Abstract

Objective:

Validate a conceptual framework and identify pathways between antecedent (life-course socioeconomic status (L-SES)), predisposing (age, sex, married, homeless as a child), enabling (health literacy, acculturation), and need (disability) social determinants of health (SDoH) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) in US immigrants.

Methods:

181 immigrants were enrolled in the study. Path analysis was used to identify paths by which SDoH influence SBP and to determine if antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors have direct and indirect relationships with SBP.

Results:

The final model(chi2(5)=14.88, p=0.011, RMSEA=0.070, pclose=0.17, CFI=0.96) showed L-SES was directly associated with age(0.12,p=0.019) and disability(0.17,p=0.001); and indirectly associated with disability(0.29,p<0.001) and SBP(0.31,p<0.001). Age(0.31, p<0.001) and sex(0.25,p<0.001) were directly associated with SBP, and age was directly associated with disability(0.29,p<0.001) and indirectly associated with SBP(0.14,p=0.018). Other predisposing factors such as being married(−0.32,p<0.001) and being homeless as a child alone (0.16,p<0.001) were directly associated with disability and indirectly associated(0.14,p=0.018) with SBP. Enabling factor of health literacy(0.16,p=0.001) was directly associated with disability and indirectly associated(0.14,p=0.018) with SBP. Need factor of disability(0.14,p=0.018) was directly associated with SBP.

Conclusions:

This study provides the first validation of a conceptual model for the relationship between SDoH and SBP among immigrants and identifies potential targets for focused interventions.

Keywords: social determinants, immigrant, blood pressure

Introduction

High blood pressure, a highly burdensome condition globally, accounts for more than 9 million deaths worldwide and is a key risk factors for mortality and morbidity in the United States [1]. For example, approximately 1000 deaths in the US each day are attributed to hypertension and almost three-quarters of individuals who have their first stroke or heart attack, and those with heart failure often have high blood pressure [2]. In addition, hypertension imposes an enormous financial burden on the US with an estimated $112 billion in medical costs in 2015 which is expected to increase to $261 billion in the next 15 years [3].

Hypertension is of particular concern in foreign-born populations residing in the US, which totaled approximately 13% of the US population in 2018 [4]. Research shows that newer immigrants, i.e. those who reside in the US for less than ten years, often have lower prevalence of hypertension compared to the US-born population [5–10]. It has also been found that mean blood pressure increases among foreign-born individuals as length of residence increases, often surpassing levels of the native population [5–10]. While biological and genetic differences have been identified between native-born and some immigrant groups, there is a growing recognition of the role of social determinants in outcomes related to chronic diseases, such as hypertension. [7; 11; 12]. Meanwhile, social determinants of health, or factors including where one was born, lived, worked, or grew up, are known to influence health and often explain differences seen in health outcomes [13–15]. Social determinants, such as culture and lifestyle, vary between US-born and immigrants due to country of birth or region of origin and may explain differences seen in the prevalence of hypertension [11, 16]. Immigrants have different social determinants that influence health outcomes that differ from those commonly associated with native-born population, such as limited English proficiency, poverty, stress, low educational attainment, social isolation, minimal or no access to health care, inability to qualify for insurance due to legal status, and high disease burden [5, 17–19].

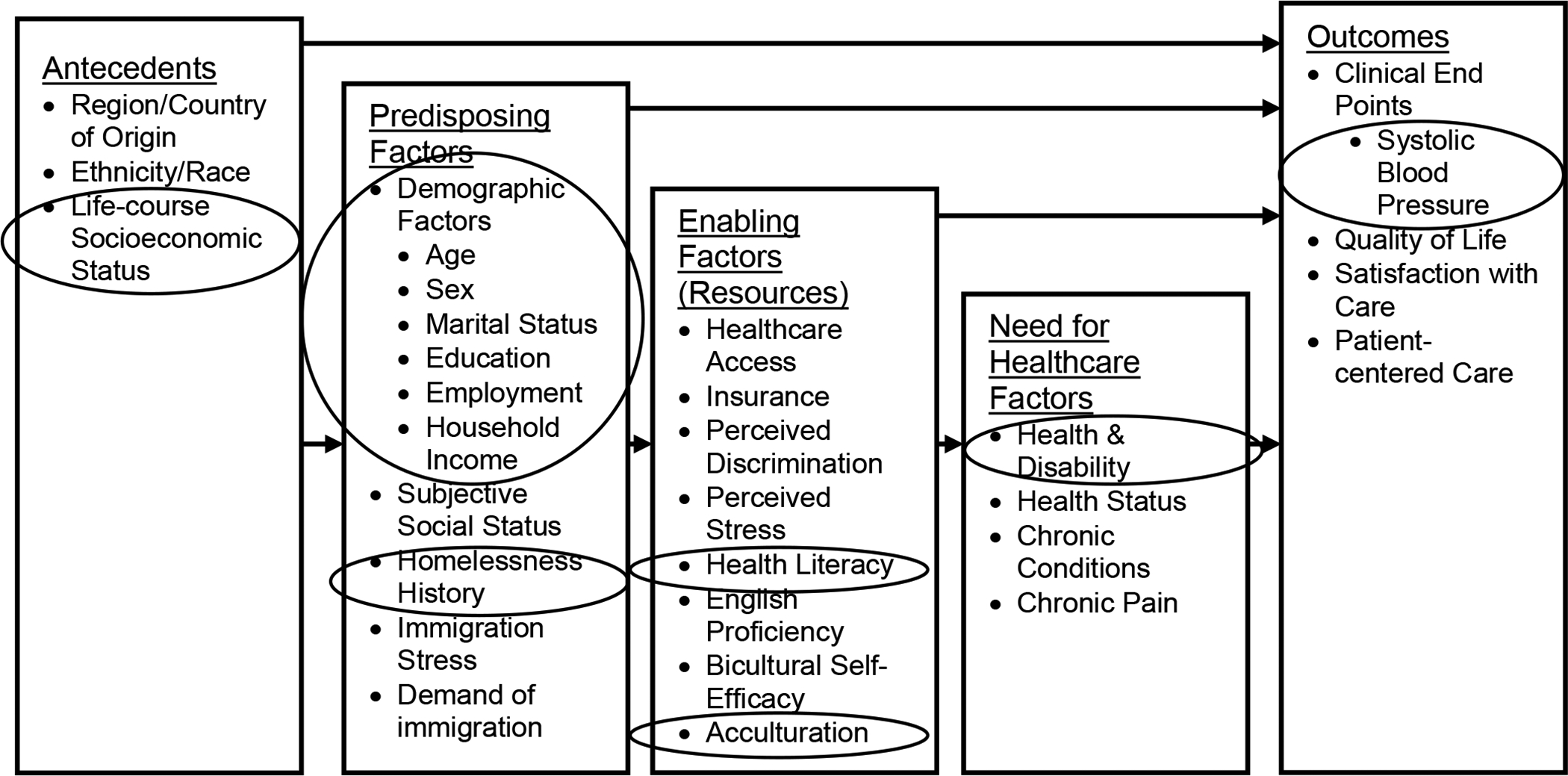

Previous research has established the relationship between antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors as predictors of health services use and clinical outcomes [20–22]. However, there is currently no validated conceptual model that explains the relationship between social determinants of health using a model that includes antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors and blood pressure control, especially in immigrant populations. To address this gap in knowledge, we developed a theory-based conceptual framework by combining the concept of antecedents proposed by Coyle & Battles [21] with the predisposing, enabling, and need factors proposed by Andersen [20]. We then incorporated immigrant-specific factors identified by Yang and Hwang [22], as well as other factors noted in the literature to develop a model that can be tested to explain the relationship between social determinants and blood pressure control among immigrants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theory-based conceptual model for immigrant social determinants of health outcomes (with indicator variables in circles)

In order to develop tailored interventions that target social determinants of health, the pathways by which social determinants influence blood pressure in immigrants needs to be understood. Therefore, we aimed to validate a new theory-based model and identify pathways between antecedent, predisposing, enabling, and need social determinants of health and systolic blood pressure among immigrants in the US. We hypothesized based on the model that antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors will have direct and indirect associations with systolic blood pressure.

Methods

Study Population

The data used for this analysis was from a cross-sectional study of a diverse group of adult US immigrants residing in the Greater Milwaukee Area of Wisconsin. Study participants were from countries in Asia, North America (Canada and Mexico), Central America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures and the study protocol prior to initiating study recruitment and enrollment. The study team consisted of two bilingual English/Spanish individuals, and all members of the study team were trained in survey research. Immigrants were defined as adults who were born in a country other than the US or its territories and were included in the study if they voluntarily agreed to participate and were aged 21 or older. Individuals were excluded if they exhibited signs of intoxication, dementia, or acute psychoses. Study participants were primarily recruited using snowball and community-based recruitment methods. Flyers with a description of the research study were also distributed in community-based settings such as international grocery stores, public libraries, restaurants and cafes, and beauty salons and barbershops. Individuals who expressed interest in participating in the study by calling the study line or requesting more information were asked to share information and flyers with other community members who may have been eligible. Additionally, mailing lists were created using the electronic health record for patients seen in General Internal Medicine clinics in the past 12 months. An informational letter and study flyer were mailed to the individuals, and those who were interested called into the study line to speak to a research team member about the study and to determine if they met eligibility criteria. Participants were completed a questionnaire in English or Spanish that was made up of validated measures of social determinants of health. The study team read the questionnaire aloud in a private setting for individuals who had difficulty seeing, reading, or writing. The validated measures assessed social determinants of health in terms of antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors.

Conceptual Model

To account for our relatively small sample size, we used selected indicator variables from our newly developed theory-based conceptual model (shown in circles in Figure 1) to indicate measures of antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors. These indicator variables were chosen because they had independent associations with SBP. Details of the variables and how they were measured are provided below.

Variables

Dependent:

Blood pressure, specifically, systolic blood pressure (SBP) was the main outcome for the study. Participants were asked to be seated for about 5 minutes upon arrival to the study visit and blood pressure was collected using an automated blood pressure monitor, the OMRON BP742N. Members of the research study team were trained by clinicians prior to study initiation and regularly throughout the course of the study on how to accurately measure blood pressure using the automated OMRON BP742N blood pressure machine. Home blood pressure monitoring guidelines for obtaining blood pressure were followed. This method is considered to be well-tolerated and has been found to have a stronger association with CVD risk compared to office BP measurement [23]. This method was appropriate for the research study since the majority of study visits occurred in community-based settings. All clinical guidelines for obtaining blood pressure measurement were followed [24], and the reading was documented in the participants chart immediately after being measured.

Antecedent:

Life-course Socioeconomic Status (Life-course SES):

Life-course SES, a measure of SES across multiple life stages, sometimes divided into early and later life, was calculated using paternal level of education, maternal level of education, the individual’s level of education, order of birth, family size, employment, and income [25, 26]. Factors serving as measures for early life SES include one’s family size, order of birth, individual educational attainment, and parental level of education [25, 26]. Whereas later life SES measures include may include employment and/or type of occupation [25]. A score was created ranging from 0 −7 where higher numbers indicated a lower- SES. The score was developed by assigning one point for each of the following items: being unemployed, having less than a high school education based on the individual and their parents’ education levels, earning less than $25,000 annually, being born last, and having more than three siblings. There were no missing data for parental level of education in the sample, and $25,000 was the approximate median income for the sample and thus was selected as the income cut point.

Predisposing Factors:

Demographic Factors:

Demographic factors including age (continuous), sex (male vs female), and marital status were assessed using previously validated items from the National Health Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [27].

Homelessness:

The 1990 Course of Homelessness Study that was conducted by the Rand Corporation was used to measure history of homelessness without a parent as a child [28].

Enabling Factors

Health Literacy:

The three-item Chew scale was used to assess health literacy [29]. This particular scale was designed to assess one’s ability to understand basic health-related information [29]. The score is calculated by summing the 3 items, where higher scores represent lower health literacy. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC] for determining inadequate health literacy with the Chew ranges from 0.66 to 0.74, and has a specificity of 83% based on the AUROC [29].

Acculturation:

The acculturation scale developed by Marin et al was used to measure acculturation across three domains: social relationships, media, and language [30]; and has an alpha of 0.92 [30]. A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess level of acculturation across the 3 domains, and was then summed to calculate an acculturation score, where higher values indicated a higher level of acculturation.

Need Factors

Disability:

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System or BRFSS has 8 previously validated questions that were used to assess current health issues [27]. Examples of the types of questions asked include having difficulty with activities like climbing stairs, having a need for special equipment such as a cane or wheelchair, and other health limitations [27]. The number of reported conditions was summed, with higher values indicating greater disability.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 14. Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the sample and to assess normality. The newly developed conceptual model was used to build the path analysis model including antecedent (life-course SES), predisposing (age, sex, married, homeless as a child alone), enabling (health literacy, acculturation), and need factors (disability) as independent predictors of systolic blood pressure. Both direct and indirect pathways were hypothesized and therefore included in the model for each of these categories. Path analysis was used due to the ability to analyze complex models and because it is a multivariate analysis methodology that allows for the testing of multiple dependent and independent relationships simultaneously [31]. In path analysis, all potential hypothesized relationships are included based on a conceptual model, with significant relationships defined as path coefficients with p<0.05. In addition, the fit of the model overall is investigated and maximized to ensure the data supports the hypothesized overarching framework [31, 32]. The maximum likelihood estimation procedure was used with standardized estimates, and was interpreted as the change in standard deviation of the outcome due to one standard deviation increase in the predictor. Standardized estimates are recommended due to the variability of the scales used to capture the measures of interest and are useful when comparing the impact of variables on the outcome [33, 34]. The direct and indirect pathways were assessed by reviewing the direction and magnitude of path coefficients. Model fit was assessed using chi2 statistic, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI). Good model fit is indicated by non-insignificant chi2 value and CFI 0.95 or greater [32, 35–37]. RMSEA of 0.05 – 0.07 indicates reasonable fit, and a value of 0.05 or less indicates good fit [32, 35–37].

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample of 181 adult immigrants in the US are shown in Table 1. Among the participants, there was an average of 14 years of education completed, average age of 45 years, with the majority being female, having a household income ≥ $25,000, and having insurance. The largest proportion of participants were born in Asia (39.8%), followed by Central America/Mexico (33.7%), Europe/Canada (14.4%), and the Middle East/Africa (12.1%). There were 29.8% with hypertension.

Table 1.

Sample demographics

| n = 181 | Percent or Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean Age | 45.4 (16.6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 66.3% |

| Years of School | |

| Mean Years of School | 14.3 (5.5) |

| Employed | |

| Mean # of Hours Worked | 24.9 (20.2) |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic or Latino | |

| Yes | 32% |

| Race | |

| White | 32.6% |

| Black | 11.6% |

| Asian | 35.9% |

| Other | 21.6% |

| Region of Birth | |

| Europe/Canada | 14.4% |

| Central America/Mexico | 33.7% |

| Asia | 39.8% |

| Middle East/Africa | 12.1% |

| Household Income | |

| < $25,000 | 42.5% |

| Insured | |

| Yes | 76.8% |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 29.8% |

Validation of the conceptual framework

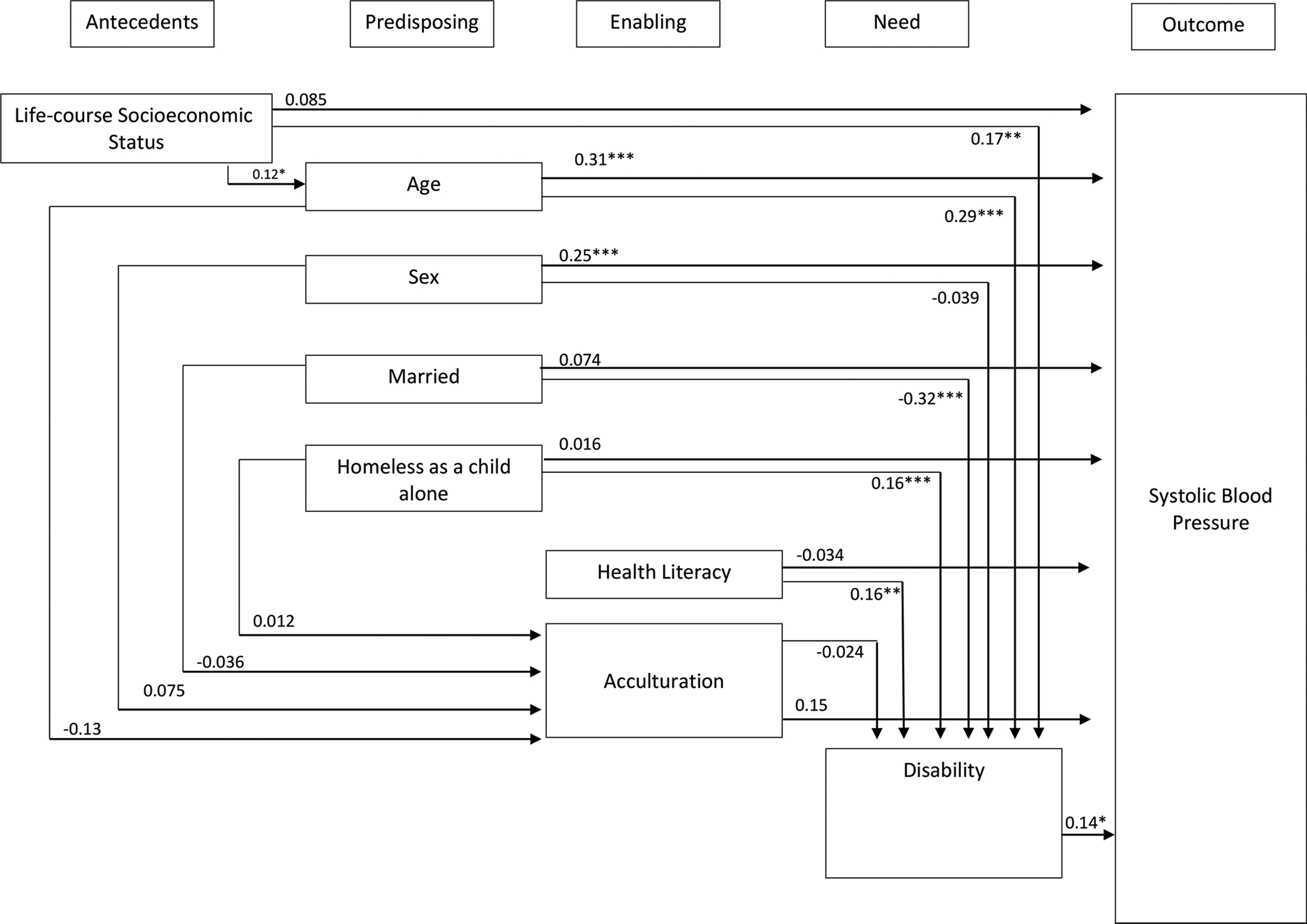

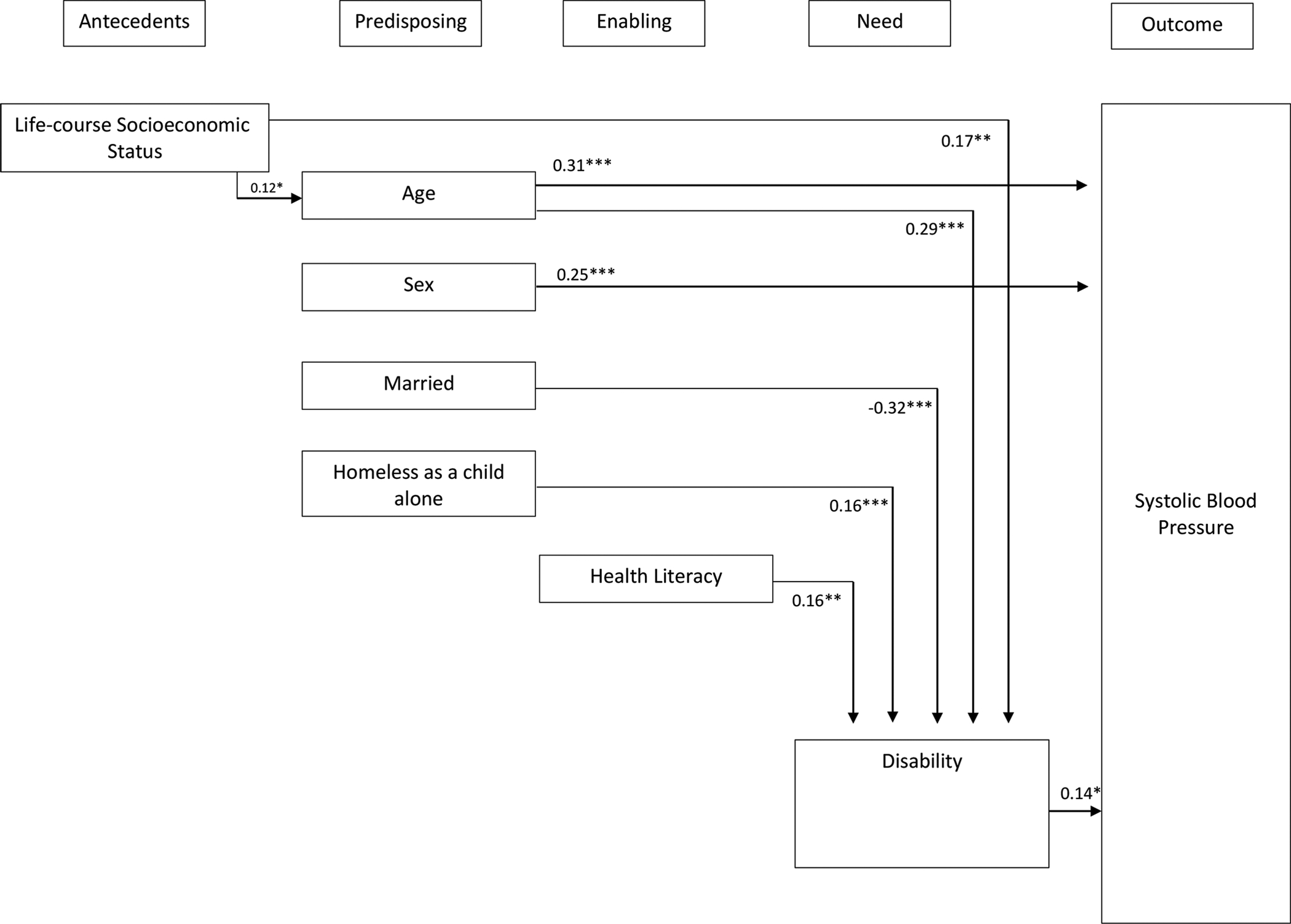

The full final model (chi2 (5) = 14.88, p=0.011, RMSEA = 0.070, pclose = 0.17, CFI = 0.96) demonstrated good fit and is shown in Figure 2. All non-significant paths were removed for the trimmed model shown in Figure 3. All r values are standardized estimates and should be interpreted in relation to the standard deviation. The final model showed the antecedent (life-course socioeconomic status (SES)) was directly associated with predisposing factor of age (0.12, p=0.019) and need factor of disability (0.17, p=0.001); and indirectly associated with disability (0.29, p<0.001) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (0.31, p<0.001). Meaning, an increase in life-course SES score, which is indicative of lower SES, was associated with an increase in age and an increase in disability. Whereas the indirect path indicates increase in life-course SES score is associated with an increase in disability that may be a result of an increase in age; and an increase in life-course SES score is associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure that may be a result of an increase in age. Predisposing factors of age (0.31, p<0.001) and sex (0.25, p<0.001) were directly associated with SBP, and age was directly associated with disability (0.29, p<0.001) and indirectly associated with SBP (0.14, p=0.018). Meaning, an increase in age was associated with an increase in SBP. Additionally, an increase in age was associated with an increase in disability, and an increase in SBP by way of disability. The other predisposing factors being married (−0.32, p<0.001) and homeless as a child alone (0.16, p<0.001) were directly associated with disability and indirectly associated with SBP (0.14, p=0.018). Therefore, being married was associated with lower disability, and being homeless as a child alone was associated with an increase in disability. Additionally, being married was associated with lower SBP by way of lower disability; and being homeless as a child was associated with an increase in SBP by way of increased disability. Enabling factor of health literacy (0.16, p=0.001) was directly associated with disability and indirectly associated with SBP (0.14, p=0.018). Therefore, an increase in health literacy score (lower health literacy) was associated with an increase in disability and an increase in SBP by way of disability. Need factor of disability (0.14, p=0.018) was directly associated with SBP.

Figure 2.

Final model. Overall model fit chi2 (5, n=181) = 14.88, p=0.011, RMSEA = 0.070, pclose = 0.17, CFI = 0.96. For paths *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Figure 3.

Trimmed final model. Overall model fit chi2 (5, n=181) = 14.88, p=0.011, RMSEA = 0.070, pclose = 0.17, CFI = 0.96. For paths *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Table 2 shows there were significant total effects of social determinants of health on SBP, including age (r=0.34, p<0.001), sex (r=0.25, p<0.001), and disability (r=0.14, p=0.02). There were also significant total effects between disability and social determinants, including life-course SES (r=0.21, p<0.001), age (r=0.30, p<0.001), being married (−0.32, p<0.001), being homeless as a child alone (r=0.16, p<0.001), and health literacy (r=0.16, p=0.001). The total effects represent the sum of the coefficients for both the direct and indirect effects of independent variables on the dependent variable in question.

Table 2.

Direct, Indirect and Total Effects of Antecedent, Predisposing, Enabling and Need Variables on Systolic Blood Pressure

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic Blood Pressure | |||

| Antecedent | |||

| → Life-course Socioeconomic Status (SES) |

0.085 | 0.017 | 0.10a |

| Predisposing | |||

| → Age | 0.31*** | 0.022 | 0.34*** |

| → Sex | 0.25*** | 0.0053 | 0.25*** |

| → Married | 0.074 | −0.49* | 0.024 |

| → Homeless as a Child Alone | 0.16 | 0.024 | 0.040 |

| Enabling | |||

| → Health Literacy | −0.34 | 0.021a | −0.12 |

| → Acculturation | 0.15 | −0.0033 | 0.14 |

| Need | |||

| → Disability | 0.14* | -- | 0.14* |

| Disability | |||

| Antecedent | |||

| → Life-course Socioeconomic Status (SES) |

0.17** | 0.043 | 0.21*** |

| Predisposing | |||

| → Age | 0.29*** | 0.0031 | 0.30*** |

| → Sex | −0.039 | −0.0018 | −0.041 |

| → Married | −0.32*** | 0.00085 | −0.32*** |

| → Homeless as a Child Alone | 0.16*** | −0.00028 | 0.16*** |

| Enabling | |||

| → Health Literacy | 0.16** | -- | 0.16** |

| → Acculturation | −0.024 | -- | −0.024 |

| Acculturation | |||

| Antecedent | |||

| → Life-course Socioeconomic Status (SES) |

−0.32*** | −0.015 | −0.34*** |

| Predisposing | |||

| → Age | −0.13 | -- | −0.13 |

| → Sex | 0.075 | -- | 0.075 |

| → Marital Status | −0.036 | -- | −0.036 |

| → Homeless as a Child Alone | 0.012 | -- | 0.012 |

| Age | |||

| Antecedent | |||

| → Life-course Socioeconomic Status (SES) |

0.12* | -- | 0.12* |

p=0.05,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Discussion

Among this convenience sample of diverse immigrants residing in the Greater Milwaukee Area of Wisconsin, we found predisposing (age, sex) and need (disability) factors to have a direct pathway to systolic blood pressure. In addition, we found antecedent (life-course SES), predisposing (age, married, homeless as a child alone), and enabling (health literacy), factors to have an indirect pathway to systolic blood pressure as hypothesized in the conceptual model. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no significant pathway from predisposing to enabling factors (such as acculturation). The identified direct and indirect relationships suggest that lower SES is associated with increased disability; and increasing age is associated with increased disability and increased SBP. Male sex was found to be directly associated with increased SBP, while being married was found to be associated with decreased disability and indirectly with decreased SBP. Being homeless as a child alone was directly associated with increased disability and indirectly associated with increased SBP, and having low health literacy was found to be directly associated with increased disability and indirectly associated with increased SBP.

This study is one of the first to test and validate a theory-based conceptual framework that explains the relationship between social determinants of health grouped by antecedents, predisposing, enabling, need, and systolic blood pressure among US adult immigrants. The model was created based on identification of existing health services research models and the addition of immigrant specific factors allowing for the conceptualization and analysis of the relationships between social determinants of health and outcomes. We were also able to successfully elucidate both direct and indirect pathways, providing additional explanatory power of these relationships. By understanding the mechanism by which social determinants of health affects SBP we are able to identify potential pathways that can be focal points for interventions to control blood pressure in immigrant populations. Based on these findings, history of low life-course SES, homelessness when under the age of 18 without a parent, low health literacy, and high disability burden in immigrant adults should be red flags for clinicians and other healthcare providers and should trigger aggressive psychosocial and clinical interventions to lower blood pressure.

While factors such as acculturation are often highlighted and have previously been identified as key predictors of immigrant health [38–40], we did not find significant pathways between acculturation and either disability or systolic blood pressure in this analysis. Additionally, since SES and acculturation are two separate constructs, we do not believe SES confounded the effect of acculturation. However, it is possible that SES was a stronger driver of blood pressure in this particular sample of immigrants and that may be why we saw significant results for SES but not for acculturation. These findings highlight the strength of using robust methodologies such as SEM and path analysis that account for error terms and allows inclusion of multiple dependent and independent variables in one model. The inclusion of multiple dependent and independent variables in one model allows for accounting of overlapping influence and studying of both direct and indirect effects. By testing direct and indirect pathways we are able to find unique contribution of variables to target interventions. Interventions can be developed to target direct or indirect predictors of the outcome, increasing the number of ways diseases can be improved. For example, interventions to increase life-course SES through education, job and skills training to increase one’s earning potential; health literacy interventions; or programs to decrease or manage disabilities are all viable courses of action for improving hypertension in immigrants based on our findings. Our results illustrate the need for additional work on understanding the pathways by which social determinants of health influence hypertension and other CVD risk factors, particularly obesity, high cholesterol, and diabetes. Future research should include larger and more diverse samples of immigrants residing in various regions of the US to contribute to the body of knowledge and increase generalizability.

Our study has two main strengths: 1) utilization of path analysis, a robust methodology that allows us to understand the pathways by which social determinants of health influence blood pressure, and 2) inclusion of a diverse sample of immigrants from multiple regions of the world. The study also has two main limitations to discuss. First, the study was conducted with a relatively small sample of immigrants residing in the Midwestern US and should be conducted with immigrants residing in other regions of the US regions. Secondly, causality cannot be inferred based on the results due to the cross-sectional study design. Thirdly, only one blood pressure measurement was collected, instead of taking an average of multiple readings. This measurement technique may result in reporting of slightly higher blood pressure values.

Conclusions

To conclude, this study successfully validated a theory-based conceptual model of the relationship between immigrant specific social determinants of health categorized as antecedents, predisposing, enabling, and need factors and systolic blood pressure. Predisposing and need factors, specifically age, sex and disability, had a direct path to SBP, and antecedents, predisposing, and enabling factors, specifically life-course SES, married, homelessness as a child alone, and health literacy had an indirect path to SBP. Based on these findings, history of low life-course SES, homelessness as a child without a parent, low health literacy, and high disability burden in immigrant adults should be red flags for clinicians and other healthcare providers and should trigger aggressive psychosocial and clinical interventions to lower blood pressure.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, … Ezzati M. (2012). A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990 – 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 380, 2224 – 2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, … Turner MB. (2015). Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 131, e29 – e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khavjou O, Phelps D, Leib A. (2016). Projections of cardiovascular disease prevalence and costs: 2015 – 2035. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Census Bureau. (2018). Quick facts: United States. 2018; Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217#PST045217

- 5.Brown AGM, Houser RF, Mattei J, Mozaffarian D, Lichtenstein AH, Folta SC. (2017). Hypertension among U.S.-born and foreign-born non-Hispanic Blacks: NHANES 2003 – 2014 data. Journal of Hypertension, 35, 2380 – 2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commodore-Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Obisesan O, Aboagye JK, Agyemang C, Reilly CM, Dunbar SB, Okosun IS. (2016). Length of residence in the United States is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in immigrants: a contemporary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of the American Heart Association, 5, e004059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commodore-Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Cooper LA, Agyemang C, Himmelfarb CD. (2018). The association between acculturation and cardiovascular disease risk in Ghanaian and Nigerian-born African immigrants in the United States: the Afro-Cardiac Study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20, 1137 – 1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyamfi J, Butler M, Williams SK, Agyemang C, Gyamfi L, Seixas A, Zinsou GM, Bangalore S, Shah NR, Ogedegbe G. (2017). Blood pressure control and mortality in US- and foreign-born blacks in New York City. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 19, 956 – 964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Wong EC, Berthold SM, Hambarsoomian K, Elliott MN, Bardenheier BH, Gregg EW. (2016). Diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk in Cambodian refugees. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18, 110 – 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas JJ, Abdelbary B, Rentfro A, Fisher-Hoch S, McCormick JB. (2014). Cardiovascular disease risk among the Mexican American population in the Texas-Mexico border region, by age and length of residence in United States. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, 130253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poston WSC, Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ, Ogbonnaya K, Hanis CL, Haddock CK … Foreyt JP. (2001). Genetic bottlenecks, perceived racism, and hypertension risk among African Americans and first-generation African immigrants. Journal of Human Hypertension, 15, 341 – 351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commodore-Mensah Y, Turkson-Ocran R-A, Foti K, Cooper LA, Himmelfarb CD. (2021). Associations between social determinants and hypertension, stage 2 hypertension and controlled blood pressure among men and women in the US. American Journal of Hypertension, 10.1093/ajh/hpab011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. (2017). Social determinants of health: about social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Social determinants of health: know what affects health. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. (2017). The social determinants of chronic disease. American Journal of Prevention Medicine, 52(1 Suppl 1): S5 – S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bidulescu A, Francis DK, Ferguson TS, Bennett NR, Hennis AJM, Wilks R, … Sullivan LW. (2015). Disparities in hypertension among black Caribbean populations: a scoping review by the U.S. Caribbean Alliance for Health Disparities Research Group (USCAHDR). International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zallman L, Himmelstein D, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, Ayanian JZ, Wilper AP, McCormick D. (2013). Undiagnosed and uncontrolled hypertension and hyperlipidemia among immigrants in the US. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15, 858 – 865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall E, Cuellar NG. (2016). Immigrant health in the United States: a trajectory toward change. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27, 611 – 626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luque JS, Soulen G, Davila CB, Cartmell K. (2018). Access to health care for uninsured Latina immigrants in South Carolina. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen RM. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 1 – 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyle YM, Battles JB. (1999). Using antecedents of medical care to develop valid quality of care measures. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 11, 5 −12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang PQ, Hwang SH. (2016). Explaining immigrants health service utilization: a theoretical framework. Sage Open, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, … Wright JT. (2019). Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 73(5): e35–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Heart Association. (2018). Monitoring your blood pressure at home. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association. Retrieved from: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings/monitoring-your-blood-pressure-at-home [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wamala SP, Lynch J, Kaplan GA. (2001). Women’s exposure to early and later life socioeconomic disadvantage and coronary heart disease risk: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merkin SS, Karlamangla A, Roux AVD, Shrager S, Seeman TE. (2014). Life course socioeconomic status and longitudinal accumulation of allostatic load in adulthood: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American Journal of Public Health, 104: e48 – e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 28.RAND Health. (2018). Homelessness survey from RAND Health. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/homelessness.html [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, … Vanryn M. (2008). Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23, 561 – 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin B, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. (1987). Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 183 – 205. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. (2010). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling: Third Edition. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kline RB. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwan JLY, Chan W. (2011). Comparing standardized coefficients in structural equation modeling: a model reparameterization approach. Behavioral Research, 43, 730 – 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez BN, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Ryan LM, Hu H. (2005). Structural equation models: a review with applications to environmental epidemiology. Journal of American Statistics Association, 100, 1443 – 1455. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cangur S, Ercan I. (2015). Comparison of model fit indices used in structural equation modeling under multivariate normality. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 14, 152 – 167. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu L; Bentler PM. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1 – 55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53 – 60. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran A, Roux AVD, Jackson SA, Kramer H, Manolio TA, Shrager S, Shea S. (2007). Acculturation is associated with hypertension in a multiethnic sample. American Journal of Hypertension, 20, 354 – 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffen PR, Smith TB, Larson M, Butler L. (2006). Acculturation to Western society as a risk factor for high blood pressure: a meta-analytic review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 386 – 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teppala S, Shankar A, Ducatman A. (2010). The association between acculturation and hypertension in a multiethnic sample of US adults. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension, 4, 236 – 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]