Abstract

Glutamate has dual roles in metabolism and signaling; thus, signaling functions must be isolatable and distinct from metabolic fluctuations, as seen in low-glutamate domains at synapses. In plants, wounding triggers electrical and calcium (Ca2+) signaling, which involve homologs of mammalian glutamate receptors. The hydraulic dispersal and squeeze-cell hypotheses implicate pressure as a key component of systemic signaling. Here, we identify the stretch-activated anion channel MSL10 as necessary for proper wound-induced electrical and Ca2+ signaling. Wound gene induction, genetics, and Ca2+ imaging indicate that MSL10 acts in the same pathway as the glutamate receptor–like proteins (GLRs). Analogous to mammalian NMDA glutamate receptors, GLRs may serve as coincidence detectors gated by the combined requirement for ligand binding and membrane depolarization, here mediated by stretch activation of MSL10. This study provides a molecular genetic basis for a role of mechanical signal perception and the transmission of long-distance electrical and Ca2+ signals in plants.

A mechanosensitive channel may confer hydraulic input into wound-induced electrical and calcium signaling in Arabidopsis.

INTRODUCTION

Plants and animals use metabolites such as glutamate and their receptors in electrical signaling (1–4). In animal synapses, restriction of the effective volume and efficient removal of glutamate from the synaptic space are key to keeping ambient glutamate levels between cells low (~0.5 to 5 μM) such that glutamate signals can be perceived. Mammalian glutamate receptors [ionotropic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors and metabotropic mGluR receptors] have a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of ~1 mM, while N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors are activated at low concentrations (EC50 ~ 3 μM) (4). By contrast, the intercellular space between plant cells is orders of magnitude larger, with ambient glutamate concentrations of ~1 mM (5, 6). Glutamate receptor–like proteins (GLRs) can be activated by a variety of amino acids including glutamate (7, 8), although presently the EC50 of plant GLRs is not known, nor are the mechanisms for massive release of glutamate into the apoplasmic space required to register a signal above such a high background.

Plants transmit signals between organs as an early warning of possible threats, e.g., local wounding or insect attack. Wounding is sufficient to trigger three types of long-distance signals: chemical, electrical, and hydraulic. Chemical signaling via cytosolic calcium (Ca2+) and apoplasmic reactive oxygen species is well established (9–13). Electrical signaling had been controversial until Farmer’s group provided the first genetic support for a role of GLRs in the propagation of slow wave potentials (SWPs; Fig. 1A) (3). Four clade 3 GLR (GLR3) paralogs, expressed in phloem and xylem, have been implicated in long-distance wound signaling (3, 14). Farmer et al. (15) proposed the squeeze cell hypothesis, in which wounding causes rapid axial changes of hydrostatic pressure in the xylem that, in turn, cause slower, radially dispersed changes of pressure associated with activation of a clade 3 GLR–dependent signaling pathway that prepares distal leaves for imminent attack. Such pressure waves could carry compounds released from wounded cells, as suggested by Malone in his “hydraulic dispersal” hypothesis (16). Notwithstanding, plants must be able to distinguish glutamate signals from metabolic fluctuations in glutamate levels. Coincident detection of additional cues, such as concomitant pressure waves, could contribute to signal identification (17).

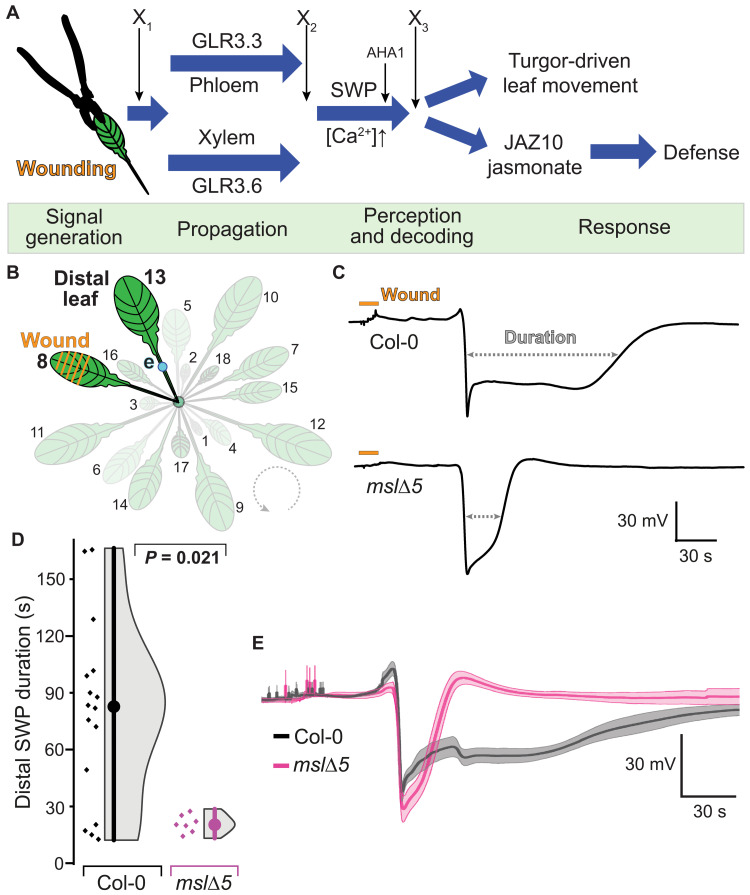

Fig. 1. Wound-induced slow wave potentials (SWPs) in distal leaves of Arabidopsis mslΔ5 and Col-0.

(A) Hypothetical wound signaling network. Severe wounding of L8 triggers a signal that is transmitted to L13 via electrical and calcium waves as well as mechanical cues. Distinct GLRs function in parallel signaling pathways in xylem and phloem (2, 35). Four phases of wound signaling can be assigned (green): signal initiation, distal transmission, perception and decoding of the signal, and triggering of responses (defense and leaf movements). AHA1 functions in SWP repolarization (46). X1 refers to a process or protein that initiates the chain of events, e.g., apoplasmic glutamate elevation; X2 refers to a protein involved in signal propagation; X3 refers to a putative signal receptor. (B) Schematic representation of experimental setup. L8 was wounded, and surface potential dynamics were recorded on the petiole of L13 (distal leaf). e = electrode (blue dot). (C) Representative SWP recordings in distal leaves after wounding (orange bar) Col-0 or mslΔ5 plants. Quantitative analysis of SWP parameters extracted from raw traces provided in fig. S2. (D) Duration of distal SWP (median ± SEM: Col-0: 82.6 ± 12.1 s; mslΔ5: 20.3 ± 1.7 s). Displayed P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test (n = 7 to 16). (E) Individual SWP recordings were aligned by derivative minima and averaged; averaged SWP trace of mslΔ5 was superimposed onto averaged SWP trace of Col-0; error bands, SEM.

RESULTS

To identify additional components of wound-induced systemic signaling, and to test whether stretch-activated channels may play roles in electrical signaling, we analyzed SWPs in distal leaves using surface electrodes to screen >20 Arabidopsis lines carrying mutations in genes that encode ion channels [including stretch-activated MscS (mechanosensitive channel of small conductance)–like (MSL) mechanosensitive channels], receptor-like kinases, NADPH (reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidases, and enzymes involved in glutamate metabolism (table S1 and fig. S1). SWPs triggered by wounding leaf 8 (L8) were recorded with surface electrodes attached to the petiole of L13 (Fig. 1B). While most mutants did not show obvious differences, an MSL quintuple mutant (mslΔ5 with T-DNA insertions in MSL4, MSL5, MSL6, MSL9, and MSL10) (18) produced ~4-fold shortened SWPs relative to Col-0 control plants (Fig. 1, C to E, and table S2 and S3). Other SWP features, such as maximal hyperpolarization, rate of depolarization (first-order derivative), and the amplitude of the initial depolarization, showed no statistically significant differences compared to Col-0 SWPs (fig. S2 and table S3).

The SWP phenotype of the mslΔ5 mutant indicates that one or more MSLs function in wound-induced leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling. The five MSLs that carry insertions in mslΔ5 (4, 5, 6, 9, and 10) are all known or predicted to localize to the plasma membrane (18). Notably, mslΔ5 showed no other obvious defects in development or mechano-responses (18). While SWPs of the msl9 single and msl4;5;6 triple mutants were indistinguishable from Col-0, msl10-1 single mutants showed similar short-duration SWPs as found in mslΔ5 (Fig. 2, A to C). The SWP repolarization maximum was also significantly different from Col-0 (Fig. 2D). An independent T-DNA allele, msl10-2, showed a similar SWP phenotype as msl10-1 (Fig. 2, B to D, and fig. S3).

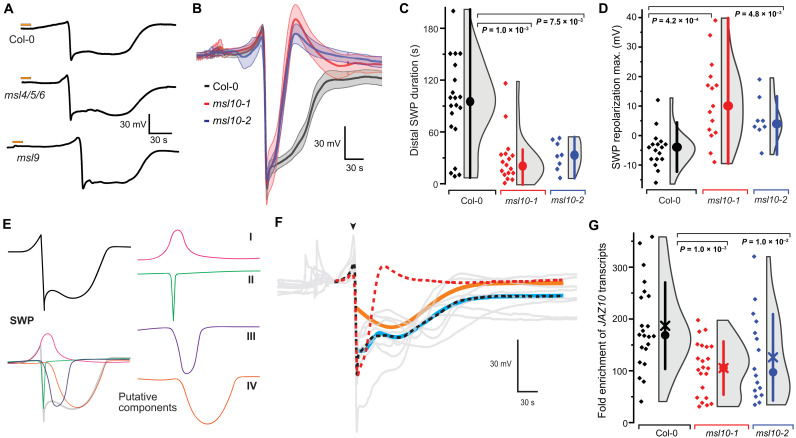

Fig. 2. Wound-induced SWPs in distal leaves of msl10 mutants.

(A) Representative SWP recordings in distal leaves after wounding (orange bars) of Col-0, msl4/5/6, and msl9 mutant plants. (B) Averaged SWP recordings aligned by derivative minima (n = 5 to 6; error bands, SEM). (C) SWP duration (median ± SEM: Col-0: 99.6 ± 11.8 s, msl10-1: 21.7 ± 7.0 s, msl10-2: 32.7 ± 5.9 s). (D) SWP repolarization maxima (median ± SEM: Col-0: −4.0 ± 1.5 mV, msl10-1: 12.5 ± 3.6 mV, msl10-2: 4.0 ± 2.7 mV; n = 8 to 17). Analysis of other SWP parameters provided in fig. S3. (E) Hypothetical model in which SWP is broken down into four distinct components, I to IV. (F) Quantitative comparison of mutant and Col-0 SWP curves. Col-0 and mutant response curves differ by a component describable through a single gamma function. Gray lines are individual wild-type (WT) response curves. The red dashed line is the mean response curve of the mutants. Combining this empirical mutant response curve with a single gamma distribution function (orange line) and a constant downshift results in an excellent fit (cyan line) to the mean of Col-0 response curves [black dashed line; root mean square error (RMSE) = 0.864, corresponding to 1.9% of the range of the data]. Fitting was done downstream of the major depolarization event (arrowhead). (G) JAZ10 mRNA levels in L13 of msl10 mutants as determined by qRT-PCR. Circle, median; ×, mean. All P values displayed were calculated using Mann-Whitney U test.

Surface electrodes report aggregate electrical activities from the underlying tissues. Analysis of variations between SWPs in Col-0 and msl10 mutants may indicate that the traces represent a superposition of at least four different components: an initial hyperpolarization (I), rapid depolarization and initial recovery that resemble an action potential (II), and two slower depolarization waves (III and IV; Fig. 2E) (3, 19, 20). Averaged SWP traces of the mslΔ5 mutant had characteristics that were compatible with the interpretation that component IV was lost, producing the apparent shortening, an effect also observed in the glr3.3 and glr3.6 single mutants (Fig. 1E and fig. S1) (3). Quantitative comparison of mutant and Col-0 SWPs using a modeling approach substantiated the initial trace decomposition, i.e., differences in SWPs could be explained by loss of a single component in the mutant (Fig. 2F). Visual inspection of SWP traces of glr3 mutants indicates that component IV is also lacking in these mutants (3).

As predicted based on the model in Fig. 1A, MSL10 would be required for defense gene induction. Similar to the case of glr3 mutants (3), mRNA levels of the defense marker JAZ10 were significantly reduced in L13 in response to wounding of L8 in both msl10 alleles when compared to Col-0 (Fig. 2G). In both msl10 alleles, the T-DNA was inserted in the first exon of MSL10, causing a substantial reduction in MSL10 mRNA levels (fig. S4). Insertions and additional mutations were validated by whole-genome sequencing of msl10-1 (fig. S5 and tables S4 and S5). T-DNA insertion into GLR gene family members could be excluded as a cause for the SWP phenotype. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis indicated that the msl10 mutant phenotype was also not caused by a negative impact on GLR3.1, GLR3.3, and GLR3.6 mRNA levels in msl10-1 (fig. S4). Together, these data show that MSL10, similar to the individual GLR3s, plays a critical role in the proper formation of SWPs in distal leaves, likely acting up- or downstream of the GLRs.

MSL10 is one of two mechanosensitive channels in the plasma membrane jointly responsible for the predominant mechanosensitive channel activity in protoplasts from Arabidopsis roots and is required for cell swelling responses of Arabidopsis seedlings (18, 21). MSL10 has a conductance of ∼100 pS, a moderate anion preference, slow activation kinetics (time constant, 100 to 1000 ms) (22–24), and strong hysteresis (i.e., MSL10 closes at much lower tension thresholds than required for activation) (22), meeting several expectations for a mechanoelectrical signal transducer, e.g., for detection of a wound-induced pressure wave. MSLs are distant homologs of the Escherichia coli MscS (25), which is activated by membrane tension in response to acute hypoosmotic shock, thereby protecting bacteria from rupture (25, 26). MscS forms a homoheptameric ion channel made up of subunits each containing three transmembrane (TM)–spanning helices and a cytoplasmic C-terminal domain that forms a large water-filled internal cavity (27). Allosteric interactions between the helices and phospholipids are possibly involved in gating (as implied by the “force-from-lipid” hypothesis) (28). Phylogenetic analyses of MscS homologs suggest that Arabidopsis MSL10 is more closely related to fungal and yeast homologs than to its Arabidopsis paralog MSL1, whose structure has been recently resolved by cryo–electron microscopy (figs. S6 and S7) (29, 30). A combination of homology and de novo structure modeling based on coevolutionary contact predictions was used to generate a composite model of MSL10 (fig. S8). A constrained channel is formed by TM6, where F553 forms a possible vapor lock and G556 forms a kink, as in MSL1 (fig. S8, A and B) (29). The structural relevance of F553 and G556 is consistent with conductivity defects observed in the respective MSL10 mutants (23). S640 stabilizes interactions between neighboring chains via a hydrogen bond to E715 (fig. S8A). S640A mutation leads to gain of function, highlighting the importance for MSL10 function (31, 32). A possible EF-hand motif was identified in the extended intracellular loop between TM4 and TM5 (fig. S9). The predicted EF-hands raise the possibility that MSL10 activity may be modulated by Ca2+, as in fungal EF-MscS channels (33, 34).

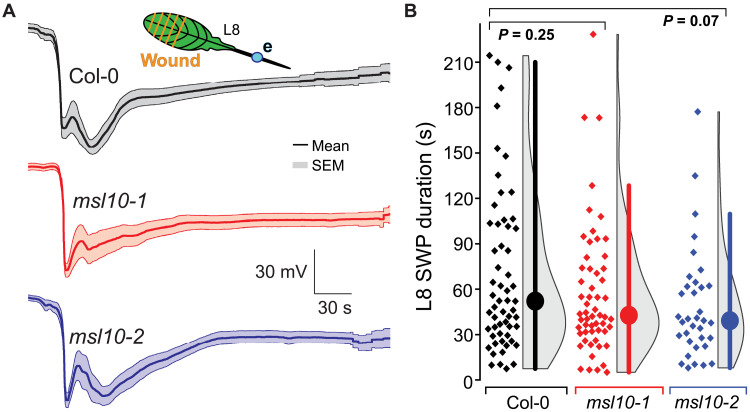

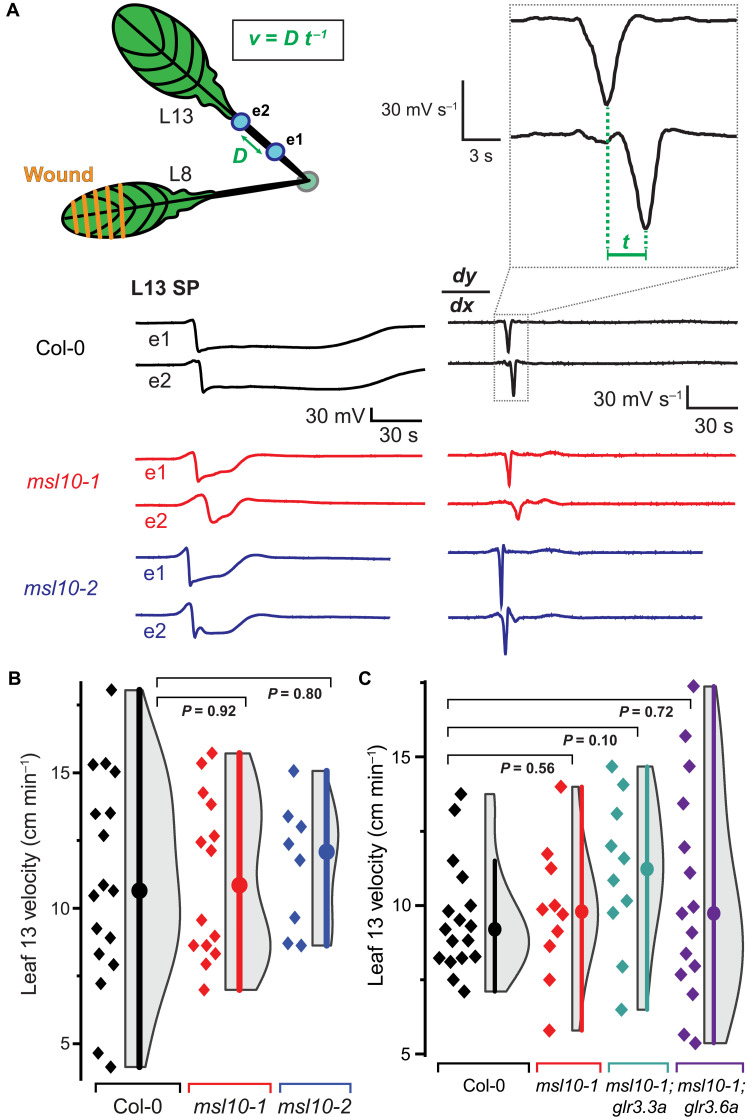

While GLRs likely play a role in chemical signaling, mechanosensitive channels may monitor pressure changes generated by distal wounding. The observed difference in the SWP observed in L13 of msl10 mutants could emanate from a defect that occurs already in L8, during the transmission, or in L13 (Fig. 1A). Wounding of L8 caused variable SWPs (fig. S10); quantitative analyses showed no significant differences in SWP duration when comparing Col-0 and the msl10 mutant, indicating that MSL10 acts either during transmission or in signaling in L13 (Fig. 3). Likely, local agonist accumulation is much higher than in distal leaves, activating GLR3s independently of MSL10 function. Quantification of the velocity at which the SWP traveled between two electrodes attached sequentially on the L13 petiole showed no significant difference when comparing msl10 mutants and Col-0 (Fig. 4). MSL10 function was therefore tentatively assigned to the distal leaf. By contrast, glr3.3;3.6 double mutants had shortened SWPs already at the wounding site (19). MSL10 could act up- or downstream of GLRs in L13 (Fig. 1A). To evaluate a possible interplay between MSL10 and GLR3s, tissue specificity of MSL10 was analyzed and compared to that of the GLR3s, glutamate conductance by MSL10 was evaluated, crosses were performed to explore genetic interactions of MSL10 with GLR3s, and wound- and glutamate-induced Ca2+ waves were quantified in msl10 single and msl10;glr3 double mutants.

Fig. 3. L8 SWP characteristics including duration are statistically indistinguishable among msl10-1 and msl10-2 mutant plants compared to Col-0 controls.

(A) Averaged L8 SWP traces (n = 12 to 17; error bands, SEM). e = electrode (blue dot). (B) Quantification of aggregated L8 SWP duration from multiple experiments. Displayed P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. Violin plots and statistics as in Fig. 1. See fig. S10 for raw traces and statistical summaries of individual experiments.

Fig. 4. L13 SWP velocities are unaffected.

(A) Schematic showing of wounded L8 and placement of two electrodes (e1 and e2, blue dots) on the petiole of distal L13. Example SWP recordings are shown below the schematic, and the derivative (dy/dx) is shown to the right. Velocity (v) was calculated as the distance (D) between two electrodes (e1 and e2) divided by the time (t) between derivative minima. (B) Quantification of velocity of SWP in msl10 mutants versus Col-0 (median and SEM: Col-0: 10.7 ± 1.0 cm min−1, msl10-1: 10.9 ± 0.8 cm min−1, msl10-2: 12.9 ± 0.8 cm min−1). (C) Quantification of SWP velocity in L13 of msl10-1 single mutant or msl10-1;glr3 double mutants in comparison to Col-0. Violin plots and statistics as in Fig. 1 (n = 8 to 17). All P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test.

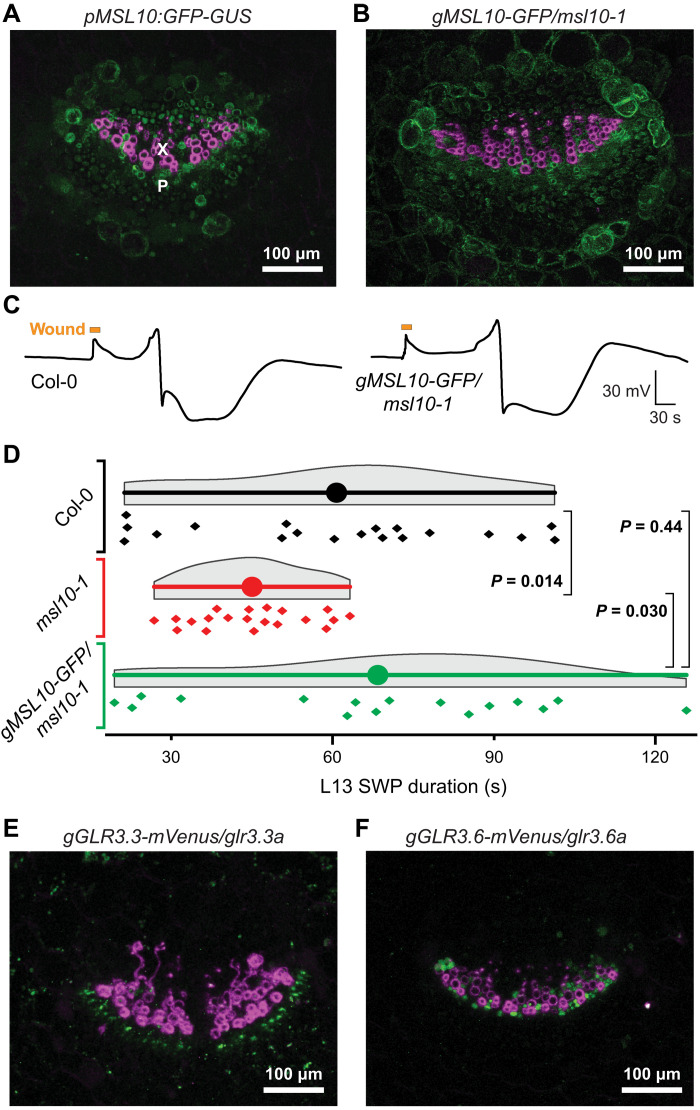

Fluorescence of translational GLR3.3–enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fusions was detected mainly in the phloem, while GLR3.6-EGFP fusions were expressed in xylem contact cells (2). A parallel analysis of transcriptional and translational GLR3.1, GLR3.3, and GLR3.6 fusions in petioles of L13 detected GUS (β-glucuronidase) activity of GLR3.1-GUS in both xylem and phloem, GLR3.3-GUS in the phloem, and GLR3.6-GUS in the xylem (35). To evaluate which cell types may contribute to MSL10-mediated signaling, lines expressing either transcriptional or translational MSL10:GUS-GFP fusions were analyzed in the petiole of L13, i.e., the location where surface electrodes are placed (18). Point-scanning confocal microscopy of transverse petiole sections detected GFP fluorescence broadly across the vasculature, including both phloem and xylem, and the translational fusion construct rescued the msl10 phenotype (Fig. 5, A and D, and fig. S11). Expression of MSL10 thus overlaps with each of the three characterized GLR3 isoforms—GLR3.1, GLR3.3, and GLR3.6—in the distal leaves (Fig. 5, E and F).

Fig. 5. Expression of GFP-tagged transcriptional and translational MSL10 in leaf vascular bundles.

(A) Composite image of a transverse petiole section showing fluorescence from a GFP-GUS transcriptional reporter fused to MSL10 promoter (pMSL10) in green and lignin autofluorescence indicating xylem vessels in magenta. Image is a maximum intensity z-stack projection of confocal data. X, xylem; P, phloem. (B) Composite image of a transverse petiole section showing fluorescence from a MSL10 genomic fragment (gMSL10) tagged with GFP in green and lignin autofluorescence indicating xylem vessels in magenta. GFP-tagged construct is expressed in the msl10-1 mutant background. (C) Representative SWP traces from an experiment comparing Col-0 plants to msl10-1 mutants transformed with translational gMSL10-GFP reporter construct. (D) Statistical analysis of an independent experiment comparing Col-0, msl10-1, and gMSL10-GFP/msl10-1 SWP durations in L13. Displayed P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test (n = 16 to 19). Statistical analysis of a third independent experiment is shown in fig. S11. (E and F) Composite images of transverse petiole sections of gGLR3.3-mVenus and gGLR3.6-mVenus translational reporters expressed in cognate mutant backgrounds showing mVenus fluorescence in green and lignin autofluorescence in magenta. Refer to fig. S11 for individual fluorescence channels and analysis of an independent complementation line.

An MscS homolog from Corynebacterium glutamicum functions as a mechanosensitive glutamate efflux channel (36, 37). One hypothesis could thus be that MSL mediates glutamate efflux from cells adjacent to those that express GLRs. Because MSL10 has an anion preference, we tested whether MSL10 may conduct anionic glutamate. However, multiple patches from MSL10-expressing Xenopus oocytes failed to show tension-gated currents when provided with glutamate (fig. S12). Thus, MSL10 does not appear to be responsible for glutamate release but acts in a different manner.

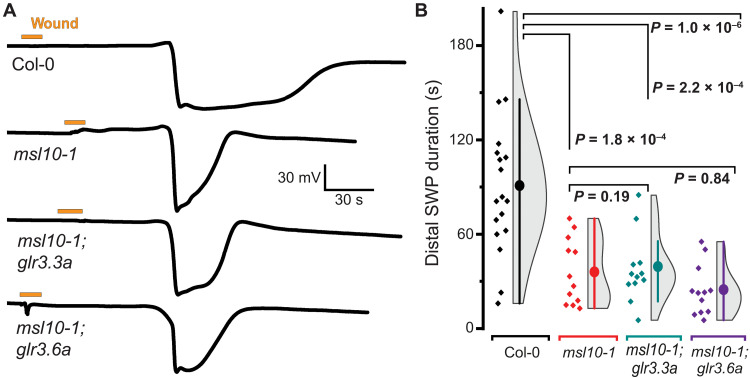

The msl10, glr3.1, glr3.3, and glr3.6 single mutants all have a similar phenotype, in which component IV is missing in the systemic SWP, while glr3.3;3.6 double mutants completely lack detectable SWPs in L13. Because both msl10;glr3.3 and msl10;glr3.6 double mutants retained the ability to produce SWPs (albeit missing component IV) that were indistinguishable from the single mutants (Fig. 6), we surmise that MSL10 acts in both GLR3.3 and GLR3.6 branches (Fig. 1A). The MSL10 expression pattern throughout the vasculature of the petiole is consistent with this interpretation (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S11).

Fig. 6. Genetic interaction of MSL10 and GLR3.3 and GLR3.6.

(A) Example recordings of L13 SWPs in Col-0, msl10-1, msl10-1;glr3.3a, and msl10-1;glr3.6 genotypes after L8 wounding (orange bar; violin plots and statistics as in Fig. 1). (B) Quantification of SWP duration in Col-0, msl10-1, msl10-1;glr3.3a, and msl10-1;glr3.6 (median ± SEM: Col-0: 95.0 ± 10.5; msl10-1: 36.1 ± 6.1 s; msl10-1;glr3.3a: 35.7 ± 5.1 s; msl10-1;glr3.6a: 24.3 ± 4.5 s). Displayed P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test (n = 12 to 17).

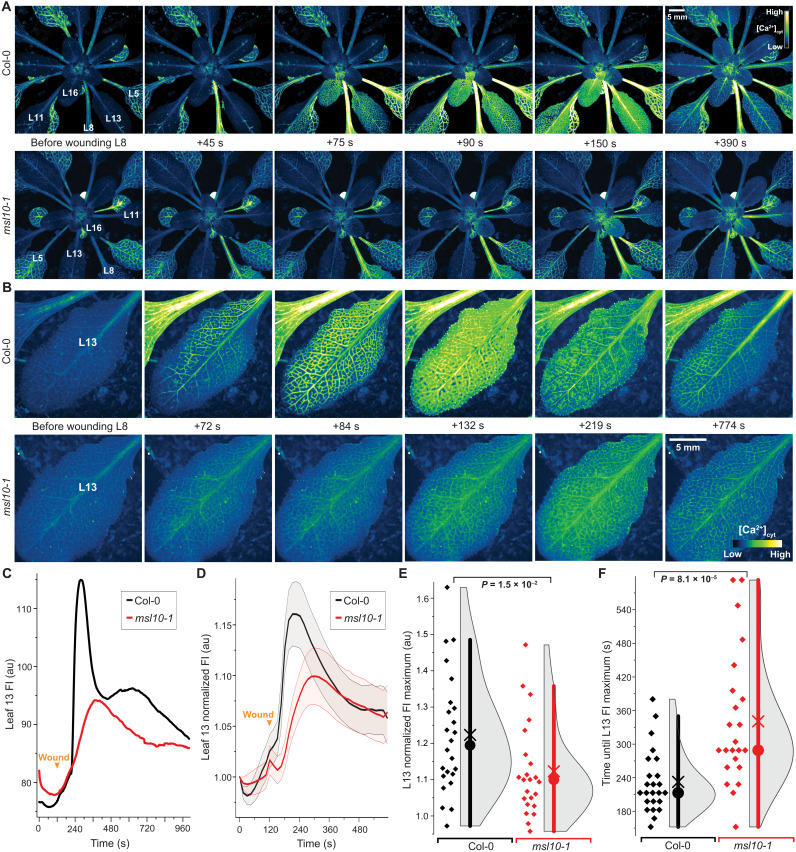

In agreement with the role of GLR3s in Ca2+ conductance, Ca2+ signaling was severely impaired in the glr3.3 and glr3.6 mutants (35). Because GLRs conduct Ca2+, while MSL10 has a preference for anions, one may predict that if MSL10 functions upstream of the GLR3s, the Ca2+ elevation caused by distal wounding would be impaired in msl10 mutants, whereas it would be unaffected if MSL10 acted downstream of the GLR3s (22, 38, 39). To test these hypotheses, the Ca2+ sensor MatryoshCaMP6s was introduced into msl10-1 and used to quantify the properties of the Ca2+ wave induced by L8 wounding. Both amplitude and kinetics of the Ca2+ wave were significantly reduced in msl10, similar to those previously described for glr3 mutants (Fig. 7, fig. S13, and movies S1 to S6) (40). Kymograph analysis indicates specific defects in the lateral spread of the calcium wave from the veins in msl10 (fig. S13).

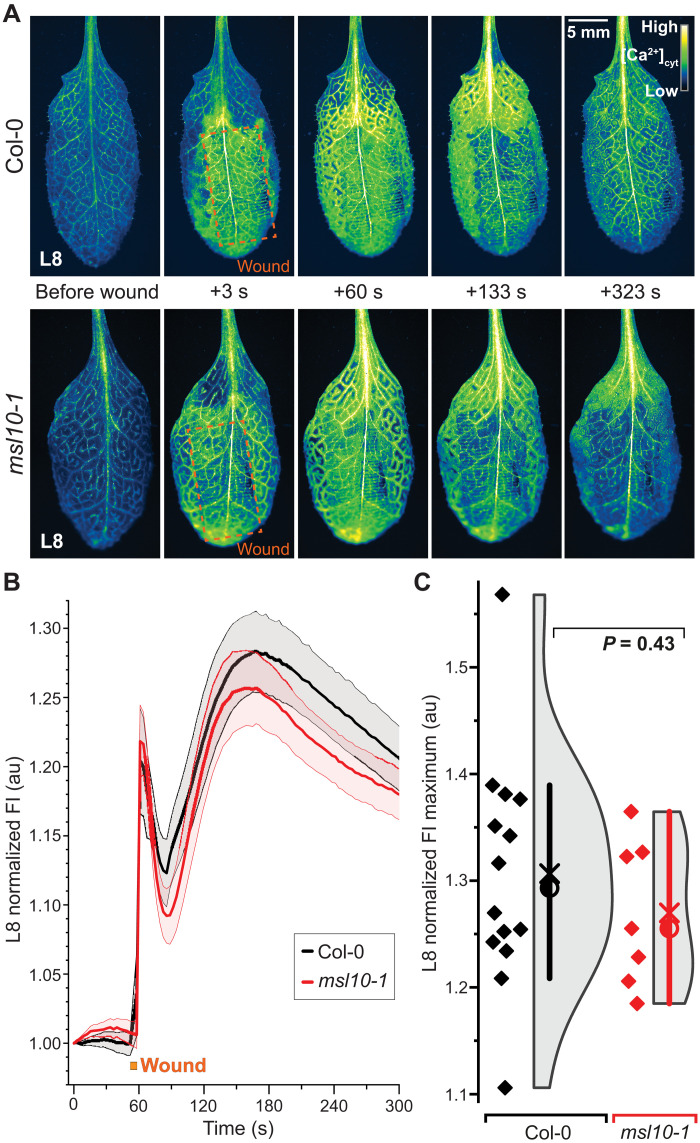

Fig. 7. Quantitative imaging of wound-induced cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]cyt) dynamics in adult plants using MatryoshCaMP6s.

(A) Whole-plant imaging reveals preferential spread of cytosolic calcium elevations to neighboring parastichous leaves upon wounding L8. Calcium elevations in leaves parastichous to L8 are attenuated in msl10-1 mutant background. (B) Close-ups of L13 calcium imaging in Col-0 and msl10-1 plants. (C) Time course quantification of data shown in (B), showing raw fluorescence intensity (FI) in arbitrary units (au). (D) Averaged FI, normalized to initial time point (FIt/FI0), observed in L13 of Col-0 and msl10-1 plants (n = 23 to 24; error bands, SEM). (E and F) Quantification and statistical analyses of L13 normalized FI maxima and time until maxima after wounding. Bar, 1.5× interquartile range; circle, median; ×, mean. Displayed P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test (n = 23 to 24). For more detailed spatiotemporal information, refer to fig. S13 and movies S1 to S4.

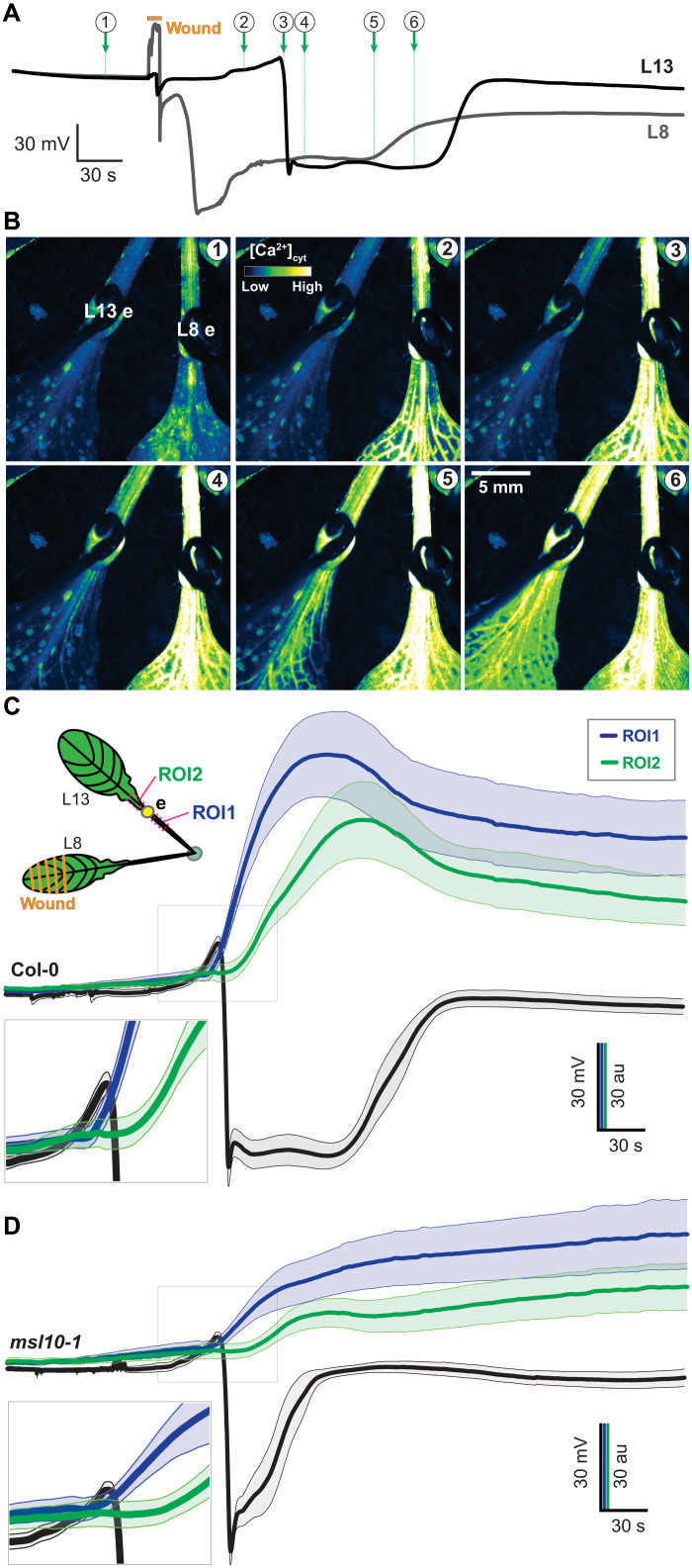

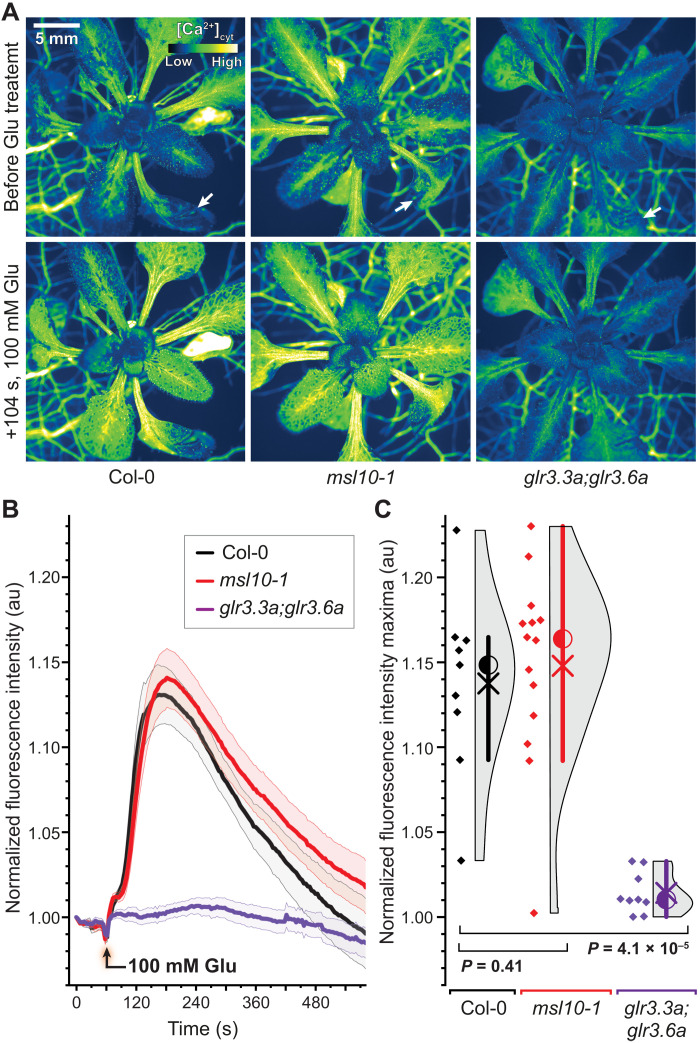

To evaluate whether the electrical signal precedes the Ca2+ wave, simultaneous recordings of electrical and Ca2+ waves were conducted. The initial hyperpolarization preceded the first detectable Ca2+ increase in L13 of Col-0 and msl10-1 plants (Fig. 8). Despite the reduction of the systemic Ca2+ response in L13 of msl10, the wound-induced Ca2+ elevations in L8 were not significantly different from those found in Col-0 (Fig. 9). By contrast, SWPs in L8 were impaired in glr3 mutants, indicating that MSL10 is not necessary for local Ca2+ responses at the wounding site but for proper SWP formation in the distal leaf. Glutamate is widely used to trigger GLR3-dependent Ca2+ waves (2). Notably, when glutamate is added externally at high concentrations, calcium responses are elicited not only in the parastichous leaves but in all leaves (Fig. 10). This observation is consistent with the absence of significant effects in msl10 in L8 (Figs. 9 and 10 and fig. S14).

Fig. 8. Simultaneous recordings of wound-induced SWP and calcium elevations in response to wounding of L8.

(A) Example L8 and L13 simultaneous surface potential recordings of a Col-0-background plant expressing MatryoshCaMP6s. Circled numbers indicate time points for images shown in (B). (B) Images from time points marked in (A) shown in pseudo-color Lookup table (LUT). (C and D) Averaged time course of L13 SP and ROI fluorescence. Error bands: SEM (n = 7 to 9). Gray boxes indicate close-ups.

Fig. 9. Wound-induced calcium elevations in L8 measured by MatryoshCaMP6s.

(A) Pseudo-color images of indicated time points before and after wounding L8 of Col-0 and msl10-1 plants expressing MatryoshCaMP6s. Wounded site is marked by orange box. (B) Averaged whole-L8 responses normalized to initial FI (FIt/FI0) (error bands, SEM; n = 7 to 14). (C) Quantification and statistical analysis of maximal FI from individual traces shown in (B). Circle, median; ×, mean. Violin plots and statistics as in Fig. 1. Displayed P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test (n = 7 to 14). See movies S5 and S6.

Fig. 10. Externally supplied glutamate triggers calcium responses in distal leaves of Col-0 and msl10-1 mutants but not in glr3.3;3.6 double mutants.

(A) Calcium elevations triggered in L13 by application of 100 mM glutamate (Glu) to L8 at the indicated cut sites (white arrows). Col-0 and msl10-1 showed similar calcium elevations in response to Glu treatment, whereas glr3.3;3.6 double mutants showed no detectable response. (B) Averaged FI responses upon treatment with 100 mM Glu normalized to initial FI (FIt/FI0; n = 9 to 14). (C) Quantification and statistical analysis of maximal FI in L13. Violin plots and statistics as in Fig. 1 (n = 9 to 14). Corresponding data for mock-treated leaves are shown in fig. S14.

On the basis of (i) the mechanosensitivity of MSL10, (ii) the similarity of the SWP phenotype in the single and double msl10/glr3.x mutants, (iii) the overlapping tissue specificity of GLR3.3 and GLR3.6 with MSL10, and (iv) the reduced Ca2+ response in the msl10 mutant (L8 lack of phenotype and excess glutamate able to trigger Ca2+ responses), we propose a model in which a mechanical signal triggers anion efflux through MSL10. The resulting depolarization is necessary for full activation of GLRs in response to wounding, but not when excess glutamate is supplied, resulting in GLR-mediated Ca2+ influx. Component IV is fully dependent on both GLR branches (Fig. 1), while components I to III can still be activated when MSL10 activity is lacking in the mutant. It is noteworthy that the MSL-GLR interaction shows similarities with the coincidence activation of mammalian glutamate receptors. At resting conditions, NMDA receptors are subject to a voltage-dependent Mg2+ block that can be released by AMPA receptor–mediated membrane depolarization. Combined depolarization and ligand activation allow Ca2+ to enter the cell via the NMDA receptor (17). One may speculate that MSL10 fulfills a similar function in GLR3 activation (41, 42).

DISCUSSION

Taken all pieces of evidence together, we propose a model (fig. S15) in which wounding triggers (i) the release of glutamate into the apoplasm by yet unidentified mechanisms, in turn activating Ca2+-permeable GLR3s. In parallel, (ii) changes in turgor pressure affect membrane tension and activate MSL10, causing anion efflux and reducing the magnitude of the TM voltage potential. Membrane depolarization promotes full activity of the GLRs, similar to the coincidence model of NMDA receptor activation. Here, depolarization triggered by mechano-stimulation of MSL10 seems necessary for GLR3 activation, which is required from component IV of the SWP and maximal Ca2+ influx. At present, GLR channel properties are not fully understood, in part, due to the effect of heterotetramerization, which is important for NMDA receptor function (17). Our model could be tested by careful electrophysiological characterization of GLR oligomers under physiological conditions and evaluation of Mg2+ dependence of GLR gating using physiological concentrations of the agonist. Our model does not explain why components I to III require two different GLR3s with different cell specificities or why MSL10 is not required for these SWP components. Notably, an MSL homolog from Venus flytrap and Cape sundew named Flycatcher1 was recently identified in trigger hairs and touch sensing cells, opening the possibility that MSLs play important roles in other mechanosensing processes (43).

In plants, pressure-assisted translocation of elicitor compounds has been proposed as a possible mechanism for SWP generation (44, 45). Glutamate appears to accumulate apoplasmically at wound sites (2). This study demonstrated that the mechanosensitive ion channel MSL10, present in plant vascular bundles, is required for component IV of wound-elicited electrical signals in distal leaves, as well as the amplitude and kinetics of the systemic Ca2+ wave. MSL10 links mechano-sensing, ion fluxes, membrane depolarization, and propagation of electrical signals, possibly supporting hypotheses regarding a long-posited role for mechanical forces in long-distance wound signaling. This convergence is in line with both Farmer’s squeeze cell and Malone’s hydraulic dispersal hypotheses (15). Coincidence signaling may help plants, with their much larger intercellular spaces and much higher ambient glutamate levels, to make use of amino acids as signals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials and growth conditions

For all surface potential recordings and sectioned samples for imaging, individually potted Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown in soil under short day conditions (8 hours light/16 hours dark or 10 hours light/14 hours dark) at a light intensity of approximately 180 μmol m−2 s−1 at 23°C and 70% humidity during the day and at 18°C and 55% humidity at night. Five- to 6-week-old plants were used for electrophysiological experiments and microscopy.

Genotyping of candidate mutants

To genotype each tested mutant (table S1), leaf tissue was collected and ground with a Qiagen TissueLyser II instrument using a 24-sample plate adapter. DNA was extracted from ground tissue using Edwards buffer (47), precipitated using ice-cold isopropanol, and pelleted by centrifugation. The sediment was washed with 70% ethanol and centrifuged. DNA was resuspended with 100 μl of water for each sample. Extracted DNA was used for PCR using the EmeraldGreen PCR Mix (Takara) and primers designed online (http://signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html). PCR was performed with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and a final extension step of 60 s at 72°C. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Primer sequences are listed in table S6. Because dorn1-2 was derived from an ethylmethane sulfonate screen, it was validated by DNA sequencing, using the primers listed in table S6. Sanger sequencing of the msl10-2 genotyping amplicon revealed that the T-DNA insertion was in exon 1 [base pair (bp) 596 after start codon]. RNA was extracted from pooled msl10-1, msl10-2, or Col-0 leaves (n = 4; two leaves from different plants per sample) using the NucleoSpin RNA Plant Kit (Macherey-Nagel Co.). Per sample, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). UBC21 (AT5G25760) was used as a control for comparison of relative transcript abundance. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was diluted 1:10 in deoxyribonuclease (DNase)–free water and used for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using the SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit (Bioline). The same procedure was used to perform qPCR on GLR3.1, GLR3.3, and GLR3.6 in msl10 mutant backgrounds. Reactions were performed with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min and then run for 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 10 s, and a final step at 72°C for 5 s.

Genome sequencing

Because SALK T-DNA lines often contain multiple T-DNA insertions, we performed genome sequencing of Col-0 wild type (WT), the msl10-1 single mutant, and the mslΔ5 quintuple mutant to identify all T-DNA insertions present in the mutant backgrounds. Arabidopsis genome sequencing was performed at the Washington University Genome Technology Assistance Center (https://gtac.wustl.edu) on an Illumina HiSeq3000 using multiplexing and 150-bp paired-end reads. Plant growth and DNA extractions followed previously published methods (48). Sequencing reads were adapter-trimmed and quality cutoff (QC)–filtered using SeqPurge (v. 2019_03-5-g57826af) (49). Reads were mapped to the pBIN19 plasmid using the bwa mem function (v. 0.7.17), applying the default parameters except -k40, -w 2, -a, and -Y. Reads were sorted by readname using the sort -n function in the SAMtools software package (v. 1.3.1) (50). Reads mapping uniquely (-q 20) to pBIN19 were extracted using SAMtools fastq and mapped against the Arabidopsis Col-0 TAIR10 genome using the bwa mem function with the parameters -a and -Y. Reads were filtered for uniquely mapping reads with QC set to -q 20. Reads overlapping with both pBIN19 and TAIR10 were extracted using a custom script and manually inspected. To verify potential T-DNA insertion sites, a second approach, using double-singleton mate-pair reads, was applied. Trimmed and QC-filtered reads were mapped to either TAIR10 or pBIN19 and filtered for uniquely mapping reads as described above. Reads were then filtered for singletons using SAMtools with parameters set to -f 8 -F 4. Read IDs of singleton reads were extracted and merged to detect overlaps. Singletons where one read mapped to TAIR10 and the mated read mapped to pBIN19 were extracted using the SeqKit software package (51).

Genetic crosses

Previously genotyped and flowering msl10-1, glr3.3, and glr3.6 mutants were crossed to generate higher-order genetic mutants. Briefly, msl10-1 flowers were vivisected, and sepals, petals, and stamens were removed. Mature stamens bearing pollen were then isolated from glr3.3 and glr3.6 flowers and dabbed onto msl10-1 stigmas. F1 plants were genotyped for mutant alleles and selfed. Subsequent generations were genotyped for homozygosity and selected for propagation accordingly. F3 msl10-1; glr3.3 and msl10-1; glr3.6 crosses were regenotyped after experimentation.

Flowering Col-0 expressing MatryoshCaMP6s were similarly crossed into msl10-1 as described above (40). Progeny were selected by root fluorescence intensity using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon). After emergence of adult leaves, plants were genotyped for msl10-1 allele presence. F2 offspring were genotyped for homozygous WT and msl10-1 alleles, and selected individuals were selfed for progeny.

Wounding assays and surface potential recordings

Surface potentials were recorded as described in published protocols. Briefly, 5- to 6-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in soil in 4-inch pots were removed from growth chambers and acclimated for a minimum of 1 hour in the recording room under 150 μmol m2 s−1 lighting at ~22°C. Electrodes were made of 0.5- or 1-mm-diameter silver wire segments (≥99.9% purity; World Precision Instruments) that were chloridized by placing the tips in either a 1 M potassium chloride (KCl) solution with electrical current supplied by a 9-V battery for 30 to 60 s or a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min. Electrodes were stripped using emery paper and/or 25% ammonium hydroxide solution and rechloridized after ~12 recordings. Individually potted plants were placed in a Faraday cage under approximately 150 μmol m−2 s−1 lighting, and an Ag-AgCl reference electrode was either inserted approximately 3 cm deep into the soil or placed in an external bath solution of full-strength Hoagland’s solution using an agar-salt bridge consisting of 2% (w/v) agar (Sigma-Aldrich, A9799) and 3 M KCl saturated with AgCl. Approximately 10- to 20-μl droplets of agarose (0.5 to 0.8% w/v) containing 10 or 50 mM KCl were pipetted onto petioles of the indicated leaves. Contacts between recording electrodes and petioles were made using the agarose droplets. Wounding was performed by crushing the apical 50% of L8 in under 10 s using a pair of modified forceps with regularly spaced rectangular plastic ridges, a modified metal hemostat (0.8-mm-deep, 1-mm-wide ridges with 0.7-mm spacing), or unmodified pliers. Surface potentials were recorded for at least 60 s before wounding, and recordings typically extended for 8 min after wounding using two dual-channel amplifiers (NPI Instruments EXT-02F amplifiers, World Precision Instruments LabTrax data acquisition digital converter, iWorx LabScribe 4 data acquisition software). Gain was set to 10 (minimal value) for all experiments, and offset was manually adjusted to zero after mounting electrodes. For each of the quantitative electrophysiology experiments presented, the experimenter was blind to sample genotype during experimentation to avoid possible biases during wounding or recording. Experimental sample sizes and results are summarized in table S5. The candidate mutant screen was performed in an unblinded manner.

Statistical analysis and data representation of surface potentials

The analysis of the SWPs was performed in an unbiased fashion using custom code written in LabView (National Instruments, 2020). Briefly, baseline for each recording was set as the immediate value succeeding end of wounding L8. Then, the first-order derivative, with appropriate filters, was used to identify minima of the first-order value during depolarization (i.e., maximum rate of depolarization). The true minimum for each trace was found in the vicinity of this point, within 20 s. SWP duration was calculated as the elapsed time between half-minimal de- and repolarization values per trace, with filters to account for aberrant data points. For visualization purposes, the traces have been shifted to zero baseline on the y axis and to the steepest depolarization slope position on the x axis.

Kernel density estimates (KDEs) were generated in OriginPro 2020 (OriginLab Corporation, 2020) using Scott’s rule to estimate bandwidth, and bandwidths were restricted to range between observed minima and maxima per genotype and dataset (e.g., to avoid subzero KDEs for SWP durations). Interquartile range was calculated in OriginPro 2020 for each dataset and graphed with KDE plots. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used to test significance between experimental variables due to occasional nonnormal distribution of data. Occasionally, L8 data included apparent artifacts in the form of stepwise, near-instantaneous voltage changes greater than 100 mV ms−1, with magnitudes sometimes exceeding 1 V, which were coincident with and likely caused by temporary disruption of the plant-surface electrode due to physical jarring during wounding. To facilitate representation of the mean and SEM of L8 data and remove aberrant data points, a percentile filter was applied in OriginPro 2020 with the window set to 300 points (3 s at 100 Hz) and percentile set to 50. Likewise, for some L13 individual recording representations, we applied a median filter with percentile set to 50 and with a minimal window of 3 points (300 ms at 10 Hz) in OriginPro 2020. Nonparametric statistics have been presented due to the apparent nonnormal distribution of extracted SWP parameters. For comparison, results of unequal Student’s t test of the same data have been provided in table S3.

Quantitative comparison of mutant and WT response curves

We hypothesized that the differences between the mutant and WT response curves might be traced to a single component missing in the mutant. As we have no a priori information on the shape of this component, we chose to model it as a single gamma distribution function; this very general, unimodal distribution function can assume shapes between exponential decay and a bell shape depending on a shape parameter k.

We first aligned representative mutant and WT response curves with respect to the major depolarization event (the global minimum of each curve). To describe the typical response curve of mutants, we averaged over the individual mutant curves at each time point. For comparison, we only considered time points after the major depolarization. We then performed a least-square fit to the mean of the WT data, W(t), fitting a weighted combination of (i) the empirical mutant response curve, M(t); (ii) a gamma distribution function Γ(k, θ; t − t0) with shape parameter k, scale parameter θ, and location shift t0; and (iii) a constant shift

with fitting parameters a, b, c, k, θ, and t0. The root mean square error (RMSE) of the fit is 0.864; the normalized RMSE (i.e., the ratio of RMSE to the range of the data) is 1.9%.

qPCR of JAZ10

For all JAZ10 transcript abundance–related experiments (n = 5 experiments; n = 3 to 4 plants per genotype), L13 was excised from msl10-1, msl10-2, or Col-0 plants 60 min following application of L8 with either mock treatment (a gentle brush with forceps) or wounding (crushing by forceps). RNA was extracted from leaves using the NucleoSpin RNA Plant Kit (Macherey-Nagel Co.), and per sample, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). For all experiments, UBC21 (At5g25760) was used as a control for comparison of relative transcript abundance, whereas target gene was JAZ10 (At5g13220; see primer sequences in table S6). cDNA was diluted 1:10 in DNase-free water and used for qPCR using the SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit (Bioline). Reactions were performed with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min and then run for 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 10 s, and a final step at 72°C for 5 s. For data visualization, all data points were normalized to the mean unwounded genotype-specific ∆Ct value.

Complementation construct and translational reporter design

To generate a translational reporter, a 2.7-kb fully encoding genomic fragment of MSL10 (gMSL10) was cloned via PCR (PrimerStar Max; Takara) from previously extracted genomic DNA from Col-0. A 720-bp fragment encoding mEGFP was subsequently cloned in-frame with a 135-bp terminator from sequence of MSL10 via PCR. The binary vector pBIN30 was linearized via “inside-out” PCR (PrimerStar Max; Takara) for later blunt end ligation with the cloned fragments. pMSL10 and gMSL10 fragments were fused to the mEGFP-terminator sequence via a flexible GLY-GLY-SER-GLY linker. The construct was ligated into the pBIN30 binary vector with In-Fusion ligation technology (Takara). The full sequence of the complementation/reporter construct has been submitted to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank (accession code MZ380291). Successful Agrobacterium-mediated transgenesis of msl10-1 plants harboring the complementation construct was evaluated by BASTA resistance and GFP fluorescence in roots.

Microscopy and sample preparation of petioles

For GFP localization experiments, both live and fixed tissues were imaged. In either case, petioles were harvested and sectioned transversely (300 μm thick) by a vibratome (Vibratome 1500, The Vibratome Company). The transcriptional reporter line for MSL10 (pMSL10:GUS-GFP) was taken from another study (18). For imaging of fresh tissue, sections were immediately placed in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.2)] on a 60 mm–by–60 mm, 0.17-mm-thick cover glass and covered with another 20 mm–by–20 mm, 0.17-mm-thick cover glass. Samples were imaged immediately after sectioning.

For imaging of live sections, vibratome-prepped samples were imaged with a Leica 20× glycerin-immersion objective [0.75 numerical aperture (NA), Plan Apo] on a TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica) with Leica LAS X software. GFP was excited with a white light laser at 488 nm, and fluorescence emissions were collected between 500 and 550 nm on a HyD SMD hybrid detector with fluorescence lifetime gate set to 0.8 to 6 ns to reduce chlorophyll autofluorescence. Lignin was excited with a 405-nm diode laser, and autofluorescence emissions were collected between 410 and 450 nm with a HyD SMD hybrid detector (Leica). Using previously published transgenic plant lines, petiole cross sections expressing mVenus fused to GLR3.3 or GLR3.6 constructs (35) were excited with a white light laser at 514 nm, and fluorescence emissions were collected between 525 and 565 nm on a HyD SMD hybrid detector with fluorescence lifetime gate set to 0.8 to 6 ns to reduce chlorophyll autofluorescence. Microscopy data were prepared for display using Fiji and were chosen as representatives of 10 to 15 acquisitions per experiment.

Calcium imaging

Progeny of genetic crosses between a line stably expressing MatryoshCaMP6s and the msl10-1 mutant line were used. Two lines each that were homozygous for msl10-1 mutation were compared to sister lines free of insertion in the MSL10 locus. Quantitative imaging was performed using a Zeiss AxioZoom.V16 zoom microscope equipped with a metal halide illuminator (HXP 200C, Zeiss), 1× objective lens (PlanNeoFluar Z 1×/0.25 NA, FWD 56 mm, Zeiss), and a Hamamatsu ORCA Flash4.0 CMOS camera. Zoom magnification was set to ×7 to ×10, and pixel binning was set to 2 × 2 or 4 × 4 pixel binning for some acquisitions. For GFP acquisition, a 488/10-nm excitation filter was used with a 491-long-pass dichroic and 519/26-nm emission filter. A motorized xy stage (Zeiss) was used to perform time-lapse tiling acquisitions. Whole-plant acquisitions were performed using 3 × 3 tiling; whole-leaf imaging was performed using 2 × 1 tiling. Tiles were stitched using ZEN Blue 2.6 (Zeiss). Images were stabilized by alignment to a stable reference slice in the stack using the “affine transformation” option Fiji or using Zen BLUE 2.6. A pair of pliers was used to wound L8. Manual oval regions of interest (ROIs) were used for quantitative analysis. Simultaneous calcium imaging and surface potential recordings were performed using the same equipment and settings described in separate sections. Kymograph ROIs were drawn using a 698-μm transect line with a 10-pixel spline straddling a secondary vein, and kymographs were generated via the KymographBuilder plugin in Fiji (ImageJ). Images and movie are displayed using the Green Fire Blue lookup table in Fiji (52).

Application of l-glutamic acid to cut leaves during calcium imaging was performed using 2.5- to 3-week-old Arabidopsis plants expressing MatryoshCaMP6s. Plants were grown in 6-cm-diameter petri dishes containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with vitamins and MES (Duchefa) supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose (1/2 MS) and 1% (w/v) agar. Before experiments, leaves were counted in order of appearance. A small incision was made in L1 of each plant using scissors, and plants were acclimated for ≥10 min before imaging. Images were acquired for 60 s before treatment with 100 mM l-glutamic acid dissolved in 1/2 MS with 0.25% Silwet L-77 (pH 5.8) or control lacking glutamate. The solution (10 μl) was directly pipetted onto the cut surface of L1 after acclimation period.

For the analysis of l-glutamic acid–elicited MatryoshCaMP6s responses, whole field-of-view ROIs were used to measure average fluorescence intensity of the EGFP channel of MatryoshCaMP6s. Average intensity values were normalized to time point 0. Normalized values were averaged, and SEM values were calculated using OriginPro 2021.

Analysis of wound-induced calcium elevations in L8 was performed by first applying a Gaussian blur filter (default, 2) to all images. To remove background fluorescence from the image, a binary mask (Method: Triangle) was generated. Image fluorescence values of the binary mask were multiplied by values of the Gaussian blur-filtered image and divided by the binary mask to create a masked image stack for calculation of mean fluorescence intensity values. The whole field of view was selected as ROI for measurements of mean fluorescence intensities.

Electrophysiological characterization in Xenopus oocytes

Oocyte preparation and imaging of oocytes were performed as described (22). All the traces were obtained from excised inside-out patches from oocytes expressing pOO2-MSL10-GFP (22). Bath buffer was ND96 [96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)]. Pipette buffer was NaG [98 mM sodium glutamate, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)]. Application and monitoring of pressure ramps, voltage, and data acquisition were performed as described in (53).

Phylogenetic analyses

The origin of the 39 members of the MscS superfamily included in the phylogenetic analyses and their UniProt or NCBI accession numbers are as follows: MscS (E. coli, P0C0S1), MscK (E. coli, P77338), MscM (E. coli, P39285), MSL1 (A. thaliana, Q8VZL4), MSL2 (A. thaliana, Q56X46), MSL3 (A. thaliana, Q8L7W1), MSL4 (A. thaliana, Q9LPG3), MSL5 (A. thaliana, Q9LH74), MSL6 (A. thaliana, Q9SYM1), MSL7 (A. thaliana, F4IME1), MSL8 (A. thaliana, F4IME2), MSL9 (A. thaliana, Q94M97), MSL10 (A. thaliana, Q9LYG9), Msy1 (S. pombe, O74839), Msy2 (S. pombe, O14050), MscMJ (Methanococcus jannaschii, Q57634), MscOL (Ostreococcus lucimarinus, ABP00956), MscCR1 (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, BAF48401), MscCR2 (C. reinhardtii, XP_001690099), MscCR3 (C. reinhardtii, XP_001689635), MscAN (Aspergillus nidulans, XP_680840), MscCP (Coccidioides posadasii, EER23643), MscNC (Neurospora crassa, XP_961167), MscTM (Talaromyces marneffei, XP_002149714), MscPT (Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, XP_001938146), MscTMe (Tuber melanosporum, XP_002840873), MscCN (Cryptococcus neoformans, XP_776457), MscLB (Laccaria bicolor, XP_001877365), and MscUM (Ustilago maydis, KIS68709).

Results of the phylogenetic analysis are displayed as an unrooted tree generated using the NGPhylogeny tool (54) and rendered with the help of iTOL (55). The full-length protein sequences were aligned using the MAFFT (56) alignment algorithm with a gap-opening penalty of 1.53 and a gap-extension penalty of 0.123. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method with the LG amino acid replacement matrix. Clade confidence scores were generated via bootstrapping (n = 1000 replicates, red values presented as percentage), and clades with bootstrap values of less than 50% were collapsed.

To determine the similarity between the sequences of members of the MSL family and the sequences of other MscS, the sequences of MscK (E. coli), MscM (E. coli), MSL1-10 (A. thaliana), Msy1 and Msy2 (S. pombe), YbdG (E. coli), YbiO (E. coli), and YnaI (E. coli) were subjected to a multiple sequence alignment using the MAFFT server (56) and the L-INS-i algorithm (57). To improve accuracy, the alignment was enriched with homologs identified with the MAFFT-homologs option (600 homologs, E-value threshold of 0.1). The resulting alignment was used to calculate sequence similarity and sequence identity matrices with the Bio3D package (58, 59) in R.

To assess the similarity between the EF-hand motifs in EF-MscS (34) and the EF-hand–derived motif in MSL10, a multiple sequence alignment of the EF-MscS sequences listed in the supplementary information to (34) and the sequence of MSL10 (UniProt ID: Q9LYG9) was generated with the MAFFT server (56) using the L-INS-i algorithm (57). Putative EF-hand regions were identified with the ScanProsite tool (60) by searching all sequences against the motif definitions stored in the PROSITE database (61) and the motif definitions for pseudo-EF motifs and EF-hand–like motifs included in (62).

Generation of the MSL10 structural model

To generate a multimeric structure of MSL10, homology models of regions 430 to 516 and 508 to 732 were generated with SWISS-MODEL (63), using as templates the EF-motif of human calcyphosin [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 3E3R] and the YnaI mechanosensitive channel of E. coli (PDB ID: 5Y4O), respectively. As no template was found for the N-terminal TM region of MSL10, it was predicted ab initio. Residue-residue contacts were predicted by RaptorX (fig. S5C) (64). The contacts for the region 167 to 562, together with secondary structure predictions from the SCRATCH suite (65), were used to generate models with CONFOLD2 (66). The homology models and ab initio structure from the largest CONFOLD2 cluster were combined using MODELLER (67), imposing symmetry restraints and using the multimeric YnaI-homologous region as the assembly framework, keeping the YnaI-homologous region as in the original model. The composite model was oriented in the membrane according to MEMEMBED (68), using the YnaI TM region to guide the model orientation. The oriented structure was refined with Rosetta 3.12 using the fastrelax protocol and the MP (membrane protein) framework (69), generating 20 alternative structures. The best scoring model using the franklin2019 scoring function for membrane proteins and the POPC (palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine) implicit parameters (70) was selected. Residues potentially involved in Ca2+ binding in the calcyphosin homology region were identified with IonCom (64).

To evaluate the agreement between the refined model, including the region derived by homology modeling, and the predicted contacts, a distance violation score (DV) was computed according to Eq. 1

| (1) |

where L is the model length, dij is the distance between Cβ atoms of the corresponding residue pair of the model (Cα if a glycine is used), and P is the RaptorX prediction confidence bounded between 0 and 1 (Fig. 4C), yielding a value of DV = 5.31. According to the results of an equivalent score (71), this indicates that the structural model has the same fold as the native structure (71).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank N. Fotouhi, Y.-Q. Gao, and S. Moussavi (University of Lausanne) for assistance with establishing the surface potential recording platform; L. Strader (Duke University) for help with genome sequencing of the msl mutants; and B. de Saint-Lazare (Languedoc) for electricity in plants.

Funding: This work was funded by grants from NSF (MCB 1413254), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC-2048/1—project ID 390686111 and SFB 1208—Project-ID 267205415, as well as the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship to W.B.F. H.G. was funded, in part, by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft {DFG, German Research Foundation [project 267205415—CRC 1208, project A03 and Research Unit 2518 DynIon, project P7 (GO 1367/2-1)]}. H.G. is grateful for computational support by the “Zentrum für Informations und Medientechnologie” at the Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf and for the computing time provided by the John von Neumann Institute for Computing (NIC) on the supercomputer JUWELS at Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC) (user IDs: HKF7 and HCN2). D.B. was supported by NSF Science and Technology Center grant 1548571 and NSF MCB 1253103 to E.S.H. The contributions by S.M. and M.J.L. were supported by a grant from Volkswagenstiftung in the “Life?” initiative (to M.J.L.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: J.M.-L., T.J.K., D.W.E., M.M.W., H.G., E.S.H., E.E.F., and W.B.F. Methodology: J.M.-L., D.W.E., M.M.W., H.G., T.J.K., and W.B.F. Investigation: J.M.-L., M.M., N.M.G., C.S.A.S., T.H., D.B., M.Be., S.N.S.-V., A.M., M.Bo., D.B., S.M., M.J.L., and T.J.K. Figure design and preparation: J.M.-L., S.M., T.J.K., and W.B.F. Writing: J.M.-L., H.G., M.J.L., M.M.W., T.J.K., and W.B.F. Supervision: D.W.E., M.M.W., H.G., T.J.K., and W.B.F.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: SWP recordings have been uploaded to the Open Science Foundation (OSF) website and are available at https://osf.io/2cwrp/?view_only=8485887331774740ac54170148a8f431. All scripts used to analyze genome sequencing data and surface potential data are available through the OSF link. The msl10-1 genome sequencing datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under project ID PRJNA735717.

Correction (23 September 2022): The authors inadvertently provided the wrong file for Movie S2. The previous version was a duplicate of Movie S5. The correct movie file for Movie S2 has now been included.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S15

Tables S1 to S6

Legends for movies S1 to S6

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S6

Data files S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Walch-Liu P., Liu L.-H., Remans T., Tester M., Forde B. G., Evidence that l-glutamate can act as an exogenous signal to modulate root growth and branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1045–1057 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toyota M., Spencer D., Sawai-Toyota S., Jiaqi W., Zhang T., Koo A. J., Howe G. A., Gilroy S., Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling. Science 361, 1112–1115 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mousavi S. A. R., Chauvin A., Pascaud F., Kellenberger S., Farmer E. E., GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature 500, 422–426 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Featherstone D. E., Shippy S. A., Regulation of synaptic transmission by ambient extracellular glutamate. Neuroscientist 14, 171–181 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohaus G., Pennewiss K., Sattelmacher B., Hussmann M., Hermann Muehling K., Is the infiltration-centrifugation technique appropriate for the isolation of apoplastic fluid? A critical evaluation with different plant species. Physiol. Plant. 111, 457–465 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilot G., Stransky H., Bushey D. F., Pratelli R., Ludewig U., Wingate V. P., Frommer W. B., Overexpression of GLUTAMINE DUMPER1 leads to hypersecretion of glutamine from hydathodes of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell 16, 1827–1840 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wudick M. M., Portes M. T., Michard E., Rosas-Santiago P., Lizzio M. A., Nunes C. O., Campos C., Damineli D. S. C., Carvalho J. C., Lima P. T., Pantoja O., Feijó J. A., CORNICHON sorting and regulation of GLR channels underlie pollen tube Ca2+ homeostasis. Science 360, 533–536 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfieri A., Doccula F. G., Pederzoli R., Grenzi M., Bonza M. C., Luoni L., Candeo A., Armada N. R., Barbiroli A., Valentini G., Schneider T. R., Bassi A., Bolognesi M., Nardini M., Costa A., The structural bases for agonist diversity in an Arabidopsis thaliana glutamate receptor-like channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 752–760 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavendra A. S., Gonugunta V. K., Christmann A., Grill E., ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 395–401 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi F., Suzuki T., Osakabe Y., Betsuyaku S., Kondo Y., Dohmae N., Fukuda H., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K., A small peptide modulates stomatal control via abscisic acid in long-distance signalling. Nature 556, 235–238 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng X., Kang S., Jing Y., Ren Z., Li L., Zhou J.-M., Berkowitz G., Shi J., Fu A., Lan W., Zhao F., Luan S., Danger-associated peptides close stomata by OST1-Independent activation of anion channels in guard cells. Plant Cell 30, 1132–1146 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilroy S., Białasek M., Suzuki N., Górecka M., Devireddy A. R., Karpiński S., Mittler R., ROS, calcium, and electric signals: Key mediators of rapid systemic signaling in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 1606–1615 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi W. G., Swanson S. J., Gilroy S., High-resolution imaging of Ca2+, redox status, ROS and pH using GFP biosensors. Plant J. 70, 118–128 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer E. E., Gao Y.-Q., Lenzoni G., Wolfender J.-L., Wu Q., Wound- and mechanostimulated electrical signals control hormone responses. New Phytol. 227, 1037–1050 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmer E. E., Gasperini D., Acosta I. F., The squeeze cell hypothesis for the activation of jasmonate synthesis in response to wounding. New Phytol. 204, 282–288 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malone M., Rapid, long-distance signal transmission in higher plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 22, 163–228 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen K. B., Yi F., Perszyk R. E., Furukawa H., Wollmuth L. P., Gibb A. J., Traynelis S. F., Structure, function, and allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 1081–1105 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haswell E. S., Peyronnet R., Barbier-Brygoo H., Meyerowitz E. M., Frachisse J.-M., Two MscS homologs provide mechanosensitive channel activities in the Arabidopsis root. Curr. Biol. 18, 730–734 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousavi S. A. R., Nguyen C. T., Farmer E. E., Kellenberger S., Measuring surface potential changes on leaves. Nat. Protoc. 9, 1997–2004 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roblin G., Analysis of the variation potential induced by wounding in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 26, 455–461 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu D., Haswell E. S., The mechanosensitive ion channel MSL10 potentiates responses to cell swelling in Arabidopsis seedlings. Curr. Biol. 30, 2716–2728.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maksaev G., Haswell E. S., MscS-Like10 is a stretch-activated ion channel from Arabidopsis thaliana with a preference for anions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19015–19020 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maksaev G., Shoots J. M., Ohri S., Haswell E. S., Nonpolar residues in the presumptive pore-lining helix of mechanosensitive channel MSL10 influence channel behavior and establish a nonconducting function. Plant Direct 2, e00059 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerringue Y., Thomine S., Frachisse J.-M., Sensing and transducing forces in plants with MSL10 and DEK1 mechanosensors. FEBS Lett. 592, 1968–1979 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.E. S. Haswell, in Current Topics in Membranes, vol. 58 of Mechanosensitive Ion Channels, Part A (Academic Press, 2007), pp. 329–359. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levina N., Tötemeyer S., Stokes N. R., Louis P., Jones M. A., Booth I. R., Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: Identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 18, 1730–1737 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox C. D., Bavi N., Martinac B., Bacterial mechanosensors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 80, 71–93 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy B., Bavi N., Lu A., Park Y., Perozo E., Molecular basis of force-from-lipids gating in the mechanosensitive channel MscS. eLife 8, e50486 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Hu Y., Wang J., Liu X., Zhang W., Sun L., Structural insights into a plant mechanosensitive ion channel MSL1. Cell Rep. 30, 4518–4527.e3 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng Z., Maksaev G., Schlegel A. M., Zhang J., Rau M., Fitzpatrick J. A. J., Haswell E. S., Yuan P., Structural mechanism for gating of a eukaryotic mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Nat. Commun. 11, 3690 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu D., Shoots J. M., Haswell E. S., Interactions between the N- and C-termini of the mechanosensitive ion channel AtMSL10 are consistent with a three-step mechanism for activation. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 4020–4032 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou Y., Chintamanani S., He P., Fukushige H., Yu L., Shao M., Zhu L., Hildebrand D. F., Tang X., Zhou J.-M., A gain-of-function mutation in Msl10 triggers cell death and wound-induced hyperaccumulation of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58, 600–609 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakayama Y., Yoshimura K., Iida H., Organellar mechanosensitive channels in fission yeast regulate the hypo-osmotic shock response. Nat. Commun. 3, 1020 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malcolm H. R., Maurer J. A., The mechanosensitive channel of small conductance (MscS) superfamily: Not just mechanosensitive channels anymore. Chembiochem 13, 2037–2043 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen C. T., Kurenda A., Stolz S., Chételat A., Farmer E. E., Identification of cell populations necessary for leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling in a wounded plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10178–10183 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto K., Murata J., Konishi T., Yabe I., Nakamatsu T., Kawasaki H., Glutamate is excreted across the cytoplasmic membrane through the NCgl1221 channel of Corynebacterium glutamicum by passive diffusion. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76, 1422–1424 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura J., Hirano S., Ito H., Wachi M., Mutations of the Corynebacterium glutamicum NCgl1221 gene, encoding a mechanosensitive channel homolog, induce L-glutamic acid production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4491–4498 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi Z., Stephens N. R., Spalding E. P., Calcium entry mediated by GLR3.3, an Arabidopsis glutamate receptor with a broad agonist profile. Plant Physiol. 142, 963–971 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortiz-Ramírez C., Michard E., Simon A. A., Damineli D. S. C., Hernández-Coronado M., Becker J. D., Feijó J. A., GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE channels are essential for chemotaxis and reproduction in mosses. Nature 549, 91–95 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ast C., Foret J., Oltrogge L. M., Michele R. D., Kleist T. J., Ho C.-H., Frommer W. B., Ratiometric Matryoshka biosensors from a nested cassette of green- and orange-emitting fluorescent proteins. Nat. Commun. 8, 431 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer M. L., Westbrook G. L., Guthrie P. B., Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature 309, 261–263 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowak L., Bregestovski P., Ascher P., Herbet A., Prochiantz A., Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature 307, 462–465 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.C. Procko, S. E. Murthy, W. T. Keenan, S. A. R. Mousavi, T. Dabi, A. Coombs, E. Procko, L. Baird, A. Patapoutian, J. Chory, Stretch-activated ion channels identified in the touch-sensitive structures of carnivorous Droseraceae plants. Elife 10, e64250 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans M. J., Morris R. J., Chemical agents transported by xylem mass flow propagate variation potentials. Plant J. 91, 1029–1037 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ricca U., Transmission of stimuli in plants. Nature 117, 654–655 (1926). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari A., Chételat A., Nguyen C. T., Farmer E. E., Arabidopsis H+-ATPase AHA1 controls slow wave potential duration and wound-response jasmonate pathway activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 20226–20231 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards K., Johnstone C., Thompson C., A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1349 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enders T. A., Oh S., Yang Z., Montgomery B. L., Strader L. C., Genome sequencing of Arabidopsis abp1-5 reveals second-site mutations that may affect phenotypes. Plant Cell 27, 1820–1826 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sturm M., Schroeder C., Bauer P., SeqPurge: Highly-sensitive adapter trimming for paired-end NGS data. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 208 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen W., Le S., Li Y., Hu F., SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLOS ONE 11, e0163962 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J. Y., White D. J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., Cardona A., Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maksaev G., Haswell E. S., Expression and characterization of the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 138, 641–649 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemoine F., Correia D., Lefort V., Doppelt-Azeroual O., Mareuil F., Cohen-Boulakia S., Gascuel O., NGPhylogeny.fr: New generation phylogenetic services for non-specialists. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W260–W265 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Letunic I., Bork P., Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katoh K., Rozewicki J., Yamada K. D., MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1160–1166 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katoh K., Kuma K., Toh H., Miyata T., MAFFT version 5: Improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 511–518 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grant B. J., Rodrigues A. P. C., ElSawy K. M., McCammon J. A., Caves L. S. D., Bio3d: An R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics 22, 2695–2696 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skjærven L., Yao X.-Q., Scarabelli G., Grant B. J., Integrating protein structural dynamics and evolutionary analysis with Bio3D. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 399 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Castro E., Sigrist C. J. A., Gattiker A., Bulliard V., Langendijk-Genevaux P. S., Gasteiger E., Bairoch A., Hulo N., ScanProsite: Detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W362–W365 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sigrist C. J. A., Cerutti L., de Castro E., Langendijk-Genevaux P. S., Bulliard V., Bairoch A., Hulo N., PROSITE, a protein domain database for functional characterization and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D161–D166 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Y., Yang W., Kirberger M., Lee H.-W., Ayalasomayajula G., Yang J. J., Prediction of EF-hand calcium-binding proteins and analysis of bacterial EF-hand proteins. Proteins 65, 643–655 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F. T., de Beer T. A. P., Rempfer C., Bordoli L., Lepore R., Schwede T., SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang S., Sun S., Li Z., Zhang R., Xu J., Accurate de novo prediction of protein contact map by ultra-deep learning model. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005324 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Magnan C., Baldi P., SSpro/ACCpro 5: Almost perfect prediction of protein secondary structure and relative solvent accessibility using profiles, machine learning and structural similarity. Bioinformatics 30, 2592–2597 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adhikari B., Cheng J., CONFOLD2: Improved contact-driven ab initio protein structure modeling. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 22 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webb B., Sali A., Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 54, 5.6.1–5.6.37 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nugent T., Jones D. T., Membrane protein orientation and refinement using a knowledge-based statistical potential. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 276 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alford R. F., Leman J. K., Weitzner B. D., Duran A. M., Tilley D. C., Elazar A., Gray J. J., An integrated framework advancing membrane protein Modeling and design. PLOS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004398 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alford R. F., Fleming P. J., Fleming K. G., Gray J. J., Protein structure prediction and design in a biologically realistic implicit membrane. Biophys. J. 118, 2042–2055 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Michel M., Menéndez Hurtado D., Uziela K., Elofsson A., Large-scale structure prediction by improved contact predictions and model quality assessment. Bioinformatics 33, i23–i29 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi W. G., Toyota M., Kim S.-H., Hilleary R., Gilroy S., Salt stress-induced Ca2+ waves are associated with rapid, long-distance root-to-shoot signaling in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 6497–6502 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi J., Tanaka K., Cao Y., Qi Y., Qiu J., Liang Y., Lee S. Y., Stacey G., Identification of a plant receptor for extracellular ATP. Science 343, 290–294 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scholz S. S., Malabarba J., Reichelt M., Heyer M., Ludewig F., Mithöfer A., Evidence for GABA-induced systemic GABA accumulation in Arabidopsis upon wounding. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 388 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Krol E., Mentzel T., Chinchilla D., Boller T., Felix G., Kemmerling B., Postel S., Arents M., Jeworutzki E., Al-Rasheid K. A. S., Becker D., Hedrich R., Perception of the Arabidopsis danger signal peptide 1 involves the pattern recognition receptor AtPEPR1 and its close homologue AtPEPR2. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13471–13479 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng X., He K., Kleist T., Chen F., Luan S., Anion channel SLAH3 functions in nitrate-dependent alleviation of ammonium toxicity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 474–486 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S15

Tables S1 to S6

Legends for movies S1 to S6

References

Movies S1 to S6

Data files S1 to S3