Abstract

Though survival in bilateral retinoblastoma (RB) has improved due to advancement in diagnostics and treatment modalities, children require long-term follow-ups for recurrence and second malignancies. We report a case of bilateral RB in a 7-month-old baby who was treated with chemotherapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, and periocular carboplatin for both eyes following which there was complete regression of tumour. Six and a half years after treatment, the child presented with metastatic recurrence of tumour in the left ulna. He was treated successfully with chemotherapy, extracorporeal radiation and reimplantation therapy. A less aggressive treatment approach for isolated bone relapse may be considered in selected cases.

Keywords: Retinoblastoma, Late metastasis, Relapse, ECRT

Established Facts

Already known fact 1: children with retinoblastoma require long-term follow-ups for second malignancies and relapse.

Already known fact 2: relapses usually occur locally and mostly within the first 2 years of treatment.

Novel Insights

New information 1: we report a case of a 7-month-old baby treated for bilateral retinoblastoma who presented 6 ½ years after therapy with isolated bone relapse.

New information 2: second-line chemotherapy and extracorporeal radiation therapy may be suitable alternatives to more aggressive forms of treatment, especially in limited bone relapse.

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common intraocular malignant neoplasm in children, accounting for 4% of all paediatric malignancies [1, 2, 3]. RB arises from the embryonic neural retina [3]. In 60% of cases, RB is unilateral and of the non-hereditable variety occurring in isolation with no previous family history. In 40% of cases, it occurs due to a germ line mutation in the RB1 gene and is hereditable and usually bilateral [4]. Bilateral RB has been reported in 25–35% of cases, and those with hereditary RB1 mutations have an increased risk of subsequent cancers such as osteosarcoma and malignant melanoma [5, 6].

Survival in RB has improved to more than 90% due to advancement in diagnostics and treatment modalities [7, 8]. However, these children require close follow-ups for long-term complications, second malignancies, and relapse. Relapses are usually local and occur mostly within the first 2 years of treatment [9, 10]. There have been few reports of late metastatic relapse of RB [1, 11, 12]. We report a case of a 7-month-old male baby treated for bilateral RB who presented with very late relapse 6 ½ years after therapy, involving the left ulna, now treated successfully with second-line chemotherapy and extracorporeal radiation therapy.

Case Report

A 7-month-old baby boy, born at term, and the only child of a non-consanguineous couple was detected to have white reflex in his left eye during routine paediatric check-up. There was no history of family members affected with RB or other visual problems. Fundoscopic examination, CT brain, and orbit, and correlative ultrasound of both globes were done, which showed soft tissue density opacity lesions in the posterior compartment of both globes (left > right) with coarse calcifications within, suggestive of bilateral multifocal RB. The CT scan showed both globes were normal in size. The right globe measured 20.7 × 20.5 mm. The left globe measured 19.9 × 19.7 mm. A soft tissue density opacity measuring 18.7 × 17.4 mm was observed in the posterior compartment of the left globe with coarse calcifications noted in the lesion. The right globe showed a small soft tissue density opacity lesion in the posterior compartment with coarse calcification. Correlative ultrasound revealed an isodense lesion in the posterior compartment of the left globe. Bilateral optic nerve sheath complexes were normal. Bone marrow and CSF studies were normal. Vision was preserved in both eyes. Grading of initial tumour showed that tumour affecting the right eye was group A with AJCC classification c T1a N0 M0, and the left eye was group E tumour with neovasular glaucoma and AJCC classification c T3c N0M0. There were no vitreous seeds.

The child was initially treated with 6 cycles of VEC chemotherapy every 3 weeks (vincristine 0.05 mg/kg, etoposide 5 mg/kg × 3 days, and carboplatin 18 mg/kg), with regular ophthalmology evaluation between the chemo-cycles. As the response after 6 cycles of VEC was suboptimal, he was subsequently treated at another centre with transpupillary thermotherapy and periocular carboplatin for both eyes, following which there was complete regression of tumour. He had been on regular post-treatment follow-up, which showed complete regression of tumour in both the eyes with vision in the right eye of 6/6 and the left eye of 6/60.

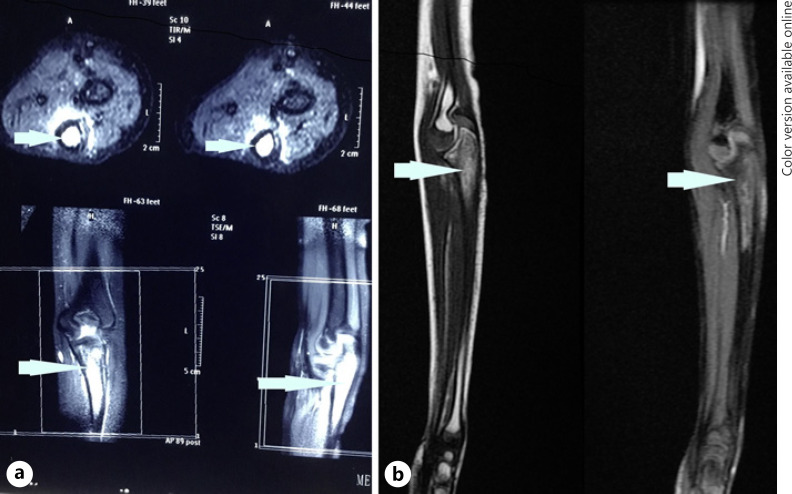

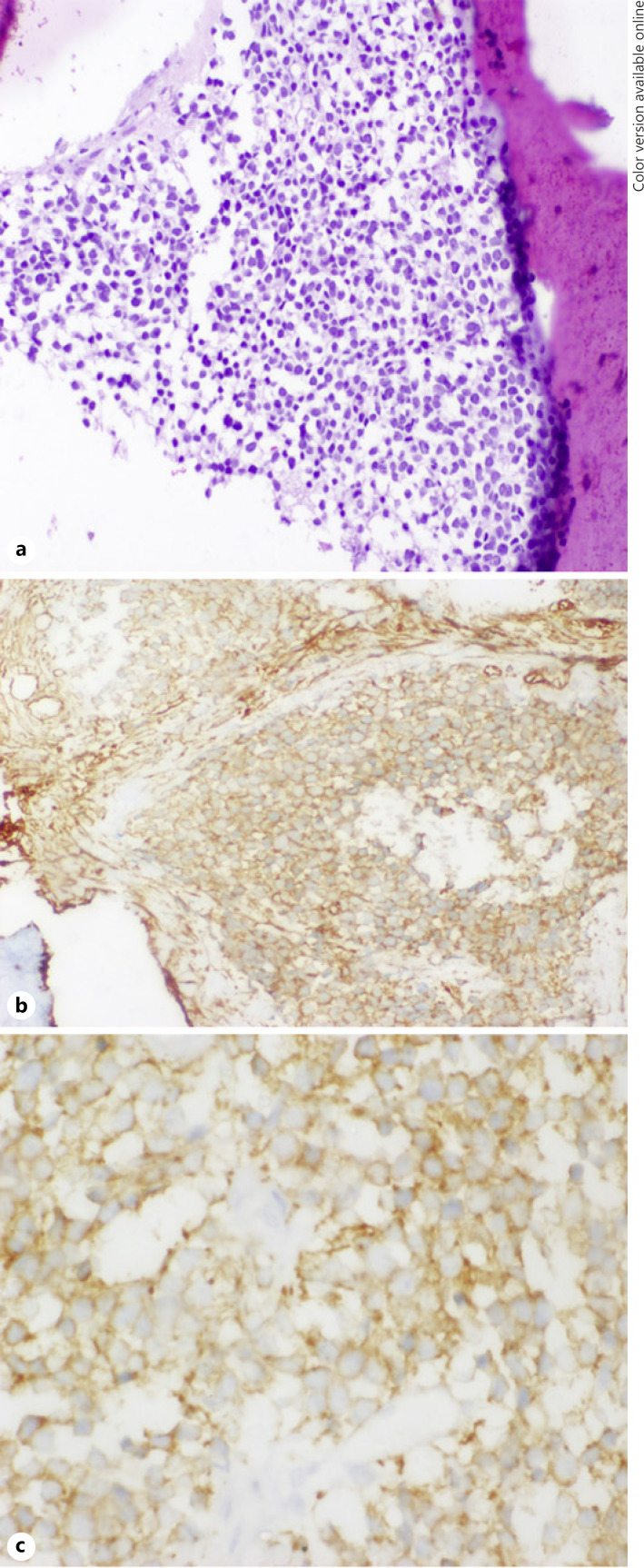

Six and a half years after treatment, the child presented with pain in his left proximal forearm. On examination, there was mild tenderness over the proximal ulnar bone, with no obvious swelling or redness. Radiograph showed lytic sclerotic lesion involving proximal meta-diaphysis of the left ulna with wide zone of transition, solid periosteal reaction, and cortical irregularities (shown in Fig. 1). MRI further confirmed the lesion limited to proximal meta-diaphysis of the left ulna seen as abnormal STIR hyperintensity involving the marrow with cortical erosion and associated soft tissue component (shown in Fig. 2). The bone scan showed uptake only at the left upper forearm. Bone marrow and CSF analysis did not show any evidence of disease. The CT thorax did not show any pulmonary metastasis. Bone biopsy was done, and histopathology showed infiltration of the intertrabecular space by sheets of small round cells having scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei. The differentials considered were small cell osteosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and metastatic small round cell neoplasm. Radiology was not suggestive of osteogenic sarcoma; hence, small-cell osteosarcoma was ruled out. Immunohistochemistry showed tumour cells to be chromogranin cytoplasmic granular positive, synaptophysin diffuse strong positive, CD56 diffuse strong positive, MIC2 cytoplasmic and membrane positive, desmin and myogenin negative (shown in Fig. 3). The tumour cells were positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD 56, which denotes neuroendocrine/neuroectodermal differentiation. Retinal markers were not done due to non-availability. Ewing's sarcoma translocations done were negative for EWS-FLI1 type 1 and type 2 and EWS-ERG, which together account for 95% of translocations associated with Ewing's sarcoma. Tumour cells in Ewing's sarcoma can be CD56 and synaptophysin positive, but chromogranin negative. Positivity for chromogranin, absence of typical crisp membrane pattern of staining for CD99, and negative translocation ruled out Ewing's sarcoma. Hence, we considered metastatic small round-cell neoplasm in this case. Based on the immunoprofile which showed positive staining for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56, negative RT-PCR for translocations of Ewing's sarcoma, and a positive history of bilateral RB, the possibility of metastatic RB was highly favoured [13].

Fig. 1.

a Pre-chemo X-ray of the left elbow showing mixed lytic sclerotic lesion in the proximal ulna, wide zone of transition involving proximal meta-diaphysis with cortical thickening and irregularity. b Post-chemo showing no evidence of tumour.

Fig. 2.

aPre-chemo T2W/STIR MRI: hyperintense marrow signal in proximal meta-diaphysis, cortical erosion, and minimal soft tissue component. b Post-chemo: residual marrow signal, hypointense in T1W/T2W, mild cortical thickening, and regression of soft tissue component.

Fig. 3.

HE stain ×100: sheets of small round cells with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (a); MIC2 ×400 showing cytoplasm and membrane positivity (b); synaptophysin ×400 showing diffuse strong membrane positivity (c).

The child was started on chemotherapy with vincristine 2 mg/m2 × 1 day, doxorubicin 30 mg/m2 × 1 day, cyclophosphamide 600 gm/m2 × 2 days alternating with cisplatin 100 mg/m2 × 1 day, and etoposide 100 mg/m2 × 5 days every 3 weeks. The child tolerated chemotherapy well with no major complications. After 7 cycles of chemotherapy, the child was re-evaluated. Both eyes showed no active tumour. Repeat X-ray was normal (Fig. 1), and MRI of the left forearm showed residual altered marrow signal intensity involving the proximal meta-diaphyseal region of the left ulna. There was near total regression of the extra-osseous soft tissue when compared to the previous scan (shown in Fig. 2). The child then underwent limb salvage surgery with wide local excision of the ulna at the metastatic site, followed by extracorporeal radiation and reimplantation therapy (ECRT). The bone segment bearing the tumour was resected, the tumour shaved off the bone, and the periosteum stripped. The resected bone segment was covered in an antibiotic soaked gauze, sealed in a sterile plastic, and transported to the radiation unit in a sterile manner where a single fraction of 50 Gy of radiation therapy was given extracorporeally using a 4 MV Elekta Synergy® S linear accelerator. The whole process takes a short time, while the patient continues to be under anaesthesia. The irradiated bone segment was then reimplanted as an auto graft and fixed to the remaining ulna with a 15-hole recon plate. The elbow capsule, the medial and the lateral ligaments were then reattached. Triceps tendon was also reattached. The post-operative period was uneventful. The histopathology of bone scrapings sent from the surgical margins did not show any viable tumour. After the surgery, the child received one more course of chemotherapy with vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide. The patient is now 1 year 11 months from the diagnosis of the ulnar lesion and remains recurrence-free. Repeat X-ray showed completely reunited bone. The child has a good range of movements and normal elbow function.

Discussion

Survival of children with RB is >90% in the developed countries. In low- and middle-income countries, survival is estimated to be 50–60% and has been attributed to late referrals mostly after the extraocular spread has already occurred [4, 14, 15]. Recurrences in RB usually occur within 2 years of treatment completion [9, 10]. Late isolated metastatic recurrence is extremely rare with a handful of isolated case reports [1, 11, 12, 16]. The prognosis of children with extraocular metastatic RB is poor, and treatment continues to be a challenge. The current guidelines propose an intensive chemotherapy treatment plus high-dose chemotherapy, followed by peripheral blood stem cell rescue and radiotherapy for bulky metastasis [17, 18]. However, high-dose chemotherapy followed by peripheral blood stem cell rescue was not an option for this child. Due to financial and resource constraints, the oligometastatic nature of the disease, accessible location of tumour, and excellent response to induction chemotherapy, we went ahead with metastatectomy, followed by ECRT. Metastatectomy is recommended for all solid tumours where it is oligometastatic and feasible, to improve survival. We could have used a prosthetic implant; however, ECRT is more economical and is a more standard practice of care for primary bone tumours in our institute.

The child responded well to 2nd-line chemotherapy, followed by ECRT of the affected bone. ECRT as a limb salvage procedure is used in many centres for the treatment of primary bone tumours and has shown favourable results. The single high dose makes the bone segment non-viable with no possibility of tumour recurrence. There is also no risk of irradiating adjacent structures as the radiation is delivered only to the bone segment extracorporeally. ECRT was considered a better option in this child as direct RT to the site would expose surrounding tissues to effects of RT and predispose to second malignancies, this child being already at risk due to possible genetic mutation in those with bilateral RB.

A second neoplasm in the form of bone and soft tissue malignancies are not uncommon in children with hereditary RB, and these children need to be carefully screened for them [3]. In our child, Ewing's sarcoma was considered as a possible diagnosis; but because of a negative RT-PCR for translocations of Ewing's sarcoma, a metastatic RB was favoured.

In conclusion, patients who are treated for bilateral RB need to be under continuous follow-up to detect second malignancies and late relapses. Isolated metastatic recurrence, though rare, is still a possibility. Even though high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous transplant has been recommended as the treatment of choice for metastatic recurrence, considering the late recurrence and regressed tumour in the eyes, a possible less aggressive treatment option may be considered, especially if the metastasis is not extensive.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the parent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

There is no financial funding to declare.

Author Contributions

Deepthi Boddu: conception of work, design, acquisition of data, analysis of data, drafting the work, critical revision, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Priyakumari Thankamony: conception of work, design, acquisition of data, drafting the work, critical revision, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Reshma Prakasam: conception of work, acquisition of data, critical revision, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Subin Sugath: conception of work, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting the work, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Aswin Kumar: acquisition and analysis of data, drafting the work, final approval of the version published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Sindhu Nair: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work; final approval of the version published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Choi JY, Kang HJ, Lee JW, Ju HY, Hong CR, Kim H, et al. Very late relapse of bilateral retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015 May;37((4)):e264–7. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Shields JA. Diagnosis and management of retinoblastoma. Cancer Control. 2004 Oct;11((5)):317–27. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seth R, Singh A, Guru V, Chawla B, Pathy S, Sapra S. Long-term follow-up of retinoblastoma survivors: Experience from India. South Asian J Cancer. 2017 Oct-Dec;6((4)):176–9. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_179_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakhshi S, Bakhshi R. Genetics and management of retinoblastoma. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2007 Jul 1;12((3)):109. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blank JE, Dormans JP, Himelstein BP, Yamashiro D. Metastatic retinoblastoma. Recent progress of interest to orthopaedic surgeons. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995 Jun;((315)):251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chintagumpala M, Chevez-Barrios P, Paysse EA. Plon SE, Hurwitz R. Retinoblastoma: review of current management. Oncologist. p. 123746. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Friedman DN, Chou JF, Oeffinger KC, Kleinerman RA, Ford JS, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic medical conditions in adult survivors of retinoblastoma: results of the retinoblastoma survivor study. Cancer. 2016 Mar 1;122((5)):773–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis JH, Levin AM, Zabor EC, Gobin YP, Abramson DH. Ten-year experience with ophthalmic artery chemosurgery: ocular and recurrence-free survival. PLoS ONE. 2018;13((5)):e0197081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JW, Kathpalia V, Dunkel IJ, Wong RK, Riedel E, Abramson DH. Orbital recurrence of retinoblastoma following enucleation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009 Apr;93((4)):463–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.138453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Cater J, Shelil A, Meadows AT, Shields JA. Chemoreduction for retinoblastoma. Analysis of tumor control and risks for recurrence in 457 tumors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004 Sep;138((3)):329–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuruva M, Mittal BR, Kashyap R, Bhattacharya A, Marwaha RK. Bilateral retinoblastoma presenting as metastases to forearm bones four years after the initial treatment. Indian J Nucl Med. 2011 Apr;26((2)):115–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.90268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uppuluri R, Jayaraman D, Sivasankaran M, Patel S, Vellaichamy Swaminathan V, Raj R. Successful treatment of relapsed isolated extraocular retinoblastoma in the right fibula with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019 Mar 29;41:402–3. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sengupta S, Pan U, Khetan V. Adult onset retinoblastoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;64((7)):485–91. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.190099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leal-Leal C, Flores-Rojo M, Medina-Sansón A, Cerecedo-Díaz F, Sánchez-Félix S, González-Ramella O, et al. A multicentre report from the Mexican retinoblastoma group. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 Aug;88((8)):1074–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.035642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chawla B, Hasan F, Azad R, Seth R, Upadhyay AD, Pathy S, et al. Clinical presentation and survival of retinoblastoma in Indian children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb;100((2)):172–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ting SC, Kiefer T, Ehlert K, Goericke SL, Hinze R, Ketteler P, et al. Bone metastasis of retinoblastoma five years after primary treatment. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020 Jul 17;19:100834. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Chantada GL, Haik BG, Wilson MW. Treatment of retinoblastoma: current status and future perspectives. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2007 Jul;9((4)):294–307. doi: 10.1007/s11940-007-0015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaradat I, Mubiden R, Salem A, Abdel-Rahman F, Al-Ahmad I, Almousa A. High-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation in the management of retinoblastoma: a systematic review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2012;5((2)):107–17. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2012.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]