Abstract

Background

Spain introduced the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in the childhood National Immunization Program in 2015–2016 with coverage of 3 doses of 94.8% in 2018. We assessed the evolution of all pneumococcal, PCV13 vaccine type (VT), and experimental PCV20-VT (PCV13 + serotypes 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 22F, 33F) hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in adults in Spain from 2011–2018.

Methods

A prospective observational study of immunocompetent adults (≥18 years) admitted to 4 Spanish hospitals with chest X-ray–confirmed CAP between November 2011 and November 2018. Microbiological confirmation was obtained using the Pfizer serotype-specific urinary antigen detection tests (UAD1/UAD2), BinaxNow test for urine, and conventional cultures of blood, pleural fluid, and high-quality sputum.

Results

Of 3107 adults hospitalized with CAP, 1943 were ≥65 years. Underlying conditions were present in 87% (n = 2704) of the participants. Among all patients, 895 (28.8%) had pneumococcal CAP and 439 (14.1%) had PCV13-VT CAP, decreasing from 17.9% (n = 77) to 13.2% (n = 68) from 2011–2012 to 2017–2018 (P = .049). PCV20-VT CAP occurred in 243 (23.8%) of those included in 2016–2018. The most identified serotypes were 3 and 8. Serotype 3 accounted for 6.9% (n = 215) of CAP cases, remaining stable during the study period, and was associated with disease severity.

Conclusions

PCV13-VT caused a substantial proportion of CAP in Spanish immunocompetent adults 8 years after introduction of childhood PCV13 immunization. Improving direct PCV13 coverage of targeted adult populations could further reduce PCV13-VT burden, a benefit that could be increased further if PCV20 is licensed and implemented.

Keywords: community-acquired pneumonia, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, pneumococcal pneumonia, PCV13 serotypes

Serotypes included in PCV13 caused 14% of hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) in immunocompetent adults in Spain 8 years after introduction of PCV13 childhood immunization. Direct vaccination with PCV13 currently and with extended spectrum vaccines in the future may help address CAP burden among adult populations.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Grijalva on pages 1086–8.)

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. It mainly affects adults aged 65 years and older, with increased risk in immunocompromised individuals and those with underlying comorbid conditions such as chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, diabetes, and high alcohol intake [2]. In adults, noninvasive pneumococcal pneumonia is responsible for most CAP burden, while invasive pneumonia accounts for less than 10% of the cases [3].

In Spain, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have demonstrated substantial effectiveness in reducing pneumococcal disease due to vaccine serotypes [4]. The 13-valent PCV (PCV13) that includes serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 19A, and 23F was introduced by Spain in 2010 for immunization of healthy children mainly through the private market [5]. Madrid (June 2010) [6] and Galicia (January 2011) [7] regions had publicly funded National Immunization Programs (NIPs), which were expanded nationally in 2015–2016 [8] with a 2 + 1 schedule. In 2018, the coverage of the booster dose reached 94.8% [9]. For adults, the current Spanish vaccination policy recommends PCV13 followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPV23) for high-risk adults aged 18 years or older, PPV23 for those older than 2 years who are at risk due to underlying conditions [10], and PPV23 as the preferred pneumococcal vaccine for all adults aged 65 years and older [11]. Nationally, PPV23 uptake for persons older than 60–65 years in Spain was 43.8% during 2013–2014 [12]. During 2016–2019, 6 regions (Madrid, Galicia, Castilla and Leon, La Rioja, Asturias, and Andalucia) [13–18] have included in their immunization programs PCV13 for adults older than 18 years who are at risk based on underlying conditions and for adults older than 60–65 years. For the current study, only 1 of the hospitals was in a region (Galicia) that recommends PCV13 for adults aged 65 years. This recommendation has existed as of 2017 [17]. Supplementary Table 1 shows recommendations on pneumococcal vaccination for adults in the regions where the study was conducted.

PCV13 use in childhood NIPs has been associated with rapid and sustained reductions in overall and vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPDs) in young children and unvaccinated older age cohorts [19]. However, recent reports indicate that the indirect effects have plateaued in many geographic regions, even those with high coverage, and primarily for serotypes 3, 7F, 19A, and 19F [20]. In fact, a previous study on the burden of PCV13 serotypes in Spanish adults showed an insufficient indirect protection from childhood vaccination [21]. One potential solution is direct immunization of adults, since in a randomized controlled trial of older Dutch adults, PCV13 demonstrated efficacy against primarily nonbacteremic CAP due to serotypes 3, 7F, and 19A (too few 19F cases occurred to assess efficacy) [22]. To inform this decision, and for decisions regarding adult use of extended future PCVs, it is critical to understand the serotype distribution of pneumococcal CAP in particular locales.

From 2011 to 2018, we conducted an observational, multicenter, prospective, hospital-based study to determine the contribution of specific serotypes to CAP in immunocompetent adults by using serotype-specific urinary antigen detection tests (UAD1/UAD2). The study included serotype-specific contribution to disease severity, evolution, and associated comorbidities after the introduction of PCV13 in children.

METHODS

Participants

Between November 2011 and November 2018 immunocompetent adults aged 18 years or older prospectively admitted with CAP to the following 4 tertiary-care hospitals from the National Spanish Health System were included in the study (patients included in each hospital): Hospital Clinic i Provincial, Barcelona (Catalonia) (total number of included CAP, n = 610; 19.6% of all CAP cases); Hospital La Fe, Valencia (Valencia) (1012; 32.6%); Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia (Basque country) (1020; 32.8%); and Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Pontevedra (Galicia) (465; 15.0%). Inclusion criteria are detailed in the Supplementary Material. The ethics committee at each hospital approved the study and patients provided written informed consent.

As per standard clinical practice, data were recorded on age, gender, underlying conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney failure, asthma, diabetes mellitus, chronic heart failure, chronic liver disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer), alcohol consumption, tobacco cigarette smoking, history of previous pneumonia, history of hospitalization for at least 48 hours within the 2 weeks prior to current admission, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccination history. The CURB-65 score, Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), and the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) minor criteria were used to evaluate severity on hospital admission. The evolution and outcome were also recorded.

Microbiological Studies

Microbiological tests were performed at each participating hospital according to standard clinical practice and based on clinical judgment of the attending physician. Cultures were performed on available samples from blood (n = 2120), pleural fluid (n = 231), and on high-quality sputum samples (<10 epithelial cells and >25 leukocytes per field; magnification ×100) (n = 1186). Sputum cultures with unique or abundant Streptococcus pneumoniae growth and compatible Gram staining were considered as positive for pneumococcus. The BinaxNow S. pneumoniae Urinary Antigen Test (n = 2921) and BinaxNow Legionella pneumophila Urinary Antigen Test (n = 2921) were used. Other diagnostic tests (n = 724) were performed if indicated by the attending physician and included polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viruses and serological studies for the detection of antibodies to Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetii, and L. pneumophila. The Pfizer serotype-specific urinary antigen detection tests UAD1, detecting PCV13 serotypes (from 2011), and UAD2, detecting serotypes 2, 8, 9N, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 17F, 20, 22F, and 33F (starting in 2016), were performed for urine samples from all patients (N = 3107). Serotyping was also performed on isolates from blood or pleural fluid cultures. Isolates and urine samples were processed as described in the Supplementary Material.

Definitions

Pneumococcal CAP was defined as chest X-ray (CXR)–confirmed CAP with a positive result from any microbiological test for S. pneumoniae (BinaxNow test, UAD test, blood culture, pleural culture, and sputum culture). The CXR confirmation was based on clinician judgment. Invasive pneumococcal CAP was defined as isolation of S. pneumoniae from blood or pleural fluid. Noninvasive pneumococcal CAP was defined as pneumococcal CAP excluding invasive pneumococcal CAP. Pneumococcal serotypes were categorized as follows—PCV13-VT: 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F; 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, 19A; PCV15: PCV13-VT plus 22F and 33F; and PCV20: PCV15-VT plus 8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15 B/C. Clinical characteristics defining complicated CAP are described in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using EPIDAT 3.0 and SPSS 26.0 (IBM SPSS) software. For comparisons of independent samples, the Pearson chi-square test (or the Fisher’s exact test for 2 × 2 tables or likelihood ratio for M × N tables, as appropriate) was used for qualitative variables and Student’s t test, single-factor ANOVA (or its nonparametric equivalent Mann-Whitney U test), and Kruskal-Wallis H test for quantitative variables were used. Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of the variables were studied for use of parametric tests. In order to find a measure of association between the serotypes causing pneumococcal pneumonia and its severity (CURB-65, PSI, complication of pneumonia, sepsis and/or septic shock, and admission to the intensive care unit [ICU]), a univariate logistic regression model was conducted with severity as a dependent variable and identified serotypes (culture as the “gold standard”) as independent variables.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 3107 patients were recruited from November 2011 to November 2018 (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Their mean age was 66.83 ± 17.25 years, and 61.5% were male. Eighty-seven percent of patients with CAP had at least 1 underlying condition or risk habit. Streptococcus pneumoniae was identified in 895 patients (28.8%). Among these pneumococcal pneumonia cases, 149 (16.6%) were invasive and 746 (83.4%) were noninvasive. Other frequently detected micro-organisms are described in Supplementary Figure 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population in the Whole Cohort and in Pneumococcal Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| All-Cause CAP (n = 3107) | Pneumococcal CAP (n = 895)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–64 y | 1164 (37.5) | 326 (36.4) |

| ≥ 65 y | 1943 (62.5) | 569 (63.6) |

| Mean ± SD, y | 66.8 ± 17.2 | 67.3 ± 16.8 |

| Male gender | 1283 (61.5) | 540 (60.3) |

| One or more underlying condition | 2704 (87.0) | 773 (86.4) |

| COPD | 583 (18.8) | 172 (19.2) |

| Chronic heart failure | 337 (10.8) | 78 (8.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 714 (23.0) | 178 (19.9) |

| Chronic liver disease | 104 (3.3) | 33 (3.7) |

| Chronic renal failure | 297 (9.6) | 74 (8.3) |

| Stroke | 250 (8.0) | 72 (8.0) |

| Asthma | 271 (8.7) | 86 (9.6) |

| Cured neoplasia | 327 (10.5) | 104 (11.6) |

| Previous hospitalization | 91 (2.9) | 28 (3.1) |

| Previous pneumonia | 571 (18.4) | 159 (17.8) |

| Tobacco cigarette smokingb | 553 (17.8) | 169 (18.9) |

| Alcoholismc | 114 (3.7) | 38 (4.2) |

| Vaccination history | ||

| Influenza vaccine | 1547 (49.8) | 434 (48.5) |

| Pneumococcal vaccined | 441 (14.2) | 104 (11.6) |

| PPV23e | 376 (85.3) | 89 (85.6) |

| 18–64 y | 40 (10.6) | 6 (6.7) |

| ≥ 65 y | 336 (89.4) | 83 (93.3) |

| PCV13f | 43 (9.8) | 11 (10.6) |

| 18–64 y | 5 (11.6) | 2 (18.2) |

| ≥65 y | 38 (88.4) | 9 (81.8) |

| Both | 11 (2.5) | 2 (1.9) |

| 18–64 y | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ≥65 y | 11 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Severity | ||

| PSI score IV–V | 1250 (40.6) | 395 (44.4) |

| CURB-65 risk score 3–5 | 401 (13.8) | 148 (17.5) |

| ≥3 IDSA/ATS minor criteria for severe CAP | 299 (9.6) | 114 (12.7) |

| Outcomes | ||

| ICU admission | 313 (10.1) | 119 (13.3) |

| Inpatient mortality | 81 (2.6) | 22 (2.5) |

| 30-Day mortality (after discharge) | 10 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CURB 65, Score for Pneumonia Severity: Confusion, BUN > 19 mg/dL (>7 mmol/L), Respiratory Rate ≥ 30, Systolic BP < 90 mmHg or Diastolic BP ≤ 60 mmHg, Age ≥ 65; ICU, intensive care unit; IDSA/ATS, Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society; PSI, Pneumonia Severity Index.

aPolymicrobial etiology: 12.3% of the cases. Influenza virus was the most frequently identified agent in the pneumococcal cases.

bTobacco cigarette smoking: smokers of ≥10 cigarettes per day within the previous year or quitting smoking less than 6 months before.

cAlcoholism: intake ≥80 g/day during at least the previous year.

dOnly 2 patients received a pneumococcal vaccine in the 30 days before to be included in the study.

e23-Valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 20, 22F, 23F, 33F serotypes).

f13-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 23F serotypes).

Complications, Length of Stay, and Outcome

During hospitalization, 1002 patients (32.2%) had complications. Among the 298 complicated cases of pneumococcal pneumonia, sepsis and septic shock were present in 10.5% and 12.5%, respectively. The mean length of hospital stay was 8.8 days (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.5–9.1 days) and the mean length of ICU stay among those in the ICU was 8.5 days (95% CI: 7.5–9.6 days). Case fatality rates were 3.0% for all-cause CAP.

Pneumococcal Serotypes Evolution and Distribution According to Age and Comorbidities

Pneumococcal serotype was identified in 617 patients by UAD1/UAD2 tests or culture. Six isolates of invasive pneumococcal pneumonias were not serotyped due to lack of sample or lysis. Overall, the percentage of all-cause CAP cases due to PCV13 serotypes decreased significantly (P = .049) from 17.9% in 2011–2012 to 13.2% in 2017–2018. However, an increased trend was noted from 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 (from 9% to 13.2%; P = .773) (Table 2). The proportion of all-cause CAP due to PCV20 serotypes remained stable (~24%) from 2016 through 2018 (UAD2 was not available before 2016 and thus data on PCV15 and PCV20 coverage were only available from 2016). Serotypes included in PCV13, PCV15, and PCV20 were identified for 14.1%, 14.5%, and 23.8% of all-cause CAP cases, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found in the percentage of all-cause CAP associated with PCV13-VT or PCV15-VT by age of the patients (Table 3). The percentage of all-cause CAP cases with identification of PCV20 serotypes was significantly higher in patients aged 18–64 years than in patients aged 65 years and older (27.7% vs 21.3%; P = .020).

Table 2.

Distribution of Vaccines Serotypes in All-Cause Community-Acquired Pneumonia and Pneumococcal Community-Acquired Pneumonia by Study Period

| Study Period | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–2012 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | Total | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| All-cause CAP | 431 | 14.3 | 434 | 14.4 | 393 | 13.0 | 339 | 11.2 | 489 | 16.2 | 507 | 16.8 | 514 | 17.0 | 3107 | 100 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 77 | 17.9 | 83 | 19.1 | 59 | 15.0 | 44 | 13.0 | 44 | 9.0 | 64 | 12.6 | 68 | 13.2 | 439 | 14.1 |

| PCV15 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 73 | 14.4 | 75 | 14.6 | 148 | 14.5 |

| PCV20 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 113 | 22.3 | 130 | 25.3 | 243 | 23.8 |

| Most prevalent serotypes (≥1% in total cases) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 13 | 3.0 | 12 | 2.8 | 6 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 36 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 25 | 5.8 | 32 | 7.4 | 23 | 5.9 | 22 | 6.5 | 28 | 5.7 | 40 | 7.9 | 45 | 8.8 | 215 | 6.9 |

| 7F | 11 | 2.6 | 8 | 1.8 | 9 | 2.3 | 4 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.4 | 39 | 1.3 |

| 8 | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 1.0 | 32 | 6.3 | 39 | 7.6 | 83 | 2.7 |

| 14 | 6 | 1.4 | 10 | 2.3 | 5 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.0 | 34 | 1.1 |

| 19A | 8 | 1.9 | 12 | 2.8 | 6 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.0 | 43 | 1.4 |

| CAP due to Streptococcus pneumoniae | 114 | … | 143 | … | 111 | … | 80 | … | 100 | … | 167 | … | 180 | … | 895 | 28.8 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 77 | 67.5 | 83 | 58.0 | 59 | 53.2 | 44 | 55.0 | 44 | 44.0 | 64 | 38.3 | 68 | 37.8 | 439 | 49.1 |

| PCV15 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 73 | 43.7 | 75 | 41.7 | 148 | 42.7 |

| PCV20 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 113 | 67.7 | 130 | 72.2 | 243 | 70.0 |

| Noninvasive CAPb | 95 | 83.3 | 112 | 78.3 | 96 | 86.5 | 71 | 88.8 | 81 | 95 | 136 | 81.4 | 155 | 86.1 | 746 | 83.4 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 64 | 67.4 | 60 | 53.6 | 50 | 52.1 | 43 | 60.6 | 38 | 46.9 | 54 | 39.7 | 64 | 41.3 | 373 | 50.0 |

| PCV15 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 61 | 44.9 | 70 | 45.2 | 131 | 45.0 |

| PCV20 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 90 | 66.2 | 112 | 72.3 | 202 | 69.4 |

| Invasive CAPc | 19 | 16.7 | 31 | 21.7 | 15 | 13.5 | 9 | 11.3 | 19 | 19.0 | 31 | 18.6 | 25 | 13.9 | 149 | 16.6 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 13 | 68.4 | 23 | 74.2 | 9 | 60.0 | 1 | 11.1 | 6 | 31.6 | 10 | 32.3 | 4 | 16.0 | 66 | 44.3 |

| PCV15 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 12 | 38.7 | 5 | 20.0 | 17 | 30.4 |

| PCV20 serotypesa | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | ND | … | 23 | 74.2 | 18 | 72.0 | 41 | 73.2 |

Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ND, not done; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; UAD, Pfizer serotype-specific urinary antigen detection test.

aPCV15 and PCV20 data were obtained only from 2016 to 2018 when the UAD2 test was available.

bConfirmed pneumococcal CAP (by UAD or BinaxNow) for which blood and/or pleural fluid culture result were negative.

cIsolate of S. pneumoniae in blood and/or pleural fluid. Among 149 cases identified, 6 isolates were not serotyped.

Table 3.

Distribution of Vaccine Serotypes by Age, 2016–2018

| 18–64 Years | ≥65 Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| All-cause CAP | 174 | 227 | 333 | 287 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 21 (12.1) | 29 (12.8) | 43 (12.9) | 39 (13.6) |

| PCV15 serotypes | 23 (13.2) | 30 (13.2) | 50 (15.0) | 45 (15.7) |

| PCV20 serotypes | 45 (25.9) | 66 (29.1) | 68 (20.4) | 64 (22.3) |

| Most prevalent serotypes (≥1% in total cases) | ||||

| 1 | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 3 | 15 (8.6) | 14 (6.2) | 25 (7.5) | 31 (10.8) |

| 7F | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| 14 | 2 (1.1) | 4 (1.8) | 4 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| 19A | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| 8 | 19 (10.9) | 27 (11.9) | 13 (3.9) | 12 (4.2) |

| CAP due to Streptococcus pneumoniae | 58 (33.3) | 83 (36.6) | 109 (32.7) | 97 (33.8) |

| PCV13 serotypes | 21 (36.2) | 29 (34.9) | 43 (39.4) | 39 (40.2) |

| PCV15 serotypes | 23 (39.7) | 30 (36.1) | 50 (45.9) | 45 (46.4) |

| PCV20 serotypes | 45 (77.6) | 66 (79.5) | 68 (62.4) | 64 (66.0) |

Among the invasive pneumococcal cases, 6 isolates were not serotyped.

Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Serotype 3 was the most frequently identified serotype accounting for 6.9% (n = 215) of all-cause CAP cases during the study period. In recent years (2016–2018) serotypes 3 and 8 were the most prevalent, with 8.3% and 7.0% respectively. Among invasive pneumococcal CAP cases, the most common serotypes identified were 8 (20.1%), 3 (14.2%), and 1 (11.4%) and in noninvasive cases were 3 (26%), 8 (7.1%), and 14 (3.9%).

The percentage due to PCV13 types was higher in the 3 sites located in regions with lower PCV13 pediatric uptake (see Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, Catalonia, Valencia, and Basque country had a PCV13 uptake ranging from 55% in Catalonia in 2012–2013 [23] and 78% in 2015, respectively [19], to 90.5% in Valencia (third dose) during 2015–2016 [24]. Among all-cause CAP cases, the percentage due to PCV13 serotypes was 10.5% in the site located in Pontevedra (Galicia) versus 17.7% (P = .057) in Barcelona (Catalonia), 12.3% (P = .209) in Valencia (Valencia), and 15.5% (P = .131) in Bizkaia (Basque Country) (Supplementary Table 2).

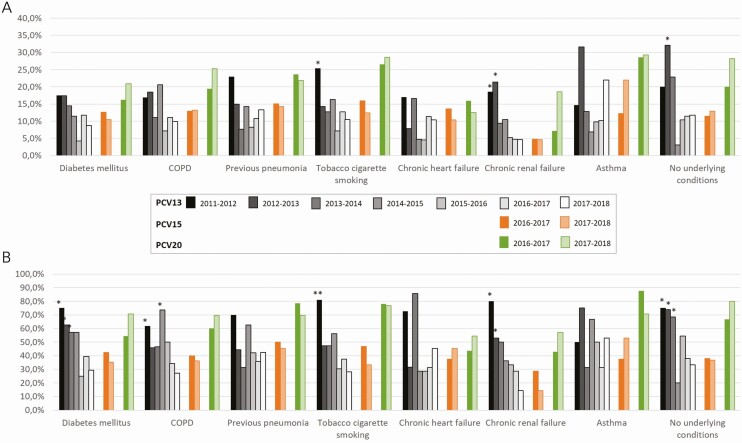

In 2016–2018, serotypes included in PCV13 accounted for 46.3%, 30.9%, and 37.4% of pneumococcal CAP in patients with 1, 2, and at least 3 underlying conditions, respectively (P = .146). PCV20 serotypes accounted for 75%, 66%, and 65.9% of pneumococcal isolates in patients with 1, 2, and at least 3 comorbidities, respectively (P = .352). PCV13 serotypes in pneumococcal CAP decreased significantly from 2011–2012 to 2017–2018 (P < .001) in all studied conditions except for chronic heart failure and asthma (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Serotype distribution (%) according to underlying conditions at admission and study period in all-cause (A) and pneumococcal (B) CAP. Note: Differences related to study period 2017–2018. *P < .05; **P < .001. Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Overall, the percentage of patients aged 18–64 years (n = 1164) with at least 1 underlying condition was 76.4%, and 93.5% in those aged 65 years and older (n = 1943). Table 4 shows serotype distribution by underlying conditions by age group for the study period 2016–2018. Among the patients aged 18–64 years, PCV13 serotypes accounted for 40% of pneumococcal CAP cases in adults with chronic heart failure and with diabetes mellitus. With regard to patients aged 65 years and older, the highest percentage of pneumococcal CAP caused by PCV13 serotypes was found in patients with asthma (53.3%). In this age group, the percentage due to PCV20 serotypes ranged from 45.5% to 75% in patients with chronic heart failure and cigarette smokers, respectively.

Table 4.

Serotype Distribution in All-Cause Community-Acquired Pneumonia and in Pneumococcal Community-Acquired Pneumonia According to Presence of Underlying Conditions by Age Group, 2016-2018

| Diabetes Mellitus | COPD | Previous Pneumonia | Tobacco Cigarrette Smokers | Chronic Heart Failure | Chronic Renal Failure | Asthma | No Underlying Diseases | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 18–64 y | ||||||||||||||||

| All-cause CAP (n = 401) | 46 | 11.5 | 39 | 9.7 | 66 | 16.4 | 141 | 35.2 | 13 | 3.2 | 6 | 1.5 | 48 | 12.0 | 95 | 23.7 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 6 | 13.0 | 5 | 12.8 | 7 | 10.6 | 14 | 9.9 | 2 | 15.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 12.5 | 11 | 11.6 |

| PCV15 serotypes | 7 | 15.2 | 6 | 15.4 | 7 | 10.6 | 15 | 10.6 | 2 | 15.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 14.6 | 12 | 12.6 |

| PCV20 serotypes | 12 | 26.1 | 11 | 28.2 | 13 | 19.7 | 37 | 26.2 | 3 | 23.1 | 2 | 33.3 | 15 | 31.3 | 25 | 26.3 |

| Most prevalent serotypes (≥1% in total cases) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 19A | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 3 | 6.5 | 3 | 7.7 | 6 | 9.1 | 7 | 5.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 8.3 | 7 | 7.4 |

| 7F | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.2 |

| 8 | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 7.7 | 5 | 7.6 | 20 | 14.2 | 1 | 7.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 7 | 14.6 | 11 | 11.6 |

| 12F | 1 | 2.2 | 2 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| CAP due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 141; 35.2%) | 15 | 10.6 | 18 | 12.8 | 19 | 13.5 | 47 | 33.3 | 5 | 3.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 18 | 12.8 | 31 | 22 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 6 | 40.0 | 5 | 27.8 | 7 | 36.8 | 14 | 29.8 | 2 | 40.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 33.3 | 11 | 35.5 |

| PCV15 serotypes | 7 | 46.7 | 6 | 33.3 | 7 | 36.8 | 15 | 31.9 | 2 | 40.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 38.9 | 12 | 38.7 |

| PCV20 serotypes | 12 | 80.0 | 11 | 61.1 | 13 | 68.4 | 37 | 78.7 | 3 | 60.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 15 | 83.3 | 25 | 80.6 |

| ≥65 y | ||||||||||||||||

| All-cause CAP (n = 620) | 180 | 29.0 | 160 | 25.8 | 132 | 21.3 | 58 | 9.3 | 79 | 12.7 | 79 | 12.7 | 42 | 6.8 | 60 | 9.7 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 17 | 9.4 | 16 | 10.0 | 17 | 12.9 | 9 | 15.5 | 8 | 10.1 | 4 | 5.1 | 8 | 19.0 | 7 | 11.7 |

| PCV15 serotypes | 19 | 10.6 | 20 | 12.5 | 22 | 16.7 | 13 | 22.4 | 9 | 11.4 | 4 | 5.1 | 8 | 19.0 | 7 | 11.7 |

| PCV20 serotypes | 30 | 16.7 | 33 | 20.6 | 32 | 24.2 | 18 | 31.0 | 10 | 12.7 | 9 | 11.4 | 11 | 26.2 | 13 | 21.7 |

| Most prevalent serotypes (≥1% in total cases) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0, | 0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 19A | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 14 | 7.8 | 10 | 6.3 | 14 | 10.6 | 5 | 8.6 | 5 | 6.3 | 1 | 1.3 | 6 | 14.3 | 6 | 10.0 |

| 7F | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 8 | 4.4 | 8 | 5.0 | 8 | 6.1 | 3 | 5.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 7.1 | 4 | 6.7 |

| CAP due to S. pneumoniae (n = 206; 33.2%) | 52 | 25.2 | 50 | 24.3 | 42 | 20.4 | 24 | 11.6 | 22 | 10.7 | 19 | 9.2 | 15 | 7.3 | 20 | 9.7 |

| PCV13 serotypes | 17 | 32.7 | 16 | 32.0 | 17 | 40.5 | 9 | 37.5 | 8 | 36.4 | 4 | 21.1 | 8 | 53.3 | 7 | 35.0 |

| PCV15 serotypes | 19 | 36.5 | 20 | 40.0 | 22 | 52.4 | 13 | 54.2 | 9 | 40.9 | 4 | 21.1 | 8 | 53.3 | 7 | 35.0 |

| PCV20 serotypes | 30 | 57.7 | 33 | 66.0 | 32 | 76.2 | 18 | 75.0 | 10 | 45.5 | 9 | 47.4 | 11 | 73.3 | 13 | 65.0 |

Patients might have >1 underlying condition. Six isolates of invasive pneumococcal pneumonias were not serotyped due to lack of sample or lysis.

Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

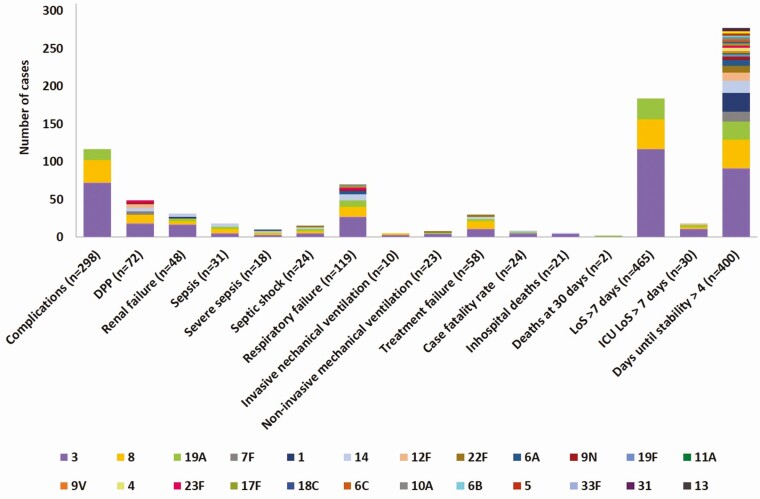

Pneumococcal Serotypes and Disease Severity

Serotypes associated with severity on admission were 3, 8, 19A, and 7F (Supplementary Table 3). Those serotypes were also predominant in patients with complicated CAP (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 4). Specifically, serotype 3 was found in 24.8% of pneumococcal CAP cases associated with complications occurring during hospitalization, with the highest representation of serotype 3 found in patients with renal failure (35.4% of patients with pneumococcal CAP and renal failure) or pleural effusion (25%) and those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (30.4%). A univariate analysis was used to evaluate the association between serotypes causing pneumococcal pneumonia and severity on admission or complications occurring during hospitalization (Table 5).

Figure 2.

Serotype distribution (number of cases) in pneumococcal CAP by complications during hospitalization (≥5% in total cases). Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; DPP, parapneumonic pleural effusion; ICU, intensive care unit; LoS, length of stay.

Table 5.

Serotypes Associated With Severity on Admission or Complications During Hospitalization

| Serotype | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CURB-65 risk classes 3–5 | |||

| 3 | .000 | 2.410 | 1.722–3.373 |

| Complicated pneumonia | |||

| 1 | .049 | 2.595 | 1.005–6.701 |

| 18C | .014 | .070 | .008–.581 |

| 3 | .018 | 1.496 | 1.071–2.091 |

| 7F | .014 | 3.663 | 1.297–10.343 |

| Sepsis/septic shock | |||

| 14 | .000 | 7.632 | 3.060–19.038 |

| 19A | .016 | 3.653 | 1.270–10.511 |

| 8 | .000 | 4.879 | 2.415–9.859 |

| 22F | .049 | 4.452 | 1.004–19.747 |

| ICU admission | |||

| 1 | .031 | 2.515 | 1.089–5.807 |

| 19A | .008 | 2.758 | 1.306–5.825 |

| 3 | .000 | 2.165 | 1.480–3.168 |

| 12F | .017 | 3.472 | 1.250–9.645 |

Only serotypes with significant values are shown in the table. For comparisons, no serotype identified is the reference parameter.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CURB 65, Score for Pneumonia Severity: Confusion, BUN > 19 mg/dL (> 7 mmol/L), Respiratory Rate ≥ 30, Systolic BP < 90 mmHg or Diastolic BP ≤ 60 mmHg, Age ≥ 65; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Our results showed that S. pneumoniae was the most frequent causative agent of hospitalized CAP identified in our population (28.8%), confirming the results of previous studies conducted in Spain [25, 26] and other countries [27, 28]. While the introduction of PCV13 into pediatric populations—in 2 regions with high coverage and in 1 region for a prolonged period—was associated with a decline in CAP associated with PCV13 serotypes, almost half of the pneumococcal CAP cases were caused by these serotypes, and this proportion increased over the last 3 study years, likely demonstrating a limit to herd immunity. This finding has been seen in other locations [20, 29] and may reflect for some serotypes—specifically, 3, 7F, 19A, and 19F—insufficient impact of PCV13 against carriage, short duration of protection against carriage, or transmission pathways other than from young children to adults. We also found evidence that the plateau in pediatric PCV13 indirect effects may be influenced by pediatric PCV13 coverage. Specifically, Galicia had the highest coverage and the lowest proportion of PCV13-VT in pneumococcal CAP while Catalonia showed the reverse. Nevertheless, in both regions, a plateau followed by an increase over the last study years was seen, consistent with data from the United Kingdom where similar findings were seen despite high pediatric PCV13 coverage [29].

Regardless of pediatric coverage and the specific mechanism involved, direct immunization of adults with high-valency PCVs may provide a solution. This approach is supported by robust vaccine efficacy against CAP due to serotypes 3, 7F, and 19A in a randomized controlled trial [22] and specifically for serotype 3 vaccine effectiveness in a “pooled analysis” [30]. While PCV13 could provide substantial benefit in preventing adult CAP, PCVs under development (PCV15 and PCV20), if licensed and efficacious, could provide marginally more value. For example, PCV20 serotypes were identified in 24% of CAP cases, compared to 14% for PCV13. The actual benefit of any particular PCV will depend on the specific serotypes, the contribution of these serotypes to CAP, the association of these serotypes with complicated or severe disease, and the serotype-specific vaccine effectiveness against CAP.

In our cohort, cases of complicated and severe CAP were common, and these were associated with specific serotypes. Serotype 3 was associated with both severe disease on admission and complications during hospitalization, consistent with results in children [31], in accordance with our results in adults. Serotype 8 is uncommonly carried in children but colonization in young adults has been observed before, and this population may represent the reservoir from which adult pneumococcal infections occur [32]. Both serotypes 3 and 8 remain commonly associated with adult CAP and their association with severe and complicated outcomes emphasizes the potential utility of existing and future vaccines.

Serotype 8 identification increased markedly over the last years of the study. Studies of hospitalized adults with CAP in the United Kingdom or in adults with IPD in Spain have reported similar results [29, 33]. In other countries, such as the United States, no increase in serotype 8 has been described [34]. Reasons for these disparities remain unknown but are consistent with an overall lower level of replacement disease in the United States versus Europe. Differences in serotype distribution at the time of pediatric PCV introduction may contribute. Additionally, the 2 regions have used pneumococcal vaccines in different ways. For example, Spain and the United Kingdom use a 2 + 1 pediatric PCV13 schedule, did not employ a pediatric catch-up strategy, and focus on PPSV23 for direct adult immunization [29, 33]; the United States uses PCV13 in a 3 + 1 infant schedule, employed a catch-up strategy to age 5 years, and uses both PCV13 and PPSV23 for direct adult immunization [34].

While our study design did not allow calculation of disease incidence, chronic conditions are recognized risk factors for CAP and pneumococcal disease [35]. Consistent with this, almost 90% of patients with CAP in our study had at least 1 comorbidity. Moreover, PCV13 serotypes were as common among persons with comorbidities as among persons without comorbidities. However, only 14.2% of the participants had received pneumococcal vaccination. These results reinforce the need for increasing awareness about the risk of CAP for patients with underlying conditions and about the pneumococcal serotype distribution in CAP according to the presence of comorbidities.

This study has some limitations. First, incidence rates could not be calculated and thus the possible impact of pediatric pneumococcal immunization on pneumococcal CAP in adults could not be properly assessed. Also, we report vaccination coverage of persons hospitalized with CAP, and this was substantially lower than national estimates from 2013–2014; however, we do not know the vaccination coverage specifically in most of the study regions, or among the persons most at risk of pneumonia. On the other hand, microbiological etiology could not be identified in 56% of the study participants. This is still a big challenge and, consequently, the majority of studies report a high percentage of undiagnosed pneumonia [36]. In addition, in our study, the UAD2 test was only available from 2016, limiting the analysis of the evolution in PCV20 serotypes to the last 2 study periods. Additionally, UAD1/2 assays are highly sensitive and specific for bacteremic pneumonia compared with the gold standard of blood culture. However, UAD1/2 sensitivity for nonbacteremic pneumonia is unknown because no reference standard exists [37]. Consequently, we may have underestimated the contribution of UAD1/2 serotypes to nonbacteremic pneumonia in our study. Moreover, while methodology and thus cutoffs for UAD1/2 positivity are similar across populations, some populations may have differences in cases that affect results—for example, antigenuria may, in theory, be lower in settings where patients present early or after pretreatment with antibiotics. On the other hand, our study did not enroll patients systematically, but this should not have affected results since characteristics of our study cohort are comparable to another Spanish study in which data on adults hospitalized with pneumococcal pneumonia were obtained from a national surveillance system for hospital data [38]. However, only hospitalized CAP cases were included in the study and results may not be representative of nonhospitalized patients with CAP. Finally, we included only immunocompetent patients and results may not apply to immunocompromised patients. A study of CAP cases in the United States found that approximately 46% of adults aged 65 years and older had an immunocompromising condition, emphasizing the importance of collecting information on this population [39].

Despite limitations, this large prospective cohort study describes trends in pneumococcal serotypes implicated in adult CAP over 8 years. Although the burden of PCV13 serotypes as a cause of pneumococcal CAP in immunocompetent adults in Spain is decreasing, it remains high. Given the current distribution of serotypes in Spain, direct vaccination with PCV13 currently and with extended spectrum vaccines in the future may help address CAP burden among adult populations, if combined with programs to improve coverage. Additionally, ongoing surveillance to monitor serotype evolution will be critical to optimizing immunization policy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the CAPA study group for their enthusiastic commitment to the study during all these years. The authors also thank Vanessa Marfil at Medical Statistics Consulting for medical writing services.

Financial support. This work was supported by Pfizer.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. T., R. Menéndez, P. P. E., J. A. F.-V., J. M. M., C. C., R. Méndez, M. E., M. B.-R., and M. E. received grants to their institutions from Pfizer S.L.U., Madrid, Spain, for this study. C. M. and I. C. are employees of Pfizer S.L.U., Madrid, Spain. B. D. G. is an employee of Pfizer Vaccines, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

CAPA Study Group. Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain): A. Torres, C. Cilloniz, A. Ceccato, A. San José, L. Bueno, F. Marco; Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (Valencia, Spain): R. Menéndez, R. Méndez, I. Amara, J. L. López Hontangas, B. Montull, A. Gimeno, A. Gil, A. Piro, P. González, E. Zaldivar, L. Feced, A. Latorre; Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo (Galdakao, Spain): P. P. España, M. Egurrola, A. Uranga, A. P. Martínez de la Fuente, A. Artaraz, N. Pérez; Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro (Vigo, Spain): A. Fernández-Villar, M. Botana-Rial, F. Vasallo, A. Priegue; Biodonostia, Hospital Universitario Donostia (San Sebastian, Spain): J. M. Marimón, E. Pérez-Trallero, M. Ercibengoa; Pfizer S.L.U (Madrid, Spain): C. Méndez, I. Cifuentes, C. Balseiro, M. Del Amo, A. García, J. Sáez, A. Perianes, A. Díaz, E. Garijo, E. Fernández, J. Martínez, R. Casassas, and M. L. Samaniego.

Contributor Information

CAPA Study Group:

A Torres, C Cilloniz, A Ceccato, A San José, L Bueno, F Marco, R Menéndez, R Méndez, I Amara, J L López Hontangas, B Montull, A Gimeno, A Gil, A Piro, P González, E Zaldivar, L Feced, A Latorre, P P España, M Egurrola, A Uranga, A P Martínez de la Fuente, A Artaraz, N Pérez, A Fernández-Villar, M Botana-Rial, F Vasallo, A Priegue, J M Marimón, E Pérez-Trallero, M Ercibengoa, C Méndez, I Cifuentes, C Balseiro, M Del Amo, A García, J Sáez, A Perianes, A Díaz, E Garijo, E Fernández, J Martínez, R Casassas, and M L Samaniego

References

- 1.G. B. D. Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1191–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres A, Blasi F, Dartois N, Akova M. Which individuals are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease. Thorax 2015; 70:984–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman C, Anderson R. The role of streptococcus pneumoniae in community-acquired pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 37:806–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network . Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Càmara J, Marimón JM, Cercenado E, et al. Decrease of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in adults after introduction of pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine in Spain. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0175224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picazo JJ, Ruiz-Contreras J, Casado-Flores J, et al. Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in children under 15years old in Madrid, Spain, 2007 to 2016: the HERACLES clinical surveillance study. Vaccine 2019; 37:2200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dirección Xeral de Innovación e Xestión da Saúde Pública-DXIXSP. Boletín Epidemiolóxico de Galicia. Volume XXVII, número 3. Xullo de 2015. Available at: https://www.sergas.es/Saude-publica/Boletin-epidemioloxico-Vol-XXVII-N3-Vacinación-infantil-VC13-Galicia-Catro-anos-estudo-piloto-Gripe-Galicia-tempada-201415. Accessed 17 June 2020.

- 8.Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Revisión del calendario de vacunación. Ponencia de Programa y Registro de Vacunaciones. Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/gl/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/docs/Revision_CalendarioVacunacion.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 9.Dirección General de Salud Pública Calidad e Innovación; Subdirección General de Promoción de la Salud y Vigilancia en Salud Pública; Secretaria General de Sanidad; Ministerio de Sanidad Coberturas de Vacunación. Datos estadísticos. Vacunación de recuerdo en población infantil. Evolución coberturas de vacunación de recuerdo. España 2008–2018 (actualización). Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/coberturas.htm. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 10.Comisión de Salud Pública del Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud; Ministerio de Sanidad Consumo y Bienestar Social; Grupo de Trabajo Vacunación en Población Adulta y Grupos de Riesgo. Vacunación en grupos de riesgo de todas las edades y en determinadas situaciones. Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/VacGruposRiesgo/Vac_GruposRiesgo_todasEdades.htm. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 11.Ministerio de Sanidad. Vacunación en población adulta2018. Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/docs/Vacunacion_poblacion_adulta.pdf. Accesed 26 June 2020.

- 12.Domínguez A, Soldevila N, Toledo D, et al. ; Project Pi12/02079 Working Group . Factors associated with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination of the elderly in Spain: a cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12:1891–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dirección General de Salud Pública; Consejería de Sanidad, Comunidad de Madrid. Calendario de vacunación del adulto 2019. Available at: http://www.madrid.org/bvirtual/BVCM020324.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2020.

- 14.Consejería de Sanidad Castilla y León; Junta de Castilla y León. Calendario vacunal para toda la vida. Available at: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/profesionales/es/vacunaciones/calendario-vacunal-toda-vida. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 15.Gobierno de La Rioja, Consejería de Salud. Calendario Oficial de Vacunaciones Sistemáticas de la Comunidad Autónoma de La Rioja. Available at: http://www.riojasalud.es/f/rs/docs/2017_orden2_2017_de_22_de_marzo.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 16.Consejería de Sanidad; Dirección General de Salud Pública; Gobierno del Principado de Asturias. Actualizaciones en el Programa de Vacunaciones de Asturias para 2017. Available at: https://www.astursalud.es/documents/31867/430382/5_Circular+DGSP+2017_02_Actualizacion+programa+de+vacunaciones+2017.pdf/5f2aca67-567d-fcec-6781-431452fd1b03. Accessed 17 June 2020.

- 17.Xunta de Galicia. Calendario de vacunación adulto. Available at: https://www.sergas.es/Saudepublica/Documents/4504/calend_vacunacion_adultos_castellano.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 18.Junta de Andalucía; Consejería de Salud y Familias. Programa de vacunación frente al neumococo. Instrucción DGSPyOF-3/2019. Available at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/Instruccion_Neumococo_Andalucia_Julio2019.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 19.Hanquet G, Krizova P, Valentiner-Branth P, et al. ; SpIDnet/I-MOVE+ Pneumo Group . Effect of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive disease in older adults of 10 European countries: implications for adult vaccination. Thorax 2019; 74:473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Linden M, Imöhl M, Perniciaro S. Limited indirect effects of an infant pneumococcal vaccination program in an aging population. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0220453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menéndez R, España PP, Pérez-Trallero E, et al. The burden of PCV13 serotypes in hospitalized pneumococcal pneumonia in Spain using a novel urinary antigen detection test: CAPA study. Vaccine 2017; 35:5264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gessner BD, Jiang Q, Van Werkhoven CH, et al. A post-hoc analysis of serotype-specific vaccine efficacy of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against clinical community acquired pneumonia from a randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2019; 37:4147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domínguez Á, Ciruela P, Hernández S, et al. Effectiveness of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in preventing invasive pneumococcal disease in children aged 7-59 months: a matched case-control study. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0183191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastor-Villalba EJAL-RJ, Sanchis-Ferrer A, Alguacil-Ramos AM, Portero-Alonso A. Vaccination with pneumococcal conjugate 13-valent vaccine in children younger than 15 years. Valencia region (Spain). Year 2016. Abstract ESP17-0420 presented at: 35th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID); 23–27 May 2017; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polverino E, Torres A, Menendez R, et al. ; HCAP Study Investigators . Microbial aetiology of healthcare associated pneumonia in Spain: a prospective, multicentre, case-control study. Thorax 2013; 68:1007–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallés J, Martin-Loeches I, Torres A, et al. Epidemiology, antibiotic therapy and clinical outcomes of healthcare-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients: a Spanish cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40:572–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim WS, Macfarlane JT. A prospective comparison of nursing home acquired pneumonia with community acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2001; 18:362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shindo Y, Sato S, Maruyama E, et al. Health-care-associated pneumonia among hospitalized patients in a Japanese community hospital. Chest 2009; 135:633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pick H, Daniel P, Rodrigo C, et al. Pneumococcal serotype trends, surveillance and risk factors in UK adult pneumonia, 2013-18. Thorax 2020; 75:38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin JM, Jiang Q, Gessner BD, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against serotype 3 pneumococcal pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Vaccine 2019; 37:6310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madhi F, Levy C, Morin L, et al. ; Pneumonia Study Group; GPIP (Pediatric Infectious Disease Group) . Change in bacterial causes of community-acquired parapneumonic effusion and pleural empyema in children 6 years after 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine implementation. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019; 8:474–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adler H, Nikolaou E, Gould K, et al. Pneumococcal colonization in healthy adult research participants in the conjugate vaccine Era, United Kingdom, 2010–2017. J Infect Dis 2019; 219:1989–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Miguel S, Domenech M, Gonzalez-Camacho F, et al. Nationwide trends of invasive pneumococcal disease in Spain (2009–2019) in children and adults during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Clin Infect Dis 2020; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suaya JA, Mendes RE, Sings HL, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype distribution and antimicrobial nonsusceptibility trends among adults with pneumonia in the United States, 2009‒2017. J Infect 2020; 81:557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres A, Lee N, Cilloniz C, Vila J, Van der Eerden M. Laboratory diagnosis of pneumonia in the molecular age. Eur Respir J 2016; 48:1764–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalina WV, Souza V, Wu K, et al. Qualification and clinical validation of an immunodiagnostic assay for detecting 11 additional streptococcus pneumoniae serotype-specific polysaccharides in human urine. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:e430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gil-Prieto R, Pascual-Garcia R, Walter S, Álvaro-Meca A, Gil-De-Miguel Á. Risk of hospitalization due to pneumococcal disease in adults in Spain: the CORIENNE study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12:1900–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaughlin JM, Jiang Q, Isturiz RE, et al. Effectiveness of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in older US adults: a test-negative design. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 1498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.