Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias, with millions of patients afflicted worldwide. To develop more effective therapies for AF, it is essential to comprehend its underlying mechanisms. Large animal arrhythmia models are more similar to humans in terms of atrial anatomy and cellular electrophysiology, but their availability, cost and reliance on pharmacological probes of limited mechanistic specificity are big drawbacks. Mouse models have several advantages, including ease of genetic manipulation to mimic clinical changes and affordable phenotyping platforms.1

Studies were performed on patients with paroxysmal-AF (pAF) and controls in sinus rhythm (SR) with approval of the South Central-Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee (UK-18/SC/0404) and the University of Duisburg-Essen Human Ethics Committee (AZ-12-5268-BO). Patients gave informed written consent and underwent coronary artery bypass grafting or valve repair/replacement in the John Radcliffe hospital (Oxford, UK) or the West German Heart Center at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Average age of patients in SR was 70.0 (interquartile range 63.0±75.5) vs 69.0 (IQR 61.5±73) years for patients in pAF; 82% were male (both SR and pAF), with similar left ventricular ejection fractions (LVEF) of 58.8±9.5% (SR) vs 56.4±6.7% (pAF). There were no differences in medical history (i.e., hypertension, prior myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, or smoking).

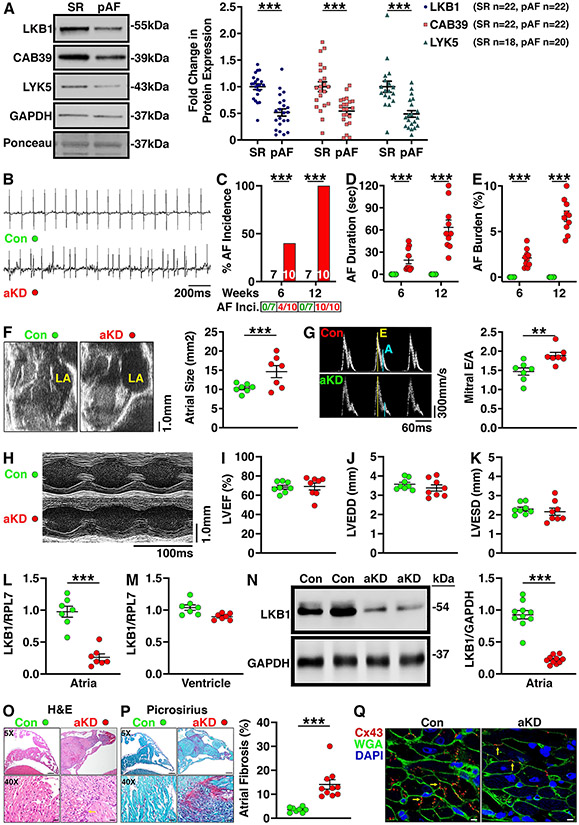

Western blotting of right-atrial biopsies revealed downregulated protein expression of liver kinase-B1 (LKB1) and its binding partners CAB39 and STRAD (LYK5) in pAF patients compared with controls (Fig. 1A). LKB1 acts as a master upstream kinase, directly phosphorylating and activating AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and several other kinases that have various roles in cellular physiology and metabolism.2 Prior studies revealed that whole-heart, cardiomyocyte-specific LKB1 knockout mice develop spontaneous AF by 8 weeks of age.2 However, a major limitation of this model is that these mice also develop ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure, complicating mechanistic studies because of the confounding effects of ventricular dysfunction on AF.3 To overcome this constraint, we utilized an adeno-associated viral (AAV9) vector containing a modified ANF promoter to produce atrial-specific gene alterations.4 Specifically, we used the AAV9-ANF-Cre vector (5x1011 genome copies) to drive atrial-specific LKB1-knockdown (LKB1-aKD) following injection into 5-day-old LKB1FL/FL mice. All animal studies were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine IACUC.

Figure 1.

A) Representative Western blot images and quantification showing the protein expression levels of LKB1, CAB39, and LYK5 in right-atrial appendage samples from patients with paroxysmal AF (pAF; n=22) vs controls in sinus rhythm (SR; n=22). Data are expressed as fold change of the respective controls in SR vs GAPDH. B) Representative telemetry ECG tracings in 8-week-old LKB1FL/FL mice that received AAV9-ANF-mCherry (control mice; Con; n=7) or AAV9-ANF-Cre vector to induce atrial-specific knockdown of LKB1 (aKD; n=10). ECG tracings show sinus rhythm in the control mouse and an episode of spontaneous AF in the LKB1-aKD mouse, respectively. Summary graphs showing AF incidence (number of mice positive for AF divided by total number of mice tested is shown below the bars; C), duration of the longest AF episode (D), and burden of AF (defined as time in AF divided by total time period analyzed, including 1 hour at nighttime and 1 hour during daytime), (E) at 6 and 12 weeks in control and LKB1-aKD mice. F) Representative B-mode echocardiogram images and interleaved scatter plots showing increased atrial size in LKB1-aKD (n=7) vs control mice (n=7). G) Doppler recordings showing mitral valve flow and quantification of the E/A ratios in 12-week-old control (n=7) and LKB1-aKD mice (n=7) revealing increased mitral valve E/A (MVE/A) ratios in LKB1-aKDA mice. H) Representative M-mode echocardiograms of the left ventricle (LV) of control and LKB1-aKD mice. Interleaved scatter plots showing I) preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), J) unaltered LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and K) unaltered LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD) in 12-week-old LKB1-aKD mice (n=8) compared with controls (n=8). L-M) Summary scatter plots showing expression of LKB1 mRNA (normalized to RPL7) in atria (L) and ventricles (M) of LKB1-aKD (n=7) and control mice (n=7). N) Representative western blot images and quantification showing reduced LKB1 protein expression levels in atrial tissues from LKB1-aKD (n=10) vs control mice (n=10). O) Representative images of H&E staining (left) showing cellular infiltration (arrow) in atria of LKB1-aKD (n=10) vs control mice (n=8). P) Representative images of Picrosirius red staining (left) and quantification of interstitial fibrosis (right) of atrial sections from LKB1-aKD (n=10) vs control mice (n=8). Q) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining showing Cx43 (red; arrows), WGA (green) and DAPI (blue) in atrial sections from LKB1-aKD vs control mice. Data are represented as average±SEM. P values were determined by unpaired Mann-Whitney test (panels A, D, E, F, G, L, M, N, and P), Fisher's exact test (C). **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

ECG telemeters were implanted subcutaneously at 4-weeks of age. After a 2-week recovery period, continuous 24 hour ECGs were recorded once a week between 6-12 weeks of age. Episodes of AF were defined based on a lack of P-waves and irregularly irregular R-R intervals for more than 10 seconds (Fig. 1B). LKB1-aKD mice exhibited an age-dependent increase in the incidence (Fig. 1C), duration (Fig. 1D), and burden (Fig. 1E) of spontaneous AF episodes. Echocardiography revealed a 1.5±0.3-fold increased atrial size in LKB1-aKD mice (Fig. 1F). Moreover, Doppler echocardiography revealed a diminished A-wave and hence increased E/A ratio across the mitral valve in LKB1-aKD mice, indicative of impaired atrial contraction (Fig. 1G). Whereas whole-heart LKB1-knockout mice exhibit ventricular failure at 8 weeks-of-age,3 echocardiography (Fig. 1H) revealed normal left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction, end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions in 12 week-old LKB1-aKD mice (Fig. 1I-K).

Atrial tissues were obtained from 12 week-old LKB1-aKD and control mice. qRT-PCR analysis revealed a 73.2±5.0% reduction of LKB1 mRNA levels in atria of LKB1-aKD mice (Fig. 1L), whereas ventricular LKB1 mRNA levels were unaltered (Fig. 1M). Western blotting revealed a significant downregulation of LKB1 protein levels (by 76.1±2.0%) in atria of LKB1-aKD mice (Fig. 1N), consistent with atrial-specific LKB1 knockdown. H&E staining of atrial tissue sections revealed increased immune-cell infiltration (Fig. 1O). Moreover, Picrosirius-red staining showed a 14.1±1.9% collagen content in atria of LKB1-aKD mice compared with 3.5±0.3% in control mice (P<0.001), indicating increased levels of interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 1P). Finally, immunofluorescence staining revealed reduced expression levels (by 30.4±2.8%) and intercellular redistribution of connexin-43 (Cx43) in left-atrial tissue from LKB1-aKD mice (Fig. 1Q).

Our findings demonstrate that AAV9-mediated atrial myocyte-restricted knockdown of LKB1 produces a novel mouse model of atrial cardiomyopathy with spontaneous AF without molecular or phenotypic alterations in the ventricles. This model appears to be clinically relevant as patients with pAF exhibited reduced LKB1 expression levels. Moreover, LKB1-aKD mice develop spontaneous AF, interstitial fibrosis, atrial dilation and impaired atrial function, all hallmarks of atrial cardiomyopathy.5 While the focus of this study was not on downstream effects of LKB1, this kinase directly phosphorylates and activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and appears to play a role in cellular energy metabolism. While there are substantial differences between atrial size and electrophysiology comparing mice and humans, mice can be a very useful animal model due to the ease of genetic manipulation and low costs compared to large animal models. Thus, LKB1-aKD mice represent a practical atrial-specific mouse model of atrial cardiomyopathy with spontaneous AF, well suited for mechanistic studies aimed to uncovering the molecular basis of spontaneous AF without confounding influences from ventricular remodeling. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, according to Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) guidelines.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was performed during MH’s tenure as “The Kenneth M. Rosen Fellowship in Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology” Fellow of the Heart Rhythm Society supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Medtronic. S.L. was supported by an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship. DD was funded by NIH grants R01-HL131517, R01-HL136389, and R01-HL089598, and the German Research Foundation (DFG) grant Do 769/4-1, and the European Union (large-scale integrative project MEASTRIA, No. 965286). S.N. was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. S.R. was supported by the British Heart Foundation Intermediate Research Fellowship (FS/16/5/32054). XW was funded through NIH grants HL089598, HL091947, HL117641, and HL147108, and the Quigley Endowed Chair in Cardiology.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERERENCES

- 1.Dobrev D and Wehrens XHT. Mouse Models of Cardiac Arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2018;123:332–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozcan C, Battaglia E, Young R and Suzuki G. LKB1 knockout mouse develops spontaneous atrial fibrillation and provides mechanistic insights into human disease process. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda Y, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Sam F, Shaw RJ, Dyck JR and Walsh K. Cardiac-specific deletion of LKB1 leads to hypertrophy and dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35839–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni L, Scott L Jr., Campbell HM, Pan X, Alsina KM, Reynolds J, Philippen LE, Hulsurkar M, Lagor WR, Li N and Wehrens XHT. Atrial-Specific Gene Delivery Using an Adeno-Associated Viral Vector. Circ Res. 2019;124:256–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goette A, Kalman JM, Aguinaga L, Akar J, Cabrera JA, Chen SA, Chugh SS, Corradi D, D'Avila A, Dobrev D, Fenelon G, Gonzalez M, Hatem SN, Helm R, Hindricks G, Ho SY, Hoit B, Jalife J, Kim YH, Lip GY, Ma CS, Marcus GM, Murray K, Nogami A, Sanders P, Uribe W, Van Wagoner DR and Nattel S. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: Definition, characterization, and clinical implication. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:e3–e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]