Abstract

The American Lymphedema Framework Project (AFLP) surveyed lymphoedema therapists in the US in 2009 to describe their preparation, patient population and care practices. In the autumn of 2018, the survey was expanded to trained therapists worldwide to describe and compare current and past therapist characteristics and practices. The updated 2009 survey was distributed via Qualtrics to US and international therapists. The current analysis includes over 950 completed surveys. Preliminary results showed: country: US (n=672/922 [73%]); Canada (n=92[10%]); United Kingdom (n=42[5%]); Australia (n=28[3%]); gender: identifying as female (n=633/676 [93%]); mean age: 47yrs (range 21–76); discipline: physical therapist [45%], occupational therapist [31%], massage therapist [24%]); mean practice years: 10.7yrs (range 0–41); and practice setting: hospital out-patient clinic (47%); private practice (38%); hospital in-patient (13%); home care/hospice (9%). Further 2009–2018 comparative analyses will be shared. Understanding characteristics and practices of lymphoedema therapists and patients will help stakeholders meet under- and unmet needs of this population.

Keywords: Lymphoedema therapists, survey

Over 200 million people around the world have or are at risk of developing lymphoedema (Grada and Phillips, 2017). Lymphoedema is a failure of the lymphatic transport system, resulting from cancer treatment, infection, trauma, and/or genetic/ familial structural malformations leading to distressing and debilitating swelling of the affected area (International Society of Lymphology [ISL], 2016; Armer et al, 2018). Volume reduction and symptom management by a trained lymphoedema therapist is critical to improving symptoms and maintaining quality of life (ISL, 2016). Certification training involves licensed healthcare professionals completing a 135-hour didactic course and 1 year of clinical practice in lymphoedema management (Lymphology Association of North America [LANA], 2017; North American Lymphoedema Education Association [NALEA], 2017). LANA certification is voluntary and available worldwide. The goal of this updated survey by the American Lymphoedema Framework Project (ALFP) was to determine the current state of lymphoedema care and practice characteristics worldwide as reported by the therapists.

The ALFP is a national, United States-based collaboration of healthcare providers, researchers, patients, advocates, educators, industry representatives and third-party payers led by recognised clinical experts and investigators in lymphoedema care (ALFP, 2019). Since 2008, its mission has been to evaluate appropriate healthcare services for patients with all forms of lymphoedema and advance the quality of lymphoedema care both in the US and worldwide. The partnership with the International Lymphoedema Framework (ILF) has resulted in increased global awareness and research advancement towards improving functional, physical, and quality of life outcomes for patients with lymphoedema (Armer et al, 2010; International Lymphedema Framework, 2019).

Between 2008 and 2014, five ‘open-space’ stakeholder meetings were held to ensure focus on priority issues remained current: Chicago, IL; Columbus. OH; Atlanta, GA; Columbia, MO; and Cape Town, South Africa (Armer et al, 2017). The international meeting held in Cape Town contributed to the eventual formation of the Lymphoedema Association of South Africa (LAOSA) (Lymphedema Association of South Africa, 2019). The 2008 issues were confirmed at each meeting and continue to be priorities, with awareness and education ranked first:

Increase awareness of lymphoedema and related lymphatic system disorders

Improve patient education, support, and self-management

Establish criteria for health provider education

Continue to build the credibility of the ALFP

Develop and implement research to refine diagnostic standards and provide evidence for effective treatments

Promote evidence-based practice for lymphoedema management

Improve reimbursement for lymphoedema care and resources.

ALFP goals of building a minimum dataset (MDS) to support outcomes research and defining best practice for lymphoedema care have matured since 2008. The MDS contains over 1,300 patients with data points including volume measurements, symptoms, and longitudinal visit information (Armer et al, 2017). Data-mining tools and a 3-D mobile imaging platform allow more research questions to be explored and increase accuracy and frequency of lymphoedema measurements. Best practice aims fostered the completion of 11 systematic reviews addressing lymphoedema care outcomes, providing healthcare professionals with information to support clinical practice. In addition, the ALFP Therapist Directory ‘Look4LE’ continues to expand, registering information on over 1,200 LANA-certified US and international therapists (Armer et al, 2017).

The priority of increasing lymphedema awareness and education motivated the ALFP national survey of lymphoedema therapists in 2009, with a follow-up survey encouraged by NALEA training schools in 2011. Continued growth of the therapist directory, new lymphoedema management research results, and the continued recognition of gaps in provider education that affect the care of patients with lymphoedema (Ng et al, 2015; Armer et al, 2017) was a catalyst for the authors to explore current practice environments and educational frameworks of therapists in both the US and worldwide.

Methods

Between June and July 2018, the 2009 ALFP survey was updated. Online searches reviewed treatment types, referral sources, measurement methods, payment methods, patient educational resources, licensure processes, and sources of licensure training to determine changes since 2009. The survey questions were reviewed by research team members and edited through electronic review. The final survey included 56 items that were imported into Qualtrics™(Qualtrics, Provo: UT). The items queried information about therapists’ demographics, practice location, patient population, therapy modalities, training processes, treatment payment sources and practice setting descriptions. This study was approved as an exempt study by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board.

Lymphoedema therapists were invited to complete the survey by email invitation sent from the ALFP stakeholder database. Snowball-sampling techniques were used, such as inviting recipients to forward the survey link to eligible colleagues. Additional network members and partnership organisations were invited to forward the survey link to contacts and therapists on their membership lists. The survey was available for online completion for 8 weeks from October through December 2018.

Results

Demographics

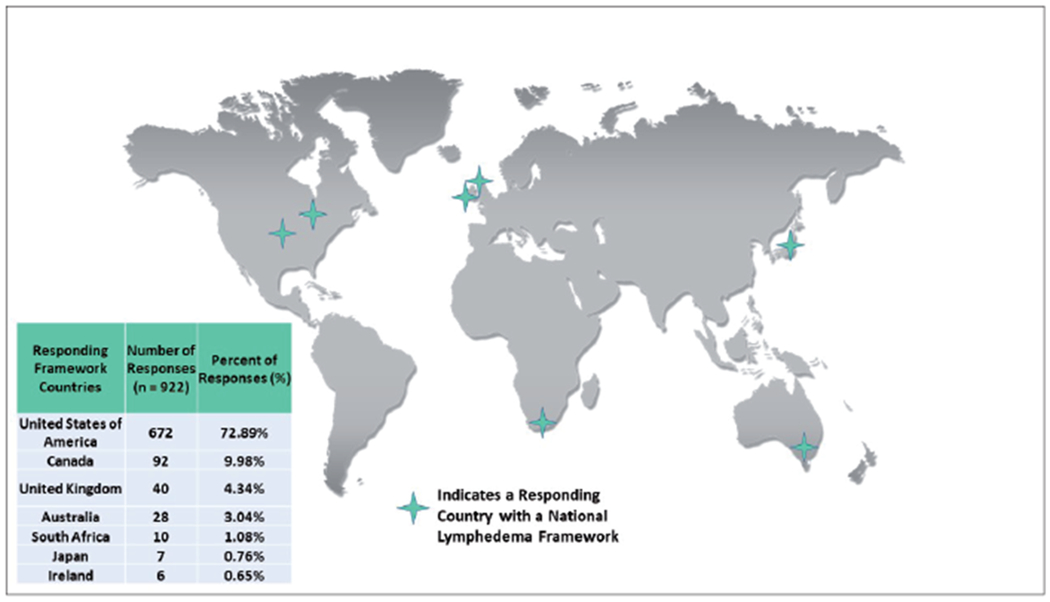

Data were submitted by 950 therapists from all 50 states of the United States (US) (n=662) and all seven Canadian provinces, along with 41 additional countries (n=288) (Figure 1). The majority of respondents self-identified as female (93%), with an average age of 47 years (range 21–76) (Table 1). The three most frequent disciplines reported were physical therapy (45%); occupational therapy (31%); and massage therapy (24%). Mean reported years in practice was 10.7 years (range 0–41). The majority of therapists (96%) self-reported they met the 135-hour training requirement to be recognised as a Certified Lymphedema Therapist (CLT) and 33% reported achieving LANA certification. The top four reported practice settings included: hospital outpatient clinic (47%); private practice (38%); hospital inpatient (13%); and home care/hospice (9%). A descriptive summary of the data is provided, with number of responses varying from 680–719 for each question because participants were not required to answer all questions.

Figure 1.

Framework countries responding to the therapist survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of lymphoedema therapists.

| Gender identification | Age | Years of treating lymphoedema |

|---|---|---|

| Female = 94% | Mean = 47.4 years (SD ± 11 years) Minimum = 21 years |

Mean = 10.7 years (SD ± 7.7 years) Minimum = 1 month |

|

| ||

| Male = 6% | Maximum = 76 years | Maximum = 41 years |

Treatment

The most commonly-reported treatments offered by responding lymphoedema therapists were the various elements of comprehensive decongestive therapy (CDT), consisting of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), compression bandaging and compression garments, exercise, movement, risk-reduction education, skin care and soft tissue mobilisation. Less than 15% of responding therapists reported offering single-phase pneumatic compression devices, aquatic treatment, low-level laser, vibrator treatment, compression bandage only, reflexology and other treatments. A majority (55%) of therapists offered seven or more treatment options.

On average, therapists reported that 80% of patients treated had secondary lymphoedema. Lymphoedema therapists also reported treating patients with the following areas of oncology-related lymphoedema: upper extremities (53%); lower extremities (30%); trunk (7%); head and neck (8%); and genitals (2%). Concerning the comparison between wound care and lymphoedema management, therapists, on average, reported that 81% of their patients required lymphoedema care only; 3% required wound care only; and 16% required both.

Further descriptive-comparative analyses will be performed to compare 2009 and 2018 findings. Overall, preliminary findings from the updated survey reveal modest variance from the 2009 survey, on average 0–4%. A companion manuscript detailing the comparative analysis is forthcoming.

Discussion

All 50 US states, all seven Canadian provinces, and an additional 41 countries had representation in this 2018 ALFP-sponsored lymphoedema therapist survey. The high level of training among therapists could be due to selection bias related to the method of survey dissemination and differential access to the online survey. It could also be that highly-prepared therapists are more likely to respond. One-third of the therapists reported they held LANA certification. We note that all findings are self-reported and not verified with national certification or training databases due to anonymity of responses.

The largest percentage of therapists were licensed as physical therapists, occupational therapists and massage therapists. A smaller percentage were licensed as advance practice nurses, athletic trainers and exercise physiologists. The majority of responding therapists practiced in hospital-based out-patient clinics and private practices, with a lesser percentage practicing in hospital-based inpatient services, and home care/hospice. Less than 10% reported working in any one of the following: comprehensive cancer centres; singlesite clinics; multi-site clinics; community cancer centres; and other sites. Treatment with CDT was available in almost all clinical settings, while other options, such as exercise and risk-reduction education were also provided. Therapists reported that 80% of their patients had secondary lymphoedema, of whom 53% had oncology-related, upper-extremity lymphoedema. Even with the expansion of the survey to the international arena and a greater than 40% increase in sample size, the responses appear to be quite stable overall in this 9-year period.

Conclusion

With this update to the 2009 survey, we were able to continue exploring the perspectives and practices of therapists from around the world for over a decade. Lymphoedema therapists are critical members of the health care team providing care to persons with and at risk of lymphoedema from all causes. Understanding the training, characteristics, and practices of lymphoedema therapists and their patients will help health professionals, educators, policymakers, and funders better meet the under- and unmet needs of this growing population.

Acknowledgements

Findings were reported in part in a poster presentation at the 43rd Annual Midwest Nursing Research Society research conference in Kansas City, March 2019. Findings were accepted for an oral presentation at the ninth International Lymphoedema Framework Conference, co-hosted by the American Lymphoedema Framework, in Chicago, IL, June 2019. The authors gratefully acknowledge Wesley JL Anderson for his contribution to analysis and discussion. First author Elizabeth A Anderson is funded as a pre-doctoral fellow by the National Institutes of Health T32 Health Behavior Science Research Training Grant 5T32NR015426 at the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A Anderson, Health Behavior Science T32 Doctoral Fellow, Sinclair School of Nursing, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA.

Allison B Anbari, Assistant Research Professor, Sinclair School of Nursing, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA.

Nathan C Armer, Research Assistant, Sinclair School of Nursing, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA.

Jane M Armer, Professor, University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, Director, T32 Health Behavior Science Training, Director, Nursing Research, Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Director, American Lymphoedema Framework Project.

References

- American Lymphedema Framework Project (2019) American Lymphedema Framework Project. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Ih3M4m (accessed 04.06.2019) [Google Scholar]

- Armer JM, Paskett ED, Fu MR et al. (2010) A survey of lymphoedema practitioners across the US. Journal of Lymphoedema 5(2): 95–7 [Google Scholar]

- Armer JM, Armer NC, Feldman JL (2017) American Lymphoedema Framework Project: An Overview of 8 years in Moving the Lymphoedema Field Forward. Paper presentation at the 28th International Nursing Research Congress, Dublin, Ireland, July 2017. Available at: https://bit.ly/310C1FA (accessed 04.06.2019) [Google Scholar]

- Armer JM, Ballman KV, McCall L et al. (2018) Lymphoedema symptoms and limb measurement changes in breast cancer survivors treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and axillary dissection: results of American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z1071 (Alliance) substudy. Support Care Cancer 27(2): 495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EA, Anbari AB, Armer NC, Armer JM (2019) Understanding the practices of trained lymphoedema therapists, then and now. Poster presentation at Midwest Nursing Research Society, Kansas City, MO, March 29, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E, Anbari A, Armer N, Armer J (2019) American Lymphoedema Framework Project (ALFP) Survey of Lymphoedema Therapists: A 2018 Update. Paper presented at the 9th International Lymphoedema Framework Conference, Chicago, IL, June 13–15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lymphology Association of North America (2019). LANA Mission Statement. Available at: https://bit.ly/2WcGaCX (accessed 04.06.2019)

- Lymphology Association of North America (2019) LANA Candidate Information Booklet. Available at: https://bit.ly/2KVcZC2 (accessed 04.06.2019)

- Grada AA, Phillips TJ (2017) Lymphoedema: pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol 77(6): 1009–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Lymphoedema Framework (2019). About Us. Available at https://bit.ly/2WHzyRb (accessed 04.06.2019)

- International Society of Lymphology (2016) The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphoedema: 2016 consensus document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 49(4): 170–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoedema Association of South Africa (2019). About Us. Available at: https://bit.ly/2Z768t7 (accessed 04.06.2019)

- North American Lymphedema Education Association (2019) Positions. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HU6768 (accessed 04.06.2019)

- National Lymphedema Network Medical Advisory Committee (2011) The Diagnosis and Treatment of Lymphedema: Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. Available at: https://bit.ly/2HtLPk1 (accessed 04.06.2019)

- Ng T, Toh MR, Cheung YT, Chan A (2015) Follow-up care practices and barriers to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives from Asian oncology practitioners. Support Care Cancer 23(11): 3193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]