Abstract

Determining compositional trends among individual minerals is key to understanding the thermodynamic conditions under which they formed and altered, and is also essential to maximizing the scientific value of small extraterrestrial samples, including returned samples and meteorites. Here we report the chemical compositions of Fe-sulfides, focusing on the pyrrhotite-group sulfides, which are ubiquitous in chondrites and are sensitive indicators of formation and alteration conditions in the protoplanetary disk and in small Solar System bodies. Our data show that while there are trends with the at.% Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite with thermal and aqueous alteration in some meteorite groups, there is a universal trend between the Fe/S ratio and degree of oxidation. Relatively reducing conditions led to the formation of troilite during: (1) chondrule formation in the protoplanetary disk (i.e., pristine chondrites) and (2) parent body thermal alteration (i.e., LL4 to LL6, CR1, CM, and CY chondrites). Oxidizing and sulfidizing conditions led to the formation of Fe-depleted pyrrhotite with low Fe/S ratios during: (1) aqueous alteration (i.e., CM and CI chondrites), and (2) thermal alteration (i.e., CK and R chondrites). The presence of troilite in highly aqueously altered carbonaceous chondrites (e.g., CY, CR1, and some CM chondrites) indicates they were heated after aqueous alteration. The presence of troilite, Fe-depleted pyrrhotite, or pyrite in a chondrite can provide an estimate of the oxygen and sulfur fugacities at which it was formed or altered. The data reported here can be used to estimate the oxygen fugacity of formation and potentially the aqueous and/or thermal histories of sulfides in extraterrestrial samples, including those returned by the Hayabusa2 mission and due to be returned by the OSIRIS-REx mission in the near future.

Keywords: Sulfide, Pyrrhotite, Troilite, Pyrite, Chondrite, Oxidation, Asteroid sample return

1. INTRODUCTION

In the next few years, the planetary science community will have access to samples of asteroids 162173 Ryugu (returned to Earth on Dec. 6th, 2020) and 101955 Bennu (nominal return Sept. 24th, 2023) to study in laboratories on Earth (e.g., Lauretta et al., 2017; Tsuda et al., 2019). Among the first questions researchers will aim to answer is how the returned material relates to known meteorites. For instance, the first studies of particles returned from asteroid 25143 Itokawa by JAXA’s Hayabusa mission determined that it contains material similar to LL4 to LL6 chondrites, with ~10% matching LL4 and ~90% matching LL5 to LL6 (e.g., Nakamura et al., 2011; Tsuchiyama et al., 2011, 2014; Noguchi et al., 2014). One mineral system that can aid making these comparisons and constrain parent body alteration conditions is the pyrrhotite group sulfides. As some returned particles are monomineralic, including monomineralic sulfide grains (e.g., Nakamura et al., 2011), being able to determine the parent body history of extraterrestrial material from a single mineral system would provide significant insight into the pre- and post-accretionary history of small bodies in the Solar System.

Fe-sulfides are ubiquitous in and important constituents of chondrites (Table 1), and are sensitive indicators of formation and alteration conditions in the protoplanetary disk and small Solar System bodies (e.g., Weisberg et al., 2006; Schrader et al., 2016, 2018; Singerling and Brearley, 2020). Chondritic sulfides can form in multiple different environments including gas–solid/melt reactions in the protoplanetary disk (e.g., Zolensky and Thomas, 1995; Lauretta et al., 1996, 1997, 1998; Schrader et al., 2008; Schrader and Lauretta, 2010; Marrocchi and Libourel, 2013; Piani et al., 2016), as an igneous product of chondrule formation in the protoplanetary disk (e.g., Schrader et al., 2015, 2018; Singerling and Brearley, 2018), and also by secondary processing in the parent asteroid (e.g., Harries and Langenhorst, 2013; Schrader et al., 2016; Singerling and Brearley, 2020). The compositions and textures of sulfides can be used to constrain the oxygen and sulfur fugacities of formation, and the histories of aqueous alteration, thermal metamorphism, shock-impact processing, and cooling of the host rock (e.g., Bennett and McSween, 1996; Raghavan, 2004; Kimura et al., 2011; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013; Schrader et al., 2016, 2018; Schrader and Zega, 2019). Sulfur and oxygen fugacities are dependent on temperature and, under certain conditions, can be correlated with one another (e.g., Whitney, 1984; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013). In addition, the major and minor element compositions of the Fe,Ni sulfide pentlandite, (Fe,Ni)9S8, has been shown to vary among different meteorite groups (Schrader et al., 2016). The most abundant sulfides in known astromaterials are the pyrrhotite group (ideally Fe1−xS where x is typically 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.125, but x can be ≤0.2; i.e., FeS [troilite] to Fe0.8S; e.g., Naldrett, 1989; Haldar, 2017), which can occur with pentlandite and pyrite FeS2 (e.g., Bullock et al., 2005; Tachibana and Huss, 2005; Berger et al., 2011; Kimura et al., 2011; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013; Harries and Zolensky, 2016; Schrader et al., 2016, 2018; Singerling and Brearley, 2018, 2020). Troilite ideally has an at.% Fe/S ratio of 1 but can have Fe/S ratios between 1 and 0.98 (e.g., Lauretta et al., 1996, 1997), while Fe-depleted pyrrhotite has Fe/S ratios between0.98 and 0.8 (e.g., Naldrett, 1989; Haldar, 2017). Low-Ni Fe sulfides are particularly important because they are more susceptible to alteration than high-Ni sulfides in the CM and CR chondrites (Singerling and Brearley, 2020). The compositions of pyrrhotite in carbonaceous chondrites vary with the degree of aqueous alteration experienced; the at.% Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite decreases with increasing degrees of aqueous alteration (i.e., Fe/S of pyrrhotite in CI < CM1 < CM2 [Bullock et al., 2005; Berger et al., 2011; Harries and Zolensky, 2016; Harries, 2018; Kimura et al., 2020]). Troilite (FeS, ideally Fe/S = 1) was observed in aqueously altered and heated CM and CY chondrites (e.g., Nakamura, 2005; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013; Harries, 2018; Suttle et al., 2021). This troilite was proposed to have formed by S loss during heating and decomposition of pyrrhotite into troilite and Ni-poor metal (Harries, 2018). In contrast, it has also been proposed that troilite in heated carbonaceous chondrites was secondary and the result of decomposition of S-bearing hydrous phases (i.e., tochilinite) during heating (Nakamura, 2005; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013). However, previous observations of pyrrhotite and their implied formation processes are based on a limited set of samples. The full range of Fe/S ratios in pyrrhotite from different meteorite groups are not well known, and if and how the Fe/S ratio relates to protoplanetary-disk and parent-body processes is not yet fully understood.

Table 1.

Abundance of sulfides in chondrite groups.

| Meteorite Group | Volume % | Referencesa |

|---|---|---|

| CI | 2.2–7.0 | 1,2 |

| CY | 12–28 | 3,4 |

| CM | 0.6–5.4 | 5 |

| CO3 | 2–3 | 6 |

| CRb | 2.3–9.3 | 5,7 |

| CV3 | 1.3–9.9 | 2,8 |

| CK | ~1 | 9 |

| H | 4.1–7.0 | 10 |

| L | 1.5–10.3 | 2,10 |

| LL | 4.2–8.6 | 10 |

| R | ~6 | 11 |

(1) King et al. (2015); (2) Donaldson Hanna et al. (2019); (3) King et al. (2019); (4) Suttle et al. (2021); (5) Howard et al. (2015); (6) Alexander et al. (2018); (7) Schrader et al. (2014); (8) Howard et al. (2010); (9) Geiger and Bischoff (1995); (10) Dunn et al. (2010); (11) Bischoff et al. (2011).

Weathered hot desert samples have abundances down to 0.2 vol.% due to sulfide weathering [7,8].

In order to fill this knowledge gap, here we discuss the Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite in multiple chondrite groups with a variety of aqueous and thermal histories. We evaluate its usefulness as an indicator of formation and alteration conditions and its application to the analysis of returned samples. Minimally altered samples and those that have experienced varied types and degrees of secondary processing are included because: (1) asteroid Bennu is most like CM or CI chondrites (e.g., Hamilton et al., 2019); (2) asteroid Ryugu is most like heated CI, CM (e.g., Kitazato et al., 2019, 2021), or CY chondrites (King et al., 2019); and (3) both asteroids include impact-delivered exogenous material (e.g., DellaGiustina et al., 2020; Tatsumi et al., 2021).

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

2.1. Samples

We studied the sulfide compositions of 58 different chondrites including samples of CI (Alais, Ivuna, and Orgueil), a C1-ungrouped (Miller Range [MIL] 090292), CY (Belgica [B]-7904, Y-82162, Y-86789, and Y-980115), CM1/2 (Allan Hills [ALH] 83100 and Kolang, two lithologies), CM2 (Aguas Zarcas, Mighei, and Queen Alexandra Range [QUE] 97990), stage I heated CM2 (Asuka [A]-881458), stage II heated CM2 (Yamato [Y]-793321), CM-like (Sutter’s Mill), CO3.00 (Dominion Range [DOM] 08006), CR1 (Grosvenor Mountains [GRO] 95577), CR-an (Al Rais), CR2 (Elephant Moraine [EET] 87770, EET 92048, EET 96259, Gao-Guenie (b), Graves Nunatak [GRA] 95229, LaPaz Ice Field [LAP] 02342, LAP 04720, Meteorite Hills [MET] 00426, MIL 090657, Northwest Africa [NWA] 801, Pecora Escarpment [PCA] 91082, QUE 99177, Shişr 033, and Y-793495), shock-heated CR2 (GRA 06100 and GRO 03116), CV3OxA (Allende), CV3OxB (Bali), and CV3Red (Vigarano), CK4 (ALH 85002 and Karoonda), CK5 (Larkman Nunatak [LAR] 06868), CK6 (Lewis Cliff [LEW] 87009), H3.10 (NWA 3358), L3.05 (QUE 97008), L(LL) 3.05 (MET 00452), LL3 (Semarkona and Vicência), LL4 (Hamlet and Soko-Banja), LL5 (Chelyabinsk and Siena), LL6 (Appley Bridge and Saint-Séverin), R3 (MET 01149), R3.6 (LAP 031275), R5 (LAP 03639), and R6 (LAP 04840 and MIL 11207) chondrites. CM chondrite heating stages for A-881458 and Y-793321 are from Nakamura (2005). Some Fe/S ratios were determined from previously measured sulfides; R and CK (Schrader et al., 2016), LL (Schrader et al., 2016; Schrader and Zega, 2019), CR2 (Schrader et al., 2015, 2018; Davidson et al., 2019a; this study), CM (Schrader et al., 2016; this study), and CO3.00 (Davidson et al., 2019b) chondrites. Meteorite group names are given in Tables 2a and 2b. Specific sample split and institution numbers are given in Tables 3 and 4, and EA-1.

Table 2a.

Major and minor element compositional averages and ranges of low-Ni pyrrhotite (wt.%) in carbonaceous chondrites.

| Groupa | Meteoriteb | Fe | S | Si | P | Ti | Mn | Ca | Ni | Co | Cr | Mg | Al | Cu | Total | # Analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Alais | avg ± σ | 58.9 ± 0.4 | 39.7 ± 0.4 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | 99.44 ± 0.59 | 22 |

| min–max | 58.2–59.5 | 38.8–40.6 | bdl–0.08 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.04 | bdl–0.09 | 0.49–0.92 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.06 | bdl–0.04 | bdl | ||||

| CI | Ivuna | avg ± σ | 59.4 ± 0.3 | 39.2 ± 0.7 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | bdl | nd | bdl | nd | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | nd | 0.01 ± 0.03 | nd | bdl | 99.59 ± 0.85 | 22 |

| min–max | 58.6–59.9 | 38.2–41.1 | bdl–0.11 | bdl | nd | bdl | nd | 0.83–0.98 | bdl–0.05 | nd | bdl–0.12 | nd | bdl | ||||

| CI | Orgueil | avg ± σ | 58.3 ± 0.4 | 39.3 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.91 ± 0.05 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | nd | 98.58 ± 0.46 | 8 |

| min–max | 57.8–58.9 | 38.9–39.6 | 0.02–0.04 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.83–0.98 | bdl | bdl–0.04 | bdl | bdl | nd | ||||

| CM1/2 | ALH 83100 | avg ± σ | 60.8 ± 0.7 | 38.3 ± 0.6 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.26 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | 99.81 ± 0.43 | 10 |

| min–max | 60.0–62.2 | 37.3–39.1 | bdl–0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.05 | bdl–0.05 | 0.36–0.97 | bdl–0.14 | bdl–0.04 | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CM1/2 | Kolang (avg) | avg ± σ | 60.3 ± 0.4 | 38.9 ± 0.1 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.70 ± 0.12 | bdl | 0.03 ± 0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.93 ± 0.33 | 20 |

| min–max | 59.4–61.1 | 38.7–39.1 | 0.03–0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.46–0.88 | bdl | bdl–0.20 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CM2 (stage I)c | A-881458 | avg ± σ | 60.3 ± 0.4 | 38.7 ± 0.3 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | 0.03 ± 0.06 | nd | 0.64 ± 0.16 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.83 ± 0.37 | 14 |

| min–max | 59.2–60.9 | 38.1–39.1 | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.21 | nd | 0.39–0.93 | bdl–0.13 | bdl–0.27 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CM2 | Aguas Zarcas (avg) | avg ± σ | 60.5 ± 0.4 | 38.1 ± 0.5 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.62 ± 0.18 | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.28 ± 0.79 | 7 |

| min–max | 59.9–61.0 | 37.5–38.7 | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.45–0.95 | bdl–0.13 | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CM2 | Mighei | avg ± σ | 61.3 ± 0.9 | 37.7 ± 0.8 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.47 ± 0.16 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 99.57 ± 0.63 | 7 |

| min–max | 59.9–62.5 | 36.2–38.7 | bdl–0.10 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.04–0.04 | 0.26–0.69 | bdl | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.09 | ||||

| CM2 | QUE 97990 | avg ± σ | 62.0 ± 0.6 | 36.5 ± 0.4 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.03 | nd | 0.54 ± 0.15 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.24 ± 0.36 | 11 |

| min–max | 60.9–62.7 | 36.1–37.3 | bdl–0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.09 | nd | 0.33–0.77 | bdl–0.16 | bdl–0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CM2 (stage II)c | Y-793321 | avg ± σ | 62.7 ± 0.5 | 37.4 ± 0.4 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.16 ± 0.18 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | bdl | bdl | nd | 100.34 ± 0.51 | 33 |

| min–max | 61.6–63.4 | 36.7–38.6 | bdl–0.16 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | bdl–0.88 | bdl–0.16 | bdl–0.25 | bdl | bdl | nd | ||||

| CM-like | Sutter’s Mill | avg ± σ | 61.8 ± 0.8 | 38.3 ± 0.6 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.64 ± 0.15 | bdl | 0.03 ± 0.05 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 100.76 ± 0.71 | 11 |

| min–max | 61.0–63.7 | 37.2–39.1 | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.44–0.99 | bdl | bdl–0.15 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.10 | ||||

| CY | B-7904 | avg ± σ | 62.6 ± 0.4 | 36.5 ± 0.1 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | 0.17 ± 0.20 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | bdl | nd | 99.35 ± 0.29 | 22 |

| min–max | 61.6–63.1 | 36.1–36.8 | bdl–0.13 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.04 | nd | bdl–0.87 | bdl | bdl–0.07 | bdl–0.14 | bdl | nd | ||||

| CY | Y-82162 | avg ± σ | 63.0 ± 0.5 | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 0.07 ± 0.13 | bdl | nd | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | 0.19 ± 0.20 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | 0.07 ± 0.12 | nd | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 100.07 ± 0.57 | 64 |

| min–max | 60.5–63.8 | 35.7–38.0 | bdl–0.71 | bdl | nd | bdl–0.06 | nd | bdl–0.89 | bdl–0.03 | nd | bdl–0.67 | nd | bdl–0.08 | ||||

| CY | Y-86789 | avg ± σ | 63.4 ± 0.2 | 37.0 ± 0.2 | 0.00 ± 0.02 | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | nd | 100.39 ± 0.32 | 27 |

| min–max | 62.9–63.8 | 36.8–37.3 | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.04 | nd | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | nd | ||||

| CY | Y-980115 | avg ± σ | 62.3 ± 0.5 | 36.8 ± 0.5 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | bdl | nd | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | 0.29 ± 0.24 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | 0.06 ± 0.09 | nd | bdl | 99.44 ± 0.66 | 100 |

| min–max | 60.3–63.4 | 35.6–37.9 | bdl–0.4 | bdl | nd | bdl–0.09 | nd | 0.04–0.98 | bdl–0.04 | nd | bdl–0.49 | nd | bdl | ||||

| C1-ung | MIL 090292 | avg ± σ | 61.4 ± 0.6 | 38.3 ± 0.7 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.21 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | 0.04 ± 0.07 | 100.90 ± 1.00 | 4 |

| min–max | 60.6–61.9 | 37.7–39.0 | 0.02–0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.19–0.23 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.05 | bdl | bdl–0.14 | ||||

| CR1 | GRO 95577 | avg ± σ | 62.6 ± 0.3 | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.68 ± 0.37 | 3 |

| min–max | 62.3–62.9 | 36.4–37.2 | bdl–0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.03 | 0.17–0.44 | bdl | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CR-an | Al Rais | avg ± σ | 60.0 ± 0.6 | 37.7 ± 0.1 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.60 ± 0.08 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 98.44 ± 0.53 | 3 |

| min–max | 59.4–60.5 | 37.6–37.8 | bdl–0.10 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.52–0.67 | bdl | bdl–0.04 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CR2 | 14 samplesb | avg ± σ | 62.3 ± 0.6 | 36.4 ± 0.3 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.29 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | 0.07 ± 0.09 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.08 | 99.40 ± 0.45 | 287 |

| min–max | 59.7–63.9 | 35.5–38.1 | bdl–0.15 | bdl–0.07 | bdl–0.04 | bdl–0.45 | bdl–0.11 | bdl–0.98 | bdl–0.25 | bdl–0.70 | bdl–0.12 | bdl–0.11 | bdl–0.79 | ||||

| CR2 (shock-heated) | GRA 06100 and GRO 03116 | avg ± σ | 62.5 ± 0.6 | 36.7 ± 0.5 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.22 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | 99.37 ± 0.45 | 52 |

| min–max | 61.0–63.8 | 35.8–38.0 | bdl–0.13 | bdl–0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.11 | bdl–0.94 | bdl | bdl–0.34 | bdl–0.06 | bdl–0.04 | bdl | ||||

| CO3 | DOM 08006 | avg ± σ | 63.2 ± 0.3 | 36.5 ± 0.2 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.09 ± 0.13 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | bdl | nd | nd | bdl | 99.90 ± 0.37 | 9 |

| min–max | 62.3–63.5 | 36.2–36.9 | bdl–0.04 | nd | nd | nd | nd | bdl–0.41 | 0.07–0.10 | bdl | nd | nd | bdl | ||||

| CV3OxA | Allende | avg ± σ | 63.0 ± 0.2 | 37.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.06 ± 0.15 | bdl | 0.05 ± 0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.09 ± 0.18 | 12 |

| min–max | 62.6–63.3 | 36.7–37.2 | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.04 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.50 | bdl | bdl–0.17 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CV3OxB | Bali | avg ± σ | 63.2 ± 0.3 | 36.8 ± 0.1 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.20 ± 0.35 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.18 ± 0.11 | 5 |

| min–max | 62.8–63.4 | 36.7–36.9 | 0.02–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.81 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CV3Red | Vigarano | avg ± σ | 63.4 ± 0.6 | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.11 | bdl | bdl | 0.06 ± 0.17 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.12 ± 0.72 | 11 |

| min–max | 61.8–63.9 | 35.9–37.0 | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.36 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.55 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| CK4 | Karoonda | avg ± σ | 57.3 | 40.9 | bdl | bdl | nd | nd | nd | 0.82 | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.03 | bdl | 99.04 | 1 |

| min–max | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

avg = average, one standard deviation = s, min = minimum, max = maximum, nd = not determined, bdl = below detection limit. Detection limits given in EA-1. ALH 85300 (CK4), LAR 06868 (CK5), and LEW 87009 (CK6) do not contain pyrrhotite.

Chondrite Group Abbreviations: CI = Ivuna-like carbonaceous; CM = Mighei-like carbonaceous; CY = Yamato-like carbonaceous; CR = Renazzo-like carbonaceous; CO = Ornans-like carbonaceous; CV = Vigarano-like carbonaceous; and CK = Karoonda-like carbonaceous.

See Section 2.1. for individual sample split numbers and CR chondrites studied.

CM2 heating stages fromNakamura (2005)

Table 2b.

Major and minor element compositional averages and ranges of low-Ni pyrrhotite (wt.%) in ordinary and rumuruti chondrites.

| Groupa | Meteoriteb | Fe | S | Si | P | Ti | Mn | Ca | Ni | Co | Cr | Mg | Al | Cu | Total | # Analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3.10 | NWA 3358 | avg ± σ | 63.1 ± 1.0 | 36.6 ± 0.5 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | 0.06 ± 0.17 | bdl | 0.04 ± 0.10 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.77 ± 0.58 | 19 |

| min–max | 59.5–63.8 | 36.1–38.0 | bdl–0.11 | bdl | bdl | bdl | nd | bdl–0.70 | bdl | bdl–0.42 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| L3.05 | QUE 97008 | avg ± σ | 62.9 ± 0.4 | 36.7 ± 0.2 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | bdl | 0.06 ± 0.06 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.77 ± 0.48 | 19 |

| min–max | 62.1–63.8 | 36.3–37.0 | bdl–0.10 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.10 | bdl–0.37 | bdl | bdl–0.21 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| L(LL)3.05 | MET 00452 | avg ± σ | 63.6 ± 0.1 | 36.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.05 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.37 ± 0.15 | 13 |

| min–max | 63.4–63.9 | 36.5–36.9 | bdl–0.07 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.16 | bdl | bdl–0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| LL3 | Semarkona | avg ± σ | 63.1 ± 0.4 | 36.8 ± 0.2 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.20 | bdl | 0.04 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.03 ± 0.40 | 33 |

| min–max | 62.4–63.8 | 36.4–37.2 | bdl–0.13 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.06 | bdl–0.90 | bdl | bdl–0.08 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| LL3 | Vicência | avg ± σ | 63.2 ± 0.3 | 36.6 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.09 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.01 ± 0.04 | bdl | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 100.07 ± 0.42 | 23 |

| min–max | 62.1–63.9 | 36.1–37.1 | bdl–0.24 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.37 | bdl | bdl–0.25 | bdl–0.19 | bdl | bdl–0.32 | ||||

| LL4 | Hamlet | avg ± σ | 63.4 ± 0.2 | 36.8 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.05 ± 0.09 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.37 ± 0.29 | 19 |

| min–max | 63.0–63.9 | 36.6–37.2 | bdl–0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.27 | bdl | bdl–0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| LL4 | Soko-Banja | avg ± σ | 63.4 ± 0.5 | 37.2 ± 0.2 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 100.64 ± 0.68 | 38 |

| min–max | 62.2–64.3 | 36.7–37.6 | bdl–0.07 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.05 | bdl | bdl–0.09 | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| LL5 | Chelyabinsk | avg ± σ | 63.1 ± 0.5 | 36.8 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.13 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.05 ± 0.19 | 100.14 ± 0.64 | 22 |

| min–max | 62.2–64.3 | 36.5–37.1 | bdl–0.08 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.03 | bdl–0.58 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.88 | ||||

| LL5 | Siena | avg ± σ | 63.2 ± 0.6 | 36.5 ± 0.3 | 0.05 ± 0.10 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | bdl | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.04 | bdl | bdl | 99.88 ± 0.63 | 9 |

| min–max | 62.1–63.8 | 35.8–37.0 | bdl–0.31 | bdl–0.07 | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.11 | bdl–0.16 | bdl–0.14 | bdl | bdl–0.11 | bdl | bdl | ||||

| LL6 | Appley Bridge | avg ± σ | 63.4 ± 0.3 | 36.6 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.07 ± 0.11 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.07 ± 0.19 | 100.17 ± 0.25 | 12 |

| min–max | 62.8–63.9 | 36.4–36.7 | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.29 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.66 | ||||

| LL6 | Saint-Séverin | avg ± σ | 63.1 ± 0.8 | 36.8 ± 0.4 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.05 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 99.88 ± 1.14 | 16 |

| min–max | 61.8–64.0 | 36.1–37.8 | bdl–0.03 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl–0.15 | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | ||||

| R3 | MET 01149 | avg ± σ | 62.1 ± 0.8 | 38.3 ± 0.6 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.03 | nd | nd | nd | 0.18 ± 0.07 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.06 | nd | 0.01 ± 0.04 | bdl | 100.61 ± 0.78 | 31 |

| min–max | 61.2–64.2 | 36.9–39.3 | bdl | bdl–0.09 | nd | nd | nd | 0.05–0.36 | bdl | bdl–0.27 | nd | bdl–0.22 | bdl | ||||

| R3.6 | LAP 031275 | avg ± σ | 61.6 ± 0.7 | 38.2 ± 0.6 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.06 | nd | nd | nd | 0.12 ± 0.15 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.03 | nd | bdl | bdl | 99.90 ± 0.45 | 39 |

| min–max | 60.3–63.1 | 37.1–39.2 | bdl | bdl–0.31 | nd | nd | nd | bdl–0.71 | bdl | bdl–0.10 | nd | bdl | bdl | ||||

| R5 | LAP 03639 | avg ± σ | 61.1 ± 0.6 | 38.1 ± 0.6 | bdl | 0.00 ± 0.01 | nd | nd | nd | 0.08 ± 0.06 | bdl | 0.01 ± 0.04 | nd | bdl | bdl | 99.25 ± 0.59 | 40 |

| min–max | 60.0–62.6 | 36.9–39.3 | bdl | bdl–0.07 | nd | nd | nd | bdl–0.25 | bdl | bdl–0.22 | nd | bdl | bdl | ||||

| R6 | MIL 11207 | avg ± σ | 59.4 ± 0.7 | 39.0 ± 0.2 | bdl | bdl | nd | nd | nd | 0.92 ± 0.04 | bdl | 0.02 ± 0.03 | nd | bdl | bdl | 99.35 ± 0.85 | 4 |

| min–max | 58.8–60.5 | 38.8–39.2 | bdl | bdl | nd | nd | nd | 0.89–0.97 | bdl | bdl–0.06 | nd | bdl | bdl |

avg = average, one standard deviation = s, min = minimum, max = maximum, nd = not determined, bdl = below detection limit. Detection limits given in EA-1. LAP 04840 (R6) did not contain pyrrhotite large enough for a clean analysis that did not include beam overlap with pentlandite lamellae.

Chondrite group abbreviations: H, L, and LL = ordinary; and R = rumuruti-like.

See Section 2.1 for individual sample split numbers.

Table 3.

Average at.% Fe/S ratios of low-Ni pyrrhotite and estimated metamorphic temperatures of chondrites.

| Group | Meteorite | Sample Number | avg. Fe/S | 1 σ | 1 SE | min Fe/S | max Fe/S | # low-Ni Po | # high-Ni Po | # Pyrite | Sulfide Reference | Estimated Metamorphic Temperatureb | Temperature Method | Temperature Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Orgueil | USNM6765-2 | 0.852 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.844 | 0.863 | 8 | 1 | a | 50–150 °C | matrix mineralogy | h | |

| CI | Alais | USNM6695-5 | 0.853 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.837 | 0.870 | 22 | 1 | a | 50–150 °C | matrix mineralogy | h | |

| CI | Ivuna | P12627 | 0.869 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.832 | 0.889 | 22 | 32 | a | 50–150 °C | matrix mineralogy | h | |

| C1-ung | MIL 090292 | ,4 | 0.920 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.909 | 0.943 | 4 | 0 | a | <210 °C | cubanite | a (based on [i and j]) | |

| CY | Y-980115 | ,123-1 | 0.973 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.940 | 1.003 | 100 | 38 | a | 500–750 °C | dehydration | k, l | |

| CY | Y-86789 | ,81-2 | 0.983 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.973 | 0.993 | 27 | 0 | a | >750 °C | dehydration | l, m, n, o | |

| CY | Y-82162 | ,45-1 | 0.985 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.951 | 1.005 | 64 | 19 | a | 500–750 °C | dehydration | k, l | |

| CY | B-7904 | ,04A-1 | 0.986 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.972 | 0.995 | 22 | 1 | a | >750 °C | dehydration | l, m, n, o | |

| CM1/2 | ALH 83100 | ,189 | 0.911 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.882 | 0.945 | 10 | 6 | a | <220 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| CM1/2 | Kolang avg. | See Table 4 | 0.890 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.873 | 0.900 | 20 | 7 | a | – | – | – | |

| CM2 heating stage Ia | A-881458 | ,51-13 | 0.895 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.878 | 0.915 | 14 | 2 | a | <300 °C | dehydration | k | |

| CM2 | Aguas Zarcas avg. | See Table 4 | 0.912 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.897 | 0.928 | 7 | 11 | a | – | – | – | |

| CM-like | Sutter’s Mill | SM8 | 0.928 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.896 | 0.984 | 11 | 4 | a, b | 150–500 °C | various | q | |

| CM2 | Mighei | USNM3483-3 | 0.933 | 0.031 | 0.012 | 0.898 | 0.990 | 7 | 4 | a, b | <220 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| CM2 heating stage IIa | Y-793321 | ,60-4 | 0.963 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.919 | 0.985 | 33 | 1 | a | 300–500 °C | dehydration | k | |

| CM2 | QUE 97990 | ,53 | 0.975 | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.940 | 0.989 | 11 | 13 | a | <100 °C | pristine metal | r | |

| CO3.00 | DOM 08006 | ,16 | 0.994 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.982 | 1.003 | 9 | 2 | c | <100 °C | pristine metal | c | |

| CR1 | GRO 95577 | ,4 | 0.980 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.962 | 0.992 | 3 | 3 | a | 55 to <220 °C | graphite-ordering | j, p | |

| CR-an | Al Rais | USNM1794-8 | 0.914 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.901 | 0.920 | 3 | 3 | a | 60 to <220 °C | graphite-ordering | j, p | |

| CR2 | 14 sample avg | See Table 4 | 0.981 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 0.898 | 1.004 | 287 | 186 | a, d, e, f | 55 to <240 °C | graphite-ordering | j, p | |

| CR2-shocked | 2 sample avg. | See Table 4 | 0.979 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.923 | 1.004 | 52 | 7 | a, d | >610 °C | pentlandite loss | d, s | |

| CV3OxA | Allende | ASU818 | 0.978 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.972 | 0.986 | 12 | 0 | a | <590 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| CV3OxB | Bali | USNM4839,1 | 0.987 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.982 | 0.989 | 5 | 1 | a | – | – | – | |

| CV3Red | Vigarano | ASU590_C_1 | 0.992 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.987 | 1.000 | 11 | 0 | a | <370 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| CK4 | ALH 85002 | ,87 | all pyrite | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 20 | b | 647–867 °C | Fe-Mg ol diffusion | t |

| CK4 | Karoonda | USNM2428-3 | 0.806 | – | – | 0.806 | 0.806 | 1 | 0 | 12 | b | 647–867 °C | Fe-Mg ol diffusion | t |

| CK5 | LAR 06868 | ,2 | all pyrite | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 8 | b | 647–867 °C | Fe-Mg ol diffusion | t |

| CK6 | LEW 87009 | ,2 | all pyrite | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 13 | b | 740 ± 38 °C | two-pyx | b |

| H3.10 | NWA 3358 | PL18038 | 0.990 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.900 | 1.008 | 19 | 0 | a | ~250–350 °C | similar 3.1 temps | u | |

| L3.05 | QUE 97008 | ,63 | 0.983 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.970 | 0.994 | 19 | 1 | a | <250 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| L(LL)3.05 | MET 00452 | ,29 | 0.994 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.990 | 1.002 | 13 | 0 | a | 203 ± 70 °C | organic | v | |

| LL3 | Semarkona and Vicência | USNM1805-17 and ASU1996 | 0.987 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.970 | 0.999 | 56 | 9 | g | <220 °C | graphite-ordering | p | |

| LL4 | Soko-Banja and Hamlet | USNM3078-1 and ASU1194_C_2 | 0.982 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.970 | 0.995 | 57 | 3 | g | >600 °C | Fe-Mg ol diffusion | w | |

| LL5 | Siena and Chelyabinsk | USNM3070-3 and ASU1801_22_C1 | 0.986 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.971 | 1.000 | 31 | 0 | g | 867 ± 28 °C | two-pyx | b | |

| LL6 | Saint-Séverin and Appley Bridge | USNM2608-3 and USNM614-3 | 0.990 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.971 | 1.000 | 28 | 17 | g | 899 ± 70 °C | two-pyx | b | |

| R3 | MET 01149 | ,27 | 0.933 | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.902 | 0.995 | 31 | 10 | b | – | – | – | |

| R3.6 | LAP 031275 | ,2 | 0.927 | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.885 | 0.975 | 39 | 1 | b | – | – | – | |

| R5 | LAP 03639 | ,2 | 0.921 | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.880 | 0.963 | 40 | 4 | b | 853 ± 62 °C | two-pyx | b | |

| R6 | LAP 04840 | ,4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 48 | b | 670 ± 60 °C | amph-plag | x | |

| R6 | MIL 11207 | ,2 | 0.873 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.867 | 0.886 | 4 | 40 | b | ≥950 °C | Fe-Ni-S veins | b |

Where Po = pyrrhotite; two-pyx = two-pyroxene equilibration temperature; Fe-Mg ol diffusion = Fe-Mg diffusion in olivine; amph-plag = amphibole-plagioclase thermometry; temps = temperatures

(a) = this study, (b) = Schrader et al. (2016), (c) = Davidson et al. (2019b), (d) = Schrader et al. (2015), (e) = Schrader et al. (2018), (f) = Davidson et al. (2019a), (g) = Schrader and Zega (2019), (h) = Zolensky et al. (1993), (i) = Berger et al. (2015), (j) = Jilly-Rehak et al. (2018), (k) = Nakamura (2005), (l) = King et al. (2019), (m) = Ikeda (1992), (n) = Matsuoka et al. (1996), (o) = Tonui et al. (2014), (p) = Busemann et al. (2007), (q) = Jenniskens et al. (2012), (r) = Kimura et al. (2008), (s) = Abreu and Bullock (2013), (t) = Chaumard and Devouard (2016), (u) = Ebert et al. (2020), (v) = Cody et al. (2008), (w) = Kessel et al. (2007), and (x) = McCanta et al. (2008).

CM2 heating stages from Nakamura (2005).

Estimated metamorphic temperatures may have only been briefly reached. Upper limit estimates may not have been reached and actual temperature may have been much lower.

Table 4.

Average at.% Fe/S ratios of low-Ni pyrrhotite in multiple pieces of CM chondrites and in individual CR chondrites.

| Group | Meteorite | Sample Number | avg. Fe/S | 1 σ | 1 SE | min Fe/S | max Fe/S | # Analyses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM chondrites with multiple sections analyzed | |||||||||

| CM1/2 | Kolang - CM1 clast | ASU2147_C3c | 0.890 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.873 | 0.899 | 17 | a |

| CM1/2 | Kolang - host lithology | ASU2147_C1 | 0.893 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.889 | 0.900 | 3 | a |

| CM2 | Aguas Zarcas | ASU2121_C2 | 0.908 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.897 | 0.916 | 4 | a |

| CM2 | Aguas Zarcas | ASU2121_C6 | 0.919 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.911 | 0.928 | 3 | a |

| CM2 | Aguas Zarcas | ASU2121_C7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | a |

| CR chondrites | |||||||||

| CR-an | Al Rais | USNM1794-8 | 0.914 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.901 | 0.920 | 3 | a |

| CR2 | PCA 91082 | ,15 | 0.970 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.956 | 0.988 | 18 | b |

| CR2 | Shisr 033 | UA2159,1 | 0.971 | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.898 | 0.986 | 26 | b |

| CR2 | EET 92048 | ,7 | 0.975 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.972 | 0.978 | 2 | c |

| CR2 | LAP 02342 | ,14 | 0.977 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.970 | 0.989 | 7 | b |

| CR2 | GRA 95229 | ,22 | 0.978 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.964 | 0.988 | 28 | b |

| CR2 | QUE 99177 | ,6 | 0.979 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.965 | 0.991 | 15 | a,b |

| CR2 | LAP 04720 | ,8 | 0.982 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.962 | 0.994 | 17 | b |

| CR2 | EET 87770 | ,31 | 0.982 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.962 | 0.999 | 45 | a,b |

| CR2 | NWA 801 | UA2300,1 | 0.983 | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.920 | 1.002 | 54 | b |

| CR2 | MET 00426 | ,33 | 0.983 | – | – | 0.983 | 0.983 | 1 | b |

| CR2 | Gao-Guenie (b) | UA2301,1 | 0.984 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.944 | 1.000 | 41 | b |

| CR2 | Y-793495 | ,72-2 | 0.985 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.976 | 1.000 | 14 | b |

| CR2 | EET 96259 | ,12 | 0.990 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.965 | 1.002 | 13 | b |

| CR2 | MIL 090657 | ,6 | 0.994 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.984 | 1.004 | 6 | d |

| CR2 chondrites, shock heated | |||||||||

| CR2 | GRA 06100 | ,26 | 0.972 | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.923 | 0.993 | 37 | a,b |

| CR2 | GRO 03116 | ,15 | 0.995 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.982 | 1.004 | 15 | b |

| CR1 chondrite, heated | |||||||||

| CR1 | GRO 95577 | ,4 | 0.980 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.962 | 0.992 | 3 | a |

Aguas Zarcas ASU2121_C7 has two high-Ni pyrrhotite analyses, but no low-Ni pyrrhotite analyses (EA-1).

(a) This study, (b) Schrader et al. (2015), (c) Schrader et al. (2018), and (d) Davidson et al. (2019a).

2.2. Petrography and chemical analyses

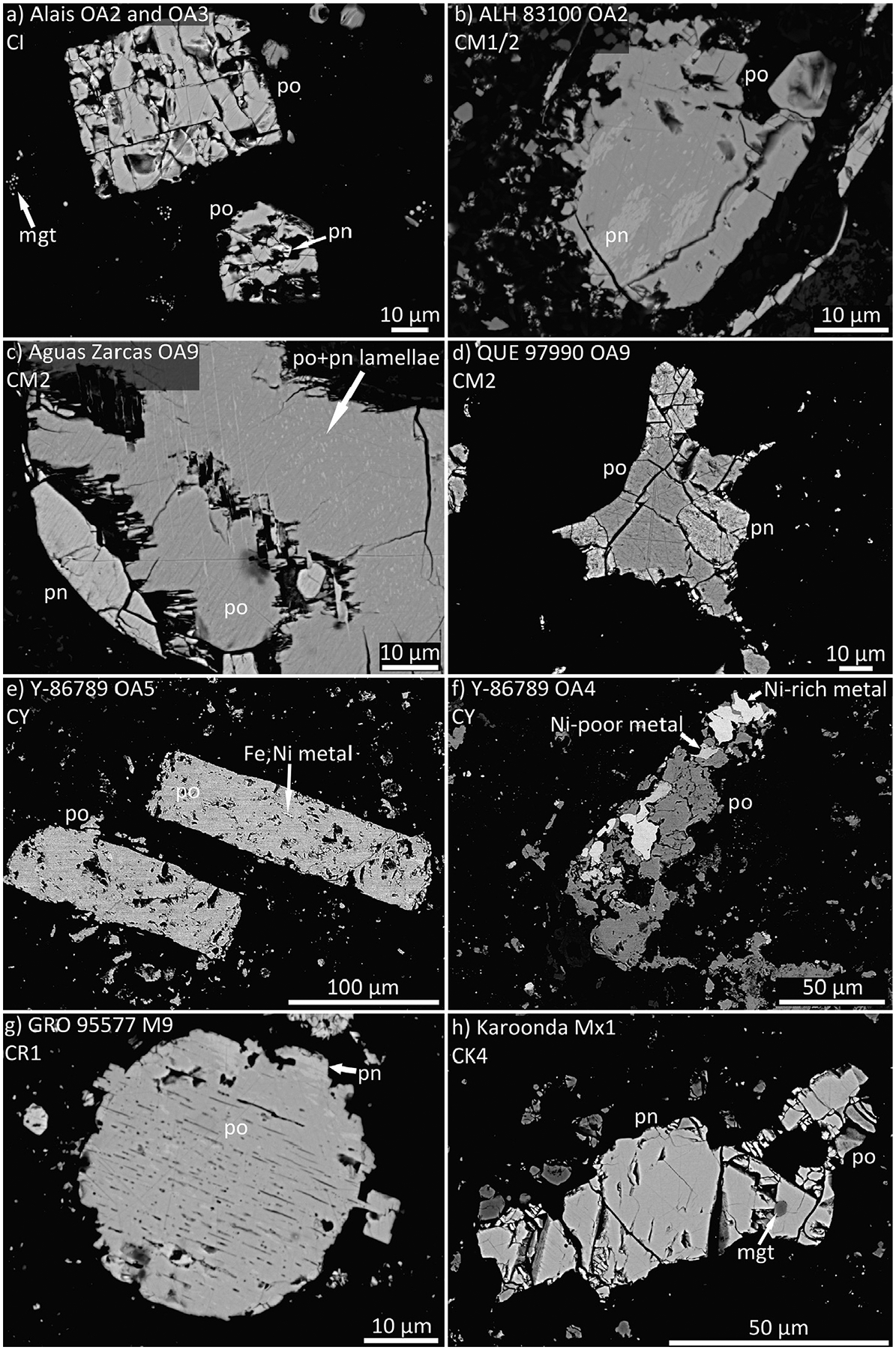

Thin sections were initially characterized using an optical microscope to identify sulfides. We acquired X-ray element maps, high-resolution images, and quantitative chemical compositions with the JEOL-8530F Hyperprobe electron microprobe analyzer (EPMA) at Arizona State University, and the Cameca SX-100 EPMAs at the University of Arizona (UA) and at the Natural History Museum (NHM), London (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Backscattered electron (BSE) images of sulfide grains in the (a) CI Alais, (b), CM1/2 ALH 83100, (c) CM2 Aguas Zarcas, (d) CM2 QUE 97990, (e and f) CY Y-86789, (g) CR1 GRO 95577, and (h) Karoonda CK4. Images of LL, R, CK, and R chondrites can be seen in Schrader et al. (2016) and Schrader and Zega (2019). mgt = magnetite, po = pyrrhotite, pn = pentlandite, Ni-poor metal = Ni < 10 wt.%, and Ni-rich metal = Ni > 10 wt.%.

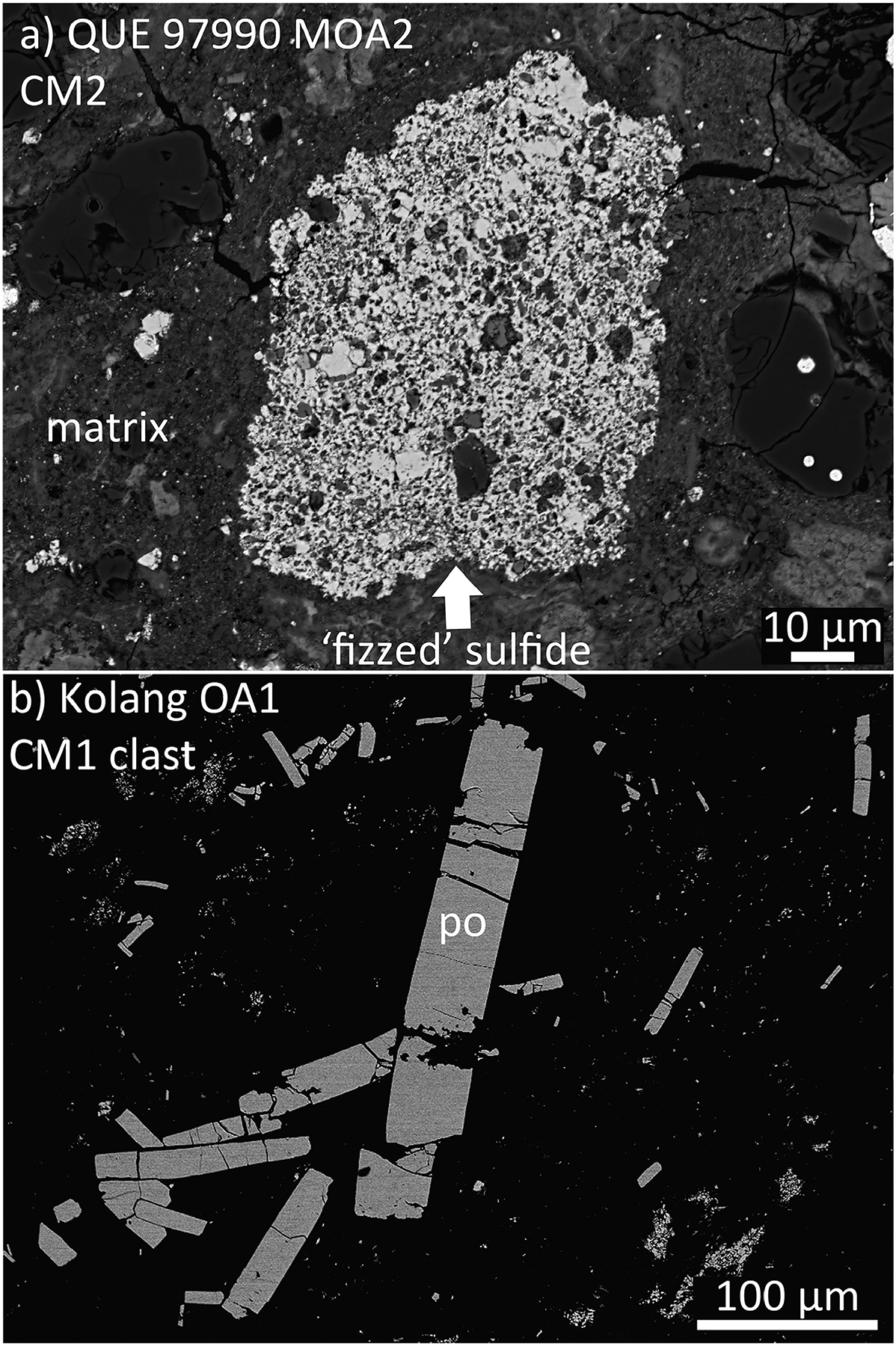

Fig. 2.

BSE images of uncommon sulfide morphologies. (a) ‘Fizzed’ sulfide grain in the matrix of the CM2 QUE 97990,53 and (b) lath shaped sulfides in a CM1 clast from the CM1/2 Kolang (sample ASU2147_C3c). po = pyrrhotite.

The major and minor element compositions of sulfides were determined with the EPMAs at UA and NHM (Tables 2a, 2b and Electronic Annex [EA]-1). In addition to sulfides, some Fe,Ni metal was analyzed in Y-86789 and NWA 3358 to investigate the relationship between Ni and Co. Polished and carbon-coated thin sections were analyzed with a focused beam as individual points, with operating conditions of 15 kV and 20 nA, and a ZAF correction method (a Phi-Rho-Z correction technique); peak and background counting times varied per element to optimize detection limits. Only sulfide and metal analyses with totals between 97.5 and 102 wt.% were retained. EPMA analyses, standards, and detection limits are included in EA-1. The estimated alteration temperatures of meteorites in this study and the techniques to determine those temperatures are listed in Table 3.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Petrography

The sulfides in most samples are rounded, subhedral, or irregular in shape and are present in chondrules and the matrix (Figs. 1 and 2). Sulfides in chondrules within minimally altered chondrites (e.g., CR2) are often rounded or irregular (these crystallized around pre-existing silicate grains) in shape, as primary sulfides were immiscible melts during chondrule cooling (e.g., Schrader et al., 2015). Notable differences to these typical shapes are euhedral grains of pyrrhotite in CI chondrites (e.g., Fig. 1a), rare fizzed-sulfide grains in the CM2 QUE 97990 (Fig. 2a), and abundant lath-shaped sulfides in the CY chondrites (e.g., Fig. 1e) and the CM1 clast from Kolang (e.g., Fig. 2b). Additional details on the petrography of sulfides are discussed in Schrader et al. (2015, 2016, 2018), Schrader and Zega (2019), Davidson et al. (2019a, b), and King et al. (2019).

Sulfides in each meteorite group are sometimes associated with other opaque minerals such as Fe,Ni metal or magnetite. Fe,Ni metal is commonly associated with sulfides in the H, L, LL, CY (Fig. 1e, f), CR, CO, and CV chondrites. The observation of Fe,Ni metal in sulfides is useful because if the sulfide is troilite, it indicates that the sulfur fugacity of formation was near the iron-troilite (IT) buffer (e.g., Harries and Langenhorst, 2013). In contrast, sulfides in the CK chondrites are commonly associated with magnetite (Fig. 1h). Sulfides in the most aqueously altered CR chondrites also contain magnetite (e.g., Schrader et al., 2015; Singerling and Brearley, 2020).

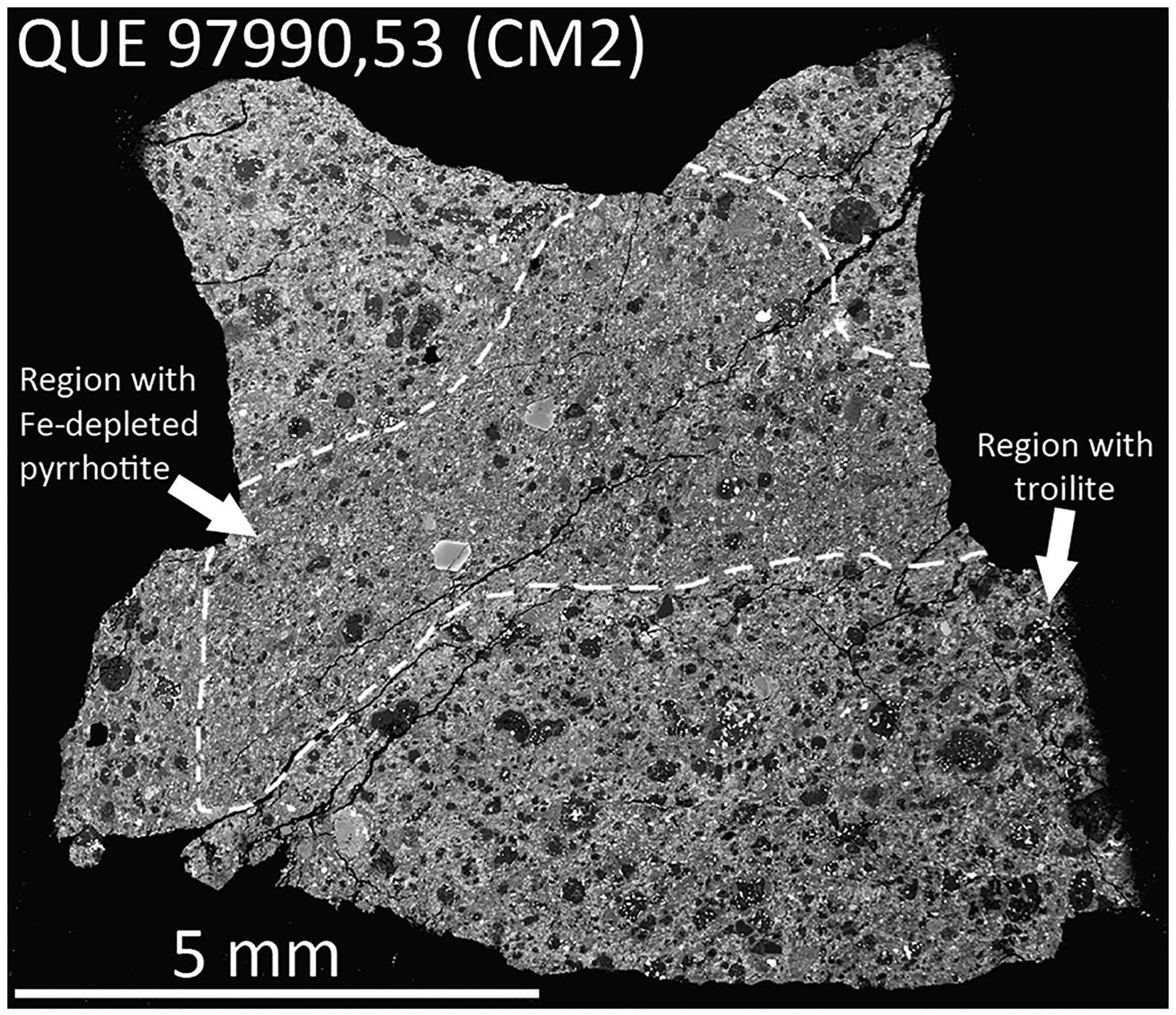

The thin section of QUE 97990 (,53) contains two distinct lithologies, sulfides were analyzed in each lithology and found to have distinct Fe/S ratios (Fig. 3 and EA-1). Two lithologies of the recent fall Kolang (CM1/2) were also analyzed, the typical CM1/2 host material and a CM1 clast. The CM1/2 host material contains abundant phyllosilicates, but also contains primary silicates, Fe,Ni metal, and subhedral and rounded sulfides typical of CM2 chondrites. In contrast the CM1 clast contains chondrules that have been pseudomorphically replaced by phyllosilicates and abundant lath shaped sulfides (Fig. 2b); no silicates or Fe,Ni metal were observed. No compositional differences were identified between pyrrhotite in either lithology, despite the two lithologies having clearly distinct degrees of aqueous alteration and distinct sulfide textures (Tables 3 and 4, and EA-1).

Fig. 3.

BSE image of QUE 97990,53 thin section showing two distinct lithologies. The dominant lithology appears to contain more chondrules and chondrule fragments, whereas the lithology in the center of the thin section appears to contain fewer chondrules and matrix that is brighter in BSE, perhaps indicating more aqueous alteration and more abundant Fe-oxides. Sulfides in the dominant lithology contain troilite (e.g., Fig. 1d), while the central lithology contains Fe-depleted pyrrhotite (e.g., Fig. 2a), indicating more extensive aqueous alteration.

3.2. Types of low-Ni Fe-sulfides observed

Pyrrhotite-group sulfides were identified in all samples studied except the CK4 ALH 85002 and the CK5 and CK6 chondrites (Tables 2a, 2b and EA-1). Pyrite was identified in all CK chondrites studied. In some of the sulfide assemblages that we identified, pure pyrrhotite analyses could not be acquired because of intergrowth between submicron-sized grains of pentlandite at scales below the interaction volume of the EPMA (e.g., common in the R6 LAP 04840 and one sample of the CM2 Aguas Zarcas; Fig. 1c and Tables 3 and 4). To avoid analyses that overlapped with submicron-sized grains of pentlandite, we define any pyrrhotite containing less than 1 wt.% Ni as low-Ni pyrrhotite (Schrader and Zega, 2019); these analyses were used to determine the at.% Fe/S ratios (Tables 3, 4, and EA-1). Analyses of pyrrhotite and pyrite with Ni contents between 1 wt.% and 16 wt.% are given in EA-1, but are not discussed further as they may overlap pentlandite. We report 1630 sulfide analyses; 1102 analyses of low-Ni pyrrhotite (which includes troilite), 475 analyses of high-Ni pyrrhotite (between 1 wt.% and 16 wt.% Ni), and 53 analyses of pyrite. All pyrite analyses are from the CK4, CK5, and CK6 chondrites.

3.2.1. Chondrites containing troilite

The pyrrhotite group sulfide troilite (Fe/S = 1 to 0.98) was found in the H3.10, L3.05, L(LL)3.05, LL3, LL4, LL5, LL6, CO3.00, CV3OxA, CV3OxB, CV3Red, CY, CR1 (Fig. 1g), and CR2 chondrites, the CM2s QUE 97990 (Fig. 1d), Mighei, and Y-793321, the CM-like chondrite Sutter’s Mill, and the R3 chondrite MET 01149 (EA-1). Sulfides in the CR2 chondrites are dominantly troilite, however no troilite was found in the highly aqueously altered anomalous CR chondrite Al Rais (Tables 3 and 4).

3.2.2. Chondrites containing Fe-depleted pyrrhotite

Fe-depleted pyrrhotite (Fe1-xS; Fe/S from < 0.98 to 0.8) was found in the CIs (Fig. 1a), CYs (Fig. 1e, f), the C1-ung MIL 090292, the CR-an Al Rais, some sulfides within CR2 and shock-heated CR2 chondrites, the CM1/2s (Figs. 1b and 2b), the CM2s (e.g. Fig. 2a), the CM-like Sutter’s Mill, the CV3OxA, a single sulfide in the H3.10, some sulfides in the L3.05 and LL chondrites, the R3 to R6 chondrites, and a single grain in the CK4 Karoonda (Fig. 1h; Tables 3 and 4).

3.2.3. Chondrites containing pyrite

Pyrite is common in all CK chondrites studied (EA-1). No troilite was found in the CK chondrites and only a single grain of pyrrhotite was found in the CK4 Karoonda. This pyrrhotite has the lowest Fe/S ratio analyzed here at 0.806 (Table 3). The typical Fe-sulfides found in the CK chondrites were pentlandite and pyrite, which are intergrown with magnetite (Fig. 1h; Schrader et al., 2016).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Minor element compositional variations in low-Ni pyrrhotite

There are minor element compositional variations (e.g., P, Ca, Mn, and Co) in low-Ni pyrrhotite within and among distinct chondrite groups (Tables 2a and 2b). The CV3red Vigarano contains minor P and Ca in its low-Ni pyrrhotite (up to 0.36 wt.% P and 0.55 wt.% Ca), whereas P and Ca are below detection limit (both < 0.02 wt.%) in the CV3OxA (Allende) and CV3OxB (Bali). While we cannot rule out that the P and Ca are not from submicron Ca-phosphates within the sulfide, it is also possible this difference is due to the CV3OxA and the CV3OxB being more altered than the CV3Red. All of the CY chondrites contain low-Ni pyrrhotite with minor amounts of Mn (up to 0.09 wt.%), whereas no other meteorite group studied here consistently contains pyrrhotite with Mn. The CY chondrites that were heated >750 °C (B-7904 and Y-86789) do not contain Co in low-Ni pyrrhotite, while the CY chondrites (Y-82162 and Y-980115) heated between 500 °C and 750 °C contain minor Co (up to 0.04 wt.% Co; Tables 2a, 2b and 3). There is an inverse relationship between Ni and Co in Fe,Ni metal in the CY chondrite Y-86789; Ni-poor metal contains 7.0 wt.% Ni and 1.8 wt.% Co, while Ni-rich metal contains 53.5 wt.% Ni and 0.61 wt.% Co (EA-1). This inverse Ni and Co relationship is consistent with Y-86789 being heated (e.g., Kimura et al., 2008; Davidson et al., 2014a). The most oxidized and thermally metamorphosed chondrites studied here, R and CK chondrites, are the only chondrites that do not contain Si in low-Ni pyrrhotite.

Despite these minor differences, there are no easily recognizable compositional indicators that could be used to match unambiguously an unknown pyrrhotite grain to a particular meteorite group (Tables 2a and 2b). This contrasts with pentlandite, which shows characteristic minor-element signatures within and among groups (Schrader et al., 2016; Schrader and Zega, 2019). Nonetheless, there are significant differences in the Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite within and among some chondrite groups that trend with formation and alteration conditions (see Section 4.2).

4.2. Fe/S ratio variation among petrographic type and meteorite groups

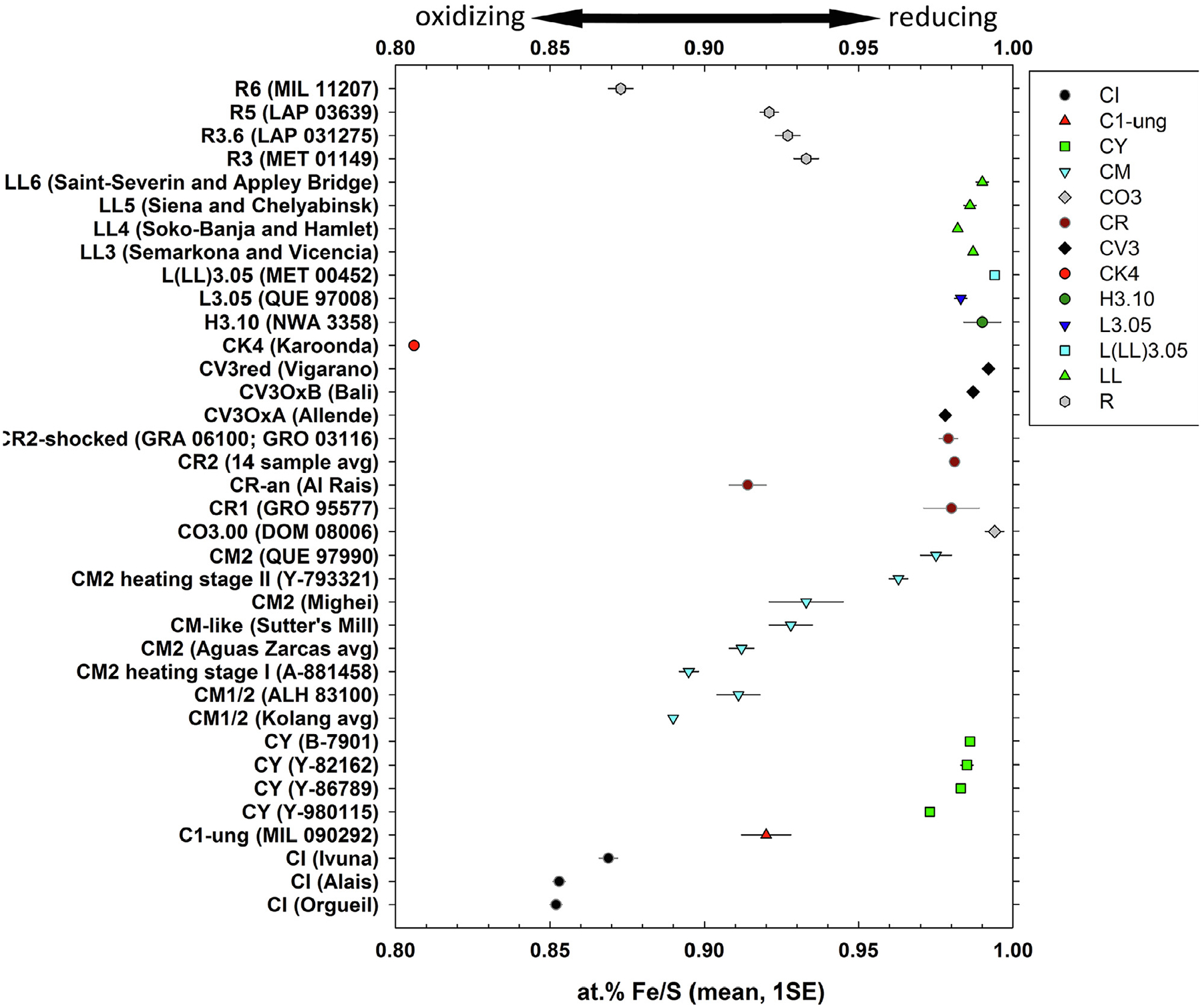

The average Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite varies among meteorite groups and with petrographic type within meteorite groups. Typically, the average Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite decreases with increasing degree of aqueous alteration, consistent with previous work (Bullock et al., 2005; Berger et al., 2011; Harries and Zolensky, 2016; Harries, 2018; Kimura et al., 2020). This lower Fe/S ratio can be explained by Fe loss due to the formation of Fe-oxides and Fe-rich phyllosilicates during aqueous alteration. Troilite occurs in all minimally altered (e.g., CO3.00, CR2, CV3Red, R3, and LL3 chondrites) and some thermally altered chondrites (e.g., CY and LL4 to LL6 chondrites). In contrast, Fe-depleted pyrrhotite is the dominant sulfide in aqueously altered chondrites (e.g., CI, CM1/2, and CM2 chondrites). Sulfides in the R and CK chondrites are an exception to the apparent trend between pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio and degree of aqueous or thermal alteration, which we propose is due to the high oxygen fugacity (fO2) during thermal metamorphism (see Section 4.3). CK chondrite sulfides are almost entirely pyrite and pentlandite, with the single exception of one Fe-depleted pyrrhotite grain in the CK4 Karoonda which has the lowest Fe/S ratio observed in this study (at.% Fe/S = 0.806; Fig. 1h, Table 3). The average Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite decreases with increasing thermal metamorphism in the R chondrites (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The average Fe/S ratio (at.%, mean ± 1SE) of low-Ni pyrrhotite in each chondrite studied here. The Fe/S ratio of ideal troilite is 1.00 and the lowest Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite is 0.8.

The degree of aqueous alteration in carbonaceous chondrites trends with the average Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite. Ordered from smallest to largest value the average Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite in carbonaceous chondrite groups is CK4 < CI < CM1/2 ≤ CR-an ≤ C1-ung ≤ CM2 ≤ CR1 ≈ CR2 ≈ CY ≤ CV3 ≤ CO3.00 (Table 5 and Fig. 4). While this overall trend can mostly be attributed to differences in degree of aqueous alteration, it is likely that internal sample heterogeneities, group variations, thermal and aqueous alteration, and differences in sulfur and oxygen fugacities all contribute to the order of Fe/S ratios.

Table 5.

Average Fe/S and Cations/S at.% values of low-Ni pyrrhotite, ordered by lowest to highest ratio.

| Meteorite Group | avg. Fe/S | 1σ | avg. Cations1/S | 1σ | # of Meteorites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petrographic Type | |||||

| CK4 | 0.806 | – | 0.817 | – | 1 |

| CI | 0.858 | 0.009 | 0.870 | 0.010 | 3 |

| R6 | 0.873 | 0.009 | 0.886 | 0.009 | 1 |

| CM1/2 | 0.901 | 0.015 | 0.910 | 0.014 | 2 |

| CR-an | 0.914 | 0.011 | 0.923 | 0.011 | 1 |

| C1-ung (MIL 090292) | 0.920 | 0.016 | 0.923 | 0.017 | 1 |

| R5 | 0.921 | 0.022 | 0.923 | 0.022 | 1 |

| R3.6 | 0.927 | 0.023 | 0.929 | 0.023 | 1 |

| R3 | 0.933 | 0.022 | 0.936 | 0.022 | 1 |

| CM2 | 0.934 | 0.030 | 0.943 | 0.028 | 6 |

| CV3OxA | 0.978 | 0.004 | 0.979 | 0.004 | 1 |

| CR1 | 0.980 | 0.016 | 0.984 | 0.014 | 1 |

| CR2 | 0.981 | 0.008 | 0.990 | 0.006 | 16 |

| CY | 0.982 | 0.006 | 0.984 | 0.005 | 4 |

| LL4 | 0.984 | 0.007 | 0.984 | 0.007 | 2 |

| L3.05 | 0.983 | 0.007 | 0.985 | 0.006 | 1 |

| LL5 | 0.988 | 0.008 | 0.990 | 0.006 | 2 |

| LL3 | 0.987 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 0.005 | 2 |

| CV3OxB | 0.987 | 0.003 | 0.990 | 0.003 | 1 |

| H3.10 | 0.990 | 0.027 | 0.992 | 0.026 | 1 |

| LL6 | 0.991 | 0.007 | 0.992 | 0.009 | 2 |

| CV3Red | 0.992 | 0.004 | 0.992 | 0.004 | 1 |

| L(LL)3.05 | 0.994 | 0.004 | 0.995 | 0.004 | 1 |

| CO3.00 | 0.994 | 0.008 | 0.996 | 0.006 | 1 |

| Group Averages (if multiple petrographic types) | |||||

| R avg. | 0.914 | 0.027 | 0.918 | 0.022 | 4 |

| CV3 avg. | 0.986 | 0.001 | 0.987 | 0.000 | 3 |

| LL avg. | 0.988 | 0.003 | 0.989 | 0.003 | 8 |

Averages weight each meteorite equally, as some meteorites have more sulfide analyses.

Cations = Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu.

Taking into consideration the observations from all chondrite groups studied, the trend in average Fe/S ratio is significantly more complicated. Including all chondrites studied the order from lowest to highest average Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite, according to petrographic type, is CK4 < CI < R6 < CM1/2 ≤ CR-an ≤ C1-ung ≤ R5 ≤ R3.6 ≤ R3 ≤ CM2 ≤ CV3OxA ≈ CR1 ≈ CR2 ≈ CY ≈ LL4 ≤ L3.05 ≤ LL5 ≤ LL3 ≈ CV3OxB ≤ H3.10 ≈ LL6 ≤ CV3Red ≤ L(LL)3.05 ≈ CO3.00 (Table 5 and Fig. 4). Therefore, using the at.% Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite as a universal proxy for the degree of aqueous or thermal alteration is not warranted.

4.3. Relationship between pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio and aqueous alteration/heating

In some meteorite groups the average Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite decreases with increasing aqueous alteration (e.g., CM chondrites), consistent with previous observations (Bullock et al., 2005; Berger et al., 2011; Harries and Zolensky, 2016; Harries, 2018; Kimura et al., 2020). Troilite is present in all minimally altered (e.g., CR2s, LL3s, CO3.00) and some thermally metamorphosed samples (e.g., LL4 to LL6), indicating troilite is not a product of aqueous alteration. However, there are exceptions to the apparent relationship between the pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio and aqueous alteration, for example: (1) the single pyrrhotite grain observed in the thermally metamorphosed CK4 Karoonda has an Fe/S ratio lower than the most aqueously altered carbonaceous chondrites; (2) the R6 MIL 11207 has a pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio nearly identical to the heavily aqueously altered CI chondrite Ivuna; (3) the average Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite in the R chondrites decreases with increasing degree of thermal metamorphism, in contrast to the LL3 to LL6 chondrites (all contain troilite); (4) despite the CV3OxA, CV3OxB, and CV3Red chondrites having significant differences in their aqueous and thermal histories (e.g., Weisberg et al., 2006, Busemann et al., 2007; Bonal et al., 2020), all contain troilite; and (5) the CR chondrites do not follow an overall trend between pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio and aqueous alteration (Table 4 and Fig. 4). Reasons for these differences are discussed below.

Sulfides are highly susceptible to alteration during aqueous and/or thermal processing. After initial formation, the compositions of pyrrhotite group sulfides and pentlandite can change by low-temperature (<100 °C) equilibration during slow cooling and/or annealing over thousands of years (Etschmann et al., 2004). Sustained parent body temperatures <100 °C may change the compositions of sulfides while brief heating episodes <100 °C (e.g., due to impact heating) may not. Therefore, understanding parent body aqueous and thermal histories of individual meteorites is important for placing the average Fe/S ratios of pyrrhotite in context (Table 3). Multiple CM and CR chondrites were studied that cover a range of aqueous alteration and include some mildly heated samples (Tables 3 and 4). These samples provide a way to test how the Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite varies with increasing degree of aqueous alteration and minor heating within individual meteorite groups.

4.3.1. Pristine and minimally altered samples

The chondrites least altered by parent body aqueous and thermal alteration include H3.10 (NWA 3358), L3.05 (QUE 97008), L(LL)3.05 (MET 00452), and CO3.00 (DOM 08006) chondrites; all of these samples contain troilite and have among the highest average Fe/S ratios found here (Table 5). DOM 08006 is recognized as potentially the most pristine meteorite known and contains primary sulfides that formed during chondrule formation which were not altered on the parent body (Davidson et al., 2019b). Pyrrhotite in DOM 08006 is entirely troilite and has the highest average Fe/S ratio of any meteorite studied here (Table 3). In addition, the presence of pristine Fe,Ni metal in DOM 08006 constrains the parent body temperature to <100 °C and the equilibration temperature of sulfides in DOM 08006 are ~400 °C (Davidson et al., 2019b). Therefore, troilite is a primary phase in DOM 08006 and the parent body temperature of DOM 08006 was not high enough to alter these primary sulfides.

In contrast, the parent body temperatures of NWA 3358 (estimated between 250 to 350 °C; Ebert et al., 2020), MET 00542 (203 ± 70 °C; Cody et al., 2008), and QUE 97008 (<250 °C; Busemann et al., 2007) were high enough that the compositions of primary sulfides may have changed. NWA 3358 (H3.10) is one of the least altered H chondrites known, and while a specific temperature for NWA 3358 has not been constrained, peak temperature estimates for 3.1 ordinary chondrites are between 250 to 350 °C (e.g., Rambaldi and Wasson, 1981; Alexander et al., 1989). In addition, there is an inverse relationship between Ni and Co in Fe,Ni metal from NWA 3358; Ni-poor metal contains 3.9 wt.% Ni and 0.52 wt.% Co, while Ni-rich metal contains up to 51.7 wt.% Ni and <0.10 wt.% Co (EA-1). An inverse Ni and Co relationship in Fe,Ni in chondrites is indicative of mild heating (e.g., Kimura et al., 2008). During this mild alteration on the H chondrite parent body, fluid was present and mild aqueous alteration of NWA 3358 occurred (Ebert et al., 2020). While nearly all low-Ni pyrrhotite in NWA 3358 is troilite, one sulfide grain contained pyrrhotite with a low Fe/S ratio (Fe/S = 0.900; Table 3 and EA-1) that may be additional evidence of limited aqueous alteration of NWA 3358. Both MET 00542 and QUE 97008 have been heated enough that minor changes in the Cr2O3 content of silicates and the metal Co/Ni ratio have been observed (e.g., Grossman and Brearley, 2005; Kimura et al., 2008), indicating that their sulfides were likely altered to some degree. However, if these samples were heated long enough to alter the compositions of their primary sulfides it either did not change the Fe/S of low-Ni pyrrhotite or the conditions they were heated under were at the proper sulfur fugacity and reducing enough to also form troilite (i.e., such as that observed in the LL3, LL4, LL5, and LL6 chondrites; see Section 4.3.5).

4.3.2. CM chondrites

The Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite decreases with increasing aqueous alteration in the CM chondrites (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Pyrrhotite in the most aqueously altered CM chondrites studied here, the CM1/2s ALH 83100 and Kolang, have the lowest Fe/S ratios of the CM chondrites. In contrast the least aqueously altered CM2 studied here, QUE 97990 (a CM2.6; Rubin et al., 2007; Kimura et al., 2008; Alexander et al., 2013), has the highest Fe/S ratio as it contains troilite (Table 3). The Fe/S ratios of pyrrhotite in Aguas Zarcas samples indicate they are heavily aqueously altered, as they have a similar Fe/S ratio to that of the CM1/2 chondrites.

Three CM chondrites studied here have been mildly heated (Table 3). Different samples of the CM-like Sutter’s Mill were heated to between 150 °C and 500 °C (Jenniskens et al., 2012). However, the Sutter’s Mill sample studied here has not undergone noticeable heating that would alter the Cr2O3 content of its silicates (Schrader and Davidson, 2017). Since Sutter’s Mill contains pyrrhotite with a low Fe/S ratio of 0.928, we conclude this resulted from aqueous alteration and that this particular Sutter’s Mill sample (stone SM8) was not heated enough to convert any Fe-depleted pyrrhotite to troilite. The stage I heated CM2 chondrite A-881458 was slightly heated to temperatures below 250 °C (Nakamura, 2005). A-881458 contains only Fe-depleted pyrrhotite similar to that in CM1/2 chondrites, indicating any heating it underwent did not increase the Fe/S ratio of its pyrrhotite or that any heating occurred prior to aqueous alteration. The stage II heated CM2 chondrite Y-793321 was briefly heated after aqueous alteration between 300 °C and 500 °C (Nakamura, 2005) and therefore heating may have modified the Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite that was previously lowered by aqueous alteration. Nakamura (2005) also found troilite in other heated CM2 chondrites, indicating troilite formed during thermal alteration on the CM chondrite parent asteroid.

A thin section of QUE 97990 (,4) was identified as having experienced some minor heating resulting in Cr diffusion in ferroan olivine (Schrader and Davidson, 2017), which suggests the presence of troilite in QUE 97990 may be due to minor heating or QUE 97990 is a breccia that contains relatively pristine and thermally altered components. The thin section of QUE 97990 studied here (,53) contains grains of fizzed sulfide in its matrix (Fig. 2a), suggesting it has been shock heated (fizzed troilite is an indicator of shock heating; e.g., Scott, 1982; Bennett and McSween, 1996) or at the very least that it contains components that have been heated. As most sulfides in QUE 97990 are not fizzed and fizzed sulfides are only present in the matrix, heating may not have been widespread or heated and unheated material may have been mixed via impact gardening and lithified into a breccia in the CM parent asteroid. We consider brecciation likely as: (1) QUE 97990,53 displays multiple lithologies that are consistent with brecciation (Fig. 3); (2) numerous CM chondrites are breccias (e.g., Bischoff et al., 2006); and (3) a bulk isotopic study of QUE 97990 did not indicate heating (Alexander et al., 2013). Troilite in QUE 97990,53 is located in a single chondrule in what appears to be the less altered lithology based on the presence of Fe,Ni metal (Fig. 3), while Fe-depleted pyrrhotite is present in matrix grains in a separate lithology that appears more altered based on a more Fe-rich matrix (Fig. 3). The composition of the fizzed ‘troilite’ is actually Fe-depleted pyrrhotite, perhaps indicating QUE 97990 was aqueously altered after the formation of fizzed troilite by impact heating.

Sulfides in two distinct lithologies of Kolang were studied (the typical CM1/2 material and a CM1 clast); however, the sulfides analyzed in each lithology are Fe-depleted pyrrhotite with indistinguishable compositions (Tables 3 and 4). The sulfide laths observed in Kolang ASU2147_C3c (the CM1 clast) are petrographically similar to those seen in CY chondrites (Figs. 1e vs. 2b), but are compositionally distinct (Table 2a). The sulfide laths in the CY chondrites sometimes have Fe,Ni metal and contain both Fe-depleted pyrrhotite and troilite, whereas the sulfide laths in Kolang only contain Fe-depleted pyrrhotite.

Recently, Kimura et al. (2020) proposed that A 12169, A 12236, and A 12085 are the most unaltered CM chondrites known, with proposed classifications of CM3.0, CM2.9, and CM2.8, respectively. In these samples, low-Ni sulfides are mostly troilite, although Fe-depleted pyrrhotite is present in each sample (Kimura et al., 2020). However, the at.% Fe/S ratios were not provided for low-Ni pyrrhotite in these samples. A 12169 was identified as the least altered CM known and designated as a CM3.0 by Kimura et al. (2020); i.e., only undergoing minimal aqueous alteration and no heating or dehydration (Kimura et al., 2020). The single low-Ni pyrrhotite compositional analysis provided for A 12169 (from Table 4 in Kimura et al., 2020) yields an Fe/S ratio of 0.942. While only a single analysis, this low Fe/S ratio indicates that A 12169 has undergone more extensive aqueous alteration than that of the CO3.00 or most CR2s studied here and similar to other CM2s and the CM1/2 ALH 83100 (Table 5 and EA-1). This is consistent with the conclusion of Kimura et al. (2020) that A 12169 is aqueously altered, but may be inconsistent with a classification of a 3.0 or indicate brecciation.

4.3.3. CR chondrites

The common presence of troilite in CR2 chondrite chondrules is consistent with the observations that CR2 sulfides are mostly primary and that they formed during chondrule cooling between 600 °C and 400 °C (Schrader et al., 2015; Davidson et al. 2019a). Recently, MIL 090657 was recognized as one of the most, if not the most pristine CR chondrites (Davidson et al. 2019a), potentially more pristine than QUE 99177 and MET 00426, which have long been considered the most pristine CR chondrites (e.g., Abreu and Brearley, 2010; Schrader et al., 2011, 2014). The Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite in MIL 090657 is higher than any of the other 16 CR2 chondrites studied here, even QUE 99177 and MET 00426, which further supports the highly pristine nature of MIL 090657 (Table 4) discussed by Davidson et al. (2019a).

There is a trend in the average Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite between the CR2 chondrites and the anomalous CR chondrite Al Rais; Al Rais does not contain troilite and its average Fe/S pyrrhotite ratio is lower than that of all CR2 chondrites studied. Al Rais is recognized as the most aqueously altered CR chondrite, with the exception of the CR1 GRO 95577 (e.g., Weisberg and Huber, 2007). While most CR2 chondrites contain abundant troilite, there are also variations in the Fe/S pyrrhotite ratios within individual CR2 chondrites. Individual pyrrhotite grains in the CR2 chondrites Shişr 033 and NWA 801 have Fe/S ratios as low as those seen in Al Rais (Table 4), perhaps indicating heterogeneity in the degree of aqueous alteration or post-aqueous alteration mixing of lithologies with distinct degrees of aqueous alteration via brecciation (e.g., Weisberg et al., 1993; Schrader et al., 2014).

The shock heated CR2 chondrites GRA 06100 and GRO 03115 were briefly heated >610 °C (e.g., Abreu and Bullock, 2013) and contain fizzed troilite indicating heating (Schrader et al., 2015), but have Fe/S ratios indistinguishable from the other CR2 chondrites. Despite the similar Fe/S ratios, we consider the sulfides in these two shock heated CR2 chondrites to be secondary because the morphologies of their sulfides indicate they were heated.

The CR1 GRO 95577 does not contain pyrrhotite with low Fe/S ratios contrary to what one might expect when compared to the other type 1 chondrites studied here (the CIs, the CM1/2s, and the C1-ung; Table 3). Instead, GRO 95577 contains troilite intergrown with pentlandite (e.g., Fig. 1g) and some Fe-depleted pyrrhotite (Tables 3 and 4). The presence of troilite and the lack of abundant pyrrhotite with low Fe/S ratios in a highly aqueously altered type 1 chondrite may indicate that GRO 95577 experienced heating after aqueous alteration. However, no Fe,Ni metal is associated with the sulfides in GRO 95577, which is unlike that observed by Harries (2018) for heated CM/CI-like chondrites. This may indicate that: (1) GRO 95577 was heated and the lack of Fe,Ni-metal is either a sampling artifact or due to metal loss during terrestrial weathering (GRO 95577 is a weathering grade B); or (2) the troilite in GRO 95577 did not form from the decomposition and S-loss from Fe-depleted pyrrhotite during heating. The troilite in GRO 95577 may result from the decomposition of S-bearing hydrous phases during heating, as originally suggested by Nakamura (2005) for troilite in heated carbonaceous chondrites. The bulk δD of GRO 95577 is significantly lower than other CR chondrites except for the shock-heated CR chondrites (Alexander et al, 2013), but has not previously been considered to be heated. However, based on the relatively low bulk δD and presence of troilite in GRO 95577 we conclude that it was mildly heated. Heating of GRO 95577 may also be consistent with the young formation age of its carbonates compared to those in other CR chondrites (i.e., 12.6 Myr vs. 4.3–5.3 Myr after CAI formation), which Jilly-Rehak et al. (2017) suggested may be due to heating of liquid water by an impact(s) on the CR chondrite parent body.

4.3.4. CY chondrites

The CY chondrites were aqueously altered and then briefly heated; Y-82162 (heating stage III or II) and Y-980115 were heated between 500 °C and 750 °C, and B-7904 and Y-86789 (both heating stage IV) were heated >750 °C (Ikeda, 1992; Matsuoka et al., 1996; Nakamura, 2005; Tonui et al., 2014; King et al., 2019). Since heating occurred after aqueous alteration, any Fe-depleted pyrrhotite that formed in the CY chondrites during aqueous alteration would have been heated and potentially altered. The CY chondrites contain abundant troilite and only minor Fe-depleted pyrrhotite, consistent with the observation that heating after aqueous alteration in carbonaceous chondrites leads to the loss of Fe-depleted pyrrhotite and formation of troilite (e.g., Nakamura, 2005; Harries, 2018). Troilite in B-7904 was proposed to be secondary and the result of decomposition of S-bearing hydrous phases (i.e., tochilinite) during heating (Nakamura, 2005; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013). The two CY chondrites studied here with the lowest average pyrrhotite Fe/S ratios are Y-82162 and Y-980115, which were heated to lower temperatures than B-7904 and Y-86789 (Table 3). The most heated CY chondrites, B-7904 and Y-86789, contain pyrrhotite with the highest Fe/S ratios, demonstrating that heating leads to the formation of troilite. The sulfide grains in the CY chondrites, which are dominantly troilite (EA-1), are commonly associated with Ni-rich and Ni-poor metal (Fig. 1e, f). The association of metal in sulfide grains is somewhat in agreement with the proposed formation of troilite in heated chondrites by Harries (2018). However, Harries (2018) proposed that S loss during heating and decomposition of Fe-depleted pyrrhotite would result in troilite with Ni-poor metal, and the sulfides in heated CY chondrites contain troilite and Ni-poor and Ni-rich metal indicating that their formation during thermal alteration was more complicated.

4.3.5. Thermally metamorphosed LL, R, and CK chondrites

The average Fe/S ratios of pyrrhotite in the three most thermally metamorphosed meteorite groups studied here, the LL, R, and CK chondrites, have distinct trends with degree of thermal metamorphism. The LL3 to LL6 chondrites record parent body temperatures between <220 °C (LL3) and 899 ± 70 °C (LL6; Table 3), but all contain troilite. In contrast, the R chondrites were heated to a range of temperatures up to ≥ 950 °C, but have an inverse relationship between the pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio and degree of thermal metamorphism. The R3 contains pyrrhotite with the highest Fe/S ratio (which includes troilite; EA-1), while pyrrhotite in the R6 has the lowest Fe/S ratio (Table 3). Similarly, the least heated CK chondrite studied here contains a pyrrhotite grain with the lowest Fe/S found in this study, while low-Ni Fe-sulfides in the other CK chondrites are entirely pyrite (EA-1). The differences in the Fe/S ratio trends with increasing thermal metamorphism between these meteorite groups are likely due to differences in their fO2.

Oxygen fugacity is commonly expressed as relative to the iron-wüstite buffer (IW) or to the fayalite-magnetite-quartz buffer (FMQ). Since the iron-wüstite buffer (IW) is approximately 3.5 log units below FMQ (Righter et al. 2006) at ≥1000 °C, they can be readily compared to one another. The equilibrated LL5 and LL6 chondrites were thermally metamorphosed under oxygen fugacities of IW−2.2 to IW−1.7, respectively (Schrader et al., 2016; Schrader and Zega, 2019). Righter and Drake (1996) combined the fO2 calculations for L and LL chondrites and found they range from approximately IW−1.5 to IW−1.25. Since L chondrites are less oxidized than LL chondrites, we exclude the combined data of Righter and Drake (1996) (e.g., Fig. 5a; Righter et al., 2006) from our discussion. Converting LL chondrite fO2 values relative to the IW buffer to the FMQ buffer, we estimate that the fO2 of LL chondrites is FMQ−5.7 to FMQ−5.2. Therefore, the LL chondrites were thermally metamorphosed at relatively reducing conditions compared to the R chondrites (FMQ−3.5 to FMQ; Righter and Neff, 2007), whereas the CK chondrites are the most oxidized chondrite group (FMQ + 2 to FMQ + 4.5; Righter and Neff, 2007).

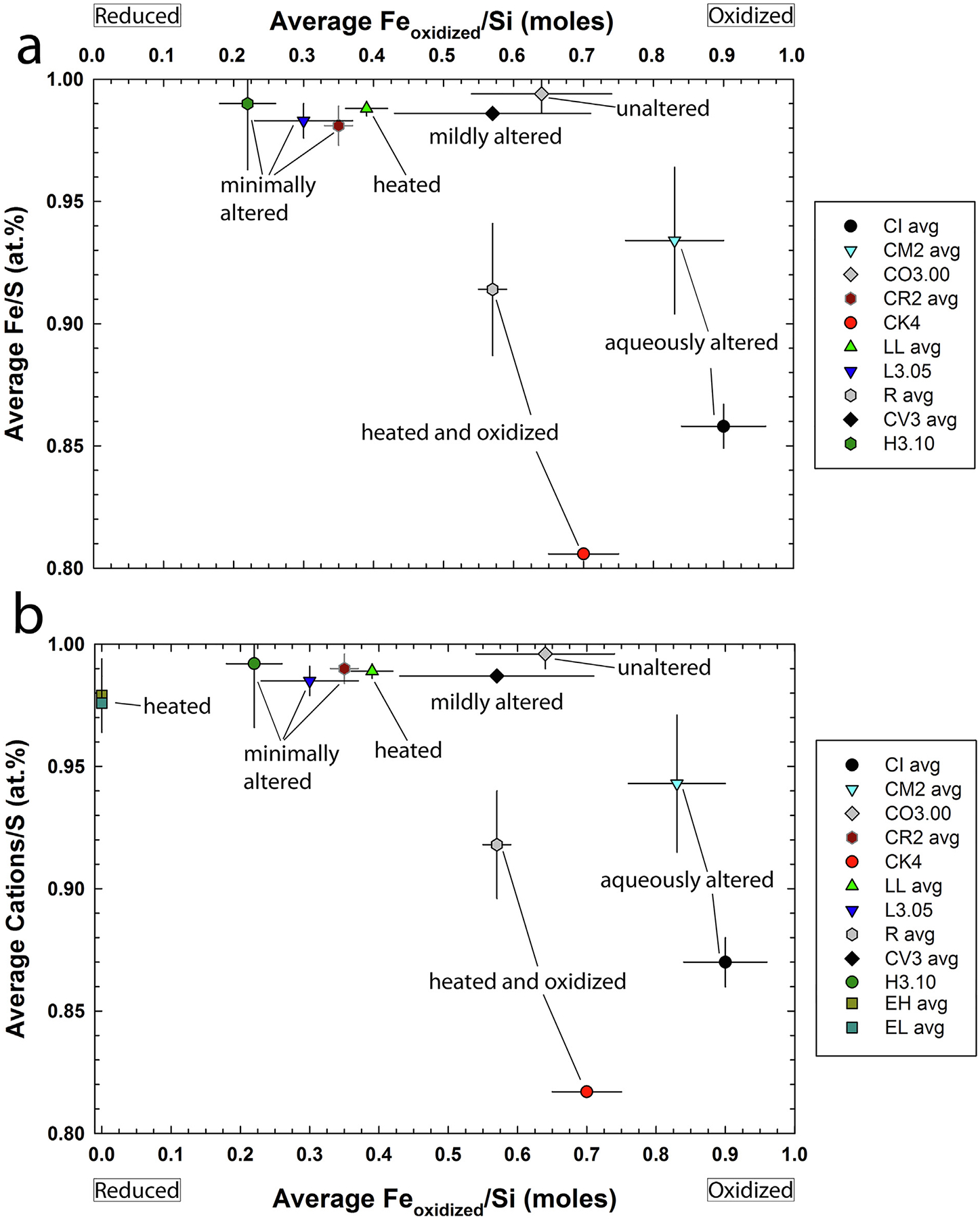

Fig. 5.

Diagram of the average Feoxidized/Si (moles) value of chondrite groups (not the exact samples studied here) vs. (a) the average Fe/S (at.%, ±1σ) of corresponding chondrite groups and (b) vs. the average Cations/S (at.%, ±1σ) of corresponding chondrite groups (Cations = Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu) including troilite from EH and EL chondrites; values in Table 4 Oxidation state of the samples increases as the Feoxidized/Si (moles) value increases. Minimally/unaltered samples (L3.05, CO3.00, and CR2) contain pyrrhotite with high Fe/S ratios (including abundant troilite), while heated and oxidized samples (R and CK chondrites) contain pyrrhotite with lower Fe/S ratios. The CV3 chondrites also only contain pyrrhotite with high Fe/S ratios, despite undergoing a range of mild thermal and aqueous alteration. The LL chondrites were thermally metamorphosed, but under relatively reducing conditions compared to R and CK chondrites. The CM and CI chondrites were aqueously altered under oxidizing conditions and contain pyrrhotite with low Fe/S ratios. Troilite data for enstatite chondrites from the literature; EH data from Keil (1968), Leitch and Smith (1982), Rubin (1983), El Goresy et al. (1988), Piani et al. (2016), and EL data from Keil and Andersen (1965) and Rubin (1984). Average Feoxidized/Si (moles) values from Brearley and Jones (1998) and Righter et al. (2006); original data from Urey and Craig (1953), Larimer and Wasson (1988), Jarosewich (1990), Masson and Wiik (1962a, b), and Yanai (1992). Only meteorite groups studied here that have literature Feoxidized/Si (moles) values are plotted.

The oxidant during thermal metamorphism of the LL, R, and CK chondrites was water. While water was key to the alteration of each of these three meteorite groups, the starting compositions of each meteorite group and the amount of water accreted by their parent asteroids led to distinct alteration conditions (e.g., Rubin, 2005; Righter and Neff, 2007; McCanta et al., 2008; Davidson et al., 2014b; Jones et al., 2014). Although the LL chondrite parent body accreted some water it was still relatively dry compared to the R and CK chondrites, especially as thermal metamorphism progressed (Jones et al., 2014). Since the LL chondrites were relatively dry and oxidation did not significantly vary during thermal metamorphism (Schrader et al., 2016), there was not a noticeable change in the pyrrhotite Fe/S ratio during thermal alteration. In contrast, the R chondrite parent body accreted with sufficient water to result in the formation of OH-bearing minerals in the R6 chondrites LAP 04840 and MIL 11207 (Righter and Neff, 2007; McCanta et al., 2008; Rubin, 2014). Metasomatism in the CK chondrites led to oxidation and the formation of substantial magnetite (e.g., Righter and Neff, 2007; Davidson et al., 2014b). Therefore, the oxidation of both the R and CK chondrites increased with thermal metamorphism. Implications of fO2 for all samples in this study are discussed in Section 4.4.

4.4. Relationship between pyrrhotite Fe/S ratios and oxidation during aqueous or thermal alteration

The presence of troilite or Fe-depleted pyrrhotite in a chondrite is an indicator of the relative fO2 of its formation. This association is the case whether the sample is minimally altered, aqueously altered, and/or thermally metamorphosed, as oxidation can occur in the protoplanetary disk or in the parent body during aqueous or thermal alteration. Only samples that are minimally altered are likely to retain sulfides from their initial formation in the protoplanetary disk (i.e., chondrule formation). For example, troilite is known to be present in samples that formed under reducing conditions (e.g., lunar samples at IW−2 to IW; Righter et al., 2005) and Fe-depleted pyrrhotite is found in relatively oxidized volcanic rocks on Earth (e.g., Whitney, 1984; >IW). Herndon et al. (1975) proposed that troilite was oxidized to Fe-depleted pyrrhotite and magnetite in carbonaceous chondrites. In highly oxidized volcanic rocks, pyrrhotite can oxidize to form pyrite and magnetite (e.g., Whitney, 1984). The same trend between sulfide mineralogy and oxidation is observed in the chondrites analyzed here.

In regards to bulk sample, the least to most oxidized chondrites studied here are as follows: H < L < CR < LL < CV < R < CO < CK < CM < CI (Righter et al., 2006; Righter and Neff, 2007; Fig. 4). CY chondrites are not included in this trend as they were only recently recognized; however, Harries and Langenhorst (2013) estimated the sulfur and oxygen fugacity of alteration for the CY chondrite B-7904 and concluded it was altered at a sulfur fugacity near the IT buffer and at an fO2 near the IW buffer. This order is approximate and minimally altered unequilibrated chondrites are difficult to place in this sequence because they contain chondrules that formed under a wide range of oxygen fugacities in the protoplanetary disk. For example, chondrules from unequilibrated chondrites formed under reducing conditions of IW−4.2 to relatively oxidizing conditions of IW−0.4 (e.g., Zanda et al., 1994; Schrader et al., 2013). However, for the purpose of comparing relative oxidation among meteorite groups this order according to bulk sample is sufficient.

The minimally altered chondrites (CO3.00, CR2, H3.10, and L3.05) formed under a range of oxidation conditions (e.g., Righter et al., 2006; Righter and Neff, 2007; Fig. 5a), but all contain pyrrhotite with high Fe/S ratios (i.e., troilite). The CV3 chondrites all contain troilite, despite experiencing a range of aqueous and thermal alteration. However, despite the subgroup names of reduced and oxidized, the CV3 subgroups record similar parent body fO2 and their differences are likely due to their degree of alteration (Goreva and McCoy, 2012). The LL chondrites all contain troilite regardless of degree of thermal metamorphism (LL3 to LL6), which we conclude is the result of their thermal metamorphism being relatively reducing compared to R and CK chondrites and similar to, or more reducing than, the fO2 at which their chondrules formed (see Section 4.3.5). The R chondrites were metamorphosed under oxidizing conditions (e.g., Righter and Neff, 2007) and contain pyrrhotite with Fe/S ratios significantly lower than in minimally altered samples or the thermally metamorphosed LL chondrites. The CK chondrites are the most oxidized thermally metamorphosed chondrites (e.g., Righter and Neff, 2007) studied here and have the lowest Fe/S ratio, indicating oxidation of Fe into silicates and oxides leads to pyrrhotite with low Fe/S ratios. Similar to that seen in highly oxidized volcanic rocks (e.g., Whitney, 1984), low-Ni sulfides in the CK chondrites are dominantly pyrite (ideally Fe/S = 0.5; Table 3 and EA-1) that is in contact with magnetite (e.g., Schrader et al., 2016). We hypothesize that pyrrhotite was hydrothermally oxidized into pyrite and magnetite during metasomatism of the CK chondrites. The aqueously altered CI and CM chondrites experienced oxidizing conditions during aqueous alteration, resulting in lower pyrrhotite Fe/S ratios (especially the heavily aqueously altered CI chondrites) compared to minimally altered chondrites. Therefore, the Fe/S ratio of low-Ni pyrrhotite can be used as proxy for the oxidation of a sample.

4.4.1. Troilite in the most reduced chondrite groups

The EH and EL chondrites are the most reduced chondrite groups known (i.e., with FMQ between −10 and −8.5; Fogel et al., 1989; Righter et al., 2006) and they contain abundant troilite (e.g., Mason, 1966). Since EH and EL chondrites formed under highly reducing conditions, they often contain Cr, Ti, and Mn contents near or greater than 1 wt.% in troilite (e.g., Brearley and Jones, 1998). Exsolution lamellae of daubréelite (FeCr2S4) and ferroan alabandite ([Mn,Fe]S) in troilite are common in enstatite chondrites (Keil and Andersen, 1965). Therefore, some of the high minor element abundances in EH and EL troilite may be due to EPMA beam overlaps with daubréelite (for Cr) and ferroan alabandite (for Mn). Some analyses contain such high abundances of Cr and Ti (e.g., up to3.10 wt.% Cr; Brearley and Jones, 1998) that the at.% Fe/S ratios of ‘troilite’ in both EH and EL chondrites appear so low (e.g., Fe/S < 0.97) they would not be considered troilite. However, as minor elements can substitute for Fe in sulfides, it is more appropriate to take the ratio of (Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu)/S for enstatite chondrite sulfides. Excluding sulfides that appear to be beam overlaps with daubréelite and ferroan alabandite (sulfide data summarized in Brearley and Jones, 1998), the at.% (Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu)/S ratios are all ~1 (i.e., troilite). The low-Ni pyrrhotite from all other chondrites in this study have such low minor element abundances that their average Fe/S ratios are the same as their average at.% (Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu)/S ratios within 1σ (EA-1). Therefore, to compare these chondrite groups to troilite in enstatite chondrites we use the average at.% (Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu)/S ratios (Fig. 5b), which agrees with the trend with high (Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu)/S ratios in reduced samples and low ratios in oxidized samples.

4.4.2. Sulfide type as an indicator of oxygen fugacity

As discussed above, the at.% Fe/S ratio (or [Fe + Ni + Cr + Ti + Co + Cu]/S) of low-Ni pyrrhotite can be used as a proxy for oxidation of a sample. The presence of troilite, Fe-depleted pyrrhotite, and/or pyrite in a chondrite can provide an estimate on the fO2 at which it formed based on the fO2 of different meteorites that contain each sulfide (Sections 4.3.5 and 4.4). If troilite is present we can estimate that the fO2 the troilite formed at is similar to, or more reducing than, ~FMQ−3.5 (i.e., IW; the minimum fO2 of R chondrites, which contain rare troilite [EA-1]). Intergrowths of troilite and Fe-depleted pyrrhotite are known in meteorites and terrestrial assemblages (e.g., Morimoto et al., 1975; Harries et al., 2011; Harries and Langenhorst, 2013; Schrader and Zega, 2019), therefore an fO2 range exists where troilite and Fe-depleted pyrrhotite are stable. If only Fe-depleted pyrrhotite is present then the fO2 during its formation was between approximately FMQ−3.5 to FMQ + 2 (i.e., IW to IW + 5.5; the minimum fO2 of R chondrites to the minimum fO2 of CK chondrites from Righter and Neff, 2007). If pyrite is present then the fO2 is more oxidizing than FMQ + 2 (IW + 5.5; the minimum fO2 of CK chondrites from Righter and Neff, 2007).