Abstract

Purpose

To determine racial differences in intensive care unit (ICU) mortality outcomes among mechanically ventilated patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in a safety net hospital.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed a cohort of patients ≥ 18 years old with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV-2 disease associated respiratory failure who were treated with invasive mechanical ventilation and admitted to the ICU from May 1, 2020 – July 30 -2020 at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia – a safety net hospital. We evaluated the association between mortality and demographics, co-morbidities, inpatient laboratory, and radiological parameters.

Results

Among 181 critically ill mechanically ventilated African American patients treated at a safety net hospital, the mortality rate was 33%. On stratified analysis by race (Table 2), mortality rates were significantly higher in African Americans (39%) and Hispanics (26.3%), compared to Whites (18.9%). On multivariate regression, African Americans were 3 times more likely to die in the ICU compared to Whites (OR 3.1 95% CI 1.6 -5.5). Likewise, the likelihood of mortality was higher in Hispanics compared to Whites (OR 1.3 95% CI 1.0 -3.9).

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated a high ICU mortality rate in a cohort of mechanically ventilated patients with severe COVID-19 infection treated at a safety net hospital. African Americans and Hispanics had significantly higher risks of ICU mortality compared to Whites. These study findings further elucidate the disproportionately higher burden of COVID-19 infection in African Americans and Hispanics.

Keywords: African Americans, COVID-19, Critical care, Mechanical ventilation, Mortality

Introduction

Coronavirus diseases 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is responsible for more than 150 million cases and 3 million deaths worldwide as of June 1, 20211. In the United States, over 30 million confirmed cases and 600,000 deaths have been recorded as at the time of the writing of this manuscript. An estimated 25-70% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection will develop respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU)2, 3, 4.

Safety-net hospitals as defined by the Institute of Medicine have a legal mandate or mission to provide medical care to patients regardless of their ability to pay5. The patient population of safety net hospitals are predominantly ‘uninsured’ and on ‘Medicaid’, those of low socio-economic status especially minorities – African Americans and Hispanics which incidentally are the groups hardest hit by the pandemic6.

Though there is strong evidence to support disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection among African Americans and Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites7, 8, 9 there are conflicting results in the literature on the risks of hospitalization, severe illness, and mortality. Some studies have reported that Hispanics and African Americans are more likely to be hospitalized, require invasive mechanical ventilation, and die from COVID-19 related complications compared to non-Hispanic whites6 , 10. On the contrary, other studies did not demonstrate a difference in outcomes7 , 11 , 12. A study of COVID-19 patients in New York City showed that Black patients with COVID-19 had lower odds of critical illness and death compared to Whites13.

Currently, there is limited data on racial disparities in the outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients treated at safety-net hospitals that disproportionately treat vulnerable populations at risk of worse outcomes. We retrospectively evaluated a cohort of mechanically ventilated African American patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 associated respiratory failure at Grady Memorial Hospital (GMH), a 1000 – bed level 1 trauma and safety net hospital, and one of the largest academic medical centers in Georgia14.

Methods

Data were extracted from the hospital's electronic medical record system (EMR - Epic 2019 version). We identified patients with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection by a positive result on polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal or tracheal sample. We selected patients that were mechanically ventilated through endotracheal intubation for hypoxemic respiratory failure and admitted to the GMH intensive care unit (ICU) on both the Emory university school of medicine and Morehouse School of Medicine ICU service between May 1, 2020 – July 30, 2020.

We collected patient-level data including demographic information, chronic comorbidities, body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2, health insurance status, laboratory data, and chest computed tomography (CT) imaging reports upon admission to the ICU, length of stay in the ICU and mortality outcomes. Chronic comorbidities were extracted from the EMR using pre-existing corresponding International Classification of Diseases codes (ICD-9 or ICD-10).

The most recent Chest CT imaging obtained before ICU admission was evaluated and the reports dictated by the hospital radiologists were extracted. We reported percentages of total patients with completed tests for laboratory tests and clinical studies not performed on all the patients. Radiologic assessments and all laboratory testing were performed according to the clinical care needs of the patient. Targeted COVID-19 treatment was guided by the GMH treatment guidelines and protocol, availability of medications, and shared-decision making between the attending critical care specialist and patients and/or designated proxies. All patients were either discharged alive from the ICU or deceased by the time of data analysis and reporting of the study findings.

The Morehouse School of Medicine institutional review board (IRB) and the GMH research oversight committee approved the study (IRB approval no: 1671658-1) as a quality improvement initiative and minimal-risk research using data collected for routine clinical practice and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using version 3.5.2 of the R programming language (R Project for Statistical Computing; R Foundation). Continuous variables were summarized as median (interquartile range [IQR]), and categorical variables were described as frequency rates and percentages. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate continuous data for normality of distribution. We made Univariate comparisons between survivors and non-survivors using Pearson's Chi-Square and Mann-Whitney U tests. We imputed values for variables with less than 25% of the data missing using multiple imputation by fully conditional specification15. We evaluated the association between patients’ race and the likelihood of mortality in the ICU using a multiple logistic regression model. The covariates were selected based on previously published findings on outcomes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection2 , 4 , 7 , 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and the results of the univariate analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

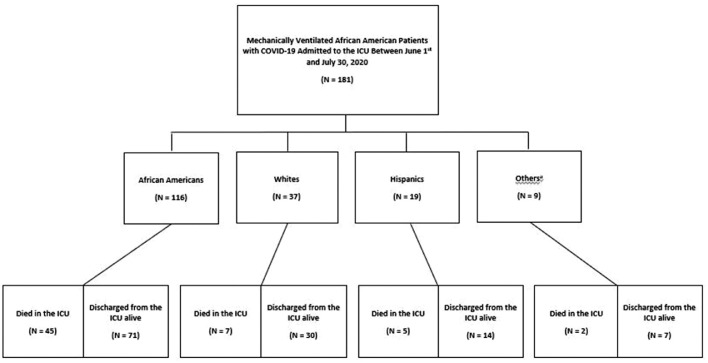

A total of 181 mechanically ventilated patients admitted to the ICU who had tested positive for COVID-19 were included in the study (Figure 1 ). The median age was 60 years [interquartile range {IQR}, 51-69)] and 54% of the study population was male. African Americans made up 64% of the study cohort, followed by Whites (20%) and Hispanics (11%). The overall mortality rate was 33% and the median duration of stay on the mechanical ventilator and in the ICU were 7 days [interquartile range {IQR}, 2-12)] and 9 days [interquartile range {IQR}, 5-18.25)] respectively. Among patients that died in the ICU, African Americans had the highest mortality rate of 76% followed by Whites with a mortality rate of 11% (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the outcomes of study patients who were admitted to the ICU and received invasive mechanical ventilation due to severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection 65% (n=116/181) of the study population was African Americans with associated ICU mortality of 38% (n=45/116) aOther races: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics Patients with Severe COVID-19 Infection Receiving Invasive Mechanical Ventilation and Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit.

| Variables | All | Survived | Mortality | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total–no (%) | 181 | 122 (67) | 59 (33) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 60 (51-69) | 52 (54-56) | 64 (62-66) | < 0.01 |

| < 55 years | 51 (28.2) | 46 (37.7) | 5 (8.5) | 0.33 |

| 55–64 years | 59 (32.6) | 33 (27) | 26 (44.1) | <0.01 |

| 65–74 years | 44 (24.3) | 28 (23) | 16 (27.1) | 0.21 |

| >75 years | 27 (14.9) | 15 (12.3) | 12 (20.3) | 0.04 |

| Race | ||||

| Black/African American | 116 (64.1) | 71 (58.2) | 45 (76.3) | 0.04 |

| White | 37 (20.4) | 30 (24.6) | 7 (11.9) | 0.05 |

| Hispanics | 19 (10.5) | 14 (11.5) | 5 (8.5) | 0.17 |

| Others* | 9 (5) | 7 (5.7) | 2 (3.4) | 0.46 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 84 (46.4) | 60 (49.2) | 24 (40.7) | 0.09 |

| Male | 97 (53.6) | 62 (50.8) | 35 (59.3) | 0.03 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Medicaid only | 12 (6.6) | 9 (7.4) | 3 (5.1) | 0.63 |

| Medicare only | 26 (14.4) | 14 (11.5) | 12 (20.3) | 0.27 |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 51 (28.2) | 34 (27.9) | 17 (28.8) | 0.35 |

| Private Insurance/Self Pay | 43 (23.8) | 29 (23.8) | 14 (23.7) | 0.49 |

| Uninsured | 49 (27.1) | 36 (29.5) | 13 (22) | 0.07 |

| Comorbid Diseases | ||||

| Asthma | 19 (10.5) | 15 (12.3) | 4 (6.8) | 0.19 |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | 31 (17.1) | 24 (19.7) | 7 (11.9) | 0.32 |

| Cancera | 19 (10.5) | 13 (10.7) | 6 (10.2) | 0.47 |

| CHF (Congestive heart failure (CHF) | 41 (22.7) | 29 (23.8) | 12 (20.3) | 0.15 |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) 3 and aboveb | 30 (16.6) | 18 (14.8) | 12 (20.3) | 0.02 |

| Chronic liver disease | 19 (10.5) | 13 (10.7) | 6 (10.2) | 0.39 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 34 (18.8) | 21 (17.2) | 13 (22) | 0.13 |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) | 37 (20.4) | 17 (13.9) | 17 (28.8) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM)c | 78 (43.1) | 57 (46.7) | 21 (35.6) | 0.27 |

| HIV | 7 (3.9) | 7 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 0.81 |

| Hypertension | 134 (74) | 72 (59) | 42 (71.2) | <0.01 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) | 34 (18.8) | 23 (18.9) | 11 (18.6) | 0.7 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||

| < 30 kg/m2 | 57 (31.5) | 43 (35.2) | 14 (23.7) | 0.08 |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 to < 35 kg/m2 | 72 (39.8) | 53 (43.4) | 19 (32.2) | 0.19 |

| ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 52 (28.7) | 26 (21.3) | 26 (44.1) | <0.01 |

| >1 Comorbidities | 140 (77.3) | 86 (70.5) | 54 (91.5) | <0.01 |

| Tobacco smoking | ||||

| Never smoker | 55 (30.4) | 47 (38.5) | 8 (13.6) | 0.24 |

| Previous smoker | 65 (35.9) | 39 (32) | 26 (44.1) | 0.16 |

| Current Smoker | 61 (33.7) | 36 (29.5) | 25 (42.4) | 0.43 |

| On ACE-I/ARB medication | ||||

| No | 96 (53) | 59 (48.4) | 37 (62.7) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 85 (47) | 63 (51.6) | 22 (37.3) | 0.09 |

| Length of Stay, median (IQR) [range], d | 0.29 | |||

| Length of mechanical ventilator days | 7 (2-12) | 6 (3 - 9) | 7 (3 – 11) | 0.17 |

| Length of stay in the ICU | 9 (5-18.25) | 8 (5-19) | 11 (6.75 – 17.25) | 0.3 |

Among patients that died in the ICU, African Americans had the highest mortality rate of 76%

Patients in the mortality group were more likely to be males, older, obese and have multiple comorbidities.

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, ICU: Intensive care unit

*Other races: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

The p-values signify exact 2-sided Chi-Square test results for binary outcomes and Mann-Whitney U test results for continuous outcomes.

ACE-I: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker

Statically significant p values in bold

Patients with history of solid tumors

Patients with Chronic kidney disease stage 3 or higher or end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis.

Patients with both Types 1 and 2 DM

Patients in the mortality group were more likely to be males (59.3% vs. 50.8%, P = 0.03), older (64 years IQR, 62-66 vs.52 years IQR, 52-56 years, p < 0.01), in the 55-64-year range (44.1% vs. 27%, p < 0.01), and > 75 years of age (20.3% vs. 12.3% P =0.04) (Table 1). Additionally, mortality rate was higher in patients with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 (43.4% vs. 32.2%, p < 0.01), prior cerebrovascular accident (CVA) compared to patients without CVA (62% vs. 32%, p < 0.01), CKD 3 and above (20.3% vs. 14.8%, p = 0.02), in patients with hypertension compared to those without hypertension (71.2% vs. 59%, p <0.01) and multiple comorbidities (91.5% vs. 70.5%, p<0.01).

On stratified analysis by race (Table 2 ), mortality rates were significantly higher in African Americans (39%) and Hispanics (26.3%) compared to Whites (18.9%). African Americans and Hispanics were also found to have higher rates of multiple comorbidities relative to Whites. There were no statistically significant differences in socio-demographic and inpatient clinical characteristics across the different ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Inpatient Characteristics of Patients Stratified by Race.

| Variables | Total | Black/African American | White | Hispanics | Others* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total – no (%) | 181 | 116 (64) | 37 (20.4) | 19 (10.5) | 9 (4.9) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 84 (46.4) | 54 (46.6) | 17 (45.9) | 10 (52.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.14 |

| Male | 97 (53.6) | 62 (53.4) | 20 (54.1) | 9 (47.4) | 6 (66.7) | 0.27 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 65 years | 104 (57.5) | 61 (52.6) | 24 (64.9) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (55.6) | 0.33 |

| > 65 years | 71 (39.2) | 49 (42.2) | 13 (35.1) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (44.4) | 0.07 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 52 (0) | 37 (31.9) | 8 (21.6) | 6 (31.6) | 1 (11.1) | 0.02 |

| >1 Comorbidities | 140 (77.3) | 103 (88.8) | 21 (56.8) | 13 (68.4) | 3 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein (N=168) | 163 (90.1) | 111 (95.7) | 30 (81.1) | 15 (78.9) | 7 (77.8) | 0.75 |

| Elevated D-Dimer (N=171) | 167 (92.3) | 105 (90.5) | 29 (78.4) | 26 (136.8) | 7 (77.8) | 0.23 |

| Elevated Ferritin (N=170) | 167 (92.3) | 110 (94.8) | 33 (89.2) | 16 (84.2) | 8 (88.9) | 0.47 |

| Elevated LDH (N=171) | 163 (90.1) | 109 (94) | 28 (75.7) | 18 (94.7) | 8 (88.9) | 0.53 |

| Abnormal LFT | 166 (91.7) | 111 (95.7) | 32 (86.5) | 16 (84.2) | 7 (77.8) | 0.33 |

| Lymphopenia | 127 (70.2) | 89 (76.7) | 22 (59.5) | 13 (68.4) | 3 (33.3) | 0.17 |

| Elevated Troponin (N=160) | 113 (62.4) | 81 (69.8) | 18 (48.6) | 11 (57.9) | 3 (33.3) | 0.39 |

| Radiological evidence on CT chest | ||||||

| None | 18 (9.9) | 9 (7.8) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (15.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0.08 |

| Bilateral ground-glass opacity | 77 (42.5) | 53 (45.7) | 13 (35.1) | 8 (42.1) | 3 (33.3) | 0.19 |

| Lobar patchy opacity | 42 (23.2) | 28 (24.1) | 9 (24.3) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (11.1) | 0.11 |

| Bilateral patchy opacity | 44 (24.3) | 26 (22.4) | 11 (29.7) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (33.3) | 0.07 |

| COVID-19 targeted treatment | ||||||

| Azithromycin only | 34 (18.8) | 17 (14.7) | 11 (29.7) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0.14 |

| Hydroxychloroquine only | 41 (22.7) | 29 (25) | 8 (21.6) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (22.2) | 0.22 |

| Azithromycin + Hydroxychloroquine | 49 (27.1) | 34 (29.3) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (31.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.35 |

| Remdesivir | 57 (31.5) | 36 (31) | 12 (32.4) | 6 (31.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.17 |

| ICU Outcomes | ||||||

| Mortality | 59 (32.6) | 45 (38.8) | 7 (18.9) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (22.2) | <0.01 |

| Length of Stay, median (IQR) [range], d | ||||||

| Length of mechanical ventilator days | 7 (2-12) | 8 (2-14) | 7 (2-12) | 6 (2-12) | 7 (2-12) | 0.17 |

| Length of stay in the ICU | 9 (5-18.25) | 10 (6-16.25) | 8 (4-16) | 8 (4-16.5) | 8 (4-16) | 0.21 |

Mortality rates were significantly higher in African Americans and Hispanics compared to Whites There were no statistically significant differences in socio-demographic and inpatient clinical characteristics across the different ethnic groups.

The p-values signify exact 2-sided Chi-Square test results for binary outcomes and Mann-Whitney U test results for continuous outcomes.

Abnormal LFTs were defined as the elevation of one or more of the following liver enzymes in serum: ALT >40 U/L, AST >40 U/L, gamma-glutamyltransferase >49 U/L, alkaline phosphatase >135 U/L, and total bilirubin >17.1 μmol/L. Reference range for lab values: Hematocrit (male) - 40.3-53.1%, Hematocrit (female) - 33.6-44.6%, WBC- 3.8 – 10.7 K/mcL, Lymphocyte - 0.5-4.5 K/mcL, Platelet 148-362 K/mcL, Ferritin 24-336 ng/mL, LDH - 91-180 U/L, D-Dimer- 10-42 U/L

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers

Data on measurement of Ferritin were missing for 11 patients (6%)

Data on measurement of CRP were missing for 13 patients (7%)

Data on measurement of D-Dimer were missing for 10 patients (6%)

Data on measurement of LDH were missing for 10 patients (6%)

Data on measurement of Troponins were missing for 21 patients (12%)

Statically significant p values in bold

ICU: Intensive care unit

*Other races: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

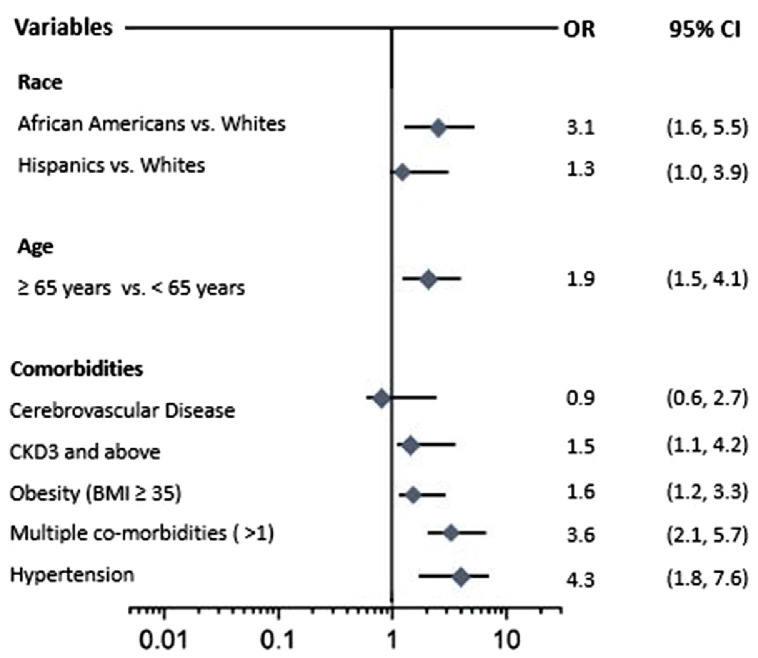

On multivariate regression, African Americans were 3 times more likely to die in the ICU compared to Whites (OR 3.1 95% CI 1.6 -5.5). Likewise, the likelihood of mortality was higher in Hispanics compared to Whites (OR 1.3 95% CI 1.0 -3.9). Age ≥ 65 years (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5, 4.1) history of CKD 3 and above (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1, 4.2), Hypertension (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.8, 7.6), BMI ≥ 35 (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2, 3.3), and multiple medical co-morbidities (OR 3.6, 95% CI 2.1, 5.7) were also significantly associated with increased risk of ICU mortality (Figure 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Association between race and mortality in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients adjusted for age and comorbidities. African Americans were 3 times more likely to die in the ICU compared to Whites. Age ≥ 65 years, history of CKD 3 and above, Hypertension, and multiple medical co-morbidities were also significantly associated with increased risk of ICU mortality.

Discussion

In this study, we found significant racial differences in the ICU mortality rates among a cohort of patients with severe COVID-19 infection treated with invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU. African American patients. Significantly higher mortality rates were seen in African Americans and Hispanics compared to Whites. Additionally, African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to experience ICU mortality relative to Whites. Other significant predictors of mortality were older age (> 65 years), medical history of hypertension, CKD 3 and above, BMI ≥ 35, and multiple medical comorbidities.

We found a higher mortality rate in our study than previously reported in the literature. In a cohort of 85 COVID-19 patients (26% African Americans) requiring mechanical ventilation, the mortality rate in the African American population was 27.3%21. In a study conducted by Auld et al. in three acute-care hospitals in Atlanta, Georgia, from March to April 2020 comprising 70% African Americans, the mortality rate among the mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU was 35.7%. The authors reported aggregated mortality rate across all ethnicities making it difficult to determine mortality outcomes attributable to the African American race22. Similarly, another study cohort of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients with 45% African Americans admitted to two academic hospitals in the Midwestern part of the US also reported an aggregated mortality rate of 20.9%23.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the impact of race and social inequalities on healthcare outcomes to a vantage position in recent public health discussions. Diverse reasons have been attributed to the disproportionate increase in COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality rates among Blacks and Hispanics compared to Whites including structural socio-economic inequities, relative lack of access to adequate healthcare or delays in receiving healthcare. In our study, we noted that African Americans and Hispanics had significantly higher proportion of multiple comorbidities and patients with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 than Whites which likely contributed to the poorer outcomes2.

Differential receipt of medical care from low resource settings among racial and ethnic minority groups have also been implicated in worse health outcomes24. However, this is unlikely the case in our study as all the patients were afforded the same level of medical treatment at a safety net hospital which provides care to the underserved, uninsured, under-insured, publicly insured and low socio-economic population regardless of race. Though studies have associated inferior healthcare outcomes with receiving medical care at safety net hospitals25, such evaluation is beyond the scope of this study. Given that safety net hospitals provide care to a substantial proportion of COVID-19 patients, it will be interesting to evaluate the impact of receiving care in safety net hospital on outcomes in COVID-19 infection.

Patients socio-demographics, co-morbidities and inpatient characteristics have been shown to contribute to the outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. In our study, older age, multiple co-morbid conditions, hypertension, CKD 3 and above and obesity with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were significantly associated with increased risk of mortality in our study which is consistent with the currently existing literature2 , 3 , 22 , 26 , 27.

We recognize that our study has some limitations. This was an observational study and there is a likelihood of confounders not accounted for28. Also, data was pooled from a single center in Atlanta, Georgia, therefore our findings should be interpreted with caution considering institutional differences and practices in the management of COVID-19 patients which may impact outcomes.

Furthermore, our results may not be generalizable to other regions of the country. Lastly, we are unable to control for possible coding errors on the part of clinicians because we relied on administrative ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for the co-morbid conditions included in this study.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated a high ICU mortality rate in a cohort of mechanically ventilated patients with severe COVID-19 infection treated in a safety net hospital. African Americans and Hispanics had significantly higher risks of ICU mortality compared to Whites. These study findings further elucidate the disproportionately higher burden of COVID-19 infection in African Americans and Hispanics.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Morehouse School of Medicine institutional review board (IRB) and the GMH research oversight committee approved the study (IRB approval no: 1671658-1) as a quality improvement initiative and minimal-risk research using data collected for routine clinical practice and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors of this manuscript have no financial disclosure or conflict of interests to report. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Lancet Inf Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00434-0. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html%0Ahttps://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6%0Ahttps://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes among 5700 Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eastin C, Eastin T. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:710. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vahidy FS, Drews AL, Masud FN, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients during Initial Peak and Resurgence in the Houston Metropolitan Area. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:998–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwanziger J, Khan N. Safety-net hospitals. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65:478–495. doi: 10.1177/1077558708315440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qeadan F, VanSant-Webb E, Tingey B, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes exist despite comparable Elixhauser comorbidity indices between Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Whites. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Adult Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:545–550. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Across New York City Boroughs. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2192–2195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2534–2543. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa2011686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulson M, Geary A, Annesi C, et al. National Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes between Black and White Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, et al. Association of Race With Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, et al. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Aff. 2020;39:1253–1262. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Adhikari S, et al. Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospitalization and Mortality in Patients With COVID-19 in New York City. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olanipekun T, Effoe VS, Olanipekun O, et al. Factors influencing the uptake of influenza vaccination in African American patients with heart failure: Findings from a large urban public hospital. Hear Lung. 2020;49:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16:219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastin C, Eastin T. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:710. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause M, Douin DJ, Kim KK, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Mechanically Ventilated COVID-19 Patients—An Observational Cohort Study. J Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0885066620954806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auld SC, Caridi-Scheible M, Blum JM, et al (2020) ICU and Ventilator Mortality among Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019∗. Crit Care Med E799–E804. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Twigg HL, Khan SH, Perkins AJ, et al. Mortality Rates in a Diverse Cohort of Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Novel Coronavirus in the Urban Midwest. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0187. doi: 10.1097/cce.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: Examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandjian M, Williamson C, Xia Y, et al. Association of Hospital Safety Net Status With Outcomes and Resource Use for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the United States. J Intensive Care Med. 2021 doi: 10.1177/08850666211007062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rola P, Farkas J, Spiegel R, et al. Rethinking the early intubation paradigm of COVID-19: Time to change gears? Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2020;7:78–80. doi: 10.15441/ceem.20.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wunsch H. Mechanical ventilation in COVID-19: Interpreting the current epidemiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1385ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedgwick P. Bias in observational study designs: Cross sectional studies. BMJ. 2015:350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]