Abstract

The aim of this paper is to examine coping behaviors in the context of discrimination and possible gender-specific differences among a national sample of African American adults in the 2001–2003 National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Results show that in multivariable logistic regression models, African American women (versus African American men) were less likely to accept discrimination as fact of life but were more likely to get mad about experiences of discrimination, pray about it, and talk to someone. After adjusting for differences in the frequency of discrimination, African American women were also significantly more likely to try to do something about it. African American men were more likely to accept discrimination as a fact of life with higher frequency of day-to-day discrimination while women tended to talk so someone with a higher frequency of day-to-day discrimination and lifetime discrimination. These findings suggest gender differences in behavior concerning discrimination.

Keywords: discrimination, psychosocial stress, coping, African American, gender

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been a re-evaluation and social recognition of the way African Americans experience discrimination and racial bias in the United States (Parker, Menasce Horowitz, & Anderson 2020; Quarcoo, 2020). For example, African Americans have experienced discrimination, even when simply engaging in activities such as bird watching (Yang, 2020), barbecuing (Mezzofiore, 2018), and grocery shopping (Thornton, 2020). Numerous cases of people (often, White) calling the police to report African Americans allegedly committing crimes have made headlines, with the most severe of these resulting in death (Asare, 2020). Following Christian Cooper’s experience with racial discrimination while birdwatching in Central Park in 2020, New York passed legislation “that makes it a crime to call 911 or file a false police report in an attempt to intimidate someone because of race” (Castronuovo, 2021, p. 1). New Jersey passed a similar law in response to a couple’s experience with racial discrimination in their own neighborhood (Salo, 2020). At the time of the signing, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy remarked, “Using the threat of a 9–1-1 call or police report as an intimidation tactic against people of color is an unacceptable, abhorrent form of discrimination” (Salo, 2020, p. 1). Viral videos documenting these cases of discrimination offer insight into the microaggressions and discrimination African Americans face, and the passing of legislation designed to deter false reports based on race speak to how frequent and problematic these incidents are (Asare, 2020).

Despite this recent social awakening in the context of police brutality and racial injustices that have captured media attention and garnered mass supporters and protesters for racial equality (Parker, Menasce Horowitz, & Anderson 2020; Quarcoo, 2020), there was already a growing mass of public health and epidemiological literature on the experiences of discrimination among African Americans and especially in the context of health disparities (Krieger, 2014; T. T. Lewis et al., 2015; Lockwood et al., 2018). Discrimination is a psychosocial stressor that has been associated with a plethora of adverse health outcomes that may contribute to health disparities through stress-related biological and physiological processes (Krieger, 2014; Lockwood et al., 2018). Several reviews have captured the scope of these studies, and the multidimensional nature of discrimination (Krieger, 2014; T. Lewis et al., 2015; Lockwood et al., 2018).

Broadly speaking, “to discriminate against someone is to treat that person unfairly based on the group with which that person identifies; groups could be based on categories such as race, age, or sex” (Lockwood et al., 2018, p. 171). Dominance and oppression are key features of discrimination, and discriminatory acts, expressions, and/or policies reinforce the exclusion, disenfranchisement, and unfavorable treatment of individuals on the basis of their identity (Krieger 2014; Lockwood et al., 2018). “Discrimination is disproportionately experienced by individuals who belong to groups that have been historically disenfranchised, oppressed, and marginalized” (Lockwood et al., 2018, p. 171). There are many types of discrimination, though three stand out as particularly relevant to this study: interpersonal discrimination, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination. Interpersonal discrimination refers to “encounters between individuals in which one person acts in an adversely discriminatory way toward another person” (Krieger, 2014, p. 644). The measures of discrimination used in this study are measures of interpersonal discrimination. As such, the questions do not specify the type of discrimination (e.g., whether it was racial or gender discrimination). However, it may be that these experiences are rooted in racial and/or gender discrimination. Racial discrimination and gender discrimination are specific forms of discrimination through which individuals and/or groups are discriminated against on the basis of their racial and/or gender identity (Krieger, 2014). Future research may benefit from assessing reactions to and coping with specific types of discrimination.

African Americans have been, and continue to be, targets of racial discrimination in the United States, and report more frequent and severe experiences of racial discrimination in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups (Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018; Lockwood et al. 2018). Given that African American women are subjected to both racial and gender discrimination (Krieger, 2014), or what Crenshaw (1989: p. 149) refers to as “double discrimination,” as well as discrimination on the basis of being Black women (“not the sum of race and sex discrimination, but as Black women”) it is important to consider how their experiences may result in different reactions to and coping with discrimination in comparison to men. While empirical studies have primarily focused on linking discrimination and health outcomes, there currently lacks research on reactions to and coping with discrimination that may differently affect stress-related biological and physiological processes that underlie health disparities.

Further, across indicators, studies have observed more pronounced associations between discrimination and adverse health among African American women compared to African American men including inflammatory biomarkers (Cunningham et al., 2012), kidney function (Beydoun et al., 2017), psychological distress (Banks et al., 2006), hypertension (Roberts et al., 2008), health-related quality-of-life (Coley et al., 2017), and telomere length (Sullivan et al., 2019). Some research suggests that this may be due to African American women having different experiences of, reactions to, and/or coping differently with experiences of discrimination compared to African American men (Coley et al., 2017; Cunningham et al., 2012). African American women may internalize perceived discrimination more than men leading to differences in mental health and stress related biological and physiological processes that could have more negative health impacts on women compared to men (Coley et al., 2017). Work on African American adolescents suggest that even from a young age, girls may be more likely than boys to report more psychological symptoms on account of their greater likelihood to internalize symptoms; yet cultural norms, the environment, and gender roles may play a role (Carlson & Grant, 2008). For example, it may be that “cultural norms place a high value on women’s strength and perseverance,” which may lead women to externalize more and internalize less in order to display strength (Carlson & Grant, 2008).

The differences could also stem from the notion that African American women, in comparison to men, have a higher prevalence of depression (Williams et al., 2007), have to grapple with intersectionalities, and/or gendered racism (Crenshaw, 1989; Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018; Moody & Lewis, 2019), and are expected to be strong and not ask for help (Abrams et al., 2014). Moreover, African American women often experience gendered racial microaggressions, such as being treated as a stereotype (e.g., “angry Black woman, hypersexualized ‘Jezebel’”), receiving negative comments about how they speak, their hair, skin tone, body, etc., and “being silenced and marginalized in [the] workplace” or in school settings; the more frequent and severe these experiences, the stronger the association with “negative mental and physical health outcomes” (Moody & Lewis, 2019, p. 202). Thus, it is important to understand gender differences in reactions and coping behaviors to psychosocial stressors such as discrimination that may have downstream biological and physiological implications on health disparities.

GENDER DIFFERENCES

African Americans are often discriminated against on the basis of their race (Lewis & Van Dyke 2018; Steers et al., 2019; Utsey et al., 2000). While discrimination, and especially racial discrimination, is correlated with a host of negative mental and physical health outcomes for men and women alike (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Utsey et al., 2000), African American women are especially disadvantaged by the combining effects of both sexism and racism, or gendered racism (Crenshaw 1989; Lewis & Van Dyke 2018; Moody & Lewis 2019). Research suggests that certain tendencies, such as not asking for help and not showing vulnerability, which women are socialized into embracing as part of the Strong Black Woman (SBW) schema (Abrams et al., 2014; Moody & Lewis, 2019), can be particularly harmful for women’s mental and physical health (Moody & Lewis, 2019). The socialization process(es) that African American women go through, which lead to both external and internal expectations of them, particularly in terms of strength, may lead them to be hesitant to turn to others in times of pain, fear, and distress, and hesitant to express anger (Abrams et al., 2014; Moody & Lewis, 2019). Thus, we acknowledge that our expectations for women regarding talking about and getting angry about experiences with discrimination could go either way, given the SBW schema.

With that said, both men and women face pressure to appear strong. Regardless of gender, African Americans may not seek mental health services due to, inter alia, the stigma associated with it and/or the belief that “mental health problems can resolve on their own” (Ward et al., 2013, p. 3; Williams et al., 2007). The inclination to avoid seeking treatment, regardless the reason why, may put both men and women at greater risk for negative mental and physical health outcomes, especially when coupled with experiences of discrimination. However, one coping strategy that both men and women may rely on is turning to their faith, whether by praying or attending church services (Steers et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2013). While African Americans, in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups, tend to be more religious (Chatters et al., 2008; Ellison & Taylor, 1996; Steers et al., 2019), some research suggests that women are more likely to embrace religious coping and pray than men (Chatters et al., 2008; Ellison & Taylor, 1996). Research also shows that men and women report different types of discrimination (Kwate & Goodman, 2015; Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018), and may use different coping strategies (Utsey et al., 2000). While both men and women may prefer avoidance coping (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Utsey et al., 2000), women may be more likely to seek social support than men (Utsey et al., 2000). This may be because of women’s religiosity and religious involvement; religious institutions provide strong social networks (Ellison & Taylor, 1996), and given that women engage in religious coping and pray more than men (Chatters et al., 2008; Ellison & Taylor, 1996), the two reactions (praying and talking to someone/seeking social support) may be connected.

To address the gaps in the current literature, the objective of the current study was to examine whether reactions and coping behaviors to experiences of interpersonal discrimination differ between African American men and African American women using a nationally representative sample of African American adults in the United States. Specifically, we used data from the 2001–2003 National Survey of American Life (NSAL) to examine gender differences and self-reported reactions and coping behaviors (accept as a fact of life, get mad, pray, talk to someone, and try to do something about it) to experiences of interpersonal discrimination.

We hypothesized that African American women would report greater experiences of discrimination since prior research suggests that African American women overlap multiple subordinate social identities based on their race and sex (Coley et al., 2017; T. T. Lewis et al., 2015; Tené T Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018). We also hypothesized that women would be more likely to pray, talk to someone, and get angry about experiences of discrimination. Research suggests that irrespective of race, women internalize negative psychosocial experiences and ruminate about stressors more than men (Coley et al., 2017; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Shull et al., 2016) and this may be particularly true for stressors that are interpersonal in nature, such as discrimination. Research also suggests that women are more likely to seek social support (Utsey et al., 2000), and engage in religious coping and pray than men (Chatters et al., 2008; Ellison & Taylor, 1996).

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Sample participants are from the National Study of American Life (NSAL), part of the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey (CPES), conducted by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan. The NSAL, a nationally representative sample of African Americans, was conducted between 2001 and 2003. All respondents were aged 18 and over. In the first phase, data were collected in face-to-face interviews using a computer-assisted program. The second phase of the study involved completing a self-administrated questionnaire referred to as the NSAL Adult Re-Interview (RIW). Only African American respondents who completed both phases and completed the questions on coping to discrimination were included in the analysis—a total of 1,576 respondents.

Measurements

Reactions to Discrimination

The NSAL asks African American respondents their reactions to experiences of discrimination. The exact wording of the question is as follows: How did you respond to this/these experience(s) of discrimination? Please tell me if you did each of the following things: The five reactions examined as dependent variables are as follows: 1) accepted it as a fact of life; 2) got mad; 3) prayed about it; 4) talked to someone; and 5) tried to do something. Responses were “no” or “yes” for each item. Each of the five questions will be considered as separate dependent variables in the analysis.

Covariates

The primary independent variable was gender since we were interested in estimating whether reactions to discrimination were different between women and men. Other covariates included in our models were selected based on a priori theory that may confound our associations of interest including age, education, region, income, frequency of church attendance, living in a rural setting, frequency of day-to-day discrimination, and frequency of lifetime discrimination. Age was coded as continuous. Education was coded into four categories of school completion: 0–11years, 12 years, 13–15 years, and greater than or equal to 16 years. Region was coded as non-South and South. Southern states include 10 of the 11 original confederate states: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. No data was collected for Arkansas. Income was coded as: less than $9,999; $10,000–$14,999; $15,000–$24,999; $25,000–$49,999; and $50,000 or more. Frequency of religious attendance was coded as: less than once a year, a few times a year, a few times a month, at least once a week, and nearly every day. Respondents were coded as living in a rural area or nonrural area based on the percent of individuals in the county who are designated as living in a rural area according to the U.S. Census.

Day-to Day Discrimination

This scale was adapted from the original 9-item scale developed for use in the Detroit Area Study (Williams et al., 1997) which measures respondents’ experiences with “routine and relatively minor day-to-day interpersonal experiences of unfair treatment.” Nine questions were used to capture the frequency of experiencing unfair treatment: being treated with less courtesy than others; being treated with less respect than others; receiving poorer restaurant service than others; being treated as if you are not as smart as others; others being afraid of you; being perceived as dishonest by others; people acting like they are better than you; being called names and insulted by others; and feeling threatened or harassed. While this scale does not specify certain characteristics, experiences of discrimination may transcend experiences of interpersonal mistreatment due to race/ethnicity and may include occurrences of unfair treatment related to age, sex, physical disability, or other characteristics. Response categories ranged from “never” (score = 1) to “almost every day” (score = 6). Responses were summed and ranged from a low of 9 to a high of 54. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of day-to-day discrimination. Prior studies have shown the scale to be reliable (Williams et al., 1997; Taylor et al., 2004).

Lifetime Discrimination

This scale measures “lifetime discrimination experiences that may have occurred many years ago and that, for the most part, involve major interference with advancing socioeconomic positions” (Kessler et al., 1999, p. 212). Nine questions captured whether respondents received unfair treatment such as being fired from a job; not hired for a job; denied a promotion; hassled by police; discouraged from continuing education by a teacher or advisor; prevented from moving into a neighborhood; life made difficult by neighbors; denied a loan; and received unusually bad service from a repairman. The response categories were no/yes, with total scores ranging from 0 to 9. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of lifetime discrimination. The lifetime discrimination scale is reliable as shown in previous studies (Sternthal et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2004)

Data Analysis

Statistical procedures that accounted for the complex sampling methods and non-response variations of the NSAL were used with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). For descriptive purposes, participants’ characteristics were stratified by sex, and differences tested using chi-squared for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Since the outcome variables describing reactions to discrimination are binary, we estimated models for each of the five reactions to discrimination (accepted it as fact of life; got mad; prayed about it; talked to someone; tried to do something about it) with logistic regression. All analyses were conducted before and after adjusting for possible confounding factors considered a priori and included in sequential models. Our first model included only gender since we were interested in determining whether reactions to discrimination were different between women and men. Next, we added demographic variables including age, education and income (model 2), followed by the addition of religious attendance, country region, and rural setting (to adjust for potential differences in contextual influence of place, model 3). Models 4 and 5, adjusted for differences in the frequency of discrimination, day-to-day and lifetime, respectively. In a separate analysis, we determined whether coping responses differed by gender and differences in experiences of discrimination by including gender-by-discrimination interaction terms in the logistic regression models. We explored interactions for gender and two forms of discrimination: 1) day-to-day discrimination and 2) lifetime discrimination. The significance level for main effects and interaction effects was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Descriptive Characteristics

There were 1,573 African Americans in the analytic sample. The mean age was 41 years (range 18–78) and 54% were women (Table 1). Men and women did not significantly differ in educational attainment, income, region, or by rural status. However, there was a significant difference in religious attendance. In general, women had greater frequency of religious attendance compared to men. Descriptive statistics for experiences of discrimination and reactions to discrimination are presented in Table 2. Men had significantly higher experiences for day-to-day discrimination and lifetime discrimination, compared to women; however, women were significantly more likely to get mad, pray, and talk to someone about their experiences of discrimination. A greater prevalence of men responded that they accept discrimination as a fact of life; although this was only a marginal difference compared to women.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, 2001–2003 National Survey of American Life (n = 1576).

| Total Sample (n = 1576) |

Women (n = 1041) |

Men (n = 535) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, wt. mean (SD) | 40.5 (0.6) | 40.1 (0.61) | 41.0 (0.84) | 0.35 |

| Education, n (wt. %) | 0.67 | |||

| 0–11 years | 394 (23.4) | 262 (23.6) | 132 (23.1) | |

| 12 years | 581 (36.3) | 382 (36.7) | 199 (35.8) | |

| 13–15 years | 373 (25.6) | 246 (26.4) | 127 (24.7) | |

| ≥ 16 years | 228 (14.7) | 151 (13.3) | 77 (16.4) | |

| Income, n (wt. %) | <.0001 | |||

| Less than $9,999 | 299 (15.2) | 228 (18.4) | 71 (11.4) | |

| $10,000 – $14,999 | 195 (10.2) | 143 (11.9) | 52 (8.2) | |

| $15,000 – $24,999 | 330 (19.2) | 233 (21.5) | 97 (16.4) | |

| $25, 000 – $49,999 | 464 (31.4) | 282 (29.0) | 182 (34.2) | |

| $50, 000 or more | 288 (24.1) | 155 (19.2) | 133 (29.8) | |

| Religious Attendance, n (wt. %) | <.0001 | |||

| Less than once a year | 149 (12.0) | 85 (9.3) | 64 (15.3) | |

| Few times a year | 311 (22.5) | 179 (19.1) | 132 (26.6) | |

| A few times a month | 382 (26.4) | 253 (26.2) | 129 (26.6) | |

| At least once a week | 534 (34.7) | 396 (39.7) | 138 (28.6) | |

| Nearly every day | 81 (4.5) | 64 (5.7) | 17 (2.9) | |

| Region, n (wt. %) | 0.29 | |||

| North | 685 (50.2) | 436 (48.6) | 249 (52.1) | |

| South | 891 (49.8) | 605 (51.4) | 286 (48.0) | |

| Rural Setting, n (wt. %) | 0.39 | |||

| Rural | 607 (34.8) | 410 (35.7) | 197 (33.8) | |

| Urban | 955 (65.2) | 620 (64.3) | 335 (66.2) |

Table 2.

Reactions to Discrimination, 2001–2003 National Survey of American Life (n = 1576).

| Total Sample (n = 1576) |

Women (n = 1041) |

Men (n = 535) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accept it as Fact of Life, n (wt. %) | 0.07 | |||

| No | 594 (36.4) | 410 (39.3) | 184 (33.0) | |

| Yes | 979 (63.6) | 630 (60.7) | 349 (67.0) | |

| Got Mad, n (wt. %) | 0.005 | |||

| No | 891 (57.3) | 556 (52.7) | 335 (62.8) | |

| Yes | 684 (42.7) | 485 (47.3) | 199 (37.2) | |

| Prayed About It, n (wt. %) | <.0001 | |||

| No | 545 (38.9) | 304 (31.3) | 241 (48.0) | |

| Yes | 1030 (61.1) | 737 (68.7) | 293 (52.0) | |

| Talked to Someone, n (wt. %) | 0.0002 | |||

| No | 812 (52.2) | 503 (47.0) | 309 (58.3) | |

| Yes | 762 (47.8) | 537 (53.0) | 225 (41.7) | |

| Tried to do Something About It, n (wt. %) | 0.19 | |||

| No | 1118 (70.3) | 731 (68.7) | 387 (72.3) | |

| Yes | 458 (29.7) | 310 (31.3) | 148 (27.7) | |

| Day-to-Day Discrimination, wt. mean (SD) | 23.1 (0.3) | 22.4 (0.3) | 23.9 (0.5) | <.0001 |

| Lifetime Discrimination, wt. mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.05) | 2.2 (0.1) | <.0001 |

Logistic Regression Analyses

Accepted Discrimination as a Fact of Life

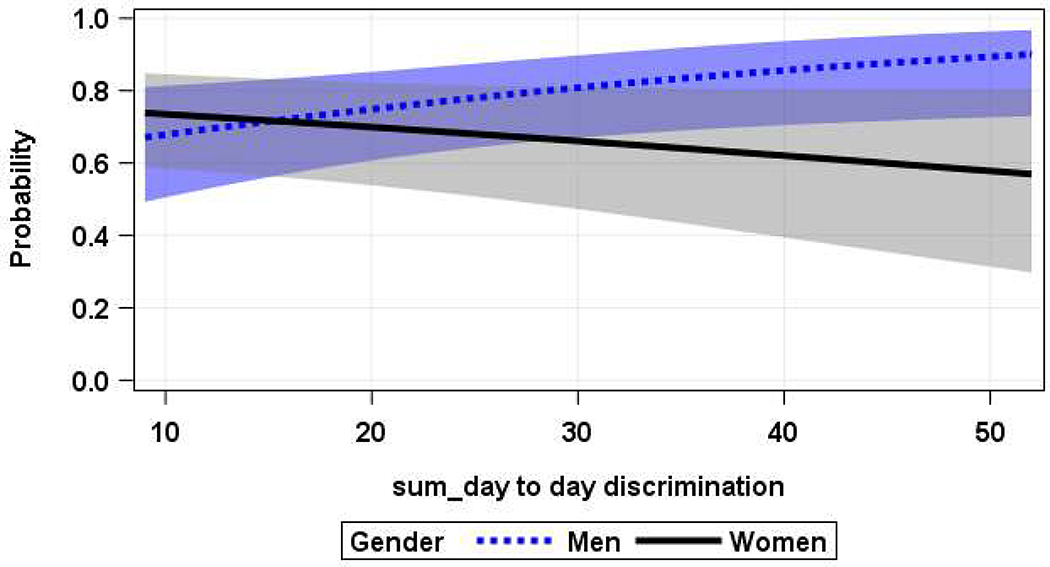

There were significant gender differences for accepting discrimination as a fact of life (Table 3) in multivariable models adjusting for differences in demographic characteristics, religious attendance, region, and rural setting (model 3). More specifically, women were 33% less likely (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.49, 0.91; p-value =0.01) to accept discrimination as a fact of life. Results were similar even after adjusting for differences in experiences of discrimination (models 4 and 5). However, there were significant differences between women and men on accepting discrimination as a fact of life with increases in day-to-day discrimination (p-value of gender*day-to-day discrimination interaction (p = 0.02) (Table 4, Figure 1). More specifically, men were significantly more likely to accept discrimination as a fact of life with increases in experiences of day-to-day discrimination (OR: 104; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.07; p-value = 0.04), while there was a decrease, but not statistically significant odds of accepting discrimination as a fact of life among women (OR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96, 1.01; p-value = 0.16).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for Reactions and Coping Behaviors to Experiences of Discrimination For Women Compared to Men, NSAL

| Women vs. Men (Reference) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | ||

| Accept as Fact of Life | ||

| Model 1 | 0.76 (0.57, 1.03) | 0.08 |

| Model 2 | 0.77 (0.58, 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Model 3 | 0.67 (0.49, 0.91) | 0.01 |

| Model 4 | 0.67 (0.48, 0.93) | 0.02 |

| Model 5 | 0.65 (0.46, 0.90) | 0.02 |

| Got Mad | ||

| Model 1 | 1.52 (1.12, 2.06) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.58 (1.16, 2.17) | 0.01 |

| Model 3 | 2.04 (1.49, 2.79) | <.0001 |

| Model 4 | 2.29 (1.71, 3.07) | <.0001 |

| Model 5 | 2.37 (1.67, 3.36) | <.0001 |

| Prayed About It | ||

| Model 1 | 2.03 (1.52, 2.70) | <.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1.96 (1.45, 2.64) | <.0001 |

| Model 3 | 1.55 (1.12, 2.16) | 0.01 |

| Model 4 | 1.57 (1.12, 2.22) | 0.01 |

| Model 5 | 1.65 (1.13, 2.41) | 0.01 |

| Talked to Someone | ||

| Model 1 | 1.58 (1.23, 2.03) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.53 (1.21, 1.94) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1.58 (1.17, 2.12) | 0.004 |

| Model 4 | 1.64 (1.19, 2.27) | 0.004 |

| Model 5 | 1.83 (1.31, 2.56) | 0.001 |

| Tried to Do Something | ||

| Model 1 | 1.19 (0.91, 1.55) | 0.20 |

| Model 2 | 1.16 (0.89, 1.50) | 0.26 |

| Model 3 | 1.26 (0.96, 1.65) | 0.10 |

| Model 4 | 1.40 (1.05, 1.88) | 0.03 |

| Model 5 | 1.61 (1.20, 2.17) | <.0001 |

Model 1: gender

Model 2: Model 1 + age, education, income

Model 3: Model 2 covariates + frequency of religious attendance, region, and rural setting

Model 4: Model 3 covariates + day-to-day discrimination

Model 5: Model 3 covariates + lifetime discrimination

Table 4.

Gender Specific Estimates from Interaction effects

| Women | Men | P-value of gender- discrimination interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Accept as a Fact of Life | |||

| Day-to-day discrimination | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.07)† | 0.02 |

| Lifetime discrimination | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | 0.90 |

| Got Mad | |||

| Day-to-day discrimination | 1.06 (1.03, 1.08)‡ | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07)† | 0.36 |

| Lifetime discrimination | 1.20 (1.09, 1.32)† | 1.24 (1.11, 1.38)† | 0.60 |

| Prayed About It | |||

| Day-to-day discrimination | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05)† | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 0.85 |

| Lifetime discrimination | 1.21 (1.06, 1.37)† | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) | 0.29 |

| Talked to Someone | |||

| Day-to-day discrimination | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08)† | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.08 |

| Lifetime discrimination | 1.31 (1.18, 1.45)‡ | 1.11 (0.98, 1.26) | 0.06 |

| Tried to do Something About It | |||

| Day-to-day discrimination | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08)† | 1.03 (1.01, 1.06)† | 0.31 |

| Lifetime discrimination | 1.32 (1.19, 1.47)‡ | 1.27 (1.12, 1.43)† | 0.56 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.0001

ORs are from fully adjusted Model 5 + discrimination-by-gender interaction

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities for Accepted Discrimination as Fact of Life with 95% Confidence Intervals: Gender * Day-to-Day Discrimination

Got Mad about Experiences of Discrimination

Compared to men, women were 104% (OR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.49, 2.79; p-value = <.0001) more likely to get mad about experiences of discrimination in multivariable models adjusting for differences across demographic characteristics, religious attendance, region, and rural setting (Table 3, model 3). Gender differences were similar in subsequent models, although more pronounced after adjusting for experiences of discrimination. More specifically, women were 129% and 137% more likely to get mad about these experiences after adjusting for differences in day-to-day discrimination (model 4) and lifetime discrimination (model 5). There was no effect modification of gender and frequency of experiences of discrimination (Table 4).

Prayed about Experiences of Discrimination

Women were also more likely to pray about experiences of discrimination compared to men (Table 3). More specifically, after adjusting for demographics, religious attendance, and rural setting, women were 55% more likely to pray about it (OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.12, 2.16; p-value = 0.01) (model 3). These gender differences were also similar in subsequent models, although more pronounced after adjusting for differences in frequency of discrimination (models 4 and 5). These gender differences were not modified by the frequency of discriminatory experiences (Table 4).

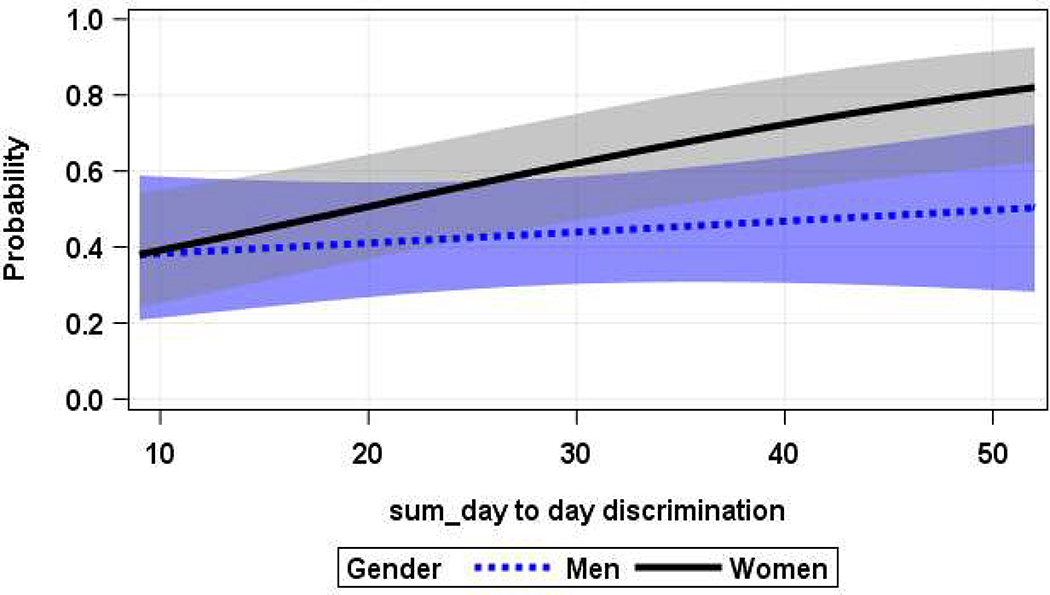

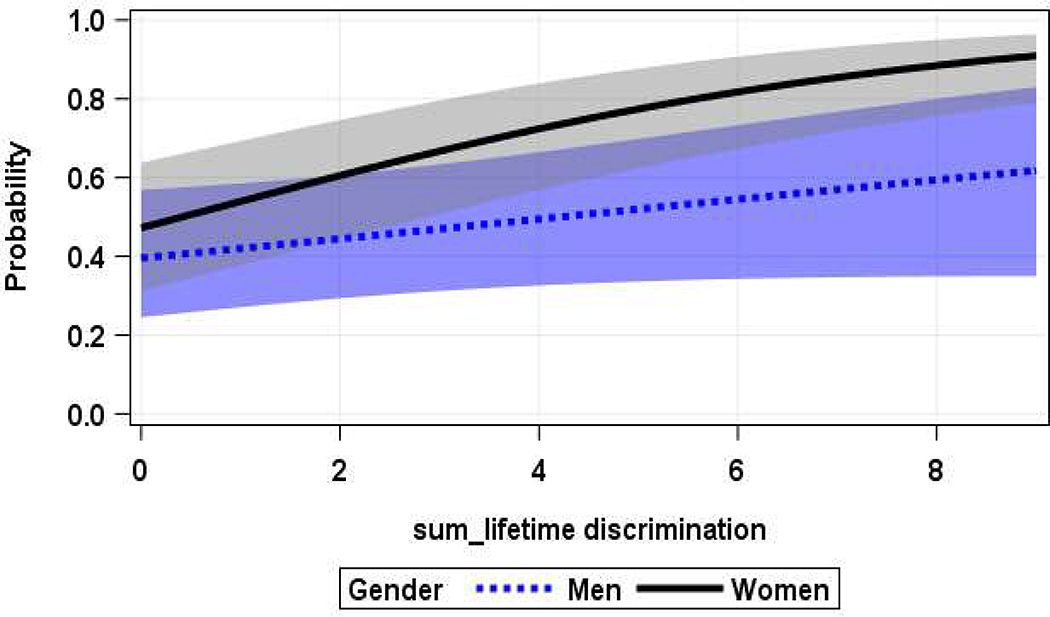

Talked to Someone

Women were also 58% more likely to talk to someone about experiences of discrimination (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.17, 2.12; p-value = 0.004), in multivariable models adjusting for differences across demographic characteristics, religious attendance, region, and rural setting (Table 3, model 3). These findings were robust across subsequent models, and also more pronounced after adjusting for the frequency of experiences of discrimination (models 4 and 5). There were marginally significant interaction effects for gender and the frequency day-to day discrimination (p-value = 0.08) and lifetime discrimination (p-value = 0.06) such that the association was greater and significant for women only (Table 4). In other words, as the frequency of discrimination increased, women had higher odds of talking to someone while there was no significant association among men (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2.

Predicted Probabilities for Talked to Someone with 95% Confidence Intervals: Gender * Day-to-Day Discrimination

Figure 3.

Predicted Probabilities for Talked to Someone with 95% Confidence Intervals: Gender * Lifetime Discrimination

Tried to do Something about Experiences of Discrimination

After adjusting for differences in experiences of discrimination, women were also significantly more likely to try to do something about it (OR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.88; and OR: 1.61; 95% CI: 1.20, 2.17, respectively). These gender differences were not modified by the frequency of discriminatory experiences (Table 4).

Results of all covariates across models are presented in Supplemental Tables 1–5.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that African American men reported a higher frequency of discrimination compared to African American women. However, there were specific gender reactions to coping with discrimination. In multivariable models adjusting for differences in demographic characteristics, religious attendance, region, and rural setting, African American men were more likely to accept discrimination as a fact of life while African American women were more likely to get mad, pray about it, and talk to someone. African American women were more likely to try to do something about it after additionally adjusting for differences in the frequency of discriminatory experiences. In addition, some of these associations were moderated by the frequency of discriminatory experiences. African American men were more likely to accept discrimination as a fact of life with higher frequency of day-to-day discrimination while women tended to talk to someone with a higher frequency of day-to-day discrimination and lifetime discrimination.

These findings raise important questions and bring attention to possible gender-specific differences in coping with psychosocial stressors and stress physiology that require further exploration. These gender differences in coping can impact risks and protective factors resulting in health inequalities between men and women and biopsychosocial interactions. African American women have a disproportionate burden of psychological health and there is growing recognition that psychological and emotional stress are important in women’s disease vulnerability (Banks et al., 2006; Beydoun et al., 2017; Coley et al., 2017; Cunningham et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2008). Research suggests that women are more vulnerable to psychosocial stress, having greater activation of stress processes (Bangasser & Valentino, 2012; Hallman et al., 2001). Some studies suggest that this may be due to African American women having different experiences of, reactions to, and/or coping differently with experiences of discrimination compared to African American men (Coley et al., 2017; Cunningham et al., 2012). Indeed, our results show that African American women and men have different reactions to and cope differently with experiences of discrimination. This may be explained, in part, by the different forms of discrimination African American men and women face. Previous work shows that women report interpersonal incivilities more often than men, while men report more experiences of discrimination associated with the police and profiling (Kwate & Goodman, 2015; Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018). While we are unable to test for more specific forms of discrimination, we believe the findings of previous work (e.g., Kwate & Goodman, 2015) may help explain why men would be more resigned to accept discrimination as part of life than women, given discriminatory experiences with the police, for example, may be more physically threatening to a man than interpersonal incivilities are to a woman. However, we also acknowledge that the differences in reactions to and coping with discrimination may be a product of the double discrimination that women face, and the processes of gendered racial socialization (Crenshaw, 1989; Lewis & Van Dyke, 2018; Moody & Lewis, 2019). In the current study, our results are based on responses to measures of discrimination that are not race specific and do not have a physical attribute ascribed to the experiences. Thus, future research may consider exploring gender differences in reactions to and coping with specific types of discrimination (e.g., racial and/or gender discrimination).

Other studies have shown similar results as our finding that African American men experience greater (racial) discrimination than African American women (Banks et al., 2006; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). However, previous work has found that while women report fewer incidents of major lifetime discrimination than men, they report similar experiences with day-to-day discrimination (Kwate & Goodman, 2015). To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically present gender differences in coping and reactions to discrimination. With that said, other studies have shown that certain coping behaviors to discrimination are associated with adverse health outcomes including blood pressure (Krieger & Sidney, 1996) and cardiovascular disease (Chae et al., 2010). Krieger and Sidney’s (1996). These findings suggest that being able to talk about unfair treatment may lower individuals’ likelihood to experience elevated blood pressure in comparison to an internalized response wherein one accepts it as a part of life and/or keeps it to him/herself. Chae et al. (2010) found that lower levels of internalized, negative beliefs about one’s racial group and experiences of discrimination increase the risk for cardiovascular disease. However, they also found that the risk for cardiovascular disease was highest for African American men with high levels of internalized, negative beliefs about one’s racial group who reported no experiences of discrimination (Chae et al., 2010). While interesting, this finding is consistent with some of the results reported by Krieger and Sidney (1996).

It is possible that African American men, in accepting discrimination as a part of life, may be so resigned to discrimination that they simply do not choose to react to it in the ways that African American women do, because they have either become immune to it (given the frequency at which they experience it), or because they have decided it is beyond their control and their energy and time is better invested in other things (Sullivan, 2020). For African American men, this finding may be indicative of a loss of hope, or a reluctance to react in such a way that may put them at risk, whether mentally or physically (Krieger & Sidney, 1996). For example, Krieger and Sidney (1996) suggest that while expressing their feelings may be validating for women, men may not feel as free or safe to express how hurt or angry they actually feel. This difference may also be explained by differences in prayer use, religious coping, and seeking social support, with women being more likely than men to engage in these behaviors (Chatters et al., 2008; Ellison & Taylor, 1996; Utsey et al., 2000). In addition, men’s reluctance to express emotions may stem from socialization processes rooted in traditional masculinity ideology, which discourages expressing both positive and negative emotions (Hammond, Banks, & Mattis, 2006). Regardless the reason why, not talking about experiences with discrimination could negatively affect the mental health of African American men, which in turn could impact their physical health – whether in the form of increased risk for elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, or in the form of behaviors adopted to cope with it (such as drinking or smoking).

For African American women, our findings may reflect a greater sense of optimism that discrimination is not, or should not be, a part of life, and is possibly something within their control. However, in a prior study examining long-term effects of discrimination on the health behavior of middle-aged African American women, Gerrard et al. (2018) found that racial discrimination can result in externalizing (e.g., becoming angry or hostile) and/or internalizing reactions (e.g., becoming depressed or anxious), and that both reactions have health consequences. Specifically exploring middle-age, non-urban, and African American women from two states, Gerrard et al. (2018) found that with internalizing responses to discrimination, African American women were more likely to be anxious, depressed, avoid thinking or doing something about their experience with discrimination, drink more often, and report problematic drinking after the incident than participants who did not embrace an avoidant coping style. On the other hand, African American women with externalizing responses to discrimination may turn to alcohol (and drink more frequently) to cope with stress related to discriminatory experiences, but coping differently (e.g., thinking/doing something about it) may enable them to avoid alcohol-related issues such as problematic drinking (Gerrard et al., 2018).

Gerrard et al. (2018) also found that having a strong support network may prevent African American women from suffering the same health consequences associated with internalizing responses to discrimination that women with a weak support network face. When considering this research and how it applies to our findings, it may be that African American women, who in our study were found to be more likely (than African American men) to get mad, pray, try to do something, and talk to someone about discrimination, report more externalizing responses while African American men report more internalizing responses. Consequently, without a strong support network or healthy coping styles, African American men may be at greater risk for depression, anxiety, and problematic drinking than African American women. However, African American women may be at greater risk for drinking more frequently, and experiencing more anger and hostility (Boynton et al., 2014; Gerrard et al. 2012). Either way, internalizing or externalizing responses may negatively affect the health of the individual experiencing discrimination, regardless of gender, just in different ways.

The results of prior studies suggest that other factors, such as support networks and coping styles (Gerrard et al., 2018; Gerrard et al., 2012), or the type of discrimination and the environment in which it occurs, may play a role in the effects that certain reactions to discrimination have on individuals (Carter & Forsyth, 2010). For example, Krieger and Sidney (1996) found differences between working and professional class individuals in their responses to unfair treatment, wherein the latter may have more resources and feel more capable of doing something about it than the former. A more thorough examination of these and other potential moderators would enable us to better understand the consequences of reactions to discrimination.

There are several strengths of this study worth mentioning. First, no current study, to our knowledge, has used data from a nationally representative survey among African American adults in the U.S. that includes respondents’ coping behaviors to discrimination. Further, this is also the first study to empirically examine gender differences in coping with discrimination. However, there are also several limitations worth noting. The NSAL is a cross-sectional survey, and experiences of discrimination and coping were not assessed across the life-course. Also, discrimination was only measured at the individual-level excluding other experiences such as at the institutional-level (Williams, 1999). As noted in the introduction, discrimination comes in many forms and both the Everyday Discrimination Scale and the Lifetime Discrimination Scale asked about unfair treatment without regard to a specific attribute such as race. It is important to note; however, that the Everyday Discrimination Scale asked one follow-up question that asked respondents to choose the main reason for discriminatory experiences (i.e., ancestry, gender, race, age, religion, sexual orientation). However, we did not look at differences across reasons for experiences of discrimination in these analyses as we were interested in all experiences regardless of attribute. Future research may benefit from disentangling these responses.

Conclusion

Among a nationally representative sample of African American adults in the U.S., we found gender-specific coping behaviors to experiences of discrimination. In adjusted models, African American men were more likely to accept discrimination as a fact of life, and African American women were more likely to get mad, pray, talk to someone, and do something about it. The NSAL provided a unique opportunity to study coping behaviors and gender differences that may help understand downstream physical and mental health disparities among African Americans. It is possible that these gender-specific differences in coping with psychosocial stressors, such as discrimination, affect physiological and health processes. These heterogeneous reactions with experiences of discrimination should be recognized by medical providers and public health experts so that tailored interventions can focus on these gender differences. Future studies should examine gender differences in coping behaviors to psychosocial stressors with physiological stress processes and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Dr. Samaah Sullivan is supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers: K12HD085850, K01HL149982, L30HL148912, U54AG062334, and UL1TR002378. The authors of this article are solely responsible for the content of this paper. The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of this study, in the collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review or approval of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, & Belgrave FZ (2014). Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the ‘strong Black woman’ schema. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(4), 503–518. doi: 10.1188/0361684314541418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asare JG (2020, May 27). Stop calling the police on Black people Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/janicegassam/2020/05/27/stop-calling-the-police-on-black-people/?sh=3ef5983864c0

- Bangasser DA, & Valentino RJ (2012). Sex differences in molecular and cellular substrates of stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 32(5), 709–723. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, & Spencer M (2006). An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal, 42(6), 555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun MA, Poggi-Burke A, Zonderman AB, Rostant OS, Evans MK, & Crews DC (2017). Perceived discrimination and longitudinal change in kidney function among urban adults. Psychosom Med, 79(7), 824–834. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, & Grant KE. (2008). The roles of stress and coping in explaining gender differences in risk for psychopathology among African American urban adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 28(3), 375–404. doi: 10.1177/0272431608314663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Forsyth J (2010). Reactions to racial discrimination: Emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 183. [Google Scholar]

- Castronuovo C (2021, March 11). First lawsuit over allegedly false race-based police report filed in New York. The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/542721-first-lawsuit-over-allegedly-false-race-based-police-report-filed-in-new [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Adler NE, & Syme SL (2010). Do experiences of racial discrimination predict cardiovascular disease among African American men? The moderating role of internalized negative racial group attitudes. Soc Sci Med, 71(6), 1182–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, & Lincoln KD (2008). Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3), 371–386. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley SL, Mendes de Leon CF, Ward EC, Barnes LL, Skarupski KA, & Jacobs EA (2017). Perceived discrimination and health-related quality-of-life: gender differences among older African Americans. Qual Life Res. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1663-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(8), 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Seeman TE, Kawachi I, Gortmaker SL, Jacobs DR, Kiefe CI, & Berkman LF (2012). Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the association between self-reported experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and inflammation in the CARDIA cohort of 4 US communities. Soc Sci Med, 75(5), 922–931. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Taylor RJ (1996). Turning to prayer: Social and situational antecedents of religious coping among African Americans. Review of Religious Research, 38(2), 111–131. doi: 10.2307/3512336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Fleischli ME, Cutrona CE, & Stock ML (2018). Moderation of the effects of discrimination-induced affective responses on health outcomes. Psychol Health, 33(2), 193–212. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1314479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Weng CY, & Wills TA (2012). Coping with racial discrimination: the role of substance use. Psychol Addict Behav, 26(3), 550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0027711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallman T, Burell G, Setterlind S, Oden A, & Lisspers J (2001). Psychosocial risk factors for coronary heart disease, their importance compared with other risk factors and gender differences in sensitivity. J Cardiovasc Risk, 8(1), 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP, Banks KH, & Mattis JS (2006). Masculinity ideology and forgiveness of racial discrimination among African American men: Direct and interactive relationships. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, (55), 679–692. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9123-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR. (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav, 40(3), 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2014). Discrimination and health inequities. Int J Health Serv, 44(4), 643–710. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, & Sidney S (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health, 86(10), 1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwate NOA, & Goodman MS (2015). Racism at the intersections: Gender and socioeconomic differences in the experience of racism among African Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(5), 397–408. doi: 10.1037/ort0000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, & Williams DR (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 11, 407–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Tené T, & Van Dyke ME (2018). Discrimination and the health of African Americans: The potential importance of intersectionalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 0963721418770442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood KG, Marsland AL, Matthews KA, & Gianaros PJ (2018). Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular health disparities: a multisystem review and health neuroscience perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1428(1), 170–207. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzofiore G (2018). A white woman called police on black people barbecuing. This is how the community responded. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/22/us/white-woman-black-people-oakland-bbq-trnd/index.html

- Moody AT, & Lewis JA (2019). Gendered racial microagressions and traumatic stress symptoms among Black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 201–214. doi: 10.1177/0361684319828288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: the role of gender. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 8, 161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Horowitz JM, & Anderson M (2020, June 12). Amid protests, majorities across racial and ethnic groups express support for the Black Lives Matter movement. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/

- Quarcoo A (2020, June 9). Three takeaways on the protests for racial equality. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/09/three-takeaways-on-protests-for-racial-equality-pub-82021

- Roberts CB, Vines AI, Kaufman JS, & James SA (2008). Cross-sectional association between perceived discrimination and hypertension in African-American men and women: the Pitt County Study. Am J Epidemiol, 167(5), 624–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo J (2020, September 1). New Jersey makes it a crime to make race-based false reports to 911. The New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/09/01/new-jersey-makes-it-illegal-to-falsely-call-911-based-on-race/ [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, & Shelton JN (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J Pers Soc Psychol, 84(5), 1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull A, Mayer SE, McGinnis E, Geiss E, Vargas I, & Lopez-Duran NL (2016). Trait and state rumination interact to prolong cortisol activation to psychosocial stress in females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 74, 324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers M-LN, Chen T-A, Neisler J, Obasi EM, McNeill LH, & Reitzel LR (2019). The buffering effect of social support on the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress among church-going African-American adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 115(2019),121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, & Williams DR (2011). RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH: How Much Does Stress Really Matter? 1. Du Bois review: social science research on race, 8(1), 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JM. (November2020). Does Region Matter on African Americans’ Reaction to Discrimination?: An Exploratory Study. In Martin Lori (Ed.), Introduction to Africana Demography. Boston, MA: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Hammadah M, Al Mheid I, Shah A, Sun YV, Kutner M, Ward L, Blackburn E, Zhao J, Lin J, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V, & Lewis TT (2019). An investigation of racial/ethnic and sex differences in the association between experiences of everyday discrimination and leukocyte telomere length among patients with coronary artery disease. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 106, 122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TR, Kamarck TW, & Shiffman S (2004). Validation of the Detroit Area Study Discrimination Scale in a community sample of older African American adults: the Pittsburgh healthy heart project. International journal of behavioral medicine, 11(2), 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton C (2020, October 7). White woman calls police on Black man placing groceries in his car in Ohio. Black Enterprise. https://www.blackenterprise.com/white-woman-calls-police-on-black-man-placing-groceries-in-his-car-in-ohio/ [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL, & Cancelli AA (2000). Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78(Winter), 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, Wiltshire JC, Detry MA, & Brown RL (2013). African American men and women’s attitude toward mental illness, perceptions of stigma, and preferred coping behaviors. Nurse Res, 62(3), 185–194. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31827bf533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR (1999). Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 896, 173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol, 2(3), 335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzales HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, & Jackson JS (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64(3), 305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A (2020, May 28). Christian Cooper accepts apology from woman at center of Central Park confrontation. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/christian-cooper-accepts-apology-woman-center-central-park/story?id=70926679

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.