16*** | .04 | −.24*** | .06 |

| Entry Age | .70 | .39 | 2.22*** | .58 | 1.02 | .81 | .29 | 1.41 |

| Gender (Boy) | −.17 | .22 | −.47 | .32 | −1.02* | .49 | −.89 | .77 |

| Non-English | −.28 | .37 | −.80 | .60 | .17 | .82 | −.84 | 1.41 |

| Maternal Education (years) | .16* | .06 | .36*** | .09 | .08 | .13 | .15 | .23 |

| Level-2 Classroom Characteristics | ||||||||

| Proportion Non-English | −.40 | .61 | −1.47 | 1.09 | −1.89 | 1.58 | −9.50*** | 2.65 |

| Mean Mother’s Education | .03 | .14 | .14 | .23 | .02 | .35 | −.59 | .58 |

| Generalized Teaching Quality (Total CLASS scores) | .29 | .22 | .96* | .39 | .26 | .57 | 1.72 | .96 |

| Level-2 Implementation Fidelity | ||||||||

| Dosage – Teacher Reported Minutes per Week | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Dosage – Observed Minutes per Activity | −.01 | .02 | .03 | .04 | .05 | .06 | .20* | .10 |

| Adherence - Observed | −.17 | .16 | .35 | .30 | .34 | .43 | −.25 | .74 |

| Quality of Delivery-Language Modeling | −.09 | .19 | .28 | .35 | −.19 | .49 | .06 | .84 |

| Quality of Delivery-Literacy Focus | .05 | .13 | .01 | .24 | 1.06** | .36 | 1.73** | .59 |

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

p≤.001.

An examination of associations between the classroom characteristics included in the level-2 model and children’s spring language and literacy skills suggests that children in classrooms with a greater proportion of children from non-English speaking homes displayed significantly less growth in the emergent literacy composite over the course of the preschool year. In addition, children in classrooms displaying higher levels of overall generalized teaching quality showed more growth in phonological awareness over the preschool year.

The level-2 model also included the five measures of implementation fidelity: two indicators of dosage (teacher reported minutes per week and observed activity length), adherence, and the two indicators of quality of delivery (Language Modeling, Literacy Focus). As the data in Table 4 show, there was one main effect for dosage. Children displayed more growth in emergent literacy (d = .09) when activities were observed to be longer. The teacher-reported dosage measure was not related to any outcomes. Adherence and one of the measures of quality of delivery (language Modeling) were also unrelated to children’s growth in literacy and language skills over the course of the preschool year. In contrast, the Literacy Focus component of the quality of delivery measure was related to growth in children’s literacy skills. Specifically, children in classrooms in which teachers received higher quality of implementation rates for Literacy Focus made greater gains in both print awareness (d = .12) and the emergent literacy composite (d = .12) over the preschool year.

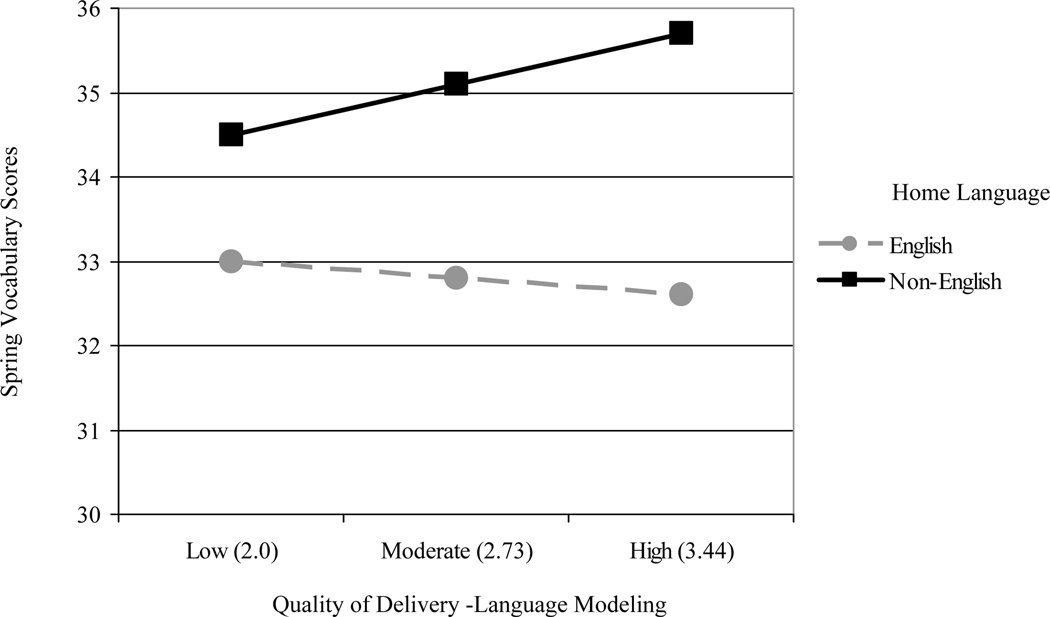

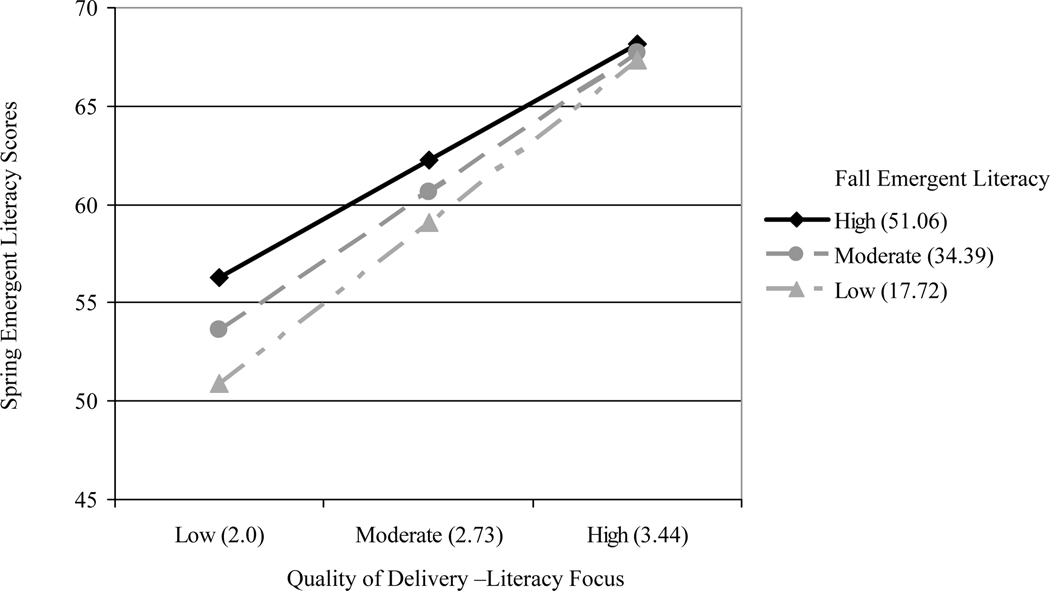

The fourth research question examined whether associations among implementation fidelity and child language and literacy growth may be moderated by child characteristics. Findings indicated that associations between quality of delivery (Language Modeling) and children’s growth in language and literacy skills were contingent on the language spoken in children’s homes. Interactions were graphed following recommendations of Aiken and West (1991) by estimating the level of spring scores (controlling for covariates, including fall scores) for children in classrooms with low, moderate, and high levels of Language Modeling (one SD below mean, mean, and one SD above mean) separately for children with varying language backgrounds. As indicated in Figure 1, there was a stronger association between Language Modeling scores and growth in children’s receptive vocabulary for children whose parents reported speaking a language other than English in the home (B = .95, SE = .43, p < .05) . Furthermore, as displayed in Figure 2, Literacy Focus had a stronger association with growth in emergent literacy composite scores for children who started out the school year with weaker skills in this domain (B = −.07, SE = .02, p < .01) .

Figure 1.

Moderating effects of children’s language background on the association between Language Modeling and children’s receptive vocabulary growth.

Figure 2.

Moderating effects of children’s fall emergent literacy skills on the association between Literacy Focus and children’s growth on the emergent literacy composite.

Discussion

In the context of increasing use of literacy and language curricula in early childhood classrooms (Caswell & He, 2008), it is important to know more about the extent to which early childhood teachers are prepared to deliver these curricula with a high degree of implementation fidelity. It is also necessary to understand whether variations in the quality of implementation influences curricula’s impact on student outcomes. Using three common indicators of fidelity of implementation – dosage, adherence, and quality of delivery – this study suggests that teachers’ fidelity of implementation of one such curriculum – MyTeachingPartner-Language & Literacy (MTP-LL; Justice et al., 2003) – was relatively high in some aspects (dosage, adherence) but relatively low in other aspects (quality of delivery). Importantly, the aspect of fidelity found to be most variable among teachers and that exhibited the lowest “uptake” – namely, quality of delivery – was that aspect of fidelity found to be associated with gains in children’s literacy skills over the preschool year. These findings are consistent with other recent reports (e.g., Caswell & He, 2008; Justice, Mashburn, Pence et al., 2008) suggesting that helping teachers to implement the “active ingredients” of research-based instructional curricula will increase the ultimate effectiveness of these interventions.

Variability in Teachers’ Implementation of Literacy and Language Curricula

The MTP-LL curriculum implemented in this study, like many others available today (see PCER, 2008), includes systematic and explicit instructional activities encompassing prominent domains of language and literacy. MTP-LL activities are guided by research highlighting the importance of providing young children with repeated and explicit exposure to functional literacy and language knowledge and concepts within the context of meaningful activities, such as large-group storybook book reading (Dickinson, Darrow, & Tinubu, 2008; Elley, 1989; Justice et al., 2003; Nash & Donaldson, 2005; Penno et al., 2002). Teachers in this study were asked to deliver six MTP-LL activities each week.

At a basic level, teachers did what they were asked to do in delivering these lessons. Indeed, teachers’ reports at the end of the year suggest that most teachers offered children fairly high dosages of these activities, with teachers reporting spending an average of 100 minutes per week on MTP-LL activities. Each activity was observed to last, on average, 24 minutes. Such findings are similar to those reported in other recent studies of teacher implementation of language and literacy curricula. For instance, Justice et al. (in press) asked preschool teachers to complete implementation logs following each of twice-weekly lesson plans correspondent to a language and literacy curriculum supplement; analysis of submitted logs indicated that teachers reported implemented 80% of lessons over a 30-week period. Such studies indicate that, in general, teachers will deliver curricular lessons at suggested dosage rates. Interestingly, the two measures of dosage were not associated with one another. It is possible that teachers who tended to conduct lessons for longer were not the same teachers who conducted the lessons more frequently. Alternately, it may be that teachers’ end-of-year ratings of dosage are too imprecise to sufficiently capture range in dosage.

Adherence findings exhibit similar trends. Based on observational ratings, teachers adhered fairly well to the lessons. For example, teacher’s language was in general accordance with the activity scripts an average of 93% of the time, and they used all listed materials in accordance with the activity plan 79% of the time. This finding indicates that teachers will follow suggested plans and scripts with appropriate levels of attention to procedural details. Yet, as results of this study show, we have limited evidence that high levels of dosage and adherence are the aspects of fidelity that matter most when considering the effectiveness of curricula for improving children’s learning.

It was the third aspect of implementation fidelity examined in this study, quality of delivery, which exhibited links to child outcomes as well as the lowest levels of implementation fidelity. Although there is no clear consensus in the literature on how best to define and measure quality of delivery as a feature of implementation in fidelity, it is generally described as comprising the interactive aspects of delivery of activities (Greenberg et al., 2005; O’Donnell, 2008). The present study captured quality of delivery through assessments of the degree to which teachers used empirically-based teaching strategies in their instruction of literacy and language skills. Using this definition suggests that quality of delivery goes above and beyond simple adherence to a particular lesson to assess the degree to which teachers effectively implement interactive instructional strategies known to facilitate children’s early literacy and language skills.

More specifically, to capture quality of delivery, trained observers used two scales from the CLASS to assess the quality of implementation of activities with respect to language facilitation (Language Modeling) and literacy instruction (Literacy Focus) during the MTP-LL activities. Language Modeling assesses the degree to which teachers use strategies that facilitate teacher-child discussion and increasingly complex language use by children (e.g., repetition, extension, self-talk, advanced vocabulary) and is scored from one to seven, with one representing limited use of these language strategies and seven representing high use of these strategies. Activities in this study received an average score of 2.73 on Language Modeling, suggesting that fairly low levels of quality language instruction are occurring during teachers’ implementation of activities within the literacy and language curriculum.

Literacy Focus assesses the degree to which teachers explicitly direct children’s attention to code-based aspects of oral and written language, as well as the degree to which these interactions are embedded in meaningful activities for children (e.g., generation of a shopping list vs. use of flashcards). Like Language Modeling, Literacy Focus is scored on a one to seven scale, with one representing the absence of these features of literacy instruction and seven representing consistent and explicit exposure to these features of literacy instruction across the activity implementation. The average Literacy Focus score applied to MTP-LL activities, as observed across the school year, was 2.5. Thus, it appears that teachers do not generally exhibit high quality of service delivery when delivering language and literacy activities.

An important caveat in this description of quality of delivery concerns the scaling of the CLASS measure. Given the low scores reported here and similarly low scores on the other Instructional Support dimensions of CLASS in other studies (Pianta et al., 2005), it may be that the high end of the CLASS scales set unreasonable expectations for early childhood classrooms. At the high end the types of interactions described in these scales are observed consistently. It is possible that even less frequent exposure to these explicit interactions (as indicated by scores in the low-mid or mid range) may be sufficient to produce positive outcomes. One recent study suggests that the higher scores on the CLASS Instructional Support dimensions (Concept Development and Quality of Feedback) predict language and math outcomes even within the low to low-mid range (Burchinal, Vandergrift, Pianta, & Mashburn, 2008). Thus, for example, a classroom scoring at just a three on these scales may offer significant advantages over a classroom scoring a 1 or 2. Further research on issues of thresholds of quality, using CLASS and other measures, is warranted.

Nevertheless, these findings related to the low level of quality of literacy and language instruction are consistent with work using the other measures (e.g., Hindman, Connor, Jewkes, & Morrison, 2008; Podhajski & Nathan, 2005; PCER, 2008; Rowell, 1998) and provide further evidence that despite significant gains in our knowledge of effective teaching practices, teachers do not consistently use these practices when working with young children, even in the context of delivering a literacy and language curriculum. For example, one recent study found that early childhood teachers focused on code-related talk during shared book readings an average of only five times during a typical book reading (Hindman et al., 2008) and that teachers used this kind of talk even less frequently than did parents. Such findings also suggest the importance of conceptualizing implementation fidelity using a multi-dimensional lens that disentangles more procedural aspects of fidelity – dosage and adherence – from quality of delivery.

This point raises an important question regarding whether the degree to which quality of delivery, as we have defined it in this work, is a “fair” measure of implementation fidelity. In other words, if teachers adhered to the activity scripts and implement lessons at recommended dosages how could they score so low on these measures of quality of delivery? Data from this study suggest that measures of adherence, dosage, and quality of delivery are not associated with one another. The MTP-LL activities provided fairly detailed guidelines for teachers, and included suggestions around language (questions to ask, etc) but they were not fully scripted (see Appendix A). Thus, they left teachers with significant freedom to decide how to actually implement the activities in terms of the instructional interactions that take place within the lesson structures. Given that quality of delivery, as defined here, captures interactive processes between teachers and children, it is challenging to provide supports to teachers in this area solely based on written instructions to teachers. As discussed in greater detail below, there is a need to further study the best ways for curriculum developers to embed supports for high quality of delivery within activities themselves, as well as to provide additional supports to teachers to enhance the quality of their interactions with children during activity implementation.

In reference to this point, it is important to note that low levels of quality in teachers’ delivery of language and literacy activities was apparent despite the fact that all teachers in this study had a bachelor’s degree and were, on average, very experienced teachers. Previous work suggests that factors such as degree status and experience are not typically strong indictors of the quality of interactions that teachers have with young children (Early et al., 2007; Justice, Mashburn, Hamre et al., 2008; Mashburn et al., 2008) or their beliefs about effective teaching practices (Hindman & Wasik, 2008). Thus, it is apparent that interventions intended to improve children’s literacy and language achievements in preschool settings must give significant attention to the skills of teachers when delivering curricula, regardless of teachers’ education.

Linking Implementation Fidelity to Child Outcomes

A large body of work in public health and prevention research (e.g., Dusenbury et al., 2003; Greenberg et al., 2005) suggests that variability in implementation fidelity is important. However, there are few examples of research connecting implementation to student outcomes within the early childhood field (exceptions are Clements & Sarama, 2008; Justice, Mashburn, Pence et al., 2008). The present study advances this field of study and provides evidence that both dosage and quality of delivery are associated with child outcomes in early childhood settings. Findings for dosage were not particularly strong; only one measure of dosage (observed rather than reported) was related to one of the four outcome measures. Adherence was not related to children growth in any of the assessed skills. The lack of findings in this regard may relate to the way in which dosage and adherence data were collected for this study, a point we return to shortly. Nonetheless, findings did show that one aspect of fidelity, specifically teachers’ delivery of activities, was consistently related to growth in children’s emergent literacy and language skills.

Children in classrooms in which teachers provided higher quality of delivery, in the form of more consistent and explicit exposure to literacy concepts and knowledge, showed greater growth in print awareness and the emergent literacy composite over the course of the preschool year. Furthermore, quality of delivery appeared to matter more for certain subsets of children. Consistent with the work of Connor and others (e.g., Connor et al., 2004; Morrison & Connor, 2002), children who entered preschool with the lowest skills on the emergent literacy composite were most likely to benefit from the provision of higher quality explicit literacy instruction during the implementation of MTP-LL activities. Similarly, children who did not speak English at home benefited the most from classrooms in which teachers provided higher quality language facilitation during the implementation of MTP-LL activities. Although there is a wealth of descriptive data on the types of experiences young ELL children experience in school (e.g. Tabors, 1997) as well as consistent evidence pointing to the need to deliver instruction in children’s native language (Barnett, Yarosz, Thomas, Jung, & Blanco, 2007; Restrepo & Dubasik, 2008; Rodriguez, Diaz, Duran, & Espinosa, 1995), there is much less empirical evidence regarding the particular types of instructional strategies that are most effective for facilitating language and literacy growth among preschool ELL children (Downer et al., 2009). The results presented here provide initial data to suggest that the types of language instructional strategies identified as effective in the more general population are also effective for this subset of children.

One important question concerns the degree to which these effects for Literacy Focus and Language Modeling are specific to the curriculum, versus representing more generalized effects of use of these types of instructional practices across the school day. We expect that the finding represents both processes. The MTP-LL activities were designed to enhance teachers’ use of these strategies, although clearly the results suggest there is room for improvement. Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, et al. (2008) provide some evidence for the ways in which use of activities may drive practices. In that study teachers were observed to have higher Literacy Focus scores when implementing one of the MTP-LL Literacy activities and higher Language Modeling scores when implementing one of the Language activities over the first months of MTP-LL implementation. Parallel analyses were not possible in the present study because we examined composite scores across a variety of Language and Literacy activities; however given that the current study followed the same group of teachers as did the Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, et al. (2008) study, we anticipate the results would have been similar. A more accurate assessment of this question would require examination of teachers using MTP-LL versus other curricula or more generalized practices, data that were not available in the current study.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study warrant note. First, the findings should not be generalized beyond the current sample of state pre-k teachers who agreed to participate in an intervention research study and who at least minimally complied with requests for data by sending in at least one videotape. All of the teachers in this sample had bachelor’s degrees and most were experienced teachers; replication with a broader representation of early childhood teachers is warranted.

The failure to find consistent positive effects of dosage and adherence may be the result of the study design or limitations of those measures. The MTP study was not designed as an overall test of the efficacy of the MTP curricula, but rather a test of the supports offered to accompany the curricula. There is not yet efficacy data on the MTP-LL curricula, thus the limited findings on dosage and adherence could be suggestive that the curricula itself is not effective. The finding that teachers who conducted longer lessons had students who made greater gains is suggestive of positive effects; nevertheless future work should more explicitly examine the efficacy of this curriculum. With regard to the potential limitations of the measures, the teacher-report version of dosage was unrelated to outcomes while the more objective assessment of dosage, observations of length of activities, was related to gains in children emergent literacy skills. This finding underscores the importance of using objective measures of implementation when possible. With regards to the adherence measure, limited variance and ceiling effects may have reduced associations with outcome variables. This measure was designed to be applied to both the MTP-LL and PATHS curricula, thus limiting its specificity to either curricula and reducing its ability to accurately assess adherence specifically for MTP-LL.

A final possibility for the limited findings for some aspects of implementation relates to the extent to which it is appropriate to generalize findings based on a few video samples of activities. Teachers had, on average, 4.5 videos coded for implementation fidelity purposes across the year. This is a small sampling of behavior which may have been further limited by the fact that these were a mix of lessons – some focused on literacy and some on language. Given that previous research shows that the content of the lesson may influence Language Modeling and Literacy Focus scores (Justice, Mashburn et al., 2008), results may have been somewhat biased. Other work has suggested that relatively small samplings of teacher behavior are predictive of general practice (Chomat-Mooney et al., 2008); however, future work should more systematically address these issues with respect to implementation fidelity.

In general effects sizes were small. This is likely a reflection of a variety of factors, including error associated with teacher-assessed outcomes which likely limited the precision with which we were able to assess student’s academic performance. We also did not gather information on what teachers did with children, in terms of implementation of the MTP-LL curriculum or more generalized practice, outside of the 30-minute videotapes they sent to the research team. Live observations, across several school days, in which these same measures were coded would provide a much richer description of the context in which these children learned early literacy and language skills and allow us to more systematically assess the degree to which the findings for quality of delivery were primarily the result of the use of MTP-LL or more generalized practice.

Another limitation concerns findings regarding the influence of quality of implementation on English Language Learners. In this study, we did not collect detailed information about the language of instruction used in children’s classrooms. In general, the vast majority of instruction in these classrooms was provided in English. However, there were cases when the lead teacher or assistant teacher may have provided some instruction in Spanish, but this was not coded as a part of the current project. We expect that more information about the language environment would help us better understand the ways in which specific types of instructional strategies may facilitate literacy and language development for ELL children. Understanding how individual differences among children may influence the effectiveness of various language and literacy curricula in use today is an important direction for future research.

Implications

Findings that quality of delivery of a systematic classroom language and literacy curriculum was a significant predictor of children’s growth in early literacy and language skills, coupled with evidence that quality of delivery was fairly low in this sample of pre-k teachers, may help explain mixed findings related to the efficacy of literacy and language (and other) curricula in early childhood settings (e.g., Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research Consortium, 2008). Consistent with work in prevention science (Greenberg et al., 2005), interventions are unlikely to have strong effects without very careful attention directed to the way in which the interventions are actually delivered in classrooms.

One implication of these findings relates to the kinds of supports that can be provided to teachers to improve their implementation of curriculum, with a specific focus on improving the ways in which they make use of empirically based teaching strategies. Supports for teachers may come as a part of the activity itself, such as the use of scripting which actually embeds these types of instructional conversations into the activity plans. However, the results of this study suggest that teacher adherence to lesson scripts is not necessarily associated with more frequent use of content-specific instructional practices. Therefore, curriculum developers need to attend to other ways to support teachers’ use of these practices.

Because the quality of delivery is an interactive process, supports intended to improve this aspect of implementation are likely to require approaches that are more intensive and ongoing than the typical one-day introductory workshop (Justice, Mashburn, Hamre et al., 2008). There is now ample research suggesting that these practices are amenable to change if the supports provided to teachers are fairly intensive (Caswell & He, 2008; Klein & Gomby, 2008; Landry et al., 2006; Pence, Justice, & Wiggins, 2008). Dickinson and Caswell (2007), for instance, showed that teachers participating in a four-unit course (delivered in two three-day intensive sessions) showed more positive growth on a comprehensive observational measure of language and literacy instruction within their classrooms than did teachers who did not take the course. Similarly, Domitrovich and colleagues found that teachers receiving four days of training along with weekly in-class support from a mentor teacher showed positive growth relative to a control group in the extent to which they talked with children in cognitively complex ways (Domitrovich et al., in press).

The curriculum used by teachers in the present study, MTP-LL, was designed, in part, to be coupled with additional supports available to teachers to support their growth in more interactive aspects of teaching; research on the effects of these supports are described in detail elsewhere (Mashburn et al., 2008; Pianta, Downer, et al., 2008). About half of the teachers in the sample received access to a website that provided video exemplars of effective teaching strategies (see Downer, Kraft-Sayre et al., in press for a description of these supports and teachers’ use of them), whereas the other half were provided with access to these video resources as well as to ongoing, web-based consultation to improve the quality of the implementation of these activities. Pianta, Downer, et al. (2008) describe the ways in which these supports, particularly the consultation, were associated with more positive improvements in the quality of teacher-child interactions over the course of the year. Most relevant to the current study, teachers in the consultation improved in their Language Modeling scores from CLASS across the first year of the intervention. Additionally, students of teachers who fully participated in the consultation made greater progress in early literacy and language skills across the preschool year (Mashburn et al., 2008). Thus, consistent with a recent synthesis of professional development in early childhood (Klein & Gomby, 2008), provision of intensive, personalized supports may be important to ensuring high quality of delivery of curricular innovations within the early childhood sector. That said, the current study suggests that even given those types of supports, the quality of teacher-child interactions focused on language and literacy development during the implementation of the MTP-LL curriculum is quite variable and lower than we would hope. This is likely a function of the fact that not all teachers used these supports consistently (Downer, Hamre, et al., in press; Downer, Kraft-Sayre, et al., in press) as well as the fact that most teachers started out the year quite low on these aspects of their instruction (Justice, Mashburn, Hamre et al., 2008).