Abstract

Accumulating evidence implicates the transcription factor NF-κB as a positive mediator of cell growth, but the molecular mechanism(s) involved in this process remains largely unknown. Here we use both a skeletal muscle differentiation model and normal diploid fibroblasts to gain insight into how NF-κB regulates cell growth and differentiation. Results obtained with the C2C12 myoblast cell line demonstrate that NF-κB functions as an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. Myoblasts generated to lack NF-κB activity displayed defects in cellular proliferation and cell cycle exit upon differentiation. An analysis of cell cycle markers revealed that NF-κB activates cyclin D1 expression, and the results showed that this regulatory pathway is one mechanism by which NF-κB inhibits myogenesis. NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 occurs at the transcriptional level and is mediated by direct binding of NF-κB to multiple sites in the cyclin D1 promoter. Using diploid fibroblasts, we demonstrate that NF-κB is required to induce cyclin D1 expression and pRb hyperphosphorylation and promote G1-to-S progression. Consistent with results obtained with the C2C12 differentiation model, we show that NF-κB also promotes cell growth in embryonic fibroblasts, correlating with its regulation of cyclin D1. These data therefore identify cyclin D1 as an important transcriptional target of NF-κB and reveal a mechanism to explain how NF-κB is involved in the early phases of the cell cycle to regulate cell growth and differentiation.

NF-κB belongs to the Rel family of transcription factors which regulate genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses (3, 5, 70). In mammals, the Rel family is composed of RelA/p65, c-Rel, RelB, p50 (NF-κB1), and p52 (NF-κB2), which have sequence similarity over approximately 300 amino acids in the amino-terminal half of the protein. NF-κB subunits are able to homo- or heterodimerize to form transcription factor complexes with a range of DNA-binding and activation potentials. Although all Rel members bind DNA, only RelA/p65 (hereafter referred to as p65), c-Rel, and RelB have extended carboxy termini harboring transactivation function (70). The most widely studied form of NF-κB is a heterodimer of the p50 and p65 subunits and is a potent activator of gene transcription (56).

In most cells, NF-κB is found sequestered in the cytoplasm bound in an inactive complex with its natural biological inhibitor IκB (3, 70). The IκB family members include IκBα, IκBβ, p105/IκBγ (precursor of p50), p100 (precursor of p52), and IκBɛ (41, 74). Each has in common a series of ankyrin repeats which interact with the DNA-binding domain and the nuclear localization signal of NF-κB, thus maintaining the transcription factor as an inactive complex. Activation of NF-κB is induced by a variety of diverse stimuli including inflammatory cytokines, phorbol esters, bacterial toxins (such as lipopolysaccharide) viruses, UV light, and a variety of mitogens (4, 5). Treatment of cells with these stimuli activate the recently discovered IκB kinase complex, leading to the phosphorylation of serines 32 and 36 of IκBα or serines 19 and 23 of IκBβ (19, 46, 52, 77). This phosphorylation event targets IκB for ubiquitin-dependent degradation through the 26S proteasome complex, resulting in the release and nuclear translocation of NF-κB (22, 68).

In addition to its well-established role in activating the transcription of genes involved in immunological responses, studies indicate that NF-κB also functions in promoting cell growth. For instance, lymphocytes from mice lacking p50, p65, or c-Rel are defective in mitogenic responses (20, 38, 58, 65), and p50/p52 double-knockout animals fail to generate mature osteoclasts and B cells (25, 35). Recent reports also demonstrate the expression of NF-κB/Rel proteins in the proliferative zone of the developing avian limb bud and the requirement of NF-κB for the proper growth of this tissue (15, 36). In addition, deregulated NF-κB activity has been associated with oncogenesis, since reports show elevated NF-κB/Rel levels in primary breast cancers (18, 66). NF-κB is activated by oncogenic Ras and is required by Ras to induce foci in NIH 3T3 cells (23). Similarly, the chimeric oncoprotein Bcr-Abl, implicated in acute lymphoblastic and chronic myelogenous leukemias, also requires NF-κB to induce cellular transformation (54). Consistent with this latter study, Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells depleted of NF-κB activity revealed strongly impaired tumor growth in mice (7). The ability of NF-κB to protect cells against chemotherapeutic drugs or TNF-mediated apoptosis function (9, 69, 72, 75), suggests that NF-κB-regulated growth control may be related to its cell survival properties. In fact, inhibition of NF-κB led to apoptosis in cells expressing oncogenic forms of Ras (45). Finally, recent demonstrations that cellular proliferation defects, attributed to the absence of NF-κB, are associated with a delay in cell cycle progression in G1 (7, 28), in addition to the previously described physical association with NF-κB and CBP/p300 (26, 50), establishes a link between NF-κB and regulators of the cell cycle. Although the above cited reports strongly suggest a role for NF-κB in cell growth control, the molecular mechanism(s) underlying this regulation remains unclear.

To gain insight into the role of NF-κB in regulating cell growth, we first used a well-established skeletal myogenesis model, which is characterized by the maturation of precursor myoblasts into differentiated contractile myotubes. This cellular process is dependent on the activation or induction of the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) and MEF2 families of transcription factors that stimulate tissue-specific gene expression, as well as changes in cell cycle regulators that cause myoblasts to undergo irreversible growth arrest (39, 48, 71). The latter process is regulated by a balance in activities of cyclin–cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) complexes and their respective known kinase inhibitors. The signal to induce differentiation, achieved most commonly in tissue culture by removing growth factor-rich medium, causes the downregulated expression of cyclins A and D1 and kinases cdk2 and cdc2, with an induced synthesis of the cdk inhibitors p18 and p21 and stabilization of the p27 protein (71). This regulated switch in activities leads to the dephosphorylation of the product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene (pRb), which maintains cells in a G1-arrested state by inhibiting the E2F-DP1 transcription factor complex. Exit from the cell cycle, therefore, is critical for myogenic transcription and completion of the differentiation program.

Using the murine C2C12 skeletal muscle cell line, we demonstrate that NF-κB functions in proliferating myoblasts to inhibit their differentiation process. This was determined by showing that C2C12 myoblasts contain NF-κB in their nuclei and that NF-κB DNA-binding activity and transactivation function are reduced during myogenesis. In addition, myoblasts generated to lack NF-κB activity are greatly accelerated in their differentiation program. Transfections in 10T1/2 cells showed that NF-κB strongly blocks the ability of the myogenic transcription factor, MyoD, to induce myogenesis. Furthermore, this latter regulation is specific to the transactivation-competent p65 subunit of NF-κB, arguing that NF-κB inhibits myogenic differentiation through its activation of gene expression. The observation that C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB display a reduction in their proliferation rate and exit the cell cycle faster than do control cells suggests that inhibition of myogenesis by NF-κB is in part related to its growth-promoting activity. Importantly, these cells also exhibit a marked reduction in cyclin D1 protein and mRNA levels. The results of experiments performed with 10T1/2 fibroblasts indicate that NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 is one mechanism by which this transcription factor inhibits myogenic differentiation. From this differentiation model, we expanded our study to identify the level at which NF-κB regulated cyclin D1. The results show that this regulation occurs at the transcriptional level and is mediated by several authentic NF-κB DNA-binding sites in the cyclin D1 promoter. Furthermore, by using diploid fibroblasts, we addressed the potential relevance of NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 with respect to the cell cycle. Our data show that in cells stimulated to reenter the cell cycle, NF-κB activity is required for cyclin D1 transcriptional initiation and hyperphosphorylation of pRb, leading to progression into S phase. Similar to what was observed in C2C12 cells, embryonic fibroblasts lacking NF-κB activity also exhibit a reduction in proliferation, in conjunction with lower levels of cyclin D1. Taken together, these data establish that the ability of NF-κB to control cellular proliferation and differentiation are processes tightly coupled to its ability to transcriptionally regulate cyclin D1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Murine C2C12 myoblast cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and primary murine myoblasts (a generous gift from J. Samulski) were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with high glucose (DMEM-H), supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (Life Technologies). The cells were grown at subconfluency and passaged every 2 to 3 days. To induce differentiation, the cells were grown overnight to 60 to 70% confluency in growth medium (GM), washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then switched to DMEM-H supplemented with 2% horse serum and 10 μg of insulin per ml plus antibiotics (DM). C3H10T1/2 clone 8 mouse embryo fibroblasts (10T1/2), also obtained from American Type Culture Collection, were cultured in DMEM-H containing 15% FBS plus antibiotics and passaged every 2 to 3 days. HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM-H with 5% FBS and 5% calf serum, NIH 3T3 cells were grown in DMEM-H with 10% Colorado calf serum, and for mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), cells were grown in DMEM-H plus 10% FBS.

Plasmids.

For reporter plasmids, 3xκB-Luc or 3xκBmut-Luc contain three tandem repeats of the wild-type or mutated κB site, from the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I enhancer, respectively, fused to the luciferase reporter gene (obtained from B. Sugden, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis.). TnI-Luc contains a muscle-specific enhancer in the troponin I gene fused to luciferase, and 4RTK-Luc contains four E boxes from the muscle creatine kinase enhancer (gifts of S. Konieczny, Purdue University). Cyclin D1 promoter reporter constructs were described earlier (1). For expression plasmids, p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB were expressed from a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven promoter as previously described (10). The mutant IκBα plasmid, designated IκBαSR, was a gift of D. Ballard (Vanderbilt University). A cyclin D1 expression plasmid was generated by removing a 1,300-bp EcoRI fragment containing the mouse cyclin D1 cDNA from the pBSSK plasmid and inserting it into the EcoRI site of pCMV5. pCDNA3-D3 plasmid expressing human cyclin D3 was a gift of C. Sherr (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital). pEMC11s plasmid expressing MyoD was obtained from the H. Weintraub laboratory (University of Washington). Oncogenic ras was expressed from the H-ras (V-12) plasmid as previously described (45).

EMSAs.

Nuclear extracts for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were prepared as previously described (16), except that 0.25% Nonidet P-40 was used to extract nuclei. A 5-μg portion of extract were preincubated with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) in a volume of 12 μl for 10 min. This mixture was subsequently incubated in a total volume of 20 μl at room temperature for 20 min with 2 × 104 cpm of a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe containing a κB site (underlined) from the class I MHC promoter (5′-CAG GGC TGG GGA TTC CCC ATC TCC ACA GTT TCA CTT C-3′). The buffer consisted of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 10% glycerol. Complexes were resolved on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-glycine buffer (25 mM Tris, 190 mM glycine, 1 mM EDTA) at 25 mA for 2 to 3 h at room temperature. The gels were dried and exposed on film for approximately 1 to 3 days. For supershift EMSAs, antibodies against specific NF-κB were added to the nuclear extract and incubated for 10 min prior to the addition of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC). The antibodies used for this portion of the study were p65 (Rockland), p50 (NLS; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), c-Rel (C; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and RelB (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). NF-κB-binding sites in the cyclin D1 promoter were determined by generating a series of oligonucleotides corresponding to both wild-type and mutant (M) putative NF-κB sites within the human cyclin D1 promoter (47). The oligonucleotides have the following sequences (NF-κB wild-type and mutated sites are underlined): −858, 5′-GTG CAG TTG GGG ACC CCC GCA AGG ACC GAC TGG TCA A-3′; −858(M), 5′-GTG CAG TTC CCG ACC CCC GCA AGG ACC GAC TGG TCA A-3′; −749, 5′-ACC ATC TTG GGC TGC TGC TGG AAT TTT CGG GCA TTT A-3′; −749(M), 5′-ACC ATC TTG GGC TGC TGC TCC CCT TTT CGG GCA TTT A-3′; −39, 5′-GGA CTA CAG GGG AGT TTT GTT GAA GTT GCA AAG TCC T-3′; and −39(M), 5′-GGA CTA CAC CCC AGT TTT GTT GAA GTT GCA AAG TCC T-3′.

Transfections and viral infections.

To generate C2C12 cells with stably integrated luciferase reporter plasmids, cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells in 6-cm dishes 24 h prior to transfection. Cotransfections with 4 μg of reporter plasmid 3xκB-Luc or 3xκBmut-Luc and 1 μg of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) containing the neomycin resistance marker were performed with Superfect reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were trypsinized and cultured at 1/30 their density in 1 mg of Geneticin (G418; Life Technologies) per ml. Mixed populations containing either wild-type or mutant versions of the κB sites were allowed to expand under selection, and from the wild-type population an individual clone expressing similar basal promoter activity was selected. Cell extracts were prepared and luciferase assays were performed as previously described (16).

C2C12 cells stably expressing IκBαSR or empty vector were generated by retroviral infections as previously described (54). The cells were seeded under identical conditions to those stated above. Helper-free virus infection was performed in 1 ml of culture in the presence of 2 μg of Polybrene for 3 h. Culture medium was aspirated, and fresh medium was added for 48 h. The cells were then trypsinized and replated in G418-containing medium at 1 mg/ml at a ratio of 0.7 cell/well in a 96-well plate. The selection medium was replaced every 4 to 5 days, and individual clones were expanded for further study. To produce MEFs stably expressing IκBαSR, retrovirus infections were performed as described above. The cells were then placed under a 3-day selection of G418 at 400 μg/ml and subsequently expanded as a mixed population for further study.

Transient transfections into 10T1/2 fibroblasts were performed by seeding 5 × 105 cells in a 6-cm dish and growing the cells overnight in complete medium. The following day, a total of 2.5 μg of plasmid DNA was incubated with Superfect as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). This mixture was subsequently added to the cells with 1 ml of complete medium for approximately 3 h. The cells were rinsed with PBS and then refed with 4 ml of complete medium overnight. At this point, the cells were again rinsed once with PBS and then transferred to DM for a 48-h period. Cell extracts were prepared and luciferase activity was monitored as previously described (16).

For adenovirus infections in cycling cells, HeLa cells and MEFs were plated overnight in 10-cm culture dishes. The following day, replication-defective adenovirus (Ad5) expressing the IκBαSR or empty vector (CMV) were diluted in 2.5 ml of complete medium and placed on the cells for 1 h. The volume was then raised to 10 ml, and infections were allowed to proceed for an additional 48 h, at which time the cells were harvested and total RNA was prepared. For infections performed in quiescent cells, MEFs were plated overnight in 10-cm culture plates at 50 to 60% confluency and then switched for 48 h to medium containing 0.2% FBS. Infections were performed as explained above, except that the cells were maintained quiescent for 24 h before being stimulated back into the cell cycle by the addition of complete medium.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were harvested in PBS, and whole-cell lysates were prepared by resuspending cell pellets in ice-cold RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1% Nonidet P-40), and incubating the suspension on ice for 20 to 30 min. For pRb Western blots, lysis buffer included phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM orthovanadate, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 80 μM cantharidin). Supernatant lysates were collected following high-speed centrifugation for 20 min at 4°C. Equal amounts of extract were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). Blocking was performed in 5% nonfat dry milk–1× TBST (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 125 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20). Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.5% nonfat dry milk–1× TBST, and the incubations proceeded for 30 min at room temperature, with the exception of pRb blots, where the primary antibody was incubated for 1 h. Washes were performed in 1× TBST for 5 to 10 min and repeated five times. Specific proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Science). Antibodies to IκBα (C-21), myogenin (M-225), cyclin D1 (R-124), cyclin A (C-19), MyoD (M-318), and p21 (C-19) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, pRb antibody was obtained from Pharmingen, cyclin D3, cdk4, and p27 antibodies were generous gifts of Y. Xiong (University of North Carolina).

Immunofluorescence.

All immunofluorescence experiments were performed directly in 12-well plates. Myoblasts were grown to subconfluency in GM and then switched to DM for 48 h. For 10T1/2 fibroblasts, cells were grown overnight in complete medium following transfections then switched to DM for 72 h. All steps were performed at room temperature. The cells were washed in PBS and fixed in a 2% formaldehyde–1× PBS solution for 30 min. They were permeabilized with 0.5% Nonidet P-40–1× PBS for 5 min and then blocked with horse serum (1:100) in PBS for 30 min. They were washed with PBS, incubated for 1 h with anti-skeletal myosin heavy chain (MY-32; Sigma) diluted 1:500 in 3% bovine serum albumin–1× PBS, washed three times with PBS, and incubated for 1 h in the dark with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma) diluted at 1:250. The cells were washed in PBS and photographed with an Olympus inverted microscope equipped with phase-contrast and UV illumination through an FITC filter. For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) staining, MEFs grown on glass coverslips were washed once in PBS, fixed for 5 min at room temperature with 100% cold methanol, washed again in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Following a PBS wash, the cells were treated for 10 min with 1.5 M HCl, washed four times with PBS, and incubated for 30 min with an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (1:10 dilution in 1% bovine serum albumin–PBS [Becton Dickinson]). After several washes in PBS, the cells were counterstained for 3 min with a 1-μg/ml solution of Hoechst dye 33258 (Sigma) in PBS. Following two additional washes in PBS, the coverslips were mounted on glass slides and examined on a Zeiss microscope.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Life Technologies). RNA samples were fractionated on an agarose gel and transferred overnight onto a nylon filter. The next day, RNA was cross-linked with a UV cross-linker (Stratagene). For detection of IκBα, Id-1, Hes-1, cyclin D3, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), mRNAs blots were hybridized in QuickHyb buffer supplemented with 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA as recommended by the manufacturer (Stratagene). For detection of cyclin D1 mRNA, blots were hybridized overnight at 42°C in 50% formamide–5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–1× PE (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.1% sodium pyrophosphate, 1% SDS, 0.25% polyvinylpyrrolidene, 0.25% Ficoll, 5 mM EDTA)–150 μg of salmon sperm DNA. All the probes were generated with a random-primed labeling kit (Life Technologies) in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP (NEN-Dupont). The DNA products were purified over micro-G-50 Sephadex columns (Life Technologies), boiled, and added to the hybridization mixture. Washes were performed twice in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 10 min at room temperature and then twice in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS for 20 min at 42°C for cyclin D1 detection and 65°C for detection of all other mRNAs.

RESULTS

Loss of NF-κB activity correlates with myogenic differentiation.

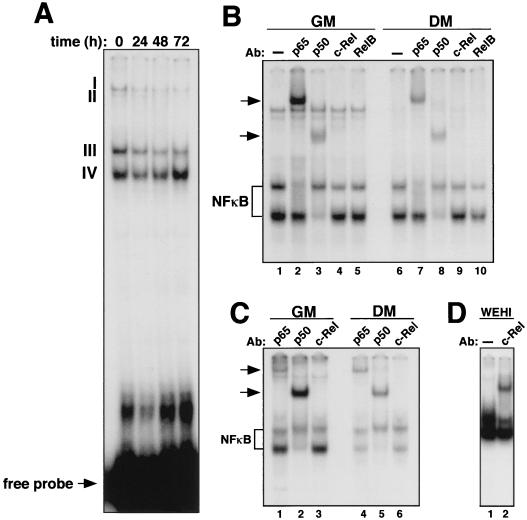

To analyze the role of NF-κB in cell growth control, we initiated our study by using the C2C12 myogenic differentiation model, since in this cell culture system the gene products involved in regulating terminal cell cycle arrest are largely known (39, 48, 71). First, we analyzed the relative levels and subunit composition of NF-κB/Rel complexes found in undifferentiated and differentiated C2C12 cell cultures. EMSAs performed with nuclear extracts prepared from C2C12 cells identified four potential NF-κB-containing complexes in proliferating myoblasts (Fig. 1A, lane 1). The levels of complexes I, II, and III decreased as cells became terminally differentiated (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 to 4). The level of complex IV initially decreased but was elevated 72 h following initiation of the differentiation process. EMSA supershifts performed to identify which Rel proteins were contained in these complexes revealed the presence of the p65 subunit in complex III and p50 in complex IV in both undifferentiated and differentiated cells (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 7 and 8). Although the antibody against p50 was not able to supershift complex III, the migration pattern of this complex nevertheless resembled that of the classical p50-p65 heterodimer. None of the antisera specific for NF-κB/Rel proteins caused a supershift in complexes I and II, suggesting that NF-κB is most probably not a component of these higher-molecular-weight complexes. To address whether these effects were specific to C2C12 cells, EMSA and supershift analyses were repeated with nuclear extracts prepared from primary myoblasts. As seen with the C2C12 cells, loss of p50 and p65 NF-κB DNA-binding activity was observed in primary myoblasts undergoing differentiation (Fig. 1C), indicating that a similar reduction of NF-κB may occur in naturally developing skeletal muscle.

FIG. 1.

Loss of NF-κB binding activity during myogenic differentiation. (A) Proliferating C2C12 myoblasts (GM) were induced to differentiate (DM), and at the indicated times nuclear extracts were prepared and EMSA was performed with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide containing an NF-κB-binding site. (B) C2C12 cells were maintained in GM or switched to DM for 72 h. Supershift EMSA was performed with nuclear extracts preincubated with either no antibody (lanes 1 and 6) or antisera specific for p65 (lanes 2 and 7), p50 (lanes 3 and 8), c-Rel (lanes 4 and 9), or RelB (lanes 5 and 10). NF-κB complexes containing p50 and p65 subunits are shown. (C) EMSA and supershift EMSA were performed as described above with nuclear extracts prepared from primary myoblasts undergoing differentiation. (D) Supershift EMSA was performed with nuclear extract prepared from WEHI-231 cells, preincubated either with no antibody or with an antiserum specific to the c-Rel subunit of NF-κB.

Earlier reports established that upregulated expression and increased DNA-binding activity of the NF-κB subunit c-Rel were associated with B-cell development (27). By EMSA, we were unable to detect c-Rel binding in skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 1B and C), suggesting that the role of NF-κB subunits, with respect to differentiation, may be tissue specific. To ensure that the oligonucleotide probe used in our EMSAs did not favor p65 binding, we tested it with extract prepared from the mature B-cell line WEHI-231, known to contain high levels of c-Rel-binding activity (42). Supershift analysis showed that the probe was readily bound by c-Rel in these cells (Fig. 1D), supporting the notion that, unlike what is found in lymphocytes, c-Rel binding is not induced during myogenic differentiation.

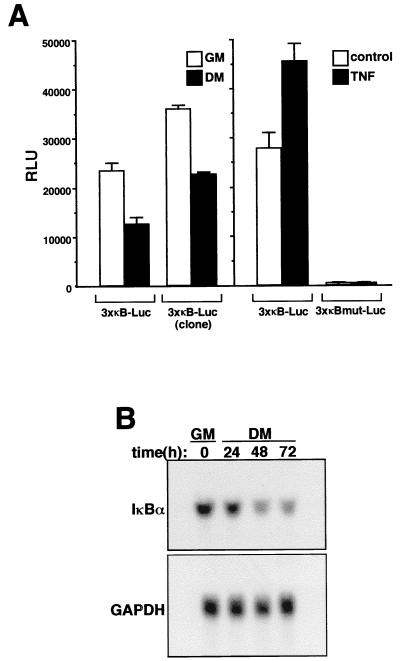

To determine whether loss of NF-κB binding activity correlated with its transactivation potential, a population of C2C12 cells were generated that stably integrated a luciferase reporter gene fused to three tandem repeats of the κB site from the MHC class I enhancer (3xκB-Luc). Upon differentiation of these cells, NF-κB transcriptional activity was reduced nearly 50% (Fig. 2A), a level which is likely to underrepresent the total loss of κB-dependent transcriptional activity, since not all C2C12 cells reach terminal differentiation under these culture conditions. Similar results were obtained when κB-dependent reporter activity was tested in an isolated clone undergoing differentiation (Fig. 2A). The functionality of the κB-dependent reporter was demonstrated by showing that the promoter was responsive to the NF-κB-activating cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) whereas a similar promoter containing a mutated version of the κB sites (3xκBmut-Luc) lacked basal activity and was unresponsive to cytokine treatment (Fig. 2A). To further investigate NF-κB transcriptional activity in myogenesis, Northern blot analysis was performed to probe for IκBα, whose transcription is known to be regulated by NF-κB (5). The results showed that a significant reduction in the level of IκBα mRNA was associated with differentiating C2C12 cells (Fig. 2B). Thus, the combined data from EMSAs, reporter assays, and Northern blotting confirmed that NF-κB activity, most probably represented by the classical, transcriptionally active p50-p65 heterodimer, is reduced in differentiating skeletal muscle cells.

FIG. 2.

Myogenic differentiation correlates with loss of NF-κB transactivation function. (A) C2C12 myoblasts stably containing a 3xκB-Luc reporter plasmid were propagated as either a mixed population or a clonal isolate. Cells were plated in triplicate overnight in 6-cm culture dishes, and on the following day they were maintained in GM or switched to DM for 48 h. At that time, cell extracts were prepared, and relative luciferase units were determined by normalizing to total protein (RLU). Promoter activities were also determined for 3xκB-Luc and 3xκBmut-Luc populations that were treated or not treated with 10 ng of TNF-α per ml for 24 h. (B) C2C12 cells were maintained in GM or differentiated in DM for up to 72 h. At the indicated times, total RNA was prepared and 10 μg of sample was used for Northern blot analysis. The blot was hybridized with an IκBα-specific probe, and RNA loading was normalized by stripping the blot and reprobing for GAPDH mRNA.

NF-κB functions as a negative regulator of myogenesis in the C2C12 model.

The results described above suggested a functional role for NF-κB in precursor myoblasts. To test this hypothesis, C2C12 cells were generated to express a mutant form of the IκBα inhibitor for which serines at positions 32 and 36 had been changed to alanines. The resulting protein (referred to as IκBα superrepressor, or IκBαSR) is no longer subject to phosphorylation and subsequent proteasome degradation following an NF-κB-activating stimulus and therefore functions as a potent and specific inhibitor of NF-κB activity (13). The absence of endogenous IκBα protein in IκBαSR-containing myoblasts (Fig. 3A), as well as the previously described sensitivity of IκBαSR-expressing cells or p65−/− cells to TNF-induced killing (9, 69, 72) (Fig. 3B), demonstrated that IκBαSR was functioning properly to block NF-κB activity. The inhibitory activity of the IκBαSR was confirmed by EMSA, which showed that only IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts were blocked in their ability to activate NF-κB in response to TNF treatment (data not shown). Parental, vector control, or IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts were examined for the rate at which they underwent differentiation. At 48 h following serum withdrawal, less than 10% of the parental or vector control cells had undergone differentiation, as determined by their myotube phenotype and by their ability to express the late differentiation marker, myosin heavy chain (Fig. 3C). In sharp contrast, nearly all the IκBαSR-expressing cells had become fully differentiated by this time (Fig. 3C). Similar enhanced rates of differentiation were observed in pooled clones of IκBαSR-containing cells, demonstrating that these effects were not due to clonal variations (Fig. 3C). An examination of a second temporally regulated myogenic differentiation marker, myogenin, demonstrated greatly accelerated expression of this myogenic transcription factor in C2C12-IκBαSR cells compared to vector control cells (Fig. 3D). These data suggested that NF-κB activity was required in proliferating myoblasts to block myogenic differentiation.

FIG. 3.

C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB activity have an accelerated rate of differentiation. (A) Whole-cell lysates were prepared from C2C12 parental, vector control, or IκBαSR proliferating myoblasts, and 50 μg of sample was used for Western blot analysis. IκBα and IκBαSR proteins were detected with an IκBα polyclonal antibody (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:1,500 dilution. The IκBαSR protein is FLAG tagged and therefore migrates at a slightly higher mobility compared to the endogenous protein. (B) IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts were seeded in triplicate overnight in 12-well plates, and the following day cells were treated with increasing concentrations of TNF-α for 48 h. Cell viability was scored by trypsinization and the trypan blue exclusion method. Cells not treated with TNF-α were designated 100% viable. (C) C2C12 parental cells, vector control, an IκBαSR clone, or five pooled IκBαSR clones were differentiated in DM for 48 h, at which time the cells were prepared for immunofluorescence to detect for the myosin heavy chain. (D) C2C12 vector control or IκBαSR cells were induced to differentiate in DM for up to 72 h. At the indicated times, lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed probing for myogenin expression. V (P) and I (P) denote myogenin expression from five pooled vector control or IκBαSR clones, respectively, that were differentiated for 48 h.

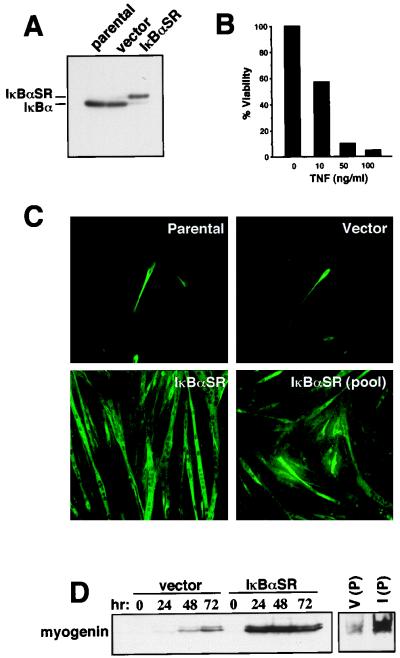

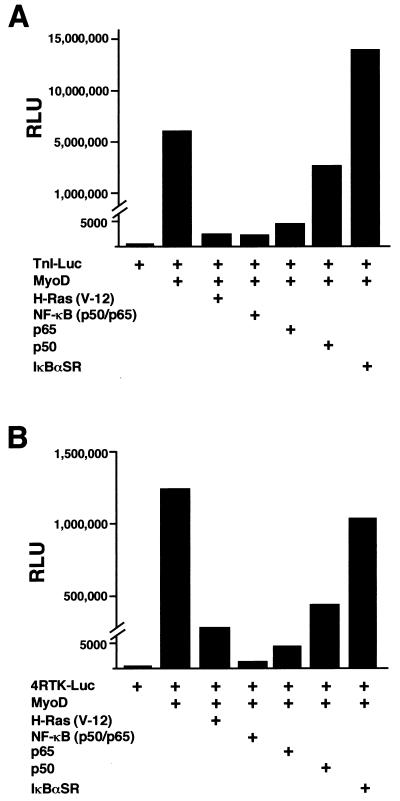

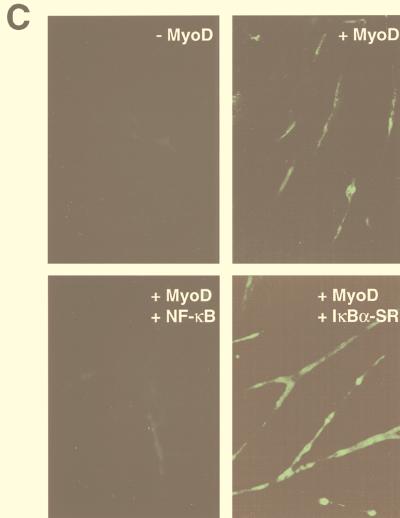

To verify that overexpression of IκBαSR in C2C12 cells did not introduce nonspecific effects leading to false interpretation of NF-κB function, we tested the ability of NF-κB to regulate the expression of a muscle-specific gene. One of the hallmark features of MyoD, as well as other members of the myogenic bHLH family, myogenin, myf5, and MRF4, is their ability to induce myogenic differentiation in nonmuscle cells (39). We therefore performed cotransfection experiments with murine embryonic C3H10T1/2 (10T1/2) fibroblasts and a reporter plasmid containing the troponin I enhancer and promoter (TnI-Luc), along with expression plasmids for MyoD, NF-κB, and/or IκBαSR. As expected, MyoD strongly activated the troponin I reporter when cells were placed in differentiation conditions (Fig. 4A). However, coexpression of the p50 and p65 NF-κB subunits strongly repressed the activation by MyoD, at levels comparable to those for oncogenic H-Ras, a known potent negative regulator of myogenesis (37, 40, 49). Viability assays determined that the reduction in MyoD transactivation by NF-κB was not due to cell death resulting from transfection conditions (data not shown). Similar inhibition levels were produced when the p65 subunit, but not p50, was cotransfected along with MyoD, suggesting that the transcriptional activation function of NF-κB is required to mediate this regulation. It was possible that expression of NF-κB subunits sequestered a cofactor required for MyoD transcriptional function. Therefore, we asked whether inhibition of NF-κB function would enhance MyoD transcriptional activity. Expression of IκBαSR enhanced MyoD transcriptional activation of troponin I over that of MyoD alone (Fig. 4A), reaffirming the notion that NF-κB functions as an inhibitor of differentiation. We also observed that expression of IκBαSR partially overcame the ability of Ras to inhibit MyoD transcriptional activity (data not shown), confirming that NF-κB is a Ras-responsive transcription factor which also can mediate antidifferentiation. Similar results to the ones described above were obtained when transfections were repeated with a reporter plasmid containing four E-box sites from the muscle creatine kinase enhancer (4RTK-Luc) (Fig. 4B), which is also known to be strongly regulated by myogenic bHLH proteins (39). These results argue that negative regulation on myogenesis by NF-κB is not specific to the troponin gene. As an additional approach to assay the regulatory potential of NF-κB on differentiation, cotransfections with MyoD and NF-κB subunits were performed with 10T1/2 fibroblasts and analyzed for their effects on myotube formation and myosin heavy-chain expression. As can be seen in Fig. 4C, the expression of MyoD in 10T1/2 cells caused the formation of small myotubes 72 h following serum withdrawal but addition of NF-κB was sufficient to completely abolish this myogenic event. In contrast, the expression of IκBαSR with MyoD enhanced both the overall number (quantitatively approximated to be threefold over that of MyoD alone) and size of myotubes formed in the culture wells (Fig. 4C). These findings correlated strongly with the reporter assay data and confirmed that NF-κB functions as a negative regulator of myogenic differentiation in vitro.

FIG. 4.

NF-κB inhibits MyoD-induced myogenesis in 10T1/2 fibroblasts. Cells were maintained in growth medium containing 15% FBS and differentiated in DM. The cells were seeded in triplicate overnight in 6-cm dishes, and the following day, cotransfections were performed with Superfect (Qiagen). DNA consisted of 1 μg of a troponin-I-Luc reporter plasmid (TnI-Luc) (A) or 1 μg of the 4RTK-Luc plasmid (B), along with 0.25 μg of an expression plasmid for MyoD alone or in combination with 0.5 μg of expression plasmids for either the activated form of oncogenic ras (H-ras V-12), p65, p50, or 1 μg of IκBαSR. DNA was standardized to 2.5 μg by the addition of Bluescript plasmid (Stratagene). Cells were maintained in growth medium for 24 h following transfections and then switched to DM for 48 h, at which time cell extracts were prepared and relative light units (RLU) were determined, by normalizing values to total protein. (C) For immunofluorescence analysis, 10T1/2 cells were seeded overnight and the next day similar transfections were performed as described above, except that one-third of the amount of DNA was used. At 24 h following transfections, the cells were switched to DM for 72 h, at which time the cells were fixed and probed for the myosin heavy chain. To score for the number of myotubes formed, cells expressing myosin were counted and averaged from a minimum of 10 randomly selected fields.

NF-κB inhibits C2C12 myogenesis through its growth-promoting activity and regulation of cyclin D1.

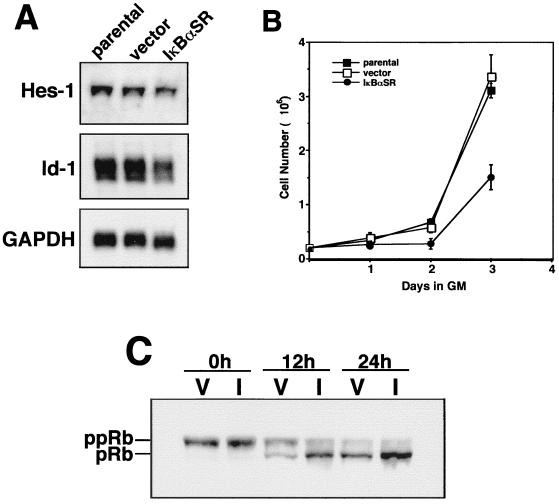

To determine the mechanism by which NF-κB regulated myogenesis in vitro, we first examined whether NF-κB had any effect on the expression of Id-1 or Hes-1, which are known inhibitors of differentiation (12, 55). Northern analysis performed with mRNA isolated from proliferating C2C12 parental, vector control, or IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts revealed that the steady-state levels of Hes-1 was only slightly altered whereas Id-1 was more strongly altered in cells lacking NF-κB activity (Fig. 5A). This result may indicate that these genes could be involved in NF-κB-mediated inhibition of myogenic differentiation. Relevant to the regulatory mechanism of NF-κB was that C2C12-IκBαSR cells maintained in growth medium exhibited a substantial increase in cell doubling time compared to parental or vector control cells (Fig. 5B). Since successful progression of myogenic differentiation is highly dependent on the ability of cells to irreversibly exit the cell cycle in the G1 state (71), we asked whether the effect on cell growth as a result of the absence of NF-κB activity translated to changes in cell cycle progression. Exit from cell cycle was assessed by immunoblot analysis probing for the phosphorylation status of pRb. The results showed that while no obvious differences in pRb states were observed in either vector control or IκBαSR cells maintained in fresh growth medium (t = 0 h), once cells were induced to differentiate (t = 12 and 24 h) pRb hypophosphorylation occurred much faster in IκBαSR cells than in control cells (Fig. 5C). These data imply that in immortalized C2C12 cells, inhibition of NF-κB accelerates the rate at which cells exit the cell cycle.

FIG. 5.

C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB exhibit a growth defect and changes in pRb phosphorylation. (A) Total RNA was prepared from C2C12 parental, vector control, or IκBαSR proliferating myoblasts, and Northern analysis was performed to detect the expression of Hes-1 or Id-1 genes. (B) C2C12 parental, vector control, or IκBαSR myoblasts were plated in triplicate in 10-cm plates and maintained in GM for 3 days. Every 24 h, the total cell number was determined by trypsinization and trypan blue exclusion. (C) C2C12 vector control (V) or IκBαSR cells (I) were induced to differentiate for up to 24 h. At the indicated times, cell lysates were prepared with lysis buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors and Western blotting was performed to probe for the hypo- and hyperphosphorylated forms of Rb with a monoclonal antibody (14001A; Pharmigen).

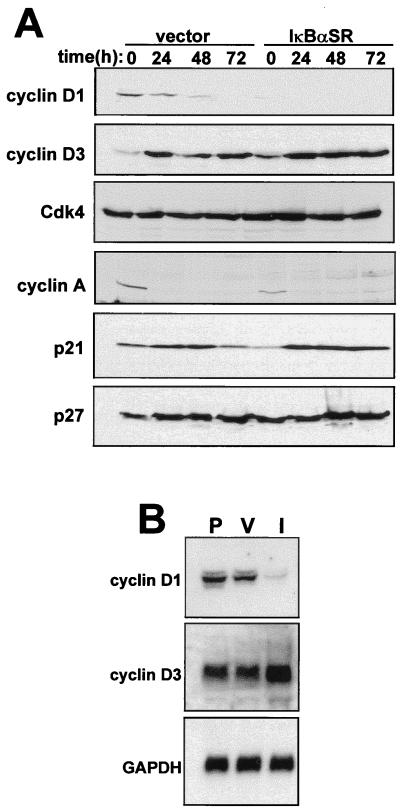

The above finding prompted us to search for other cell cycle regulatory factors that function upstream of pRb and that could potentially be regulated by NF-κB. Immunoblotting results showed that under proliferating conditions, IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts exhibited a striking reduction in cyclin D1 levels compared to vector control cells (Fig. 6A). In addition, cyclin D1 levels decreased more rapidly in differentiating IκBαSR cells than in control cells. Potential regulation by NF-κB for other cell cycle regulators, cyclin D3, cyclin A, and p21, was observed but was less dramatic than the effect on cyclin D1 and may therefore be due to secondary effects of changes on cyclin D1. Although basal levels of p21 were reduced in C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB (Fig. 6A), inhibition of NF-κB did not block the accumulation of p21, which is associated with myogenic differentiation (29, 30). The lack of any significant regulation of cdk4, as well as for the cdk inhibitor protein p27, also indicated that effects of NF-κB on cyclin D1 expression were specific. Consistent with immunoblotting results, steady-state levels of cyclin D1 mRNA were also significantly lower in proliferating IκBαSR-expressing myoblasts than in either parental or vector control cells (Fig. 6B). In comparison, we detected only a slight effect on cyclin D3 mRNA expression in the NF-κB-inhibited cells, consistent with observations showing that cyclin D3 levels increase during skeletal muscle differentiation (51). These results therefore demonstrate that NF-κB is a specific regulator of cyclin D1.

FIG. 6.

C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB are downregulated for cyclin D1 protein and mRNA. (A) C2C12 vector control or IκBαSR cells were differentiated in DM for up to 72 h. At the indicated times, whole-cell lysates were prepared and 50 μg was used in Western blot analyses to probe for various cell cycle proteins. (B) Total RNA was prepared from proliferating parental (P), vector control (V), or IκBαSR (I) myoblasts, and 10 μg of sample was used in Northern blotting to probe for cyclin D1 or cyclin D3 mRNA.

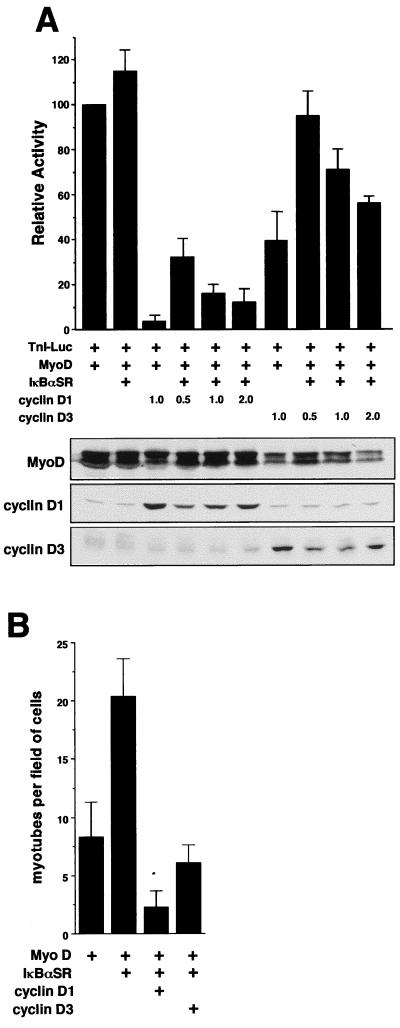

As shown in Fig. 6A and consistent with previous reports (51, 64), downregulated expression of cyclin D1 correlates with myogenic differentiation. One mechanism by which cyclin D1 is thought to function as a negative regulator of this cellular process is by blocking the transactivation function of MyoD (51, 64). Indeed, in agreement with these previous reports, cotransfections in 10T1/2 fibroblasts showed that while cyclin D1 strongly blocked the ability of MyoD to activate the troponin I gene, cyclin D3 was only partially inhibitory toward MyoD (Fig. 7A). To examine whether NF-κB inhibits myogenesis through its regulation of cyclin D1, NF-κB activity was inhibited in 10T1/2 cells through expression of IκBαSR and cyclin D1 was reexpressed to determine if the block on MyoD transcriptional function could be restored. The inhibitory potential of the IκBαSR plasmid in these cells was confirmed on an NF-κB-responsive promoter (data not shown). The results showed that increasing the amounts of the cyclin D1 expression plasmid could restore the inhibition of MyoD activity in cells where NF-κB was inhibited (Fig. 7A). In comparison, similar cotransfections with the cyclin D3 expression vector were significantly less effective at inhibiting MyoD function. Importantly, similar results were obtained when myogenesis was assessed by scoring for myotube formation (Fig. 7B), demonstrating that these effects were not specific to the troponin I gene.

FIG. 7.

NF-κB inhibits MyoD transactivation function through the regulation of cyclin D1. (A) 10T1/2 fibroblasts were seeded in triplicate overnight in 6-cm culture dishes, and the next day cotransfection was performed with DNA consisting of 1 μg of the troponin-I reporter plasmid (TnI-Luc) and 0.25 μg of a MyoD expression plasmid, along with either 0.25 μg of an IκBαSR expression plasmid or the indicated amounts of cyclin D1 or cyclin D3 expression plasmid. DNA was normalized by the addition of Bluescript plasmid (Stratagene). Transfected cells were maintained in growth medium overnight and on the following day were switched to DM for 48 h, at which time extracts were prepared and a luciferase assay was performed. The level of troponin-I activation by MyoD alone was set to a value of 100. (Below) To verify the expression of proteins, parallel transfections were performed and immunoblot analysis was performed to probe for MyoD, cyclin D1, and cyclin D3. (B) Similar transfections were performed in 10T1/2 fibroblasts with the following amounts of expression plasmids: 0.25 μg of MyoD, 1 μg of IκBαSR, and 2 μg of cyclin D1 or cyclin D3. The cells were differentiated as described above for 72 h, at which point myogenesis was quantitated by counting myotubes from a minimum of 10 fields of cells.

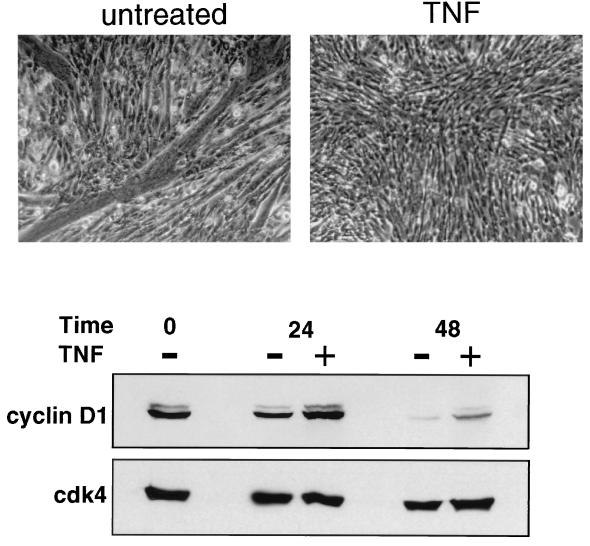

To further explore whether cyclin D1 is involved in NF-κB regulation of myogenesis, NF-κB was activated by TNF-α while C2C12 myoblasts were induced to undergo differentiation. The results showed that TNF treatment almost completely repressed the ability of C2C12 cells to form myotubes, again supporting the claim that NF-κB functions as a negative regulator of myogenesis (Fig. 8). In addition, while the levels of cyclin D1 were diminished in untreated differentiating cells, cyclin D1 was stabilized in differentiating C2C12 cells activated for NF-κB. Although it is possible that these effects of TNF occur independently of NF-κB activation, this result, taken together with previous data, strongly suggests that one mechanism by which NF-κB inhibits skeletal muscle differentiation is through the regulation of cyclin D1 expression.

FIG. 8.

TNF-α inhibits C2C12 myogenesis and stabilizes cyclin D1. C2C12 cells were induced to differentiate in the absence or presence of 20 ng of TNF-α per ml. Cytokine addition was repeated at 6 h and every additional 12 h after the induction of differentiation. At 72 h, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde, and photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. In parallel treatment cultures, cells were harvested at 24 and 48 h and whole-cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis. A 50-μg portion of total protein was fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotting was performed to probe for cyclin D1. The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed for cdk4, used as an internal control.

NF-κB is a direct transcriptional activator of cyclin D1.

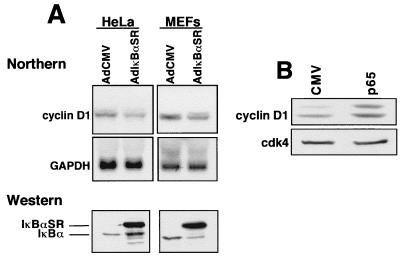

The use of the C2C12 myogenesis model allowed us to demonstrate that NF-κB regulates cyclin D1 expression. Next, we were interested in determining whether this regulation was tissue specific and at what level it was controlled. To address the first of these points, an adenoviral delivery system was used to transiently overexpress IκBαSR in HeLa cells and MEFs. Northern analysis showed that, similar to what was seen in C2C12 cells stably expressing IκBαSR, transient inhibition of NF-κB activity led to a decrease in steady-state levels of cyclin D1 mRNA (Fig. 9A). This result demonstrated that this regulation was therefore not unique to skeletal muscle cells and, perhaps equally important, did not result from a clonally selectable process. Conversely, transfections in fibroblasts with a plasmid expressing the p65 subunit of NF-κB led to increased levels of endogenous cyclin D1 (Fig. 9B), thus underscoring the specificity of the IκBαSR protein and demonstrating that expression of p65 is sufficient to induce cyclin D1 expression.

FIG. 9.

Regulation of cyclin D1 is specific to NF-κB occurring in multiple cell types. (A) HeLa cells or MEFs were infected with adenovirus containing either the IκBαSR or empty vector (AdCMV) at a multiplicity of infection of 50 or 200, respectively. Total RNA was prepared 48 h postinfection, and Northern analysis was performed to detect cyclin D1 mRNA expression. Western blot analysis with an IκBα-specific antibody is shown to demonstrate the expression of the IκBαSR in HeLa cells and MEFs by using the adenovirus delivery system. (B) Fibroblasts were transfected with either empty vector or an expression plasmid expressing the p65 subunit of NF-κB. The following day, cells were switched to serum-deprived conditions for a 48-h period. Subsequently, whole-cell extracts were prepared and 50 μg was used in immunoblot analysis probing for cyclin D1. The loading efficiency was normalized by reprobing the blot for cdk4 expression.

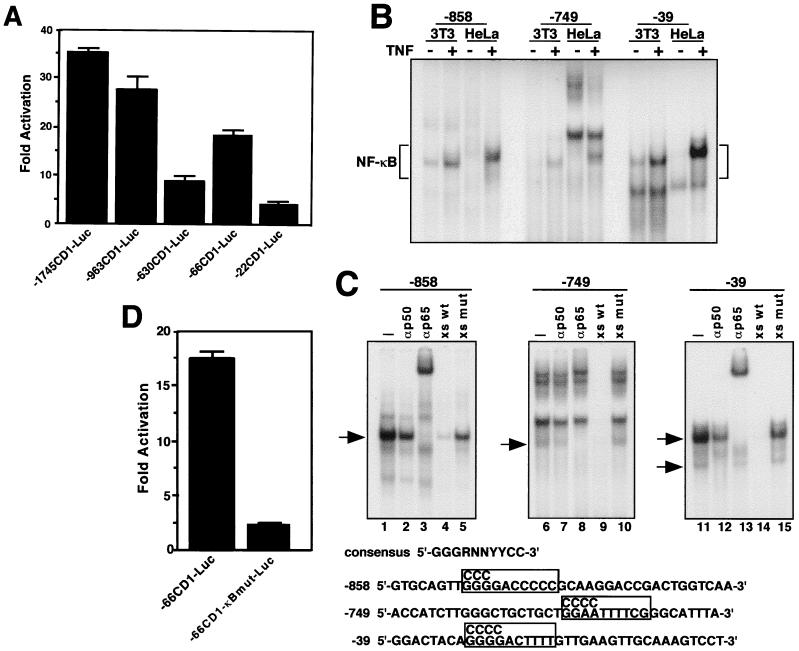

Second, to investigate the mechanism of this regulation, cotransfections were performed with reporter plasmids containing different lengths of the human cyclin D1 promoter and an expression plasmid for p65. These experiments showed that p65 strongly activated cyclin D1 gene expression and that this regulation mapped to regions from −963 to −630 and −66 to −22 within the promoter (Fig. 10A). Transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 promoter was also observed when c-Rel was expressed in these cells (data not shown), indicating that this regulation is not specific to the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Examination of the sequence from the human cyclin D1 promoter (47) identified potential NF-κB-binding sites at positions −858, −749, and −39 that matched the NF-κB consensus binding sequence, GGG(G/A)NNYYCC, and that mapped to the regions we had identified to be regulated by p65. Oligonucleotides to these sites were generated and tested by EMSA to determine whether NF-κB binding occurred. With nuclear extracts prepared from both NIH 3T3 and HeLa cells, complexes were formed at all three sites (Fig. 10B). TNF treatment, which activates nuclear translocation of NF-κB, displayed increased complex formation, providing greater evidence that NF-κB was the component bound to these sites. Supershift analysis determined that NF-κB complexes were predominantly represented by the p65 subunit and that the −39 site contained both the p50 homodimer and p50-p65 heterodimer complexes, since at this site both antibodies either supershifted or blocked complex formations (Fig. 10C). Furthermore, oligonucleotide competition analysis established that the binding of these complexes was specific to κB sites (Fig. 10C). Finally, site-directed changes made in the NF-κB site located at position −39, within the −66CD1-Luc reporter plasmid, demonstrated the requirement of this regulatory site for cyclin D1 transcriptional activation relative to expression of the NF-κB p65 subunit (Fig. 10D). Taken together, these data conclusively demonstrate that NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 occurs at the transcriptional level mediated by direct binding of NF-κB to potentially multiple regions within the cyclin D1 promoter.

FIG. 10.

NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 occurs at the transcriptional level. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were plated in triplicate in 12-well plates. Transfections were performed on the following day with Lipofectamine reagent (Life Technologies) mixed with DNA consisting of 0.2 μg of reporter plasmids containing various 5′ deletions of the human cyclin D1 promoter, along with 0.15 μg of a p65 expression plasmid. DNA remained on the cells for 3 h in serum-free medium, and the cells were then switched for 48 h to complete medium containing 10% calf serum, at which time the luciferase activity was determined. Values were normalized to basal levels of promoter activity obtained by transfecting cyclin D1 promoter constructs in the absence of p65. (B) EMSAs were performed with nuclear extracts prepared from either NIH 3T3 cells or HeLa cells treated (+) or not treated (−) with TNF-α for 30 min. Putative NF-κB-binding sites, located at positions −858, −749, and −39 in the human cyclin D1 promoter, are indicated within the oligonucleotide sequences used for EMSAs. (C) Supershift EMSAs were performed with nuclear extracts prepared from HeLa cells treated with TNF, which were preincubated either with no addition (lanes 1, 6, and 11) or with addition of antisera specific for p50 (lanes 2, 7, and 12), or the p65 subunit (lanes 3, 8, and 13). Arrows denote p65-containing complexes. For competition EMSAs, extracts were preincubated with either a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides containing wild-type (xs wt) NF-κB-binding sites (lanes 4, 9, and 14), or a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides containing mutations in the NF-κB sites (xs mut) (lanes 5, 10, and 15). The mutations are shown in the boxed regions above the NF-κB-binding sites. (D) The same mutation at position −39 was made in the NF-κB-binding site within the −66CD1-Luc reporter plasmid. Both the wild-type and mutant (−66CD1-κBmut-Luc) reporter plasmids were separately cotransfected along with a p65 expression plasmid in NIH 3T3 cells under the same transfection conditions as described for panel A.

NF-κB is required in early G1 for cyclin D1 activation and progression into S phase.

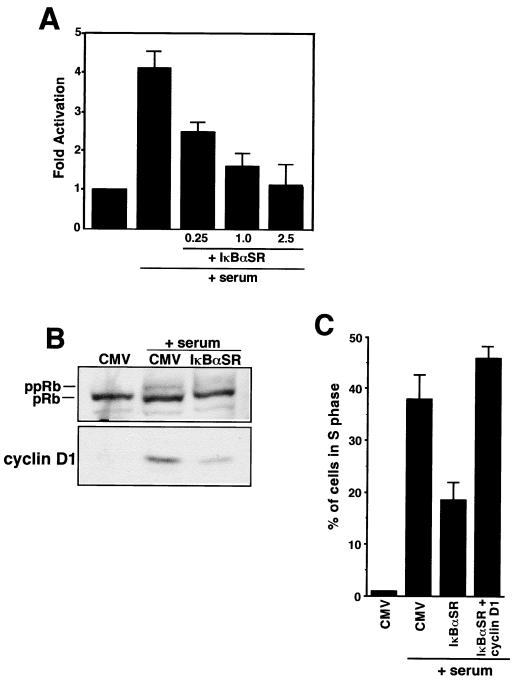

Having established that cyclin D1 is a novel transcriptional target of NF-κB and provided evidence to show how this regulation is important for controlling the differentiation of skeletal muscle cells, we focused the last part of our study on examining the relevance of this regulatory mechanism to cell cycle progression and cell growth. Cyclin D1 was originally identified as a suppressor of G1 arrest in yeast cells and as a gene that is inducible in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (44, 76). The expression of cyclin D1 in G1 is important for cell cycle progression (60, 61), and results demonstrating that acceleration into S phase by cyclin D1 is greater for synchronized cultures emerging from quiescence than for asynchronous cycling cells suggest a specialized role for this D-type cyclin in the G0/G1 transition (53). Interestingly, earlier results from our laboratory showed that NF-κB was strongly activated when growth-arrested fibroblasts were stimulated by serum to re-enter cell cycle (6). This finding prompted us to investigate whether NF-κB was required for cyclin D1 induction in cells reinitiating cell cycle.

Since differentiated C2C12 cells are not capable of reinitiating a cell cycle, we instead turned to the use of diploid fibroblasts. Cotransfections were performed in quiescent fibroblasts with a reporter plasmid containing the cyclin D1 promoter and the IκBαSR expression plasmid, and cells were subsequently stimulated back into the cell cycle with the addition of serum. The results showed that in the absence of the IκBαSR plasmid, cyclin D1 promoter activity was induced approximately fourfold in response to mitogen addition (Fig. 11A). In contrast, inhibition of NF-κB by IκBαSR expression blocked this induction in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that NF-κB is required for cyclin D1 transcriptional activation in early G1. To examine whether NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 was also important for the G1-to-S progression, quiescent MEFs were infected with adenovirus containing either empty vector (CMV) or IκBαSR and cells were allowed to reinitiate the cell cycle. G1-to-S progression was first assessed by examining the phosphorylation status of pRb. The result of this experiment showed that cells lacking NF-κB contained a substantially lower level of hyperphosphorylated pRb than did CMV control cells (Fig. 11B). Importantly, the decrease in pRb hyperphosphorylation in these cells correlated with a marked reduction of cyclin D1, supporting the notion that the Rb protein is a direct target of the cyclin D1-cdk4 complex. By using similar infection conditions, MEFs lacking NF-κB activity were also shown to be significantly impaired for entry into S phase, as assessed by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 11C). Importantly, the defect in S-phase entry in these cells could be restored by addition of cyclin D1, arguing that NF-κB activation of cyclin D1 is important for G1-to-S progression.

FIG. 11.

Requirement for NF-κB activity in the early G1 phase of the cell cycle. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were made quiescent by being switched for 48 h from complete medium containing 10% serum to medium containing 0.25% calf serum. Serum-deprived cells were cotransfected either with a cyclin D1 promoter reporter plasmid alone (−963CD1-Luc) (2.5 μg) or in combination with indicated amounts of IκBαSR plasmid. The cells were maintained in quiescence or switched to complete medium to induce cyclin D1 transcription and reentry into the cell cycle. Extracts were prepared, and relative luciferase activity was determined by standardizing to total cellular protein. (B) MEFs were made quiescent by culturing cells in 0.1% FBS for 48 h. The cells were then infected under serum-deprived conditions with adenovirus containing either empty vector (CMV) or IκBαSR at an MOI of 200. At 24 h postinfections, MEFs were either maintained under serum-deprived conditions or induced to reenter the cell cycle by the addition of 10% FBS. Whole-cell lysates were prepared 24 h later, and immunoblot analysis was performed to probe for both pRb and cyclin D1 (under these culture conditions, we determined that pRb hyperphosphorylation in MEFs is maximally detectable between 20 and 24 h following serum stimulation). (C) Subconfluent MEFs were grown on coverslips overnight and were rendered quiescent on the following day. Cells were infected with either control adenovirus (CMV), IκBαSR, or a combination of IκBαSR and cyclin D1 viruses (both at a multiplicity of infection of 200). At 24 h following infections, the cells were maintained quiescent or switched for 12 h to growth medium containing 10% serum, at which point the medium was supplemented with 100 μM BrdU (Sigma) for an additional 10 h. The cells were fixed and prepared for immunofluorescence analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of cells in the S phase was calculated by determining the number of BrdU-positive cells with respect to the total number of cells in a given field.

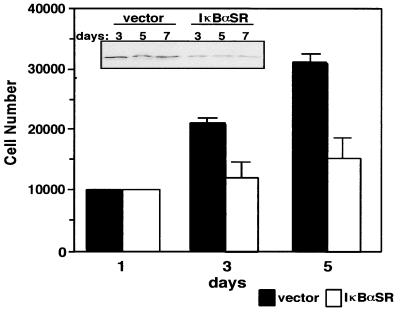

Finally, based on the above findings, we asked whether NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 was a relevant mechanism involved in the proliferation of primary fibroblasts. To investigate this, we used a retrovirus delivery system to stably generate a mixed population of MEFs expressing either empty vector or the IκBαSR protein. Again, immunoblot analysis showing that endogenous levels of IκBα were downregulated in IκBαSR-expressing fibroblasts (as shown in Fig. 3A) confirmed that NF-κB activity was effectively blocked (data not shown). When growth rates were monitored, the results showed that over an extended number of passage doublings, fibroblasts devoid of NF-κB activity exhibited a significant defect in cellular proliferation (Fig. 12). Importantly, NF-κB inhibition in these cells again led to a persistent decrease in the levels of cyclin D1 (Fig. 12, inset), suggestive that NF-κB growth-promoting activity is tightly coupled to its transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1.

FIG. 12.

NF-κB is required for proper cellular proliferation in primary fibroblasts. Early-passaged MEFs were infected by retrovirus either harboring empty vector or the IκBαSR. At 2 days following infection, the cells were placed on a 4-day drug selection with 400 μg of G418 per ml. A mixed population of selected cells was then seeded in triplicate in either 12-well plates or 10-cm dishes. Cells seeded in 12-well plates were trypsinized every 24 to 48 h, and cell numbers were determined by the trypan blue exclusion method. Cells seeded in 10-cm dishes were collected on days 3, 5, and 7, and lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis detecting for cyclin D1 (inset).

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to gain an insight into how NF-κB participates in regulate cell growth and differentiation. To examine this, we first used a skeletal differentiation model, since many of the genes that regulate this cellular process have been elucidated. We discovered that in this system NF-κB activity is reduced as cells undergo differentiation. In myoblasts generated to lack NF-κB activity, the differentiation was accelerated, suggesting that NF-κB plays a role in proliferating myoblasts to inhibit their differentiation. This claim was supported in transfection experiments performed with 10T1/2 fibroblasts, where we demonstrated that the inhibitory action of NF-κB was as potent as oncogenic ras and inhibition of myogenesis was specific to the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Our observation that myoblasts lacking NF-κB activity increased their cell-doubling time and, upon receiving a differentiation signal, appeared to exit the cell cycle faster than control cells did, led us to conclude that NF-κB regulates cyclin D1 expression. Regulation of this cyclin was shown to be one mechanism by which NF-κB acted as a negative regulator of myogenesis. We extended our study to examine at what level cyclin D1 regulation by NF-κB occurred. The results showed that the p65 subunit of NF-κB was a potent transcriptional activator of the cyclin D1 gene. In addition, we found that NF-κB bound the cyclin D1 promoter at multiple sites, and for at least the −39 site, we showed by site-directed mutagenesis that NF-κB sequences are required for transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 promoter. Furthermore, we demonstrated that NF-κB activity is required for both cyclin D1 transcriptional activation and S-phase entry, suggesting an important role for NF-κB in early G1. Finally, we showed that similar to immortalized C2C12 cells, primary fibroblasts also lacking NF-κB activity exhibited reduced proliferation rates in conjunction with lower cyclin D1 levels, arguing that the regulation of this cyclin by NF-κB is important for proper cell growth control. While our manuscript was in preparation, Hinz et al. reported similar findings that NF-κB transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1 is necessary in G1-to-S progression (33). Below, we discuss in greater detail the implications of our findings with respect to the function of NF-κB in cellular differentiation, the cell cycle, and oncogenesis.

A role for NF-κB as a negative regulator of differentiation.

NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 gene expression was revealed by examining the role of NF-κB in a myogenic differentiation model. Results obtained from analyses which included EMSAs, reporter assays, generation of C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB activity, and transfections in 10T1/2 fibroblasts (Fig. 1 to 4), confirmed that NF-κB functions, at least in vitro, as a negative regulator of skeletal muscle differentiation. Our results also show that this regulation requires the transcriptional activation function provided by the p65 component of NF-κB. One point, which will be addressed in future experiments, is whether the p65 subunit also functions as a negative regulator of myogenesis in vivo. Such an experiment may be difficult to perform since mice with deletions of the p65 subunit die in utero (11) and since functional redundancy is most likely to exist among NF-κB family members. In addition, genes such as pRb and p21WAF1/CIP1, considered important in regulating skeletal myogenesis in vitro (29, 30), are not required for normal skeletal development in the animal (71). It is also noteworthy that defects in skeletal muscle development were not indicated in cyclin D1 knockout animals (62), underscoring the complexity of this cellular process. Other reports support a role for NF-κB in regulating cellular differentiation. For instance, the induction of c-Rel gene expression and DNA-binding activity in mature B cells implicates this NF-κB subunit in the development of hematopoietic cells (27). Data has also shown that mice with deletions of both p50 and p52 subunits exhibited defects in osteoclast development (25, 35). More recently, the inhibition of NF-κB activity in keratinocytes, using a similar IκBα transdominant mutant to that used in the present study, prevented the maturation process of these cells (57). In addition, the inhibition of NF-κB activity in the proliferative zone of the developing avian limb bud led to impaired growth of this tissue (15, 36). These data, in conjunction with our results, suggest that NF-κB functions in multiple tissues to regulate their differentiation. We speculate that whether NF-κB promotes or represses cellular differentiation most probably depends on which specific homo- or heterodimer forms of this transcription factor are represented during the development of a particular tissue and on cell type differences which control distinct transcriptional responses.

Mechanisms of NF-κB inhibition of myogenesis.

C2C12 cells containing the IκBαSR, and therefore devoid of NF-κB activity, were observed to be accelerated in their differentiation program (Fig. 3). These cells also exhibited significant reductions in their proliferation rates and, upon receiving a differentiation signal, appeared to show an acceleration in the rate at which they exited the cell cycle (Fig. 5). The defect in the growth of C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB activity most probably contributes to their ability to rapidly exit cell cycle. Since terminal cell cycle arrest is known to be coupled to myogenic transcription (39), we reasoned that the ability of C2C12-expressing IκBαSR cells to undergo rapid differentiation is due to the fact that these cells are capable of early G1 arrest. These results therefore indicate that one mechanism by which NF-κB inhibits differentiation is through its growth-promoting activity.

Our analysis of cell cycle markers identified the downregulated expression of cyclin D1 in C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB activity. Since cyclin D1 is an important regulator of cell cycle progression in many cell types, our results suggest that the premature cell cycle arrest observed in differentiating C2C12-expressing IκBαSR cells is derived from its lower levels of cyclin D1. These results further imply that the ability of NF-κB to inhibit myogenic differentiation through its growth-promoting activity is derived directly from its regulation of cyclin D1 expression. This hypothesis is supported by previous findings that ectopic expression of cyclin D1, in association with its catalytic partners cdk4 and cdk6, inhibits myogenesis (64). It should be noted, however, that in these studies the inhibition of myogenesis was assessed by the ability of cyclin D1 to block MyoD transactivation function of muscle-specific genes. In addition, evidence has been presented showing that cyclin D1 inhibition of the transactivation function of MyoD is independent of the activity of this cyclin to phosphorylate pRb (63). These data therefore suggest that the ability of cyclin D1-cdk complexes to inhibit skeletal muscle differentiation is a process that may be uncoupled from the ability of these kinase complexes to promote cell cycle progression. Based on this assumption, it is possible that NF-κB inhibits myogenesis by at least two distinct mechanisms: (i) by promotion of growth and cell cycle progression independent of cyclin D1 regulation, and (ii) by positive regulation of cyclin D1, which functions to block the activities of myogenic transcription factors (as demonstrated in Fig. 7).

Elucidation of a novel transcriptional target of NF-κB.

Part of our analysis in this study was to identify whether NF-κB directly regulated cyclin D1 gene expression. The results of cyclin D1 promoter-reporter assays and EMSAs confirmed that NF-κB regulation of cyclin D1 was mediated at the transcriptional level by authentic NF-κB binding in at least three sites, −858, −749, and −39 (Fig. 10). Mutational analysis demonstrated that NF-κB binding to the −39 site was important for cyclin D1 transcriptional regulation. These results therefore indicate that NF-κB transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1 occurs directly via binding to multiple sites within the promoter region. To further explore this mechanism, we have attempted to address whether NF-κB, on its own, can induce cyclin D1 mRNA expression when quiescent fibroblasts are stimulated back into the cell cycle. However, Northern analysis indicated that in the absence of ongoing protein synthesis, the cyclin D1 mRNA is highly labile (data not shown), making our interpretation with respect to NF-κB technically limiting. Therefore, although our results indicate quite clearly that NF-κB transcriptionally activates cyclin D1, we cannot exclude the possibility that other transcription factors are required that function in a synergistic fashion with NF-κB to obtain full transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 gene. Support for this latter hypothesis comes from earlier studies demonstrating that cyclin D1 is transcriptionally regulated separately by the AP-1 and Ets transcription factor complexes (1, 32), both of which are known to physically associate with NF-κB (8, 67). It is clear that the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of the cyclin D1 gene is complex and requires further detailed experimentation.

Establishing a role for NF-κB in early G1 relative to cell growth.

Several reports have described an association with NF-κB activation and the early G1 phase of the cell cycle. Previously, we found that NF-κB was strongly activated when quiescent fibroblasts were stimulated by serum addition to reenter the cell cycle (6). Others have described a rapid NF-κB DNA-binding activity following partial hepatectomy, when hepatocytes progress in the cell cycle from G0 to G1 (17, 24). Absence of NF-κB activity has also been correlated with defects in early G1, which contributed to a failure of resting B cells to proliferate in response to an activating stimulus (28). The results in this report showing that NF-κB is a transcriptional regulator of cyclin D1 now provide a molecular mechanism with which we can better understand the role of this transcription factor in the early G1 phase of the cell cycle. Based on our findings that cell cycle progression was not affected in cycling immortalized C2C12 cells lacking NF-κB (Fig. 5 and data not shown), we believe that the relevance of cyclin D1 regulation by NF-κB may be more meaningful in cells either reentering or exiting the cell cycle. This hypothesis is supported by results obtained with C2C12 cells, where a defect in cell cycle exit was associated with cells lacking NF-κB activity. Support also comes from our analysis of fibroblasts, where we demonstrated that upon progression from G0 to G1 to S, NF-κB activity is required for cyclin D1 transcriptional activation, pRb hyperphosphorylation, and proper S-phase entry (Fig. 11). These latter findings are consistent with a recent report showing the requirement of NF-κB activity during the G1-to-S phase transition, in conjunction with its regulation on cyclin D1 expression (33). The complementary data of both studies, including our additional results showing that embryonic fibroblasts lacking NF-κB activity also exhibit a severe growth defect correlating with reduced levels of cyclin D1 (Fig. 12), implicates the regulation of cyclin D1 as a mechanism to explain how NF-κB promotes cell growth. This hypothesis is consistent with the role of cyclin D1 as a regulator of cell growth, since mice lacking cyclin D1 display reduced body size and exhibit a dramatic reduction in cell number in specialized tissues (62). Although cyclin D1−/− fibroblasts were reported to maintain normal growth characteristics when cultured under standard conditions (21), recent evidence suggests that these effects are cell density dependent, since substantial proliferation defects do occur in fibroblasts lacking cyclin D1 when seeded at lower cell density (14).

Implications in oncogenesis.

Finally, the results presented in this study may also have broader implications for understanding how NF-κB participates in oncogenesis. Cyclin D1 levels are deregulated in many human cancers as a result of gene amplification or translocations or of aberrant overexpression (31, 34, 59). Studies with transgenic mice also show that targeted overexpression of cyclin D1 leads to the development of mammary carcinomas (73). In some instances, overexpression of cyclin D1 in transformed cells is regulated by activated ras genes (2, 43), which is consistent with findings that ras transcriptionally regulates this cyclin (1). Interestingly, our laboratory has found that oncogenic ras stimulates the transactivation function of NF-κB, and that NF-κB is required by ras to induce cellular transformation (23). Therefore, NF-κB may be considered a component of oncogene-induced signaling pathways leading to the activation of cyclin D1, potentially contributing to the onset and/or progression of oncogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Konieczny for the troponin-I and 4RTK reporter plasmids, the Weintraub laboratory for the MyoD expression plasmid, R. Benezra for the Id-1 plasmid, M. Caudy for the Hes-1 plasmid, C. Sherr and Y. Xiong for cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 cDNA plasmids, Y. Xiong for antibodies against cyclin D3 and p27, D. Ballard for the IκBα mutant plasmid, D. Phelps for helpful suggestions, members of the Baldwin laboratory for their scientific input, and M. Mayo for critical review of the manuscript. Appreciation is also extended to C. Scheidereit for sharing data prior to publication.

This research was supported by NIH grants CA73756 and CA72771 and by a grant from the Leukemia Society of America to A.S.B. R.G.P. is a recipient of the Ira T. Hirschl award and an award from the Susan G. Komen Breast Foundation. Work conducted at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine was supported by Cancer Center Core NIH grant 5-P30-CA13330-26. D.C.G. was supported by ACS postdoctoral fellowship training grant PF-99-038-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albanese C, Johnson J, Watanabe G, Eklund N, Vu D, Arnold A, Pestell R G. Transforming p21ras mutants and c-Ets-2 activate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinguishable regions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23589–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber N, Sutter T, Miyake M, Kahn S M, Venkatraj V S, Sobrino A, Warburton D, Holt P R, Weinstein I B. Increased expression of cyclin D1 and the Rb tumor suppressor gene in c-K-ras transformed rat enterocytes. Oncogene. 1996;12:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeuerle P A, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin A S., Jr The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin A S, Jr, Azizkhan J C, Jensen D E, Beg A A, Coodly L R. Induction of NF-kappa B DNA-binding activity during the G0-to-G1 transition in mouse fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4943–4951. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bargou R C, Emmerich F, Krappmann D, Bommert K, Mapara M Y, Arnold W, Royer H D, Grinstein E, Greiner A, Scheidereit C, Dorken B. Constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cells. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2961–2969. doi: 10.1172/JCI119849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassuk A G, Anandappa R T, Leiden J M. Physical interactions between Ets and NF-kappaB/NFAT proteins play an important role in their cooperative activation of the human immunodeficiency virus enhancer in T cells. J Virol. 1997;71:3563–3573. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3563-3573.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beg A A, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beg A A, Ruben S M, Scheinman R I, Haskill S, Rosen C A, Baldwin A S., Jr I kappa B interacts with the nuclear localization sequences of the subunits of NF-kappa B: a mechanism for cytoplasmic retention. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1899–1913. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beg A A, Sha W C, Bronson R T, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benezra R, Davis R L, Lockshon D, Turner D L, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brockman J A, Scherer D C, McKinsey T A, Hall S M, Qi X, Lee W Y, Ballard D W. Coupling of a signal response domain in IκBα to multiple pathways for NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2809–2818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown J R, Nigh E, Lee R J, Ye H, Thompson M A, Saudou F, Pestell R G, Greenberg M E. Fos family members induce cell cycle entry by activating cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5609–5619. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bushdid P B, Brantley D M, Yull F E, Blaeuer G L, Hoffman L H, Niswander L, Kerr L D. Inhibition of NF-κB activity results in disruption of the apical ectodermal ridge and aberrant limb morphogenesis. Nature. 1998;392:615–618. doi: 10.1038/33435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheshire J L, Baldwin A S., Jr Synergistic activation of NF-κB by tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon via enhanced IκBα degradation and de novo IκBβ degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6746–6754. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cressman D E, Greenbaum L E, Haber B A, Taub R. Rapid activation of post-hepatectomy factor/nuclear factor kappa B in hepatocytes, a primary response in the regenerating liver. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30429–30435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dejardin E, Bonizzi G, Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Merville M P, Bours V. Highly-expressed p100/p52 (NFKB2) sequesters other NF-kappa B-related proteins in the cytoplasm of human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1995;11:1835–1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiDonato J A, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi T S, Takahashi T, Taguchi O, Azuma T, Obata Y. NF-kappa B RelA-deficient lymphocytes: normal development of T cells and B cells, impaired production of IgA and IgG1 and reduced proliferative responses. J Exp Med. 1997;185:953–961. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2364–2372. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finco T S, Baldwin A S. Mechanistic aspects of NF-kappa B regulation: the emerging role of phosphorylation and proteolysis. Immunity. 1995;3:263–272. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finco T S, Westwick J K, Norris J L, Beg A A, Der C J, Baldwin A S., Jr Oncogenic Ha-Ras-induced signaling activates NF-kappaB transcriptional activity, which is required for cellular transformation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24113–24116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgerald M J, Webber E M, Donovan J R, Fausto N. Rapid DNA binding by nuclear factor kappa B in hepatocytes at the start of liver regeneration. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:417–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franzoso G, Carlson L, Xing L, Poljak L, Shores E W, Brown K D, Leonardi A, Tran T, Boyce B F, Siebenlist U. Requirement for NF-kappaB in osteoclast and B-cell development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3482–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerritsen M E, Williams A J, Neish A S, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grumont R J, Gerondakis S. The subunit composition of NF-kappa B complexes changes during B-cell development. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1321–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grumont R J, Rourke I J, O’Reilly L A, Strasser A, Miyake K, Sha W, Gerondakis S. B lymphocytes differentially use the rel and nuclear factor kB1(NF-kB1) transcription factors to regulate cell cycle progression and apoptosis in quiescent and mitogen-activated cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:663–674. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]