Abstract

Objective The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is an unexpected universal problem that has changed health care access across the world. Telehealth is an effective solution for health care delivery during disasters and public health emergencies. This study was conducted to summarize the opportunities and challenges of using telehealth in health care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods A structured search was performed in the Web of Science, PubMed, Science Direct, and Scopus databases, as well as the Google Scholar search engine, for studies published until November 4, 2020. The reviewers analyzed 112 studies and identified opportunities and challenges. This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols. Quality appraisal was done according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018. Thematic analysis was applied for data analysis.

Results A total of 112 unique opportunities of telehealth application during the pandemic were categorized into 4 key themes, such as (1) clinical, (2) organizational, (3) technical, and (4) social, which were further divided into 11 initial themes and 26 unique concepts. Furthermore, 106 unique challenges were categorized into 6 key themes, such as (1) legal, (2) clinical, (3) organizational, (40 technical, (5) socioeconomic, and (6) data quality, which were divided into 16 initial themes and 37 unique concepts altogether. The clinical opportunities and legal challenges were the most frequent opportunities and challenges, respectively.

Conclusion The COVID-19 pandemic significantly accelerated the use of telehealth. This study could offer useful information to policymakers about the opportunities and challenges of implementing telehealth for providing accessible, safe, and efficient health care delivery to the patient population during and after COVID-19. Furthermore, it can assist policymakers to make informed decisions on implementing telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by addressing the obstacles ahead.

Keywords: telehealth, telemedicine, COVID-19, opportunities, challenges

Background and Significance

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) and the disease it causes, that is, novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), have made a tragic and fundamental change in the world. 1 This pandemic may continue for at least several months. The health care setting has experienced a significant change in this pandemic in two ways. 2 The first is the need to allocate limited medical and logistic resources to COVID-19-positive patients, 3 and the second is protecting health care providers and patients from virus exposure. 4 5 In this context, health care organizations (HCOs) should also continue to provide care in other fields. 6 However, the high rate of virus spread 7 has forced HCOs to take novel measures among which telehealth seems to be the most effective and efficient one. 8

According to the American Telemedicine Association (AMA), telehealth is defined as “technology-enabled health and care management and delivery systems that extend capacity and access” 9 and includes modalities such as “remote patient monitoring, telehealth, teleconsultation, and the use of mobile application-based technology.” 10 It has developed rapidly in recent years, and the pandemic has accelerated its implementation and usage. 11 Telehealth technologies have been implemented in almost all aspects of care, including evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, therapy, follow-up, and monitoring. 12 13 14 15

In the COVID-19 pandemic era, formal quarantine, social distancing, and the high probability of nosocomial conditions have caused challenges in the continuity of care for patients and HCOs. 16 In these circumstances, telehealth is a more feasible and cost-effective alternative to face-to-face care. 11

Several studies have investigated telehealth implementation in diverse health care settings in the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Many studies illustrated the circumstances and the steps taken to implement telehealth. 17 18 Some studies reported care delivery to patients in a specific field. 19 20 21 Others provided a specialty perspective on telehealth. 22 23 24 Moreover, several studies explained telehealth application in various uncommon cases, including self-removing a drain, 25 home dialysis, 26 appraising drug efficacy, 27 and collecting samples for COVID-19. 28 Furthermore, some authors reported the opportunities of telehealth in the management and monitoring of COVID-19-positive patients. 29 30 It can be concluded that although COVID-19 has masked the faces, it has unmasked the face of telehealth.

Despite the numerous benefits, telehealth has confronted several challenges, including technical issues (network connectivity and user interface), limited physical examination, privacy issues, participants' literacy level, cost, reimbursement, and regulatory barriers. 31 32 33 Recognizing the opportunities and challenges of using telehealth in this course will help to take the necessary measures to use the capacities of the health system more efficiently in future. To the best of the authors' knowledge, no study has reviewed the opportunities and challenges of using the telehealth technology during the COVID-19 pandemic comprehensively.

Objective

This study was conducted to answer the following main questions: (1) what are the opportunities of using telehealth for health care delivery during the COVID-19 era? And (2) what are the challenges of using telehealth for health care delivery during the pandemic?

Methods

This study was a comprehensive literature review of all publications related to telehealth use and its subdomains during the COVID-19 pandemic to summarize the data about telehealth subdomains, modalities, services, opportunities, and challenges in the period of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) methodology suggested by Moher et al 34 in five steps including literature review, control of inclusion and exclusion criteria, selection of studies, quality assessment, and data extraction and synthesis.

Literature Review: Databases and Keywords

Four large databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Science Direct, as well as the Google Scholar search engine were searched for articles about using telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic era published until November 4, 2020. Combinations of the following keywords were used in the search: “eHealth” OR “Telehealth” OR “Telemedicine” OR “Mobile Health” OR “mHealth” OR “teleconsultation” OR “telecare” OR virtual care, OR online care, OR telemonitoring AND “novel coronavirus” OR “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2.” The search for the keywords in the above databases was conducted on November 4, 2020. The details of the search strategy in the databases are provided in Supplementary Appendix A (available in the online version).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

This study included (1) studies published in English language only, (2) studies whose full texts were available based on access to published papers, (3) studies on telehealth use and all its subdomains (telemedicine, mobile health, and telecare) during the COVID-19 pandemic, and, (4) studies published until November 4, 2020.

Exclusion Criteria

The following studies were excluded: (1) studies whose full texts were impossible to access, (2) review articles (but their reference lists were evaluated for completion of search), and (3) studies suggesting models for using telehealth in the COVID-19 era not yet applied during the pandemic.

Studies Selection

A screening process by titles, abstracts, and full-text was conducted by two authors independently. In case of disagreement, the authors reached consensus by discussion.

Quality Assessment

In this process, the quality of the studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 provided by Hong et al 35 which offers valid criteria for the assessment of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies. Two authors independently assessed the quality of the studies based on the MMAT tool criteria. The MMAT consists of two common screening questions and five specific criteria per five categories of study designs (qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies) to appraise the methodological quality. For example, the checklist for quality appraisal of quantitative descriptive studies consists of five criteria including (1) is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question?; (2) is the sample representative of the target population?; (3) are the measurements appropriate?; (4) is the risk of nonresponse bias low?; and (5) is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question?

Disagreements between the two authors were resolved through consultation with an out-of-study methodologist. Afterward, studies that did not meet at least three of the MMAT criteria were excluded. Furthermore, the authors conducted a manual search and checked the reference lists for both research and review articles to find all eligible full-text articles; however, none were added to the final articles for scrutiny.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

After the quality assessment process, the full text of each article was reviewed, and the data were extracted from the studies using a predesigned form ( Supplementary Appendix B , available in the online version). The form included basic characteristics of the study such as the authors' names, location, design, and purpose, as well as specific data, such as type of services provided through telehealth (consultation or treatment), the specialty field used, and the opportunities and challenges associated with e-health use in the COVID-19 era. In this study, we considered consultation as telecommunications between patient caregivers or between caregivers to discuss health issues, while treatment refer to the use of medicine, therapy, and others by health care providers to help decrease the symptoms and effects of a disease. Also, medical specialties were coded according the AMA classification and first author affiliation. 36

Data extraction was done by two authors, and disagreement between the authors, if any, was resolved by discussion. Thematic analysis was applied for the purpose of this study 37 due to the heterogeneity of studies in terms of design, setting, and applications, as well as opportunities and challenges. This analysis was conducted in three stages. 38 First, two authors independently coded the data of the articles. Disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion between the authors in two meetings. Second, similarities and differences between codes were determined, and codes were grouped into initial themes. Finally, analytic themes were developed beyond the primary data of the original articles to identify key messages. The extracted themes were first reviewed independently and then discussed by two authors in one session to achieve agreement. The findings regarding opportunities and challenges of telehealth application during COVID-19 pandemic were synthesized according to the thematic approach. This approach is applied to identify, extract, and summarize themes from included studies in literature reviews. 38 39

Results

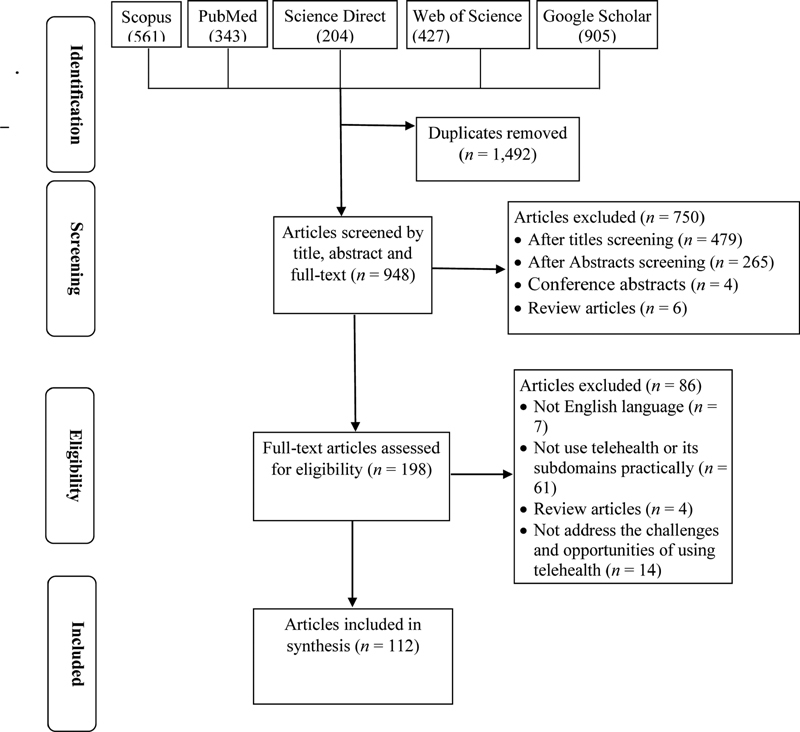

The database search yielded 2,440 articles of which 1,492 duplicates were removed. Titles, abstracts, and full texts of 948 unique articles were screened but 570 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. After the full-text screening of the remaining articles ( n = 198), 86 additional papers did not meet inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically accelerated the use of telehealth care for patients across the world. In this study, 112 eligible articles were identified which offered telehealth solutions to promote the delivery and access to health care services for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the majority of these studies, the telehealth program was designed and implemented after the pandemic, indicating the potential of telehealth for promoting access to care and social distancing.

Our literature search identified 112 initial concepts, 26 unique concepts, 12 initial themes, and 4 final themes for opportunities along with 106 initial concepts, 37 unique concepts, 16 initial themes, and 6 final themes for challenges ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Final themes, unique concepts, and initial themes in opportunities and challenges domains extracted from studies applied telehealth for health care delivery in COVID-19 pandemic era.

| Final theme | Unique concept | Initial theme | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunities | Clinical ( n = 80) | Improved patient safety ( n = 36), improved physicians' safety ( n = 7), infection control ( n = 6), maintaining continuity of care ( n = 32), improved patient-centered care ( n = 6), better communication between patients and physicians ( n = 7), improving care effectiveness ( n = 23), improving care efficiency ( n = 17), improving quality of diagnosis ( n = 5), improving data quality ( n = 1) | Improved safety ( n = 40), maintaining continuity of care ( n = 32), improved patient-centered care ( n = 13), improved care quality ( n = 35) |

| Organizational ( n = 78) | Prevent hospitalization ( n = 9), reducing patients' admission in health care organization ( n = 7), improve patient and family satisfaction ( n = 56), improve provider satisfaction ( n = 18), cost reduction ( n = 14), cost saving ( n = 19), reduced travels expenses ( n = 7), timesaving ( n = 19), better management of institutional issues ( n = 3), improved organizational performance ( n = 5) | Reducing hospital workload ( n = 14), patient and provider satisfaction ( n = 52), cost saving ( n = 32, time saving ( n = 19), improved organizational performance ( n = 8) | |

| Technical ( n = 38) | Acceptance by providers and patients ( n = 21), usefulness ( n = 5), feasibility of telehealth ( n = 3), technology convenience ( n = 6), system ease of use ( n = 11) | Usefulness of telehealth ( n = 27), ease of use ( n = 17) | |

| Social ( n = 4) | Improving care equitability ( n = 4) | Care equitability ( n = 4) | |

| Challenges | Legal ( n = 17) | Privacy and confidentiality concerns ( n = 8), security concerns ( n = 1), accordance with institutional framework ( n = 4), lack of a regulatory framework ( n = 6) | Security, privacy and confidentiality concerns ( n = 8), regulations concerns ( n = 10) |

| Clinical ( n = 46) | Inability physical examination ( n = 30), patient evaluation concerns ( n = 4), limited personal contact ( n = 4), limited laboratory data ( n = 9), worsening clinical status ( n = 4), loss of care efficiency ( n = 2), concerns about accuracy drug administration ( n = 3), concern about diagnosis accuracy ( n = 1) | Clinical decision-making concerns ( n = 39), care efficiency concerns ( n = 10) | |

| Technical ( n = 41) | Connecting to network issues ( n = 29), initial set-up issues ( n = 3), device requirement issues ( n = 8), infrastructure issues ( n = 6) software problems ( n = 7), phone problems ( n = 2) | Connecting to network issues ( n = 30), technological problems ( n = 21), phone problems ( n = 2) | |

| Organizational ( n = 21) | Supporting issues ( n = 5), administrative issues ( n = 1), integration issues ( n = 1), team working ( n = 1), protocols and workflows ( n = 2), reduced productivity ( n = 2), time-consuming ( n = 6), scheduling issue ( n = 4), lack of knowledge/training ( n = 8) | Structure ( n = 6), Process ( n = 3), Managerial issues ( n = 15) | |

| Socio/financial ( n = 35) | Literacy gap ( n = 6), lack of computer skill and knowledge ( n = 5), social disparities ( n = 16), lack of confidence( n = 8), patient concerns ( n = 7), reimbursement concerns ( n = 8), billing issues ( n = 3) | Patient- related issues ( n = 11), Social disparities ( n = 16), confidence and concerns ( n = 15), reimbursement concerns, billing issues ( n = 11) | |

| Data quality ( n = 7) | Poor data quality ( n = 4), poor documentation ( n = 3) | Poor data quality ( n = 7) | |

The majority of the included articles were original study with 85 cases (76%), followed by case report ( n = 5, 4.46%) and commentary each with five articles (4.46%); letter to the editor, brief communication, and correspondence each with three articles (2.67%); case study and notes from field each with two articles (1.78%); and finally editorial, case series, clinical experience, and view point each with only one article.

Most of the studies used audiovisual media ( n = 85, 76%) for communication between health care practitioners and patients, followed by audio or phone call ( n = 21, 18.7%). The type of media was not specified in six studies ( Supplementary Appendix B , available in the online version).

The majority of the studies ( n = 85, 76%) implemented and applied telehealth during COVID-19 pandemic, while less than one-fourth of the studies ( n = 27, 24%) used telehealth before the pandemic and only advanced or promoted its use in this period ( Supplementary Appendix B , available in the online version).

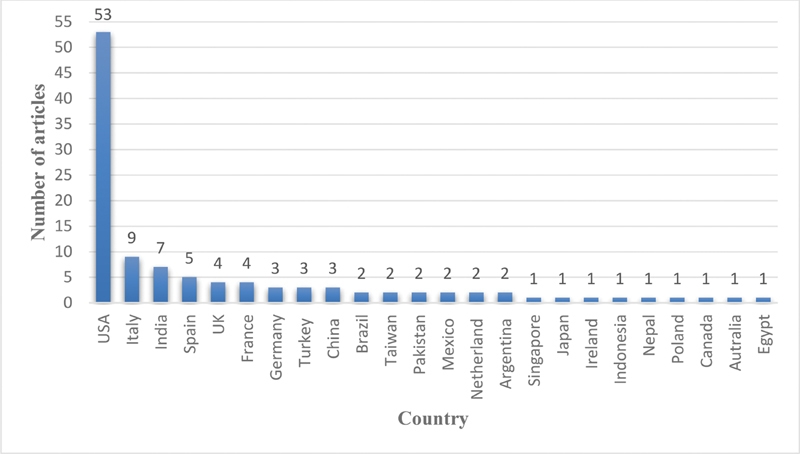

Distribution of Studies by Year and Country

All studies were published in 2020. The included studies were conducted in 24 countries, with almost half from the United States ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Country distribution of published articles.

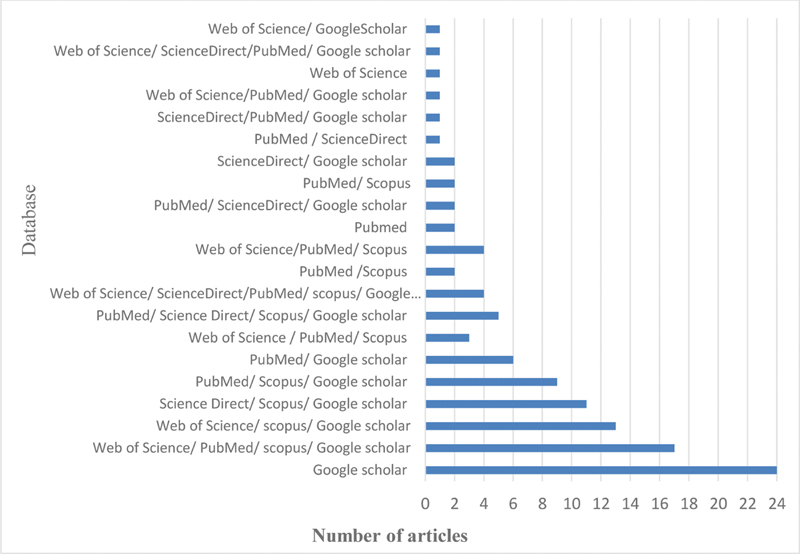

Distribution of Studies by Database

According to Fig. 3 , 86 of the studies (76.7%) included were identified by Google Scholar (with or without another search engine).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of articles by database sources.

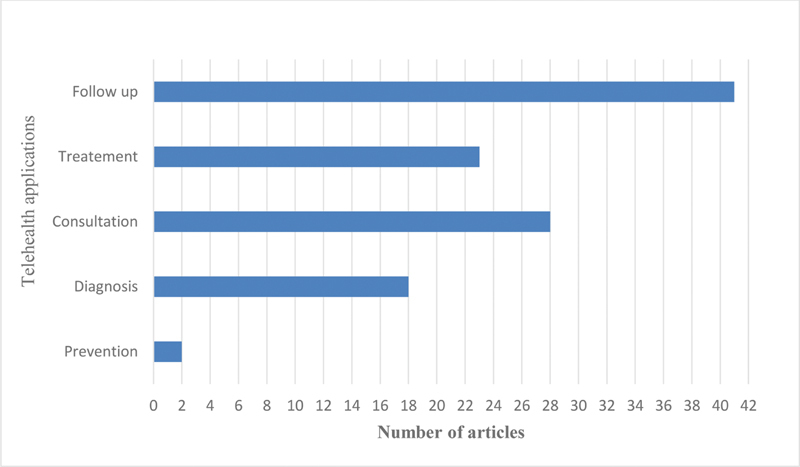

Distribution of Studies by Telehealth Application

In these studies, telehealth technologies were mostly used for patient follow-up ( n = 41, 36.6%) followed by consultation ( n = 28, 25%), treatment (prescription or others; n = 23, 20.5%), and diagnosis ( n = 18, 16%). Only two studies used telehealth for prevention purposes ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of articles by telehealth application.

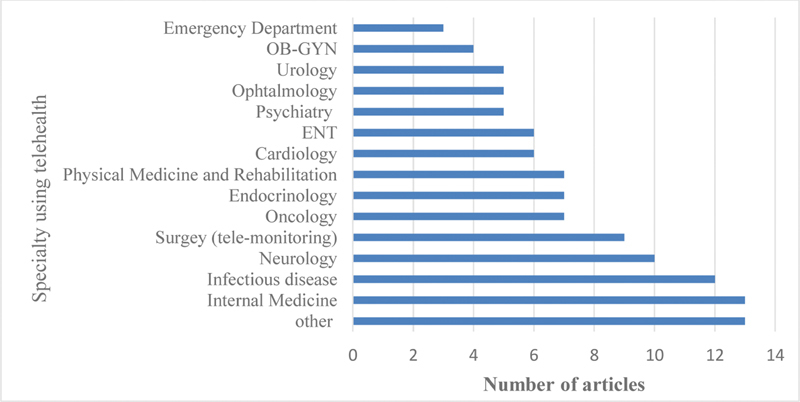

Distribution of Studies by Medical Specialty Using Telehealth

The specialties of internal medicine, oncology, and infectious diseases had the highest frequency of using telehealth technology during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of articles by medical specialty using telehealth synthesis of results. OB-GYN, obstetrics-gynecologist; ENT, ear–nose–tongue.

Distribution of Opportunities and Challenges

The findings of the thematic analysis are presented in Table 1 . The opportunities were classified into clinical, organizational, technical, and social opportunities. The challenges were categorized into six groups including legal, clinical, technical, organizational, socioeconomic, and data quality challenges. Table 1 shows the initial and unique concepts in addition to initial and final themes.

Clinical themes dealt with factors directly related to care delivery and technical ones included issues associated with any aspect of applying the technology. In addition, organizational themes were related to items organized and managed by HCOs, and sociofinancial themes included extraorganizational and human factors, as well as the factors affecting the financial performance and revenue of HCOs and insurers. Legal themes referred to challenges in dealing with regulation frameworks. Finally, data quality themes indicated challenges about data entry and documentation (for more details refer to Supplementary Appendices C and D , available in the online version).

Discussion

Four themes are extracted for opportunities and six for challenges of using telehealth in health care delivery during COVID-19 pandemic.

The clinical theme was most frequently identified across studies in both the opportunities and challenges domains. Regarding the clinical opportunities theme, improvement in patients' and health care workers' safety, care quality, pandemic management, and patient-centered care comprised the most common clinical initial themes. The initial themes were derived from concepts such as continuity of care, controlling pandemic, reducing the mortality rate, observing social distancing, and minimizing the exposure to COVID-19. Telehealth provides a basis for improving patient-centered care and enhancing the care effectiveness through facilitating access to care and the communication between patients and health care professionals, involving the patients in their own care process, and controlling their self-care. Telehealth technology is an effective approach to support a patient-centered care model which is highly encouraged due to improving patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and social wellbeing. 40

Numerous clinical challenges were reported in the reviewed studies, the most common of which was limited physical examination. Thus, the ideal telehealth cases are those where no examination or a limited examination (particularly visual or mental status examination) is sufficient.

Another critical aspect of the clinical challenge was care effectiveness. Although most of the studies have emphasized the effectiveness of care, four studies reported worsening of the patients' clinical opportunities which two studies performed in a similar environment. These studies were performed in neurology, urology, and adolescent field requiring more careful planning and face-to-face interaction. 40 41 42 43 44 Moreover, three other studies reported a challenging situation regarding drug administration. 27 45 46 Sudden tendency to deliver drugs using telehealth after an epidemic requires proper coordination and planning that in lack, drug administration will be problematic. It can be concluded that these challenges are related to the study setting, context, and monitoring of medication administration. Besides, designing appropriate electronic forms and interfaces for timely and accurate recording of related data would increase the data and documentation quality.

Regarding technical opportunities, the usefulness of telehealth from the patients and providers' perspectives was the most common technological opportunities acknowledged in the included articles, followed by ease of use and agility of technology. Perceived convenience and time- or cost saving are key components in the usefulness of telehealth technology. The intention to adopt telehealth technology is influenced by its perceived usefulness and ease of use by users. Telehealth technology agility supports collaborative organizations and plays a key role in facilitating collaborative care. 47 Collaborative care using telehealth modalities provides a safe solution to meet the different needs of patients and help control the COVID-19 pandemic. 48

Regarding technical challenges, the most important concept was the internet access or data transmission, especially in video-based visits, which was mostly reported by patients. This problem prevents visits from occurring or leads to incomplete visits or changes from video to audio or phone. 44 49 Another challenge was the initial set up of the program due to the time pressure caused by the critical situation, lack of previous experience, and lack of integrated electronic medical records (EMRs). The concept of patient access to equipment and experience required to use the system also included issues related to lack of infrastructure and technology use which worsened the gap in telehealth acceptance and usage.

Users' and providers' satisfaction, as the most common organizational opportunity, is a key indicator of the success of each modality of telehealth technology, indicating that the users' expectations have been met. 50 Eliminating the need for travel and saving time and money, ease of access to telehealth services, 51 and observance of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic can be the main reasons for users' satisfaction. Telehealth could reduce hospital admission and workload by providing necessary services for patients and reducing the time and costs. Furthermore, telehealth can improve staff efficiency by automating tasks, saving staff's time, and facilitating access to practitioners.

HCOs have faced numerous organizational challenges in implementing telehealth in the current pandemic crisis. Many do not have a history of the widespread use of telehealth; as a result, they use it without proper knowledge and training of the staff and patients, 52 imposing a host of organizational challenges. Resolving some of these challenges requires structural changes to apply a new approach to care delivery and integration with work patterns to decrease the staff load. 49 53 54 Managerial challenges also deal with spending more time, scheduling patients, and providing the necessary training.

Social issues were the most challenging findings of this study. While four studies reported an increase in equitability as a significant consequence of using telehealth, other studies identified social differences (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and income) as challenges in equitable access to the effective and widespread use of this modality. On the one hand, telehealth has the potential to ensure access to health care in disadvantaged areas by removing the barrier of distance and meeting the needs of diverse patients. On the other hand, social challenges are related to the equitable access of all subpopulations of the society to telehealth services. Different groups of people have large differences in terms of technology literacy, language, income, and level of trust in technology which affects their ability to use telehealth. 44 49 The importance of these factors is such that they lead to a dramatic increase in inequities in access to care. Of course, with continued use, most users gain the knowledge and experience needed to work with the system 27 and develop trust in the technology by understanding its benefits. However, reducing or eliminating barriers, such as digital literacy gaps, access requirements, and regulation amendments to the use of telehealth for providing care for different patient populations could further improve equity in health care.

Economic issues were challenging for both providers and patients. While reimbursement is one of the most vital factors in physicians' willingness to provide telehealth services, 55 it does not exist or is negligible in many countries. However, in countries with approved regulations, full reimbursement is calculated for video-based visits, and only in the latest editions of the regulations have telephone visits been reimbursed by some payers. 56 On the other hand, in the absence of reimbursement, paying the visit fee is a serious concern of the patients 57 which is exacerbated by economic conditions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Legal issues mainly resulted from the special situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. They have challenged many regulatory frameworks for the provision of care. It is always essential to maintain a balance between security/privacy issues and access to care. Free platforms were used in several included studies; however, although they improved access to care, they raised serious regulatory concerns. In this regard, some countries have reduced or facilitated the requirements for telehealth services. 22 58 These concerns are also observed in countries with no confirmed legal frameworks for the use of telehealth. 52 The technical solutions include using compliant applications, applying corporate accounts, and using the latest versions of the applications. 59 Furthermore, applying instructions related to the information exchange management, such as using yes/no questions, is another solution to legal challenges. 60

Limitations

The first limitation of this study was that it covered the opportunities and challenges of using telehealth in the COVID-19 era reported in the included articles published until November 4, 2020. As a result, the opportunities and challenges may not be comprehensive. The second limitation was that this review was narrowed to English language studies, and therefore some local or national opportunities and challenges could have been missed. Therefore, national and regional studies should be conducted to identify the opportunities and challenges regarding the use of telehealth technology for better management and control of disasters and public health emergencies.

Conclusion

Clinical, organizational, technical, and social themes were the primary opportunities of using telehealth during the pandemic. Furthermore, legal, clinical, organizational, technical, and socioeconomic themes were the main challenges of applying telehealth in the pandemic era. Telehealth has a great potential in providing collaborative and patient-centered care, thus improving the satisfaction of patients and health care providers. Despite the favorable results of using telehealth, attention should be paid to the barriers to its successful use. This study provides valuable information about the opportunities and challenges of implementing telehealth to policy makers for offering safe, efficient, accessible health care delivery to diverse patient populations during and after the COVID-19 pandemic era so that they can make more informed decisions about implementing telehealth in response to the situation by addressing the barriers ahead.

Clinical Relevance Statements

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in challenges related to delivery of care in the health care industry.

Application of telehealth in the health care industry has improved the safety of the patients and staff, care quality, pandemic management, and patient-centered care; however, its use is associated with some challenges including inability to perform physical examination, security issues, and legal and social challenges.

COVID-19 pandemic has significantly accelerated the use of telehealth across the world.

Knowledge of the practical opportunities and challenges associated with the use of telehealth will improve effective policies regarding the use of telehealth in managing this pandemic.

Multiple Choice Questions

-

Which specialty has the highest frequency of using telehealth technology during the COVID-19 pandemic?

internal medicine

infectious disease

oncology

ENT

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option a. According to Fig. 5 , in 13 studies, internal medicine specialists published the results of the use of telehealth in COVID-19 pandemic.

-

What is the most important concept regarding the technical challenges?

internet access or data transmission

initial set up of the program

device requirement issues

infrastructure issues to lack of infrastructure

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option a. Regarding technical challenges, the most important concept was the internet access or data transmission, especially in video-based visits, which was mostly reported by patients.

-

What theme is the most challenging findings of this study?

social

technical

legal

clinical

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option a. Social issues were the most challenging findings of this study. While four studies reported an increase in equitability as a significant consequence of using telehealth, other studies identified social differences (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and income) as challenges in equitable access to the effective and widespread use of this modality.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

No human subjects were involved in the project.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ficarra V, Novara G, Abrate A. Urology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva urologica e nefrologica. Italian J Urol Nephrol. 2020;72(03):369–375. doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green B N, Pence T V, Kwan L, Rokicki-Parashar J. Rapid deployment of chiropractic telehealth at 2 worksite health centers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: observations from the field. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(05):4040–4.04E12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fieux M, Duret S, Bawazeer N, Denoix L, Zaouche S, Tringali S. Telemedicine for ENT: effect on quality of care during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137(04):257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinzerling A, Stuckey M J, Scheuer T. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient - Solano County, California, February 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):472–476. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Z, Zhuang D, Xiong B, Deng D X, Li H, Lai W. Occupational exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in burns treatment during the COVID-19 epidemic: specific diagnosis and treatment protocol. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abuzeineh M, Muzaale A D, Crews D C. Telemedicine in the care of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019: case reports. Transplant Proc. 2020;52(09):2620–2625. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowe T A, Patel M, O'Conor R, McMackin S, Hoak V, Lindquist L A. COVID-19 exposures and infection control among home care agencies. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104214. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contreras C M, Metzger G A, Beane J D, Dedhia P H, Ejaz A, Pawlik T M. Telemedicine: patient-provider clinical engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24(07):1692–1697. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McSwain S D, Bernard J, Burke B L., Jr American Telemedicine Association operating procedures for pediatric telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23(09):699–706. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George L A, Cross R K. Telemedicine in gastroenterology in the wake of COVID-19. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(11):1013–1015. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1806056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Research Urology Network (RUN) . Novara G, Checcucci E, Crestani A. Telehealth in urology: a systematic review of the literature. How much can telemedicine be useful during and after the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur Urol. 2020;78(06):786–811. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linz D, Pluymaekers N A, Hendriks J M. TeleCheck-AF for COVID-19: a European mHealth project to facilitate atrial fibrillation management through teleconsultation during COVID19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(21):1954–1955. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Hara V M, Johnston S V, Browne N T. The paediatric weight management office visit via telemedicine: pre- to post-COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Obes. 2020;15(08):e12694. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters A L, Garg S K. The silver lining to COVID-19: avoiding diabetic ketoacidosis admissions with telehealth. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(06):449–453. doi: 10.1089/dia.2020.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salzano A, D'Assante R, Stagnaro F M. Heart failure management during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: a telemedicine experience from a heart failure university tertiary referral centre. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(06):1048–1050. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann D M, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa P A, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(07):1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grange E S, Neil E J, Stoffel M. Responding to COVID-19: the UW medicine information technology services experience. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(02):265–275. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sell N M, Silver J K, Rando S, Draviam A C, Mina D S, Qadan M. Prehabilitation telemedicine in neoadjuvant surgical oncology patients during the Novel COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020;272(02):e81–e83. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cilia R, Mancini F, Bloem B R, Eleopra R. Telemedicine for parkinsonism: a two-step model based on the COVID-19 experience in Milan, Italy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;75:130–132. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compton M, Soper M, Reilly B. A feasibility study of urgent implementation of cystic fibrosis multidisciplinary telemedicine clinic in the face of COVID-19 pandemic: single-center experience. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(08):978–984. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal E M, Alwan L, Pitney C. Establishing clinical pharmacist telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(17):1403–1408. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atreya S, Kumar G, Samal J.Patients'/Caregivers' perspectives on telemedicine service for advanced cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory survey Indian J Palliat Care 202026(5, suppl 1):S40–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewitt K C, Loring D W.Emory university telehealth neuropsychology development and implementation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic Clin Neuropsychol 202034(7,8):1352–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurrasse S E, Rastatter J C, Hoff S R, Billings K R, Valika T S. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: a pediatric otolaryngology perspective. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(03):480–481. doi: 10.1177/0194599820931827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qualliotine J R, Orosco R K. Self-removing passive drain to facilitate postoperative care via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(06):1305–1307. doi: 10.1002/hed.26203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivatana V, Liu F, Levine D M, Kalloo S D.Early Use of Telehealth in Home Dialysis During the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York CityKidney2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Esper R B, da Silva R S, Oikawa F TC.Empirical treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for suspected cases of COVID-19 followed-up by telemedicineAccessed July 30, 2021 at:https://pgibertie.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/2020.04.15-journal-manuscript-final.pdf

- 28.Guest J L, Sullivan P S, Valentine-Graves M. Suitability and sufficiency of telehealth clinician-observed, participant-collected samples for SARS-CoV-2 testing: the iCollect cohort pilot study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(02):e19731. doi: 10.2196/19731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruni T, Lalvani A, Richeldi L. Telemedicine-enabled accelerated discharge of hospitalized COVID-19 patients to isolation in repurposed hotel rooms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(04):508–510. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1238OE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon W J, Henderson D, DeSharone A. Remote patient monitoring program for hospital discharged COVID-19 patients. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(05):792–801. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grönqvist H, Olsson E MG, Johansson B. Fifteen challenges in establishing a multidisciplinary research program on eHealth research in a university setting: a case study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(05):e173. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldonado J MSV, Marques A, Cruz A.Telemedicine: challenges to dissemination in Brazil Cadernos de saude publica 201632(Suppl 02) 10.1590/0102-311x00155615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Heuvel J F, Groenhof T K, Veerbeek J H. eHealth as the next-generation perinatal care: an overview of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(06):e202. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.PRISMA-P Group . Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(01):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong Q N, Pluye P, Fàbregues S. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:49–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.AMA Physician Specialty Groups and CodesAccessed 22 April, 2021 at:https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/178504/file-2553042497-pdf/documents/AMA_Physician_Specialty_Codes.pdf?t=1425245957165

- 37.Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K.Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventionsAccessed July 30, 2021 at:https://www.integrate-hta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Guidance-on-choosing-qualitative-evidence-synthesis-methods-for-use-in-HTA-of-complex-interventions.pdf

- 38.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(45):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas P J, Baird J, Arai L, Law C, Roberts H M. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuipers S J, Cramm J M, Nieboer A P. The importance of patient-centered care and co-creation of care for satisfaction with care and physical and social well-being of patients with multi-morbidity in the primary care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(01):13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capozzo R, Zoccolella S, Frisullo M E. Telemedicine for delivery of care in frontotemporal lobar degeneration during COVID-19 pandemic: results from Southern Italy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(02):481–489. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capozzo R, Zoccolella S, Musio M, Barone R, Accogli M, Logroscino G.Telemedicine is a useful tool to deliver care to patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic: results from Southern Italy Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 202021(7,8):542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leibar Tamayo A, Linares Espinós E, Ríos González E. Evaluation of teleconsultation system in the urological patient during the COVID-19 pandemic [in Spanish] Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed) 2020;44(09):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood S M, White K, Peebles R. Outcomes of a rapid adolescent telehealth scale-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(02):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esper G J, Sweeney R L, Winchell E. Rapid systemwide implementation of outpatient telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Healthc Manag. 2020;65(06):443–452. doi: 10.1097/JHM-D-20-00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Wrede R, Moskau-Hartmann S, Baumgartner T, Helmstaedter C, Surges R. Counseling of people with epilepsy via telemedicine: experiences at a German tertiary epilepsy center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107298. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benaben F, Vernadat F B. Information System agility to support collaborative organisations. Enterprise Inf Syst. 2017;11(04):470–473. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vervoort D, Ma X, Luc J GY. COVID-19 pandemic: a time for collaboration and a unified global health front. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33(01):mzaa065. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rametta S C, Fridinger S E, Gonzalez A K. Analyzing 2,589 child neurology telehealth encounters necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020;95(09):e1257–e1266. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruse C S, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(08):e016242–e016242. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orlando J F, Beard M, Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers' satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients' health. PLoS One. 2019;14(08):e0221848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Runfola M, Fantola G, Pintus S, Iafrancesco M, Moroni R. Telemedicine implementation on a bariatric outpatient clinic during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: an unexpected hill-start. Obes Surg. 2020;30(12):5145–5149. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-05007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martínez-García M, Bal-Alvarado M, Santos Guerra F. Tracing of COVID-19 patients by telemedicine with telemonitoring. Rev Clin Espanol. 2020;220(08) doi: 10.1016/j.rceng.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smrke A, Younger E, Wilson R. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact on care for rare cancers. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1046–1051. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tenforde A S, Borgstrom H, Polich G. Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: a survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(11):977–981. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eberly L A, Khatana S AM, Nathan A S. Telemedicine outpatient cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic: bridging or opening the digital divide? Circulation. 2020;142(05):510–512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serper M, Nunes F, Ahmad N, Roberts D, Metz D C, Mehta S J. Positive early patient and clinician experience with telemedicine in an academic gastroenterology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(04):1589–1591. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobrusin A, Hawa F, Gladshteyn M. Gastroenterologists and patients report high satisfaction rates with telehealth services during the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2393–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee A KF, Cho R HW, Lau E HL. Mitigation of head and neck cancer service disruption during COVID-19 in Hong Kong through telehealth and multi-institutional collaboration. Head Neck. 2020;42(07):1454–1459. doi: 10.1002/hed.26226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barney A, Buckelew S, Mesheriakova V, Raymond-Flesch M. The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: challenges and opportunities for innovation. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(02):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahsan M F, Irshad A, Malik K. Patient satisfaction at telemedicine center in COVID-19 pandemic-Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University, (Szabmu) Islamabad. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal. 2020;70(02):S578–S583. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Álvarez-Maestro M, de Castro Guerín C, Fernández-Pascual E. Evaluation of teleconsultation system in the urological patient during the COVID-19 pandemic [in Spanish] 2020;44(09):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashraf J, Aqeel I. Efficacy of telemedicine to manage heart failure patients during COVID-19 lockdown. Biomedica. 2020;36:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ashry A H, Alsawy M F. Doctor-patient distancing: an early experience of telemedicine for postoperative neurosurgical care in the time of COVID-19. Egypt J Neurol Psychiat Neurosurg. 2020;56(01):80. doi: 10.1186/s41983-020-00212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Badiee R K, Willsher H, Rorison E. Transitioning multidisciplinary craniofacial care to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center experience. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(09):e3143. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhuva S, Lankford C, Patel N, Haddas R. Implementation and patient satisfaction of telemedicine in spine physical medicine and rehabilitation patients during the COVID-19 shutdown. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(12):1079–1085. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boehm K, Ziewers S, Brandt M P. Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic-potential, risk factors, and patients' perspective. Eur Urol. 2020;78(01):16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bourdon H, Jaillant R, Ballino A. Teleconsultation in primary ophthalmic emergencies during the COVID-19 lockdown in Paris: experience with 500 patients in March and April 2020. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020;43(07):577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burgos L M, Benzadón M, Candiello A. Telehealth in heart failure care during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Argentina. International Journal of Heart Failure. 2020;2(04):247–253. doi: 10.36628/ijhf.2020.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carlberg D J, Bhat R, Patterson W O. Preliminary assessment of a telehealth approach to evaluating, treating, and discharging low-acuity patients with suspected COVID-19. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(06):957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casares M, Wombles C, Skinner H J, Westerveld M, Gireesh E D. Telehealth perceptions in patients with epilepsy and providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107394. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang J H, Diop M, Burgos Y L. Telehealth in outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients during COVID-19 pandemic in New York. Letter Clin Transplant. 2020;34(12):e14097. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chávarri-Guerra Y, Ramos-López W A, Covarrubias-Gómez A. Providing supportive and palliative care using telemedicine for patients with advanced cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Oncologist. 2021;26(03):e512–e515. doi: 10.1002/onco.13568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colle R, Ait Tayeb A EK, de Larminat D. Short-term acceptability by patients and psychiatrists of the turn to psychiatric teleconsultation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(08):443–444. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Darcourt J G, Aparicio K, Dorsey P M.Analysis of the implementation of telehealth visits for care of patients with cancer in houston during the COVID-19 pandemicJCO Oncol Pract2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Davis C, Novak M, Patel A, Davis C, Fitzwater R, Hale N. The COVID-19 catalyst: analysis of a tertiary academic institution's rapid assimilation of telemedicine. Urol Pract. 2020;7(04):247–251. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deshmukh A V, Badakere A, Sheth J, Bhate M, Kulkarni S, Kekunnaya R. Pivoting to teleconsultation for paediatric ophthalmology and strabismus: our experience during COVID-19 times. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(07):1387–1391. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1675_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Efe C, Simşek C, Batıbay E, Calışkan A R, Wahlin S. Feasibility of telehealth in the management of autoimmune hepatitis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(12):1215–1219. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1822734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Evin F, Er E, Ata A. The value of telemedicine for the follow-up of patients with new onset type 1 diabetes mellitus during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: a report of eight cases. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2020.2020.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Exum E, Hull B L, Lee A CW, Gumieny A, Villarreal C, Longnecker D. Applying telehealth technologies and strategies to provide acute care consultation and treatment of patients with confirmed or possible COVID-19. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2020;11(03):103–112. doi: 10.1097/JAT.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Futterman I, Rosenfeld E, Toaff M. Addressing disparities in prenatal care via telehealth during COVID-19: prenatal satisfaction survey in East Harlem. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38(05):89–92. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1718695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goodman-Casanova J M, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F. Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(05):e19434. doi: 10.2196/19434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Govil N, Raol N, Tey C S, Goudy S L, Alfonso K P. Rapid telemedicine implementation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in an academic pediatric otolaryngology practice. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;139:110447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grutters L A, Majoor K I, Mattern E SK, Hardeman J A, van Swol C FP, Vorselaars A DM. Home telemonitoring makes early hospital discharge of COVID-19 patients possible. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1825–1827. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guarino M, Cossiga V, Fiorentino A, Pontillo G, Morisco F. Use of telemedicine for chronic liver disease at a single care center during the COVID-19 pandemic: prospective observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(09):e20874. doi: 10.2196/20874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hoagland B, Torres T S, Bezerra D RB. Telemedicine as a tool for PrEP delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic in a large HIV prevention service in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Brazil J Infect Dis. 2020;24(04):360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joshi A U, Lewiss R E, Aini M, Babula B, Henwood P C. Solving community SARS-CoV-2 testing with telehealth: development and implementation for screening, evaluation and testing. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(10):e20419. doi: 10.2196/20419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kang S, Thomas P BM, Sim D A, Parker R T, Daniel C, Uddin J M. Oculoplastic video-based telemedicine consultations: COVID-19 and beyond. Eye (Lond) 2020;34(07):1193–1195. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-0953-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kerber A A, Soma D B, Youssef M J. Chilblains-like dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19 diagnosed by serology via multidisciplinary virtual care. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(08):1024–1025. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khairat S, Pillai M, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Evaluating the telehealth experience of patients with COVID-19 symptoms: recommendations on best practices. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(05):665–672. doi: 10.1177/2374373520952975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klain M, Nappi C, Maurea S. Management of differentiated thyroid cancer through nuclear medicine facilities during Covid-19 emergency: the telemedicine challenge. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(03):831–836. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krenitsky N M, Spiegelman J, Sutton D, Syeda S, Moroz L. Primed for a pandemic: Implementation of telehealth outpatient monitoring for women with mild COVID-19. Semin Perinatol. 2020;44(07):151285. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2020.151285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lai FH-y, Yan E W, Yu KK-y, Tsui W-S, Chan D T, Yee B K. The protective impact of telemedicine on persons with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(11):1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Layfield E, Triantafillou V, Prasad A. Telemedicine for head and neck ambulatory visits during COVID-19: evaluating usability and patient satisfaction. Head Neck. 2020;42(07):1681–1689. doi: 10.1002/hed.26285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li H L, Chan Y C, Huang J X, Cheng S W. Pilot study using telemedicine video consultation for vascular patients' care during the COVID-19 period. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;68:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lim S T, Yap F, Chin X. Bridging the needs of adolescent diabetes care during COVID-19: a nurse-led telehealth initiative. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(04):615–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin C H, Tseng W P, Wu J L. A double triage and telemedicine protocol to optimize infection control in an emergency department in Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(06):e20586. doi: 10.2196/20586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lonergan P E, Washington Iii S L, Branagan L. Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(07):e19322. doi: 10.2196/19322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Longo M, Caruso P, Petrizzo M. Glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes using a hybrid closed loop system and followed by telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;169:108440. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lopez-Villegas A, Maroto-Martin S, Baena-Lopez M A. Telemedicine in times of the pandemic produced by COVID-19: implementation of a teleconsultation protocol in a hospital emergency department. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8(04):357. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lynch D A, Medalia A, Saperstein A. The design, implementation, and acceptability of a telehealth comprehensive recovery service for people with complex psychosis living in NYC during the COVID-19 crisis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:581149. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Madden N, Emeruwa U N, Friedman A M. Telehealth uptake into prenatal care and provider attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(10):1005–1014. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mgbako O, Miller E H, Santoro A F. COVID-19, telemedicine, and patient empowerment in HIV care and research. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(07):1990–1993. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02926-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mittal A, Singh A P, Sureka B, Singh K, Pareek P, Misra S. Telemedicine during COVID-19 crisis in resource poor districts near Indo-Pak border of western Rajasthan. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(07):3789–3790. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1041_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miu A S, Vo H T, Palka J M, Glowacki C R, Robinson R J. Teletherapy with serious mental illness populations during COVID-19: telehealth conversion and engagement. Couns Psychol Q. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1791800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morisada M V, Hwang J, Gill A S, Wilson M D, Strong E B, Steele T O. Telemedicine, patient satisfaction, and chronic rhinosinusitis care in the era of COVID-19. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2021;35(06):984–990. doi: 10.1177/1945892420970460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nakagawa K, Umazume T, Mayama M. Feasibility and safety of urgently initiated maternal telemedicine in response to the spread of COVID-19: a 1-month report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(10):1967–1971. doi: 10.1111/jog.14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.O'Donovan M, Buckley C, Benson J. Telehealth for delivery of haemophilia comprehensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Haemophilia. 2020;26(06):984–990. doi: 10.1111/hae.14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Panda P K, Dawman L, Panda P, Sharawat I K. Feasibility and effectiveness of teleconsultation in children with epilepsy amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in a resource-limited country. Seizure. 2020;81:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pandey N, Srivastava R M, Kumar G, Katiyar V, Agrawal S. Teleconsultation at a tertiary care government medical university during COVID-19 Lockdown in India - a pilot study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(07):1381–1384. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1658_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Patel S, Hamdan S, Donahue S. Optimising telemedicine in ophthalmology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1357633X20949796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pinar U, Anract J, Perrot O. Preliminary assessment of patient and physician satisfaction with the use of teleconsultation in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Urol. 2020;39(06):1991–1996. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03432-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pinzon R, Paramitha D, Wijaya V O. Acceleration of telemedicine use for chronic neurological disease patients during covid-19 pandemic in yogyakarta, Indonesia: A case series study. Kesmas. 2020;15(02):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Poudyal B S, Gyawali B, Rondelli D. Rapidly established telehealth care for blood cancer patients in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic using the free app Viber. E Cancer Med Sci. 2020;14:ed104. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.ed104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Quinn L, Macpherson C, Long K, Shah H. Promoting physical activity via telehealth in people with Parkinson disease: the path forward after the COVID-19 pandemic? Phys Ther. 2020;100(10):1730–1736. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peden C J, Mohan S, Pagán V. Telemedicine and COVID-19: an observational study of rapid scale up in a US academic medical system. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(09):2823–2825. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05917-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Perez-Alba E, Nuzzolo-Shihadeh L, Espinosa-Mora J E, Camacho-Ortiz A. Use of self-administered surveys through QR code and same center telemedicine in a walk-in clinic in the era of COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(06):985–986. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rabuñal R, Suarez-Gil R, Golpe R. Usefulness of a telemedicine tool TELEA in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(11):1332–1335. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rahman S, Speed T, Xie A, Shecter R, Hanna M N. Perioperative pain management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a telemedicine approach. Pain Med. 2020;22(01):3–6. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ramaswamy A, Yu M, Drangsholt S. Patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(09):e20786. doi: 10.2196/20786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ratliff C R, Shifflett R, Howell A, Kennedy C. Telehealth for wound management during the COVID-19 pandemic: case studies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2020;47(05):445–449. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ratwani R M, Brennan D, Sheahan W. A descriptive analysis of an on-demand telehealth approach for remote COVID-19 patient screening. J Telemed Telecare. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1357633X20943339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Reardon J, Yuen J, Lim T, Ng R, Gobis B. Provision of virtual outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: enabling factors and experiences from the UBC pharmacists clinic. Innov Pharm. 2020;11(04):7–7. doi: 10.24926/iip.v11i4.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rogers B G, Coats C S, Adams E. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ+ clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, providence, RI. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2743–2747. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02895-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ryu W HA, Kerolus M G, Traynelis V C. Clinicians' user experience of telemedicine in neurosurgery during COVID-19. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:e359–e367. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.10.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Santonicola A, Zingone F, Camera S, Siniscalchi M, Ciacci C. Telemedicine in the COVID-19 era for Liver Transplant Recipients: an Italian lockdown area experience. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;45(03):101508. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sasangohar F, Bradshaw M R, Carlson M M. Adapting an outpatient psychiatric clinic to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a practice perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e22523. doi: 10.2196/22523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Satin A M, Shenoy K, Sheha E D. Spine patient satisfaction with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Global Spine J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2192568220965521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Semprino M, Fasulo L, Fortini S. Telemedicine, drug-resistant epilepsy, and ketogenic dietary therapies: a patient survey of a pediatric remote-care program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107493. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Shawar R S, Cymbaluk A L, Bell J J. Isolation and education during a pandemic: novel telehealth approach to family education for a child with new-onset type 1 diabetes and concomitant COVID-19. Clin Diabetes. 2021;39(01):124–127. doi: 10.2337/cd20-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shenoy P, Ahmed S, Paul A, Skaria T G, Joby J, Alias B. Switching to teleconsultation for rheumatology in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: feasibility and patient response in India. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(09):2757–2762. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Shur N, Atabaki S M, Kisling M S. Rapid deployment of a telemedicine care model for genetics and metabolism during COVID-19. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185(01):68–72. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Singh G, Kapoor S, Bansal V. Active surveillance with telemedicine in patients on anticoagulants during the national lockdown (COVID-19 phase) and comparison with pre-COVID-19 phase. Egypt Heart J. 2020;72(01):70. doi: 10.1186/s43044-020-00105-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Somani B K, Pietropaolo A, Coulter P, Smith J. Delivery of urological services (telemedicine and urgent surgery) during COVID-19 lockdown: experience and lessons learnt from a university hospital in United Kingdom. Scott Med J. 2020;65(04):109–111. doi: 10.1177/0036933020951932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Świerad M, Dyrbuś K, Szkodziński J, Zembala M O, Kalarus Z, Gąsior M.Telehealth visits in a tertiary cardiovascular center as a response of the healthcare system to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in Poland Pol Arch Intern Med 2020130(7,8):700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tenforde A S, Iaccarino M A, Borgstrom H. Feasibility and high quality measured in the rapid expansion of telemedicine during COVID-19 for sports and musculoskeletal medicine practice. PM R. 2020 doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Thomas I, Siew L QC, Rutkowski K. Synchronous telemedicine in allergy: lessons learned and transformation of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;9(01):170–176e.1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Torrente-Rodríguez R M, Lukas H, Tu J. SARS-CoV-2 RapidPlex: a graphene-based multiplexed telemedicine platform for rapid and low-cost COVID-19 diagnosis and monitoring. Matter. 2020;3(06):1981–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2020.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.van der Velden R MJ, Hermans A NL, Pluymaekers N AHA.Coordination of a remote mHealth infrastructure for atrial fibrillation management during COVID-19 and beyond: TeleCheck-AF Int J Care Coord 202023(2,3):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Vasta R, Moglia C, D'Ovidio F.Telemedicine for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic: an Italian ALS referral center experience Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 202022(3,4):308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Willems L M, Balcik Y, Noda A H. SARS-CoV-2-related rapid reorganization of an epilepsy outpatient clinic from personal appointments to telemedicine services: a German single-center experience. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107483. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wootton S L, King M, Alison J A, Mahadev S, Chan A SL. COVID-19 rehabilitation delivered via a telehealth pulmonary rehabilitation model: a case series. Respirol Case Rep. 2020;8(08):e00669. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wu Y R, Chou T J, Wang Y J. Smartphone-enabled, telehealth-based family conferences in palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: pilot observational study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(10):e22069. doi: 10.2196/22069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Xu H, Huang S, Qiu C. Monitoring and management of home-quarantined Patients With COVID-19 Using a WeChat-based telemedicine system: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(07):e19514. doi: 10.2196/19514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yildiz F, Oksuzoglu B. Teleoncology or telemedicine for oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: the new normal for breast cancer survivors? Future Oncol. 2020;16(28):2191–2195. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yoon E J, Tong D, Anton G M. Patient satisfaction with neurosurgery telemedicine visits during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. World Neurosurg. 2020;145:e184–e191. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.09.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zhu C, Williamson J, Lin A. Implications for telemedicine for surgery patients after COVID-19: survey of patient and provider experiences. Am Surg. 2020;86(08):907–915. doi: 10.1177/0003134820945196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zimmerman B S, Seidman D, Berger N. Patient perception of telehealth services for breast and gynecologic oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center survey-based study. J Breast Cancer. 2020;23(05):542–552. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2020.23.e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bains J, Greenwald P W, Mulcare M R. Utilizing telemedicine in a novel approach to COVID-19 management and patient experience in the emergency department. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(03):254–260. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Tenforde A S, Iaccarino M A, Borgstrom H. Telemedicine during COVID-19 for outpatient sports and musculoskeletal medicine physicians. PM R. 2020;12(09):926–932. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.