Abstract

Objective

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the possible function of miR-130a in atherosclerosis (AS), protection against AS, and its molecular biological mechanism.

Methods

Apoe−/− mice were fed a high-fat diet as the AS mice model. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used as in vitro model. Serum samples or cells were used to measure the expression of inflammation. Serum samples or cells were used to determine MiRNA expression profiles using the edgeR tool from Bioconductor. Western Blot analysis was used to assess protein expressions of proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and nuclear factor (NF)-κB.

Results

MiRNA-130a expression was up-regulated in atherosclerotic mice. In addition, over-expression of miRNA-130a promoted inflammation factors [tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8] in the in vitro model of AS. However, down-regulation of miRNA-130a reduced inflammation (suppressed TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8) in the in vitro model. Furthermore, over-expression of miRNA-130a could also suppress the protein expression of PPARγ and induce NF-κB protein expression in the in vitro model. However, suppression of miRNA-130a induced the protein expression of PPARγ and suppressed NF-κB protein expression in the in vitro model of AS. Activation of PPARγ reduced the pro-inflammatory effects of miRNA-130a on the AS-induced in vitro model.

Conclusion

These results strongly support that miRNA-130a suppression can protect against atherosclerosis through inhibiting inflammation by regulating the PPARγ/NF-κB expression.

Keywords: microRNA-130a, atherosclerosis, inflammation, PPAR-gamma, NF-kappaB

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) can be induced by multiple factors such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and smoking (1). Currently, the inflammation theory based on lipid infiltration theory and injury response theory is extensively recognized to be the pathogenesis of AS (2). First proposed by the famous scholar Ross in 1976, this theory believes that AS is a process of pathological change in which lipid accumulates in the arterial wall to form a local plaque. It is mediated by inflammatory response accompanied by the genesis of oxidative stress (OS) (3). The interactions between the immune inflammatory cells (such as macrophages and dendritic cells) and multiple inflammatory factors play a key role in AS genesis and development, which can be ascribed to the characteristics of multiple targets and complexity of inflammatory action of cytokines (2).

AS is a chronic inflammatory disease induced by multiple factors in the vascular wall (4). Studies on the regulatory effect of miRNA during AS development are ongoing (4). Nonetheless, it is believed that miRNA expression in the vascular wall cells (endothelial and smooth muscle cells) as well as the infiltrated white blood cell subsets can affect disease development (5). Typically, the role of miRNA in regulating cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis is being gradually discovered. Moreover, abnormal miRNA expression is verified to be closely correlated with the genesis and development of multiple diseases (6). In recent years, the role of miRNA in AS has attracted increasing attention (6). Li et al. (7) have indicated that miR-130a has a role in the regulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in osteoarthritis. Yao et al. (8) have shown that the knockdown of miR-130a-3p alleviates NF-κB in spinal cord injury.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), which is a ligand-activated transcription factor, is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that can react with specific DNA response elements to regulate gene expression (9). Its main function is converting the homeostasis changes, drugs, nutrition, and inflammatory stimulations in the body into intracellular signals (10). Thus, it plays a key role as a messenger in regulating energy metabolism, cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, inflammatory response, endogenous active substance synthesis, and secretion (9). Meanwhile, PPAR can be activated by endogenous fatty acids and its metabolites and is, therefore, named the fatty acid receptor (11). PPARγ is a subtype of PPAR whose vascular and biological functions gradually starts with the discovery of PPARγ expression in mononuclear macrophages, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells (9).

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a transcription factor that can regulate multiple gene transcription functions and specifically bind with multiple specific sites in cell gene promoter or enhancer sequences (12). Therefore, it can promote gene transcription and expression and is closely related to important pathophysiological processes (13). Recent studies indicate that genes involved in the inflammatory response during atherosclerotic plaque formation are mostly the NF-κB target genes, whose transcription and expression are mainly regulated by the NF-κB/IκB signaling pathway (13). Wang et al. (14) have reported that miR-130a upregulates the mTOR pathway by NF-κB in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the mechanism and function of miR-130a in atherosclerosis and inflammation and appraised its possible molecular biological I.

Methods

Atherosclerosis animal model

The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Health and Utilization Committee of the Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. ApoE−/− mice were fed with a high-fat diet for 12 weeks similar to the AS model group in literature (15). C57BL/6 mice (WT, n=6) were fed a normal diet for 12 weeks.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

After induction model of AS, all the mice were sacrificed by decapitation after anesthetizing them with 35 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. Whole blood of all the mice was used to collect serum samples at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the serum samples were saved at −80°C to measure the expression of inflammation levels using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. T TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-18 were measured using TNF-α (H052), IL-1β (H002), IL-6 (H007) and IL-18 (H015) ELISA kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biology Engineering Institute).

Oil Red O staining

The blood vessels were collected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for one day. The aorta was embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μM sections on the vibrator. The aorta was then stained with hematoxylin and eosin for 15 minutes and measured with a Olympus microscope (Olympus optics, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and miRNA expression profiles

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent. The cDNA was reverse transcripted by Primescript Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), and real-time quantitative PCR was performed using 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biological Systems, Forster, California, USA) Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara, Dalian, China). RT-PCR was carried out as follows: Pre denaturation at 94°C for 10 minutes, denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for two minutes, 40 cycles. QRT PCR primers: miRNA-130a, 5 ′-GTCAGTGCTAAAAGGGCAT-3′ and reverse, 5 ′-CAGTGCGTGTCGTGGAGT-3′; U6 forward, 5 ′-GCTTCGGCAGCACTATAAT-3′ and reverse, 5 ′-CGCTTCACGAATTGCTGTCAT-3′. The relative gene expression was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method (16).

RNA samples were amplified by ovation PicoSL WTA System V2 Kit (NuGEN) and sureprint G3 human Ge V2, 8×60k microarray (Agilent). cDNAs was produced using superscript II reverse transcriptase (Biotechnology). Surescan microarray scanner was used for data acquisition, and feature extraction software v. 10.7.3.1 (Agilent, USA) was used to extract the signal, which was submitted to GEO (gene expression integrated system, registration number gse80754).

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro model of atherosclerosis

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). MiRNA-130a (supplemented with 10% FBS), anti-miRNA-30a (anti-miRNA-130a with 10% FBS), and negative mimics (negative mimics with 10% FBS) were transfected into HUVECs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). HUVECs were transfected with negative mimics in the negative group, with miRNA-130a mimics in the miRAN-130a group, and with anti-miRNA-130a mimics in the anti-130a group. After transfection at 37°C for six hours, the medium of all the groups was subsequently replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS for 42 hours and treated with 100 ng lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 2000 for six hours. The cell supernatant medium was collected at 2000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the level of inflammation was measured by ELISA.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

According to the bioinformatics results, the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of PPARγ was cloned into pMIR-REPORT luciferase reporter plasmids (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). PPARγ plasmids were co-transfected with miR-24 mimics into HUVECs using Lipofectamine 2000. After incubation at 37°C for 48 hours, the cells were lysed using a dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega Corporation).

Western blot analysis

According to the manufacturer’s protocol, total protein was extracted by Ripa analysis (p0013b, Beyotime) and quantified by BCA Kit (p0009, Beyotime). A total of 50 g of protein was placed on 12% sodium alkylsulfate polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was sealed in 5% skim milk for one hour at room temperature and incubated with the main antibody overnight at 4°C: PPARγ (sc-166731, 1:1000, Santa Cruz biotechnology group), NF-κB (sc-71677, 1:1000, Santa Cruz biotechnology group), and GAPDH (sc-51631, 1:5000, Santa Cruz biotechnology group). Subsequently, the membrane was washed with tris-buffered saline and Polysorbate 20 (TBST) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase bound goat anti-rabbit IgG at room temperature for one hour (sc-2004, 1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein detection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Beijing Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, China), and imaging was performed by sodium imaging laboratory 3.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence

The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 minutes and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. The cells were connected with PPARγ (Sc-166731, 1:100, Santa Cruz biotechnology company) and 0.25% Trionx-100 were incubated overnight in PBS at 4°C. The cells were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG CFL 555 (sc-362272, 1:100, Santa Cruz biotechnology company) at 37°C for two hours and stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in the dark for 15 minutes. Cells were observed using Zeiss Axioplan 2 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3) using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The data between the groups were compared by student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance and post-ho test. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

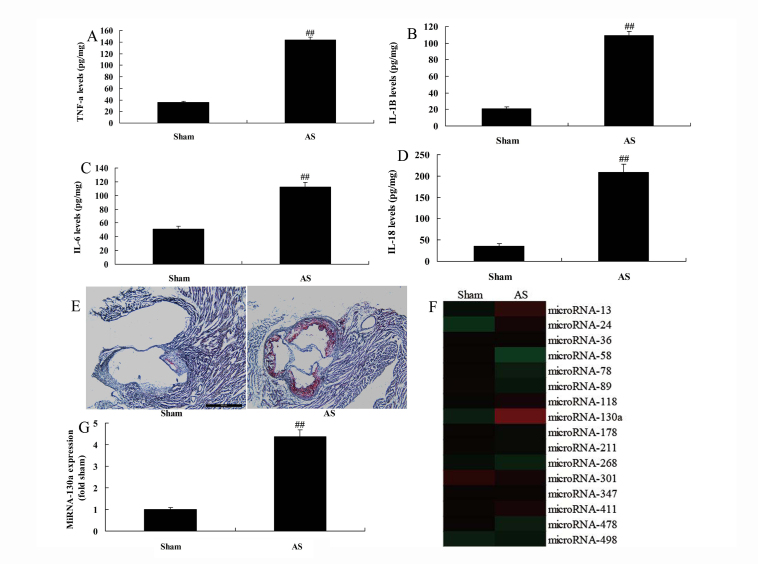

miRNA-130a serum levels expression in atherosclerotic mice

The serum expression levels of IL-18, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 were increased in the atherosclerotic mice model compared with those in the sham group (Fig. 1a–1d). Oil Red O staining suggested that the rate of thrombus in the atherosclerotic mice was higher than that in the sham group (Fig. 1e). In addition, the heat map or qPCR demonstrated that miRNA-130a expression was upregulated in atherosclerotic mice than that in the sham group (Fig. 1e–1g).

Figure 1.

Expression of miRNA-130a in atherosclerotic mice

A, B, C and D: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 levels

F and G: Oil Red O staining (×100, E), gene chip and qPCR for miRNA-130a expression. Sham group; AS, miRNA-130a group.

##P<0.01 comparison with sham control group.

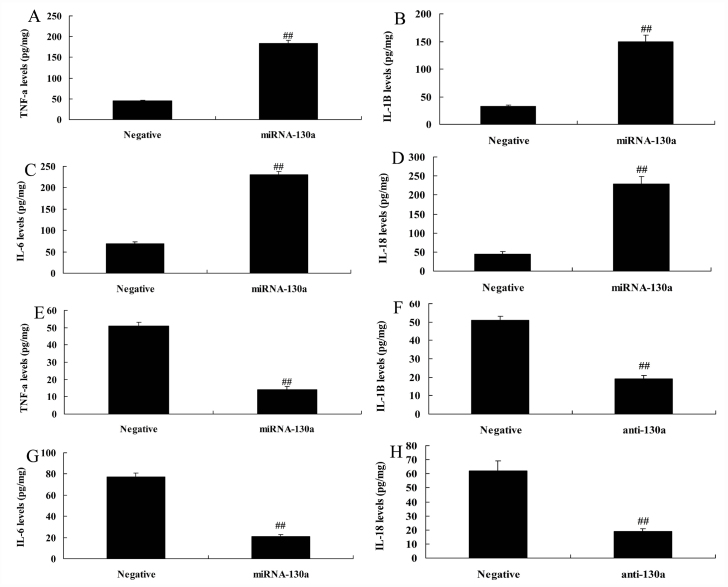

MiRNA-130a regulated inflammation in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS

MiRNA-130a over-expression was found to increase the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 in HUVECs in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS compared with those in the negative group (Fig. 2a–2d). However, down-regulation of miRNA-130a suppressed the levels of IL-18, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS compared with those in the negative group (Fig. 2e–2h).

Figure 2.

MiRNA-130a regulates inflammation in in vitro human umbilical vein endothelial cells

A, B, C and D: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels by over-expression of miRNA-130a

E, F, G and H: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels by down-regulation of miRNA-130a.

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; anti-130a, down-regulation of miRNA-130a group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group.

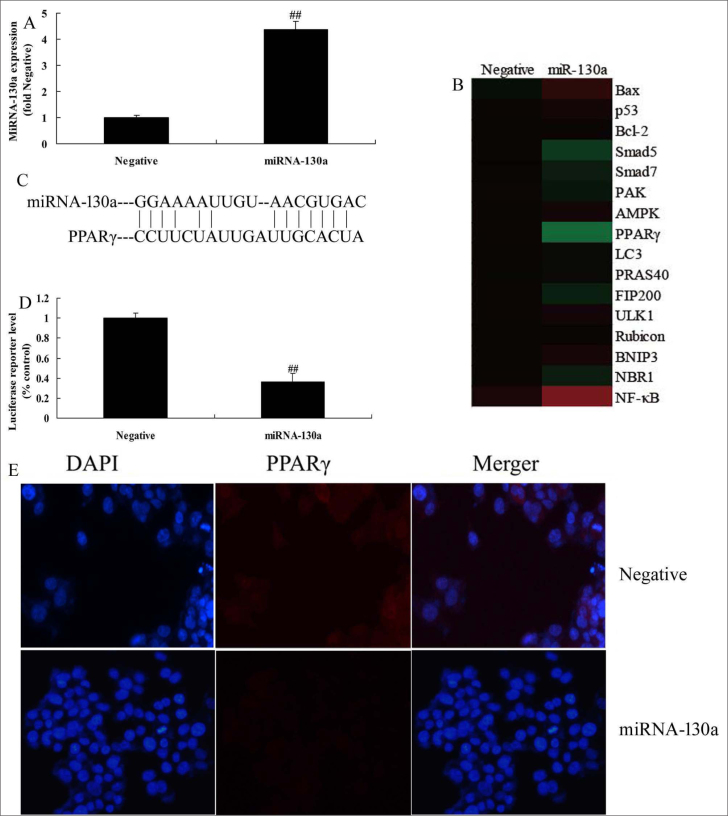

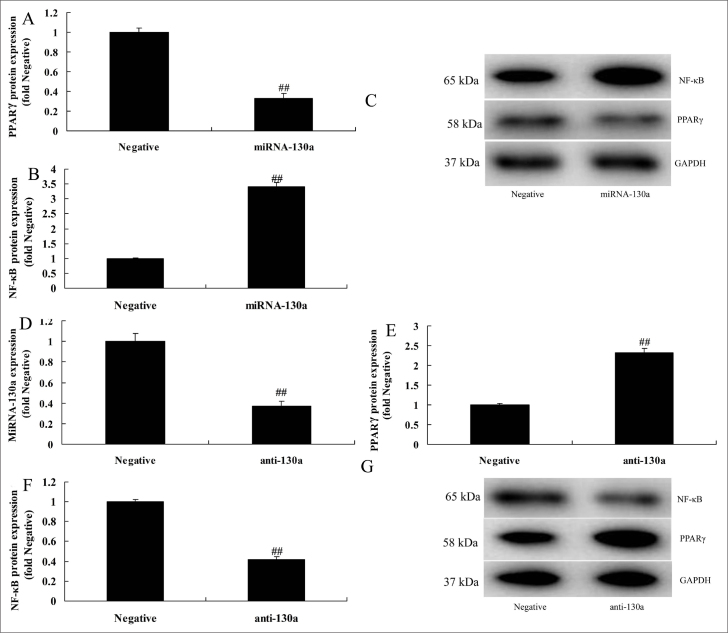

MiRNA-130a regulated PPARγ/NF-κB in HUVECs in vitro

In this study, we analyzed the mechanism of miRNA-130a in AS. Typically, miRNA-130a mimics was used to up-regulate miRNA-130a expression in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS (Fig. 3a). The results of the heat map revealed that over-expression of miRNA-130a reduced the expression of PPARγ and induced that of NF-κB in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS compared with those in the negative group (Fig. 3b). Moreover, miRNA-130a targeted PPARγ, and miRNA-130a over-expression could increase the luciferase reporter activity compared with that in the negative control group (Fig. 3c and 3d). Over-expression of miRNA-130a suppressed the expression of PPARγ compared with that in the negative group (Fig. 3e). Then, miRNA-130a would reduce the PPARγ activity protein expression whereas induce that of NF-κB in HUVECs LPS-induced HUVECs vitro model of AS, comparison with that in negative group (Fig. 4a–4c). Also, the expression of miRNA-130a in HUVECs LPS-induced HUVECs vitro model of AS was reduced by si-miRNA-130a, comparison with that in negative group (Fig. 4d). Our results suggested that down-regulation of miRNA-130a would induce the PPARγ activity protein level and suppress that of NF-κB activity protein level in LPS-induced HUVECs vitro model of AS, comparison with that in negative group (Fig. 4e–4g).

Figure 3.

Over-expression of miRNA-130a regulates PPARγ/NF-κB in in vitro human umbilical vein endothelial cells

A: qPCR for miRNA-130a expression

B: gene chip

C, D, and E: 3′-UTR of PI3K is a direct target site for miRNA-130a, luciferase activity levels, and PPARγ expression

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group.

Figure 4.

MiRNA-130a regulates PPARγ/NF-κB in in vitro human umbilical vein endothelial cells

A, B, and C: PPARγ and NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis and by over-expression of miRNA-130a

D: qPCR for miRNA-130a expression

E, F, and G: PPARγ and NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis and by down-regulation of miRNA-130a.

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; anti-130a, down-regulation of miRNA-130a group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group.

Activation of PPARγ diminish the function of miRNA-130a in pro-inflammation effect in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model

The role of PPARγ in diminishing the function of miRNA-130a in pro-inflammation effect in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model was also explored. Our findings indicated that PPARγ (2 μM of GW1929) could promote the protein expression of PPARγ and suppress that of NF-κB following miRNA-130a over-expression in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS (Fig. S1a–S1c). Besides, activation of PPARγ could reduce the effects of miRNA-130a on increasing the levels of IL-18, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS compared with those in the miRNA-130a group (Fig. S1d–S1g).

Inhibition of NF-κB diminishes the function of miRNA-130a in pro-inflammation effect in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model

The function of NF-κB in the mechanism of miRNA-130a in pro-inflammation effects in the LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS was also explored. Our results indicated that si-NF-κB could reduce the protein expression of NF-κB following over-expression of miRNA-130a in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS (Fig. S2a, S2b). However, si-NF-κB could reduce the effects of miRNA-130a on increasing the levels of IL-18, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS compared with that in over-expression of miRNA-130a group (Fig. S2c–S2f). Therefore, these results showed that NF-κB participated in the pro-inflammation effects of miRNA-130a in LPS-induced HUVECs in vitro model of AS.

Discussion

AS is a systemic disease involving multiple cells, factors, and steps. It is induced by the action of various injury stimulations on the arterial wall, but its pathogenesis remains incompletely illustrated yet (17). miRNA is a class of non-coding small molecular single-strand RNA, which is highly conserved in evolution (about 22 base groups) and can negatively regulate gene expression at the post-transcription level. Multiple studies have verified that miRNA is closely related to AS (15). Typically, plaque formation, development, rupture, and thrombosis are regulated by miRNA (18). Classical AS process can be divided into four stages, including initiation (endothelial activation and inflammation), genesis (sub-intima lipid deposition and foam cell formation), progression (smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, enlarged necrotic lipid nucleus in the plaque, and angiogenesis), and endpoint (unstable plaque rupture inducing acute coronary artery event) (19). This study demonstrated that miRNA-130a expression was increased in mice with AS. Jia et al. (20) have shown that miR-130a expression in patients with coronary heart disease was down-regulated.

AS is a complicated process involving inflammation, lipid, endocrine, as well as metabolic disorders (21). PPARγ is one of the current research hotspots for AS treatment, which can suppress the inflammatory response-related gene transcription (22). In addition, it can antagonize the expression of some inflammatory factors of AS to slow down plaque development. Studies show that although high PPARγ expression can be found in the human AS plaque, only a tiny quantity of PPARγ expression can be found in the normal artery. Besides, high PPARγ expression can be seen in smooth muscle cells during early AS, and its expression quantity persistently increases with disease progression (23). Increased expression can be observed in smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and foam cells, demonstrating that PPARγ plays a crucial role during AS process (23). This study showed that over-expression of miRNA-130a reduced PPARγ protein expression and stimulated NF-κB protein expression in in vitro HUVECs. Activation of PPARγ reduced the pro-inflammation effect of miRNA-130a in the in vitro model of AS. Lin et al. (24) have shown that miR-130a suppressed PPARγ interaction with 3′UTR of PPARγ mRNA in non-small cell lung cancer. This indicates that PPARγ suppression by miRNA-130a is important for sensitizing systemic inflammation of AS.

Upregulation of inflammatory factor levels has long been considered to promote AS-related injury. Numerous inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, are related to AS and other cardiovascular diseases (25). NF-κB is a key factor in the inflammatory response, which can regulate several key enzymes in LDL modification and inflammatory mediator formation in early AS. PPAR is a transcription regulatory factor that participates in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and AS. It includes three subtypes, namely PPARα, β/δ, and γ (22). Of them, PPARγ can suppress inflammatory response and regulate cell proliferation and migration to restrain AS (23). In addition, PPARγ ligand or agonist can restrain the activities of monocyte/macrophage transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB. It can also reduce the inflammatory factor TNF-α to regulate the inflammatory response in AS and prevent AS formation (12). We found that the suppressed NF-κB using si-NF-κB reversed the pro-inflammation effects of miRNA-130a in AS in vitro model. Wang et al. (14) have reported that miR-130a upregulates the mTOR pathway in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma by regulating NF-κB expression. Our results support a pivotal pro-inflammation function of miRNA-130a in the pathological development of AS by NF-κB/PPARγ.

Study limitations

In this study, the sample number of six mice was relatively low and is a limitation. Further studies with larger samples and mores model are warranted. However, the data from our study indicates that miRNA-130a may regulate inflammation of AS.

Conclusion

The results of our study demonstrate that miRNA-130a expression was increased in atherosclerotic mice. Over-expression of miRNA-130a increased inflammation factor levels in in vitro HUVECs through the induction of NF-κB expression by PPARγ. Therefore, miRNA-130a might be a novel molecular target for AS therapy.

HIGHLIGHTS

MiRNA-130a expression was up-regulated in atherosclerotic mice;

MiRNA-130a promotes inflammation in model of atherosclerosis;

MiRNA-130a accelerates atherosclerosis;

MiRNA-130a inhibits inflammation by the induction of PPARγ to suppress NF-κB expression in model of atherosclerosis

Supplementary Information

Activation of PPARγ reduced the effect of miRNA-130a on inflammation in in vitro model

A, B, and C: PPARγ and NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis

D, E, F, and G: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; PPARγ, over-expression of miRNA-130a and PPARγ group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group, **P<0.01 comparison with over-expression of miRNA-130a group.

Inhibition of NF-κB reduced the effect of miRNA-130a on inflammation in in vitro model

A and B: NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis

C, D, E, and F: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; anti- NF-κB, over-expression of miRNA-130a and si-NF-κB group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group, **P<0.01 comparison with over-expression of miRNA-130a group.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author contributions: Concept – Y.Li; Design – F.L.; Supervision – Y.Li; Fundings – Y.Li; Materials – F.L.; Data collection &/or processing – Y.D.; Analysis &/or interpretation – F.L.; Literature search – Y.Liu; Writing – F.L.; Critical review – Y.Li

References

- 1.Mita T, Katakami N, Yoshii H, Onuma T, Kaneto H, Osonoi T, et al. Collaborators on the Study of Preventive Effects of Alogliptin on Diabetic Atherosclerosis (SPEAD-A) Trial. Erratum. Alogliptin, a Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitor, Prevents the Progression of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The Study of Preventive Effects of Alogliptin on Diabetic Atherosclerosis (SPEAD-A) Diabetes Care. 2016;39:139–48. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamudu HM, Jones A, Paul T, Subedi P, Wang L, Alamian A, et al. Geographic and Individual Correlates of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in an Asymptomatic Rural Appalachian Population. Am J Med Sci. 2018;355:140–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randrianarisoa E, Lehn-Stefan A, Wang X, Hoene M, Peter A, Heinzmann SS, et al. Relationship of Serum Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Levels with early Atherosclerosis in Humans. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26745. doi: 10.1038/srep26745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santulli G. microRNAs Distinctively Regulate Vascular Smooth Muscle and Endothelial Cells: Functional Implications in Angiogenesis, Atherosclerosis, and In-Stent Restenosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;887:53–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22380-3_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menghini R, Casagrande V, Federici M. MicroRNAs in endothelial senescence and atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:924–30. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novák J, Olejníčková V, Tkáčová N, Santulli G. Mechanistic Role of MicroRNAs in Coupling Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;887:79–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22380-3_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li ZC, Han N, Li X, Li G, Liu YZ, Sun GX, et al. Decreased expression of microRNA-130a correlates with TNF-α in the development of osteoarthritis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2555–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao L, Guo Y, Wang L, Li G, Qian X, Zhang J, et al. Knockdown of miR-130a-3p alleviates spinal cord injury induced neuropathic pain by activating IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway. J Neuroimmunol. 2021;351:577458. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortuño Sahagún D, Márquez-Aguirre AL, Quintero-Fabián S, López-Roa RI, Rojas-Mayorquín AE. Modulation of PPAR-γ by Nutraceutics as Complementary Treatment for Obesity-Related Disorders and Inflammatory Diseases. PPAR Res. 2012;2012:318613. doi: 10.1155/2012/318613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Z, Dong J, Wu W, Yang T, Wang T, Guo L, et al. Resolvin D1 attenuates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through a process involving the PPARγ/NF-κB pathway. Respir Res. 2012;13:110. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Liu J, Niu G, Xu Q, Chen Q. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein induces Toll-like receptor 2-dependent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression and promotes inflammatory responses in human macrophages. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:2921–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Zhao H, Ren X. Estrogen and progestogen inhibit NF-κB in atherosclerotic tissues of ovariectomized ApoE (−/−) mice. Climacteric. 2016;19:357–63. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2016.1167867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou F, Liu D, Ning HF, Yu XC, Guan XR. The roles of p62/SQSTM1 on regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression in response to oxLDL in atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;472:451–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Zhang X, Tang W, Lin Z, Xu L, Dong R, et al. miR-130a upregulates mTOR pathway by targeting TSC1 and is transactivated by NF-κB in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:2089–100. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Huang R, Zhang L, Li S, Luo J, Gu Y, et al. A severe atherosclerosis mouse model on the resistant NOD background. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11:dmm033852. doi: 10.1242/dmm.033852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang JY, Gong YL, Li CJ, Qi Q, Zhang QM, Yu DM. Circulating MiRNA biomarkers serve as a fingerprint for diabetic atherosclerosis. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:2650–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yilmaz SG, Isbir S, Kunt AT, Isbir T. Circulating microRNAs as Novel Biomarkers for Atherosclerosis. In Vivo. 2018;32:561–5. doi: 10.21873/invivo.112276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao Z, Wu F, Shan Y. Identification of key genes and miRNAs associated with carotid atherosclerosis based on mRNA-seq data. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e9832. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia QW, Chen ZH, Ding XQ, Liu JY, Ge PC, An FH, et al. Predictive Effects of Circulating miR-221, miR-130a and miR-155 for Coronary Heart Disease: A Multi-Ethnic Study in China. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:808–23. doi: 10.1159/000478071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong W, Zhao X, Villacorta L, Rom O, Garcia-Barrio MT, Guo Y, et al. Brown Adipocyte-Specific PPARγ (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ) Deletion Impairs Perivascular Adipose Tissue Development and Enhances Atherosclerosis in Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1738–47. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi ST, Li YF, Guo YQ, Wang ZH. Effect of beta-3 adrenoceptor stimulation on the levels of ApoA-I, PPARα, and PPARγ in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014;64:407–11. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao LN, Zhou X, Lu YR, Li K, Gao S, Yu CQ, et al. Dan-Lou Prescription Inhibits Foam Cell Formation Induced by ox-LDL via the TLR4/NF-κB and PPARγ Signaling Pathways. Front Physiol. 2018;9:590. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin L, Lin H, Wang L, Wang B, Hao X, Shi Y. miR-130a regulates macrophage polarization and is associated with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:3088–96. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Yu P, Jiang H, Yang X, Zhao J, Zou Y, et al. The Essential Role of Pin1 via NF-κB Signaling in Vascular Inflammation and Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:644. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Activation of PPARγ reduced the effect of miRNA-130a on inflammation in in vitro model

A, B, and C: PPARγ and NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis

D, E, F, and G: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; PPARγ, over-expression of miRNA-130a and PPARγ group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group, **P<0.01 comparison with over-expression of miRNA-130a group.

Inhibition of NF-κB reduced the effect of miRNA-130a on inflammation in in vitro model

A and B: NF-κB by statistical analysis and Western blot analysis

C, D, E, and F: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 levels

Negative, negative control group; miRNA-130a, over-expression of miRNA-130a group; anti- NF-κB, over-expression of miRNA-130a and si-NF-κB group.

##P<0.01 comparison with negative group, **P<0.01 comparison with over-expression of miRNA-130a group.